Abstract

Background

Herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2) may heighten immune activation and increase HIV-1 replication, resulting in greater infectivity and faster HIV-1 disease progression. An 18-week randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial of 500mg valacyclovir twice daily in 20 antiretroviral-naive women co-infected with HSV-2 and HIV-1 was conducted and HSV-2 suppression was found to significantly reduce both HSV-2 and HIV-1 viral loads both systemically and the endocervical compartment.

Methods

To determine the effect of HSV-2 suppression on systemic and genital mucosal inflammation, plasma specimens and endocervical swabs were collected weekly from volunteers in the trial and cryopreserved. Plasma was assessed for concentrations of 31 cytokines and chemokines; endocervical fluid was eluted from swabs and assayed for 14 cytokines and chemokines.

Results

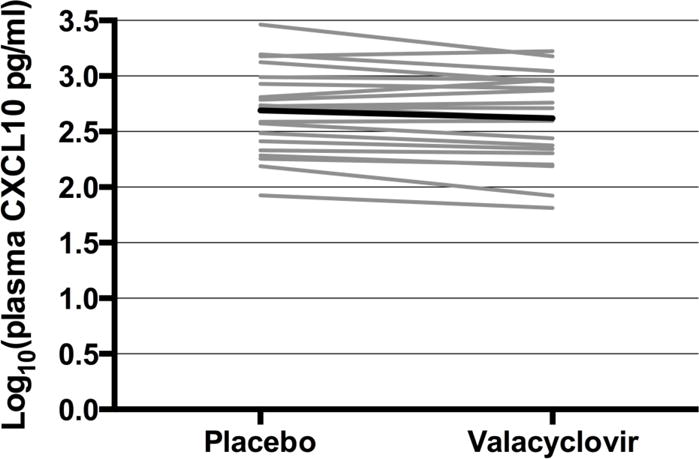

Valacyclovir significantly reduced plasma CXCL10 but did not significantly alter other cytokine concentrations in either compartment.

Conclusions

These data suggest genital tract inflammation in women persists despite HSV-2 suppression, supporting the lack of effect on transmission seen in large scale efficacy trials. alternative therapies are needed to reduce persistent mucosal inflammation that may enhance transmission of HSV-2 and HIV-1.

Keywords: HSV-2, suppressive therapy, inflammation, HIV-1/HSV-2 co-infection

Introduction

HIV-1 infection is characterized by chronic immune activation, including elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The importance of immune activation in HIV-1 pathogenesis has been recognized since early in the epidemic and the mechanisms that drive and sustain this immune activation are an area of active investigation. Chronic and recurrent infections, including herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), may heighten immune activation and increase HIV-1 replication, resulting in greater infectivity and faster HIV-1 disease progression.

HSV-2, the etiologic agent of most genital herpes, is common among persons with HIV-1. The hallmarks of HSV-2 infection are periodic symptomatic genital lesions and frequent asymptomatic viral shedding. HSV-2 infection, although life-long, is treatable with well-tolerated oral antiviral medications, including acyclovir and other antiherpetic thymidine kinase inhibitors. Among HSV-2/HIV-1 co-infected individuals, daily HSV-2 suppressive therapy results in decreased incidence of HSV-2 lesions, asymptomatic genital HSV-2 shedding, and systemic and genital HIV-1 concentrations (1–3). Although the mechanisms by which HSV-2 may stimulate systemic and genital HIV-1 replication are not well understood, HSV-2 infection has been associated with higher genital chemokine levels and increases in numbers of HIV-1 target cells in the genital mucosa, suggesting local immunologic alteration that may increase HIV-1 replication (4, 5).

In 2005, we conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of valacyclovir HSV-2 suppressive therapy to determine the effect of HSV-2 suppression on HIV-1 levels. Twenty HSV-2/HIV-1 co-infected women in Lima, Peru who were not receiving antiretroviral therapy were randomly assigned to either 500mg oral valacyclovir twice daily or matching placebo (6). After 8 weeks, a 2 week washout period occurred and participants then crossed over to the alternative treatment for an additional 8 weeks. We demonstrated that HSV-2 suppression resulted in a 45% decrease in plasma HIV-1 levels and a 55% decrease in cervical HIV-1 levels (6). Given the large reduction in viral levels seen in the trial, in the present study we sought to determine whether this reduction was associated with changes in inflammatory mediators in the trial volunteers. We measured systemic and genital cytokine levels using a multiplex platform and examined their association with HSV-2 suppression and HIV-1 concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Design

The randomized clinical trial of valacyclovir for HSV-2 suppression was conducted between March and December 2005 in Peru (ClinicalTrials.gov registration #NCT00465205). Women were enrolled who were ≥ 18 years of age, HIV-1 and HIV-2 seropositive, had CD4+ T cell counts > 200 cells/μl and were not using anti-retroviral or anti-HSV medications (6). All 20 participants completed the study and median medication adherence was 100%, as assessed by pill counts. The institutional review boards of the University of Washington and the Peruvian Asociación Civil Impacta Salud y Educación approved the protocol. Participants provided written informed consent.

Specimen collection

Plasma and endocervical fluid were collected as previously described (6) and assessed for HIV-1 RNA by a validated TaqMan real-time PCR assay (7)and for HSV-2 DNA levels also by PCR (8). Separate plasma and cervical Dacron swab samples in 500μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were collected weekly for 18 weeks and were stored at −80°C until cytokine assessment.

Screening for genital tract infections included nucleic acid amplification for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis (Aptima, Gen-Probe), rapid plasma reagin and treponema-specific testing (microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum, MHA-TP) for syphilis, and vaginal wet mount for bacterial vaginosis, Trichomonas vaginalis, and candidiasis.

Cytokine extraction

All testing was done in early 2010 at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. After testing several published protocols for cytokine extraction from mucosal swabs, the following protocol was followed: Dacron swabs were thawed on ice and transferred to sterile tubes with 450μl of the PBS in which they had been frozen. Secretions were eluted using extraction buffer described in (9), plus 0.05% sodium azide (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Calbiochem/EMD/Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA). Extraction was carried out by first incubating swabs for 2 hours at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g through a 0.22μm Spin-x filter unit (Corning/Costar/Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). The eluate was stored at 4°C overnight. Swabs were removed from the filter and the remaining volume of fluid that had not passed through was measured and transferred to a new microfuge tube for a second extraction overnight at 4°C. The two extraction volumes were combined and 12.5U/ml benzonase (Novagen, Madison, WI) was added to the samples to reduce any effects of DNA aggregation. Samples were then diluted 1:2 for multiplex cytokine analysis.

Multiplex cytokine analysis

Cytokines were measured using Milliplex MAP Human Cytokine kits (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokines were chosen for measurement by screening a subset of samples collected in the washout period and identifying cytokines present at detectable levels. Plasma samples were analyzed using the high sensitivity kit for the following 13 cytokines: IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12(p70), IL-13, IFN-γ, GM-CSF, and TNF-α; and the panel I regular sensitivity kit for the following 18 cytokines: EGF, Eotaxin, Flt3L, Fractalkine, G-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IL-12p40, IL-15, IL-17, CXCL10 (IP-10), MCP-1, MDC, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, sCD40L, sIL-2Rα, and RANTES. Plasma was diluted 1:100 for RANTES analysis. Endocervical swab samples were analyzed using the panel I regular sensitivity kits for the following 14 cytokines: Flt3L, Fractalkine, GRO, G-CSF, IL-10, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IP-10 (CXCL10), MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, RANTES, and TNF-α. Data were processed using a custom in-house export and QC program in conjunction with the Ruminex software program (10) to obtain average estimated log concentrations and standard error (SE) for each value. Limits of detection were defined by determining first or last point on the standard curve that could be distinguished from the lowest or highest standard, and all values outside the limits were replaced with these values.

Statistical analysis

Cytokines and viral nucleic acid levels were all log10 transformed for analysis. For each compartment, to determine whether treatment with valacyclovir altered plasma or cervical cytokine levels, the difference in level of each cytokine while on valacyclovir or placebo was estimated using a linear mixed model adjusting for period. Similarly, the association between levels of HIV-1 RNA or HSV-2 DNA and cytokine level in the same compartment was estimated using a linear mixed model adjusted for whether the participant was on valacyclovir at that visit. Mixed models included random effects for subject to adjust tests for correlation within person. HIV-1 shedding models also included a random effect for valacyclovir, to adjust for correlation with person, within drug, and the covariance between the two, improving model fit. Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to control the overall false discovery rate (FDR) at 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2.

Results

Twenty HSV-2/HIV-1 co-infected women were enrolled in the crossover trial. The median age was 28 years (range 21 to 47) and the median CD4 count was 372 cells/μL (range 229 to 850). One woman had serologic evidence of syphilis and was treated prior to enrollment; no other genital tract infections were detected. Concomitant with the large reductions in both plasma and cervical HIV-1 levels seen in the trial (45% and 55%, respectively (6)), concentrations of two cytokines in plasma samples and six cytokines in endocervical samples were found to be statistically different during HSV-2 suppressive therapy (Table 1). After FDR adjustment, the modest decrease in plasma levels of CXCL10 on valacyclovir treatment remained statistically significant (mean log10 change in concentration= −0.07, p-value=0.0001). Figure 1 shows mean absolute plasma concentrations of CXCL10 over the 8 week period for each participant while on placebo (mean log10 concentration for all participants = 2.69, or 490 pg/ml) or valacyclovir (mean log10 concentration= 2.62, or 417 pg/ml).

Table 1.

Mean log10 change in endocervical or plasma soluble cytokines with valacyclovir administration.

| Endocervical cytokine | Mean log10 change on valacyclovir | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| RANTES | −0.15 | 0.0338 |

| CXCL10 | −0.14 | 0.0404 |

| Plasma cytokine | Mean log10 change on valacyclovir | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| CXCL10* | −0.07 | 0.0001 |

| Flt3L | −0.09 | 0.0071 |

| MIP-1α | −0.07 | 0.0081 |

| MCP-1 | −0.03 | 0.0215 |

| sIL-2Rα | 0.06 | 0.0368 |

P-values are from mixed models adjusted for study period and with random effect for participant to adjust standard errors for correlation within multiple observations on the same person. They are unadjusted regarding control of false discovery rate.

Only plasma CXCL10 remained statistically significant at p=0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg control of false discovery rate.

Figure 1. Treatment with valacyclovir is associated with lower levels of plasma CXCL10.

Mean log10 plasma CXCL10 concentration for each woman on placebo and valacyclovir treatment (grey lines = individual women; black line = average of all women).

Analytes measured and mean log10 pg/ml concentrations detected while on placebo are listed below for reference.

Endocervical Swabs: Flt3L (0.95), Fractalkine (1.44), G-CSF (2.54), GRO (3.08), IL-10 (0.14), IL-1β (0.32), IL-6 (1.69), IL-8 (2.58), IP-10 (CXCL10, 2.28), MCP-1 (1.78), MIP-1α (1.40), MIP-1β (1.59), RANTES (1.25), TNF-α (0.25).

Plasma: EGF (1.46), Eotaxin (1.44), Flt3L (0.75), Fractalkine (1.17), G-CSF (1.42), GM-CSF (−0.28), GRO (2.93), IFNα2 (1.11), IFN-γ (0.42), IL-10 (1.28), IL-13 (0.25), IL-15 (0.26), IL-17 (0.20), IL-1β (−0.27), IL-2 (0.78), IL-4 (0.51), IL-5 (−0.37), IL-6 (0.35), IL-7 (0.58), IL-8 (0.46), IL-12p40 (0.86), IL-12p70 (−0.09), IP-10 (CXCL10, 1.28), MCP-1 (2.24), MDC (2.88), MIP-1α (0.82), MIP-1β (1.45), RANTES (4.62), TNF-α (0.95), sCD40L (3.37), sIL-2Rα (1.55).

We next sought to determine whether the cytokines detected in the plasma and at the cervix were associated with levels of HIV-1 RNA in the same compartment, or with genital HSV-2 DNA shedding. We did not find that HSV-2 shedding was significantly associated with concentrations of endocervical cytokines, adjusting for valacyclovir treatment (Table 2). Endocervical levels of RANTES, MCP-1, IL-8, MIP-1β and CXCL10 were all significantly positively associated with increased HIV-1 viral loads even after FDR adjustment (Table 3). In contrast, no plasma cytokines showed a significant association with HIV-1 viral loads after FDR adjustment (Table 3).

Table 2.

Cytokine levels in the cervix are not significantly associated with HSV-2 shedding

| Endocervical cytokine | Mean log10 change in cytokine concentration per log10 increase in HSV-2 DNA | P-value a |

|---|---|---|

| RANTES | −0.01 | 0.79 |

| MCP-1 | −0.01 | 0.67 |

| IL-8 | 0.00 | 0.93 |

| MIP-1β | −0.01 | 0.53 |

| CXCL10 | 0.02 | 0.46 |

| MIP-1α | −0.02 | 0.29 |

| TNF-α | 0.00 | 0.84 |

| GRO | 0.00 | 0.96 |

| IL-1β | 0.00 | 0.91 |

| IL-6 | 0.01 | 0.56 |

| FLT3L | 0.00 | 0.89 |

| IL-10 | 0.01 | 0.73 |

| Fractalkine | 0.01 | 0.70 |

| G-CSF | 0.01 | 0.55 |

P-values are from mixed models adjusted for valacyclovir and with random effect for participant and valacyclovir to adjust for correlation with person, within drug, and the covariance between the two, improving model fit. They are unadjusted regarding control of false discovery rate.

Table 3.

Higher levels of cytokines in the cervix are associated with increased HIV-1 RNA concentrations.

| Endocervical cytokinea | Mean log10 change in HIV RNA per log10 increase in cytokine | P-valueb |

|---|---|---|

| RANTES* | 0.25 | 0.0020 |

| MCP-1* | 0.25 | 0.0024 |

| IL-8* | 0.29 | 0.0024 |

| MIP-1β* | 0.29 | 0.0043 |

| CXCL10* | 0.22 | 0.0048 |

| MIP-1α | 0.22 | 0.0179 |

| GRO | 0.18 | 0.0421 |

| Plasma analyte | ||

| TNF-α | 0.17 | 0.0277 |

Cytokines that remained statistically significant at p≤0.05 after Benjamini-Hochberg control of false discovery rate are noted with an asterisk (*).

P-values are from mixed models adjusted for valacyclovir and with random effect for participant and valacyclovir to adjust for correlation with person, within drug, and the covariance between the two, improving model fit. They are unadjusted regarding control of false discovery rate.

Discussion

HIV-1 pathogenesis is characterized by increased systemic and local genital tract inflammation. HSV-2 is a common co-infection in persons with HIV-1 that may also contribute to immune activation. In the present study, we found that HSV-2 suppressive therapy reduced plasma CXCL10 but did not alter levels of inflammatory markers measured at the mucosal surface. Mucosal cytokine elevations, including in CXCL10, were associated with higher concentrations of HIV-1 RNA in concurrently collected genital samples.

CXCL10 is a chemokine secreted by monocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts in response to IFN-γ and expression of plasma CXCL10 correlates with HIV-1 viral load in infected individuals (11, 12). The primary outcome of this crossover trial was the effect of valacyclovir on plasma HIV-1 RNA levels, which were decreased by 45% (0.26 log10) during valacyclovir treatment (6). Thus, the decrease in plasma CXCL10 observed here may be related to the decrease in plasma HIV-1 viral load. Interestingly, although valacyclovir also reduced HSV-2 and HIV-1 shedding at the cervix (6), we were unable to detect a local effect on cytokine production among the cytokines we measured. It is possible that this lack of local effect may be due to the cytokine analysis being performed several years after sample collection at which time some significant degradation may have occurred (13). Nevertheless, our data suggest that inflammatory stimuli persist in the mucosa during valacyclovir therapy, which is consistent with persistent inflammation observed in individuals with HSV-2 lesions who received acyclovir suppression (14). The failure of HSV-2 suppression to reduce HIV-1 acquisition or transmission in three large clinical trials (3, 15, 16) has been hypothesized to be in part a result of persistent inflammation, retaining HIV-1 target cells at lesions and keeping them vulnerable to infection. Our findings are supported by another randomized pilot trial of valacyclovir for attenuating inflammation and immune activation in HIV/HSV-2 co-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy which showed valacyclovir did not decrease systemic immune activation or inflammatory biomarkers (17). That study, however, did not examine the expression of CXCL10. Furthermore, in a similar crossover trial looking at valacyclovir treatment for HSV-2 infected/HIV-1 uninfected women in Canada, valacyclovir treatment did not alter the cytokine milieu of the cervix, nor did it significantly affect the number of cervical CD4+ T cells or dendritic cells (18).

The association of female genital tract cytokines with HIV-1 viral load has been examined in a number of other studies. Notably, Blish et al. also found that cervical, but not plasma, levels of CXCL10 were significantly associated with HIV-1 viral load in a Kenyan population (19). More recently, Herold et al. found that, after adjusting for plasma viral load, HIV-1 genital tract shedding was significantly associated with higher CVL concentrations of RANTES (CCL5), as well as IL-6, IL-1β, and MIP-1α (20).

In summary, these results confirm and provide additional evidence that HSV-2 suppressive therapy has little effect in reducing inflammation in the mucosal environment in HSV-2/HIV-1 co-infected Peruvian women. Antiretroviral treatment is inarguably the optimal strategy to reduce HIV-1 levels and HIV-1 morbidity and infectiousness. For persons who are not on antiretroviral therapy, primary prevention of HSV-2 and alternate strategies to reduce levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mucosal inflammation that may contribute to viral spread could be evaluated.

Summary.

HSV-2 suppression was associated with reduced plasma CXCL10 but not genital cytokine levels, suggesting an inflammatory milieu persists in the genital tract despite the reduction in viral burden during treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nadia Andreeva (Fred Hutch), Joan Dragavon and Soccoro Harb (UW Clinical Retrovirology Laboratory) for their assistance with experimental work, Youyi Fong (Fred Hutch) for statistical advice, and Ken Rosenthal (McMaster University) and Steve Voght (Fred Hutch) for editing of this manuscript.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Puget Sound Partners for Global Health. The clinical trial from which the samples for this study were derived was supposed by an investigator-initiated research grant from GlaxoSmithKline [research grant number R 103] and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program under award number P30AI027757 which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA, NIGMS, NIDDK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data from this manuscript was presented at the 17th International Congress of Mucosal Immunology (ICMI) meeting in Berlin on July 17th, 2015.

References

- 1.Barnabas RV, Celum C. Infectious co-factors in HIV-1 transmission herpes simplex virus type-2 and HIV-1: new insights and interventions. Curr HIV Res. 2012;10(3):228–37. doi: 10.2174/157016212800618156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagot N, Ouedraogo A, Foulongne V, et al. Reduction of HIV-1 RNA levels with therapy to suppress herpes simplex virus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):790–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celum C, Wald A, Lingappa JR, et al. Acyclovir and transmission of HIV-1 from persons infected with HIV-1 and HSV-2. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):427–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebbapragada A, Wachihi C, Pettengell C, et al. Negative mucosal synergy between Herpes simplex type 2 and HIV in the female genital tract. AIDS. 2007;21(5):589–98. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masson L, Mlisana K, Little F, et al. Defining genital tract cytokine signatures of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis in women at high risk of HIV infection: a cross-sectional study. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90(8):580–7. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeten JM, Strick LB, Lucchetti A, et al. Herpes simplex virus (HSV)-suppressive therapy decreases plasma and genital HIV-1 levels in HSV-2/HIV-1 coinfected women: a randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(12):1804–8. doi: 10.1086/593214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuckerman RA, Lucchetti A, Whittington WL, et al. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) suppression with valacyclovir reduces rectal and blood plasma HIV-1 levels in HIV-1/HSV-2-seropositive men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(10):1500–8. doi: 10.1086/522523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerome KR, Huang ML, Wald A, Selke S, Corey L. Quantitative stability of DNA after extended storage of clinical specimens as determined by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(7):2609–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2609-2611.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieberman JA, Moscicki AB, Sumerel JL, Ma Y, Scott ME. Determination of cytokine protein levels in cervical mucus samples from young women by a multiplex immunoassay method and assessment of correlates. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15(1):49–54. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defawe OD, Fong Y, Vasilyeva E, et al. Optimization and qualification of a multiplex bead array to assess cytokine and chemokine production by vaccine-specific cells. J Immunol Methods. 2012;382(1–2):117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts L, Passmore JA, Williamson C, et al. Plasma cytokine levels during acute HIV-1 infection predict HIV disease progression. AIDS. 2010;24(6):819–31. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283367836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahle EM, Bolton M, Hughes JP, et al. Plasma cytokine levels and risk of HIV type 1 (HIV-1) transmission and acquisition: a nested case-control study among HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(9):1451–60. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Jager W, Bourcier K, Rijkers GT, Prakken BJ, Seyfert-Margolis V. Prerequisites for cytokine measurements in clinical trials with multiplex immunoassays. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu J, Hladik F, Woodward A, et al. Persistence of HIV-1 receptor-positive cells after HSV-2 reactivation is a potential mechanism for increased HIV-1 acquisition. Nat Med. 2009;15(8):886–92. doi: 10.1038/nm.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celum C, Wald A, Hughes J, et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9630):2109–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, et al. Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1560–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi TJ, Walmsley S, Szadkowski L, et al. A randomized controlled pilot trial of valacyclovir for attenuating inflammation and immune activation in HIV/herpes simplex virus 2-coinfected adults on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(9):1331–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yi TJ, Shannon B, Chieza L, et al. Valacyclovir therapy does not reverse herpes-associated alterations in cervical immunology: a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(5):708–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blish CA, McClelland RS, Richardson BA, et al. Genital Inflammation Predicts HIV-1 Shedding Independent of Plasma Viral Load and Systemic Inflammation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):436–40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826c2edd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold BC, Keller MJ, Shi Q, et al. Plasma and mucosal HIV viral loads are associated with genital tract inflammation in HIV-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(4):485–93. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182961cfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]