Abstract

Patellofemoral disorders, commonly encountered in sports and orthopedic rehabilitation settings, may result from dysfunction in patellofemoral joint compression. Osseous and soft tissue factors, as well as the mechanical interaction of the two, contribute to increased patellofemoral compression and pain. Treatment of patellofemoral compressive issues is based on identification of contributory impairments. Use of reliable tests and measures is essential in detecting impairments in hip flexor, quadriceps, iliotibial band, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius flexibility, as well as in joint mobility, myofascial restrictions, and proximal muscle weakness. Once relevant impairments are identified, a combination of manual techniques, instrument-assisted methods, and therapeutic exercises are used to address the impairments and promote functional improvements. The purpose of this clinical commentary is to describe the clinical presentation, contributory considerations, and interventions to address patellofemoral joint compressive issues.

Keywords: Flexibility, knee, patellofemoral pain, patellofemoral compression

INTRODUCTION

Patellofemoral disorders comprise nearly 25% of all knee injuries evaluated in orthopedic clinics.1-3 Patellofemoral disorders encompass a large spectrum of pathologies, including chondral injuries, arthritis, instability, and patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS).4 Patellofemoral pain syndrome may be a result of an insidious compressive dysfunction or, less commonly, direct trauma. Annual incidence of PFPS in males is 3.8% and 6.5% in females.2 This pathology is often associated with a poor prognosis and multiple treatment plans have been proposed.5-9 Successful treatment of patellofemoral compressive dysfunction requires a strong understanding of the osseous and soft tissue anatomy of this joint. Abnormalities of these osseous or soft tissue structures may predispose patients to biomechanical abnormalities. In most instances, these compressive disorders maybe addressed with a comprehensive treatment plan addressing soft tissue flexibility and mobility, lower extremity strength, and biomechanical impairments.

Elevated patellofemoral joint compressive force can result in patellofemoral pain from numerous soft tissue structures: synovial plicae, infrapatellar fat pad, rentinaculae, joint capsule, and patellofemoral ligaments.10 Patellofemoral compressive forces can also elevate subchondral bone stress in the patellofemoral joint. It is also believed that, because of high concentration of pain receptors in the subchondral bone, increased stress from high patellofemoral force may also result in pain.10-12 This compressive force, if prolonged, can result in articular cartilage degeneration and decrease in the ability of the cartilage to appropriately distribute patellofemoral joint contact forces.11 As a rehabilitation specialist, it is important to understand the stress levels in the patellofemoral joint during activities of daily living and rehabilitation exercises when treating patients with patellofemoral compressive dysfunction. The purpose of this clinical commentary is to describe the clinical presentation, contributory considerations, and interventions to address patellofemoral joint compressive issues.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patellofemoral compressive pain typically affects younger adults but can also be problematic for adolescents and adults. Typically, in adolescents, this pain is evident during periods of rapid growth.13 In adults, degenerative changes in the patellofemoral joint may also be present, adding to the complexity of the compressive disorder. Patients typically describe a gradual onset of anterior knee pain. This pain is usually associated with the knee being in conditions that lead to increased patellofemoral compression: knee flexion and quadriceps loading. Such activities include squatting, stair climbing, hiking, running and prolonged sitting. Symptoms are rarely present when the patellofemoral joint is not being loaded and compressed (e.g. sleeping, standing, resting).14

Patellofemoral pain is a clinical diagnosis, based on the presence of anterior knee pain while compressive forces are elevated during activities that load the patellofemoral joint. Physical examination usually reveals normal knee range of motion without effusion, and patellar mobility may or may not be normal. While there are a multitude of special tests to help develop a diagnosis, no single clinical test definitively confirms the diagnosis of patellofemoral compression pain. Although there is no single definitive test, pain during squatting is highly prevalent in patients with patellofemoral pain.14,15 It is also important to note that patellofemoral pain is evident in 71-75% of patients with tenderness on palpation of the edges of the patella.15 Palpation of the medial and lateral facets of the patella should be included in the clinical exam of patients suspected of having patellofemoral pain. Patellar grinding/crepitus and apprehension tests have low sensitivity and limited diagnostic accuracy.15 These tests should be used with caution when determining a working diagnosis.

The core criterion required to define a compressive dysfunction of the patellofemoral joint is pain around or behind the patella, which is aggravated by at least one activity that loads the patellofemoral joint during weight bearing on a flexed knee: squatting, stair ambulation, jogging/running, and hopping/jumping.14 Additional criteria that are non-essential, but may be helpful in establishing a diagnosis include crepitus emanating from the patellofemoral joint during knee flexion movements, tenderness on patellar facet palpation, small peri-patellar effusion, and pain while sitting or rising from sitting.16

OSSEOUS CONSIDERATIONS OF THE KNEE

The patella is convex on its anterior surface, but is divided by a longitudinal median ridge on the articular side.17 It resides within the trochlear groove and links the extensor mechanism through connections to the quadriceps tendon at the superior pole and the patellar tendon at its inferior pole.4 The patella has seven total facets but is primarily divided into two large facets located medially and laterally. These medial and lateral facets are important considerations regarding the compressive dysfunction mechanism and time should be taken to palpate the facets during examination. (Figure 1) The lateral facet is longer and more sloped to match the lateral femoral condyle, while the medial facet is smaller, with a shorter and steeper slope.17 The patellar cartilage has greater congruency in the axial plane as compared to in the sagittal plane, contributing to the gliding capability of the joint itself.4,18 This is important to consider during clinical evaluation of the patella mobility.

Figure 1.

Palpation of the medial facet joint of the patella. The patella should be medially glided to allow for proper palpation of the underside medial facet.

The stability of the patella is also dependent on the characteristics of the trochlear grove. The trochlear groove depth is approximately 5.2mm, with the lateral femoral condyle being 3.4mm higher than the medial femoral condyle in the axial plane.17 The trochlear groove deepens as it extends distally and deviates laterally before it terminates at the femoral notch. The facets transition into the medial and lateral femoral condyles. Trochlear dysplasia is characterized by a loss of the normal concave anatomy and depth of the trochlear groove.19 This loss of normal anatomy creates a flat trochlea with highly asymmetric facets. This asymmetry predisposes to patellar dislocation during knee flexion secondary to loss of bony restraints within the groove.4

SOFT TISSUE CONSIDERATIONS OF THE KNEE

The quadriceps patella mechanism, made up of the quadriceps and patella tendon, is the primary stabilizer of the patella with insertions on both the superior and inferior poles of the patella. The superior portion is created by the quadriceps tendon, which is a convergence of the rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus lateralis, and vastus intermedius. The inferior portion is created by the patellar tendon, which attaches at the tibial tubercle. Separating the posterior part of the tendon from the synovial membrane of the joint is the infrapatellar fat pad, whereas a bursa separates the tendon from the tibia more distally.4 The infrapatellar fat pad is an intracapsular and extrasynovial tissue that is highly innervated and a potential source of anterior knee pain.16

Medial soft tissues of the patellofemoral joint include the vastus medialis obliquus, medial patellofemoral ligament, the medial patellotibial ligament and the medial retinaculum. The medial patellofemoral ligament is the primary passive restraint to lateral patellar translation. The medial patellofemoral ligament is vital to patellar stability and laxity in this structure may result in altered compressive forces in the patellofemoral joint. Assessment of these medial structures may be performed by a patella mobility test as well as medial border and medial facet palpation. Pain elicited may be indicative of elevated compressive forces on the medial side of the patella.

The lateral soft tissue restraints are composed of the superficial and deep layers of the retinaculum. The superficial layers are comprised of the oblique lateral retinaculum and the deep layer is comprised of the oblique and transverse fibers of the lateral retinaculum.4 These fibers are referred to as the patellotibial and the epicondylopatellar bands.20 Tightness of these lateral structures may cause a pull on the patella in the lateral direction causing a lateral tilt of the patella. A lateral tilt may increase compressive forces to the lateral facet on the patella and cause progressive degenerative changes over time. Assessment for lateral tightness should be a component of an evaluation for patellofemoral pain. This assessment should include palpation of the lateral border and lateral patellar facet. It should also include assessment of iliotibial band (ITB) tightness. The ITB is intricately involved with the lateral soft tissue structures of the patellofemoral joint and plays a supportive role in the lateral stability. Specifics of ITB assessment will be covered later in this clinical commentary.

MECHANICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Patellofemoral motion requires a complex interaction between the bony and soft tissue structures. Since the patella is a sesamoid bone, abnormalities of the bony congruency, femoral control and the soft tissue structures can cause malalignment and contribute to patellar tracking issues.4 This maltracking may cause an increase in compressive forces during knee flexion. From 0 ° to 30 ° of knee flexion, the primary restraints to lateral patellofemoral translation are soft tissue structures, including the medial patellofemoral ligament, vastus medialis obliquus and the medial retinaculum. From 0 to 30 °, the medial patellofemoral ligament becomes the primary restraint to lateral translation, while the primary soft tissue restraints on the lateral side, including the superficial and deep layers of the lateral retinaculum, increase compressive forces and stability.4 During initiation of knee flexion, a medial patellar shift occurs allowing the patella to engage in the trochlear groove.4 As the knee continues to flex from 20 ° to 30 ° of knee flexion, patellar stability increases due to bony contributions and soft tissue structures, as the patella engages in the trochlea.21 Progressing flexion to 60 °, contact pressure increases and moves from distal to proximal.22

Once the knee flexes to 90 ° there is increasing posteriorly directed force exerted from the patellar and quadriceps tendon, which increase the overall joint reactive force and create a high level of compressive force.4 Escamilla et al showed that, between 80 ° and 90 ° of knee flexion, the short wall squat (feet closer to the wall) produced the greatest patellofemoral compressive force as compared to a long wall squat (feet away from wall).12 Rosenberg et al. and Andriacchi et al showed that the highest patellofemoral load during stair climbing is seen at 60 ° of knee flexion.23,24 Based on these studies, it can be assumes that these positions and activities between 60 ° and 90 ° degrees of knee flexion manifest the greatest compressive forces in the patellofemoral joint and should be considered during assessment and treatment.

TREATMENT OF PATELLOFEMORAL COMPRESSION

Treatment of patellofemoral compressive issues starts with identification of relevant impairments through a physical therapy examination. Impairments in muscle-tendon flexibility, joint mobility, and myofascial restrictions can be reliably examined using established tests and measures. Proximal and distal joint factors also influence patellofemoral stress and this topic of regional interdependence is briefly summarized in this commentary and covered in depth by other authors throughout this journal issue. Once relevant impairments are found, a combination of manual techniques, instrument-assisted methods, and therapeutic exercises are used to address the impairments and promote functional improvements. Select impairments and strategies to address these impairments will be discussed in the following sections.

Hip Flexor and Quadriceps Flexibility

Impaired hip flexor and quadriceps flexibility has been documented in patients with PFPS.6,25-27 In a case-control study, Piva et al. showed that patients diagnosed with PFPS had significantly less quadriceps length when compared to healthy subjects.27 Decreased quadriceps flexibility results in increased patellofemoral compression, as the tight quadriceps muscle and tendon compresses the patella into the trochlea via its posterior direction of pull.28 Further, hip flexor tightness is associated with an anterior pelvic tilt posture, which may result in femoral internal rotation, patellar maltracking, decreased patellofemoral contact area, and therefore, increased patellofemoral stress.29,30

Two special tests are particularly useful in testing hip flexor and quadriceps flexibility. The modified Thomas test, performed with the patient in the supine position at the edge of an exam table, determines hip flexor flexibility by measuring hip flexion/extension angle relevant to the horizontal line parallel to the table surface.31 It is important for the physical therapist to passively and maximally flex the non-tested hip to ensure that the pelvis is set in a posteriorly tilted position. The tested leg should be lowered only after this standard pelvic position is established, and this position should be maintained throughout the test procedure. The posteriorly tilted pelvic position helps to standardize lumbar spine position into that of minimal lordosis, thereby eliminating the influence of spine position on apparent flexibility of psoas major, which is attached to all lumbar spinal segments.32 The modified Thomas test can be quantified using a standard goniometer or an inclinometer, with high intra- and inter-rater reliability (Figure 2).33 In addition to assessing hip flexion angle, knee extension angle is assessed in the same position as in the Thomas test as a measure of rectus femoris flexibility.34

Figure 2.

Modified Thomas Test: evaluation of the hip flexion angle using a goniometer or digital level. The rectus femoris mobility may also be objective with a knee angle measurement.

Ely's test, performed with the patient in prone position, determines rectus femoris flexibility by the clinician passively flexing the knee and looking for the anterior surface of the hip to lift up from the table surface, indicating increased anterior pelvic tilt. This test can be quantified using a goniometer or inclinometer to measure knee flexion angle or tibial angle relevant to the table surface, with moderate to good reliability.35,36

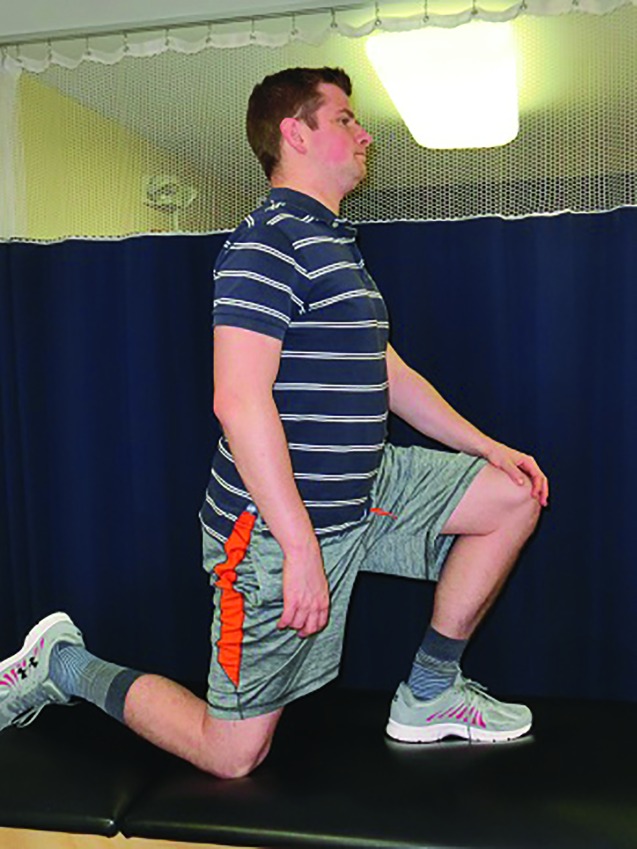

Many stretching techniques are available for addressing hip flexor and quadriceps flexibility. Choosing which techniques to be prescribed to a patient depends on the patient's positional preference, patient's tolerance to stretch, and effectiveness of the stretch. The authors routinely use the Thomas test position with the involved leg stabilized as an intervention technique (Figure 3). The patient must be instructed to hold the contralateral thigh in maximum hip flexion in order to ensure the posteriorly tilted pelvic position. Another effective stretching technique is the half-kneeling hip flexor stretch (Figure 4). For this stretch, it is important that the patient keeps his/her trunk in the upright position and maintains a moderate abdominal muscle contraction to prevent excessive lumbar lordosis. Prone quadriceps stretching can also be effective for addressing rectus femoris flexibility. A rolled-up towel can be inserted under the distal thigh to enhance the stretch. Each passive stretching intervention should be held for a minimum total of four minutes, which can be broken into shorter repetitions, to promote carryover in flexibility gains.37

Figure 3.

Stretching Thomas Test: The Thomas Test maybe transitioned into a manual hip flexor stretch; a rectus femoris stretch maybe included with using leg to increased involved lower extremity flexion angle.

Figure 4.

Half Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch: Pt high kneels on knee of the lower extremity with the tight hip flexor, with contralateral foot flat on the ground. Pt gentle leans forward until a stretch in felt in the involved LE.

Several authors have shown that addressing hip flexor flexibility is associated with symptomatic improvement and functional recovery in patients with PFPS.6,38,39 Peeler et al, in a prospective cohort study, showed that a three-week home stretching program targeting the quadriceps was effective at significantly improving functional outcomes scores in patients with PFPS.38

Tensor Fascia Latae and Iliotibial Band (ITB) Flexibility

Flexibility of the tensor fascia latae and ITB has been implicated in PFPS.6,40,41 In a case-control study, Hudson et al found that patients with PFPS had significantly less hip adduction during Ober's test compared to healthy subjects.40 Tightness in the tensor fascia latae and its dense fascial extension, the ITB, is theorized to cause lateral patellar displacement, decreased patellofemoral contact area, and therefore, increased patellofemoral stress.42-44 In addition, tight ITB and lateral patellar retinaculum may lead to ITB friction syndrome, although the etiology of this pathology has been contested.45-47

The ITB is continuous on its proximal end with tensor fascia latae anteriorly and gluteus maximus posteriorly. Tests of ITB flexibility must encompass both the anterior and posterior aspects of this complex structure. Ober's test, performed in the side-lying position, tests for tensor fascia latae and ITB flexibility by measuring the hip adduction angle due to gravity.48 It is important that the patient flexes the non-tested hip and stabilizes this leg in this position by hooking the hand around the leg and holding onto the edge of the table (Figure 5). This ensures that the pelvic position is standardized in the posteriorly tilted position. In this position, the tested (top) leg is held in the examiner's arm and the patient's hip is passively abducted, extended, then allowed to adduct due to the force of gravity. Because passive hip extension past neutral is required to clear the ITB over the greater trochanter, Ober's test is valid only if the Thomas test is negative to allow this amount of hip extension. Performing Ober's test without standardizing the pelvic position or in the presence of hip flexor tightness results in a false negative test. Ober's test can be quantified by placing an inclinometer at the distal thigh, and this methodology has been found to have excellent reliability.35 Validity of Ober's test as a measure of ITB and tensor fascia latae flexibility has been questioned, based on serial anatomic transections.49

Figure 5.

Ober Test is performed in the sidelying position. To properly lock in the pelvic stability, have the patient grab the table under his lower leg, putting his hip and knee in a flexed position.

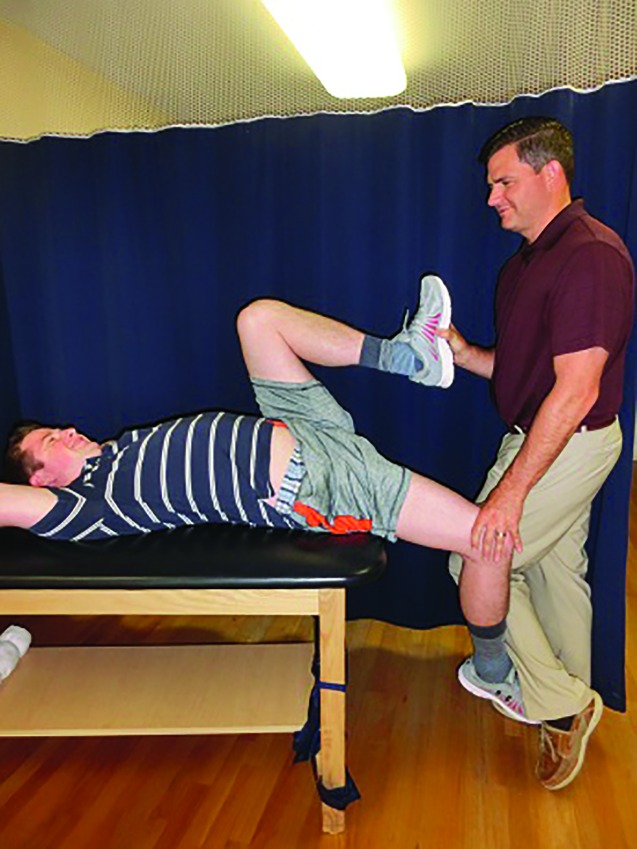

While Ober's test was designed to assess the anterior component of ITB flexibility, the posterior component can be assessed by the supine crossover test. The supine crossover test does not have established validity or reliability, however, it is routinely used as a qualitative measure of the posterior component of ITB flexibility. The test is performed with the patient in the supine position, and the examiner passively flexes the tested hip about 70 degrees and adducts until resistance is felt from the ITB (Figure 6). Care must be taken to avoid lateral tilt of the pelvis during this test. The pelvis should be stabilized manually by the therapist or monitored for movement. Bilateral comparison may reveal a unilateral tightness of the posterior component of the ITB.

Figure 6.

Supine ITB Assessment: The ITB may also be assessed by placing the patient in the supine position and adducting the lower extremity. This angle maybe documented for an objective measurement.

Improving ITB flexibility can be a challenge. Depending on what structures are tight (i.e., posterior versus anterior component) and the patient's preferences, one or more of the following stretches can be prescribed. The Ober's test position can be used to perform a therapist-assisted stretch. The supine crossover test position can be used as a therapist-assisted stretch or self-stretch by using a strap or propping the leg up against an immovable object (e.g., wall or chair). The stretch can also be performed in the standing position by crossing the legs and laterally leaning the trunk. Adding the trunk and arm movement can enhance the stretching effect and promote stretching of the entire lateral myofascial line.50,51Addressing ITB flexibility is associated with relief in patellofemoral pain.6,52 Tyler et al., in a prospective cohort study; found that normalizing Ober's test was one of the significant predictors of treatment success after six weeks of physical therapy for patients with PFPS.6

Hamstrings and Gastrocnemius Flexibility

Other types of soft tissue flexibility that influence patellofemoral compression and pain include limitations of the hamstrings and gastrocnemius. Hamstring tightness theoretically causes posterior glide of the proximal tibia on the femur, therefore, an alteration in the quadriceps vector, which results in increased compression of the patella on the femur. This association has been supported in cross-sectional studies of patients with patellofemoral pain.25,27,53 Whyte et al. showed in a biomechanical study that individuals with hamstring tightness had increased patellofemoral stress and reaction force during a squat task, compared to individuals without hamstring tightness.53 Gastrocnemius tightness may have a similar influence on patellofemoral biomechanics as the hamstrings, however, this mechanism has not been empirically demonstrated. Witvrow et al. identified in a prospective study that gastrocnenimus inflexibility at baseline resulted in increased risk of developing patellofemoral pain during a one-year period in college athletes.26 Additionally, it should be noted that gastrocnemius tightness may be compensated for during gait by increased motion at the midtarsal joints, leading to increased subtalar joint motion, tibial and femoral rotation, and patellofemoral compression.54

Flexibility of the hamstrings and gastrocnemius can be readily assessed with several examination techniques. To assess hamstring flexibility, the straight leg raise and 90/90 knee extension tests have been previously used by different groups and have established reliability.27,35,39 Gastrocnemius flexibility can be assessed with the patient in supine or prone position using the Silfverskiöld test.55 This test involves taking the difference in ankle dorsiflexion range of motion between the knee slightly flexed and the knee fully extended. A difference of 10 degrees or larger suggests a gastrocnemius contracture.56 Gastrocnemius flexibility may also be assessed in a standing, weight-bearing position.26

Intervention for hamstring and gastrocnemius flexibility follows the same stretching guidelines as in the previous sections. Hamstrings can be stretched in the straight leg raise position by the patient using a strap or with therapist assistance. Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques (e.g., hold-relax or contract-relax) may enhance the stretch by improving the patient's tolerance to stretch.57,58 Gastrocnemius is optimally stretched in the standing position, with the involved foot behind the uninvolved foot, and the knee extended on the uninvolved side. Care must be taken to avoid abducting the involved foot, which causes excessive motion at the midtarsal joints. Shoes or additional arch support may be used to ensure that the stretch is applied to the gastrocnemius instead of at the midtarsal joints.

Joint Mobility

Patellofemoral joint mobility is tested by qualitative assessment of joint accessory motions. Patellar glide in superior, inferior, medial, and lateral directions can be assessed with the patient's knee in full extension in order to disarticulate the patella from the femoral condyles and allow for passive glides. The physical therapist manually moves the patella in each direction and assesses the excursion of movement, as well as the quality of the end-feel. Limited patellar medial glide has been implicated in the etiology of patellofemoral pain.41 Patellar tilt, in medial or lateral directions, may be assessed by respectively pressing the lateral or medial border of the patella and assessing the excursion of patellar rotation in the transverse plane. Patellar rotation in the frontal plane may be assessed by manually holding the patella with two hands and rotating the patella in each direction. Simultaneous patellar mobility restrictions in two or more planes is common, especially the combination of decreased medial tilt and medial glide. It is important to examine patellar mobility in all directions and document pertinent findings (i.e., hypo-mobile, within normal limits, or hyper-mobile), as subsequent treatment should target only the directions that are restricted.

Patellar mobilization is the mainstay of treatment for patellar hypo-mobility. Patellar mobilizations are typically performed manually by a physical therapist; however, some of the techniques may be instructed to the patient to be performed at home. Self-mobilization may be an effective method because of increased dosage of treatment and improved patient self-efficacy. The patella is manually held and moved in the direction of restriction, using oscillatory motions or static holds. By combining patellar mobilization with therapist-assisted static stretching is effective, particularly for the iliotibial band (ITB) and lateral patellar retinaculum.

Patellar mobilization is commonly used in the treatment of patellofemoral pain, however, empirical evidence showing its effectiveness is limited. This may be due to the lack of a valid and reliable clinical examination technique for patellar position or mobility without the use of specialized instrumentation.59,60 Presence of joint mobility impairment in patients with patellofemoral pain has been questioned, with one cross-sectional study showing no difference in patellar mobility between adults with and without patellofemoral pain.59 It is possible that subsets of patients with patellofemoral pain exist with different impairment patterns, and not all patients with the same pathology present with impaired joint mobility.61

Myofascial Considerations

Myofascial restrictions may contribute to patellofemoral compression and pain. Fascia lata, the deep fascia of the thigh, is extensive and structurally strong, and continuous deeply with the lateral intermuscular septum and superficially and laterally with the ITB.62 Myofascial tightness in the thigh may lead to over-constraining of the patella and increased compression in the patellofemoral joint and under the lateral retinaculum.63 Additionally, active myofascial trigger points in the thigh may directly refer pain into and around the knee.64

Myofascial restrictions may be assessed by direct palpation of the soft tissues and trigger points. An active trigger point is characterized as a tender nodule in a taut band within a muscle, where manual compression triggers a local muscle twitch response or referred pain to an area other than where the compression is applied.65 Identification of an active trigger point following the criteria above has moderate inter-rater reliability.66,67

Once myofascial restrictions are found, several intervention strategies are available. Active trigger points may be treated by direct manual compression, passive stretch of the involved muscle, and neuromuscular re-education by performing therapeutic exercises which target that involved muscle. This combination of interventions in physical therapy may be as effective as dry needling in relieving myofascial pain.68

Foam roller and stick roller are popular tools used in physical therapy to address myofascial restrictions, improve flexibility, and increase joint range of motion. Several groups of researchers have reported that applying a foam roller or stick roller on the thigh resulted in an increase in quadriceps, hamstrings, or hip flexor flexibility and knee or hip joint range of motion in healthy subjects.69-74 However, it is unknown if these effects were sustained in the long term or the results are generalizable to a clinical patient population. Instrument-assisted soft-tissue mobilization may also be beneficial in addressing myofascial restrictions. In one randomized trial, an instrument-assisted technique was superior to foam rolling in increasing knee flexion range of motion and hamstring flexibility after one intervention session in healthy subjects.75 Further scientific inquiry is warranted to establish the clinical utility and the mechanisms of action of these various myofascial intervention techniques.

Strengthening Component to Compressive Issues

Soft tissue mobility is one of the primary clinical considerations when assessing patella compressive dysfunction, however, as early as 1976, Nicholas et al recognized that patients with patellofemoral dysfunction presented with the greatest amount of muscle weaknesses of all the injured groups tested. These weaknesses included hip flexors, hamstring and quadriceps.76 Nicholas et al noted the linkage weakness from the hip to the ankle in these patients.76 Overall lower extremity assessment and strengthening is a key component to proper treatment of patellofemoral conditions.

Multiple authors have highlighted the importance of proximal hip strengthening for patients with patellofemoral dysfunction. Fukuda et al. showed that adding hip strengthening to a conventional knee rehab program in patients with PFPS produced better results in pain, lower extremity scores, and functional tests compared to those simply using a knee rehab program.8 Dolak et al showed faster improvement in anterior knee pain with the addition of a hip strengthening program, compared to a standard knee rehab program.7 Khayambashi et al. showed that simply prescribing hip external rotation and hip abduction strengthening exercises to patients with PFPS resulted in normalized pain, improved function, and significant gains in hip strength after eight weeks.77

Work by Tyler et al showed not only was it important to normalize hip flexibility, but normalizing hip flexion strength was a key component to a successful outcome in patients with patellofemoral pain.6 By resolving three key factors, namely normalizing Ober's test side to side, normalizing the Thomas test side to side, and improving hip flexion strength by more than 20% (measured with a hand held dynamometer), a successful outcome was reached in 93% of patients. If only two of these factors were resolved, a success rate of 75% was reached. If only one of these goals was reached, there was only a 27% success rate. Each of these factors plays a large part in successful outcomes in these patients, by identifying these factors and normalizing them, a high success rate is attainable.

CONCLUSION

Each patient with patellofemoral compressive issue presents with a unique set of impairments. Key impairments associated with patellofemoral compressive issues can be reliably assessed using the established tests and measures described in this paper. Once these key impairments are identified, a wide range of intervention techniques, including therapeutic exercises, manual therapy, and instrument-assisted methods, can be implemented to address the impairments and promote functional recovery. Once a decrease in compression and improvement in soft tissue mobility have been achieved, strengthening of the hip and lower extremity muscles is a key component that should be considered. Selection of specific intervention techniques must take into account patient's preferences, skills and tools available to the therapist, and available evidence as summarized in this clinical commentary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kannus P Aho H Jarvinen M Niittymaki S. Computerized recording of visits to an outpatient sports clinic. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(1):79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blond L Hansen L. Patellofemoral pain syndrome in athletes: a 5.7-year retrospective follow-up study of 250 athletes. Acta Orthop Belg. 1998;64(4):393-400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baquie P Brukner P. Injuries presenting to an Australian sports medicine centre: a 12-month study. Clin J Sport Med. 1997;7(1):28-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman SL Plackis AC Nuelle CW. Patellofemoral anatomy and biomechanics. Clin Sports Med. 2014;33(3):389-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boling M Padua D Marshall S Guskiewicz K Pyne S Beutler A. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(5):725-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyler TF Nicholas SJ Mullaney MJ McHugh MP. The role of hip muscle function in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(4):630-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolak KL Silkman C Medina McKeon J Hosey RG Lattermann C Uhl TL. Hip strengthening prior to functional exercises reduces pain sooner than quadriceps strengthening in females with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41(8):560-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda TY Melo WP Zaffalon BM, et al. Hip posterolateral musculature strengthening in sedentary women with patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled clinical trial with 1-year follow-up. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(10):823-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lan TY Lin WP Jiang CC Chiang H. Immediate effect and predictors of effectiveness of taping for patellofemoral pain syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1626-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biedert RM Sanchis-Alfonso V. Sources of anterior knee pain. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21(3):335-347, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Besier TF Draper CE Gold GE Beaupre GS Delp SL. Patellofemoral joint contact area increases with knee flexion and weight-bearing. J Orthop Res. 2005;23(2):345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escamilla RF Zheng N Macleod TD, et al. Patellofemoral joint force and stress during the wall squat and one-leg squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(4):879-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witvrouw E Callaghan MJ Stefanik JJ, et al. Patellofemoral pain: consensus statement from the 3rd International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat held in Vancouver, September 2013. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(6):411-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crossley KM Callaghan MJ van Linschoten R. Patellofemoral pain. BMJ. 2015;351:h3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nunes GS Stapait EL Kirsten MH de Noronha M Santos GM. Clinical test for diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2013;14(1):54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crossley KM Stefanik JJ Selfe J, et al. 2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 1: Terminology, definitions, clinical examination, natural history, patellofemoral osteoarthritis and patient-reported outcome measures. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(14):839-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh W. Recurrent dislocation of the knee in the adult. In: DeLee J, Drez D, Miller MD, eds. DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine : Principles and Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 2003:1710–1749. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed AM Burke DL Hyder A. Force analysis of the patellar mechanism. J Orthop Res. 1987;5(1):69-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merchant AC Mercer RL Jacobsen RH Cool CR. Roentgenographic analysis of patellofemoral congruence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(7):1391-1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dejour D Saggin P. Disorders of the patellofemoral joint. In: Scott WN Insall JN, eds. Insall & Scott Surgery of the Knee. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schepsis AA. Patellar instability [video]. In: Grana WA, ed. Orthopaedic Knowledge Online: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.White BJ Sherman OH. Patellofemoral instability. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2009;67(1):22-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg AG Andriacchi TP Barden R Galante JO. Patellar component failure in cementless total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988(236):106-114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andriacchi TP Natarajan RN Hurwitz DE. Musculoskeletal dynamics, locomotion, and clinical applications. In: Mow VC Hayes WC, eds. Basic Orthopedics Biomechanics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincot-Raven; 1997:37-68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AD Stroud L McQueen C. Flexibility and anterior knee pain in adolescent elite figure skaters. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11(1):77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witvrouw E Lysens R Bellemans J Cambier D Vanderstraeten G. Intrinsic risk factors for the development of anterior knee pain in an athletic population. A two-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):480-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piva SR Goodnite EA Childs JD. Strength around the hip and flexibility of soft tissues in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35(12):793-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amis AA. Current concepts on anatomy and biomechanics of patellar stability. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bazett-Jones DM Cobb SC Huddleston WE O'Connor KM Armstrong BS Earl-Boehm JE. Effect of patellofemoral pain on strength and mechanics after an exhaustive run. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(7):1331-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagwell JJ Fukuda TY Powers CM. Sagittal plane pelvis motion influences transverse plane motion of the femur: Kinematic coupling at the hip joint. Gait Posture. 2016;43:120-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey D. Assessment of the flexibility of elite athletes using the modified Thomas test. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32(1):68-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogduk N Pearcy M Hadfield G. Anatomy and biomechanics of psoas major. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1992;7(2):109-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clapis PA Davis SM Davis RO. Reliability of inclinometer and goniometric measurements of hip extension flexibility using the modified Thomas test. Physiother Theory Pract. 2008;24(2):135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peeler JD Anderson JE. Reliability limits of the modified Thomas test for assessing rectus femoris muscle flexibility about the knee joint. J Athl Train. 2008;43(5):470-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piva SR Fitzgerald K Irrgang JJ, et al. Reliability of measures of impairments associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peeler J Anderson JE. Reliability of the Ely's test for assessing rectus femoris muscle flexibility and joint range of motion. J Orthop Res. 2008;26(6):793-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McHugh MP Cosgrave CH. To stretch or not to stretch: the role of stretching in injury prevention and performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(2):169-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peeler J Anderson JE. Effectiveness of static quadriceps stretching in individuals with patellofemoral joint pain. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(4):234-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pourahmadi MR Ebrahimi Takamjani I Hesampour K Shah-Hosseini GR Jamshidi AA Shamsi MB. Effects of static stretching of knee musculature on patellar alignment and knee functional disability in male patients diagnosed with knee extension syndrome: A single-group, pretest-posttest trial. Man Ther. 2016;22:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hudson Z Darthuy E. Iliotibial band tightness and patellofemoral pain syndrome: a case-control study. Man Ther. 2009;14(2):147-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puniello MS. Iliotibial band tightness and medial patellar glide in patients with patellofemoral dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;17(3):144-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mc CJ. The management of chondromalacia patellae: a long term solution. Aust J Physiother. 1986;32(4):215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herrington L Rivett N Munro S. The relationship between patella position and length of the iliotibial band as assessed using Ober's test. Man Ther. 2006;11(3):182-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwak SD Ahmad CS Gardner TR, et al. Hamstrings and iliotibial band forces affect knee kinematics and contact pattern. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(1):101-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noble CA. Iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(4):232-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellis R Hing W Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome--a systematic review. Man Ther. 2007;12(3):200-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fairclough J Hayashi K Toumi H, et al. Is iliotibial band syndrome really a friction syndrome? J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(2):74-76; discussion 77-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ober FR. The roleof the iliotibial band and fascia lata as a factor in the causation of low-back disabilities and sciatica. J Bone Joint Surg. 1936;18(1):105-110. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willett GM Keim SA Shostrom VK Lomneth CS. An Anatomic investigation of the Ober Test. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):696-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilke J Krause F Vogt L Banzer W. What is evidence-based about myofascial chains: A systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):454-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fredericson M White JJ Macmahon JM Andriacchi TP. Quantitative analysis of the relative effectiveness of 3 iliotibial band stretches. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(5):589-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Neill DB Micheli LJ Warner JP. Patellofemoral stress. A prospective analysis of exercise treatment in adolescents and adults. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(2):151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whyte EF Moran K Shortt CP Marshall B. The influence of reduced hamstring length on patellofemoral joint stress during squatting in healthy male adults. Gait Posture. 2010;31(1):47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karas MA Hoy DJ. Compensatory midfoot dorsiflexion in the individual with heelcord tightness: Implications for orthotic device designs. J Prosthetics Orthotics. 2002;14(2):82-93. [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeOrio JK Lewis JS Jr. Silfverskiold's test in total ankle replacement with gastrocnemius recession. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(2):116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DiGiovanni CW Kuo R Tejwani N, et al. Isolated gastrocnemius tightness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-a(6):962-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Hora J Cartwright A Wade CD Hough AD Shum GL. Efficacy of static stretching and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretch on hamstrings length after a single session. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(6):1586-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toft E Espersen GT Kalund S Sinkjaer T Hornemann BC. Passive tension of the ankle before and after stretching. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(4):489-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ota S Nakashima T Morisaka A Ida K Kawamura M. Comparison of patellar mobility in female adults with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(7):396-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong YM Ng GY. The relationships between the geometrical features of the patellofemoral joint and patellar mobility in able-bodied subjects. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(2):134-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.S. Wendell Holmes J William G. Clancy J. Clinical classification of patellofemoral pain and dysfunction. J OrthopSports Phys Ther. 1998;28(5):299-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benjamin M. The fascia of the limbs and back--a review. J Anat. 2009;214(1):1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fairclough J Hayashi K Toumi H, et al. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. J Anat. 2006;208(3):309-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Torres-Chica B Nunez-Samper-Pizarroso C Ortega-Santiago R, et al. Trigger points and pressure pain hypersensitivity in people with postmeniscectomy pain. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(3):265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shah JP Thaker N Heimur J Aredo JV Sikdar S Gerber L. Myofascial trigger points then and now: A historical and scientific perspective. Pm r. 2015;7(7):746-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerwin RD Shannon S Hong CZ Hubbard D Gevirtz R. Interrater reliability in myofascial trigger point examination. Pain. 1997;69(1-2):65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bron C Franssen J Wensing M Oostendorp RA. Interrater reliability of palpation of myofascial trigger points in three shoulder muscles. J Man Manip Ther. 2007;15(4):203-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rayegani SM Bayat M Bahrami MH Raeissadat SA Kargozar E. Comparison of dry needling and physiotherapy in treatment of myofascial pain syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33(6):859-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.MacDonald GZ Penney MD Mullaley ME, et al. An acute bout of self-myofascial release increases range of motion without a subsequent decrease in muscle activation or force. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(3):812-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vigotsky AD Lehman GJ Contreras B Beardsley C Chung B Feser EH. Acute effects of anterior thigh foam rolling on hip angle, knee angle, and rectus femoris length in the modified Thomas test. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Junker DH Stoggl TL. The foam roll as a tool to improve hamstring flexibility. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29(12):3480-3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mohr AR Long BC Goad CL. Effect of foam rolling and static stretching on passive hip-flexion range of motion. J Sport Rehabil. 2014;23(4):296-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bradbury-Squires DJ Noftall JC Sullivan KM Behm DG Power KE Button DC. Roller-massager application to the quadriceps and knee-joint range of motion and neuromuscular efficiency during a lunge. J Athl Train. 2015;50(2):133-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sullivan KM Silvey DB Button DC Behm DG. Roller-massager application to the hamstrings increases sit-and-reach range of motion within five to ten seconds without performance impairments. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013;8(3):228-236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Markovic G. Acute effects of instrument assisted soft tissue mobilization vs. foam rolling on knee and hip range of motion in soccer players. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015;19(4):690-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nicholas JA Strizak AM Veras G. A study of thigh muscle weakness in different pathological states of the lower extremity. Am J Sports Med. 1976;4(6):241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khayambashi K Mohammadkhani Z Ghaznavi K Lyle MA Powers CM. The effects of isolated hip abductor and external rotator muscle strengthening on pain, health status, and hip strength in females with patellofemoral pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(1):22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]