Abstract

Background

Fractures of the mandible are the commonest facial fractures and various treatment modalities exist like wire osteosynthesis and the use of miniplates and screw with most of the industrially developed world leaning towards the use of miniplates in the treatment of these fractures. The use has however been limited in developing countries (including Nigeria) mostly due to the cost of the plates and screws.

Aim and Objectives

To identify the versatility of miniplates in the treatment of mandibular fractures at a tertiary care centre in a developing country.

Methods

All Subjects aged 16 years and above in whom mandibular fractures were diagnosed were recruited over a two year period. Patients were treated under general anesthesia using either the miniplates and screws or wire osteosynthesis while some patients had both miniplates and maxillo-maxillary fixation.

Results

A total of 94 patients were recruited for the study of which 89.4% were males while the age group 16 to 25 years constituted the majority. Though 29.8% of the study population was involved in business, only 9.6 % were professional motorcyclists. Motorcycle-related road traffic crashes constituted the commonest aetiologic agent with 41.5%, while combination fractures were the commonest fracture types seen in 54.3% of the study participants. Of the 94 patients, 77.7% had treatment of mandibular fractures by open reduction and immobilization with mini plates, while 7.4% had mini plates with Maxillo-maxillary fixation and 14.9% had wire osteosynthesis only. The site of fracture was significantly associated with the treatment modality (p= 0.02).

Conclusion

This study showed that the choice of fixation appliances in mandibular fractures was influenced by the number of fractures and the multiplicity of fracture sites. Miniplates offered functionally stable fixation with minimum complications

Keywords: Mandibular fractures, Miniplates, Osteosynthesis, Versatility

Introduction

Mandibular fractures are among the most common of facial fractures. Causes of mandibular fractures include motor vehicle crashes, falls, assault, sports-related injuries and more recently motorcycle accidents. In Western Europe and parts of sub- Saharan Africa such as Zimbabwe and South Africa, mandibular fractures are more often caused by interpersonal violence in form of fights, assaults and gunshot injuries. However, in some developing countries, studies have shown that road traffic crashes (RTCs) constitute the predominant cause of trauma to the mandible1, 2, 3. In Nigeria, increasing influence of assault due to the current wave of armed insurgency and gun violence can also be contributory4.

Various methods abound in the treatment of fractures of the mandible5, ranging from simple Maxillo-mandibular fixation (MMF) to rigid internal fixation of the bone fragments6. The treatment outcome of mandibular fractures is mainly dependent, among other things, on the degree of injury, type of fracture, the expertise of the surgeon, and available technology2, 4, 5.

The use of wire osteosynthesis and MMF has decreased considerably in western and other developed countries because of the disadvantages associated with them such as prolonged hospital stay, decreased pulmonary function and weight loss7. While intraosseous wiring prevents distraction, it does not provide sustained inter-fragmentary compression. These, among other reasons, led to increased preference for open reduction and internal fixation with miniplates. In addition, miniplate osteosynthesis sometimes eliminates the need for MMF and facilitates stable anatomic reduction while reducing the risk of postoperative displacement of the fractured fragments, allowing immediate return to function8, 9. However, in our environment, the conventional method of treating mandibular fractures is by MMF with or without wire osteosynthesis10-12>. Miniplates are not commonly used and Okoturo et al11 suggested high cost of the titanium plates as the reason behind non affordability by patients.

There is no database on mandibular fracture treatment using miniplates in this relatively new centre. Moreover, only few centers in Nigeria have reported on the use of miniplate osteosynthesis in mandibular fracture treatment. This study, therefore, is a cross sectional analysis on the versatility of miniplate usage in the treatment of mandibular fractures seen in Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH) over a period of 24 months. The study is aimed at investigating the sociodemographic characteristics, universal application or otherwise of miniplates in mandibular fracture treatment and general complication rates associated with such usage.

Patients and Methods

All the patients 16 years and above managed for mandibular fractures were recruited for the present study based on convenient sampling method as they reported in the outpatient clinics of the Dental and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH), Kano, Nigeria as well as the Accident and Emergency Department of the same hospital over a period of 24 months (from June, 2012 to May, 2014). Diagnosis of fractured mandible was made based on detailed history, clinical examination as well as radiological investigations. Laboratory investigations such as full blood count, urea and electrolytes were carried out prior to surgery. Subjects with underlying systemic conditions such as hypertension and uncontrolled diabetes were excluded from the study. All the subjects were admitted 72 hours prior to surgery with prophylactic pre-operative scaling and polishing done during this period.

Treatment was based on the adopted AO revised principles of fracture treatment using miniplates and screws13. For the purpose of this study stainless steel miniplates and screws (OrthomaxR India) were used. Intraoperatively, some of the subjects had MMF in addition for a limited period of time, while others that could not afford the miniplates were treated with MMF and/or wire osteosynthesis only. All surgical treatments were carried out under general anesthesia.

Postoperative follow up examinations were performed for up to 6 months at intervals of 1, 2, 4 and 6th weeks and then 3 and 6 months after discharge from the hospital. Postoperative plain radiographs were taken at 1st and 6th week to assess the immediate postsurgical outcome and bone union respectively. Those treated with wire osteosynthesis had their MMF wires removed at 6th week14.

Data collected included the demographics, trajectory of injury, sites of fractures, treatment methods and complications. The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 16.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Qualitative data were presented as percentages while quantitative data was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Chi square was used to determine significant association between categorical variables with a p value of 0.05 or less considered significant.

Results

Majority of the patients were males (89.4%) while the age group 16 to 25 years constituted the majority of the study participants. Though 29.8% of the study population was involved in business, surprisingly only 9.6 % of them were professional motorcyclists. (Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the 94 patients studied for mini plate versatility)

Table 1. SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS .

| Characteristics | No | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Males | 84a | 89.4 |

| Females | 10b | 10.6 |

| AGE GROUP (YEARS) | ||

| 16 – 25 | 50 | 53.2 |

| 26 -35 | 34 | 36.2 |

| > 36 | 10 | 10.6 |

| OCCUPATION | ||

| Business | 28 | 29.8 |

| Public servant | 6 | 6.4 |

| Artisan | 24 | 25.5 |

| Student | 14 | 14.9 |

| Driver | 9 | 9.6 |

| Motorcyclist(professional) | 9 | 9.6 |

| Dependent | 4 | 4.3 |

| EDUCATION | ||

| Primary | 11 | 11.7 |

| Secondary | 41 | 43.6 |

| Tertiary | 5 | 5.3 |

| Islamic | 28 | 29.8 |

| Uneducated | 9 | 9.6 |

| a,b p<0.05 | ||

Table 2. The aetiology and various types of mandibular fractures treated .

| Variable | No | Percentage (%) |

| Aetiology | ||

| Motor cycle | 39 | 41.5 |

| Motor vehicle | 31 | 33.0 |

| Bicycle | 5 | 5.3 |

| Fight/ assault | 7 | 7.4 |

| Sports | 3 | 3.2 |

| Fall | 5 | 5.3 |

| Missile injury | 4 | 4.3 |

| Types: | ||

| Symphyseal | 2 | 2.1 |

| Parasymphyseal | 3 | 3.2 |

| Body | 22 | 23.4 |

| Angle | 11 | 11.7 |

| Ramus | 1 | 1.1 |

| Condyle | 4 | 4.3 |

| Combination | 51 | 54.3 |

Of the 94 patients, 73 (77.7%) had treatment of mandibular fractures by open reduction and immobilization with mini plates, while 7 (7.4%) had mini plates with MMF and 14 (14.9%) had wire osteosynthesis only.

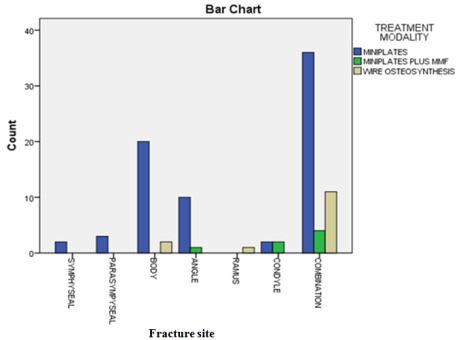

The influence of the location of the fracture site to the choice of treatment was subjected to test of significance and it was observed that the site of fracture was significantly associated with the treatment modality (p= 0.02) as shown in Table 3 and figure 1.

Table 3. Influence of location of fracture on choice of treatment modality .

| Fracture type | Treatment Modality | p-value | ||

| Mini plates n (%) | Mini-plates plus MMF n (%) | Wire osteosynthesis n (%) | ||

| Symphyseal | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 |

| Parasymphyseal | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Body | 20 (27.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (14.3) | |

| Angle | 10 (13.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ramus | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Condyle | 2 (2.7) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Combination | 36 (49.3) | 4 (57.1) | 11 (78.6) | |

Figure 1. Treatment modality versus the fracture site.

The complications included infection 13 (13.8%), keloids 1 (1.1%), non-union

1 (1.1%), mal-union 4 (4.3%), nerve injury 1 (1.1%), fractured plates 1 (1.1%), combinations 1 (1.1%), and hypertrophic scar 1 (1.1%). However, 71 (75.5%) of the participants reported no complication.

Table 4 shows the distributions of complications with or without removal of mini plates.

Table 4. Complications and removal rates of mini plates among participants .

| Variable | Age group | Side | No of bones fractured | Types of fractures | ||||||||||||

| 16 -25 | 26- 35 | >35 | Right | Left | 1 | 2 | 3 | Comminuted | Sy | Par | Bo | Ang | Ram | Con | Com | |

| Complications: | ||||||||||||||||

| YES | 13 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 16 |

| NO | 37 | 28 | 6 | 15 | 17 | 29 | 38 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 35 |

| Miniplate removal | ||||||||||||||||

| YES | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| NO | 38 | 31 | 7 | 17 | 18 | 31 | 39 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 37 |

| Sy = Symphyseal, Par = Parasymphyseal, Bo = Body, Ang = Angle, Ram = Ramus, Con = condyle, Com = combination. | ||||||||||||||||

Discussion

Mandibular fractures world over has been observed to occur more in males than in females and has remained fairly constant at a ratio of approximately 3 :1 with a range of 2:1 to 9:1 as reported by several authors from different parts of the world including Nigeria7,15,16. The reason for male preponderance has been attributed to greater male aggressiveness with a stronger propensity for injuries, facial included17. There was a higher male preponderance in this study with 89.4% males which approximates a ratio of 9: 1 (Table 1).

The 16-25 years age group was mostly affected in this study. Mandibular fractures resulting from trauma is typically a problem of young urban males17,18, although, this opinion has been questioned since the elderly now live a more active lifestyle with increased longevity19. Most authors2,3,5,6,20,21, however, are in agreement that mandibular fractures resulting from trauma occur commonly between the second and third decades of life. Several reasons have been adduced for the high occurrence of mandibular fractures in this age group comprising young, upwardly mobile and active; others include involvement in “hard drugs” and dangerous driving, to tendency in making numerous journeys in search of employment7,16,22, even though mandibular fractures can affect all age groups23.

In this study, we observed that most of the patients were business people constituting as much as 29.8% and artisans 25.5% as shown in Table 1, while professional motorcyclists constituted 9.6%. This may be explained by the fact that recent policies by the government in the city led to a reduction in the number of commercial motorcycle riders on the roads with the banning of commercial motorcycles. Furthermore, most business men and women travel on poorly maintained roads which make them more susceptible to road crashes with resultant mandibular fractures. The finding of a high incidence of mandibular fractures among artisans is also worthy of note. This may be attributed to the dangers associated with their jobs in terms of itinerary, and probably lack of proper safety gears with a safe working environment. The implications of these findings showed a need to improve the road maintenance culture by various authorities in Nigeria and also provision of other modes of transportation like fast trains that would make travelling safer and easier. There is also the need to make the work environment for artisans as accident free as possible and provide basic safety gears.

This study showed that the use of miniplates was common (77.7%) while 14% had wire osteosynthesis only as their modality of treatment. This may be attributed to the ease of use, increasing expertise and the types of fractures. There was also the fact that the prices of bone plates were initially subsidized and subsequently patients paid only the cost price of the bone plates and screws. The rate of miniplates used was found to be quite high(77.7%) unlike most centers in Nigeria that reported rates ranging from 0% to 9.1%24,25, while some developed countries reported rates of 18%26 to 45.7%27. However, a study in India reported a similar rate of use of miniplates of 70.7%28.

It is, however, important to note that the type of fracture was actually found to significantly affect the use of miniplates (p=0.02) as shown in Table 3, with combination fractures greatly influencing the need to use miniplates. Based on these findings, it is advocated that bone plates could be subsidized in developing countries through the help of donor agencies and the universal health insurance scheme among others.

The commonest complication observed with the use of miniplates was infection (13.8%), which necessitated the removal of the bone plates in some cases. The infection rate was similar to a study24 in southern Nigeria, although the number of patients they studied were fewer. However, the use of miniplates was observed to be generally quite safe being uneventful in 75.5% of the patients. There was a direct relationship between the frequency of complications and the number of bones/ number of fracture types involved with two or more fracture types having more complications.

The limitation of this study possibly was the short follow up period of 6 months.

Conclusions

This study showed that the choice of fixation appliances in mandibular fractures was influenced by the number of fractures and the multiplicity of fracture sites. Miniplates offered functionally stable fixation with minimum complications.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Prof. A.L Ladeinde, Prof S.O Ajike and Dr H. O. Akhiwu for their contribution to the research and preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Kumaran PS, Thambiah L. Versatility of a single upper border miniplate to treat mandibular angle fractures: A clinical study. Case report - maxillofacial surgery. 2011;1(2):160–165. doi: 10.4103/2231-0746.92784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akhiwu BI, Adebola RA, Ladeinde AL, Osunde OD, Lawal IU. Mandibular fractures: Demographic and clinical characteristics. Nig J Orthopaedic Trauma. 2012;11(2):113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adebayo ET, Ajike SO, Adekeye EO. Analysis of the pattern of Maxillofacial fractures in Kaduna, Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(6):396–400. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Udeabor SE, Akinbami KS, Obiechina AE. Maxillofacial fractures: Etiology, pattern of presentation, and treatment in University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. J Dent Surg. 2014;20(14):151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhiwu BI, Kolo SE, Amole IO. Analysis of complication of mandibular fractures. Afri J Trauma. 2014;3(1):24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Trends in the characteristics of maxillofacial fractures in Nigeria. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2003;61(10):1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adeyemo WL, Ladeinde AL, Ogunlewe MO, James O. Trends and characteristics of oral and maxillofacial injuries in Nigeria: a review of the literature. Head & Face Medicine. 2005;1(7):1–18. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcantonio G, Vieria H. Fixation of mandibular fractures with miniplates. Review of 191cases. J Oral Maxifac Surg . 2003;61:430–436. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto K, Matsusue Y, Horita S, Murakami K, Sugiura T, Kirita T. “Clinical analysis of midfacial fractures,” . Materia Socio Medica. 2014;26(1):21–25. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.26.21-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fashola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Incidence and pattern of maxillofacial fractures in the elderly. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg . 2003;32(2):206–208. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okoturo EM, Arotiba GT, Akinwande JA, Ogunlewe MO, Gbotolorun OM, Obiechina AE. Miniplate osteosynthesis of mandibular fractures at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital Nig. Qt J Hosp Med. 2008;18(1):45–49. doi: 10.4314/nqjhm.v18i1.44962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adewole RA. An audit of mandibular fracture treatment methods at a Military Base Hospital Yaba, Lagos Nigeria: A 5-year retrospective study. Nig J Clinical Pract . 2001;4(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis E. Treatment methods for fractures of the mandibular angle. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28:243–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghazal G, Jacquiery C, Hammer B. Non surgical treatment of mandibular fractures: Survey of 28 patients. . Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:141–145. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olasoji HJ, Tahir A, Arotiba GT. Changing picture of facial fractures in Northern Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;40:140–143. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adebayo ET, Ajike OS, Adekeye EO. Analysis of the pattern of maxillofacial fractures in Kaduna, Nigeria. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(6):396–400. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fashola AO, Obiechina AE, Arotiba JT. Incidence and pattern of maxillofacial fractures in the elderly. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(2):206–208. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olasoji HO, Tahir AA. Trends in handgun injuries of the maxillofacial region in Maiduguri, North Eastern Nigeria. Afri J of Trauma. 2004;2(2 - 4):83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrera JE, Stephen GB, Hassan HR. Fractures of the mandibular angle. e- medicine.com, Inc. 2006. Feb 06, http://www/e-med-com/content/1/12 pp. 1–12.http://www/e-med-com/content/1/12

- 20.Erol B, Tanrikulu R, Gorgun B. Maxillofacial fractures: Analysis of demographic distribution and treatment in 2901 patients (25 years experience). J Craniomaxillofac Surg . 2004;32:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saheeb BD, Ugbodaga PI. Profile of maxillofacial injuries at an Accident and Emergency Centre. . Nig J Surg Sci. 2003;13(2):37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ugboko VI, Odusanya SA, Fagade OO. Maxillofacial fractures in a semi-urban Nigeria Teaching Hospital. A review of 442 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;27:286–289. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(05)80616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ezekiel TA. Maxillofacial fractures in Port Harcourt, Nigeria: A case report. Afr J Trauma. 2004;2(2 - 4):85–87. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adewole RA. An audit of mandibular fracture treatment methods at military base hospital Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria (A 5 year retrospective study). Nig J Clin Prac. 2001 Jun4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udeabor SE, Akinbami BO, Yaehere KS, Obechina AE. Maxillofacial fractures: aetiology, pattern of presentation and treatment in University of Portharcourt , Nigeria. Journal of dental surgery . 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham-Dand N, Barthelemy I, Orliagnet T, Artola A, Mondie JM, Dallel R. Etiology , distribution, treatment modalities and complications of maxillofacial fractures. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19:e261–e269. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghodake MH, Bhoyar SC, Shah SV. Prevalence of mandibular fractures reported at CSMSS Dental College, Aurangabad from Feb 2008- September 2009. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent . 2013;3:51–58. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.122428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadre KS, Halli R, Joshi S, Ramanojam S, Gadre PK, Kunchur R. Incidence and pattern of craniomaxillofacial injuries: a 22 year retrospective analysis of cases operated at major trauma hospitals/ centres in Pune, India. Journal of maxillofacial and Oral surgery. 2013;12:372–378. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0446-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]