Abstract

Rationale

Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) are key players in maintaining immune homeostasis. Evidence suggests that Tregs respond to environmental cues to permit or suppress inflammation. In atherosclerosis, Th1-driven inflammation affects Treg homeostasis, but the mechanisms governing this phenomenon are unclear.

Objective

Here, we address whether atherosclerosis impacts Treg plasticity and functionality in Apoe−/− mice, and what effect Treg plasticity might have on the pathology of atherosclerosis.

Methods and Results

We demonstrate that atherosclerosis promotes Treg plasticity, resulting in the reduction of CXCR3+ Tregs, and the accumulation of an intermediate Th1-like IFNγ+CCR5+ Treg subset (Th1/Tregs) within the aorta. Importantly, Th1/Tregs arise in atherosclerosis from bona fide Tregs, rather than T effector cells. We show that Th1/Tregs recovered from atherosclerotic mice are dysfunctional in suppression assays. Using an adoptive transfer system and plasticity-prone Mir146a−/− Tregs, we demonstrate that elevated IFNγ+ Mir146a−/− Th1/Tregs are unable to adequately reduce atherosclerosis, arterial Th1, or macrophage content within Apoe−/− mice, in comparison to Mir146a+/+ Tregs. Lastly, via single cell RNA-sequencing and RT-PCR we show that Th1/Tregs possess a unique transcriptional phenotype characterized by co-expression of Treg and Th1 lineage genes, and a down-regulation of Treg-related genes, including Ikzf2, Ikzf4, Tigit, Lilrb4, and Il10. Additionally, an ingenuity pathway analysis further implicates IFNγ, IFNα, IL-2, IL-7, CTLA4, T cell receptor, and Csnk2b-related pathways in regulating Treg plasticity.

Conclusions

Atherosclerosis drives Treg plasticity, resulting in the accumulation of dysfunctional IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs that may permit further arterial inflammation and atherogenesis.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, inflammation, immunology, Treg, immune system, lymphocyte, plasticity, Animal Models of Human Disease, Basic Science Research

INTRODUCTION

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease in which the accumulation of modified lipoproteins within the arterial wall elicits a low-grade inflammatory response. Polyclonal CD4+ T-helper (Th) cell subsets are found within the aorta and play important modulatory roles throughout atherogenesis; although the specific arterial antigens that CD4+ T cells recognize are currently unclear.1,2 The majority of aortic CD4+ T cells are IFNγ+ and TNFα+ Th1 cells, which help to accelerate inflammation, lesion growth, and plaque instability.1,2 CD4+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) are also present within atherosclerotic plaques, where they play important roles in regulating inflammation.3,4 There are clear negative associations between the number of Tregs and atherogenesis,1,5-7 however it is unknown how atherosclerosis might affect the stability or plasticity of Tregs.

As a population, Tregs must prevent auto-immunity but allow beneficial pathogen- or damage-resolving immune responses to occur. In inflammatory, autoimmune, and lymphopenic contexts, subsets of Tregs may respond to environmental cues to partially or fully assume T effector-like phenotypes (‘Treg plasticity’), and/or lose Foxp3 expression and their suppressive functionality (‘Treg stability’).8-10 While the concept of Treg stability and auto-reactive ‘exTregs’ has generated debate, several groups have reported that Tregs may undergo limited plasticity; co-opting Teffector lineage factors to optimally suppress Teffector responses.11-15 For example, in the context of type 1 inflammation associated with infection, Tregs transiently produce IFNγ, and upregulate Tbet and CXCR3 in an IFNγR/IL-27R-STAT1-dependent manner. As a result, CXCR3+ Tregs migrate to and suppress Th1-dependent inflammatory foci,11,12 but fail to differentiate into Th1 cells.13 However chronic inflammation and excessive STAT1 activation can also result in the loss of Treg function, the generation of IFNγ-producing Tregs, and Th1-mediated pathology.16-18 For example, miRNAs critically support Treg development/homeostasis and Mir146a−/− mice display an age-dependent autoimmune syndrome that is characterized by concurrently elevated Stat1-dependent Th1-like IFNγ+ Tregs (termed “Th1/Tregs” hereafter) and Th1 cell responses.17,19 Thus Tregs may fine-tune their functionality in order to ultimately suppress or permit inflammation in various pathological states.

In the present study we examine the fates of Tregs in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice, to determine if atherosclerosis affects the stability, plasticity, or functionality of Tregs. We observe that atherosclerosis promotes the formation of an intermediately plastic Th1/Treg subset, characterized by IFNγ and CCR5 positivity. We demonstrate that Th1/Tregs are dysfunctional in suppression assays and are generated from bona fide Tregs in Apoe−/− mice. Furthermore, we demonstrate through the use of plasticity-prone Mir146a−/− Tregs that elevating Th1/Treg content fails to reduce atherosclerosis, arterial Th1, or macrophage accumulation in Apoe−/− recipients. Lastly, technological advances in the fields of single cell biology and genomic profiling have demonstrated that heterogeneity among individual cells can reveal a plethora of information about cell populations or subset.20,21 Here, we utilized single cell RNAseq (scRNA-seq) to examine the transcriptome of CCR5+ Th1/Tregs, in comparison to Tregs and Th1 cells. ScRNA-seq revealed that Th1/Tregs display reduced expression of immunosuppressive genes in comparison to Tregs, and have altered negative co-stimulatory molecule, transcriptional activity, glucocorticoid signaling, and migratory properties. Together, these data demonstrate that a subset of Tregs may undergo plasticity in atherosclerosis, resulting in the formation of a subset of non-suppressive Th1-like Tregs that are permissive of inflammation and atherogenic T cell responses.

METHODS

A fully-detailed description of all of the reagents and methods is available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Mice

Aged (40 weeks) and young (8-20 weeks) C57Bl6/J, Apoe−/−, Foxp3egfp/egfp, Foxp3yfp-cre/yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomatoApoe+/+, Foxp3yfp-cre/yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomatoApoe−/−, and Mir146a−/− mice were bred, and used for experiments at Eastern Virginia Medical School (Norfolk, VA) in accordance with IACUC Committee guidelines.

Flow cytometry

To prepare aortic cell suspensions, excised aortas were digested with 125 U/ml Collagenase type XI, 60 U/ml hyaluronidase type I-s, 60 U/ml DNAse1, and 450 U/ml Collagenase type I (Sigma-Aldritch, St. Louis, MO) for 1 hour at 37°C as we described.22 For intracellular staining, the suspensions were re-stimulated for 5 hours in RPMI-1640 containing 10ng/ml PMA, 500ng/ml Ionomycin C, and 600ng/ml Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldritch). The samples were acquired using an upgraded FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star Inc.). For all experiments, the gates were set based on isotype and/or fluorescent minus one controls.

Cell isolation procedures

For adoptive transfer and cell isolation experiments, CD4+ T cells were pre-enriched from spleens and PLNs using CD4+ cell isolation kits (Stemcell Technologies). Isolated CD4+ cells were stained for CD4, CD73, PD-1, CD25, CCR5, or isotype control antibodies, or used as is (Foxp3egfp/egfp, Foxp3yfp-cre/yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomato mice) for the experiments.

-

-

Apoe−/−CCR5+ Th1/Tregs: CD4+CD73++PD1+/++CD25+CCR5+ or Foxp3YFP-cre+CCR5+

-

-

Apoe−/−CCR5− Tregs: CD4+CD73++PD1+/++CD25+CCR5− or Foxp3YFP-cre+CCR5−

-

-

C57Bl/6 CCR5− Tregs: Foxp3eGFP+CCR5− or Foxp3YFP-cre+CCR5−

-

-

Apoe−/− Th1: CD4+CD73+/−CCR5+ or Foxp3YFP-cre−CCR5+

-

-

C57Bl6 Teff/N: CD4+Foxp3eGFP−

-

-

C57Bl6 Tregs: CD4+Foxp3eGFP+ or CD4+Foxp3YFP-cre+

-

-

scRNA-seq starting populations: CD4+CD73+/++PD1+CD25+CCR5+ (Apoe−/−) T cells.

Treg and Teff/naïve adoptive transfer fate tracing experiments

Splenic CD4+ T cells from 8-20 week Foxp3eGfp/eGfp mice or Foxp3Yfp-cre/Yfp-cre R26RtdTomato/tdTomato mice were FACS sorted to isolate C57Bl/6 Tregs and Teffector/Naïve (Teff/N) cells as IFNγ+Foxp3+ T cells are relatively rare in young mice. Purified Tregs were labeled with Cell Trace Violet (CTV, Life Technologies) and Teff/N cells were labeled with CFSE (Invitrogen). The labeled cohorts were injected (1-2×106 CTV+Foxp3YFP+R26RtdTomato+ Tregs/3 experiments) or co-injected (1-2×106 CTV+Foxp3eGFP+ Tregs and 10-20×106 CFSE+ Teff/N cells/mouse, 5 Apoe−/− and 3 C57Bl6 experiments) into 40wk-old Apoe−/− or C57Bl6 recipients. As negative controls, mice were injected with saline. Two weeks later, different organs were collected, and the donor Tregs and Teff/N cells were assessed for Foxp3 and IFNγ or CCR5 positivity.

T cell suppression assays

Splenic CD4+ T cells from 40 week-old Foxp3eGfp/eGfp mice, and Apoe−/− (experiments 1-4) or Foxp3Yfp-cre/Yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomatoApoe−/− mice (experiments 5 and 6) were isolated as CCR5+Foxp3+ Th1/Tregs are more abundant in aged mice. C57Bl/6 and Apoe−/− CCR5− Tregs, Apoe−/− CCR5+ Th1/Tregs, Th1, CD4+Foxp3− T responders (Tresp), and CD4− splenic APCs were isolated for the suppression assays. CFSE-labeled 5×103 Tresp cells were co-cultured with 0.1×106 APCs in RPMI1640, 0.5ug/ml anti-CD28, and 1ug/ml plate bound anti-CD3 (eBioscience) as a baseline. To compare the suppressive abilities of Apoe−/− and C57Bl/6 CCR5− Tregs, 5×103, 2.5×103, 1.25×103, or 0.75×103 Tregs were added to the Tresp cultures. 2-7×103 Apoe−/−CCR5+ Th1/Tregs were added to the Tresp cultures depending on the cellular yield. For the Th1-spike-in experiments, 5×103 Apoe−/− Th1 cells were spiked into a parallel set of C57Bl/6 CCR5− Treg dilution cultures. The cells were cultured for 4 days before being assessed for CFSE+ Tresp proliferation by FACS. As Apoe−/− Foxp3eGFPCCR5− Tregs (experiments 1-4), and Apoe−/− CCR5− Foxp3YFP-cre+ Tregs (experiments 4-5) were identical, the data from these experiments were combined for the final analysis.

Mir146a+/+ and Mir146a−/− adoptive Treg transfer experiments

Splenic CD4+CD25+ T cells from young, healthy C57Bl6 (Mir146a+/+) and Mir146a−/− mice were isolated and labeled with CTV (Week 0 injection cohort) or FarRed (week 4 injection cohort). The labeled cohorts were injected (1×106 labeled Tregs/genotype/Apoe−/− recipient) intravenously into aged 27 week-old Apoe−/− mice (n=5 males, 3-4 females/Treg genotype) at the start (week 0, CTV+ cells) and mid-way through (week 4, FarRed+ cells) (Fig.6A) to assess the effects of Treg plasticity on atherosclerosis. Age and diet-matched Apoe−/− mice injected with PBS served as a control cohort. After 8 weeks of WD feeding the aortas, hearts, spleens, PLNs, PALNs, carotid arteries, and blood were collected for en face lesion, MOVAT staining, flow cytometry, and plasma measurements.

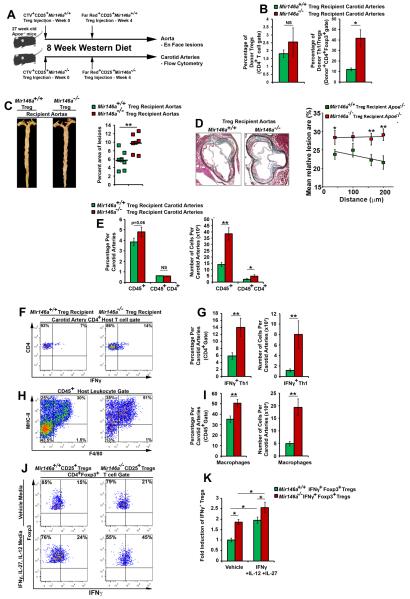

Figure 6. Th1/Treg-prone Mir146a−/− Tregs fail to reduce atherosclerosis and arterial inflammation in Apoe−/− mice.

(A) Experimental design. 27 week-old Apoe−/− littermates received 1×106 CTV-labeled Mir146a−/− or Mir146a+/+ Tregs and were subsequently placed on a WD regimen for 8 weeks (n= 5 male- and 3-4 female- Apoe−/− recipients/cohort). On week 4, both cohorts received an additional boost of 1×106 FarRed+ Mir146a+/+ or Mir146a−/− Tregs. Eight weeks later, the aortas, carotid arteries, lymphoid organs, and blood were collected. (B) Percentage of donor and IFNγ+ Mir146a+/+ and Mir146a−/− Tregs within 2-3 concatenated recipient Apoe−/− carotids (n=3 concatenated samples/genotype). (C) Representative Mir146a+/+ (Green squares) and Mir146a−/− (Red squares) Treg recipient Apoe−/− Oil Red O staining and lesion percentage of the aorta. (D) Representative MOVAT staining and the percentage of aortic root lesions in Mir146a+/+ and Mir146a−/− Treg recipient mice. (E-I) Representative flow cytometry results for the Treg recipient Apoe−/− carotid arteries. (E) The percentage and number of CD45+ leukocytes and CD45+CD4+ T cells within the Apoe−/− recipient carotid artery (two carotid arteries/recipient). (F, G) Representative host CD4+ T cell IFNγ FACS staining and quantification within the Apoe−/− Treg recipient carotids. (H, I) Carotid artery F4/80+MHC-II+ macrophage representative flow cytometry staining and quantification within the Apoe−/− recipients (n= 7-8 Apoe−/− recipients/Treg population, three independent experiments. (J, K) Mir146a−/− Tregs readily undergo plasticity in response to IL-27, IL-12, and IFNγ. CD25+ Mir146a+/+ and Mir146a−/− Tregs were isolated and cultured in complete RPMI1640 with CD3/CD28 antibodies, and IL-2 (50ng/ml, Vehicle), or IL-2, IL-12 (25ng/ml), IL-27 (25ng/ml), and IFNγ (25ng/ml) for 4 days and assessed for IFNγ+Foxp3+ Tregs Representative flow cytometry plots, (J) fold induction of IFNγ+ Tregs vs the Mir146a+/+ Treg vehicle controls. n = 3 independent experiments. The mean±SEM is shown. *-p<0.05, **-p<0.01, NS-Not significant, unpaired, one-tailed Bonferroni-Holm-corrected student’s T tests.

Aortic lesion quantification

Briefly, the aortas were excised, fixed with 4%PFA, and stained with oil red O. The stained aortas were opened longitudinally and pinned. The hearts were also collected and sequential 5 μm aortic root sections were cut from the point of appearance of the aortic valve leaflets. Three 5μm aortic root sections were analyzed by Movat staining as previously described.23 Images of the aortas and aortic roots were acquired and assessed for the percent surface area of lesions using ImageJ (v1.44).

Plasma cholesterol measurements

Plasma cholesterol of Mir146a+/+ and Mir146a−/− Treg Apoe−/− recipients was assayed using Total Cholesterol kits (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA).

In vitro T cell plasticity assays

1×105 CD25+ Tregs isolated from young Mir146a−/− and Mir146a+/+ mice were cultured in complete RPMI160 media supplemented with 50ng/ml IL-2 (Peprotech), 2μg/ml anti-mouse plate bound CD3, 0.5μg/ml anti-mouse CD28 antibody or with the addition of IL-12 (25ng/ml), IL-27 (25ng/ml), and IFNγ (25ng/ml). After 4 days in cultures, the cells were assessed for IFNγ+ and Foxp3+ expression by flow cytometry.

Quantitative real time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from sorted CCR5+ Tregs and CCR5− Tregs and contaminating genomic DNA was removed. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed, and RT-PCR was performed for Il10, Tgfb, Ebi3, and Actb. The results were normalized to Actb and data is presented as a fold change of the CCR5− Treg fraction, using the 2-δδCt method.

Single T cell RNA-seq experiments

20-30×103 Apoe−/− CD4+CD73+/++PD1+CD25+CCR5+ T cells (“scCCR5+ cells” hereafter) from 40 week-old Apoe−/− spleens (4-5 mice/experiment, n=6 independent experiments) were collected by sorting. This population contains a mixture of co-enriched Th1/Tregs (40-50%), Th1 (30-40%), and Tregs (10-20%). scCCR5+ cells were loaded onto a C1 Single-Cell Auto Prep IFC (Fluidigm), and reverse transcription, and cDNA pre-amplification was performed. 287 libraries yielded enough material for scRNA-seq and were pooled and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq (IGM Genomics Center, UCSD) to an average depth of 2.4±0.08×106 reads/library. Single-ended reads were demultiplexed and aligned to the Mus Musculus genome (UCSC) using FASTX (Hannon lab) and Tophat2 (Illumina BaseSpace). The resulting FPKM values were exported and aggregated for the final analyses using R and the SINGuLAR library. T cell groups were hierarchically clusted in silico based on Treg and Th1 lineage genes to yield a cohort of 21 Treg, 83 Th1, and 73 Th1/Treg libraries. Once defined, the groups were assessed for differential gene expression using R/SINGuLAR and ontology analyses were performed using DAVID (NIAID, NIH) and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen).

RESULTS

IFNγ-producing Foxp3+ Tregs are elevated in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice and display a Th1-like phenotype

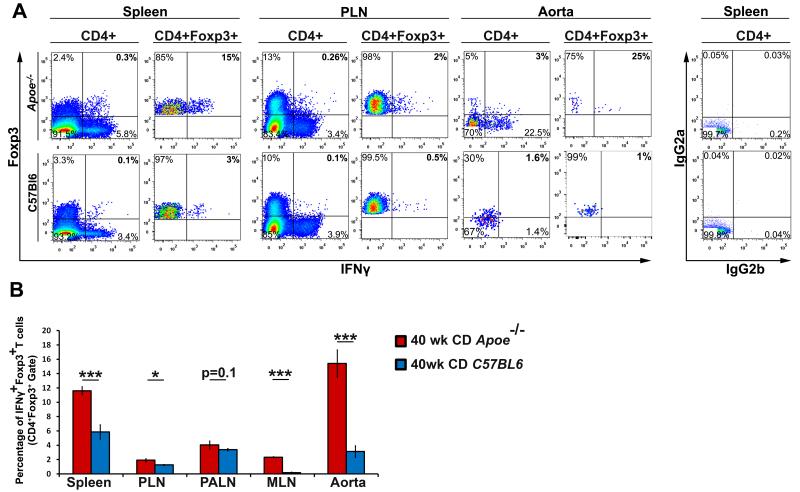

Tregs play critical roles in ameliorating atherosclerosis; however their overall numbers decline during atherogenesis.7 While the mechanisms behind this phenomenon are unclear, these changes can potentially be attributed to Treg phenotypic changes, lineage instability, or defective arterial recruitment.7,24 To determine if Tregs may display plasticity and assume a Th1-like state in atherosclerosis, we assessed Foxp3+ Tregs for IFNγ production (Fig.1, Online Figure I) in aged Apoe−/− and healthy C57Bl6 mice. IFNγ-producing Tregs were relatively rare (Fig.1A-B) in aged C57Bl6 mice, in agreement with prior C57Bl6 data.11,12,13 In contrast, IFNγ+Foxp3+ Tregs were significantly elevated in Apoe−/− mice (Fig.1A-B). To assess whether plastic IFNγ+ Th1/Treg cells are similarly present in the Ldlr−/− model of atherosclerosis, we analyzed spleens from high cholesterol diet fed Ldlr−/− mice and Apoe−/− mice and found similar percentages of Th1/Tregs in Apoe−/− and Ldlr−/− mice (10±1.2% and 8±0.65%, respectively, p=0.27). Thus our data suggest that atherosclerotic conditions may support the formation of IFNγ+ Tregs within the aorta and peripheral lymphoid organs.

Figure 1. INγ-producing Foxp3+ peripheral Tregs are present and systemically elevated within atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice.

Forty week old Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 splenic, PLN, PALN, MLN, and aortic cell suspensions were prepared and stained for ICS. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots and isotype controls for the spleen, PLN, and two pooled aortas of Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 mice are shown. All plots are gated on CD45+CD4+ T cells or CD45+CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs and the numbers in each quadrant indicate percentage. (B) The average percentage of IFNγ+ Tregs within Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 organs. n=12 mice/genotype, four independent experiments. The means±SEM are shown. ***-p<0.001, **-p<0.01, *-p<0.05, unpaired student’s T test.

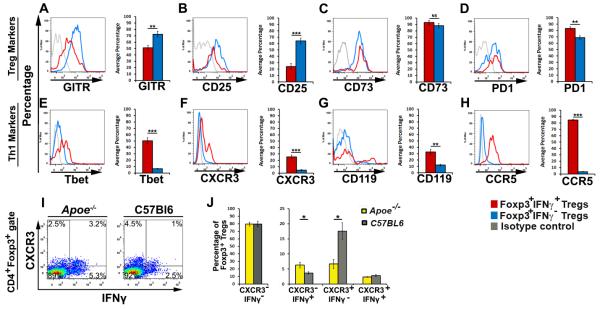

Activated Tregs have been reported to utilize Th1-lineage genes to migrate to and control sites of acute Th1-dependent inflammation, and some CXCR3+ Tregs may produce IFNγ.11-13 Therefore we hypothesized that Apoe−/− IFNγ+ Tregs might represent activated Th1-like Tregs and we examined the phenotypes of IFNγ-positive and negative Tregs in Apoe−/− mice (Fig.2).. IFNγ− Tregs from Apoe−/− spleens displayed a distinct phenotype characterized by high expression of the Treg markers: GITR, CD25, CD73, and PD-1 (Fig.2A-D), and negligible levels of the Th1 markers: Tbet, CXCR3, CD119, and CCR5 (Fig.2E-H). In contrast, IFNγ+ Tregs displayed a hybrid Th1-like Treg (“Th1/Treg”) phenotype in Apoe−/− spleens (Fig.2) and were predominately characterized as Foxp3high, IFNγintermediate-high, GITRlow, CD25low, CD73high, PD-1high, Tbetlow-intermediate, CXCR3negative-low, CD119low, CCR5high T cells (Fig.2).

Figure 2. Elevated IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs express heterogeneous levels of Treg and Th1 lineage markers in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice.

Forty week old Apoe−/− spleens (shown), PALNs, and aortas (not shown) were isolated and re-stimulated for ICS. CD45+CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs were gated and IFNγ+Foxp3+ (red histograms) and IFNγ− Foxp3+ (blue histograms) subgates were examined for the expression of the Treg markers GITR (A), CD25 (B), CD73 (C), and PD1 (D), and the Th1 markers Tbet (E), CXCR3 (F), CD119 (G), and CCR5 (H). All gates were set using isotype controls (gray histogram) and the percentages of positive cells are shown (means±SEM). (I-J) Aged Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 spleens (shown), PALNs, and aortas (not shown) were re-stimulated for ICS. CD45+CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs were gated and examined for IFNγ and CXCR3 expression. (J) The percentages of IFNγ and CXCR3 subsets amongst Foxp3+ Tregs from aged Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 spleens. The means±SEM are shown. n=8 mice, 4 independent experiments. ***-p<0.001, **-p<0.01, *-p<0.05, unpaired student’s T test.

CXCR3+ Treg homeostasis is negatively affected by atherosclerosis

CXCR3+ Tregs are protective in acute inflammation.11,12 We found a reduction in the proportion of atheroprotective CXCR3+ Tregs, but increased levels of CXCR3+IFNγ+ Tregs and IFNγ+CXCR3− Tregs in Apoe−/− mice (Fig.2I,J) suggesting that atherosclerosis negatively regulates homeostasis of protective CXCR3+ Treg. We also detected that the majority of Th1/Tregs do not express CXCR3, but expressed the chemokine receptor CCR5 (85±1.2%, Fig.2H). Interestingly, only some Th1/Tregs co-expressed CXCR3 and CCR5 (35±1.3%, not shown). This suggests that CCR5+IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs are elevated while protective CXCR3+ Tregs are slightly reduced in Apoe−/− mice. Therefore, we specifically focused on the biology of CCR5+IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs in atherosclerosis.

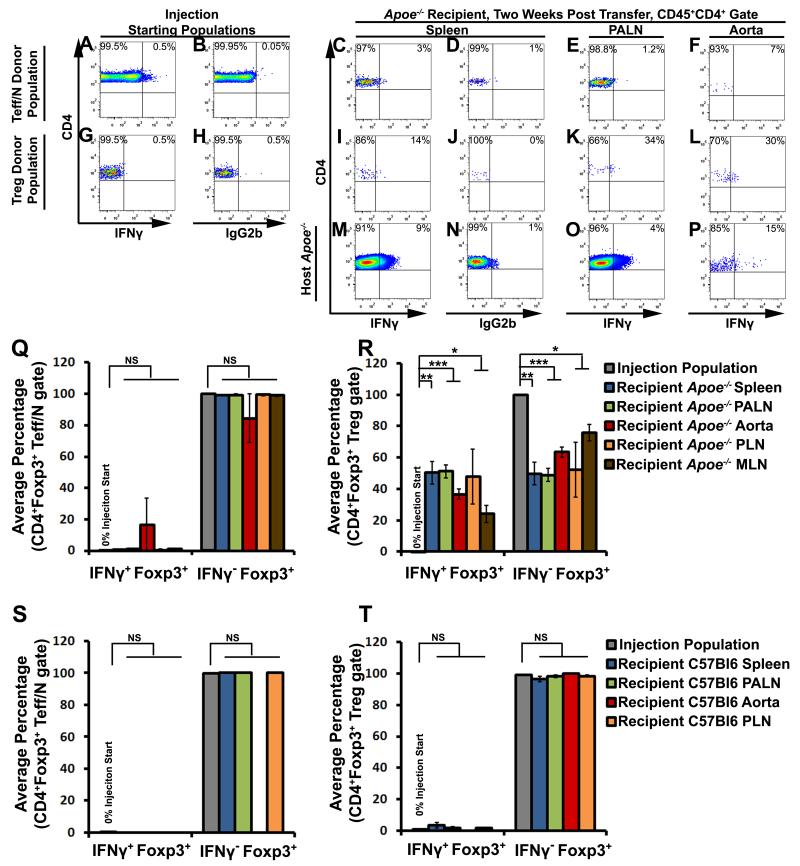

Atherosclerosis promotes Treg plasticity rather than Treg instability

Next, to examine the long-term fates of Tregs in atherosclerosis and the cellular sources of IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs, we performed a series of fate-tracking experiments. We first determined whether Th1/Tregs are generated in atherosclerosis from plastic Tregs or from phenotypically flexible T cells. As early Treg plasticity studies suggested that IFNγ+Foxp3+ T cells were activated T effector cells, it was important to test this possibility in atherosclerosis.9,10,25 To examine the sources of Th1/Tregs in vivo, CD4+Foxp3eGFP+ Tregs (Treg donor population) and CD4+Foxp3eGFP− T effector/naïve cells (Teff/N donor population) were separately labeled with CFSE or Cell Trace Violet (CTV), and co-injected into aged Apoe−/− recipients (Fig.3A-R). Neither the Teff/naïve (Fig.3A,Q) nor the Treg donor populations (Fig.3G,R) contained Foxp3+IFNγ+ cells prior to the injection. Two weeks post-transfer, the majority of donor Teff/N cells failed to become Tregs or Th1/Tregs (Fig.3C-F,Q). Conversely, the donor Tregs either maintained a Treg phenotype or ~30 % of Treg donor injected cells converted to an IFNγ+ Th1/Treg phenotype in aortas and PALN of recipients (Fig.3I-L, and R). Thus Tregs give rise to IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice.

Figure 3. IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs arise from bona fide Foxp3+ Tregs, rather than naïve or effector memory T cells, in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice.

Foxp3eGFP+CD4+ Tregs and Foxp3−CD4+ T effector/naïve cells (Teff/N) were sorted from eight-twenty week old Foxp3eGFP mice. Purified Tregs and Teff/N cells were separately labeled with cell trace violet or CFSE, mixed, and co-injected into aged Apoe−/− recipients. Two weeks post-transfer, the recipients were examined for the presence of IFNγ+ Tregs by ICS. (A,B,G,H) Representative CD4+ gated IFNγ and isotype control staining in the Teff/N (A,B) and Treg (G,H) donor populations, at the time of injection. (C-P) CD4-gated representative Foxp3 and IFNγ staining in the donor Teff/N (C-F), donor Treg (I-L), and the endogenous CD4+ Apoe−/− T cell (M-P) populations, based on population-specific isotype controls (D,J,N). (Q,R) The percentage of transferred Teff/N (Q) or Tregs (R) that converted to IFNγ+Foxp3+ or IFNγ−Foxp3+ Tregs in the spleen (blue), PALNs (green), aorta (red), PLNs (orange), or MLNs (brown) of recipient Apoe−/− mice (n=5), in comparison to the starting population (five independent experiments). Bars indicate the population means±SEM. (S,T) Analogous adoptive Foxp3−CD4+ Teff/naïve and Foxp3eGFP Treg transfers to 40 week old C57Bl6 recipient mice, as in (A-R). Percentage of IFNγ+Foxp3+ and IFNγ−Foxp3+ T cells within the donor Teff/N (S) or Treg (T) starting populations (gray), and recipient C57Bl6 spleens (blue), PALNs (green), aortas (red), and PLNs (orange) by ICS. n=3 recipients, three independent experiments. ***-p<0.001, **-p<0.01, *-p<0.05, Bonferroni-holm multiple comparison-corrected unpaired student’s T tests.

To test this phenomenon in non-atherosclerotic mice, analogous adoptive transfers were conducted using age-matched C57Bl6 mice (Fig.3S-T). In these experiments, both the Teff/Naïve (Fig.3S) and Treg (Fig.3T) donor populations failed to convert to Th1/Tregs. Thus, the pro-atherosclerotic conditions found in Apoe−/− mice drive the conversion of Tregs to an IFNγ+ Th1/Treg phenotype, in vivo.

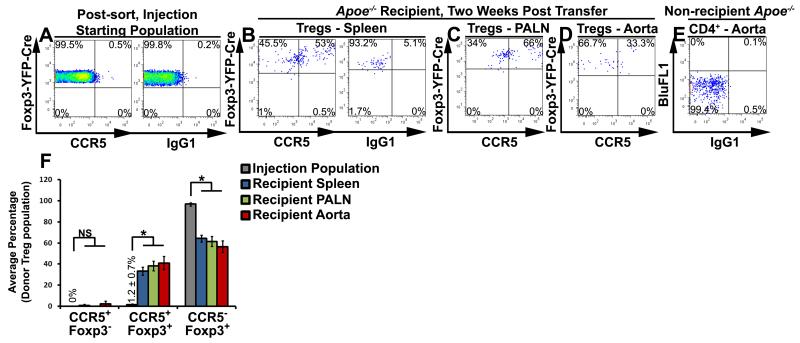

To confirm that atherosclerosis promotes Treg plasticity and to assess Treg stability, we generated Foxp3yfp-cre/yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomato mice. Briefly, in Foxp3-expressing cells, a Foxp3-dependent YFP-cre fusion protein irreversibly removes a loxP-flanked Stop cassette, allowing constitutive expression of the tdTomato reporter allele. Thus current (YFP+tdTomato+) and former (YFP−tdTomato+) Tregs can be distinguished. Based on the flow cytometric analysis, all current Tregs (CD4+Foxp3-YFP+) expressed tdTomato (data not shown). To track the fates of YFP+tdTomato+ Tregs in Apoe−/− mice, sorted Foxp3yfp-cre/yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomato Tregs were labeled and injected into aged Apoe−/− recipients (Fig.4). As CCR5 is highly expressed by Th1/Tregs (Fig.2H), CCR5 was used as an extracellular marker. While we detected CCR5+ T cells within the CD4+ pre-sort population (data not shown), we did not detect CCR5+YFP+TdTomato+ Tregs or YFP−tdTomato+ exTregs within the pre-injection isolates (Fig.4A,F). Two weeks post-transfer, the recipient Apoe−/− spleens, PALN, and aortas were assessed for CTV+CCR5+ donor Tregs (Fig.4B-F). Donor Tregs maintained detectable expression of both Foxp3YFP-Cre and TdTomato, suggesting that atherosclerosis does not destabilize Foxp3 expression to yield auto-reactive ‘exTregs’ (Fig.4F). In agreement with our results (Fig.3), YFP+tdTomato+ donor Tregs gave rise to CCR5+Foxp3YFP-Cre+TdTomato+ Th1/Tregs within the recipient spleens, PALN, and aortas (Fig.4B,C,E,F). Thus Tregs still express detectable levels of Foxp3 but may undergo plasticity in atherosclerosis, generating Th1/Tregs.

Figure 4. Adoptively transferred Tregs maintain stable Foxp3+ expression and assume a CCR5+ Th1/Treg or a CCR5− Treg phenotype in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice.

Foxp3Yfp-cre/Yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomato splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated from 8-20 week old mice and sorted for Foxp3yfp-cre+R26RtdTomato+ Tregs. Purified YFP-Cre+tdTomato+ Tregs were labeled with cell trace violet and injected into aged Apoe−/− recipients. Two weeks post-transfer, the recipients were harvested and examined for the presence of CCR5+ Th1/Tregs by flow cytometry. (A) Representative CCR5 and isotype control staining in the injection starting population. (B-E) Representative CCR5 staining in the recipient spleens (B), PALNs (C), and aorta (D), within the gated CTV+CD4+ donor cell population. (E) Isotype staining in a non-recipient Apoe−/− aorta. (F) The average percentage of transferred Tregs that assumed a CCR5+Foxp3−, CCR5+Foxp3+, or CCR5−Foxp3+ phenotype within the injection population (grey), recipient Apoe−/− spleen (blue), PALNs (green), and aorta (red). n=3 recipients, three independent experiments. ***-p<0.001, **-p<0.01, *-p<0.05, NS–not significant, Bonferroni-holm multiple comparison-corrected unpaired student’s T tests.

Plastic Th1/Tregs recovered from atherosclerotic mice are non-suppressive and fail to reduce atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice

In atherosclerosis, Treg functionality declines likely due to reduced expression of immunosuppressive co-stimulatory molecules and cytokines.7 We demonstrated here that atherosclerosis supports Treg plasticity in Apoe−/− mice, yielding a subset of plastic Th1/Tregs (Fig.3,4) that up-regulate Th1 and down-regulate Treg markers (Fig.2). However it was unclear whether plastic Th1/Tregs may still function as suppressive cells in atherosclerosis. To determine the functionality of Th1/Tregs, we assessed their ability to suppress T cell responses in vitro and in vivo.

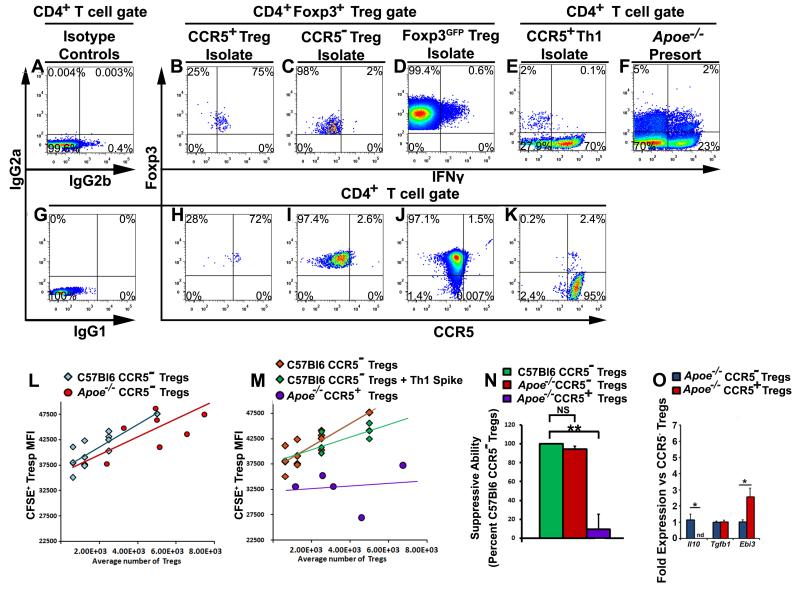

CCR5+ Th1/Tregs were sorted from aged Apoe−/− mice and CCR5− Tregs from age-matched Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 mice for direct comparisons in T cell suppression assays (Fig.5, Online Figure II). To control the quality of the suppression assays, we assessed the post-sort purity of all populations by ICS (Fig.5B-F) or CCR5 staining (Fig.5H-K). Apoe−/− (Fig.5C,I) and C57Bl6 (Fig.5D,J) CCR5− Tregs, and CD4+Foxp3− T cells (plots not shown) were purified to ≥98% purity and CCR5+ Tregs (Fig.5B,H) were enriched from 0.5-2% to 70-80% purity for the assays. In the suppression assays, phenotypically identical C57Bl6 and Apoe−/− CCR5− Tregs were equally suppressive (Fig.5L,N) while CCR5+ Th1/Tregs were comparatively non-suppressive (Fig.5M,N). Since we enriched CCR5+ Th1/Tregs to 70-80% purity, we controlled for the possibility that elevated IFNγ-production or co-enriched Th1 cells might have affected Th1/Treg-mediated suppression. Co-isolated CCR5+ Th1 cells from Apoe−/− mice were spiked into a separate set of C57Bl6 CCR5− Treg dilutions and compared with non-spiked Tregs (Fig.5E,K,M, Online Figure 2). The addition of Th1 cells to the cultures failed to antagonize T cell suppression to the same extent as Apoe−/− Th1/Tregs (Fig.5M), suggesting that CCR5+ Th1/Tregs are dysfunctional.

Figure 5. CCR5+ Th1/Tregs isolated from aged Apoe−/− mice are non-suppressive, ex vivo.

Splenic CD4+ T cells were isolated from aged Apoe−/−, Foxp3eGFP, or Foxp3Yfp-cre/Yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomato Apoe−/− and Foxp3Yfp-cre/Yfp-creR26RtdTomato/tdTomato C57Bl6 mice and the following subsets were purified for T cell suppression assays: CCR5− Tregs, CCR5+ Th1/Tregs, Foxp3eGFP+ Tregs, CCR5+ Th1, CD4+Foxp3− CFSE-labeled T responders (Tresp), and CD4-depleted splenocytes (APCs). (A-K) Representative IFNγ, Foxp3, CCR5, or isotype control staining. Isotype controls for IFNγ (A), and CCR5 (G). IFNγ staining within CD4+Foxp3+-gated Apoe−/− CCR5+ Th1/Treg (B), CCR5− Treg (C), C57Bl6 Foxp3GFP+ Treg (D), Apoe−/− CCR5+ Th1 (E) post sort isolates, and the CD4+ Apoe−/− pre-sort population (F). (H-K) Representative CCR5 staining for CCR5+ Th1/Treg (H), CCR5− Treg (I), C57Bl6 Foxp3GFP+ Treg (J), and CCR5+ Th1 (K) post sort isolates. (L,M,N) T cell suppression assay results. Comparison of (L) Apoe−/− and C57Bl6 CCR5− Tregs, (M) C57Bl6 CCR5− Tregs, C57Bl6 CCR5− Tregs spiked with Apoe−/− Th1 cells, and Apoe−/− CCR5+ Th1/Tregs in the suppression assays. (N) The mean suppressive ability of Apoe−/− CCR5− Tregs and Apoe−/− CCR5+ Th1/Tregs as a percentage of C57Bl6 CCR5− Treg suppression (n=6 independent experiments). (O) Sorted CD4+Foxp3+CCR5+ Tregs (Treg/Th1) and CD4+Foxp3+CCR5− Treg cells from aged 40 week-old chow diet Foxp3Yfp-cre/Yfp-CreR26RtdTomato/tdTomatoApoe−/− mice were processed for Il10, Tgfβ, and Ebi3 expression (n=4/ per cell type). The mean±SEM is shown. **-p<0.01, NS–not significant, Bonferroni-holm-corrected unpaired student’s T tests.

Next, to explore a mechanism by which CCR5+ Th1/Tregs possess non-suppressive phenotype, we analyze the expression of immunosuppressive cytokines Il10, Tgfb and Il35 by CD4+Foxp3+CCR5+ Tregs (Treg/Th1) and CD4+Foxp3+CCR5− Tregs isolated from aged Apoe−/− mice. Treg/Th1 cells did not express Il10 but did still express Tgfβ, and show elevated expression of Ebi3 in comparison to suppressive CCR5− Tregs (Fig.5O) suggesting that reduced Il10 expression in the conjunction with the reduced levels of negative co-stimulatory molecules (Fig.2 and 7) might be responsible for dysfunctional phenotype of Treg/Th1 cells. While the elevated Ebi3 expression data are interesting and may potentially reflect a compensatory mechanism, our flow cytometry, RNAseq (Fig.7), RT-PCR phenotyping and cellular assays of Th1/Tregs is consistent with a non-suppressive role for these cells, suggesting that the upregulation of Ebi3 is insufficient to restore the suppressive functionality to Th1/Tregs.

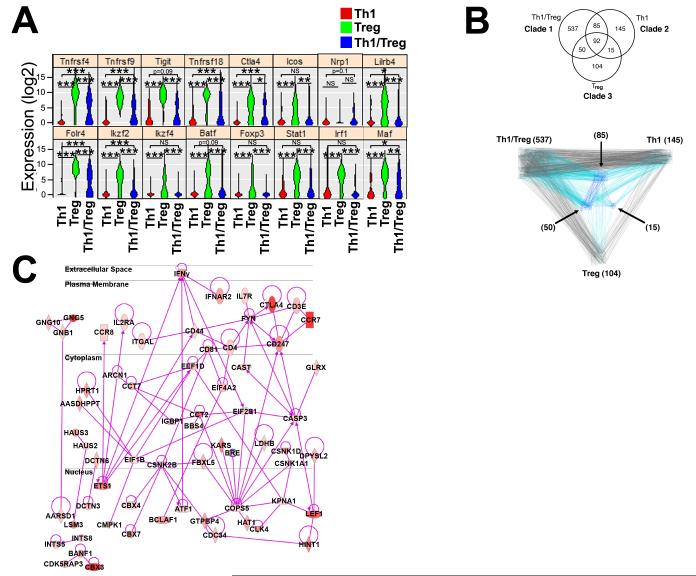

Figure 7. scRNA-seq reveals down-regulation of multiple Treg immunosuppressive genes within plastic Th1/Tregs.

Sorted 40 week old Apoe−/− splenic CD4+CD73+PD1+CD25+CCR5+ T cells were used to create single cell libraries for Fluidigm C1-based SMARTer RNA-Seq (Supplemental Fig. 3, n=3-4 mice/experiment, 6 experiments, 270 single T cell libraries). The sequenced, processed single T cell libraries were hierarchically clustered into Th1 (red, n=83), Treg (green, n=21), and Th1/Treg (blue, n=72) cells and analyzed for differential gene expression. (A) Select significantly different violin plots are shown for each subset. (B-C) Summary of the IPA-based re-sorting and clustering. (B) A Venn diagram of genes with an expression level above 100 reads, and IPA generated connectivity among the categories of unique and shared genes for clades 1-3. (C) The 537 genes uniquely expressed by clade 1 were used to generate a predicted network that is highly expressed in Th1/Tregs. The average expression levels among a representative set of clade 1 cells is overlaid, with the intensity of red showing denoting higher FPKM counts. ***-p<0.001, **-p<0.01, *-p<0.05, NS–not significant, Tukey ANOVA post-hoc tests.

As Th1/Tregs are non-suppressive in vitro, we hypothesized that Th1/Tregs would fail to suppress arterial inflammation, allowing accelerated atherogenesis in Apoe−/− mice. To test this hypothesis, we adapted a Treg adoptive transfer protocol3 that clearly demonstrated an atheroprotective role for a small population of adoptively transferred Tregs. We reasoned that manipulating the levels of Th1/Tregs via plasticity-prone Mir146a−/− mice and their adoptive transfer into Apoe−/− recipients would be a reasonable approach to compare the effects of Th1/Tregs vs Tregs on atherogenesis. Thus CD4+CD25+ Tregs from Mir146a−/− and Mir146a+/+ mice were isolated for long-term adoptive transfer studies (Fig.6A). Prior to the injection, none of the donor Treg populations contained an appreciable amount of IFNγ+ Tregs. After an 8 week western diet (WD), the Apoe−/− recipients and an additional age- and diet-matched group of Apoe−/− mice were assessed for plaque development, and recipients were analyzed for carotid arterial inflammation, and for the presence of IFNγ+ donor Tregs (Fig.6A). Both subsets of donor Tregs were present within the recipient Apoe−/− carotid arteries, however carotid arterial Th1/Tregs were elevated fourfold within Mir146a−/− Treg-recipient Apoe−/− mice (Fig.6B). As expected the adoptive transfer of Mir146a+/+ Tregs resulted in attenuated plaque burden in Mir146a+/+ Treg-recipient Apoe−/− mice in comparison with age and diet-matched Apoe−/− controls (7.0% ±0.6% and 10.6%±0.9%, respectively, p=0.003). In contrast, Mir146a−/− Treg Apoe−/− recipients displayed elevated atherosclerotic lesions in aortas (Fig.6C) and aortic valves (Fig.6D), carotid arterial CD45+ and CD4+ cellularity (Fig.6E), IFNγ+ Th1 cells (Fig.6F-G), and F4/80+MHC-II+ macrophages (Fig.6H-I). The percent area of macrophages was also elevated in Mir146a−/− Treg-recipient compared with Mir146a+/+ Apoe−/− recipient mice (37.7±4.9% and 49.7 ±6.3, p=0.03, respectively). Notably, we did not detect any differences in total cholesterol (Online Table I). We next assessed the potential for Mir146a+/+ and Mir146a−/− Tregs to undergo plasticity in response to the pro-Th1 cytokines IL-12, IL-27, and IFNγ (Fig.6J, K). In response to a cytokine challenge, a portion of Mir146a+/+ Tregs converted to Th1/Tregs. Interestingly Mir146a−/− Tregs had elevated basal levels of Th1/Tregs in vitro, but also further converted to Th1/Tregs in response to the cytokine challenge, resulting in more Th1/Tregs overall. Thus inflammation during atherosclerosis supports the conversion of a subset Tregs to a dysfunctional Th1/Treg phenotype, which fails to suppress arterial inflammation during atherogenesis.

Single cell mRNA sequencing underscores a non-suppressive phenotype for Th1-like plastic Tregs

As Th1/Tregs are a subset of dysfunctional plastic Tregs that are unable to reduce atherosclerosis, we sought to gain further insight into their biology. We adapted a low-coverage scRNA-seq protocol26, 27 to further examine the phenotype of Th1/Tregs versus Tregs and Th1 cells. As the single T cell libraries contained a mixture of co-enriched Th1, Th1/Treg, and Tregs, we hierarchically clustered the libraries into major T cell groups (Online Figure III), based on the expression of known Th1 or Treg lineage-related genes (Online Supplement). Unstimulated Th1 libraries were characterized by low-negative expression of the Treg-related genes Tnfrsf4, Tnfrsf9, Tnfrsf18, Ctla4, Ikzf2, Ikzf4, Foxp3, and trended towards elevated expression of Th1 genes, including Id2, Ifng, and Tnf. Some Th1 lineage genes such as Tbx21, Ifngr1, Ifngr2, Il12rb1, Il12rb2, and Stat4 were not robustly expressed in all of the Th1 cell libraries, suggesting that single Th1 cells might require re-stimulation or TCR engagement to robustly express classic lineage genes.28 Similarly, individual Tregs displayed high expression of the Treg genes Tnfrsf4, Tnfrsf9, Tnfrsf18, Ctla4, Ikzf2, Ikzf4, and Foxp3. Next, we assessed gene expression in Th1/Tregs. In agreement with our data (Fig.2,5,6), Th1/Tregs expressed lower levels of immunosuppressive genes, including Tnfrsf4, Tnfrsf9, Tnfrsf18, Icos, Ctla4, and the Treg-lineage transcription factors, Ikzf2, Ikzf4, and Foxp3 (Fig.7A). We also detected low expression of Treg stability-associated genes, including Tigit,29 Nrp1,30 Lilrb4,31 and Ikzf4.32 Th1/Tregs expressed several Th1-lineage genes, including Stat1, Nfatc1, Id2, Irf1, and Ifngr1 (Online Table II). Additionally, many non-immune genes were differentially regulated (Online Table II).

To gain insight into which pathways might distinguish Th1/Tregs from Th1s and Tregs, we performed an Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). The cells were clustered on the genes that make up functional pathways, rather than specific lineage genes. As a result, five major clades with Th1/Treg, Th1, and/or Treg characteristics were identified. These clades were characterized as: 1) Th1/Tregs with adhesion and motility, 2) Th1 with PI3K/AKT and glucocorticoids, 3) Tregs with CTLA4, ICOS, and Estrogen Receptor, 4) an anergic/quiescent group of T cells, and 5) Th1/Tregs with glucocorticoid and RhoGDI involvement. A Venn diagram of clades 1, 2, and 3 was generated to show gene expression overlap among the clades (Fig.7B). To evaluate the pathway predominance among the genes (Fig.7B), we used the IPA Connect feature. We observed a bias of connectivity from Th1/Tregs (clade 1) to Th1 (clade 2), over Tregs (clade 3), suggesting that plastic Th1/Tregs are Th1-like (Fig.7B, bottom). We identified 537 Th1/Treg-enriched genes, 85 Th1/Treg-Th1 shared genes, and an additional 50 common Th1/Treg-Treg genes.

To dissect what pathways may be involved in the development and/or maintenance of Th1/Tregs, a pathway map was generated from the 537 Th1/Tregs enriched genes (Fig.7C). IFNγ, IL2RA, CTLA-4, and CCR7-related pathways are present within Th1/Tregs, suggesting that type 1 interferon, CTLA-4, and IL-2 signaling may induce or sustain Th1/Tregs. IL-7R, Fyn, Ets1, Atf1, Csnk2B, Lef1, and Cops5 were identified as additional pathway nodes, suggesting that Th1/Tregs are transcriptionally active (Ets1/Atf1/Lef1), and that IL-7, IL-2, and TCR signaling may also be involved in the generation of Th1/Tregs.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have demonstrated that Tregs may adapt to environmental cues to undergo plasticity, generate Teffector/Treg hybrid cells, and control inflammation.11-15 However, in un-resolving inflammation, excessive STAT1 activation may result in the formation of cytokine-producing Tregs and T effector-mediated pathology. Several studies have reported that atherosclerosis promotes an imbalance in Treg:Teffector ratios5,33, and affects the functionality of Foxp3+ Tregs.7 However it was unclear how pro-atherosclerotic conditions might impact the ratio of Treg:Teffector cells, and functionality of Tregs. Thus we studied the fate of Tregs in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice. We demonstrated that in persistent atherogenic conditions, a population of IFNγ-producing Tregs that we have termed Th1/Tregs is generated within the atherosclerotic aorta and secondary lymphoid tissues. Building on prior work demonstrating the importance of IFNγ in generating a protective CXCR3+ Treg response,11-13 we hypothesized that atherosclerosis might induce CXCR3+ Tregs to counter-balance atherogenesis. However, we observed that atheroprotective CXCR3+ Tregs were reduced in favor of IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs in aged Apoe−/− mice. Moreover these Th1/Tregs consistently expressed reduced levels of immunosuppressive GITR and CD25, but elevated Tbet, IFNγR, and CCR5 expression. Together, these observations suggest that CXCR3+ Tregs and IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs are functionally distinct populations, and that atherosclerosis can skew Tregs from a protective CXCR3+ Treg response to a dysfunctional Th1/Treg response.

There may be several ways of generating Th1/Tregs in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice. IFNγ-IFNγR-STAT1 signaling in Tregs is required for the generation of protective CXCR3+ Tregs. However aberrant STAT1 signaling in Tregs can yield dysfunctional Tregs and IFNγ+ Tregs in graft versus host disease, lethal infection, and in Socs2 or mir146a-deficient mice.16-18 Thus an unbalanced atherogenic Th1 response might result in aberrant IFNγ/IL-27-mediated STAT1 signaling in arterial Tregs, thereby generating a pool of non-suppressive IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs in a STAT1 and Tbet-dependent manner. In support of this notion, we have demonstrated here that Tregs may convert to IFNγ-producing Th1/Tregs in response to the pro-Th1 cytokines IL-12, IL-27, and IFNγ, in vitro. Also in agreement with published data,17 miR-146a-deficient Tregs were comparatively sensitive to IL-12, IL-27 and IFNγ stimulation in vitro, indicating that these cytokines play an important role in Treg plasticity. Furthermore, as IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs accumulate in Apoe−/− but not C57Bl6 aortas with age (unpublished observations), Treg plasticity in atherosclerosis is likely driven by inflammation over time. Additionally, persistent IFNγ/IL-27/STAT1 signaling might down-regulate Ikzf2 (Helios) and Ikzf4 (Eos) expression in Tregs, deregulating Th1 genes. In support of this notion our scRNA-seq results suggest that Th1/Tregs down-regulate Ikzf2 and Ikzf4 (Eos), and Eos was recently shown to restrain IL-17A production in plastic Tregs.

To study the origins and functions of Th1/Tregs in atherosclerosis, we used two complimentary adoptive transfer approaches to determine whether Th1/Tregs arise from plastic Tregs or flexible naïve or effector T cells in Apoe−/− mice. In both experiments, 20-50% of donor Tregs gave rise to Th1/Tregs in Apoe−/− mice, while Teff/naive cells did not. Importantly, analogous adoptive transfers to non-atherosclerotic C57Bl6 recipients failed to yield Th1/Tregs, demonstrating that Treg plasticity is driven by inflammation in atherosclerosis. Additionally as Foxp3-labile exTregs have been described to be pathogenic, we determined whether atherosclerosis might generate exTregs. The entire donor Treg population maintained Foxp3YFP-cre expression in all of the Apoe−/− tissues examined; demonstrating that atherosclerosis supports Treg plasticity, but does not affect Treg stability within 2 weeks. It would be important to determine in future studies whether Th1/Tregs may revert to a Treg phenotype during atheroregression, as it is unclear how the resolution of arterial inflammation might affect arterial T cells.

In this study, we assessed whether plastic Th1/Tregs are still functional Tregs. While we did not observe any differences in the functionality of Apoe−/− or C57Bl6 IFNγ− Tregs, Th1/Tregs were comparatively non-suppressive in vitro. Recent data has demonstrated that Tregs may suppress inflammation through a host of different cell-contact dependent and cell-contact independent mechanisms.34,35 As a part of their cell-contact independent suppressive repertoire, Tregs are known to secrete IL-10, TGFβ, IL-35, immunosuppressive purines, and metabolically compete for growth cytokines and metabolites. As part of their cell-contact-dependent suppressive repertoire, Tregs may block DC maturation and self-antigen presentation via negative co-stimulatory molecules, including at least CTLA4, GITR, PD-1, LAG3, Nrp1, and TIGIT. Many of these genes have been already linked with atheroprotective phenotypes, via global knockouts and cellular studies.36-40 In our study, Th1/Tregs express low levels of known immunosuppressive co-stimulatory molecules including TIGIT, CTLA4, and GITR (Tnfrsf18), lower levels of the metabolic competitor genes Il2ra (CD25) and Folr4 (FR4), and do not appreciably express IL-10 (Fig.3 and 7), suggesting that Th1/Tregs are defective in suppressing inflammation during atherosclerosis in several ways, including cell-contact dependent and cell-contact independent pathways.

While IFNγ is one of the key pro-inflammatory cytokines upregulated in Th1/Tregs, the functional significance of IFNγ production by Th1/Tregs remains to be investigated. Based on our study, Th1/Tregs express slightly less IFNγ than bona fide Th1 cells (Fig.1). However despite producing IFNγ, Th1/Tregs do not accelerate the rate of atherogenesis, as en face lesion volumes were equivalent between Mir146a−/− Treg Apoe−/− and vehicle control Apoe−/− recipients, suggesting that Th1/Tregs are simply unable to adequately suppress atherogenic Th1 responses, rather than actively causing inflammation.

To further examine Treg suppression activity in vivo, we used plasticity-prone miR146a-deficient Tregs to investigate the role of Treg plasticity in atherogenesis. Adoptively transferred miR146a−/− Tregs converted more readily into Th1/Tregs, and permitted additional atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− recipient mice. Together, our results demonstrate that atherosclerosis does not non-specifically affect the functionality of all Tregs, which are unlikely to all be associated with atherosclerosis. Instead, our data suggests that atherosclerosis supports the conversion of an atherosclerosis-responsive Treg subset to non-suppressive Th1/Tregs; thereby permitting arterial inflammation. Importantly, plasticity is widely observed in various human diseases that are characterized by low grade chronic inflammation and autoimmune responses.41 Human Tregs expressing IFNγ are found in the conditions of type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis or juvenile arthritis. While the topic of Treg stability in human atherosclerosis is not yet well studied, evidence suggests that atherosclerosis-prone conditions may impact the plasticity of Th17 cells as IL-17A+IFNg+ T cells are present within human coronary arteries and play a pro-inflammatory role by activating vascular smooth muscle cells.42 Thus, restraining Treg plasticity or reinforcing the Treg phenotype of Th1/Tregs may be therapeutically useful in many chronic inflammatory diseases including atherosclerosis.

To gain further insight into the biology of dysfunctional IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs, we carefully phenotyped these cells by flow cytometry and scRNA-seq experiments. Recent advances in the field of single cell genomics have underscored the power of scRNA-seq in assessing differences amongst individual cells, which can be overlooked in bulk populations and can have striking effects on cellular immunity.20,21,43 We examined the transcriptome of Th1/Tregs, Tregs, and Th1 cells at the single cell level. When we compared Th1/Tregs with Tregs and Th1 cells, we noticed that Th1/Tregs displayed a unique expression and ingenuity pathway pattern (Fig.7). Th1/Tregs were characterized by low expression of immunosuppressive Treg genes, and trended towards higher expression of Th1 genes. While the expression of Foxp-3 by Th1/Tregs was detected using flow cytometry; we detected relatively low expression of Foxp3 in scRNA-seq experiments likely due to effects of “transcriptional bursting”. In addition to the effects of IFNγ, IL-27, Tbet, and STAT1 on Treg plasticity, Tigit,29 Nrp1,30 Lilrb4,31 Ikzf432 and Ikzf244 have recently been identified as Treg stability and functionality-associated genes. Our results here further implicate these genes in atherosclerosis-driven Treg plasticity. The transcriptional co-repressor Eos (Ikzf4) was demonstrated to be labile in a subset of re-programmable Tregs.32 Similarly, Helios was recently shown to be absent and associated with a methylated TSDR region within circulating IFNγ+Foxp3+ Tregs recovered from type-1 diabetic patients.44 Our results suggest that IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs modulate Eos and Helios levels, and that reduced transcriptional co-repression might support the generation of Th1/Tregs during atherogenesis.

Using IPA to determine the cellular pathways that may be active within Th1/Tregs, Tregs, and Th1 cells, we detected common genes between Th1/Tregs-Tregs (50), and Th1/Tregs-Th1 cells (85), and a cohort of Th1/Treg-enriched genes (537). Examination of Th1/Treg-prevalent genes revealed potential roles for IFNγ, CD25, CTLA4, CCR7, IL-7R, Fyn, Ets1, Atf1, Csnk2b, Lef1, CD247, CD81, and Cops5. Interestingly, as Ets1, Atf1, Cops5, and Lef1 are transcription factors linked to IFNγ expression, Th1/Tregs are likely transcriptionally active. Additionally, Csnk2b encodes the constitutively active casein kinase II, which helps Tregs control allergic Th2 responses,31 and Csnk2b is a key regulator of Lilrb4 in Tregs.31 As Th1/Tregs displayed low expression of Lilrb4 and higher expression of Csnk2b, our data suggests that Csnk2b may play a role in Treg plasticity. Altogether, our scRNA-seq IPA-based approach highlights potentially important, distinguishing pathways in Th1/Tregs that may be applicable to other Th1-driven immune-pathologies.

Thus, the results here demonstrate that atherosclerosis promotes Treg plasticity to form a dysfunctional subset of IFNγ+ Th1/Tregs, which fails to adequately suppress arterial inflammation and atherogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

T regulatory cells (Tregs) are immunosuppressive cells that can become less effective during persistent atherogenesis.

Tregs may undergo limited plasticity in Th1-dependent inflammatory conditions, assuming aspects of Th1 cells.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Atherosclerosis supports Treg plasticity, resulting in the generation of IFNg-producing Tregs (termed “Th1/Tregs”).

Th1/Tregs display a mixed Th1 and Treg phenotype and are majorly characterized as Foxp3+Tbet+CXCR3lowCCR5+GITRlowCD25lowCD73highPD-1highCD119lowIFNg+ T cells.

Th1/Tregs express low to negligible levels of several core Treg genes, including Il10, Tigit, Ctla4, Icos, Ikzf2, and Ikzf4.

Th1/Tregs fail to suppress T cell responses in vitro and highly plastic Mir146a−/− Tregs fail to reduce atherogenesis in Apoe−/− recipient mice.

Tregs are known to be immunosuppressive cells in atherosclerosis; however, they become less effective in persistent pro-atherosclerotic conditions via unclear mechanisms. Here, we demonstrate that in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice, some Tregs may undergo partial plasticity to generate a unique Th1-like Treg phenotype (“Th1/Tregs”), characterized by low expression of immunosuppressive genes (e.g. Il10, Tigit, Ctla4, Icos) and expression of pro-inflammatory Th1-related genes (e.g. IFNγ, Tbet, CCR5). Th1/Tregs fail to adequately suppress T cell responses in vitro and in Apoe−/− recipient mice, suggesting that atherosclerosis-driven inflammation may reduce Treg effectiveness in part through Treg plasticity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank John Lynch and Pedja Sekaric (Fluidigm Inc) for their technical assistance creating the single T cell libraries. We also thank Jenhan Tao, Christopher Glass, Kristen Jepsen, and the UCSD Institute of Genomic Medicine Genomics Center for their assistance and expert technical advice on the RNA sequencing and data analysis.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the following grants: NHLBI HL107522 (to E.V. Galkina) and AHA Predoctoral Fellowship grant 11PRE7520041 (to M.J. Butcher).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Treg

T regulatory cells

- Teff/N

CD4+Foxp3− Teffector cells and Naïve T cells

- IFNγ

Interferon-gamma

- Foxp3

Forkhead box P3

- Tbet

T-box 21

- PLN

Peripheral Lymph Nodes

- PALN

Peri-aortic Lymph Nodes

- MLN

Mesenteric Lymph Nodes

- GITR

Glucacortacoid-induced TNFR-related protein

- PD-1

Programmed Death-1

- Mir146a

MicroRNA 146a

- ICS

Intracellular cytokine staining

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- GO

Gene ontology

- scRNA-seq

Single cell RNA sequencing

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Libby P, Lichtman AH, Hansson GK. Immune Effector Mechanisms Implicated in Atherosclerosis: From Mice to Humans. Immunity. 2013;38:1092–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galkina E, Ley K. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis (*) Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:165–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ait-Oufella H, Salomon BL, Potteaux S, et al. Natural regulatory T cells control the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:178–80. doi: 10.1038/nm1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klingenberg R, Gerdes N, Badeau RM, et al. Depletion of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells promotes hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1323–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI63891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng X, Yu X, Ding YJ, Fu QQ, Xie JJ, Tang TT, Yao R, Chen Y, Liao YH. The Th17/Treg imbalance in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2008;127:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Boer OJ, van der Meer JJ, Teeling P, van der Loos CM, van der Wal AC. Low numbers of FOXP3 positive regulatory T cells are present in all developmental stages of human atherosclerotic lesions. PLoS One. 2007;2:e779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maganto-Garcia E, Tarrio ML, Grabie N, Bu DX, Lichtman AH. Dynamic changes in regulatory T cells are linked to levels of diet-induced hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2011;124:185–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.006411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakaguchi S, Vignali DA, Rudensky AY, Niec RE, Waldmann H. The plasticity and stability of regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:461–7. doi: 10.1038/nri3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawant DV, Vignali DA. Once a Treg, always a Treg? Immunol Rev. 2014;259:173–91. doi: 10.1111/imr.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Stolley JM, Campbell DJ. Regulatory T-cell homeostasis: steady-state maintenance and modulation during inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:40–59. doi: 10.1111/imr.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall AO, Beiting DP, Tato C, et al. The cytokines interleukin 27 and interferon-? promote distinct Treg cell populations required to limit infection-induced pathology. Immunity. 2012;37:511–23. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch MA, Tucker-Heard G, Perdue NR, Killebrew JR, Urdahl KB, Campbell DJ. The transcription factor T-bet controls regulatory T cell homeostasis and function during type 1 inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:595–602. doi: 10.1038/ni.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch MA, Thomas KR, Perdue NR, Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Campbell DJ. T-bet(+) Treg cells undergo abortive Th1 cell differentiation due to impaired expression of IL-12 receptor ß2. Immunity. 2012;37:501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voo KS, Wang YH, Santon FR, Boggiano C, Wang YH, Arima K, Bover L, Hanabuchi S, Khalili J, Marinova E, Zheng B, Littman DR, Liu YJ. Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng Y, Chaudhry A, Kas A, deRoos P, Kim JM, Chu TT, Corcoran L, Treuting P, Klein U, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koenecke C, Lee CW, Thamm K, Föhse L, Schafferus M, Mittrücker HW, Floess S, Huehn J, Ganser A, Förster R, Prinz I. IFN-g production by allogeneic Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is essential for preventing experimental graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2012;189:2890–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu LF, Boldin MP, Chaudhry A, Lin LL, Taganov KD, Hanada T, Yoshimura A, Baltimore D, Rudensky AY. Function of miR-146a in controlling Treg cell-mediated regulation of Th1 responses. Cell. 2010;142:914–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oldenhove G, Bouladoux N, Wohlfert EA, et al. Decrease of Foxp3+ Treg cell number and acquisition of effector cell phenotype during lethal infection. Immunity. 2009;31:772–86. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson LJ, Ansel KM. MicroRNA regulation of lymphocyte tolerance and autoimmunity. J.Clin.Invest. 2015;125:2242–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI78090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahata B, Zhang X, Kolodziejczyk AA, Proserpio V, Haim-Vilmovsky L, Taylor AE, Hebenstreit D, Dingler FA, Moignard V, Göttgens B, Arlt W, McKenzie AN, Teichmann SA. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals T helper cells synthesizing steroids de novo to contribute to immune homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1130–42. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shalek AK, Satija R, Shuga J, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic paracrine control of cellular variation. Nature. 2014;510:363–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butcher MJ, Herre M, Ley K, Galkina E. Flow cytometry analysis of immune cells within murine aortas. J Vis Exp. 2011;53:ii, 2848. doi: 10.3791/2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butcher MJ, Gjurich BN, Phillips T, Galkina EV. The IL-17A/IL-17RA axis plays a proatherogenic role via the regulation of aortic myeloid cell recruitment. Circ Res. 2012;110:675–87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foks AC, Lichtman AH, Kuiper J. Treating atherosclerosis with regulatory T cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:280–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyao T, Floess S, Setoguchi R, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Waldmann H, Huehn J, Hoi S. Plasticity of Foxp3(+) T cells reflects promiscuous Foxp3 expression in conventional T cells but not reprogramming of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:262–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollen AA, Nowakowski TJ, Shuga J, et al. Low-coverage single-cell mRNA sequencing reveals cellular heterogeneity and activated signaling pathways in developing cerebral cortex. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1053–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu AR, Neff NF, Kalisky T, Dalerba P, Treutlein B, Rothenberg ME, Mburu FM, Mantalas GL, Sim S, Clarke MF, Quake SR. Quantitative assessment of single-cell RNA-sequencing methods. Nat Methods. 2014;11:41–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai L, Dalal CK, Elowitz MB. Frequency-modulated nuclear localization bursts coordinate gene regulation. Nature. 2008;455:485–90. doi: 10.1038/nature07292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joller N, Lozano E, Burkett PR, et al. Treg cells expressing the coinhibitory molecule TIGIT selectively inhibit proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cell responses. Immunity. 2014;40:569–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delgoffe GM, Woo SR, Turnis ME, Gravano DM, Guy C, Overacre AE, Bettini ML, Vogel P, Finkelstein D, Bonnevier J, Workman CJ, Vignali DA. Stability and function of regulatory T cells is maintained by a neuropilin-1-semaphorin-4a axis. Nature. 2013;501:252–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulges A, Klein M, Reuter S, et al. Protein kinase CK2 enables regulatory T cells to suppress excessive TH2 responses in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:267–75. doi: 10.1038/ni.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma MD, Huang L, Choi JH, Lee EJ, Wilson JM, Lemos H, Pan F, Blazar BR, Pardoll DM, Mellor AL, Shi H, Munn DH. An inherently bifunctional subset of Foxp3+ T helper cells is controlled by the transcription factor eos. Immunity. 2013;38:998–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen Y, Yuan Z, Yin A, Liu Y, Xiao Y, Wu Y, Wang L, Liang X, Zhao Y, Tian Y, Liu W, Chen T, Kishimoto C. Antiatherogenic effect of pioglitazone on uremic apolipoprotein E knockout mice by modulation of the balance of regulatory and effector T cells. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakaguchi S, Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T. Regulatory T cells: how do they suppress immune responses? Int Immunol. 2009;21:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandiyan P, Zhu J. Origin and functions of pro-inflammatory cytokine producing Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Cytokine. 2015;76:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bu DX, Tarrio M, Maganto-Garcia E, Stavrakis G, Tajima G, Lederer J, Jarolim P, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Lichtman AH. Impairment of the programmed cell death-1 pathway increases atherosclerotic lesion development and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1100–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foks AC, Frodermann V, ter Borg M, Habets KL, Bot I, Zhao Y, van Eck M, van Berkel TJ, Kuiper J, van Puijvelde GH. Differential effects of regulatory T cells on the initiation and regression of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;18:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gotsman I, Grabie N, Gupta R, Dacosta R, MacConmara M, Lederer J, Sukhova G, Witztum JL, Sharpe AH, Lichtman AH. Impaired regulatory T-cell response and enhanced atherosclerosis in the absence of inducible costimulatory molecule. Circulation. 2006;114:2047–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.633263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lahoute C, Herbin O, Mallat Z, Tedgui A. Adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis: mechanisms and future therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:348–58. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng X, Yang J, Dong M, Zhang K, Tu E, Gao Q, Chen W, Zhang C, Zhang Y. Regulatory T cells in cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016;13:167–79. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DuPage M, Bluestone JA. Harnessing the plasticity of CD4(+) T cells to treat immune-mediated disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:149–63. doi: 10.1038/nri.2015.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eid RE, Rao DA, Zhou J, Lo SF, Ranjbaran H, Gallo A, Sokol SI, Pfau S, Pober JS, Tellides G. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma are produced concomitantly by human coronary artery-infiltrating T cells and act synergistically on vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2009;119:1424–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.827618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shalek AK, Satija R, Adiconis X, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals bimodality in expression and splicing in immune cells. Nature. 2013;498:236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McClymont SA, Putnam AL, Lee MR, Esensten JH, Liu W, Hulme MA, Hoffmüller U, Baron U, Olek S, Bluestone JA, Brusko TM. Plasticity of human regulatory T cells in healthy subjects and patients with type 1 diabetes. J Immunol. 2011;186:3918–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.