Abstract

Study Design

This study is a Therapeutic Retrospective Cohort Study

Objective

This study aims to determine if sexual function is relevant for patients with SPS and DS and to determine the impact of operative intervention on sexual function for these patients.

Summary of Background Data

The benefits of non-operative versus operative treatment for patients with spinal stenosis (SPS), and degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS) with regards to sexual function are unknown.

Methods

Demographic, treatment, and follow up data, including the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), was obtained on patients enrolled in the SPORT study. Based on the response to question #9 in the ODI, patients were classified into a sexual life relevant (SLR) or sexual life not relevant (NR) group. Univariate and Multivariate analysis of patient characteristics comparing the NR and SLR group was performed. Operative treatment groups were compared to the non-operative group with regards to response to ODI question #9 to determine the impact of surgery on sexual function.

Results

1235 patients were included to determine relevance of sex life. 366 patients (29%) were included in the NR group. 869 patients (71%) were included in the SLR group. Patients that were older, female, unmarried, had 3 or more stenotic levels, and had central stenosis were more likely to be in the NR group. 825 patients were included in the analysis comparing operative versus non-operative treatment. At all follow up time points the operative groups had a lower percentage of patients reporting pain with their sex life compared to the non-operative group (p<0.05 at all time points except between >1 level fusion and non-operative at 4 years follow up).

Conclusions

Sex-life is a relevant consideration for the majority of patients with DS and SPS; operative treatment leads to improved sex-life related pain.

Keywords: Sex Life Related Pain, Spinal Stenosis, Degenerative Spondylolisthesis, SPORT study

Introduction

Sexuality is an important part of life for many individuals. Chronic back pain has been shown to have negative consequences on sexual function, which can contribute to a deterioration in quality of life.1–4 Previous studies have evaluated sexual function in patients with chronic pain, cardiac disease, and rheumatic conditions, and hip arthritis,2,5,6 and some have evaluated sexual function in patients undergoing spinal surgery.1,7–9 These studies show that sexual function is generally improved postoperatively when compared to preoperative function. However, these studies were comprised of a small sample size, lacked a non-operative control group and focused on intervertebral disk herniation1, total disk replacement7, anterior spinal surgery8, and thoracolumbar fusion to the pelvis9.

The benefits of non-operative versus operative treatment for patients with spinal stenosis (SPS), and degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS) with regards to sexual function are unknown. Moreover, it is unknown whether or not sexual function is important for patients with spinal pathology and low back pain, including DS and SPS.

This study aims to first determine if sexual function is relevant for patients with SPS and DS and to identify patient characteristics associated with an increased relevance of sexual function. We hypothesize that marital status and age are relevant to sexual function in patients with DS and SPS.

The second specific aim of the study is to determine the impact of operative intervention on sexual function for patients with DS and SPS. We hypothesize that surgical intervention and pain are important predictors of sexual function in patients with DS and SPS.

Materials and Methods

The SPORT study and cohort has been previously described.10 Pre-operative demographics, comorbidities and clinical diagnoses, treatment including non-operative and operative including the number of levels fused was obtained on patients enrolled in the SPORT study. Post-operative and follow up information was also collected, which included a modified version of the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI).

The ODI was developed by Fairbank et al11 to evaluate functional difficulties related to every day activities such as getting dressed, lifting, walking and running, and sleeping. Question number 9 of the modified ODI used in SPORT asks, “In the past week, how has pain affected your sex life?” The response options are 1) My sex life is unchanged; 2) My sex life is unchanged but causes some pain; 3) My sex life is nearly unchanged but it is very painful; 4) My sex life is severely restricted by pain; 5) My sex life is nearly absent because of pain; 6) Pain prevents any sex life at all; 7) Unable to answer or does not apply to me. Patients were asked to complete the ODI upon enrollment (baseline) and at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1, 2, 3, and 4 years of follow up. The response rates for all patients enrolled in the study for each question and response option for the ODI were tabulated. The response rates to question number 9, regarding sexual function were compared to the response rates to the other questions (1–8). Specifically, the number of times the patients left the answer blank or selected response option 7, “Unable to answer or does not apply to me” was calculated. The patients that selected this response or did not respond at all were grouped and classified in to the sexual life not relevant (NR) group. Specifically, relevance in this study is used and is synonymous with “applicability” as stated in the ODI. Patients that responded to question number 9 with response options 1–6 were classified into a sexual life relevant (SLR) group.

Baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures were compared between the NR and SLR groups using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to explore factors influencing sexual life not relevant (NR) after adjusting for other variables in the model. Variables that were significant at p<0.10 were candidates for inclusion in the final multivariable model. Final selection for the model was done using the stepwise method as implemented in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), which sequentially enters the most significant variable with p<0.10 and then after each entered variable removes variables that do not maintain significance at p<0.05. Variables considered for entry into the model were listed in Table 1 except 'ethnicity' and 'listhesis level.' These were excluded because majority of patients are non-hispanic, and 'listhesis level' is only available for DS patients and missing for all SPS patients.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, health status measures, according to whether the patient answered the ODI sex question at baseline.

| Sex Life NOT relevant (n=366) |

Sex-Life Relevant (n=869)* |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 69.7 (10.4) | 63.4 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| Female - no.(%) | 276 (75%) | 385 (44%) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic | 357 (98%) | 835 (96%) | 0.27 |

| Race - White | 310 (85%) | 729 (84%) | 0.79 |

| Education - At least some college | 207 (57%) | 594 (68%) | <0.001 |

| Marital Status - Married | 144 (39%) | 698 (80%) | <0.001 |

| Work Status | <0.001 | ||

| Full or part time | 89 (24%) | 345 (40%) | |

| Disabled | 31 (8%) | 80 (9%) | |

| Retired | 200 (55%) | 353 (41%) | |

| Other | 46 (13%) | 91 (10%) | |

| Compensation - Any | 18 (5%) | 71 (8%) | 0.058 |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD) | 29.3 (5.9) | 29.4 (5.9) | 0.92 |

| Smoker | 32 (9%) | 81 (9%) | 0.83 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 186 (51%) | 377 (43%) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 57 (16%) | 119 (14%) | 0.44 |

| Osteoporosis | 54 (15%) | 75 (9%) | 0.002 |

| Heart Problem | 103 (28%) | 184 (21%) | 0.01 |

| Stomach Problem | 83 (23%) | 189 (22%) | 0.78 |

| Bowel or Intestinal Problem | 44 (12%) | 85 (10%) | 0.28 |

| Depression | 59 (16%) | 109 (13%) | 0.11 |

| Joint Problem | 233 (64%) | 457 (53%) | <0.001 |

| Other | 141 (39%) | 313 (36%) | 0.44 |

| Symptom duration > 6 months | 207 (57%) | 522 (60%) | 0.28 |

| SF-36 scores, mean (SD) | |||

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score | 33.2 (19.5) | 33.5 (19.4) | 0.82 |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score | 31.2 (21.8) | 36 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score | 49.1 (12) | 50 (11.6) | 0.22 |

| Physical Component Summary (PCS) Score | 28.7 (8.5) | 30 (8.5) | 0.016 |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD) | 44.5 (17.7) | 41 (18.3) | 0.002 |

| Sciatica Frequency Index (0–24) (SD) | 13.6 (5.6) | 14 (5.7) | 0.26 |

| Sciatica Bothersome Index (0–24) (SD) | 14.4 (5.6) | 14.5 (5.7) | 0.74 |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness (0–6) (SD) | 4.3 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.8) | 0.17 |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness (0–6) (SD) | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.5 (1.7) | 0.48 |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 255 (70%) | 594 (68%) | 0.70 |

| Problem getting better or worse | 0.31 | ||

| Getting better | 29 (8%) | 55 (6%) | |

| Staying about the same | 108 (30%) | 289 (33%) | |

| Getting worse | 225 (61%) | 514 (59%) | |

| Treatment preference | 0.29 | ||

| Preference for non-surg | 142 (39%) | 322 (37%) | |

| Not sure | 83 (23%) | 175 (20%) | |

| Preference for surgery | 139 (38%) | 372 (43%) | |

| Diagnosis | 0.002 | ||

| SPS | 162 (44%) | 472 (54%) | |

| DS | 204 (56%) | 397 (46%) | |

| Pseudoclaudication - Any | 308 (84%) | 711 (82%) | 0.37 |

| SLR or Femoral Tension | 51 (14%) | 166 (19%) | 0.036 |

| Pain radiation - any | 279 (76%) | 688 (79%) | 0.28 |

| Any Neurological Deficit | 199 (54%) | 477 (55%) | 0.92 |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 97 (27%) | 221 (25%) | 0.75 |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 92 (25%) | 259 (30%) | 0.11 |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 103 (28%) | 220 (25%) | 0.34 |

| Listhesis Level | 0.53 | ||

| L3–L4 | 22 (6%) | 35 (4%) | |

| L4–L5 | 182 (50%) | 362 (42%) | |

| Stenosis Levels | |||

| L2–L3 | 80 (22%) | 152 (17%) | 0.086 |

| L3–L4 | 198 (54%) | 458 (53%) | 0.70 |

| L4–L5 | 352 (96%) | 807 (93%) | 0.037 |

| L5–S1 | 71 (19%) | 159 (18%) | 0.71 |

| Stenotic Levels (Mod/Severe) | 0.06 | ||

| None | 11 (3%) | 27 (3%) | |

| One | 162 (44%) | 442 (51%) | |

| Two | 126 (34%) | 287 (33%) | |

| Three+ | 67 (18%) | 113 (13%) | |

| Stenosis Locations | |||

| Central | 339 (93%) | 753 (87%) | 0.004 |

| Lateral Recess | 315 (86%) | 734 (84%) | 0.53 |

| Neuroforamen | 128 (35%) | 322 (37%) | 0.53 |

| Stenosis Severity | 0.082 | ||

| Mild | 11 (3%) | 27 (3%) | |

| Moderate | 130 (36%) | 367 (42%) | |

| Severe | 225 (61%) | 475 (55%) | |

| Instability | 14 (4%) | 33 (4%) | 0.89 |

In total, 366 SPS/DS had missing ODI sex question at baseline, and 869 answered ODI sex question at baseline. Of the 869 patients, 825 had at least 1 follow-up through 4 years. Forty four patients were excluded as they did not have follow-up data on the sex question, leaving 825 patients in the outcomes study.

The three operative treatment groups (surgery without fusion, one level fusion, and two or more level fusion) were compared to the non-operative group with regards to response to ODI question #9 to determine the impact of surgery on sexual function. Non-operative treatment in this cohort is well described in SPORT trial10. Patients for whom sex-life was not relevant were excluded from this analysis. Baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures of the four treatment groups were compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

Because of the crossover between the non-operative to operative treatment arms, analysis was based on treatments actually received in the combined randomized and observational cohorts. In the as-treated analysis, the treatment indicator was a time-varying covariate, allowing for variable times of surgery. Times are measured from the beginning of treatment, i.e. the time of surgery for the surgical group and the time of enrollment for the non-operative group. Therefore, outcome measures prior to surgery were included in the estimates of the non-operative treatment effect. After surgery, outcome measures were assigned to the surgical group (based on what type of surgery was performed) with follow-up measured from the date of surgery.

Patients that responded with options 2–6 indicated having sex-life related pain. The percentage of patients who reported having sex-life related pain was compared across time and across treatment groups (three operative groups and a non-operative group). In detail, the repeated measures of pain with sex life (having sex-life related pain vs. sex-life unchanged), a binary outcome, were analyzed via a longitudinal model based on generalized estimating equations (GEE) with logit link function. The analysis was adjusted for age, gender, race, diagnosis, marital status, depression, baseline stenosis bothersomeness, and baseline pain with sex life. Outcomes between treatment groups at each time-point were compared using a Wald test. Across the four years of follow-up, overall comparisons of the “area under the curve” between groups were made by using a Wald test. Computation was done using SAS procedure PROC GLIMMIX. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 based on a two-sided hypothesis test with no adjustments made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Relevance of sex life to SPS and DS patients

1235 patients were included to determine relevance of sex life. 366 (29%) of those patients did not answer (n=12) or responded with response option 7, “Unable to answer or does not apply to me” (n=354) were included in the NR group. 869 patients selected choices 1–6 for the sex life question and were included in the SLR group. At baseline, 481 patients (55% of SLR group, 39% of all patients) reported having some level of pain associated with their sex life while 388 (45% of SLR group, 31% of all patients) reported having no pain with their sex-life.

Table 1 shows the results of univariate analysis comparing the SLR and NR groups with regards to baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures. Table 2 shows results from the multivariable model exploring factors influencing the response of Not-Relevant. The SLR group was younger than the NR group (63.4 vs 69.7, p<0.001). Patients that were older, female, unmarried, had 3 or more stenotic levels, and had central stenosis were more likely to be included in the NR group.

Table 2.

Logistic regression for variables predicting Sex life Not-Relevant at baseline (n=1235)

| Variable | β | χ2 | P value | Odds ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −7.1153 | 139.7617 | <.001 | |

| Age | 0.061 | 61.3713 | <.001 | 1.06 (1.05, 1.08) |

| Female vs Male | 1.4484 | 70.2827 | <.001 | 4.26 (3.03, 5.97) |

| Divorced or Widowed or Unmarriedvs | ||||

| Married | 1.6624 | 116.2671 | <.001 | 5.27 (3.9, 7.13) |

| Moderate or severe stenotic levels | ||||

| Three+ vs zero or one | 0.7557 | 10.68 | 0.001 | 2.13 (1.35, 3.35) |

| Two vs zero or one | 0.1448 | 0.6958 | 0.404 | 1.16 (0.82, 1.62) |

| Central stenosis vs No central stenosis | 0.5295 | 3.8549 | 0.05 | 1.7 (1, 2.88) |

| Predictor variables: | ||||

| Variables considered for entry into the model were listed in Table 1: age in years, gender, white race, education, marital status, work status, compensation, Body Mass Index (BMI), smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, osteoporosis, heart problem, stomach problem, bowel or intestinal problem, depression, joint problem, other comorbidities, time since most recent episode, SF-36 Bodily Pain score, Physical Function score, Mental Component Summary score, Physical Component Summary score, Oswestry Disability Index, Stenosis Bothersomeness Index, Back Pain Bothersomeness scale, Leg Pain Bothersomeness scale, satisfication with symptoms, problem getting better or worse, treatment preference, diagnosis, pseudoclaudication, SLR or Femoral tension, pain radiation, any neurological deficit, reflexes, sensory, motor, stenosis levels, moderate/severe stenotic levels, central stenosis, lateral recess location, neuroforamen stenosis, stenosis severity. But 'ethnicity' and 'listhesis level' were excluded because majority of patients are non-hispanic, and 'listhesis level' is only available for DS patients and missing for SPS patients. | ||||

Operative vs non-operative treatment and sex life

Of the 869 patients in the SLR group, 825 had at least 1 follow-up through 4 years. Forty four patients were excluded as they did not have follow-up data on the sex question, leaving 825 patients that were included in the analysis comparing operative versus non-operative treatment. 449 of these patients had SPS while 376 had DS. 294 patients underwent non-operative management. 531 underwent operative management; 270, 192, and 69 patients received decompression alone, one level fusion, or more than one level fusion, respectively.10 Baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health status measures according to treatments received are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, health status measures, according to treatment received*.

| Nonoperative (n=294) |

Surgery no fusion (n=270) |

One level fusion (n=192) |

Two+ levels fusion (n=69) |

p-value | ALL (n=825) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 64.9 (9.8) | 62.1 (12.2) | 61.1 (10) | 64.4 (7.9) | <0.001 | 63.1 (10.7) |

| Female - no.(%) | 125 (43%) | 83 (31%) | 110 (57%) | 40 (58%) | <0.001 | 358 (43%) |

| Ethnicity: Not Hispanic - no. (%)† | 280 (95%) | 260 (96%) | 184 (96%) | 68 (99%) | 0.64 | 792 (96%) |

| Race - White - no. (%) | 237 (81%) | 233 (86%) | 158 (82%) | 64 (93%) | 0.049 | 692 (84%) |

| Education - At least some college - no. (%) | 207 (70%) | 181 (67%) | 137 (71%) | 50 (72%) | 0.69 | 575 (70%) |

| Marital Status - Married - no. (%) | 229 (78%) | 219 (81%) | 163 (85%) | 62 (90%) | 0.064 | 673 (82%) |

| Work Status - no. (%) | 0.23 | |||||

| Full or part time | 120 (41%) | 106 (39%) | 81 (42%) | 31 (45%) | 338 (41%) | |

| Disabled | 26 (9%) | 27 (10%) | 19 (10%) | 4 (6%) | 76 (9%) | |

| Retired | 123 (42%) | 113 (42%) | 63 (33%) | 24 (35%) | 323 (39%) | |

| Other | 25 (9%) | 24 (9%) | 29 (15%) | 10 (14%) | 88 (11%) | |

| Disability compensation - no. (%)‡ | 20 (7%) | 23 (9%) | 20 (10%) | 7 (10%) | 0.52 | 70 (8%) |

| Mean Body Mass Index (BMI), (SD)§ | 29.4 (5.7) | 29.2 (5.4) | 29.7 (7.1) | 28.6 (5.4) | 0.60 | 29.3 (5.9) |

| Smoker - no. (%) | 33 (11%) | 20 (7%) | 17 (9%) | 5 (7%) | 0.42 | 75 (9%) |

| Comorbidities - no. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 132 (45%) | 105 (39%) | 85 (44%) | 29 (42%) | 0.50 | 351 (43%) |

| Diabetes | 46 (16%) | 34 (13%) | 23 (12%) | 8 (12%) | 0.58 | 111 (13%) |

| Osteoporosis | 29 (10%) | 16 (6%) | 19 (10%) | 4 (6%) | 0.24 | 68 (8%) |

| Heart Problem | 70 (24%) | 60 (22%) | 29 (15%) | 13 (19%) | 0.12 | 172 (21%) |

| Stomach Problem | 70 (24%) | 52 (19%) | 48 (25%) | 13 (19%) | 0.37 | 183 (22%) |

| Bowel or Intestinal Problem | 32 (11%) | 27 (10%) | 14 (7%) | 4 (6%) | 0.40 | 77 (9%) |

| Depression | 31 (11%) | 27 (10%) | 39 (20%) | 7 (10%) | 0.004 | 104 (13%) |

| Joint Problem | 163 (55%) | 135 (50%) | 107 (56%) | 30 (43%) | 0.19 | 435 (53%) |

| Otherr¶ | 101 (34%) | 89 (33%) | 83 (43%) | 23 (33%) | 0.11 | 296 (36%) |

| Symptom duration > 6 months - no. (%) | 172 (59%) | 161 (60%) | 121 (63%) | 40 (58%) | 0.77 | 494 (60%) |

| Pain with sex life - no. (%) | 140 (48%) | 158 (59%) | 126 (66%) | 40 (58%) | <0.001 | 464 (56%) |

| SF-36 scores, mean (SD)‖ | ||||||

| Bodily Pain (BP) Score | 39.1 (20.5) | 29.9 (18.2) | 29.9 (17.9) | 33.6 (17.5) | <0.001 | 33.5 (19.4) |

| Physical Functioning (PF) Score | 41.8 (25.3) | 33.7 (22.3) | 32.7 (20.5) | 33.3 (21.1) | <0.001 | 36.3 (23.3) |

| Mental Component Summary (MCS) Score | 51.2 (10.7) | 49.2 (12.1) | 48.7 (11.7) | 52.2 (12) | 0.023 | 50.1 (11.6) |

| Physical Component Summary (PCS) Score | 31.7 (9.4) | 29.3 (8.3) | 28.9 (7.6) | 29.2 (7.6) | <0.001 | 30.1 (8.6) |

| Oswestry (ODI) (SD)** | 34.6 (18.5) | 44.8 (18.5) | 44 (16.2) | 43.2 (17.4) | <0.001 | 40.9 (18.5) |

| Stenosis Frequency Index (0–24)†† | 12.2 (5.6) | 15.1 (5.8) | 15.1 (5.2) | 14.9 (5.5) | <0.001 | 14 (5.7) |

| Stenosis Bothersome Index (0–24)‡‡ | 12.6 (5.7) | 15.4 (5.5) | 15.9 (5.3) | 15.3 (5.5) | <0.001 | 14.5 (5.7) |

| Back Pain Bothersomeness§§ | 3.8 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.9) | 4.5 (1.6) | 4.2 (2) | 0.001 | 4.1 (1.8) |

| Leg Pain Bothersomeness¶¶ | 4 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.8) | <0.001 | 4.4 (1.7) |

| Satisfaction with symptoms - very dissatisfied | 148 (50%) | 210 (78%) | 158 (82%) | 51 (74%) | <0.001 | 567 (69%) |

| Problem getting better or worse - no. (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Getting better | 34 (12%) | 9 (3%) | 9 (5%) | 2 (3%) | 54 (7%) | |

| Staying about the same | 126 (43%) | 80 (30%) | 47 (24%) | 21 (30%) | 274 (33%) | |

| Getting worse | 130 (44%) | 176 (65%) | 135 (70%) | 45 (65%) | 486 (59%) | |

| Treatment preference - no. (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Preference for non-surg | 201 (68%) | 52 (19%) | 35 (18%) | 16 (23%) | 304 (37%) | |

| Not sure | 71 (24%) | 36 (13%) | 44 (23%) | 12 (17%) | 163 (20%) | |

| Preference for surgery | 22 (7%) | 182 (67%) | 113 (59%) | 41 (59%) | 358 (43%) | |

| Diagnosis - no. (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| SPS | 161 (55%) | 257 (95%) | 20 (10%) | 11 (16%) | 449 (54%) | |

| DS | 133 (45%) | 13 (5%) | 172 (90%) | 58 (84%) | 376 (46%) | |

| Pseudoclaudication - Any - no.(%) | 237 (81%) | 212 (79%) | 164 (85%) | 60 (87%) | 0.17 | 673 (82%) |

| SLR or Femoral Tension - no.(%) | 58 (20%) | 58 (21%) | 30 (16%) | 12 (17%) | 0.44 | 158 (19%) |

| Pain radiation - any - no.(%) | 231 (79%) | 214 (79%) | 152 (79%) | 55 (80%) | 1 | 652 (79%) |

| Any Neurological Deficit - no.(%) | 174 (59%) | 143 (53%) | 95 (49%) | 41 (59%) | 0.14 | 453 (55%) |

| Reflexes - Asymmetric Depressed | 77 (26%) | 67 (25%) | 42 (22%) | 22 (32%) | 0.40 | 208 (25%) |

| Sensory - Asymmetric Decrease | 91 (31%) | 85 (31%) | 53 (28%) | 19 (28%) | 0.77 | 248 (30%) |

| Motor - Asymmetric Weakness | 80 (27%) | 70 (26%) | 39 (20%) | 22 (32%) | 0.20 | 211 (26%) |

| Listhesis Level - no.(%) | 0.22 | |||||

| L3–L4 | 10 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 13 (7%) | 9 (13%) | 34 (4%) | |

| L4–L5 | 123 (42%) | 11 (4%) | 159 (83%) | 49 (71%) | 342 (41%) | |

| Stenosis Levels - no.(%) | ||||||

| L2–L3 | 42 (14%) | 76 (28%) | 18 (9%) | 6 (9%) | <0.001 | 142 (17%) |

| L3–L4 | 146 (50%) | 180 (67%) | 71 (37%) | 39 (57%) | <0.001 | 436 (53%) |

| L4–L5 | 272 (93%) | 247 (91%) | 181 (94%) | 68 (99%) | 0.18 | 768 (93%) |

| L5–S1 | 66 (22%) | 56 (21%) | 23 (12%) | 8 (12%) | 0.009 | 153 (19%) |

| Stenotic Levels (Mod/Severe) - no.(%) | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 15 (5%) | 5 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 27 (3%) | |

| One | 151 (51%) | 101 (37%) | 134 (70%) | 32 (46%) | 418 (51%) | |

| Two | 97 (33%) | 105 (39%) | 39 (20%) | 30 (43%) | 271 (33%) | |

| Three+ | 31 (11%) | 59 (22%) | 15 (8%) | 4 (6%) | 109 (13%) | |

| Stenosis Locations - no.(%) | ||||||

| Central | 249 (85%) | 228 (84%) | 171 (89%) | 66 (96%) | 0.049 | 714 (87%) |

| Lateral Recess | 244 (83%) | 222 (82%) | 168 (88%) | 65 (94%) | 0.048 | 699 (85%) |

| Neuroforamen | 119 (40%) | 82 (30%) | 80 (42%) | 28 (41%) | 0.034 | 309 (37%) |

| Stenosis Severity - no.(%) | 0.068 | |||||

| Mild | 15 (5%) | 5 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 27 (3%) | |

| Moderate | 138 (47%) | 112 (41%) | 82 (43%) | 23 (33%) | 355 (43%) | |

| Severe | 141 (48%) | 153 (57%) | 106 (55%) | 43 (62%) | 443 (54%) | |

| Instability - no.(%)*** | 8 (3%) | 1 (0%) | 20 (10%) | 4 (6%) | <0.001 | 33 (4%) |

Total 825 SPORT SPS/DS paitents, who answered ODI sex question at baseline and had at least one follow-up through 4 years, were in the current analysis.

Race or ethnic group was self-assessed. Whites and blacks could be either Hispanic or non-Hispanic.

This category includes patients who were receiving or had applications pending for workers compensation, Social Security compensation, or other compensation.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Other = problems related to stroke, cancer, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol, drug dependency, lung, liver, kidney, blood vessel, nervous system, migraine or anxiety.

The SF-36 scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating less severe symptoms.

The Oswestry Disability Index ranges from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Frequency Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Stenosis Bothersomeness Index ranges from 0 to 24, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Low Back Pain Bothersomness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

The Leg Pain Bothersomeness Scale ranges from 0 to 6, with lower scores indicating less severe symptoms.

Spinal instability is defined as a change of more than 10 degrees of angulation or more than 4 mm of translation of the vertebrae between flexion and extension of the spine.

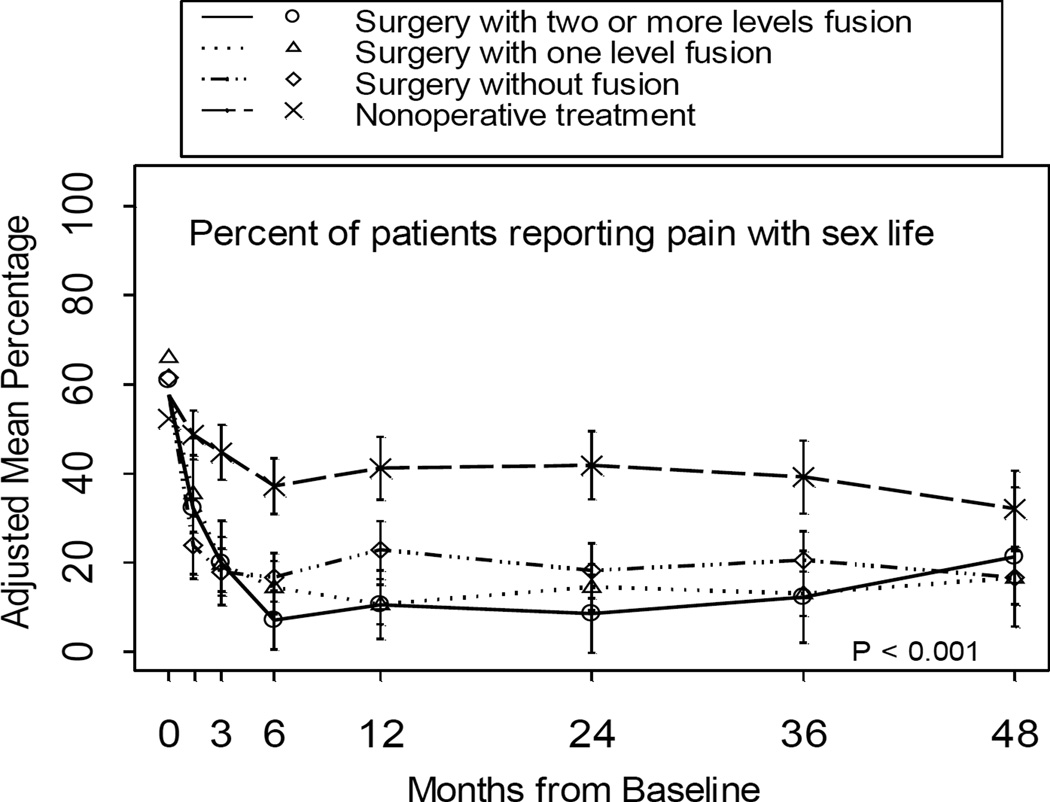

Table 4 and Figure 1 show the percentage of patients in each treatment group reporting pain related to sex-life through 4 years of follow up. The percentage of patients experiencing pain with sex-life was higher for the operative treatment groups (although not statistically different) compared to the non-operative group at baseline. At all follow up time points the three operative groups had a lower percentage of patients reporting pain with their sex life compared to the non-operative group (p<0.05 at all time points except between 2 or more level fusion and non-operative at 4 years of follow up).

Table 4.

Adjusted* mean percent of patients reporting pain with sex life and 95% confidence interval (CI) in parentheses, according to treatment received.

| Percent of patients reporting pain with sex life (%) (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonoperative (n = 531) |

Surgery no fusion (n = 270) |

One level fusion (n = 192) |

Two+ levels fusion (n = 69) |

P Value | |

| 6W | 49 (43, 54) | 24 (18, 31) | 35 (27, 45) | 32 (19, 50) | <0.001 |

| 3M | 45 (39, 51) | 18 (13, 24) | 20 (14, 27) | 20 (12, 31) | <0.001 |

| 6M | 37 (31, 44) | 17 (12, 23) | 14 (9, 22) | 7 (3, 17) | <0.001 |

| 1Y | 41 (34, 48) | 23 (17, 30) | 11 (7, 16) | 11 (5, 21) | <0.001 |

| 2Y | 42 (34, 50) | 18 (13, 25) | 14 (10, 20) | 9 (3, 23) | <0.001 |

| 3Y | 39 (31, 48) | 20 (15, 28) | 13 (9, 19) | 12 (5, 27) | <0.001 |

| 4Y | 32 (24, 41) | 17 (11, 24) | 17 (11, 24) | 21 (9, 41) | 0.007 |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, diagnosis, marital status, depression, baseline stenosis bothersomenesse, and baseline sex life.

Figure 1.

The percentage of patients reporting pain with sex life by treatment group at all follow up time points, up to 4 years of follow up.

* p-value is time weighted average 4 years (area under the curve p-value).

Discussion

This study assessed sex life function responses to patients with SPS and DS using responses to the ODI and if the sex life function question was applicable (relevant) to patients with these conditions. The findings demonstrate that at baseline, sex life was relevant to the majority of patients (71%) and 55% of these (39% of all patients) had at some pain affecting their sex life. This is similar to previously reported rates of pain affecting sex life in patients with low back pain.7–9 Given the high rate of patients whose sex life is affected by pain, it is an appropriate issue for the physician to address with their patient. Prior studies show that only 41% of physicians routinely question patients with lumbar disc herniation about sexual problems.1 One reason for this may be due to the fact that surgeons are unaware of the importance of sex-life for patients. The information presented here suggests that sex-life function is relevant to patients with spinal pathology and should be addressed. The study did identify a subset of patients for which sex-life was less likely to be applicable: patients who were older, female and unmarried and with coexisting joint problems or hypertension.

The impact of operative intervention on improvement in pain related to sexual activity was also assessed. At baseline, the operative groups had a higher percentage of patients with pain related to sexual activity compared to the non-operative control group. Figure 1 shows a drastic treatment effect of surgery by 3 months after surgery and improvement in pain related to sex. The number of patients in operative group reporting pain with sexual activity decreased to below 20% and remained in this range throughout 4 years of follow up. In contrast, approximately 40% of patients in the non-operative group reported having some level of pain with sexual activity throughout the follow up period. These findings are similar to previously published reports. Berg et al showed that sex life improved significantly with a decrease in low back pain after posterior lumbar fusion and total disk replacement.7 Hamilton et al showed that 40% of older patients with thoracolumbar fusion to the pelvis had no or only mild sexual dysfunction.9 In contrast to previously published reports, this is the first study to include a large number of patients and include a non-operative control group.

There are a number of limitations to the study, most notably; pain with sex life was determined using one question from the ODI. The validity of the study would have been improved by using a validated survey that more comprehensively addresses sexual function and is able to assess differences across time. The method of assessing pain also did not account for different severity of pain. Nonetheless, the study does show that fewer patients report having pain related to sexual activity following operative management of DS and SPS compared to non-operative treatment. The duration of the effect may be limited by several factors including development of adjacent level pathology. Further studies are ongoing to better characterize improvements in sexual function and activity following operative treatment for DS and SPS. Another notable limitation is that a secondary analysis of the SPORT data was used and not all patients were tracked at each follow up timepoint. Finally, to determine whether or not sex-life is applicable or not, it was assumed that sex life was not applicable for those that did not respond or selected, “Unable to answer or does not apply to me.” This is a reasonable assumption to make, but the question does not definitively ask patients if they are involved in sexual activity or how important their sex life is and this supports the design of a prospective study to better understand spine related variables affecting this fundamental function of life. Nonetheless, the findings suggest that sex life questions are less applicable for older, female and unmarried patients and patients with coexisting joint problems.

Sex-life is a relevant consideration for 70% of patients enrolled in the SPORT study with DS and SPS. Older, female and unmarried patients and patients with coexisting joint problems or hypertension were more likely to state that sex-life did not apply to them. Compared to the non-operative treatment group, fewer patients in the operative group reported pain related to their sex life. Sex-life is a relevant consideration for the majority of patients with DS and SPS; operative treatment leads to improved sex-life related pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U01-AR45444), the Office of Research on Women's Health, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funds were received in support of this work. The Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center in Musculoskeletal Diseases is funded by NIAMS (P60-AR048094 and P60-AR062799).

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: consultancy, stocks.

References

- 1.Akbas NB, Dalbayrak S, Kulcu DG, Yilmaz M, Yilmaz T, Naderi S. Assessment of sexual dysfunction before and after surgery for lumbar disc herniation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:581–586. doi: 10.3171/2010.5.SPINE09906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maigne JY, Chatellier G. Assessment of sexual activity in patients with back pain compared with patients with neck pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:82–87. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambler N, Williams AC, Hill P, Gunary R, Cratchley G. Sexual difficulties of chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:138–145. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin D. The no--or the yes and the how--of sex for patients with neck, back and radicular pain syndromes. Calif Med. 1970;113:12–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laffosse JM, Tricoire JL, Chiron P, Puget J. Sexual function before and after primary total hip arthroplasty. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinke E, Patterson-Midgley P. Sexual counseling following acute myocardial infarction. Clin Nurs Res. 1996;5:462–472. doi: 10.1177/105477389600500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg S, Fritzell P, Tropp H. Sex life and sexual function in men and women before and after total disc replacement compared with posterior lumbar fusion. Spine J. 2009;9:987–994. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.08.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A Swedish Lumbar Spine Study G. Sexual function in men and women after anterior surgery for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:677–682. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1017-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton DK, Smith JS, Nguyen T, Arlet V, Kasliwal MK, Shaffrey CI. Sexual function in older adults following thoracolumbar to pelvic instrumentation for spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:95–100. doi: 10.3171/2013.4.SPINE121078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunsker SB, Awad IA, McCormick PC. Spine patient outcomes research trial. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:1150–1152. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O'Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.