Abstract

Context.—

Cardiac hepatopathy and Budd-Chiari syndrome are 2 forms of hepatic venous outflow obstruction with different pathophysiology but overlapping histologic findings, including sinusoidal dilation and centrilobular necrosis.

Objective.—

To determine whether a constellation of morphologic findings could help distinguish between the 2 and could suggest the diagnoses in previously undiagnosed patients.

Design.—

We identified 26 specimens with a diagnosis of cardiac hepatopathy and 23 with a diagnosis of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with trichrome were evaluated for several distinctive histologic findings.

Results.—

Features common to both forms of hepatic outflow obstruction included sinusoidal dilation and portal tract changes of fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and bileductular reaction. Histologic findings significantly more common in cardiac hepatopathy included pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis and fibrosis around the central vein. Only centrilobular hepatocyte dropout/necrosis was significantly more common in Budd-Chiari, regardless of duration.

Conclusions.—

The finding of pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis in cardiac hepatopathy compared with Budd-Chiari is not unexpected, given the chronic nature of most cardiac hepatopathy. Portal tract changes are common in both forms of hepatic outflow obstruction and should not deter one from making the diagnosis of hepatic outflow obstruction. Fibrosis along sinusoids and around the central vein may be suggestive of cardiac hepatopathy in biopsies from patients without a prior diagnosis.

Budd-Chiari syndrome and cardiac (congestive) hepatopathy are the 2 most well-known diagnoses in the category of hepatic venous outflow obstruction. Although the 2 diseases differ in their clinical presentations, etiologies, and points of occlusion along the hepatic outflow tract, they show similar morphologic findings on sampling of patient liver tissue.1

Budd-Chiari syndrome refers to obstruction of the hepatic outflow tract, typically by thrombosis, anywhere from the hepatic venules to the junction of the inferior vena cava and right atrium.2 It occurs in approximately 0.001% of the population and has numerous potential etiologies, including inherited and acquired prothrombotic states, myeloproliferative diseases, and oral contraceptive use.2,3 Patients may present with acute, subacute, or chronic disease. The diagnosis can often be made clinically by radiologic demonstration of outflow obstruction, though patients with obstruction of intrahepatic veins may have normal findings on imaging.3 Pathologic changes in biopsied or explanted livers of patients with Budd-Chiari characteristically include perivenular necrosis, sinusoidal dilation, and occasionally formation of macronodules resembling focal nodular hyperplasia.1,4

In cardiac hepatopathy, right-sided heart failure of any cause prevents proper blood flow into the heart. This leads to a backlog of blood in the venae cavae and ultimately within the liver, causing intrahepatic congestion. This process causes the classic gross appearance of nutmeg liver, and longstanding congestion can lead to extensive fibrosis (termed either cardiac sclerosis or cardiac cirrhosis). The degree of cardiac dysfunction and severity of clinical presentation can vary widely, and as a result, cardiac hepatopathy may not be suspected clinically and therefore could progress undiagnosed.1 Patients under consideration for heart transplant may undergo liver biopsy to assess for the presence and severity of cardiac hepatopathy, as preoperative hepatic disease has been linked to postoperative morbidity.5–7 Biopsy findings include centrilobular and sinusoidal dilation and centrilobular necrosis, depending on the severity of the cardiac disease.2,7–9

A third type of hepatic outflow impairment, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (previously termed veno-occlusive disease), occurs when the hepatic sinusoids or central veins become obstructed. Though originally described in Jamaican children with alkaloid-induced hepatotoxicity, it is most commonly seen in the setting of myeloablative therapy for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. It demonstrates a characteristic histologic pattern, with acute disease typified by marked sinusoidal dilation and congestion, with loss of sinusoidal endothelium, and chronic disease demonstrating central vein occlusion.1 These clinicopathologic findings help distinguish it from Budd-Chiari syndrome and cardiac hepatopathy.

Although Budd-Chiari and cardiac hepatopathy are typically diagnosed clinically, patients with occult disease may undergo liver biopsy for nonspecific findings, such as elevated liver enzymes. Given the overlap in histologic pattern in the 2 conditions, this study aimed to determine whether certain microscopic changes were significantly more common in either, allowing for distinction between their otherwise-similar microscopic appearances and facilitating identification of the diseases in patients without a definitive clinical diagnosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

With appropriate institutional review board approval, we searched the archives of the Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Microbiology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, as well as the personal files of one of the authors, for liver specimens from patients carrying a preoperative or postoperative diagnosis of cardiac hepatopathy or Budd-Chiari syndrome. We did not search for cases of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome, because of its aforementioned characteristic histologic findings and distinctive clinical setting.

In each case identified, representative hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides were reviewed, along with trichrome-stained slides. All tissue sections were examined for presence or absence of the following: sinusoidal dilation, portal bile ductular reaction, centrilobular inflammation, portal inflammation, centrilobular dropout/necrosis, portal fibrosis, fibrosis surrounding the central vein, pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis, red blood cells in the space of Disse, lobular cholestasis (within canaliculi and/or hepatocytes), macrovesicular steatosis (at least 5%), glycogenated hepatocyte nuclei, centrilobular hemorrhage, centrilobular hemosiderin deposition, centrizonal bile ductular reaction, and centrizonal arterioles. The fibrosis-related criteria were assessed on the trichrome-stained slides, and the other criteria were assessed on the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides. When available, patient charts were reviewed for relevant clinical history, and specific laboratory values (total protein, albumin, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate transaminase, and alanine transaminase) reported as close to the tissue sampling as possible were recorded. Hepatic vein wedge pressure was also recorded when available.

Tabulated histologic findings and patient sex were compared using a Fisher exact test on 2 × 2 contingency tables, and the remaining clinical information, including laboratory value data, was compared using an unpaired t test, all in GraphPad Software online (http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs; GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We identified 26 specimens from patients with an established clinical diagnosis of cardiac hepatopathy (all biopsies, all from different patients) and 23 specimens from patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome (15 biopsies and 8 hepatectomies, from 20 patients). Other known hepatologic diagnoses included 1 patient with chronic hepatitis B infection (in the cardiac hepatopathy group), and 1 patient each with Wilson disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis after transplant, biliary atresia after transplant, and overlapping autoimmune hepatitis/primary sclerosing cholangitis after transplant (in the Budd-Chiari group). The Budd-Chiari specimens were stratified into 3 groups, based on length of time between symptom onset and liver sampling: acute disease (2 weeks or shorter, 5 cases), subacute disease (between 2 weeks and 6 months, 10 cases), and chronic disease (6 months or longer, 7 cases). Symptom length was not available for 1 case.

Basic patient demographic information is shown in Table 1. Patients with cardiac hepatopathy were older than those with Budd-Chiari (P = .003). They also had a somewhat higher rate of diabetes (P = .09) and tended to be male, whereas Budd-Chiari patients tended to be female (P = .06). The 2 groups had similar body mass indexes (P = .76). Major clinical diagnoses in the cardiac hepatopathy group included congestive heart failure (n = 7), cardiomyopathy (ischemic [n=3], nonischemic [n=2], not otherwise specified [n=4]), and valve disease (n = 2); none underwent heart transplant prior to liver biopsy. Most cardiac hepatopathy patients (19 of 22; 86%) were biopsied to evaluate for cirrhosis and/or candidacy for heart surgery; the rest (3 of 22; 14%) were biopsied because of elevated liver function tests. In the Budd-Chiari group, 4 patients had polycythemia vera, and 1 patient each had factor V Leiden, lupus anticoagulant, and history of oral contraceptive use. Of 19 Budd-Chiari patients, 10 (53%) underwent liver biopsy or transplant for known disease, 3 (16%) were being followed after liver transplant for unrelated disease, and 6 (32%) were biopsied or transplanted for cirrhosis or liver dysfunction of then-unclear etiology.

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical Findings in Cardiac Hepatopathy (CH) and Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BC)a

| CH (n = 23) | BC (n = 19) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | .003b | ||

| Average | 54 | 40 | |

| Range | 25–78 | 1–61 | |

| Sex, M:F | 17:6 | 8:11 | .06 |

| Diabetes mellitus, No. (%) | 10 (43) | 3 (16) | .09 |

| Body mass index | .76 | ||

| Average | 27.3 | 27.9 | |

| Range | 17.0–41.3 | 16.3–39.6 |

Some cases were excluded because of unavailable clinical data.

Indicates statistical significance (P <.05).

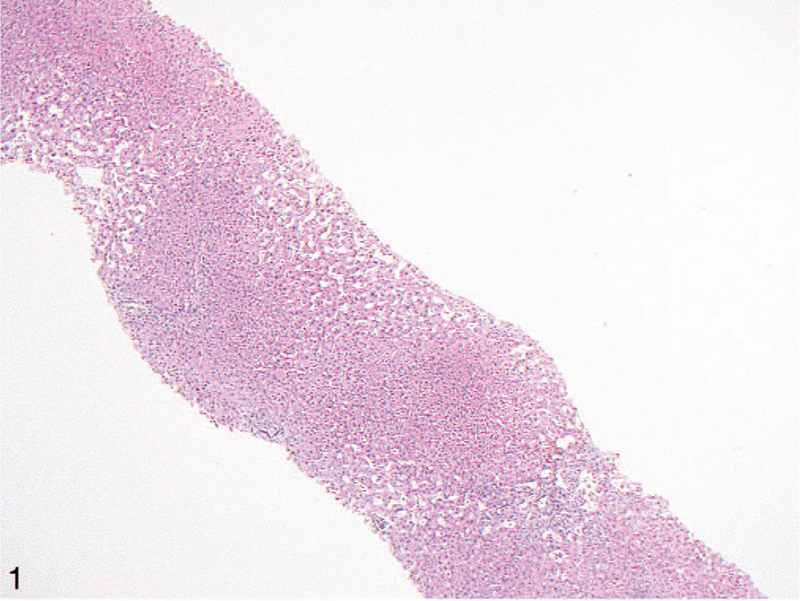

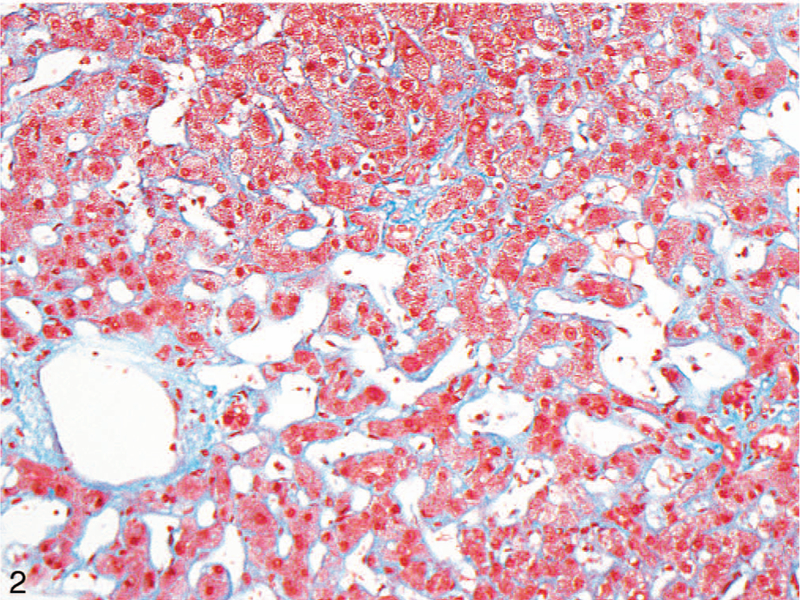

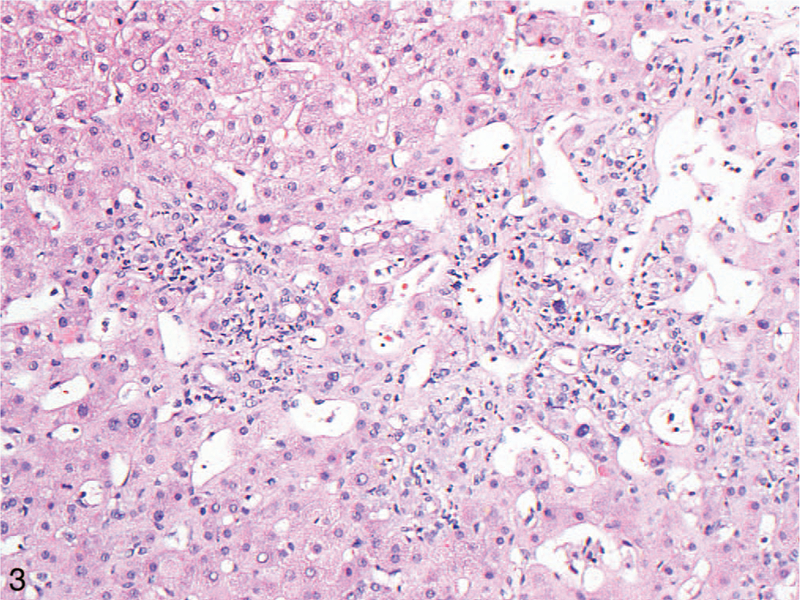

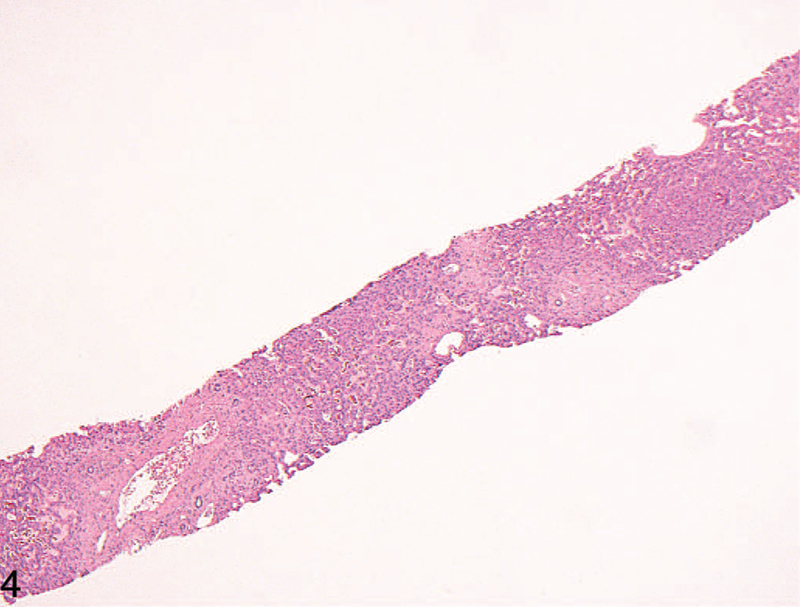

Most histologic findings were seen in a similar proportion of both diagnoses (P ≥ .05; Table 2 and Figure 1). However, 3 findings were significantly more common in cardiac hepatopathy than in Budd-Chiari syndrome: fibrosis surrounding the central vein (92% versus 65%, P = .03), pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis (92% versus 48%, P = .001; Figure 2), and glycogenated nuclei (62% versus 30%, P = .045). Centrilobular inflammation was also somewhat more commonly seen in cardiac hepatopathy (50% versus 30%, P = .25; Figure 3); it was usually mild and frequently contained admixed neutrophils. The reason for this somewhat unusual finding was unclear, and it had no relationship to the presence of macrovesicular steatosis (P = .52), suggesting it was not indicative of steatohepatitis. Only centrilobular dropout/necrosis was significantly more common in Budd-Chiari (35% versus 83%, P = .001; Figures 4 through 6). In both groups, pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis had no relationship with portal inflammation (P = .36), ductular reaction (P > .99), portal fibrosis (P = .30), or steatosis (P = .73).

Table 2.

Comparison of Hepatic Histologic Findings in Cardiac Hepatopathy (CH) and Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BC)

| No. (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| CH (n = 26) | BC (n = 23) | P | |

| Sinusoidal dilation | 25 (96) | 19 (83) | .17 |

| Portal bile ductular reaction | 15 (58) | 16 (70) | .55 |

| Centrilobular inflammation | 13 (50) | 7 (30) | .25 |

| Portal inflammation | 15 (58) | 15 (65) | .77 |

| Centrilobular dropout/necrosis | 9 (35) | 19 (83) | .001a |

| Portal fibrosis | 19 (73) | 18 (78) | .75 |

| Fibrosis around central vein | 24 (92) | 15 (65) | .03a |

| Pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis | 24 (92) | 11 (48) | .001a |

| Red blood cells in space of Disse | 17 (65) | 19 (83) | .21 |

| Cholestasis | 5 (19) | 8 (35) | .34 |

| Steatosis | 4 (15) | 2 (9) | .67 |

| Glycogenated nuclei | 16 (62) | 7 (30) | .045a |

| Centrilobular hemorrhage | 12 (46) | 16 (70) | .15 |

| Centrilobular hemosiderin | 11 (42) | 10 (43) | >.99 |

| Centrilobular bile ductules | 18 (69) | 15 (65) | >.99 |

| Centrilobular arterioles | 10 (38) | 8 (35) | >.99 |

Indicates statistical significance (P < .05).

Figure 1.

Low-power view of a liver biopsy from a patient with cardiac (congestive) hepatopathy. The most striking finding is centrilobular sinusoidal dilation. This is commonly seen in hepatic outflow obstruction and can also be observed in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40).

Figure 2.

Fibrosis along the central vein and sinusoids (highlighted by Masson trichrome stain) were the main findings significantly more common in cardiac hepatopathy than in Budd-Chiari syndrome (original magnification ×200).

Figure 3.

Centrilobular inflammation, including neutrophils, was more commonly seen in the liver in cardiac hepatopathy than in Budd-Chiari syndrome (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200).

Figure 4.

Low-power view of a case of Budd-Chiari syndrome, with prominent centrilobular dropout/necrosis, which was significantly more often present in this condition (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40).

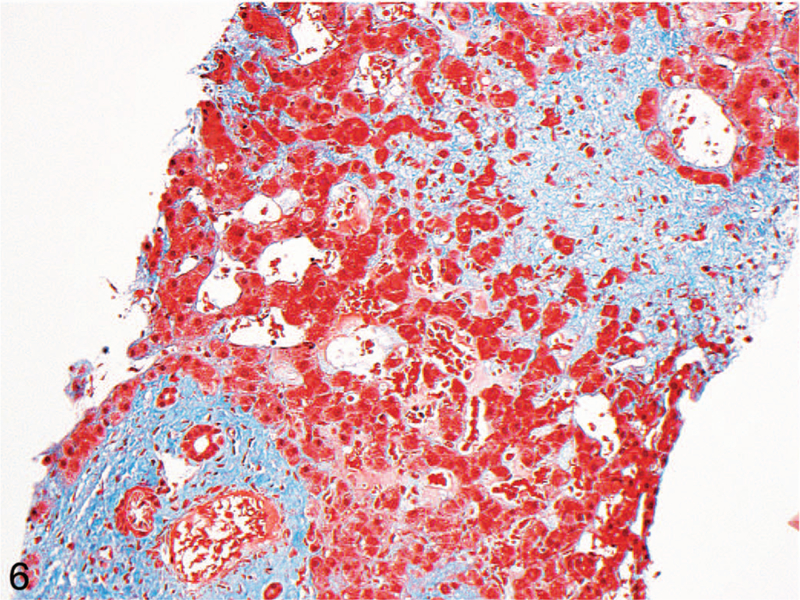

Figure 6.

Masson trichrome stain highlighting the centrilobular dropout (light blue, upper right), compared with mild portal fibrosis in the same biopsy (darker blue, bottom left) (original magnification ×200).

When stratifying the Budd-Chiari patients into 2 groups (acute disease versus subacute or chronic disease), the former group had a lower rate of fibrosis around the central vein (1 of 5 [20%] versus 13 of 17 [76%], P = .04). This significance did not hold when instead stratifying the patients into acute or subacute disease versus chronic disease groups (P > .99). Neither of these duration stratifications demonstrated a significant relationship with centrilobular necrosis, pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis, or portal fibrosis.

When comparing all cardiac hepatopathy cases with only subacute and chronic Budd-Chiari cases (ie, removing the acute cases), sinusoidal fibrosis remained more common in the cardiac hepatopathy group (92% versus 53%, P = .007), but fibrosis around the central vein became equally common in both diagnoses (92% versus 76%, P = .19). Comparing all cardiac hepatopathy cases with only chronic Budd-Chiari cases, sinusoidal fibrosis barely lost its significant increase in the former group (92% versus 57%, P = .05), though the chronic Budd-Chiari group contained only 7 cases for comparison.

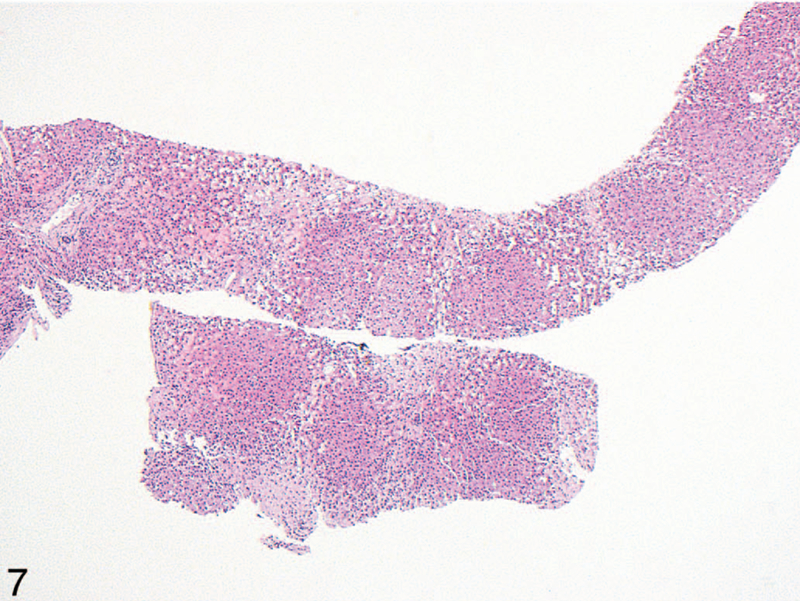

End-stage liver disease was evident in 7 of the cardiac hepatopathy cases (27%) and 8 of the Budd-Chiari cases (35%). Cardiac hepatopathy patients usually demonstrated cardiac sclerosis, where regions of stellate centrizonal fibrosis haphazardly aggregated until dominating the hepatic parenchyma, as opposed to traditional nodular cirrhosis (6 versus 1); in end-stage Budd-Chiari, however, this haphazard pattern was less common than well-formed fibrosis encircling well-defined regenerative nodules (3 versus 5; Figure 7). In 2 of the Budd-Chiari cases, this nodular cirrhosis primarily demonstrated a reversed-lobulation arrangement, with most of the fibrosis spanning from central vein to central vein, with relative sparing of portal tracts.10 However, at least some portal-central septa were present in all cases.

Figure 7.

End-stage liver in a patient with Budd-Chiari syndrome. There is patchy, haphazard fibrosis extending between central veins, without well-defined nodule formation as would be seen in classic cirrhosis. This pattern is more commonly seen in patients with cardiac hepatopathy, where it is termed cardiac cirrhosis or cardiac sclerosis (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40).

There were no significant differences in any analyzed mean laboratory values between the 2 groups of patients (total protein, P = .20; albumin, P = .09; total bilirubin, P = .20; alkaline phosphatase, P = .25; aspartate transaminase, P = .14; alanine transaminase, P = .16). Hepatic vein wedge pressure was only available for 15 of the 46 patients (33%) and was therefore not included in the comparative analysis.

DISCUSSION

The general histomorphologic features of hepatic venous outflow obstruction have been well characterized. Autopsy studies from the 1980s of several hundred patients with cardiac dysfunction9,11 demonstrated that cardiac hepatopathy manifests microscopically as sinusoidal congestion and dilation, centrilobular necrosis, centrilobular inflammation, hepatocyte atrophy, regenerative hyperplasia, and cardiac sclerosis, which was defined by Lefkowitch and Mendez9 as ‘‘fibrous tissue scars involving the walls of central veins (or their lumens) and extending for variable distances into the lobule where they filled the space of Disse and surrounded hepatocytes.’’ Similar findings have been reported in the livers of patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome, namely sinusoidal dilation, centrilobular necrosis, and perivenular fibrosis.4 Additionally, the development of regenerative nodule formation has been reported in both conditions, though it has received more attention in Budd-Chiari.4,9,10,12,13

Particularly in biopsy samples, the most striking histologic finding upon initial microscopic examination of the liver from patients with either condition is typically sinusoidal dilation. Although sinusoidal pathology can be seen in many other conditions,14 prominent dilation often prompts the inclusion of ‘‘outflow obstruction’’ in the differential diagnosis. Particularly if the patient has not been evaluated clinically for Budd-Chiari or cardiac hepatopathy, it can sometimes be difficult to offer a more specific diagnosis. Although such a scenario may not be especially common, other microscopic clues may be of value when it does occur.

The finding of sinusoidal dilation without necrosis, or chronic passive congestion, has been commonly ascribed to heart failure and resultant elevated systemic venous pressure.11,15 The additional presence of centrilobular necrosis, which we found more commonly in Budd-Chiari, suggests ischemia secondary to hepatic hypoxia, which preferentially affects centrilobular hepatocytes first. More exaggerated centrilobular necrosis has been described in situations leading to inadequate portal vein perfusion of the liver, such as shock.11,15 Linking these 2 pathophysiologic processes are the facts that, in Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein perfusion is decreased2 and portal vein occlusion has been reported as a not-uncommon finding.1,4,10,12 Although not absolute, these 2 patterns of liver injury can be considered to correspond to acute (thrombotic) and chronic (congestive) patterns of liver hypoxia.

We observed a multitude of other pathologic findings in our series that were less obviously ascribable to outflow obstruction. Centrilobular inflammation, macrovesicular steatosis, cholestasis, and glycogenated nuclei were seen in multiple cases from both patient populations, findings others have also noted.6 These changes may suggest certain diagnoses but are considered to be nonspecific in isolation.16,17 Glycogenated nuclei have been described in diabetes mellitus17; although these 2 findings were both more prevalent in our cardiac hepatopathy group, there was no statistically significant link between them (P >.99). Overall, given the nonspecificity of glycogenated nuclei, they should not be relied on in isolation to favor cardiac hepatopathy.

More concerning was the presence of a myriad of portal tract changes, including inflammation, fibrosis, and bile ductular reaction. As noted by Kakar et al,18 such findings may trigger consideration that a process other than outflow obstruction is to blame for liver pathology, such as chronic biliary disease; however, because they can be seen in both Budd-Chiari and cardiac hepatopathy, they should not be interpreted as ruling out these 2 possibilities. Another finding that could confound diagnostic interpretation is the presence of centrizonal ductular reaction and/or centrizonal arterioles, both of which were equally common in the 2 diagnoses. A recent report describing such findings in outflow obstruction directly correlated the prevalence of centrizonal arterioles to the degree of liver fibrosis,19 and we observed a similar correlation (quantitative data not shown).

Given the similarities in morphologic sequelae and etiologic concept, it may be considered that the 2 diseases cause liver injury through overlapping pathophysiologic mechanisms. Both involve prevention of normal venous flow from the liver, either through mechanical obstruction (thrombosis) or through congestion of the outflow tract. Furthermore, thrombosis has been postulated as a key mechanism of liver damage in both cardiac hepatopathy and Budd-Chiari.10,13

A handful of studies have sought to correlate morphologic changes in hepatic outflow obstruction to clinical disease severity or parameters such as symptom duration or right atrial pressure, primarily in cardiac hepatopathy.8,11,18 Along these lines, a staging system for congestive hepatic fibrosis in patients with cardiac hepatopathy was recently proposed.20 This system graded liver fibrosis on a 0 to 4 scale and found a significant correlation with right atrial pressure and right atrial and ventricular dilation. To our knowledge, a similar system has not been specifically proposed for Budd-Chiari.

Of note, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome follows a different pathophysiologic mechanism than Budd-Chiari and cardiac hepatopathy, as the sinusoidal endothelium itself becomes damaged.1,21 In our experience, the microscopic findings in acute sinusoidal obstruction syndrome are more pronounced and striking than in the other conditions, with exaggerated sinusoidal dilation and congestion. Patients with chronic disease demonstrate characteristic central vein fibrosis or occlusion, which also strongly suggests the diagnosis. Additionally, the disease is most often caused by myeloablative therapy prior to stem cell transplantation, meaning that the possibility of sinusoidal obstruction syndrome can be considered prior to biopsy review in patients with such a history.

Pathologic findings in hepatic outflow obstruction include expected observations (sinusoidal dilation and fibrosis, centrilobular necrosis) and more nonspecific changes. Pericellular/sinusoidal fibrosis and fibrosis surrounding the central vein are more common in cardiac hepatopathy, which is not unexpected, given the chronic nature of most heart failure. Conversely, centrilobular dropout and necrosis are more common in Budd-Chiari of any duration, consistent with its more acute mechanism of damage. As portal tract changes are common in both of these forms of outflow obstruction, they alone should not argue against these diagnoses. Knowledge of these histologic changes can assist in generating an appropriate differential diagnosis in patients without clinically confirmed cardiac hepatopathy or Budd-Chiari syndrome.

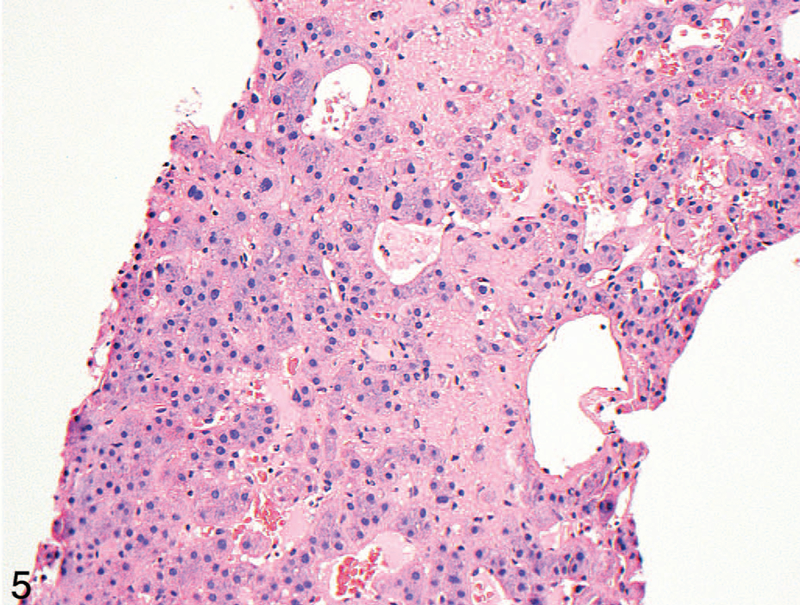

Figure 5.

High-power view of the case in Figure 4. Red blood cells can be seen in the space of Disse (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200).

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Contributor Information

Raul S. Gonzalez, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York.

Michael A. Gilger, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

Won Jae Huh, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

Mary Kay Washington, Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee.

References

- 1.Bayraktar UD, Seren S, Bayraktar Y. Hepatic venous outflow obstruction: three similar syndromes. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13(13):1912–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aydinli M, Bayraktar Y. Budd-Chiari syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13(19):2693–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valla DC. Primary Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Hepatol 2009;50(1):195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cazals-Hatem D, Vilgrain V, Genin P, et al. Arterial and portal circulation and parenchymal changes in Budd-Chiari syndrome: a study in 17 explanted livers. Hepatology 2003;37(3):510–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu RB, Chang CI, Lin FY, et al. Heart transplantation in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34(2):307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chokshi A, Cheema FH, Schaefle KJ, et al. Hepatic dysfunction and survival after orthotopic heart transplantation: application of the MELD scoring system for outcome prediction. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012;31(6):591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louie CY, Pham MX, Daugherty TJ, Kambham N, Higgins JP. The liver in heart failure: a biopsy and explant series of the histopathologic and laboratory findings with a particular focus on pre-cardiac transplant evaluation. Mod Pathol 2015;28(7):932–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers RP, Cerini R, Sayegh R, et al. Cardiac hepatopathy: clinical, hemodynamic, and histologic characteristics and correlations. Hepatology 2003; 37(2):393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefkowitch JH, Mendez L. Morphologic features of hepatic injury in cardiac disease and shock. J Hepatol 1986;2(3):313–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka M, Wanless IR. Pathology of the liver in Budd-Chiari syndrome: portal vein thrombosis and the histogenesis of veno-centric cirrhosis, veno-portal cirrhosis, and large regenerative nodules. Hepatology 1998;27(2):488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arcidi JM Jr, Moore GW, Hutchins GM. Hepatic morphology in cardiac dysfunction: a clinicopathologic study of 1000 subjects at autopsy. Am J Pathol 1981;104(2):159–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibarrola C, Castellano VM, Colina F. Focal hyperplastic hepatocellular nodules in hepatic venous outflow obstruction: a clinicopathological study of four patients and 24 nodules. Histopathology 2004;44(2):172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wanless IR, Liu JJ, Butany J. Role of thrombosis in the pathogenesis of congestive hepatic fibrosis (cardiac cirrhosis). Hepatology 1995;21(5):1232–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunt EM, Gouw AS, Hubscher SG, et al. Pathology of the liver sinusoids. Histopathology 2014;64(7):907–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghaferi AA, Hutchins GM. Progression of liver pathology in patients undergoing the Fontan procedure: chronic passive congestion, cardiac cirrhosis, hepatic adenoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129(6):1348–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burt AD, Mutton A, Day CP. Diagnosis and interpretation of steatosis and steatohepatitis. Semin Diagn Pathol 1998;15(4):246–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abraham S, Furth EE. Receiver operating characteristic analysis of glycogenated nuclei in liver biopsy specimens: quantitative evaluation of their relationship with diabetes and obesity. Hum Pathol 1994;25(10):1063–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakar S, Batts KP, Poterucha JJ, et al. Histologic changes mimicking biliary disease in liver biopsies with venous outflow impairment. Mod Pathol 2004; 17(7):874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krings G, Can B, Ferrell L. Aberrant centrizonal features in chronic hepatic venous outflow obstruction: centrilobular mimicry of portal-based disease. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38(2):205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai DF, Swanson PE, Krieger EV, et al. Congestive hepatic fibrosis score: a novel histologic assessment of clinical severity. Mod Pathol 2014;27(12):1552–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeLeve LD, Shulman HM, McDonald GB. Toxic injury to hepatic sinusoids: sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (veno-occlusive disease). Semin Liver Dis 2002;22(1):27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]