Abstract

A number of methods to drive the round window (RW) using a floating mass transducer (FMT) have been reported. This method has attracted attention because the FMT is relatively easy to implant in the RW niche. However, the use of an FMT to drive the RW has been proven to produce low outputs at frequencies below approximately 1 kHz. In this study, a new tri-coil bellows-type transducer (TCBT), which has excellent low frequency output and is easy to implant, is proposed. To design the frequency characteristics of the TCBT, mechanical and electrical simulations were performed, and then a comparative analysis was conducted between a floating mass type transducer (like the FMT) and a fixed type transducer (like the TCBT). The features of the proposed TCBT are as follows. First, the TCBT's housing is fixed to the RW niche so that it does not vibrate. Second, the internal end of a tiny bellows is connected to a vibrating three-pole permanent magnet located within three field coils. Finally, the rim of the bellows bottom is attached to the end of the housing that hermetically encloses the three field coils. In this design, the only vibrating element is the bellows itself, which efficiently drives the RW membrane. To evaluate the characteristics of this newly developed TCBT, the transducer was installed in the RW niche of temporal bones and the velocity of the stapes was measured using a laser Doppler vibrometer. The experimental results indicate that the TCBT can produce 100, 111, and 129 dB SPL equivalent pressure outputs at below 1 kHz, 1–3 kHz, and above 3 kHz, respectively. Thus, the TCBT with one side coupled to the RW via a bellows will be easy to implant and offer better performance than an FMT.

Keywords: Tri-coil bellows-type transducer (TCBT), Round window (RW), Middle-ear implants

1. Introduction

Various kinds of hearing aids have been utilized to overcome hearing impairment in humans, and nowadays, many types of hearing aids are available for patients with different types of hearing loss. Recently, for the treatment of patients with severe conductive hearing loss or sensorineural hearing loss, middle-ear implants that mechanically drive the cochlea with tiny middle-ear transducers have been widely used (Backous and Duke, 2006; Bankaitis and Fredrickson, 2002; Haynes et al., 2009; Jenkins et al., 2004; Kim and Barrs, 2006). Because middle-ear implants provide high-quality speech discrimination, many reports suggest that most hearing-loss patients who receive implants are satisfied (Channer et al., 2011; Goode et al., 1995).

Currently, there are several types of middle-ear transducers available for middle-ear implants (Puria et al., 2013). These include the Vibrant Soundbridge® (VSB) and Carina®. The VSB, a MED-EL Inc. product, is the most widely used device for middle-ear implants (Fisch et al., 2001; Fraysse et al., 2001; Luetje et al., 2002). Generally, the floating mass transducer (FMT) of the VSB device is attached to the long process of the incus. However, recently an alternate method has been widely investigated in which an FMT is installed in the round window (RW) niche in order to stimulate the intact RW membrane, because this method can solve the problem of ossicular necrosis and is also useful in cases with no ossicles (Colletti et al., 2009; Lefebvre et al., 2009; Spindel et al., 1995).

According to several studies, this RW-drive method using an FMT has a notably low vibration output in low-frequency regions (Dietz et al., 1997; Nakajima et al., 2010; Salcher et al., 2014; Shimizu et al., 2011). An FMT consists of two parts, i.e., the magnet and its housing, and the ideal frequency characteristics emerge when these two parts have the same mass. However, the loading effect of the FMT increases with an increase in the degree of contact between the tissue and the outer housing. Thus, since the induced reaction force of the outer housing due to the vibration of the magnet is low at low frequencies, the gain attenuation is more significant at low frequencies than at high frequencies. These results indicate the need to develop an alternate more efficient transducer for RW stimulation than the FMT.

In this paper, we propose and implement the tri-coil bellows transducer (TCBT) as a new middle-ear RW transducer, as it has excellent low-frequency output and is easy to implant. This transducer consists of three cylindrical field coils, a three-pole magnet, and a miniaturized bellows. This scheme maximizes magnetic-field utilization efficiency and reduces the interference of environmental magnetic fields. To determine the drive-type of the proposed TCBT, we first performed mechanical and electrical simulations and then a comparative analysis of the floating mass type transducer and fixed type transducer. In addition, we evaluated the proposed TCBT and its vibration characteristics. Finally, by implanting the TCBT in cadaveric temporal bones, we verified that the proposed transducer shows improved performance in terms of frequency characteristics and vibration efficiency as compared to the FMT.

2. Design of a new transducer (TCBT) for driving the RW

2.1. RW-drive middle-ear implant and its transducer

An RW-drive middle-ear implant consists of a microphone, a signal-processing module, and a vibration transducer. A conceptual illustration is given in Fig. 1. The microphone converts the acoustic signal into an electrical signal, and the amplified signal is then applied to the vibration transducer implanted in the RW niche. The RW transducer then converts the electrical signal into a mechanical vibration, and this signal energy is transmitted to the cochlea via the RW membrane. The vibration output transducer is the most important element of the middle-ear implant, as it governs the efficiency of the entire device. Therefore, the vibration output transducer must have good mechanical properties and high vibration efficiency. In addition, it needs an optimal design such that it has frequency characteristics similar to those of the auditory pathway of the ear, and it should be stable at the smallest possible size.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual illustration of a middle-ear implant that drives the cochlear round window (RW).

There are two methods of driving the RW: fixed type drive and floating mass type drive. A representative example of floating mass type drive is the FMT produced by MED-EL, Inc. The volume of the FMT is small enough to install in the middle ear, and it is easy to implant. However, thanks to the prior investigations of pioneering scientists, many ENT doctors today try to implant the FMT in the RW position. Many papers have reported on methods of implanting the FMT in the RW niche (Arnold et al., 2010a, 2010b; Colletti et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2006; Pennings et al., 2010; Skarzynski et al., 2014), and the process generally involves wrapping the FMT using biological fascia so that it can maintain proper contact with the RW membrane and then positioning it in the niche of the RW. However, according to the results of Nakajima et al. (2010) and Shimizu et al. (2011) studies on RW implantation using an FMT, the gain towards frequencies well below 1 kHz is poor, which may lead to insufficient amplification. Thus, frequencies starting from about 100 Hz are important for perceived naturalness of speech (Moore and Tan, 2003). A well-known example of the fixed type driving method is the Carina system developed by Cochlear, Ltd. (Tringali et al., 2009, 2010). This fixed-type system has better output characteristics at low frequencies than the FMT. However, its transducer is too large to be implanted in the middle-ear cavity, so it must be installed in the drilled wall of the temporal bone instead. Additionally, so far, there have been few clinical reports on RW stimulation using this fixed type transducer of Cochlear Ltd.'s middle-ear implant.

2.2. A comparison of floating mass type and fixed type drive methods

Generally, for RW stimulation in middle-ear implants, RW-drive methods are classified as either floating mass type or fixed type. As shown in Fig. 2(a) for the floating mass type method and Fig. 2(b) for the fixed type method, if we assume the two methods have the same coil and magnet mass, then with the same input current, they both produce the same electromotive force. In addition, we assume the elastic material of the floating mass type and the membrane of the fixed type have the same stiffness. In the case of Fig. 2(b), this force drives the magnet and rod (rigid material) only. However, in the case of Fig. 2(a), it should drive the entire mass of the transducer, including the housing and magnet. In other words, with the same driving force, due to the mass of the housing the mechanical load of Fig. 2(a) is greater than that of the fixed housing case in Fig. 2(b). Therefore, the vibration efficiency of the fixed type transducer is expected to better than that of the floating mass type transducer.

Fig. 2.

(a) Floating mass type driving method, and (b) fixed type driving method.

2.2.1. Analysis of characteristics of the floating mass type transducer

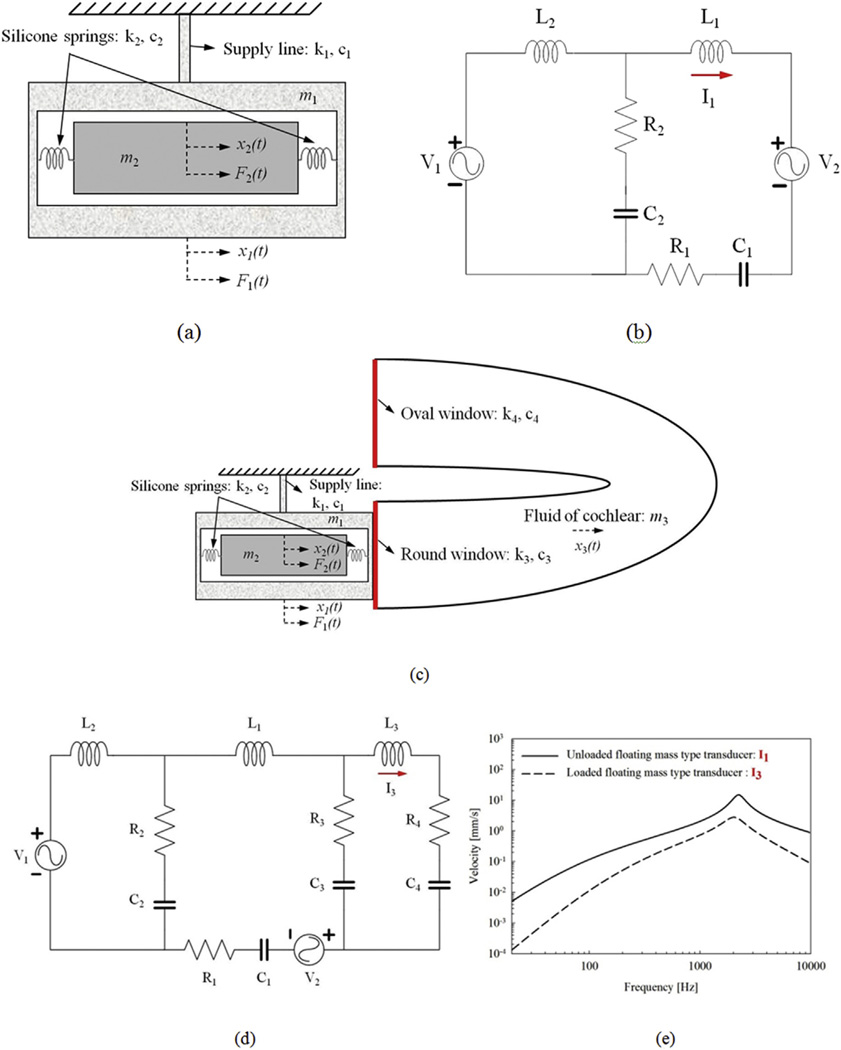

A simple equivalent mechanical model of the floating mass type transducer is shown in Fig. 3(a). This shows that when the floating mass type transducer is in the no-load condition (i.e., when there is no mechanical contact between the biological element and the floating mass type transducer), the theoretically calculated amplitude of the vibration displacement is given by the following equation (Kim et al., 2006a, 2006b):

| (1) |

Where

Fig. 3.

(a) Mechanical model of floating mass type transducer, (b) electrical analog model of a floating mass type transducer, (c) mechanical model of floating mass type transducer installed in the RW, (d) electrical analog model of a floating mass type transducer installed in the RW, and (e) comparison of frequency characteristics between unloaded (solid line: I1) and loaded (dashed line: I3) floating mass type transducers.

Here, m1 is the total mass of the floating mass type transducer except for the magnet, m2 is the mass of the magnet, k1 is the spring constant of the floating mass type transducer's lead wire, k2 is the spring constant of the elastic material located on each side of the magnet, c1 is the viscous damping factor from the lead wire, c2 is the viscous damping factor from the elastic material, x1(t) and x2(t) are the vibrational displacements of the housing and the magnet of the floating mass type transducer, respectively, and f1(t) and f2(t) are the magnitudes of the electromagnetic forces on the housing and magnet, respectively. The mechanical model of the floating-mass type transducer is simplified with a spring and two masses, which correspond to the magnet and the housing with coil, respectively. The electromagnetic force is generated due to Lorentz force between the magnet and the current in the coil. This force applied between two masses is opposite directions to produce action and reaction forces of the same magnitude, which are represented by F1 and F2.

The viscous damping factor accounting for air resistance inside the actuator has been ignored. The vibrational displacements of the floating mass type transducer are defined by the following equation.

| (2) |

where F1 is the constant electromagnetic force of the housing, F2 is the constant electromagnetic force of the magnet, and ω is the circular frequency.

Fig. 3(b) shows the electrical-circuit of the impedance-type analogy of Fig. 3(a). By using the mechanical-electrical parameters conversion table (Table 1), each parameter in Fig. 3(a) can be expressed in Fig. 3(b). In Fig. 3(a), x1(t) denotes a vibrational displacement of the housing, which corresponds to the I1 in Fig. 3(b). A simple mechanical model of the floating mass type transducer installed in the RW is shown in Fig. 3(c). When we assume that the surface of one end of the floating mass type transducer's housing is in good contact with the RW membrane of the cochlea, the resulting load on the transducer is composed of the following: the spring constants and viscosity constants of the RW membrane, denoted by k3 and c3, respectively, and of the oval window (OW) membrane, denoted by k4 and c4, respectively, and the mass of the liquid in the cochlea, denoted by m3 (Feng and Gan, 2002). Fig. 3(d) shows the electrical-circuit of the impedance-type analogy of Fig. 3(c). By using the conversion table (Table 1), each parameter in Fig. 3(c) can be expressed as follows: Masses m1–m3 correspond to L1–L3, stiffnesses k1–k4 correspond to C1–C4, viscous damping factors c1–c4 correspond to R1–R4, and electromagnetic forces F1 and F2 correspond to V1 and V2, respectively. We used the same physical constants of the cochlea for these simulations as those in Feng and Gan (2002). The value of the parameters used in the circuit of Fig. 3(d) are as follows: V1 and V2: 780 mV, L1 and L2: 10 µH, L3: 30.65 µH, C1: 617mF, C2: 0.85 mF, C3:10.8 mF, C4: 10.8 mF, R1 and R2: 0.047 Ω, and R3 and R4: 0.171 Ω (Seong, 2009). The choice of parameters of the floating mass type transducer, especially the resistances, has been made in order to compare them with the simulation result of a fixed type transducer. Fig. 3(c), x3(t) denotes a vibrational displacement of the cochlear fluid and corresponds to the I3 in Fig. 3(d).

Table 1.

Mechanical versus equivalent electrical parameters (Welkowitz and Deutsch, 1976).

| Mechanical parameter | Electrical parameter |

|---|---|

| Force, F [N] | Voltage, V [V] |

| Velocity, v [m/s] | Current, I [A] |

| Viscous damping factor, c [N·s/m] | Resistance, R [Ω] |

| Mass, m [kg] | Inductance, L [H] |

| Stiffness, k [N/m] | Reciprocal of capacitance, C−1 [F] |

The results of simulating this model using Multisim 13.0 software (National Instruments Co., USA) are shown in Fig. 3(e) for the unloaded (solid line: I1) and loaded (dashed line: I3) cases. The values used for plotting Fig. 3(e) curves which correspond to the mechanically equivalent values of I1 and I3, which are also the current at L1 and L3 in Fig. 3(b) and (d), respectively. These results clearly show that the velocity amplitude decreases when we move toward either low or high frequencies from the peak velocity point, for both the loaded and unloaded cases. However, the amount of attenuation at low frequencies is somewhat greater than that at high frequencies, and the loaded amplitude is 22 dB lower than the unloaded case at 100 Hz. Therefore, it appears that if we apply additional mechanical load due to the fascia wrapping the floating mass type transducer, then the velocities at the lower and upper frequencies will exhibit even more attenuation.

2.2.2. Analysis of characteristics of the fixed type transducer

To determine the vibration characteristics of the fixed type transducer, we made an electro-mechanical model and then performed an analysis on it. The lumped mechanical model of the fixed type transducer is shown in Fig. 4(a). Using the mechanical model, we applied Newton's law and then found an equation of motion for the unloaded fixed type transducer given by:

| (3) |

where

and F1(t) is the magnitude of the electromagnetic force on the magnet, m1 is the mass of the magnet of the fixed type transducer, k1 is the stiffness of the membrane, c1 is the viscous damping factor from the air inside the fixed type transducer, and x1(t) is the vibrational displacement of the magnet. The vibrational displacement of the fixed type transducer is defined in Eq. (4), and the amplitude of the displacement is computed by this theoretical formula. In the following equation, the frequency characteristics of the fixed type transducer do not depend on the mass of the outer housing. Here, F1 is the constant electromagnetic force, and X1 is the constant vibrational displacement.

| (4) |

Fig. 4.

(a) Mechanical model of fixed type transducer, (b) electrical analog model of the fixed type transducer, (c) mechanical model of the fixed type transducer installed in the RW, (d) electrical analog model of the fixed type transducer installed in the RW, (e) comparison of frequency characteristics between unloaded (solid line: I′1) and loaded (dashed line: I′2) of the fixed type transducer, and (f) comparison of loading-effect characteristics between the floating mass type transducer (black dashed line: I3) and the fixed type transducer (red dashed line: I′2). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 4(b) shows the electrical-circuit of the impedance-type analogy of Fig. 4(a). The conversion method from the mechanical model to electric model is the same that for Fig. 3(a) to (b). In Fig. 4(a), x1(t) denotes a vibrational displacement of the magnet and corresponds to the I′1 in Fig. 4(b). A simple mechanical model of the fixed type transducer installed in the RW is shown in Fig. 4(c). The equivalent electrical model of the fixed type transducer coupled with the RW is shown in Fig. 4(d). The parameters of the fixed type transducer of the electrical model correspond to the parameters of the lumped mechanical model, and the parameters of the cochlea were the same as those in Fig. 3. The parameters used in the circuit model in Fig. 4(d) are as follows: V1: 780 mV, L1: 10 µH, L2: 30.65 µH, C1: 0.5 mF, C2: 10.8 mF, C3: 10.8 mF, R1: 0.047 Ω, R2 and R3: 0.171 Ω. In Fig. 4(c), x2(t) denotes a vibrational displacement of the cochlear fluid and corresponds to the I′2 in Fig. 4(d).

The vibrational characteristics of the fixed type transducer were also simulated using Multisim 13.0 for both the unloaded case (only fixed type transducer) and the loaded case (fixed type transducer coupled with the RW) in which the RW membrane is in contact with the end surface of the membrane. The results of simulating this model are shown in Fig. 4(e) for the unloaded (solid line: I′1) and loaded (dashed line: I′2) cases. The values used for plotting Fig. 4(e) curves which correspond to the mechanically equivalent values of I′1 and I′2, which are also the current at L1 and L2 in Fig. 4(b) and (d), respectively.

Additionally, the simulation results comparing the frequency responses of the floating mass type transducer and the fixed type transducer are shown in Fig. 4(f). The unloaded cases of the floating mass type transducer and fixed type transducer are represented by the black (I1) and red (I′1) solid lines in Fig. 4(f), respectively, for which the vibrational velocity of the fixed type transducer is 6 dB higher than that of the floating mass type transducer over the entire audible frequency range. The loaded cases for the floating mass type transducer and fixed type transducer, as implanted in the RW niche, are represented by the black (I3) and red (I′2) dashed lines in Fig. 4(f), respectively, for which the vibrational velocity of the fixed type transducer is attenuated below the corresponding unloaded curve by 6 dB at frequencies below the 2 kHz resonance frequency and by 20 dB above the 2 kHz resonance frequency. On the other hand, the loaded vibrational velocity of the floating mass type transducer over the entire frequency range was on average attenuated below the corresponding unloaded curve by 20 dB. Therefore, from the loaded curves of the floating mass type transducer and fixed type transducer, it is apparent that the attenuation of the floating mass type transducer in the low-frequency region (below 1 kHz) is greater than that of the fixed type transducer in the same frequency region.

The reason for the low-frequency characteristics of the floating mass type transducer, which is a weakness of the type, is as follows: when the drive current is applied to the floating mass type transducer, by Newton's law, the induced reaction force of the housing is proportional to the mass of the housing and its acceleration, which is the second derivative of the housing displacement caused by the action of the permanent magnet. Therefore, if the drive frequency decreases, even if the displacement is the same as at a higher frequency, the vibrational forces acting on the floating mass type transducer's housing will be more rapidly attenuated than the vibrational force acting on the fixed type transducer's membrane. Thus, for delivering the drive force to the RW membrane, a fixed type transducer is more effective than a floating mass type transducer, so we chose the former when designing a new RW transducer.

3. TCBT fabrication and experiments

3.1. Proposed bellows design

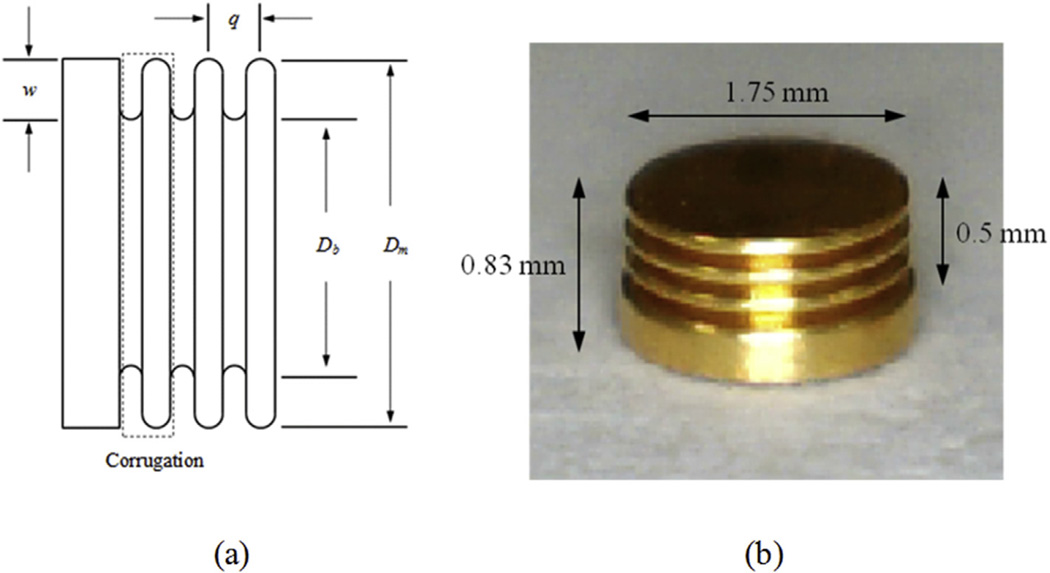

To actually design a fixed type transducer, we cannot use Fig. 4(a)’s configuration directly, because its thin vibrating membrane is attached to one end of the housing like the membrane of a flat drum, so displacements due to the membrane's vibration would be larger at the center but smaller near the rim. Thus, the vibrational efficiency of the flat membrane is not optimal. To solve this issue, we propose the bellows design shown in Fig. 5(a) as a way of efficiently transferring vibrational energy to the RW membrane.

Fig. 5.

(a) The structure of the proposed bellows, and (b) the implemented bellows.

The bellows is the most important element that affects the vibrational characteristics of the TCBT, as one can control the resonance frequency by changing its spring constant. The formula for the spring constant from the bellows structure is given by:

| (5) |

where, fiu is the spring constant of the bellows, Dm is the outer diameter of the bellows, Eb is the Young's modulus, tp is the bellows material thickness of one ply, n is the number of bellows material plies of thickness, w is the corrugation height, Cf is a factor used in the design calculations of the bellows, and N is the number of corrugations of the bellows (Robyr, 1999).

In the case of a TCBT that is attached to the RW, resonance characteristics must be generated near the 2 kHz band in order to obtain characteristics similar to natural middle-ear transmission. The geometric structure and the number of corrugations of the bellows change the stiffness, and thus change the characteristics of the transducer. The results of the simulation indicate that the optimum frequency characteristics of the bellows are as follows: a 68% ratio between the inner and outer diameters of the bellows, with a 7.6 µm thickness and three corrugations. In other words, with these parameters the bellows generated resonance characteristics near the 2 kHz band, and the vibrational velocity was maximized in the low-frequency region. Therefore, the actual bellows was implemented using these physical values. The material of the bellows was composed of pure-gold-coated nickel alloy, and the bellows was custom made at an expert bellows production company (Servometer Inc.). The implemented bellows, which has a diameter of 1.75 mm and a height of 0.83 mm, is shown in Fig. 5(b).

3.2. Fabrication of an RW-drive type TCBT

The TCBT consists of three field coils and two permanent magnets fused together at a common pole to make a three-pole magnet with an N-S-N or S-N-S structure, a tiny bellows, and a housing that will be placed in the RW niche. The three-pole structure of the magnet assembly makes it unsusceptible to environmental magnetic fields, such as a high-voltage electrical power system or having one's head touched with a strong permanent magnet. At the middle of the three-pole magnet's length, the magnetic field strength is at its strongest and the direction of the field is perpendicular to the axis of the magnet; therefore, to generate vibration force efficiently, the structure of the field coils must be appropriately designed. The field coils consist of one middle coil and two symmetrical side coils. The center of the middle coil length must exactly align with the center of the three-pole magnet. Additionally, the direction of the current in the middle coil is opposite to that in the side coils, so as to produce an axial force through the interaction between the three-pole magnetic fields that run opposite between the middle pole and each end of the magnet (Cho et al., 2012). To produce maximum force, the ratio of lengths among the three field coils is very important. Therefore, we performed a finite-element analysis (COMSOL Multi physics 5.0, COMSOL Inc.) to determine the optimal length of the three field coils, and found that the best length ratio that would provide the highest efficiency was 0.5 mm:0.8 mm:0.5 mm when the magnet length was 1.2 mm (Shin et al., 2015). The dimensions of the TCBT were determined according to the size of the RW niche area (Takahashi et al., 1989).

The TCBT, which has a diameter of 1.75 mm and a length of 2.3 mm, is shown in Fig. 6. The central coil and two side coils are wound in opposite directions. The three-pole permanent magnet (Sm2Co17), which consists of two magnets glued together at the same pole (D: 1.0 mm, L: 0.6 mm) is positioned inside the coils. The bellows was designed to have three corrugations, with an inner diameter of 1.21 mm, an outer diameter of 1.75 mm, and a bellows thickness of 7.6 µm. In addition, the bellows is directly connected to the three-pole magnet using a rod, which moves in response to the current in the field coils, and the flat outer surface of the bellows is in contact with the RW membrane.

Fig. 6.

Designed structure of the TCBT (left) and a photograph of a fabricated TCBT (right).

3.3. Measurements of TCBT vibrational characteristics

3.3.1. The characteristics of the TCBT

The vibrational velocity of the fabricated TCBT in the unloaded state on the bench was measured within the audible frequency range. SyncAv (v0.26; Stanford University, USA), an FFT-based data acquisition system, was used for all measurements. SyncAv used data acquisition hardware (an NI PXI-4461 board in an NI PXI-1042 chassis with an integrated controller; National Instruments Co., USA) to generate a stimulus signal to drive the TCBT, while synchronously measuring the velocity response of a reflector placed on the center of the bellows using a laser Doppler vibrometer (LDV; OFV-551 and OFV-5000; Polytec GmbH, Germany). The electrical resistance of the TCBT was approximately 300 Ω, and the unloaded vibrational velocity of the TCBT was measured with a 780 mV drive voltage to provide 2 mW of power. The measurements were performed at 66 logarithmically spaced frequencies in the 0.1–10 kHz range. The sampling rate was 96 kHz, the FFT length was 4096, and the measured LDV signal was synchronously averaged 10 times at each stimulus frequency. The measured frequency characteristics of the TCBT are shown in Fig. 7(a), and the resonance frequency of the TCBT is 2.2 kHz, which is equal to the simulated value. The measured velocity response shows a similar result, but is 3 dB lower than the simulated result.

Fig. 7.

(a) The unloaded vibrational characteristics of a circuit model response of the TCBT and a manufactured TCBT, (b) distortion characteristics of the TCBT under the unloaded condition, for three different input powers and (c) distortion characteristics of the TCBT with a 30 mg load on the bellows surface, for three different input powers.

Additionally, the distortion of the fabricated TCBT for performance verification was measured using a distortion meter (HM8023, HAMEG GmbH). In the no-load condition, meaning the end surface of the bellows was not in contact with any mass, the distortion level was below 0.5% in the frequency range of 1–10 kHz and the maximum distortion was 4.1% at resonance frequency (2.2 kHz) as shown in Fig. 7(b). And, the distortion of the TCBT was measured by placing a 30 mg mass, which is similar to the mass of the cochlear fluids (Feng and Gan, 2002), on the surface of bellows, and the result was below 0.8% distortion in the 1–10 kHz range as shown in Fig. 7(c). However, in the vicinity of the resonance frequency, which is reduced by 0.5 kHz from 2.2 kHz to 1.7 kHz due to the mass-loading effect, the maximum distortion was 1.2%. This is a lower value than the distortion of a conventional hearing aid receiver, which is typically 3–5% (Knowles Electronics, LLC; Simon, 1968).

3.3.2. Cadaveric experimental results

Experiments on cadaveric temporal bones (N = 5) were also performed to verify the effectiveness of the RW approach with the TCBT. The temporal bones used in the measurements were from a 58-year-old male (left ear: TB1, right ear: TB2), a 66-year-old female (left ear: TB3), a 44-year-old male (left ear: TB4), and a 34-year-old male (right ear: TB5) were all Caucasian and all acquired from the Anatomy Gifts Registry. The middle-ear cavity was opened using a posterior tympanotomy, and to achieve good TCBT positioning in the RW niche, any bony protrusion was removed in the hypotympanum. Tissue from the external ear canal was removed completely and replaced by an artificial ear canal consisting of a 30 mm long plastic tube, with the eardrum remaining intact. A sound-injecting tip was placed at the end of the plastic ear canal, and the probe microphone (ER-7C; Etymotic Research Inc., USA) tip was placed on the opposite side near the eardrum. Reflective beads were placed on the stapes footplate to improve the LDV signal, and the incident angle of the laser against the stapes footplate was kept above 60°. The surgical process of temporal bone dissection and TCBT implantation was conducted by the otologist (Kyu-Yup Lee).

The EQ function of SyncAv was calibrated to generate a constant ear canal pressure at the probe tube microphone location. The stapes velocities of the temporal bones in response to a 1 Pa (94 dB SPL) stimulus are shown in Fig. 8(a) for TB1–TB5, compared with the lower and upper limits (dotted black line) from ASTM-F2504 (ASTM International, 2005). The TCBT was placed in the RW niche, and the bellows side was placed against the RW membrane without any interposition of tissue, as shown in Fig. 8(b); the face of the bellows was in direct contact with the RW membrane. Then, TCBT positioning was carefully adjusted for inserting in the drilled space of the RW niche and ensuring that the other end of the TCBT housing contact with the protrude position of the end wall in the drilled volume. The vibration angle of TCBT was kept as perpendicular as possible with respect to the RW membrane to obtain the maximum stapes vibration. Once the TCBT was positioned, a small piece of fascia was placed behind the transducer for supporting the transducer and for stability during the experiment. The output characteristics of the TCBT with a driving force of 2 mW are shown in Fig. 8(c) as pink solid lines for the mean of TB1–TB5, with corresponding sound-driven results at 94 dB SPL shown with a black solid line. The outputs of the TCBT with a driving force of 2 mW were the equivalent of 100,111, and 129 dB SPL for frequency ranges of below 1 kHz, from 1 to 3 kHz and above 3 kHz, respectively.

Fig. 8.

(a) Temporal-bone stapes velocity measurements at 1 Pa (94 dB SPL), compared with the ASTM-F2504 standard, (b) photographs of the implantation process (left) and after TCBT implantation in the RW niche of a human cadaveric temporal bone (right), and (c) the measured stapes velocity of a TCBT for a 2 mW input (pink solid line), compared with the sound-driven results at 94 dB SPL (black solid line) (N = 5). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion and summary

In this paper, we proposed and implemented the TCBT as a new middle-ear transducer for driving the RW with improved low-frequency characteristics and higher efficiency. We analyzed and compared the vibrational characteristics of the floating mass type transducer and fixed type transducer through electro-mechanical modeling and measurements. The simulations of the unloaded vibrational characteristics show that the fixed type transducer has higher output than the floating mass type transducer across the whole frequency range (solid red line (fixed type) and solid black line (floating mass type) in Fig. 4(f)). The simulations suggest the loaded fixed type transducer's output velocity decreases by only 6 dB relative to the unloaded case at 100 Hz, whereas at the same frequency the loaded floating mass type transducer's output velocity decreases by more than 22 dB relative to the unloaded case (dashed red line (fixed type) and dashed black line (floating mass type) in Fig. 4(f)). In the high-frequency range, the two transducer types show similar attenuation characteristics in response to RW loading, but the attenuation of the fixed type transducer is slightly higher than that of the floating mass type transducer at 3 kHz.

Based on these simulation results, we developed a TCBT that has the potential for significantly greater low-frequency characteristics than an FMT. To evaluate this newly developed TCBT, the transducer was installed in the RW niche of five human cadaveric temporal bones and the velocity of the stapes footplate was measured. Based on the stapes velocity results in Fig. 9 (a), for acoustic drive at 94 dB SPL (black dashed line) and for RW stimulation by the TCBT with a 2 mW input (solid black line), the TCBT output corresponds to equivalent average pressure stimuli of 100, 111, and 129 dB SPL for frequencies below 1 kHz, from 1 to 3 kHz, and above 3 kHz, respectively. To investigate the TCBT's performance in relation to an FMT, a comparative evaluation was conducted. The red dashed line (Shimizu et al., 2011) represents the average stapes velocity due to an 80 dB SPL acoustic stimulation for eight temporal bones. An FMT was then implanted in the RW niche for each of those temporal bones and driven by 2 mW, which is the same power used to drive the TCBT. The stapes velocity as driven by the FMT was then measured and is shown as the red solid line in Fig. 9(a). The FMT implanted in the RW niche produced a stapes velocity equal to almost 100 dB SPL in the frequency range of 1–8 kHz (red solid line in Fig. 9(a)). The TCBT, in comparison, showed superior performance above 3 kHz, and the TCBT was also able to provide the equivalent of 100 dB SPL below 1 kHz (black solid line in Fig. 9(a)). Shimizu et al. (2011) did not report lower frequencies, so results from another study (Nakajima et al., 2010) are shown in Fig. 9(b) over the same frequency range as this study. In Nakajima et al. (2010), the FMT was implanted in the RW niche with the membrane intact, and over the 1–10 kHz frequency range the response due to a 100 mV stimulus was similar to the normal stapes velocity (ASTM-F2054) in response to 94 dB SPL, with a slope of −20 dB/decade in this range. On the other hand, the stapes velocity rolls off at a rate of −80 dB/decade as the frequency decreases below 1 kHz. From the above, we can see that driving the RW with a floating mass type transducer produces relatively poor results in the low-frequency region. However, low-frequency amplification is important in middle-ear implants, since they can be used to treat a mixture of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

Fig. 9.

(a) Comparison of equivalent SPL of TCBT (black) and FMT (red: from Shimizu et al., 2011) driven by 2 mW (Shimizu et al.), and (b) comparison of response tendency according to RW stimulation by TCBT (black) and FMT (red: from Nakajima et al., 2010). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The work needed to install the TCBT in the RW niche is easier than for other kinds of middle-ear transducers due to the following reasons. In the case of the Cochlear Ltd.'s middle-ear transducer, the body of the electromagnetic transducer is fixed to the superior medial wall of the middle-ear cavity using multiple screws, and then additional tuning work is needed to bring the ball tip into proper contact with the RW membrane (Tringali et al., 2010). However, the TCBT can be installed in the RW niche directly, similarly to how an FMT is installed in the RW niche. In fact, installing the TCBT requires drilling away a smaller volume of material around the margins of the RW niche than for installing an FMT. The extra marginal volume is needed because biological tissue, such as fascia, should wrap around the FMT to ensure that the FMT is operating under a floating condition within the drilled hole in the RW niche (Schwab et al., 2013). In the case of using a dedicated coupler for FMT installation, the coupler with the FMT must be wrapped using a patch of biological tissue to prevent the FMT from making direct contact with the bony structure of the RW niche. However, the TCBT does not need a large marginal volume and does not need to be wrapped with elastic biological tissue, unlike the FMT, because the cylindrical part of the TCBT, excluding the bellows, has to make firm contact with the bony structure of the RW niche. Thus, the surgical work required for TCBT implantation is much easier than for the other middle-ear transducers.

The difference between the resonance frequencies of the unloaded condition in Fig. 7(a) and those of the loaded conditions for temporal-bone experiments in Fig. 8(c) can be explained as follows. In unloaded condition, its resonance frequency is determined by mass of magnet and stiffness of bellows, giving 2.2 kHz. After the transducer was coupled with the RW, the resonance frequency is move to at around 4 kHz. It seems that the bellows is compressed by the fascia (behind the transducer) used for supporting the transducer, increasing stiffness of the bellows. Therefore, we presume that the increase of the resonant frequency as shown in Fig. 8(c) is responsible for this stiffness change.

When fixing the transducer in the RW niche, the fascia behind the transducer could act as a location for loss of driving force in this study. Thus, tissue that is more rigid such as small cartilage can achieve more efficient support to TCBT than the fascia can. More study is needed to find proper tissue or material behind TCBT to drive the RW membrane more efficiently. In addition, we need to develop supplementary mechanisms that can conveniently allow the cylindrical housing of the TCBT to form effective contact with the drilled hole of the RW niche without rolling, such that the surface of the bellows maintains proper contact with the RW membrane.

In this paper, we suggested a novel transducer for RW stimulation. It attaches to the RW via a tiny elastic bellows, and its non-vibrating side is fixed to the bone of the RW niche, allowing easy implantion. This scheme can offer better performance in terms of its frequency-response and power efficiency.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through a grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP) (No. 2013R1A2A1A09015677 and No. NRF-2016R1A2A1A05005413).

References

- ASTM International. Standard Practice for Describing System Output of Implantable Middle Ear Hearing Devices, Designation. 2005. pp. F2504–F2505. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold A, Kompis M, Candreia C, Pfiffner F, Häusler R, Stieger C. The floating mass transducer at the round window: direct transmission or bone conduction? Hear. Res. 2010a;263:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold A, Stieger C, Candreia C, Pfiffner F, Kompis M. Factors improving the vibration transfer of the floating mass transducer at the round window. Otol. Neurotol. 2010b;31(1):122–128. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181c34ee0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backous DD, Duke W. Implantable middle ear hearing devices: current state of technology and market challenge. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006;14(5):314–318. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000244187.66807.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankaitis AU, Fredrickson JM. Otologics middle ear transducer™ (MET™) implantable hearing device: rationale, technology, and design strategies. Trends Amplif. 2002;6(2):53–60. doi: 10.1177/108471380200600205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channer GA, Eshraghi AA, Zhong LX. Middle ear implants: historical and futuristic perspective. J. Otol. 2011;6(2):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cho JH, Lim HG, Seong KW, Lee JH. Three-coil Type Round Window Driving Vibrator Having Excellent Driving Force. 2012/0323066 A1. U.S. Patent. 2012

- Colletti V, Soli SD, Carner M, Colletti L. Treatment of mixed hearing losses via implantation of a vibratory transducer on the round window. Int. J. Audiol. 2006;45(10):600–608. doi: 10.1080/14992020600840903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletti V, Carner M, Colletti L. TORP vs round window implant for hearing restoration of patients with extensive ossicular chain defect. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129(4):449–452. doi: 10.1080/00016480802642070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz TG, Ball GR, Katz BH. Partially implantable vibrating ossicular prosthesis. Transducers'97: International Conference on Solid-state Sensors and Actuators; 1997. pp. 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Gan RZ. A lumped-parametric mechanical model of the human ear for sound transmissions. Proceedings of the Second Joint EMBS/EMES Conference; 2002. pp. 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Fisch U, Cremers CW, Lenarz T, Weber B, Babighian G, Uziel AS, Proops DW, O'Connor AF, Charachon R, Helms J, Fraysse B. Clinical experience with the Vibrant Soundbridge implant device. Otol. Neurotol. 2001;22(6):962–972. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200111000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraysse B, Lavieille JP, Schmerber S, Enée V, Truy E, Vincent C, Vaneecloo FM, Sterkers O. A multicenter study of the vibrant Soundbridge middle ear implant: early clinical results and experience. Otol. Neurotol. 2001;22(6):952–961. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200111000-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode RL, Rosenbaum ML, Maniglia AJ. The history and development of the implantable hearing aid. Otolaryngologic Clin. N. Am. 1995;28(1):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes DS, Young JA, Wanna GB, Glasscock ME. Middle ear of implantable hearing devices: an overview. Trends Amplif. 2009;13(3):206–214. doi: 10.1177/1084713809346262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins HA, Niparko JK, Slattery WH, Neely JG, Fredrickson JM. Otologics middle ear transducer ossicular stimulator: performance results with varying degrees of sensorineural hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124(4):391–394. doi: 10.1080/00016480410016298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer J, Arnold W, Staudenmaier R. Round window stimulation with an implantable hearing aid (Soundbridge) combined with autogenous reconstruction of the auricle - a new approach. J. Oto Rhino Laryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006;68(6):378–385. doi: 10.1159/000095282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HH, Barrs DM. Hearing aids: a review of what's new. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(6):1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Park IY, Song BS, Cho JH. Fabrication and optimal design of differential electromagnetic transducer for implantable middle ear hearing device. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006a;21(11):2170–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Yoon YH, Park IY, Cho JH. Design of differential electromagnetic transducer for implantable middle ear hearing device using finite element method. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2006b:130–131. 234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles Electronics LLC, Application Note AN-6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre PP, Martin C, Dubreuil C, Decat M, Yazbeck A, Kasic J, Tringali S. A pilot study of the safety and performance of the Otologics fully implantable hearing device: transducing sounds via the round window membrane to the inner ear. Audiol. Neurotol. 2009;14(3):172–180. doi: 10.1159/000171479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetje CM, Brackman D, Balkany TJ, Maw J, Baker RS, Kelsall D, Backous D, Miyamoto R, Parisier S, Arts A. Phase III clinical trial results with the Vibrant Soundbridge implantable middle ear hearing device: a prospective controlled multicenter study. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002;126(2):97–107. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.122182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BC, Tan CT. Perceived naturalness of spectrally distorted speech and music. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2003;114(1):408–419. doi: 10.1121/1.1577552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima HH, Dong W, Olson ES, Rosowski JJ, Ravicz ME, Merchant SN. Evaluation of round window stimulation using the floating mass transducer by intracochlear sound pressure measurements in human temporal bones. Otol. Neurotol. 2010;31(3):506–511. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181c0ea9f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings RJ, Ho A, Brown J, Wijhe RG, Bance M. Analysis of Vibrant Soundbridge placement against the round window membrane in a human cadaveric temporal bone model. Otol. Neurotol. 2010;31(6):998–1003. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181e8fc21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puria S, Richard RF, Arthur NP. The Middle Ear: Science, Otosurgery, and Technology. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robyr S. Master of Science Thesis. Helsinki University of Technology, Automation Engineering Department; 1999. FEM Modelling of a Bellows and a Bellows-based Micromanipulator. [Google Scholar]

- Salcher R, Schwab B, Lenarz T, Maier H. Round window stimulation with the floating mass transducer at constant pretension. Hear. Res. 2014;314:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab B, Grigoleit S, Teschner M. Do we really need a Coupler for the round window application of an AMEI? Otol. Neurotol. 2013;34(7):1181–1185. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31829b57c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong KW. Doctor of Engineering Thesis. Kyungpook National University Press; 2009. Prediction Model of Middle Ear Transfer Characteristics with Implanted Floating Mass Type Vibration Transducer for IMEHDs. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Puria S, Goode RL. The floating mass transducer on the round window versus attachment to an ossicular replacement prosthesis. Otol. Neurotol. 2011;32(1):98–103. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181f7ad76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DH, Lim HG, Seong KW, Lee JH, Kim MN, Cho JH. Design of a direct install bellows type EM transducer in round window for implantable middle ear hearing aids. Int. Conf. Inf. Convergence Technol. Smart Soc. 2015;1(1):174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Simon GR. Physical Performance of Hearing Aids as Affected by Receiver Substitution. Bulletin of Prosthetics Research; 1968. pp. 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Skarzynski J, Olszewski L, Skarzynski PH, Lorens A, Piotrowska A, porowski M, Mrowka M, Pilka A. Direct round window stimulation with the Med-El Vibrant Soundbridge: 5 years of experience using a technique without interposed fascia. Eur. Archives Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2014;271(3):477–482. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2432-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindel JH, Lambert PR, Ruth RA. The round window electromagnetic implantable hearing aid approach. Otolaryngologic Clin. N. Am. 1995;28(1):189–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Sando I, Takagi A. Computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction and measurement of the round window niche. Laryngoscope. 1989;99(5):505–509. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringali S, Pergola N, Berger P, Dubreuil C. Fully implantable hearing device with transducer on the round window as a treatment of mixed hearing loss. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36(3):353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringali S, Koka K, Deveze A, Holland NJ, Jenkins HA, Tollin DJ. Round window membrane implantation with an active middle ear implant: a study of the effects on the performance of round window exposure and transducer tip diameter in human cadaveric temporal bones. Audiol. Neurotol. 2010;15(5):291–302. doi: 10.1159/000283006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welkowitz W, Deutsch S. Biomedical Instruments: Theory and Design. Academic Press; 1976. pp. 23–27. [Google Scholar]