Abstract

Background

Perforations of the stomach and duodenum are common complications of peptic ulcer disease (PUD), abuse of non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and gastric cancer. Being a life threatening complication of PUD, it needs special attention with prompt resuscitation and appropriate surgical management if morbidity and mortality are to be avoided.

Aim

To determine the pattern and management outcome of perforated peptic ulcer disease PUD as seen in University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH), Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria).

Methodology

All the patients with perforated PUD that were managed at UPTH between January 2006 and December 2014 were studied. Relevant data were extracted from the case notes and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.

Results

Thirty six patients with perforated PUD were evaluated consisting of 28 males and 8 females with a male to female ratio of 3.5:1. Their ages ranged from 24 to 65 years with a mean of 42.1± 12.3 years and the peak age was at the third decade. After adequate resuscitation, all the patients had exploratory laparotomy. In 26 (72.2%) patients, the perforation was in the duodenum while in 10 (27.8%), it was in the stomach. Thirty two (88.9%) patients had Graham’s omental patch repair of the perforation while simple closure only was done in 4 (11.1%) patients. Surgical site infection was the commonest post operative complication which was seen in 7 (19.4%) patients while 4 patients died giving a mortality rate of 11.1%.

Conclusion

Perforated peptic ulcer predominantly affected young males and Graham’s omental patch followed by Helicobacter pylori eradication was an effective treatment modality.

Keywords: Perforated peptic ulcer disease, Pattern, Late presentation, Effective closure, Good outcome, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Introduction

Perforations of the stomach and duodenum are common in surgical practice and do occur as a complication of peptic ulcer disease (PUD), abuse of non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and gastric cancer1,2. Despite the widespread use of anti secretory agents and Helicobacter Pylori eradication therapy, the incidence has remained relatively unchanged3. Perforations due to peptic ulcer is a serious complication which affects an average 2-10% of peptic ulcer patients4 and having an overall mortality of 10%5, although some authors report ranges between 1.3 and 20%6.Being a life threatening complication of PUD, it needs special attention with prompt resuscitation and appropriate surgical management if morbidity and mortality are to be avoided7This study seeks to determine the pattern of presentation and management outcome of perforated PUD managed in UPTH over a 9 year period.

Patients & Methods

All the patients with perforated PUD managed at University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria between January 2006 and Dec 2014 except for three patients whose case records were incomplete, were studied. Data which included age, sex,duration of symptoms before presentation at the hospital, history of PUD, use of NSAIDS, clinical presentation, findings of relevant investigations, operation findings, treatment, outcome of treatment and post operative complications were extracted from the case notes and analysed using SPSS version 17.

Results

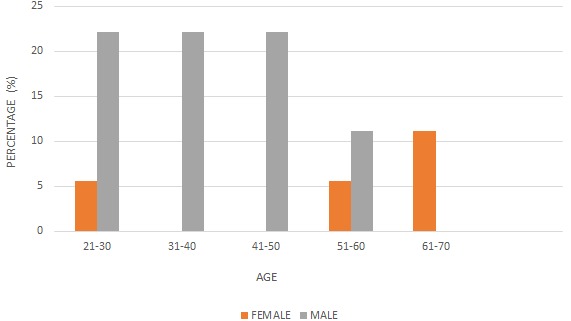

Thirty six patients with perforate peptic ulcer were evaluated consisting of 28 males and 8 females with a male to female ratio of 3.5:1.Their ages ranged from 24 to 65 years with a mean of 42.1± 12.3 years and the peak age incidence was at the 3rd decade. ( Figure1).Duration of symptoms before presentation at the hospital was from 2 hours to 6 days with a mean duration of 3.7± 1.4 days. Four (11.1%) patients presented within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms. The rest presented between 1 and 6 days after the onset of symptoms. (as shown in Table 1).Twenty four (55.6%) patients had a previous history of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) with symptoms ranging from 1 to 8 years with an average duration of 4.3± 1.1 years while 12 (33.3%) patients had been on non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) ranging from 1 to 3 years with an average of 1.7± 0.8 years. The remaining 4 (11.1%) patients presented at the hospital for the first time with no prior history of PUD or NSAID ingestion.The common presenting symptoms were severe epigastric pain, vomiting and abdominal distension in 36 (100%), 22 (66.7%) and 10 (27.8%) patients respectively. Presenting features are as shown in Table 2. Signs of peritonitis were demonstrable in 30 (83.3%) patients with 8 (22.2%) of them presenting in shock (systolic blood pressure ˂ 90mmHg). Eighteen (50%) patients had plain chest/abdominal radiograph done with free gas under the diaphragm demonstrated in 11 (61.1%) of them. After adequate resuscitation, all the patients had emergency exploratory laparotomy. In 26 (72.2%) patients, the perforation was on the anterior aspect of the first part of duodenum while in 10 (27.8%) patients, it was on the stomach (6(16.7%) on the lesser curvature, 2 (5.6%) on the greater curvature and 2 (5.6%) on the pre pyloric region). Four (11.1%) of the perforations were of minimal size while 32 (88.9%) of them were massive (˃10mm). Thirty two (88.9%) patients had Graham’s omental patch of the perforations while in 4 (11.1%) patients, simple closure was done. All the patients had adequate peritoneal larvage. Subsequently, all the patients were placed on triple regimen which included a proton pump inhibitor, metronidazole and amoxicillin.Surgical site infection was the commonest post operative complication, which affected 7 (19.4%) patients. Other post operative complications were as shown in Table 3.The duration of hospital stay ranged from 9 to 35 days with a mean of 17.2± 4.2 days.Four patients died giving a mortality rate of 11.1%. Two patients had acute kidney injury with electrolyte derangement while another 2 patients had leakage from closure site with septicaemia.

Figure 1. Age and sex distribution.

Table 1. DURATION OF SYMPTOMS.

| NUMBER OF DAYS | NUMBER OF PATIENTS (%) |

| 0 – 1 | 4 (11.1) |

| 1 – 3 | 16 (44.4) |

| 4 – 6 | 16 (44.4) |

Table 2. CLINICAL FEATURES.

| S/N | FEATURES | NUMBER OF PATIENTS (%) |

| 1 | ABDOMINAL PAIN | 36 (100) |

| 2 | VOMITTING | 22 (66.7) |

| 3 | ABDOMINAL DISTENSION | 10 (27.8) |

| 4 | FEVER | 8 (22.2) |

| 5 | PASSAGE OF BLOODY STOOL | 2 (5.6) |

| 6 | CONSTIPATION | 8 (22.2) |

| 7 | SIGNS OF PERITONITIS | 30 (83.3) |

Table 3. Post-operative complications.

| COMPLICATIONS | NUMBER OF PATIENT (%) |

| SURGICAL SITE INFECTION | 7 (19.4) |

| ACUTE KIDNEY INJURY | 2 (5.6) |

| LEAKAGE OF REPAIR | 2 (5.6) |

| INCISIONAL HERNIA | 2 (5.6) |

Discussion

A total of 36 cases of perforated peptic ulcer disease were treated in our hospital over a 9 year period giving an average of 4 cases per year. This is similar to the observation in Ile-Ife8 and other centres9,10. This may be attributable to the use of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) which are effective in care and are common over the counter drugs in our environment.Males predominated in our study (77.8%) giving a male to female ratio of 3.5:1 and this was in agreement with the findings of other studies where the male to female ratio ranged from 3.3:1 to 9:111,12. From this study, perforated peptic ulcer disease commonly affected young and middle age group where the commonest age at presentation was between 21 and 50 years with a mean of 42.1± 12.3 years which is in consonance with previous reports13,14,15. However, Ohene-Yeboah et al11 reported a mean of 64.8± 11.4 years. In the series involving caucassians, the majority of the patients were above 60 years and the incidence was higher in elderly females16.Most of our patients (55.6%) had past history of chronic PUD. Similar observations were made by Nuhu et al9 from Maiduguri and Lawal et al13 from Ile-Ife who recorded previous history of PUD in 71 and 47% of their patients respectively. This is in contrast to some other African studies where more than 60% of their patients had no past history suggestive of PUD7,17. The reason for this difference is not quite apparent. Similarly, use of NSAIDS is an important cause of perforated PUD in the west17. NSAIDS inhibit prostangladin synthesis, so further reducing gastric mucosal blood flow18. Use of NSAIDS was seen in 33.3% of our patients which was low compared to reports from Ghana11. This could be due to the younger age groups in this study (with a mean age of 42.1 years compared to ˃60 years in the Ghanian study). Long term NSAID use is common in the elderly for care of osteoarthritis.The time lapse between an episode of acute duodenal ulcer perforation and surgical intervention is a critical determinant of survival19. In this study, most (88.9%) of our patients presented late i.e. ˃ 24 hours from the onset of symptoms. This is in agreement with other studies from in most developing countries7,9,20. Late presentation in our study may be attributed to poverty and lack of awareness of the disease by the patient and relatives and poor index of suspiscion by some managing clinicians. A mean period of 22.15 hours between perforation and surgical intervention was reported in 156 patients by Bin-Taleb et al15. A corresponding low mortality of 3.9% was reported in the same study compared to the 11.5% in this study.In agreement with other studies7,9,17, the diagnosis of perforated PUD was mainly clinical and radiological in our series, with typical signs and symptoms of peritonitis manifesting especially in those with a past history of chronic PUD. This was supported by identification of free air under the diaphragm in plain chest radiograph and the diagnosis confirmed at laparotomy. It has been documented that in perforated PUD, the free subdiaphragmatic air is less likely to be seen if the time interval between perforation and radiological examination was short21. CT scan with oral contrast which is considered as the gold standard for diagnosis of a perforation and abdominal ultrasound scan have been found to be superior to plain radiographs in the diagnosis of free intraperitoneal air22,23. These imaging studies were not used in the diagnosis of free intraperitoneal air in our study. Plain radiographs of the chest/abdomen were used to establish the diagnosis of free intraperitoneal fluid and air under the diaphragm in 61.1% of patients. This was similar to 63.5 and 65.8% reported by Nuhu et al9 and Chalya et al17 respectively.In this study, duodenal ulcer perforation was the commonest type of perforation seen with a duodenal ulcer to gastric ulcer perforation ratio of 2.6:1. Gastric ulcer had been considered to be a rare disease in Africa being 6 to 30 times less common than duodenal ulcer11,24. A study in Tanzania documented a ratio of 12.7:117 in favour of duodenal ulcer which was similar to 11.5:1 from a Kenyan study25. Lower duodenal to gastric ulcer ratios of 3:1 to 4:1 had been reported from the western world11,25 while a study in Ghana reported a higher incidence of gastric ulcer perforations11. There was no identifiable reason to account for these differences in duodenal to gastric ulcer ratio.The findings at laparotomy varied depending on the site, size and duration of the perforation. The size of the perforation determines the amount of peritoneal contamination19. Thirty two (88.9%) of our patients had large perforations which was similar to the 82.7% reported by Nuhu et al9. The degree of peritoneal soilage was crucial in patients with peritonitis due to perforated peptic ulcer disease and early surgical intervention prevented further contamination of the peritoneal cavity while removing the source of infection.

The implication of this study is that despite the fact that perforated peptic ulcer is relatively common in our environment, Graham’s omental patch of the perforation followed by Helicobacter pylori eradication is an effective mode of treatment.In this study, Graham’s omental patch of the perforations was the procedure of choice in our centre and this was done in 89.9% of patients. Similar surgical treatment pattern was reported in other series7,9,17,21. It was a rapid, easy and life saving surgical procedure that has been shown to be effective with acceptable mortality and morbidity26. It was the surgical procedure of choice in most centres and followed by eradication of Helicobacter Pylori to avoid recurrence26.Overall complication rate was 36.1% which was comparable to the findings of other workers21,27. Surgical site infection was the commonest post operative complication which was also in keeping with other studies9,26,28 which was attributed to contamination of the laparotomy wound during the surgical procedure.The mortality rate of 11.1% was similar to the report of Etonyeaku et al8 but low when compared to similar studies in the sub region.

The retrospective nature of this study was the main limitation.

Conclusions

This study has shown that perforated peptic ulcer remains a clinical problem in our environment and predominantly affects young males. Graham’s omental patch of the perforation followed by Helicobacter pylori eradication was effective with good results in majority of cases despite late presentation in our centre.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Grant support: None

References

- 1.Svanes C. Trends in perforated peptic ulcer: Incidence, Aetiology, Treatment and Prognosis. World J Surg. 2000;24:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s002689910045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dakubo JC, Naaeder SB, Clegg-Lamptey JN. Gastroduodenal peptic ulcer perforation. East Afri Med J. 2009;86:100–109. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v86i3.54964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oribabor FO, Adebayo BO, Aladesanmi T, Akinola DO. Perforated peptic ulcer: Management in a Resource Poor, Semi Urban Nigerian Hospital. Niger J Surg. 2013;19:13–15. doi: 10.4103/1117-6806.111499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Testini M, Portincasa P, Piccinni G, Lissidini G, Pellegrini F, Grecol L. Significant factors associated with fatal outcome in emergency open heart surgery for perforated peptic ulcer. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2388–2340. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajesh V, Sarathchandra S, Smile SR. Risk factors predicting operative mortality in perforated peptic ulcer disease. Trop Gastroenterol . 2003;24:148–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermansson M, Von Holstein CS, Zilling T. Surgical approach and prognostic factors after peptic ulcer perforation. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:566–572. doi: 10.1080/110241599750006479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elnagib E, Mahadi SE, Mohammed E, Ahmed ME. Perforated peptic ulcer in Khartoum. Khartoum Med J. 2008;1:62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etonyeaku AC, Agbakwuru EA, Akinkuolie AA, Omotola CA, Talabi AO, Onyia CU, Kolawole OA, Aladesuru OA. A review of the management of perforated duodenal ulcers at a tertiary hospital in South Western Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:907–913. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i4.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nuhu A, Madziga A, Gali B. Acute Perforated Duodenal Ulcer in Maiduguri. West Afr J Med. 2009;28:384–387. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v28i6.55032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irabor DO. An audit of peptic ulcer surgery in Ibadan, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2005;24:241–245. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v24i3.28206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohene-Yeboah M, Togbe B. Perforated gastric and duodenal ulcers in an urban African Population. West Afr J Med. 2006;25:205–211. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v25i3.28279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawal OO, Fadiran OA, Oluwole SF, Campbell B. Clinical pattern of perforated prepyloric and duodenal ulcer at Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Trop Doct. 1998;28:152–155. doi: 10.1177/004947559802800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffin GE, Organ CH. The natural history of perforated duodenal ulcer treated by suture plication. Ann Surg . 1976;183:382–385. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197604000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bin-Taleb AK, Razzaq RA, Al-Kathiri ZO. Management of perforated peptic ulcer in patients at a teaching hospital. Saudi Med J. 2004;53:378–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walt R, Katschinski B, Logan R, Ashley J, Langman M. Rising frequency of ulcer perforation among elderly people in the United Kingdom. Lancet. 1986;3:489. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Koy M, McHembe MD, Jaka HM, Kabangila R, Chandika AB, Gilyoma JM. Clinical profile and outcome of surgical treatment in perforated peptic ulcers in Northwestern Tanzania: A tertiary hospital experience. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collier DS, Pain JA. Non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer perforation. GUT. 1985;26:359–363. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.4.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subedi SK, Afaq A, Adhikari S, Niraula SR, Agrawal CS. Factors influencing mortality in perforated duodenal ulcer following emergency surgical repair. J Nepal M Assoc. 2007;46:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajao OG. Perforated duodenal ulcer in a tropical African population. J Natl Med Assoc. 1979;71:272–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan SH, Aziz SH, Ul-Haq MI. Perforated peptic ulcer: a review of 36 cases. Professional Med J. 2011;18:124–127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amela S, Serif B, Lidija L. Early radiological diagnostics of gastrointestinal infection in the management of peptic ulcer perforation. Radiol Oncol. 2006;40:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen SC, Yen ZS, Wang HP. Ultrasonography is superior to plain radiography in the diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum. Br J Surg. 2002;89:351–354. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umerah BC, Singarayar J, Ramzan MK. Incidence of peptic ulcer in the Zambian African- a radiological study. Med J Zambia. 1987;12:117–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuremu RT. Surgical management of peptic ulcer disease. East Afr Med J . 2002;76:454–456. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i9.9115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasio NA, Saidi H. Perforated peptic ulcer disease at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East and Centr Afr J Surg . 2009;14:13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee FY, Leung KL, Lai BS, Ng SS, Dexter S, Lau WY. Predicting mortality and morbidity of patients operated on for perforated peptic ulcer. Arch Surg. 2001;139:90–94. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khalil AR, Yunas M, Jan QA, Nisar W, Imran M. Graham’s omentopexy in closure of perforated duodenal ulcer. J Med Sci . 2010;18:87–90. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ersumo TW, Merksi Y, Kotisso B. Perforated peptic ulcer in Tikur Anbessa Hospital: A review of 74 cases. Ethiop Med J . 2005;43:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]