Abstract

Scope and Significance: Reconstruction of traumatic injuries requiring tissue transfer begins with aggressive resuscitation and stabilization. Systematic advances in acute casualty care at the point of injury have improved survival and allowed for increasingly complex treatment before definitive reconstruction at tertiary medical facilities outside the combat zone. As a result, the complexity of the limb salvage algorithm has increased over 14 years of combat activities in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Problem: Severe poly-extremity trauma in combat casualties has led to a large number of extremity salvage cases. Advanced reconstructive techniques coupled with regenerative medicine applications have played a critical role in the restoration, recovery, and rehabilitation of functional limb salvage.

Translational Relevance: The past 14 years of war trauma have increased our understanding of tissue transfer for extremity reconstruction in the treatment of combat casualties. Injury patterns, flap choice, and reconstruction timing are critical variables to consider for optimal outcomes.

Clinical Relevance: Subacute reconstruction with specifically chosen flap tissue and donor site location based on individual injuries result in successful tissue transfer, even in critically injured patients. These considerations can be combined with regenerative therapies to optimize massive wound coverage and limb salvage form and function in previously active patients.

Summary: Traditional soft tissue reconstruction is integral in the treatment of war extremity trauma. Pedicle and free flaps are a critically important part of the reconstructive ladder for salvaging extreme extremity injuries that are seen as a result of the current practice of war.

Keywords: : soft tissue injury, extremity trauma, tissue transfer, flap coverage, extremity reconstruction, microsurgery

Ian L. Valerio, MD, MS, MBA, FACS

Scope and Significance

War is often associated with new discoveries in medicine, significantly impacting our understanding of the body and the impact of the trauma of war. Over the past century, reconstructive surgeons such as Sir Harold Gillies, Varaztad Kazanjian, Archibald McIndoe, Bradford Cannon, James Barret Brown, and Sterling Bunnell used these discoveries to develop new methods to repair disfiguring wounds, including craniofacial defects, hand, and extremity injuries. During World War II, the increased use of antibiotics significantly decreased trauma-related deaths secondary to infection. In Korea and Vietnam, tremendous improvements were seen in extremity salvage, as advances in vascular surgery helped decrease amputation rates. Recently, in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom, balanced resuscitation of red blood cells, plasma, and platelets; prompt and frequent application of tourniquets; and the deployment of forward surgical teams in combination with the rapid casualty evacuation system have resulted in more than 90% of soldiers injured on the battlefield, surviving to undergo definitive treatment at tertiary medical facilities.1 Improved survival in the setting of rising injury severity has led to increased complexity of limb salvage in war-related trauma patients.

The Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) was a multicenter, prospective observational study that was used to develop objective data to help guide the amputation versus limb salvage decision in civilian trauma. LEAP followed 601 patients over 44 months at eight Level I trauma centers.2 The results of this project provided many helpful answers, including: that injury scores were not predictive of amputation, that time to coverage or type of flap had no association with reconstruction outcome, that limb salvage patients were more likely to undergo secondary hospitalization or have complications, and that there was no difference in sickness impact profiles at 2 years between patients who underwent amputation and those who underwent limb salvage.3 The overall late amputation or failed limb salvage rate in the study was 3.9%.2

War trauma is significantly different than civilian trauma. Battlefield trauma causes composite injuries involving bone, blood vessels, nerves, and extensive soft tissue injuries that pose a daunting challenge to surgeons. War wounds are complicated by a large zone of injury with extensive microvascular compromise, wound contamination with soil and vegetation, and delayed extrication to the United States where definitive care and reconstruction are typically performed.4 Godina recommended early coverage of large wounds with vascularized tissue, which has largely been adopted5; however, early definitive closure of large wounds is usually not possible in war patients given the aforementioned wound issues and the need for rapid evacuation of casualties outside the combat zone. Further delay often results, as reconstructive options are evaluated by surgeons outside of the deployed environment who attempt to provide the best functional outcome once concomitant critical injuries are addressed and stabilized.

The classic ladder of soft tissue reconstruction utilized for civilian patients emphasizes using the simplest coverage technique while ensuring the optimal overall outcome (i.e., primary closure before skin graft, skin graft before tissue transfer, pedicle flaps before free flaps). Varying studies have been published comparing local versus free flaps for coverage in limb reconstruction.6 Tintle et al. recommend that when adequate local tissue is available, use of the traditional ladder of reconstruction results in higher limb salvage success rates (Fig. 1).7 Similarly, Burns et al. found a lower amputation and reoperation rate in patients treated with rotational coverage compared with free tissue transfer in the same type of patients.8 However, local tissue has become less available, as explosive munitions have become the main mechanism of war-related injury, causing larger zones of injury. Often, the entirety of both lower extremities is damaged by the sequela of direct blast injury and the subsequent projectiles and pressure wave to the tissue. To address this, military reconstructive teams have adopted a hybrid ladder of reconstruction, which combines local and free tissue transfers with regenerative medicine applications to provide optimized wound care in these blast-related reconstructions.

Figure 1.

(a) Left hand injury before flap coverage. (b) Same left hand injury status post-coverage with a first dorsal metacarpal artery flap. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Traditionally, muscle flaps were preferred over fasciocutaneous flaps in trauma, because both in vitro and in vivo studies indicated that muscle flaps protected against infection and better conformed to complex defects, eliminating dead space dead space (Fig. 2). Decreased dead space resulted in fewer hematoma/seroma complications and a better aesthetic outcome. However, this research has not translated into measureable clinical outcome improvement, with more recent studies showing fasciocutaneous flaps illustrating the same benefits.8–11 In our patients, many of whom are multi-limb amputees, muscle flaps are often not a feasible option in the desire to spare core muscles for rehabilitation purposes (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

(a) Left upper extremity composite type injury involving soft tissue deficits (skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle) and fractured humerus. (b) Same left upper extremity composite type injury with coverage of stabilized bone fracture and functional myocutaneous latissimus flap to restore soft tissue and muscle deficits in combination with skin grafting. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Figure 3.

(a) Left upper extremity consisting of segmental median nerve defect and complex soft tissue injuries. (b) Left upper extremity reconstruction after liposculpting for contour improvement and 2 years after definitive coverage with an anterolateral thigh flap, DRT, split-thickness skin grafting, and allograft and autologous nerve grafting showing finger extension functional outcome. (c) Same extremity injury after reconstruction showing flexion functional outcome. (d) Same extremity injury after reconstruction showing elbow function. DRT, dermal regenerate template. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

Treatment of war trauma has led to significant experience in the use of tissue transfer in severely ill patients in whom flap procedures might not otherwise be pursued. We have performed successful flap transfer in patients with persistent infection, proximal vascular injury, thrombocytosis or venous thromboembolic events, and with the need for massive transfusion. The majority of our patients are young, healthy, and previously very active, prompting us to pursue limb salvage even in the face of the factors mentioned earlier. Thus, our center has developed an algorithm for extremity injuries to both decrease complications and improve success rate for war-related trauma. This article will outline the evolving treatment strategy for complex extremity war injury, specifically blast injuries, with a focus on flap procedures and outcomes.

Translational Relevance

More and more war wounded patients are being evaluated for reconstruction, as advances in forward casualty care, a better understanding of blood product transfusion protocols, improved body armor, and rapid transport from war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan have directly contributed to increased survival rates.12–14 With the increase in patients, many techniques such as delayed primary closure, dermal substitutes and/or extracellular matrices, skin grafting and spray skin technology, regenerative medicine techniques, mesenchymal and adipose-derived stem cell therapies, nerve allografts, external tissue expanders, and the use of multiple rotational and/or free tissue transfers separately or in combination have proved effective in treatment of complex extremity injuries (Fig. 4).12–16 Surgeons choose flaps based on wound geometry and the location of vital structures such as blood vessels, nerves, and bone within the wound as well as attempt to maximize the function of the salvaged limb.17–19 Nonmilitary surgeons can apply these findings to the practice of civilian trauma.

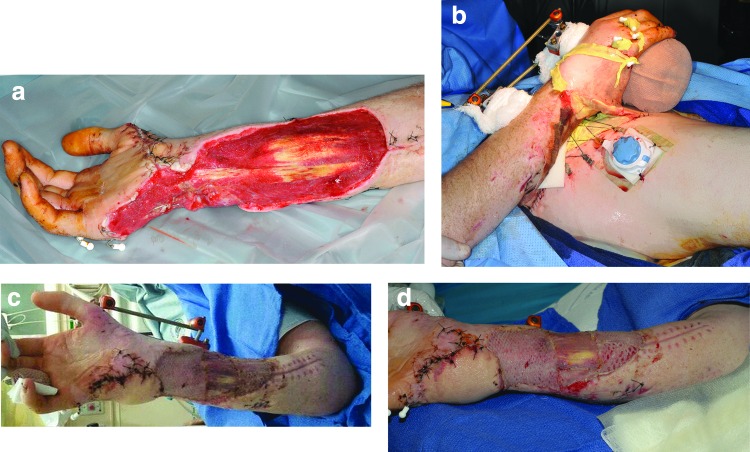

Figure 4.

(a) Right upper extremity defect with exposed carpus and flexor tendons before groin flap and DRT. (b) Right upper extremity injury with pedicle right groin flap coverage before division. (c) Same right upper extremity injury after groin flap division, inset and skin grafting. (d) Second view of same right upper extremity injury after groin flap division, inset and skin grafting. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

A study of the outcomes in our war-wounded patients has led to a better understanding of the optimal timing and reconstruction methods for extremity injuries. Transit time and the need for serial debridement procedures secondary to gross contamination lead to the need to delay definitive reconstruction to the subacute period or greater than 3 days from injury.4 Some patients require greater than a month of stabilization before the wound is appropriate for coverage. Many studies report higher rates of failure, infection, and nonunion when coverage is delayed to the subacute period, whereas our experience demonstrates successful subacute reconstruction.4,17,20 Subacute flap reconstruction at our facility has resulted in flap failure rates less than 10%.17,21–23 These results are not completely without precedent; previous literature has also reported acceptable failure and infection rates for subacute wound coverage.3,24,25 Higgins et al. reported that timing of coverage greater than 3 days, or outside Godina's window, had no effect on infection rates.3 Though we try to minimize the time to reconstruction, definitive flap coverage in a clean field in an otherwise stable patient is paramount to achieving successful tissue transfer after explosive injury. In the past 14 years, we have seen a significant decrease in number of days to flap coverage, 27 to 24 days (p < 0.05); however, nearly all flaps are still performed after 3 days.26

Recently, we have seen a shift toward increased injuries from dismounted (i.e., soldiers patrolling on foot), high-energy explosive injuries. This pattern commonly presents with bilateral lower extremity traumatic amputations, significant upper extremity bony and soft tissue injuries, perineal injuries, traumatic brain injury, and minimal torso involvement. The explosion inoculates the wound with soil, vegetation, and the bacteria and fungus therein. Local tissue is either affected or not present at all, leaving free tissue transfer as the only viable option. Varying studies have been published comparing pedicle versus free flaps in limb reconstruction.17,22 In the early war data, reconstructive surgeons recommended using local tissue over microvascular procedures when possible, citing higher success rates and decreased infection, reoperation, and amputations.7,8 Despite these studies, our group has observed an increased use of free tissue transfer, from 14% in 2004 to 74% in 2011 (p < 0.05).26 As previously stated, free tissue can be harvested from outside the zone of injury, which is often plagued by microvascular injury, muscle necrosis, and infection. Free flaps can be used to cover large wounds with composite defects such as bone or nerve segmental defects. Vascular conduits can even be incorporated into the tissue to create a flow through flaps for arterial reconstruction to maintain distal perfusion. Despite the increased case complexity, our free flap versus pedicle flap success rates were similar between 2003 and 2012: 91.3% versus 89.2%, respectively (p > 0.05) (Figs. 5 and 6).

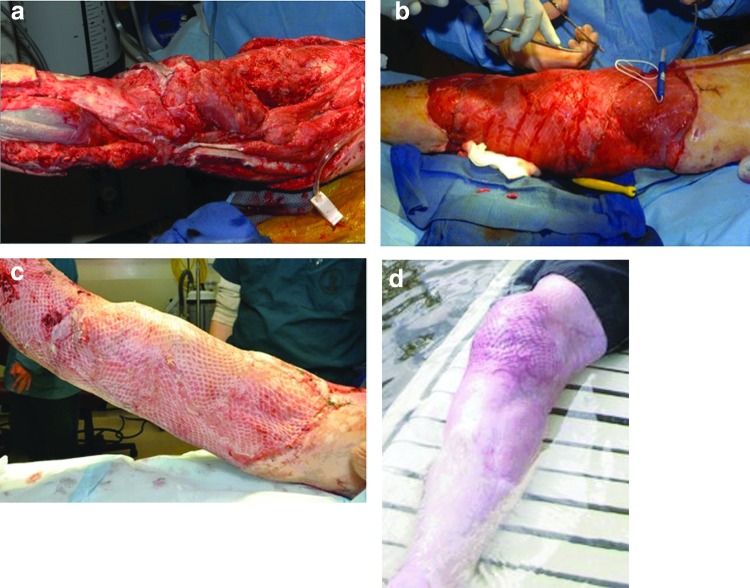

Figure 5.

(a) Right lower extremity blast trauma with soft tissue and orthopedic injuries. (b) Right lower extremity injury status post-coverage with free microvascular latissimus flap transfer. (c) Same right lower extremity reconstruction after latissimus flap coverage and split-thickness skin grafting greater than 1,200 cm2. (d) Same right lower extremity 3 years post-definitive reconstruction. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

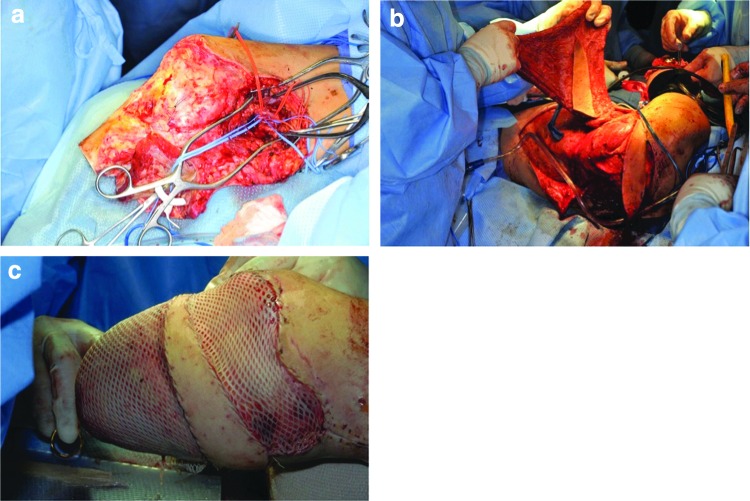

Figure 6.

(a) Right lower extremity residual limb below knee amputation before salvage with free latissimus flap. (b) Same right lower extremity BKA salvage case showcasing myocutaneous latissimus flap harvest. (c) Same right lower extremity BKA salvage after inset of free latissimus flap and skin grafting. BKA, below the knee amputation. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/wound

In response to the increase in free flaps, we sought to determine the best types of flaps for coverage of these injuries. Vascularity, cellularity, and immunologic properties contribute to wound and fracture healing for extremity reconstruction and can be impacted by the type of flap chosen. Selection of flap harvest location and type of tissue is essential in these patients with limited donor sites and high donor site morbidity. Despite a higher vascular density in fasciocutaneous flaps, muscle flaps display a more rapid rate of wound and fracture healing and also have increased antimicrobial properties according to various reports.9,10,27,28 Muscle flaps have also been shown to promote bone repair secondary to a greater amount of osteogenic mesenchymal stem cells and bone anabolics such as interleukin-6 and fibroblast grow factor-2.29,30 Multiple animal studies have demonstrated the importance of muscle coverage on fracture sites, although tissue transfer has not been directly examined within these studies.9–11,31 Retrospective reviews of patients with open tibia fractures show that muscle flaps can reduce healing time and decrease infection and necrosis rates compared with fasciocutaneous flaps.32,33 This literature has led many to propose that muscle flaps are the preferential choice to cover open fractures.

Despite these studies, fasciocutaneous flaps have gained popularity, as they perform similarly to muscle flaps while providing a more “like” tissue in a number of recent reviews.34–36 Yazar and colleagues reported equal outcomes between muscle and fasciocutaneous flaps in terms of flap survival, postoperative infection, osteomyelitis, primary and overall bone union, and ambulation without crutches. Another advantage of fasciocutaneous flaps in our patients who have suffered multiple amputations is the sparing of core muscles to facilitate earlier rehabilitation. This is especially evident in individuals having above-the-knee amputations or hip disarticulations that can require more than twice the amount of energy expenditure to ambulate on prosthetics.35,37–39 Although the majority of our patients do not return to service, they do go on to lead highly active personal lives and remain important members of the military community. In our series, we found that muscle flaps had a significantly higher failure rate compared with fasciocutaneous flaps (13% vs. 5%, p < 0.05).40 The most common cause of flap failure was total necrosis or flap infection. As a result, fasciocutaneous flaps harvested from areas of the body protected by body armor have become the workhorse of our reconstructive efforts.

Given the severity of war trauma, especially explosive injuries, patients often have concomitant conditions that may affect flap outcomes. We looked at several variables that may contribute to flap failure. One quarter of patients who undergo tissue transfer for extremity reconstruction have a vascular injury proximal to the flap recipient site. The total flap complication rate in patients with proximal vascular injury was 31%; 8% of these flaps failed. These outcomes are similar to the flap complication (28%) and failure (10%) rates in the cohort of patients who did not suffer a concurrent vascular injury (p > 0.05).41 Twenty-six percent of flaps were performed in the setting of a pre- or perioperative venous thromboembolic event. However, we found no difference in flap or limb salvage outcomes in patients with or without a deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.42 Similarly, tranexamic acid (TXA) administration during initial resuscitation or preoperative thrombocytosis did not affect tissue transfer outcomes.43,44 As a result, we feel that tissue transfer can be performed in a number of clinically difficult situations and should remain an option in the limb salvage algorithm.

Clinical Relevance

The past 14 years of war trauma have increased our understanding of the use of tissue transfer for limb salvage in the treatment of high-energy blast injury. Undertaking of cases requiring pedicle or free tissue transfer can be performed safely in the subacute period to stabilize concomitant injuries and to prepare the wound bed. Free flaps are often required, because local tissue is involved in the zone of injury. Fasciocutaneous flaps have a significant role in extremity reconstruction, especially in patients with rehabilitation needs requiring core muscle strength, and they should be considered a first choice when appropriate. Flaps can also be performed in patients with a number of comorbidities that are associated with trauma, and treatment options should be tailored to the individual patient and injury pattern.

Future Directions

War-injured patients differ from patients undergoing civilian trauma in the mechanism of injury, severity, and environment in which they sustain trauma. Therefore, our findings must be applied cautiously to civilian cohorts in whom wounding patterns, psychosocial patient traits, and institutional support may be significantly different. However, certain civilian mass casualty events and terrorist-related events such as the Boston Marathon bombing (2013), the Mumbai, India bombing (2008), the London mass transit bombing (2005), and ongoing conflicts spanning various parts of the globe illustrate the severe damage that explosive trauma can have on human casualties. We hope this work will continue to advance our understanding of war, ballistic, and blast-related trauma reconstruction as well as hopefully stimulate innovative strategies to optimize function and aesthetics in extremity reconstruction for the treatment of both military and civilian patients.

Summary

War trauma causes devastating extremity wounds that often require multiple components of the soft tissue ladder for optimal reconstruction. We have seen this amplified in the setting of high energy explosive trauma that is indicative of the conflicts of the last 15 years. Pedicle and free tissue transfer, as well as, regenerative medicine modalities have a role in treating complex wounds when taking into account each patients' individual wound characteristics and rehabilitation goals. Reconstruction in the subacute period, greater than seven days after injury, allows for patient stabilization and wound bed preparation. Free tissue transfer for extremity salvage offers high success rates in providing tissue outside of the zone of injury while reliably covering vital structures to maintain form and function. Fasciocutaneous flaps are comparable to muscle flaps outcomes with lower donor site morbidity. Successful outcomes are possible in patients with proximal vascular injury, high platelet counts, and previous antifibrinolytic use. These treatment strategies can be applied to civilian trauma for similar results.

Take-Home Messages.

• Devastating complex extremity injuries are common in modern warfare as a result of increased use of blast-related mechanisms.

• All components of the ladder of soft tissue reconstruction and regenerative medicine strategies are used to treat these wounds.

• Subacute reconstruction is usually necessary.

• Free flaps and myocutaneous flaps have become increasing useful in the war wounded.

• Each patient should be evaluated individually in terms of wound characteristics and treatment and rehabilitation goals to develop a specific wound care/limb salvage strategy.

Abbreviation and Acronym

- LEAP

Lower Extremity Assessment Project

Acknowledgments and Funding Sources

The authors thank the Departments of General, Orthopedic, Plastic, and Reconstructive Surgery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for their contributions to this work.

Author Disclosure and Ghostwriting

The authors have no affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this article. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

About the Authors

Jennifer Sabino, MD is a plastic surgery resident at Johns Hopkins University/University of Maryland. She is a board certified general surgeon completing a general surgery residency at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. She is a Major in the United States Army and will serve as a plastic surgeon in the military on completion of her training. Julia C. Slater, MD is a plastic surgery resident at the University of Kansas in Kansas City. She is a board certified general surgeon and has completed a burn and reconstruction fellowship at Johns Hopkins University. Ian L. Valerio, MD, MS, MBA, FACS is the Director of Burn, Wound, and Trauma with appointments in the Departments of Plastic, Orthopedic, and General Surgery at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, and serves as a Commander in the Medical Corps for the Expeditionary Medical Forces - Bethesda and Great Lakes. He is a plastic surgeon who specializes in traumatic, oncologic, craniofacial, burn, wound, and pediatric reconstructive surgery, amputee care, peripheral nerve repair, targeted reinnervation, vascularized composite tissue allotransplantation, and aesthetic surgery. Additionally, he has experience in wounded warrior care and deployment experience as a surgeon who operated in the U.S. NATO affiliated countries, and Afghanistan.

References

- 1.Holcomb JB, Stansbury LG, Champion HR, Wade C, Bellamy RF. Understanding combat casualty care statistics. J Trauma 2006;60:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Kellam JF, et al. An analysis of outcomes of reconstruction or amputation of leg threatening injuries. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1924–1931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgins TF, Klatt JB, Beals TC. Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP)—the best available evidence on limb-threatening lower extremity trauma. Orthop Clin North Am 2010;41:233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CK, Obremskey W, Hsu JR, et al. Prevention of infections associated with combat-related extremity injuries. J Trauma 2011;71:S235–S257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godina M. Early microsurgical reconstruction of complex trauma of extremities. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;78:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollak AN, McCarthy ML, Burgess AR. Short-term wound complications after application of flaps for coverage of traumatic soft-tissue defects about the tibia. The Lower Extremity Assessment Project (LEAP) Study Group. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82-A:1681–1691 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tintle SM, Gwinn DE, Andersen RC, Kumar AR. Soft tissue coverage of combat wounds. J Surg Orthop Adv 2010;19:29–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns TC, Stinner DJ, Possley DR, et al. Skeletal Trauma Research Consortium (STReC). Does the zone of injury in combat-related Type III open tibia fractures preclude the use of local soft tissue coverage? J Orthop Trauma 2010;24:697–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harry LE, Sandison A, Paleolog EM, Hansen U, Pearse MF, Nanchahal J. Comparison of the healing of open tibial fractures covered with either muscle or fasciocutaneous tissue in a murine model. J Orthop Res 2009;26:1238–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harry LE, Sandison A, Pearse MF, Paleolog EM, Nanchahal J. Comparison of the vascularity of fasciocutaneous tissue and muscle for coverage of open tibial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:1211–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards RR, McKee MD, Paitich CB, Anderson GI, Bertoia JT. A comparison of the effects of skin coverage and muscle flap coverage on the early strength of union at the site of osteotomy after devascularization of a segment of canine tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991;73:1323–1330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamumadass M, Kagan R, Matsuda T. Early coverage of deep hand burns with groin flaps. J Trauma 1987;27:109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moiemen NS, Vlachou E, Staiano JJ, Thawy Y, Frame JD. Reconstructive surgery with Integra dermal regeneration template: histologic study, clinical evaluation, and current practice. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:160S–174S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karsidag S, Akcal A, Turgut G, Ugurlue K, Bas L. Lower extremity soft tissue reconstruction with free flap based on subscapular artery. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2011;45:100–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray C, Obremskey W, Hsu JR, et al. ; Prevention of Combat-Related Infections Guidelines Panel. Prevention of infections associated with combat-related extremity injuries. J Trauma 2011;71:S235–S257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JE, Rodriguez ED, Bluebond-Langer R, et al. The anterolateral thigh flap is highly effective for reconstruction of complex lower extremity trauma. J Trauma 2007;62:162–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar AR, Grewal NS, Chung TL, Bradley JP. Lessons from operation Iraqi freedom: successful subacute reconstruction of complex lower extremity battle injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;123:218–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heller L, Levin LS. Lower extremity microsurgical reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108:1029–1041; quiz 1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herter F, Ninkovic M. Rational flap selection and timing for coverage of complex upper extremity trauma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2007;60:760–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zouris JM, Walter GJ, Dye J, Galarneau M. Wounding patterns for U.S. Marines and sailors during Operation Iraqi Freedom, major combat phase. Mil Med 2006;171:246–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen-Gunther J, Ellison R, Kuhens C, Roach CJ, Jarrard S. Trends in combat casualty care by forward surgical teams deployed to Afghanistan. Mil Med 2001;176:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar AR. Standard wound coverage techniques for extremity war injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006;14:S62–S65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrd HS, Cierny G, III, Tebbetts JB. The management of open tibial fractures with associated soft tissue loss: external pin fixation with early flap coverage. Plast Reconstr Surg 1981;68:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saint-Cyr M, Gupta A. Indications and selection of free flaps for soft tissue coverage of the upper extremity. Hand Clin 2007;23: 37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khouri RK, Shaw WW. Reconstruction of the lower extremity with microvascular free flaps: a 10-year experience with 304 consecutive cases. J Trauma 1989;29:1086–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valerio I, Sabino J, Mundinger GS, Kumar AK. From battleside to statesdie: the reconstructive journey of our wounded warriors. Ann Plast Surg 2014;72:S38–S45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gosain A, Chang N, Mathes S, Hunt TK, Vasconez L. A study of the relationship between blood flow and bacterial inoculation in musculocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990;86:1152–1162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calderon W, Chang N, Mathes SJ. Comparison of the effect of bacterial inoculation in musculocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1986;77:785–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans CH, Liu FJ, Glatt V, et al. Use of genetically modified muscle and fat grafts to repair defects in bone and cartilage. Eur Cell Mater 2009;18:96–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogt PM, Boorboor P, Vaske B, Topsakal E, Schneider M, Muehlberger T. Significant angiogenic potential is present in the microenvironment of muscle flaps in humans. J Reconstr Microsurg 2005;21:517–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Utvag SE, Grundnes O, Reikeras O. Effects of lesions between bone, periosteum and muscle on fracture healing in rates. Acta Orthop Scand 1998;69:177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Georgiadis GM, Behrens FF, Joyce MJ, Earle AS, Simmons AL. Open tibial fractures with severe soft-tissue loss: limb salvage compared with below-the-knee amputation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:1431–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Small JO, Mollan RA. Management of the soft tissue in open tibial fractures. Br J Plast Surg 1992;45:571–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yazar S, Lin CH, Lin YT, Ulusal AE, Wei FC. Outcome comparison between free muscle and free fasciocutaneous flaps for reconstruction of distal thir and ankle traumatic open tibial fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:2468–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hallock G. Utilitay of both muscle and fascia flaps in severe lower extremity trauma. J Trauma 2000;48:913–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hallock G. Relative donor-site morbidity of muscle and fascial flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993;92:70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yildirim S, Gideroglu K, Akoz T. Anterolateral thigh flap: ideal free flap choice for lower extremity soft-tissue reconstruction. J Reconstr Microsurg 2003;19:225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hallock GG. Lower extremity muscle perforator flaps for lower extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;114:1123–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francel TJ, Vanderkolk CA, Hoopes JE, Manson PN, Yaremchuk MJ. Microvascular soft-tissue transplantation for reconstruction of acute open tibial fractures: timing of coverage and long-term functional results. Plast Reconstr Surg 1992;89:478–487 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabino J, Polfer E, Tintle S, et al. A decade of conflict: flap coverage options and outcomes in traumatic war-related extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg 2015;135:895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casey K, Sabino J, Jessie E, Martin BD, Valerio I. Flap coverage outcomes following vascular injury and repair: chronicling a decade of severe war-related extremity trauma. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135:301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valerio I, Sabino J, Heckert R, et al. Known preoperative deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolus: to flap or not to flap the severely injured extremity? Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;132:213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valerio IL, Campbell P, Sabino J, et al. TXA in combat casualty care—does it adversely affect extremity reconstruction and flap thrombosis rates? Mil Med 2015;180:24–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sabino J, Fleming M, Potter BK, Valerio I. Platelets and aspirin use as a predictor of flap failure in war-related extremity reconstruction. Presented at 8th Congress of World Society of Reconstructive Microsurgery, Mumbai, India, March22, 2015 [Google Scholar]