Abstract

Assessments of cancer survivors’ health-related needs are often limited to national estimates. State-specific information is vital to inform state comprehensive cancer control efforts developed to support patients and providers. We investigated demographics, health status/quality of life, health behaviors, and health care characteristics of long-term Utah cancer survivors compared to Utahans without a history of cancer. Utah Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 2009 and 2010 data were used. Individuals diagnosed with cancer within the past 5 years were excluded. Multivariable survey weighted logistic regressions and computed predictive marginals were used to estimate age-adjusted percentages and 95 % confidence intervals (CI). A total of 11,320 eligible individuals (727 cancer survivors, 10,593 controls) were included. Respondents were primarily non-Hispanic White (95.3 % of survivors, 84.1 % of controls). Survivors were older (85 % of survivors ≥40 years of age vs. 47 % of controls). Survivors reported the majority of their cancer survivorship care was managed by primary care physicians or non-cancer specialists (93.5 %, 95 % CI = 87.9–99.1). Furthermore, 71.1 % (95 % CI = 59.2–82.9) of survivors reported that they did not receive a cancer treatment summary. In multivariable estimates, fair/poor general health was more common among survivors compared to controls (17.8 %, 95 % CI = 12.5–23.1 vs. 14.2 %, 95 % CI = 12.4–16.0). Few survivors in Utah receive follow-up care from a cancer specialist. Provider educational efforts are needed to promote knowledge of cancer survivor issues. Efforts should be made to improve continuity in follow-up care that addresses the known issues of long-term survivors that preclude optimal quality of life, resulting in a patient-centered approach to survivorship.

Keywords: Cancer survivors, Behavioral surveillance, Health status, Quality of life, Health behavior, Health care, Cancer, Public health surveillance

Introduction

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2015 more than 14.5 million cancer survivors were living in the United States (U.S.). By 2024, this number is expected to increase to almost 19 million [1]. Supporting this growing population of survivors is essential to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP), which provides support to organizations in states, tribal groups, and territories in understanding the burden of cancer, improving access to care, and enhancing quality of life for survivors. However, few state-specific assessments have identified areas of action for the NCCCP program [2–5].

State-specific assessments are important for enhancing NCCCP strategic plans at the local level. National studies demonstrate pervasive issues for cancer survivors including poorer health status compared to those without cancer [6], rural and urban health disparities [7], lower quality of life, and greater levels of activity limitations [7–10]. Other issues for survivors include a high prevalence of comorbid conditions, lower life satisfaction, and low social and emotional support [9]. At the same time, survivors have often experienced financial issues during treatment [11], which may affect their access to care. Despite these concerns, national data are limited on key components of long-term survivorship care among adult survivors, such as how often survivors receive survivorship care plans or treatment summaries. Even less is known about the status of survivorship care at the state level. However, the limited number of studies to date demonstrates concerns regarding long-term survivorship care, including that only one-third of cancer survivors receive survivorship care plans or treatment summaries [12, 13], longer-term survivors are less likely to see a cancer-focused physician [14], and that publically insured or uninsured survivors have lower access to preventive care [15]. Utah is projected to have one of the biggest population booms over the next decade, growing at twice the national average [16]. Currently, over 80,000 cancer survivors are living in Utah, which is estimated to grow with improved screening and treatments [17]. Utah has distinct features with important implications for cancer control. Utah has the lowest smoking rate [18] in the nation and the highest incidence rate of melanoma (34.6 per 100,000 compared to 19.9 per 100,000 nationally) [19, 20]. Utah’s age distribution is the youngest in the nation, with 31.5 % of residents under the age of 18 vs. 24 % in the U.S. [21].

Using the Utah 2009 and 2010 Utah Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data, our objective was to evaluate the demographic characteristics, health status, health behaviors, and health care characteristics of cancer survivors who were five or more years from diagnosis, compared to Utahans without cancer [22]. In conjunction with assessing the general health care characteristics of survivors, such as insurance coverage and health care costs, we also evaluated several items regarding cancer survivorship care that were collected in 2010, including types of providers seen and receipt of treatment summaries. As the 2016–2020 Utah State Cancer Control Plan [17] has the goal of providing education, age-appropriate services, and resources to improve quality of life for survivors, this effort is essential to identify statewide public health priorities to support Utah’s survivors.

Methods

Data

BRFSS is an important public health collaborative project of the CDC and U.S. states and territories [23]. The BRFSS survey, administered and supported by CDC's Behavioral Surveillance Branch, is an ongoing data collection program designed to measure behavioral risk factors for the adult population (18 years of age or older). BRFSS uses random-digit telephone dialing methods to sample non-institutionalized adults aged 18 years or older. The national BRFSS survey includes standardized questions addressing demographic characteristics, socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and risk factors that are organized as core questions and state-added questions. The national BRFSS survey also has added optional state modules for cancer survivors. Utah included these modules in 2009 and 2010 which is the focus of this report. BRFSS survey design, sample characteristics, and surveys are available at www.cdc.gov/brfss.

Participant Sample

To identify cancer survivors, the BRFSS survey asks, “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you had cancer?” This item was included for all Utah BRFSS respondents in 2009 and for a randomly-selected subset in 2010 (approximately one-quarter of 2010 BRFSS respondents). Cancer survivors were defined as those who answered Byes^ to this question. Anyone who answered this question was considered eligible. The test–re-test reliability for this question, as part of the BRFSS survey nationally, is excellent at k = 0.91. For all analyses, we included only those survivors who were five or more years from their first primary cancer diagnosis. The inclusion of survivors who were five or more years following their primary cancer diagnosis supported comparisons with previous studies [24] and our larger goal of understanding long-term survivors’ needs to support public health efforts. Respondents were also excluded if they had missing/unknown age or had non-melanoma skin cancers. In our sample, 727 survivors (n = 588 in 2009, n = 139 in 2010) met eligibility criteria, with 10,593 identified for the control group (n = 8,444 in 2009, n = 2,149 in 2010).

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

BRFSS respondents were asked to report their gender (male or female), current age, and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic/Latino, and other/mixed). Other demographic questions included highest educational attainment, employment status, and household income.

Characteristics of Cancer Survivors

Cancer survivors were asked follow-up questions in the added modules to determine age at diagnosis, how many cancer diagnoses they have had, and type of cancer. The number of years since diagnosis was calculated using respondents’ current age and age at first diagnosis.

Health Status/Quality of Life

All BRFSS respondents completed the CDC’s health-related quality of life measure (CDC-HRQOL-4, known as the “Healthy Days Measures”) [25]. This measure assessed health status which we categorized as fair/poor vs. excellent/very good/good, number of unhealthy physical or mental health days (within the past 30 days), and number of days when poor health restricted usual activities. Similar to other reports, we dichotomized at ≥15 days of physical, mental, or activity limitations per month [26]. Although a standard approach to dichotomize these number of days variables is not available, we used 15 days as our cut-point to capture subjects with particular burden—that is, a report of experiencing health limitations for more than one half of the recall period. In addition to the HRQOL-4 questions, BRFSS also asked respondents how often they receive the social and emotional support that they need (sometimes/rarely/never vs. always/usually) and how satisfied they are with life (dissatisfied/very dissatisfied vs. satisfied/very satisfied).

Health Behaviors

Health behaviors assessed included self-reported smoking status (current smoking some days/every day vs. never) and diet. Diet was assessed by a measure that summarized consumption of fruit juices, fruit, green salads, potatoes (not including potato chips, french fries, or fried potatoes), carrots, and other vegetables. This information was used to calculate the typical number of fruits and vegetables consumed per day (≥5 vs. <5).

Health Care Access and Utilization

All respondents (both survivors and control participants) answered questions about health insurance coverage, having a medical provider, cost-related health care barriers in the past year, and their health care utilization (e.g., routine checkups in the past 2 years). In 2010, Utah included BRFSS’ cancer survivorship module. In addition to the cancer survivorship questions asked in 2009, individuals who self-identified as a cancer survivor were asked if they were currently undergoing cancer therapy and what type of doctor provides the majority of their health care. They were also asked if they had ever received a written summary of their cancer treatments or if they were ever denied health insurance or life insurance coverage because of their cancer.

Statistical Methods

Data from 2009 and 2010 surveys were combined for analysis. To obtain estimates of population percentages and confidence intervals for this combined multi-year dataset, a complex survey weighting methodology provided by Utah Department of Health (UDOH) was used. New weighting and stratum variables were created based on guidelines received from the UDOH to ensure correct weighted estimates and valid confidence intervals for this combined multi-year data set.

Raw frequency and survey weighted percentages were calculated to describe demographic characteristics and cancer-related factors. A survey weighted Pearson chi-square test compared distributions between the survivors and controls. Multivariable survey weighted logistic regressions and computed predictive marginals estimated age-adjusted percentages and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) of health status, quality of life, health behaviors, and current health care associated outcomes by survivors and controls. As smoking and diet differ by gender [27], we investigated these outcomes in stratified models. Data were processed in SAS 9.4 using code provided by BRFSS. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 13.1. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05; all p values represent two-sided comparisons.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of survivors and controls are presented in Table 1. The survivor group was 41.7 % male compared with 50.3 % of the control group (p = 0.03). Survivors were older, with approximately 85 % ≥40 years old compared with 47 % of controls (overall p < 0.001). Most respondents were non-Hispanic white (95.3 % of survivors, 84.1 % of the control group, overall p < 0.001). The largest shift in ethnicity was the larger Hispanic population in the controls. Employment status differed between the groups, especially with the higher percentage of retired survivors (overall p < 0.001). Reported household incomes <$75,000 per year was more common among survivors compared to the control group, although not statistically significant (63.9%vs. 55.1 %, respectively, overall p = 0.07).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Utah cancer survivors and controls: Utah BRFSS 2009–2010

| Survivors | Controls | p valuec | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Na | Col. (%)b | Na | Col. (%)b | ||

| Gender | 0.03 | ||||

| Male | 283 | 41.7 | 4571 | 50.3 | |

| Female | 444 | 58.3 | 6022 | 49.7 | |

| Current age | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–29 | 9 | 6.1 | 1135 | 28.2 | |

| 30–39 | 37 | 9.0 | 2154 | 24.5 | |

| 40–64 | 257 | 35.3 | 5174 | 37.3 | |

| ≥65 | 424 | 49.6 | 2130 | 10.0 | |

| Computed race groups | <0.001 | ||||

| White/non-Hispanic | 694 | 95.3 | 9529 | 84.1 | |

| Black/non-Hispanic | 1 | 0.1 | 30 | 0.4 | |

| Hispanic | 13 | 1.9 | 624 | 11.0 | |

| Other/non-Hispanic | 11 | 2.2 | 264 | 2.9 | |

| Multiracial/non-Hispanic | 6 | 0.5 | 84 | 1.0 | |

| Missing/don’t know | 2 | 0.1 | 62 | 0.7 | |

| Education | 0.27 | ||||

| <High school | 48 | 16.9 | 544 | 15.2 | |

| Grade 12 or GED | 193 | 18.1 | 2869 | 25.3 | |

| College 1–3 years | 259 | 33.7 | 3580 | 34.5 | |

| College 4 years or more | 227 | 31.3 | 3576 | 24.9 | |

| Missing/don’t know | 0 | 0.0 | 24 | 0.2 | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | ||||

| Employed | 249 | 34.7 | 6162 | 60.2 | |

| Out of work | 29 | 4.4 | 553 | 8.6 | |

| Not in labor force | 77 | 11.0 | 1668 | 18.9 | |

| Retired | 324 | 38.5 | 1802 | 8.9 | |

| Unable to work | 46 | 11.3 | 383 | 3.1 | |

| Missing/don’t know | 2 | 0.1 | 25 | 0.4 | |

| Annual household income | 0.07 | ||||

| <$20,000 | 126 | 16.1 | 1066 | 11.9 | |

| $20,000–$49,999 | 257 | 34.4 | 3085 | 27.8 | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 100 | 13.4 | 1859 | 15.4 | |

| ≥$75,000 | 142 | 20.9 | 3301 | 28.6 | |

| Missing/don’t know | 102 | 15.2 | 1282 | 16.3 | |

Patients with missing/unknown age, cancer diagnosis <5 years, non-melanoma skin cancers were excluded from our analysis

Raw or unweighted response frequency

Weighted for BRFSS weight

p values were calculated from survey weighted chi-square test.

Characteristics of Cancer Survivors

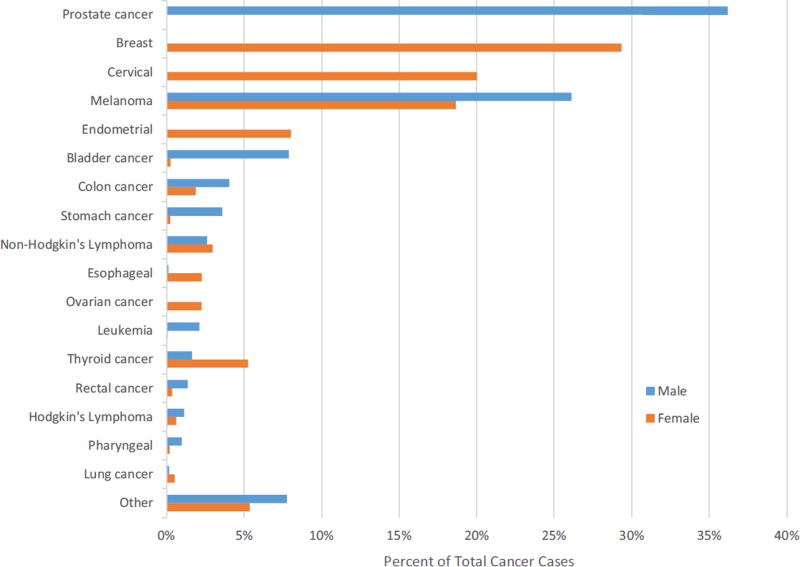

Prostate cancer (36.2 %, n = 100) was the most common type of cancer among male survivors and breast cancer (29.3 %, n = 146) among female survivors (Fig. 1). The prevalence of cancers by age of diagnosis peaked for male survivors between ages 60–69 (27.2 % of diagnoses, Table 2). The majority of females were diagnosed between the ages of 30–39 (19.3 %) and 40–49 (19.3 %). Most survivors reported only one cancer diagnosis (male 83.2 %, female 78.7 %) and most were survivors between 5–10 years since diagnosis (male 54.9 %, female 38.0 %). Ten percent of males and 20 % of females had survived over 25 years.

Fig. 1.

The percentages of self-reported initial cancer diagnoses from respondents in the Utah Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009–2010

Table 2.

Characteristics of Utah cancer survivors: Utah BRFSS 2009–2010

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Na | Col. (%)b | Na | Col. (%)b | |

| Age at diagnosis, years | ||||

| 1–17 | 7 | 5.9 | 9 | 9.9 |

| 18–29 | 15 | 11.3 | 73 | 17.1 |

| 30–39 | 23 | 9.7 | 85 | 19.3 |

| 40–49 | 42 | 13.1 | 90 | 19.3 |

| 50–59 | 75 | 21.0 | 81 | 13.8 |

| 60–69 | 74 | 27.2 | 64 | 12.8 |

| 70–79 | 43 | 11.4 | 38 | 7.2 |

| 80–97 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Number of cancer diagnosis | ||||

| 1 | 223 | 83.2 | 358 | 78.7 |

| ≥2 | 60 | 16.8 | 86 | 21.3 |

| Years since diagnosis | ||||

| 5–10 | 136 | 54.9 | 155 | 38.0 |

| 11–15 | 51 | 13.9 | 97 | 21.4 |

| 16–20 | 36 | 13.5 | 57 | 12.4 |

| 21–25 | 22 | 7.0 | 42 | 7.2 |

| 26–30 | 13 | 3.7 | 22 | 4.0 |

| ≥30 | 25 | 7.0 | 71 | 17.4 |

Patients with missing/unknown age, cancer diagnosis <5 years, non-melanoma skin cancers were excluded from our analysis

Raw or unweighted response frequency

Weighted for BRFSS weight

Health Status and Quality of Life

In age-adjusted proportions (Table 3), survivors reported poorer general health compared to controls (17.8 %, 95 % CI = 12.5–23.1 vs. 14.2%, 95%CI = 12.4–16.0). Of physical health, mental health, activity limitations, and life satisfaction, only life dissatisfaction had non-overlapping confidence intervals (survivors 10.5 %, 95 % CI = 5.4–15.7 vs. control 4.3 %, 95 % CI = 3.5–5.1).

Table 3.

Health status and health care access and use of Utah cancer survivors compared to controls, Utah BRFSS 2009–2010

| Survivors | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| %a | 95 % CI | %a | 95 % CI | |

| Health Status | ||||

| Fair/poor general health status | 17.8 | 12.5–23.1 | 14.2 | 12.4–16.0 |

| ≥15 days of poor physical health per month | 16.9 | 9.9–23.9 | 8.7 | 7.3–10.1 |

| ≥15 days of poor mental health per month | 17.8 | 9.4–26.1 | 9.6 | 8.2–10.9 |

| ≥15 days of activity limitations per month | 11.6 | 5.2–18.1 | 5.0 | 4.2–5.9 |

| Sometimes/rarely/never have adequate social/emotional support | 16.7 | 11.4–21.9 | 19.1 | 17.1–21.2 |

| Dissatisfied/very dissatisfied with life | 10.5 | 5.4–15.7 | 4.3 | 3.5–5.1 |

| Health care access and use | ||||

| Uninsured | 8.7 | 4.0–13.3 | 19.3 | 17.3–21.3 |

| No medical provider | 12.9 | 6.9–19.0 | 24.9 | 23.0–26.9 |

| Cost-related health care barriers in past year | 13.7 | 8.3–19.0 | 16.3 | 14.5–18.1 |

| No routine checkup within 2 years | 17.2 | 10.5–23.7 | 29.0 | 27.0–31.1 |

| Not currently undergoing cancer therapy | 92.5 | 85.4–99.6 | –b | |

| Care managed by primary care physician or non-cancer specialist | 93.5 | 87.9–99.1 | –b | |

| Did not receive a cancer treatment summary | 71.1 | 59.2–82.9 | –b | |

| Denied insurance due to cancer history | 5.5 | 1.2–9.7 | –b | |

Patients with missing/unknown age, cancer diagnosis <5 years, non-melanoma skin cancers were excluded from our analysis

Adjusted for current age

Data not provided in these cells as these were questions only asked of cancer survivors in 2010

Health Behaviors

Age-adjusted smoking rates were similar between survivors and the control group (male survivors 14.2 %, 95 % CI = 2.8–25.7 vs. male control 13.0 %, 95 % CI = 10.7–15.3; female survivors 13.8 % 95 % CI = 6.2–21.5 vs. female control 7.6 %, 95 % CI = 6.1–9.1). Fruit and vegetable intake (less than five fruits/vegetables per day) was also similar (male survivors 89.2 %, 95 % CI = 84.6–93.8 vs. male control 87.9 %, 95 % CI = 86.2–89.6; female survivors 80.6 %, 95 % CI = 78.6–82.5 vs. female control 75.8 %, 95 % CI = 68.1–83.5).

Health Care Access and Utilization

Table 3 presents the health status and health care access and use among cancer survivors and the control group adjusted for age. An estimated 10.6 % greater percentage of the control group reported no current insurance coverage (19.3 %, 95 % CI = 17.3–21.3) compared to cancer survivors (8.7 %, 95 % CI = 4.0–13.3). Cancer survivors reported having a current medical provider (24.9 %, 95 % CI = 23.0–26.9) more often than the control group (12.9 %, 95 % CI = 6.9–19.0). The control group also reported higher proportions of cost-related barriers to health and absence of routine checkups within the past 2 years. For the items limited to the 2010 data for survivors, the vast majority reported that their care was managed by primary care physicians or non-cancer specialists (93.5 %, 95 % CI = 87.9–99.1). Furthermore, 71.1 % (95 % CI = 59.2–82.9) reported not being provided a cancer treatment summary, and only 5.5 % (95 % CI = 1.2–9.7) had ever been denied insurance due to their cancer history.

Discussion

To identify areas of improvement for access to care and quality of life, it is important to conduct state-level assessments of cancer survivors to identify areas of action for the NCCCP program and public health educational interventions. This statewide assessment of Utah is the first step in developing a robust research initiative in alignment with the NCCCP to better meet the needs of the growing population of cancer survivors in Utah. Analyzing Utah BRFSS surveys from 2009 and 2010, we found that Utah cancer survivors reported more life dissatisfaction than unaffected controls. Utah cancer survivors also reported that the majority of their care is managed by primary care physicians and the majority of survivors do not receive a treatment summary. However, Utah cancer survivors are also more likely to have a current medical provider as compared to unaffected controls as described in the results. This presents an opportunity to work with and educate primary care physicians in improving the care of cancer survivors.

Unlike other national studies [11, 24] that have demonstrated issues with access to care among survivors of cancer, survivors in Utah tended to report fewer health care access concerns, such as cost-related barriers to care, than adults without cancer. Yet, other care disparities do appear to exist in Utah, with fewer than 8% of cancer survivors having their long term care managed by cancer specialists, and over 70 % reporting never having received a summary of their cancer therapy. Despite the expanded insurance options in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) [28], disparities in access to care may continue to be issues and are important areas for future NCCCP and educational efforts.

Our study’s findings on health care following cancer treatment can be viewed within the context of the existing literature and expert recommendations for survivorship care. In the short term after the end of cancer treatment, many studies find that survivors see an oncologist or other cancer specialist for surveillance of second cancers or recurrence [29, 30]. However, in the long-term (5 years post-treatment), the majority of survivors transition back to a primary care physician or other non-cancer specialist [31] who may be less familiar with patients’ cancer-related health care needs. Since the seminal 2006 Institute of Medicine (IOM) [31] survivorship report, greater coordination between specialists and primary care providers has been promoted to ensure that the health needs of cancer survivors are met. The 2006 IOM report also recommended that each patient should receive a cancer treatment summary following treatment. Despite this recommendation, fewer than 5 % of oncologists are delivering such summaries to their patients [32] and nationally, only one-third of patients typically receive a treatment summary [12, 13]. We found that approximately 30 % of Utah cancer survivors reported receiving a written treatment summary, which is similar to these other assessments. Treatment summaries are an important tool to improve coordination of care and address survivorship needs that can improve quality of life. Given the largely rural population of Utah, many survivors may not have ready access to a cancer specialist for follow-up care and so a treatment summary may be an essential communication and educational tool for primary care providers. Equipping primary care providers with resources and education to address the needs of cancer survivors, including treatment summaries, is an important area of priority for Utah in the state’s cancer plan [17].

Smoking was reported by over 10 % of Utah survivors, which while still of concern, is lower than the U.S. average of 20.9 % in 2009 [18]. Although the smoking rate is low, it is alarming that health behaviors (diet, smoking) were similar among Utah survivors and unaffected controls. Because smoking is a modifiable health behavior and poses increased risk for cancer and other health comorbidities, it may be a particularly important public health target for cancer control efforts in Utah.

Based on the findings of the current study, there are several key surveillance recommendations for Utah and for other states considering the NCCCP program. While BRFSS’s cancer survivorship module is optional [29], we encourage policy makers to incorporate these measures into their statewide BRFSS assessment on a regular basis to understand the health-related burden of cancer in their state. Including the survivorship module is particularly important because the cancer population in the U.S. is expected to grow to 19 million by 2024 [1]. Since Utah assessed survivors in the BRFSS survey in 2009 and 2010, the Commission on Cancer has required accredited cancer programs to implement treatment summary distribution to at least 25 % of new survivors by 2016 [33]. The survivorship module through BRFSS could serve as a tool for evaluating these changes at the state level and for comparison across the nation.

The findings from the current study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. BRFSS may underrepresent hard-to-reach populations, including minorities and young adults [34], which could lead to an underestimation of the magnitude of health care access issues and health outcomes among Utah cancer survivors. Furthermore, for our data years of interest, BRFSS only included landlines; however, starting in 2011, cell phones have been included across all states and it will be important to examine how this change responses. While self-reported cancer history also has the risk of misclassification of cancers and non-cancers, BRFSS self-report is reasonably reliable [35].

The current study provides insight into important issues for cancer survivors in Utah. These data could inform future public health education programs that meet the needs of cancer survivors in Utah. As life dissatisfaction was more common among cancer survivors, psychosocial interventions for cancer survivors may be an important area to further explore. Ongoing research with a focus on Utah cancer survivors is needed. Continued public health surveillance of health-related survivor issues using BRFSS will be necessary in order to detect potential changes occurring over time. In addition, future studies on cancer survivors should include cancer stage and treatment information so that differences between the severity of illness and health-based outcomes among survivors can be examined. Future studies should also examine rural/frontier vs. urban access to care, the utilization of treatment summaries, and how to best facilitate using treatment summaries with primary care providers.

The results of the current study provide education for clinicians and public health professionals in Utah to target interventions at reducing health risks among cancer survivors, such as use of tobacco. In addition, it will be important to promote delivery of treatment summaries to cancer survivors in order to promote optimal health care and health outcomes for survivors in the long-term. Knowing that Utah cancer survivors are more likely to report life dissatisfaction, and that few see oncology specialists in the long-term, interventions and educational resources can be directed most effectively. Cancer survivors have a variety of health care needs; addressing those needs on a state level enables the most appropriate professionals to direct resources to the groups most in need, with the ultimate goal of improving survivors’ long-term health and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research comes from the Huntsman Cancer Institute’s Cancer Control and Population Sciences Program and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation. We also acknowledge the use of shared resources supported by P30 CA042014 awarded to Huntsman Cancer Institute. This work was also supported, in part, by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) K07CA196985 (Y.P.W.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We would like to thank the Utah Department of Health for their assistance with data acquisition.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society 2014 Cancer Treatment and Survivorship: Facts and Figures 2014–2015. [Accessed 20 Jan 2016]; http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042801.pdf.

- 2.Schootman M, Homan S, Weaver KE, Jeffe DB, Yun S. The health and welfare of rural and urban cancer survivors in Missouri. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E152. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linsky A, Nyambose J, Battaglia TA. Lifestyle behaviors in Massachusetts adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarleton HP, Ryan-Ibarra S, Induni M. Chronic disease burden among cancer survivors in the California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009–2010. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(3):448–459. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desmond R, Jackson BE, Hunter G. Utilization of 2013 BRFSS Physical Activity Data for State Cancer Control Plan Objectives: Alabama Data. South Med J. 2015;108(5):290–297. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes HM, Nguyen HT, Nayak P, Oh JH, Escalante CP, Elting LS. Chronic conditions and health status in older cancer survivors. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(4):374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(5):1050–1057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LeMasters T, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, Kurian S. A population-based study comparing HRQoL among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors to propensity score matched controls, by cancer type, and gender. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2270–2282. doi: 10.1002/pon.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips-Salimi CR, Lommel K, Andrykowski MA. Physical and mental health status and health behaviors of childhood cancer survivors: findings from the 2009 BRFSS survey. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(6):964–970. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yanick R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, Banegas MP, Davidoff A, Han X, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oancea SC, Cheruvu VK. Psychological distress among adult cancer survivors: importance of survivorship care plan. Support Care Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jabson JM, Bowen DJ. Cancer treatment summaries and follow-up care instructions: which cancer survivors receive them? Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(5):861–871. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiseman KP, Bishop DL, Shen Q, Jones RM. Survivorship care plans and time since diagnosis: factors that contribute to who breast cancer survivors see for the majority of their care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(9):2669–2676. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabroff K, Short PF, Machlin S, Dowling E, Rozjabek H, Li C, et al. Access to preventive health care for cancer survivors. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(3):304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Census Bureau. 2005 Interim State Population Projections. [Accessed 25 Mar 2016];2005 https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/state/projectionsagesex.html.

- 17.Utah Comprehensive Cancer Control Program and the Utah Cancer Action Network. 2016–2010 Utah Comprehensive Cancer Prevention and Control Plan: A roadmap for all those fighting cancer in Utah. [Accessed 23 Feb 2016];2016 http://www.ucan.cc/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/State-Cancer-Plan_Final_for-web-1-25-16.pdf.

- 18.Nguyen K, Marshall L, Hu S, Neff L. State-specific prevalence of current cigarette smoking and smokeless tobacco use among adults aged ≥18 years—United States, 2011–2013; Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2015;64(19):532–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2016 Skin Cancer Rates by State. [Accessed 20 Jan 2016]; http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/statistics/state.htm.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2016 United States Cancer Statistics: 2012 Cancer Types Grouped by State and Region. [Accessed 20 Jan 2016]; https://nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/cancersbystateandregion.aspx.

- 21.Howden LM, Meyer JA. 2011 Age and sex composition: 2010. [Accessed 20 Jan 2016]; http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf.

- 22.Palmer NR, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Aziz NM, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in patient-provider communication, quality-of-care ratings, and patient activation among long-term cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(36):4087–4094. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [Accessed 20 Jan 2016]; http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/.

- 24.Palmer NR, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Arora NK, Aziz NM, Blanch-Hartigan D. Impact of rural residence on forgoing healthcare after cancer because of cost. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(10):1668–1676. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2011 CDC HRQOL-14 "Healthy Days Measure". [Accessed 26 Jan 2016]; http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/hrqol14_measure.htm.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2000 Measuring healthy days: population assessment of health-related quality of life. [Accessed 11 July 2016]; http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/pdfs/mhd.pdf.

- 27.Xu F, Town M, Balluz LS, Bartoli WP, Murphy W, Chowdhury PP, et al. Surveillance for certain health behaviors among states and selected local areas—United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2013;62(1):1–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarazi WW, Bradley CJ, Harless DW, Bear HD, Sabik LM. Medicaid expansion and access to care among cancer survivors: a baseline overview. J Cancer Surviv. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0504-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Stewart SL, Buchannan N, Ekwueme DU, Hawkins NA, et al. Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2012;61(SS01):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chubak J, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Alfano CM, Rabin BA, Hornbrook MC, et al. Providing care for cancer survivors in integrated health care delivery systems: practices, challenges, and research opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3):184–189. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Smith T, Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, et al. Provision and discussion of survivorship care plans among cancer survivors: results of a nationally representative survey of oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1578–1585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Comission on Cancer. Cancer program standards 2012: ensuring patient-centered care. [Accessed 20 Jan 2016];2012 https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx.

- 34.Schneider KL, Clark MA, Rakowski W, Lapane KL. Evaluating the impact of non-response bias in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(4):290–295. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.103861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson DE, Holtzman D, Bolen J, Stanwyck CA, Mack KA. Reliability and validity of measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46(Suppl 1):S3–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]