Abstract

Purpose

To identify risk factors for intestinal metaplasia in a southeastern Chinese population.

Methods

Subjects who underwent upper GI endoscopy and endoscopic biopsy in the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from 2008 to 2013 were included into this study. Various demographic, geographic, clinical and pathological data were analyzed separately to identify risk factors for intestinal metaplasia.

Results

The incidence of intestinal metaplasia differed significantly in 17 municipal areas ranging from 16.79 to 38.56% and was positively correlated with the age range of 40–70 years, male gender, gastric ulcer, bile reflux, Helicobacter pylori infection, atrophic gastritis, dysplasia, gastric cancer, degree of chronic and acute inflammation, and gross domestic product per capita (P < 0.01). Multivariate linear regression analysis indicated that only gross domestic product per capita revealed a significant difference in the incidence of intestinal metaplasia among all factors mentioned.

Conclusion

This study confirms age, male gender, gastric ulcer, bile reflux, H. pylori infection, severe degree of chronic and acute inflammation to be the risk factors for intestinal metaplasia. We speculate that the gross domestic product per capita of different areas may be a potential independent risk factor impacting the incidence of intestinal metaplasia.

Keywords: Intestinal metaplasia, Risk factors, Helicobacter pylori infection, Inflammation, Gross domestic product per capita

Introduction

Intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the gastric mucosa is characterized by the transformation of the normal gastric epithelium and gastric glands into intestinal epithelium and intestinal glands, and is considered an important precursor to gastric cancer. Patients with histologically confirmed gastric intestinal metaplasia have an up to sixfold increased risk of developing gastric cancer as compared to the population at large (Gomez and Wang 2014). Gastric cancer represents the fifth most common cancer type worldwide, and it is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality (Ferlay et al. 2015). The most recognized theory used to explain the association between IM and gastric cancer (GC) is Correa’s theory. This theory indicates that IM is the precancerous lesion of GC. Shichijo et al. (2016) discovered that endoscopic atrophic gastritis and IM remain prominent risk factors for GC after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Hence, it is important to identify risk factors for the development of IM, in order to predict, diagnose and prevent GC.

With an estimated number of 900,000–950,000 new cases per year at the beginning of the twenty-first century, GC is in fourth place behind cancers of the lung, breast, colon and rectum. In addition, due to its poor prognosis, GC has become the second most common cause of death from cancer and accounts for 700,000 deaths annually (Milosavljevic et al. 2014).

Although the occurrence of GC has decreased in recent years, China remains a high-risk area. During 1991–2000, the age-standardized mortality rate for GC in China was 48.6 per 100,000 person-years, which is three times higher than the global average rate (He et al. 2005; Jemal et al. 2011). Yangzhong City of Jiangsu Province is a high-risk area for GC with a standardized incidence rate of 112.66 per 100,000 person-years and a GC mortality rate of 90.25 per 100,000 person-years (Sheng et al. 2000). Therefore, the screening of high-risk individuals in this region would help in the early detection and prevention of GC. In order to diagnose GC as early as possible, we systematically investigated the incidence rate, geographical distribution and risk factors for IM in China, as well as the correlations between IM, inflammation and H. pylori infection. This may help us monitor its occurrence, obtain early diagnosis and therapy of GC and follow up on this high-risk population of GC.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. As specifically approved by the ethics committee, informed consent was not required for this study, since data were analyzed anonymously. However, all participants signed a written informed consent for upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy before undergoing the procedure.

Materials

The present study retrospectively analyzed data of subjects from Jiangsu and Anhui provinces, who underwent upper GI endoscopy and endoscopic biopsy in the Digestive Endoscopy Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from 2008 to 2013. All records of upper GI endoscopic results were retrieved from the Endoscopy Information System (EIS; Angelwin, Beijing, China) in the Digestive Endoscopy Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. In cases where multiple endoscopies were performed for the same patient, only the initial report was included in the analysis. The demographic data, images of endoscopic examinations, endoscopic and pathological findings, and results of rapid urease test were all available from EIS. Perl programming language was used for data processing.

Endoscopy

All patients underwent conventional upper GI endoscopy using a standard forward-viewing video gastroscope (GIF 240/260, Olympus Optical, Japan). Patients received topical pharyngeal anesthesia or general anesthesia during the procedure. The procedures were performed by experienced senior endoscopists of the Department of Gastroenterology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The upper GI tract (esophagus, stomach and duodenum) was carefully examined. Histological examinations were performed by expert GI pathologists of the Department of Pathology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. IM was diagnosed if it was found in at least one biopsy, irrespective of the site.

Duodenal ulcer (DU), gastric ulcer (GU) and bile reflux were diagnosed by endoscopy. DU and GU were endoscopically defined as a mucosal break ≥5 mm in diameter. Bile reflux was considered to be present when abundant biliary content was found in the stomach and the gastric mucosa was stained with bile (Li et al. 2008).

Diagnosis of H. pylori infection and histological assessment

Rapid urease test (performed using the Rapid urease test kit; SanQiang/HPUT-H102, Fujian, China) was used for detecting H. pylori infection. Rapid urease test has sensitivity of 99% and specificity of 100% when used alone for diagnosis of H. pylori infection (Wong et al. 2001). A single biopsy was obtained for rapid urease test from either the greater or lesser curvature of the antrum, which was approximately 3 cm away from the pylorus. Biopsy samples were obtained from endoscopically detected focal or suspected lesion as targeted biopsy. For nontargeted biopsy studies, biopsies were taken routinely from the greater or lesser curvatures of the antrum or both, based on the revised Sydney system (Dixon et al. 1996) and the fact that gastritis is more frequent in the antrum of the stomach in the Chinese population (Liu et al. 2014). Biopsy specimens were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The slide sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The degree of activity of histologically chronic gastritis was based on the degree of mononuclear cell infiltration and lymphoid follicle number, as determined by the pathologists, and acute inflammation was based on the degree of neutrophilic infiltration. IM was recognized morphologically by the presence of goblet cells, absorptive cells and cells resembling colonocytes. Atrophy was recognized by the loss of appropriate glands. Dysplasia was identified by epithelial disarray and an increased nuclear cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio. In case of disagreement with the pathological diagnosis, a third expert GI pathologist was consulted. The following items were assessed according to the updated Sydney classification system: chronic and acute inflammation, gastric glandular atrophy and IM. All items were assigned scores from 0 (absent) to 1 (mild), 2 (moderate) or 3 (marked) (Stolte and Meining 2001). The Vienna classification was used for the assessment of neoplasia (Schlemper et al. 2000). Gastric appearance and histological results were both used for the diagnosis of gastritis, IM and GC.

Statistical analysis

SAS 9.2 software was used for statistical analysis. Odds ratio (OR), X 2 test and t test were carried out to examine the correlations of IM status with H. pylori infection, AG, dysplasia, age, gender, geographical distribution, chronic inflammatory severity, degree of acute inflammation and lymphoid follicle number. The Cochran–Armitage trend test of IM was also carried out. Linear correlation and multivariate regression were used to analyze the relationship of IM with other geographical factors (significant at the 0.1500 level in the regression model). All calculated P values were two-tailed, and a value <0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

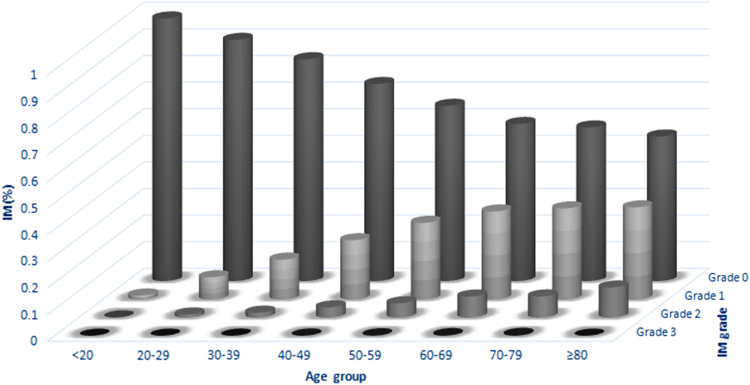

This study included a total of 28,745 upper GI endoscopies performed from 2008 to 2013 in our endoscopy center, with an average biopsy number of 3.32 ± 1.29 (from 2 to 10) in every case. The mean age was 50.98 ± 13.33 years, and the male-to-female ratio was nearly 1:1 (14,625–14,120). The patients were grouped into eight groups based on their age: <20, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and ≥80 years, respectively. The total incidence of IM was 29.64%, which was predominantly present in 40- to 70-year-old patients (Table 1). Differences in IM incidence among the age groups were significant (P < 0.01). The Cochran–Armitage test revealed that not only the incidence rate but also the degree of severity of IM increased notably with age (Fig. 1). In the male population, the incidence rate of IM (30.84%) was higher compared with the female population (28.21%, OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.07–1.18, P < 0.01), and the degree of severity of IM in male patients tended to be more severe than in female patients (P < 0.01). The incidence of GU, DU, bile reflux, H. pylori infection, AG, dysplasia and GC in this study was 4.21, 6.88, 7.48, 26.52, 8.54, 5.81 and 1.50%, respectively. While the incidence rate of IM in GU, DU, bile reflux, H. pylori infection, AG, dysplasia and GC was 5.58, 4.73, 7.77, 27.56, 27.97, 11.76 and 2.18%, respectively (Table 1). All of these factors were positively correlated with the incidence of IM (P < 0.01), except for DU, which was inversely correlated with IM (P < 0.01). In particular, AG exhibited an extremely high positive correlation with IM, with the IM incidence rate of 97.07% in cases with AG versus 23.34% in cases without AG (OR 108.69, 95% CI 85.82–137.64, P < 0.01). Based on the OR, cases were ranked as follows: dysplasia, GC, GU, H. pylori infection and bile reflux (Table 1). Furthermore, the Cochran–Armitage test indicated that all the patients with GU, H. pylori infection, AG, dysplasia and GC were positively correlated with increasing IM grade (all, P < 0.01), while bile reflux may not be significantly correlated with IM (P = 0.01). On the contrary, there was lower IM grade in patients with DU compared with patients without DU (P < 0.01, Table 2).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | With IM (n = 8520) | Without IM (n = 20,225) | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | ||||

| Age (mean ± SD), (years) | 55.38 ± 11.89 | 49.13 ± 13.48 | <0.01 | ||||

| <20 | 3 | 0.04 | 216 | 1.07 | |||

| 20–29 | 136 | 1.60 | 1328 | 6.57 | |||

| 30–39 | 681 | 7.99 | 3460 | 17.11 | |||

| 40–49 | 1836 | 21.55 | 5341 | 26.41 | |||

| 50–59 | 2654 | 31.15 | 5279 | 26.10 | |||

| 60–69 | 2157 | 25.32 | 3160 | 15.62 | |||

| 70–79 | 936 | 10.99 | 1300 | 6.43 | |||

| ≥80 | 117 | 1.37 | 141 | 0.70 | |||

| Gender | 1.12 | 1.07–1.18 | <0.01 | ||||

| Male | 4511 | 52.95 | 10,114 | 50.01 | |||

| Female | 4009 | 47.05 | 10,111 | 49.99 | |||

| Gastric ulcer | 1.79 | 1.58–2.02 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 475 | 5.58 | 635 | 3.14 | |||

| Duodenal ulcer | 0.66 | 0.59–0.74 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 403 | 4.73 | 1466 | 7.25 | |||

| Bile reflux | 1.06 | 0.96–1.17 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 662 | 7.77 | 1489 | 7.36 | |||

| H. pylori | 1.08 | 1.02–1.14 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 2348 | 27.56 | 5276 | 26.09 | |||

| Atrophic gastritis | 108.69 | 85.82–137.64 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 2383 | 27.97 | 72 | 0.36 | |||

| Dysplasia | 3.90 | 3.52–4.31 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 1002 | 11.76 | 669 | 3.31 | |||

| Gastric cancer | 1.81 | 1.50–2.20 | <0.01 | ||||

| Positive | 186 | 2.18 | 246 | 1.22 | |||

Fig. 1.

Trends of the grade of IM in different age groups

Table 2.

Statistics of risk factors based on intestinal metaplasia scores

| Characteristics | Absent (0) | Mild (1) | Moderate (2) | Severe (3) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| <20 | 216 | 1.08 | 3 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | <0.01 |

| 20–30 | 1327 | 6.60 | 121 | 1.68 | 16 | 1.14 | 0 | 0.00 | <0.01 |

| 30–40 | 3450 | 17.17 | 616 | 8.54 | 74 | 5.26 | 1 | 2.86 | <0.01 |

| 40–50 | 5312 | 26.44 | 1589 | 22.04 | 272 | 19.35 | 4 | 11.43 | <0.01 |

| 50–60 | 5222 | 25.99 | 2277 | 31.58 | 422 | 30.01 | 12 | 34.29 | <0.01 |

| 60–70 | 3316 | 15.61 | 1753 | 24.31 | 417 | 29.66 | 11 | 31.43 | <0.01 |

| 70–80 | 1290 | 6.42 | 763 | 10.58 | 176 | 12.52 | 7 | 20.00 | <0.01 |

| ≥80 | 140 | 0.70 | 89 | 1.23 | 29 | 2.06 | 0 | 2.06 | <0.01 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 10,027 | 49.90 | 3776 | 52.36 | 801 | 56.97 | 21 | 60.00 | |

| Female | 10,066 | 50.10 | 3435 | 47.64 | 605 | 43.03 | 14 | 40.00 | <0.01 |

| Gastric ulcer | |||||||||

| Positive | 614 | 3.35 | 410 | 6.13 | 83 | 6.25 | 3 | 9.38 | <0.01 |

| Duodenal ulcer | |||||||||

| Positive | 1457 | 7.59 | 372 | 5.59 | 40 | 3.12 | 0 | 0.00 | <0.01 |

| Bile reflux | |||||||||

| Positive | 1476 | 7.35 | 535 | 7.42 | 133 | 9.46 | 7 | 20.00 | =0.01 |

| H. pylori | |||||||||

| Positive | 5224 | 26.00 | 2049 | 28.41 | 342 | 24.32 | 9 | 25.71 | <0.01 |

| Atrophic gastritis | |||||||||

| None | 19,999 | 99.53 | 5617 | 77.89 | 442 | 31.44 | 9 | 25.71 | |

| Mild | 65 | 0.32 | 1124 | 15.59 | 380 | 27.03 | 13 | 37.14 | <0.01 |

| Moderate | 26 | 0.13 | 431 | 5.98 | 568 | 40.40 | 8 | 22.86 | <0.01 |

| Severe | 3 | 0.01 | 39 | 0.54 | 16 | 1.14 | 5 | 14.29 | <0.01 |

| Dysplasia | |||||||||

| None | 19,448 | 96.80 | 6387 | 88.57 | 1191 | 84.71 | 29 | 82.86 | |

| Mild | 506 | 2.51 | 710 | 9.85 | 191 | 13.58 | 6 | 17.14 | <0.01 |

| Severe | 139 | 0.69 | 114 | 1.58 | 24 | 1.71 | 0 | 0.00 | <0.01 |

| Gastric cancer | |||||||||

| Positive | 244 | 1.21 | 151 | 2.09 | 34 | 2.42 | 3 | 8.57 | <0.01 |

H. pylori infection, inflammation and IM

Among 28,745 cases, patients with both H. pylori infection and inflammation (represented by chronic inflammation score, acute inflammation score and lymphoid follicle number) were employed separately to evaluate the relation between IM, H. pylori infection and inflammation.

As shown in Table 3, patients with H. pylori infection had more severe degree of inflammation than H. pylori negative patients and differences between two groups were observed in all three indices (P < 0.01). Comparing patients with and without IM, the differences in severity of both chronic and acute inflammation, as well as lymphoid follicle number, were all statistically significant (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Correlation between H. pylori infection, intestinal metaplasia and inflammation

| Groups | n | Score-CI (P value) | Score-AI (P value) | L-number (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | ||||

| IM | ||||

| Positive | 6137 | 1.5070 (<.01) | 0.6606 (<.01) | 0.5307 (<0.01) |

| Negative | 20,153 | 1.4229 | 0.4963 | 0.4602 |

| H. pylori | ||||

| Positive | 6972 | 1.8134 (<.01) | 1.1749 (<.01) | 0.8647 (<0.01) |

| Negative | 19,318 | 1.3086 | 0.3036 | 0.3367 |

| (b) | ||||

| IM(+)H. pylori(+) | 1721 | 1.8191 (P1 < 0.01) | 1.2370 (P1 < 0.01) | 0.8749 (P1 < 0.01) |

| IM(+)H. pylori(−) | 4416 | 1.3853 (P2 < 0.01) | 0.4360 (P2 < 0.01) | 0.3966 (P2 < 0.01) |

| IM(−)H. pylori(+) | 5251 | 1.8115 (P3 = 0.53) | 1.1546 (P3 < 0.01) | 0.8614 (P3 = 0.63) |

| IM(−)H. pylori(−) | 14,902 | 1.2859 (P4 < 0.01) | 0.2644 (P4 < 0.01) | 0.3189 (P4 < 0.01) |

P1 P value of comparison between IM(+)H. pylori(+) and IM(+)H. pylori(−); P2 P value of comparison between IM(+)H. pylori(−) and IM(−)H. pylori(−); P3 P value of comparison between IM(−)H. pylori(+) and IM(+)H. pylori(+); P4 P value of comparison between IM(−)H. pylori(−) and IM(−)H. pylori(+)

Score-CI score of chronic inflammation, Score-AI score of acute inflammation, L-number number of lymphoid follicle

Further, we separated patients into four groups according to the status of H. pylori infection and IM (shown in Table 3). The patients with both IM and H. pylori infection had highest chronic inflammation scores, acute inflammation scores and lymphoid follicle number; the double negative group had the lowest scores on all three evaluations. Irrespective of the H. pylori status of the patients, the IM positive group showed a much higher degree of inflammation based on all three scores (P < 0.01). Among patients with IM, the differences in inflammation between H. pylori infection positive and negative groups were significant both in chronic inflammation and in lymphoid follicle number scores (P < 0.01). However, in the H. pylori positive group, the differences of degree of inflammation in patients with and without IM were not significant (P > 0.01). At our endoscopy center, all biopsies were diagnosed with at least mild inflammation (score 1); thus, the difference of average inflammation score between H. pylori positive and negative group was very significant (1.81 vs. 1.31). These results illustrated that inflammation of gastric mucosa was predominantly caused by H. pylori infection, while IM also correlated with the severity of inflammation.

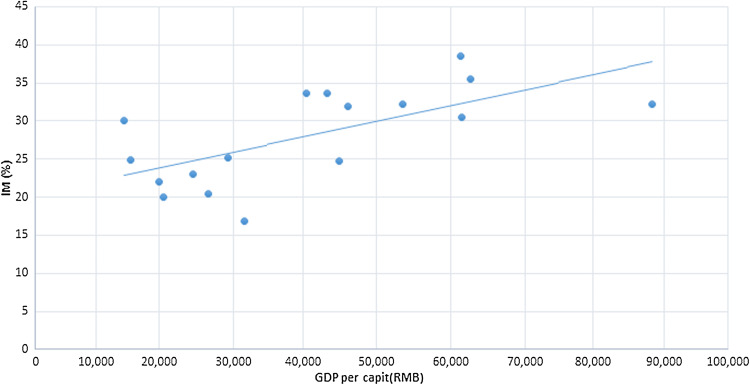

Geographical distribution

The subjects included in this study resided in 17 municipal areas of Jiangsu and Anhui provinces, covering a very large area in southeast China with a combined population of 91.6 million within an area of 146,000 km2. The geographical distribution of 28,745 cases from these areas was collected, including mean age (from 47.53 to 52.13 years), sex rate (from 45.80 to 62.86%), H. pylori infection rate (from 17.50 to 28.10%), degree of inflammation (e.g., mean CI score: from 1.34 to 1.47) and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (Table 4). Among these 17 municipal areas, Xuzhou City recorded the lowest incidence rate of IM (16.79%), while Zhenjiang City scored the highest incidence rate of IM (38.56%), with the corresponding GDP per capita of RMB 31,489 and RMB 61,302, respectively (data sources: Global CNKI, http://tongji.cnki.net/kns55/index.aspx; GDP per capita is the average between 2008 and 2011). Based on linear correlation analysis, we found that the incidence of IM had a remarkable correlation with GDP per capita in the 17 municipal areas (r = 0.66, P = 0.0039; Fig. 2). Nevertheless, no significant relationship existed between IM and biopsy number, mean age, sex rate, H. pylori infection rate, mean acute and chronic inflammation severity and lymphoid follicle numbers (all, P > 0.01). The multivariate linear regression model was used to analyze the relationships between IM and GDP per capita and other risk factors in geographical distributions, and suggested that the GDP per capita of the 17 municipal areas was the only variable found to be significant in this model at a P value of 0.015.

Table 4.

Risk factors for intestinal metaplasia in the 17 prefecture-level cities

| Province | City | IM (%) | Mean age (years) | Sex (male/all %) | Mean total biopsy number | H. pylori infection rate (%) | Mean Score-AI | Mean Score-CI | Mean L-number | GDP per capita (10,000RMB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangsu | Xuzhou | 16.79 | 49.66 | 45.80 | 3.19 | 25.19 | 0.47 | 1.44 | 0.56 | 31,489 |

| Suqian | 20.00 | 49.89 | 62.86 | 3.35 | 17.50 | 0.35 | 1.36 | 0.37 | 20,547 | |

| Huaian | 20.43 | 49.91 | 53.87 | 3.25 | 20.18 | 0.36 | 1.37 | 0.37 | 26,641 | |

| Lianyungang | 23.02 | 49.81 | 50.79 | 3.29 | 21.43 | 0.33 | 1.34 | 0.34 | 24,457 | |

| Yancheng | 25.17 | 51.23 | 56.05 | 3.28 | 26.56 | 0.44 | 1.40 | 0.43 | 29,188 | |

| Taizhou | 33.67 | 51.44 | 56.78 | 3.25 | 23.87 | 0.40 | 1.42 | 0.41 | 40,492 | |

| Yangzhou | 31.97 | 51.29 | 56.97 | 3.31 | 23.32 | 0.49 | 1.46 | 0.38 | 46,120 | |

| Wuxi | 32.26 | 52.13 | 52.42 | 3.40 | 22.58 | 0.43 | 1.40 | 0.36 | 88,341 | |

| Nantong | 24.70 | 50.78 | 57.23 | 3.27 | 24.10 | 0.46 | 1.43 | 0.32 | 44,869 | |

| Nanjing | 30.52 | 51.25 | 49.71 | 3.34 | 28.10 | 0.51 | 1.46 | 0.45 | 61,460 | |

| Zhenjiang | 38.56 | 51.25 | 53.73 | 3.35 | 25.00 | 0.49 | 1.45 | 0.43 | 61,302 | |

| Changzhou | 35.49 | 50.89 | 53.24 | 3.34 | 27.97 | 0.56 | 1.47 | 0.42 | 62,587 | |

| Anhui | Chuzhou | 24.83 | 49.70 | 53.10 | 3.21 | 19.72 | 0.38 | 1.39 | 0.35 | 16,156 |

| Hefei | 33.61 | 50.88 | 59.84 | 3.54 | 23.77 | 0.51 | 1.45 | 0.40 | 43,276 | |

| Chaohu | 30.10 | 49.86 | 49.87 | 3.24 | 24.03 | 0.47 | 1.43 | 0.36 | 15,240 | |

| Xuancheng | 22.05 | 47.53 | 51.18 | 3.21 | 25.20 | 0.48 | 1.47 | 0.41 | 20,003 | |

| Ma-anshan | 32.25 | 49.03 | 50.49 | 3.29 | 18.89 | 0.42 | 1.40 | 0.43 | 53,495 | |

| r | 1.00 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.66 | |

| P value | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.85 | <0.01 |

Fig. 2.

Scatter plot and fitting straight line of the linear correlation analysis of the relationship between IM and GDP per capita

Discussion

This study involved an unprecedented population size, and the large sample size offered sufficient statistical power not only to validate the conclusions of previous studies but also to reveal new findings. In the present study, the reported factors that had a positive correlation with IM incidence were validated such as age, gender, GU, bile reflux, H. pylori infection, AG, dysplasia, GC, inflammation and GDP per capita, which were especially related to GC (den Hoed et al. 2011; Felley et al. 2012; Park and Kim 2015). For instance, de Vries and coworkers reported that risk factors for IM included age, smoking, overweight, drinking, H. pylori infection and bile reflux (de Vries et al. 2008). Another study revealed that in smokers infected with high-virulence H. pylori strains, the risk of IM was further increased (Peleteiro et al. 2007). Some researchers noted that risk factors associated with the presence of IM in outpatients without significant gastroduodenal disease were found at the age of ≥50 years, bile reflux and a history of alcohol drinking, but not for H. pylori infection (Chacaltana Mendoza et al. 2012). Our study included most of the IM-related diseases and their pathological changes, comprehensively reflecting the actual status of IM in these regions.

The impact of age on IM indicates that the older the patients were, the higher the incidence rate of IM was and the greater the degree of IM. This finding was consistent with that of previous studies on IM, AG and dysplasia (de Vries et al. 2008; Sakitani et al. 2011). Furthermore, studies have indicated a variety of known and unknown harmful factors that mediate H. pylori infection, increase cumulatively with age and lead to the appearance and aggravation of IM (Park and Kim 2015). Nevertheless, it was obvious that IM was not just age-related, as the peak age ranged between 40 and 70 years. However, it is possible that older people with intestinal metaplasia could have died due to gastric cancer while the subjects free of intestinal metaplasia survived. Simultaneously, the male population were more frequently affected with IM in our study, revealing that the male gender was an independent risk factor for IM, such as for GC (de Vries et al. 2008; Sakitani et al. 2011), although some reports have found no significant correlations between gender and IM, AG or dysplasia (den Hoed et al. 2011).

We realized that the incidence of IM directly correlated with the incidence of GU, but inversely correlated with the incidence of DU, which was consistent with the findings of Hwang et al., but contrary to the observations of Ye et al. (Hwang et al. 2015; Ye et al. 2009). IM and GU result from the chronic and persistent inflammation of the gastric mucosa, which explains the positive correlation between these diseases. However, the inverse correlation between the incidence of IM and DU is difficult to explain and needs further evaluation. Our results demonstrated higher detection rates of IM in patients with AG, dysplasia and GC, and this was consistent with Correa’s theory on intestinal-type GC (Correa et al. 1975; Kuipers 1997). Reddy and coworkers (Leung et al. 2000) recognized that approximately 2.7% of patients with IM listed in a US Integrated Healthcare System were diagnosed with GC, of which almost 70% of GC cases were detected at the time of IM diagnosis. However, the incidence of IM was high in endoscopically diagnosed GC, which had nontumor pathological data. It also revealed the correlation between GC and IM (Gonzalez et al. 2010). Therefore, IM is a very important indicator of GC in high gastric cancer risk regions.

As a potential risk factor for IM, bile reflux has been rarely mentioned in the previous literature. Bile reflux causes persistent damage to the gastric mucosa, which aggravates IM (Matsuhisa and Tsukui 2012). In our study, it not only revealed a positive relation with the incidence of IM, but also suggested that with the increase in the degree of IM, the percentage of patients with bile reflux increased as well, confirming the foregoing observations. This study indicated that inflammation of gastric mucosa was predominantly caused by H. pylori infection, and IM was correlated with the severity of chronic inflammation and acute inflammation. Current knowledge and our results suggest that H. pylori infection and inflammation are the two most important risk factors for IM. The latest European guidelines state that H. pylori eradication does not appear to reverse intestinal metaplasia, but it may slow the progression to neoplasia in patients with intestinal metaplasia (Dinis-Ribeiro et al. 2012). Furthermore, this pathological change gradually and adversely increases with time, accounting for the increased incidence of IM with aging.

In 2005, Liu et al. reported data of 1906 patients infected with H. pylori from nine gastroenterological clinics of seven countries and discovered that the detection rates of IM in the antrum differed from 4 to 55%, which mirrored the respective incidence of gastric cancer in those geographical areas (Liu et al. 2005). Sonnenberg et al. (2010) revealed that the incidence rates of H. pylori infection, chronic active gastritis and IM revealed a similar distribution based on the data of 78,985 unique patients, which included almost all the states of the America. These results indicate that the detection rates of IM have geographical variations. In this study, we analyzed the gastric biopsies of patients hailing from 17 municipal areas of southeastern China. It was found that the detection rates of IM displayed significant differences between regions (from 16.79 to 38.56%), which were consistent with the GDP per capita of every area, but were not associated with H. pylori infection and inflammation. Therefore, we inferred that economic level, represented by the GDP per capita of different regions, may be a potential risk factor for IM. In general, some geographical factors including dietary habits, lifestyle and climate were highly related to digestive diseases and local economic well-being. With economic prosperity, people face fierce competitions and social psychological pressure. Some researchers believe that long-term stress or anxiety can cause autonomic disturbances, which induces the abnormal secretion of gastric acid, leading to mucosal tissue damage (Czekaj et al. 2016). The rapid pace of life constantly leads to unhealthy lifestyles and dietary habits such as irregular meals, fast foods, fast eating, sleep disruption, coffee consumption and less physical activity, which predispose individuals to acid peptic diseases. Due to the limitations of available data, we were unable to evaluate the above factors thoroughly. However, these factors could greatly contribute to the differences in geographical distribution caused by economic disparities in the incidence of IM. At present, GDP per capita, which represents the economic level of the regions, has rarely been studied as an independent factor in correlation with diseases. Hence, the potential effect of GDP per capita on IM needs to be incorporated into future investigations.

Nonetheless, there are still some gaps in the understanding of IM. Due to the limitations of gastroscopic biopsy, lesions may have been omitted, leading to erroneous detection rates. Under these present circumstances, the large-scale application of the latest endoscopic technologies across the country is yet to be accomplished. There are some limitations of this research. First, as a retrospective study, a variety of biases is possible. Fortunately, our sample size was sufficient enough to partly address this limitation. Second, the data we retrieved did not include the symptoms of patients, or personal lifestyle and dietary habits, making us unable to explore the possible relationships between these risk factors and IM. Furthermore, the real H. pylori infection rate in patients with IM should have been higher than the indicated data, but this could be due to the false-negative cases taking proton pump inhibitors or as a result of previous H. pylori eradication therapy. And since H. pylori can only survive in the gastric mucosa, trans-differentiation to intestinal metaplasia could cause natural eradication of this bacterium (Yabuki et al. 1997). Diagnosis of H. pylori infection in this study mainly depended upon RUT, which is the limitation of this study. As most of the patients of IM had possibly received H. pylori eradication therapy in other hospitals, and these records were not available in our database, the real incidence of H. pylori infection might have been underestimated in patients with IM. It is likely to be the reason why we found that the higher the degree of severity of IM, the lower the H. pylori infection rate.

In conclusion, we systematically studied the IM status of southeastern China and verified the risk factors for intestinal metaplasia such as age, male gender, gastric ulcer, bile reflux, H. pylori infection, degree of chronic and acute inflammation, which may lead to the development of more effective tools for IM diagnosis. Moreover, we speculate that gross domestic product per capita of different areas may be a potentially independent risk factor that impacts the difference in geographical distributions of intestinal metaplasia. Additional risk factors should be investigated based on geographical factors such as climate, lifestyle and dietary habits, in an attempt to elucidate the pathogenesis of IM and it is the relationship with GC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81101800), the 12th Six Talents Peak Project of Jiangsu Province (No. 2015-WSN-028), the Research Project of Education Science in the 12th Five Year Plan of Nanjing Medical University (No. NY2222015030) and the Research Project of Chinese Medical Association & Chinese High Education Association (No. 2016B-KC019).

Abbreviations

- IM

Intestinal metaplasia

- GC

Gastric cancer

- AG

Atrophic gastritis

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- EIS

Endoscopy Information System

- OR

Odds ratio

- GU

Gastric ulcer

- DU

Duodenal ulcer

- CI

Chronic inflammation

- AI

Acute inflammation

- L-number

Number of lymphoid follicle

- GDP

Gross domestic product

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Jian-Xia Jiang and Qing Liu have contributed equally to this work.

References

- Chacaltana Mendoza A, Soriano Alvarez C, Frisancho Velarde O (2012) Associated risk factors in patients with gastric intestinal metaplasia with mild gastroduodenal disease. Is it always related to Helicobacter pylori infection? Rev Gastroenterol Peru 32:50–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa P, Haenszel W, Cuello C, Tannenbaum S, Archer M (1975) A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet 2:58–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czekaj R, Majka J, Ptak-Belowska A, Szlachcic A, Targosz A, Magierowska K, Strzalka M, Magierowski M, Brzozowski T (2016) Role of curcumin in protection of gastric mucosa against stress-induced gastric mucosal damage. Involvement of hypoacidity, vasoactive mediators and sensory neuropeptides. J Physiol Pharmacol 67:261–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ (2008) Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology 134:945–952. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Hoed CM, van Eijck BC, Capelle LG, van Dekken H, Biermann K, Siersema PD, Kuipers EJ (2011) The prevalence of premalignant gastric lesions in asymptomatic patients: predicting the future incidence of gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 47:1211–1218. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O’ Connor A, Pereira C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Correia R, Ensari A, Dumonceau JM, Machado JC, Macedo G, Malfertheiner P, Matysiak-Bdnik T, Megraud F, Miki K, O’Morain C, Peek RM, Ponchon T, Ristimaki A, Rembacken B, Carneiro F, Kuipers EJ, European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; European Helicobacter Study Group; European Society of Pathology; Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (2012) Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Endoscopy 44:74–94. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1291491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P (1996) Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 20:1161–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felley C, Bouzourene H, VanMelle MB, Hadengue A, Michetti P, Dorta G, Spahr L, Giostra E, Frossard JL (2012) Age, smoking and overweight contribute to the development of intestinal metaplasia of the cardia. World J Gastroenterol 18:2076–2083. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136(5):E359–E386. doi:10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez JM, Wang AY (2014) Gastric intestinal metaplasia and early gastric cancer in the west: a changing paradigm. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 10(6):369–378 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez CA, Pardo ML, Liso JM, Alonso P, Bonet C, Garcia RM, Sala N, Capella G, Sanz-Anquela JM (2010) Gastric cancer occurrence in preneoplastic lesions: a long-term follow-up in a high-risk area in Spain. Int J Cancer 127:2654–2660. doi:10.1002/ijc.25273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Gu D, Wu X, Reynolds K, Duan X, Yao C, Wang J, Chen CS, Chen J, Wildman RP, Klag MJ, Whelton PK (2005) Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med 353:1124–1134. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa050467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JJ, Lee DH, Lee AR, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N (2015) Characteristics of gastric cancer in peptic ulcer patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 21:4954–4960. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D (2011) Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61:69–90. doi:10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers EJ (1997) Helicobacter pylori and the risk and management of associated diseases: gastritis, ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 11(Suppl 1):71–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung WK, Kim JJ, Kim JG, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR (2000) Microsatellite instability in gastric intestinal metaplasia in patients with and without gastric cancer. Am J Pathol 156:537–543. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64758-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XB, Lu H, Chen HM, Chen XY, Ge ZZ (2008) Role of bile reflux and Helicobacter pylori infection on inflammation of gastric remnant after distal gastrectomy. J Dig Dis 9:208–212. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ponsioen CI, Xiao SD, Tytgat GN, Ten Kate FJ (2005) Geographic pathology of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Helicobacter 10:107–113. doi:10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wu J, Lin XC, Wei N, Lin W, Chang H, Du XM (2014) Evaluating the diagnoses of gastric antral lesions using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging in a Chinese population. Dig Dis Sci 59:1513–1519. doi:10.1007/s10620-014-3027-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuhisa T, Tsukui T (2012) Relation between reflux of bile acids into the stomach and gastric mucosal atrophy, intestinal metaplasia in biopsy specimens. J Clin Biochem Nutr 50:217–221. doi:10.3164/jcbn.11-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milosavljevic T, Kostic-Milosavljevic M, Krstic M, Sokic-Milutinovic A (2014) Epidemiological trends in stomach-related diseases. Dig Dis 32:213–216. doi:10.1159/000357852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YH, Kim N (2015) Review of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia as a premalignant lesion of gastric cancer. J Cancer Prev 20:25–40. doi:10.15430/JCP.2015.20.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleteiro B, Lunet N, Figueiredo C, Carneiro F, David L, Barros H (2007) Smoking, Helicobacter pylori virulence, and type of intestinal metaplasia in Portuguese males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16:322–326. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakitani K, Hirata Y, Watabe H, Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Maeda S, Omata M, Koike K (2011) Gastric cancer risk according to the distribution of intestinal metaplasia and neutrophil infiltration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 26:1570–1575. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06767.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Coorper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Flejou JF, Geboes K, Hattori T, Hirota T, Itabashi M, Iwafuchi M, Iwasshita A, Kim YI, Kirchner T, Klimpfinger M, Koike M, Lauwers GY, Lewin KJ, Oberhuber G, Offiner F, Price AB, Rubio CA, Shimizu M, Shimoda T, Sipponen P, Solcia E, Stolte M, Watanabe H, Yambe H (2000) The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 47:251–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng LM, You GC, Wei WL (2000) Epidemiologic analysis of gastric carcinoma incidence of Yangzhong City from 1991 to 1998. China Oncol 10(2). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3639.2000.02.029.

- Shichijo S, Hirata Y, Niikura R, Hayakawa Y, Yamada A, Ushiku T, Fukayama M, Koike K (2016) Histologic intestinal metaplasia and endoscopic atrophy are predictors of gastric cancer development after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Gastrointest Endosc 84:618–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg A, Lash RH, Genta RM (2010) A national study of Helicobactor pylori infection in gastric biopsy specimens. Gastroenterology 139:1894–1901 e1892; quiz e1812. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Stolte M, Meining A (2001) The updated Sydney system: classification and grading of gastritis as the basis of diagnosis and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol 15:591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong BC, Wong WM, Wang WH (2001) An evaluation of invasive and non-invasive tests for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 15:505–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuki N, Sasano H, Tobita M, Imatani A, Hoshi T, Kato K, Ohara S, Asaki S, Toyota T, Nagura H (1997) Analysis of cell damage and proliferation in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa from patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Pathol 151(3):821–829 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q, Huang MF, Shi XY, Xia B (2009) The clinical and endoscopic analysis of 4957 cases of peptic ulcer diseases. Chin J Clin Gastroenterol 21:275–277 [Google Scholar]