Abstract

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score has reduced accuracy for liver transplantation (LT) wait-list mortality when MELD ≤20. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a biomarker associated with systemic inflammation and may predict cirrhotic decompensation and death. We aimed to evaluate the prognostic utility of high NLR (≥4) for liver-related death among low MELD patients listed for LT, controlling for stage of cirrhosis. In a nested case-control study of cirrhotic adults awaiting LT (February 2002 to May 2011), cases were LT candidates with a liver-related death and MELD ≤20 within 90 days of death. Controls were similar LT candidates who were alive for ≥90 days after LT listing. NLR and other covariates were assessed at the date of lowest MELD, within 90 days of death for cases and within 90 days after listing for controls. There were 41 cases and 66 controls; MELD scores were similar. NLR 25th, 50th, 75th percentile cutoffs were 1.9, 3.1, and 6.8. NLR was ≥4 in 25/41 (61%) cases and in 17/66 (26%) controls. In univariate analysis, NLR (continuous ≥1.9, ≥4, ≥6.8), increasing cirrhosis stage, jaundice, encephalopathy, serum sodium, and albumin and nonselective beta-blocker use were significantly (P < 0.01) associated with liver-related death. In multivariate analysis, NLR of ≥1.9, ≥4, ≥6.8 were each associated with liver-related death. Furthermore, we found that NLR correlated with the frequency of circulating low-density granulocytes, previously identified as displaying proinflammatory properties, as well as monocytes. In conclusion, elevated NLR is associated with liver-related death, independent of MELD and cirrhosis stage. High NLR may aid in determining risk for cirrhotic decompensation, need for increased monitoring, and urgency for expedited LT in candidates with low MELD.

Since 2002, the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scoring system—now a robust, validated predictor of short-term survival in independent groups of patients with a wide spectrum of liver disease(1)—has formed the foundation of the deceased liver allocation system in the United States. However, although MELD has successfully reduced liver transplantation (LT) wait-list registrations and waiting-list mortality,(2–4) MELD’s accuracy in predicting mortality is reduced in patients with cirrhosis with MELD ≤20.(5,6)

This “low MELD” cohort of patients comprises a significant proportion of candidates listed for LT.(7) On the basis of the current body of literature describing this population, we know that there are risk factors (including clinical sequelae of portal hypertension such as ascites), as well as objective markers (such as hyponatremia), that predict mortality independent of MELD itself.(8–13) Further refining our ability to predict mortality, by using easily accessible and objective laboratory parameters similar to those used to create the MELD score itself, would have important consequences in the LT community’s ability to improve outcomes in low MELD candidates.

The peripheral neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is one such parameter. A high NLR reflects systemic inflammation, a complex pathophysiologic process that underlies the progression to advanced cirrhosis.(14,15) Furthermore, NLR is an emerging biomarker, shown to predict outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease(16) as well as solid tumor malignancy.(17) A meta-analysis of 100 studies comprising 40,559 patients with solid tumor malignancies demonstrated that, for all disease subgroups, sites, and stages, NLR >4 was associated with a statistically significant hazard ratio for overall survival.(18) Recently, NLR has also emerged as a predictor of mortality independent of MELD scores in patients with cirrhosis and with hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as in candidates on the LT waiting list.(19–22)

In this study, we aimed to specifically evaluate the prognostic utility of high NLR (≥4) for liver-related death among low MELD patients listed for LT. We also sought to control for cirrhosis stage; the D’Amico Stages of Cirrhosis model (Table 1) is a cumulative clinical staging tool that helps identify low MELD patients at higher risk for liver-related death.(6,23,35)

TABLE 1.

Prognostic Cirrhosis Stage

| Stage | Definition 2010* | Definition 2014† | 5-year Mortality Rate, %† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compensated cirrhosis without varices or ascites | Compensated cirrhosis without varices | 1.5 |

| 2 | Compensated cirrhosis with varices but without variceal bleeding or ascites | Compensated cirrhosis with varices | 10 |

| 3 | Variceal bleeding but have never had ascites | Bleeding without other disease complications | 20 |

| 4 | Ascites with or without varices, but no history of variceal bleeding | First nonbleeding decompensating event | 30 |

| 5 | Ascites and variceal bleeding | Any second decompensating event | 88 |

Patients and Methods

PATIENT POPULATION

In this nested case-control design study at the University of Colorado Hospital (UCH), we performed 1:n matching for cases and controls. Details of subject recruitment for this study were reported in a previous description of the study cohort(6) and are included here for completeness. Cases with low MELD (≤20) scores and liver-related deaths were identified by querying the UCH LT database for patients who died after they had been listed for LT but who had not yet undergone LT during the period of February 2002 to May 2011. We included all adults who were 18–75 years old; had clinical, histological, or radiographic evidence of cirrhosis; were listed for primary LT; and had a laboratory MELD score ≤20 within 90 days of death. The study protocol had a prior approval from the institutional review board of the University of Colorado.

Controls were randomly chosen from all listed patients using the same time period and database used for the cases. We identified all patients listed for primary LT who did not die within 90 days of placement on the waiting list. As many as 3 control subjects were selected at random from the pool of all potential controls for each case subject matched by the following criteria:

Year of listing (within 4 years).

Age at listing (within 5 years).

Sex.

Liver disease etiology (hepatitis C virus, alcohol, hepatitis C virus with alcohol, other viral etiology, cholestatic/autoimmune etiology, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis/cryptogenic etiology, or other metabolic/genetic etiology).

Presence of hepatocellular carcinoma.

MELD score at listing (within 2 points of the lowest MELD score within 90 days of the case subject’s death).

No control subjects were used more than once. This study protocol received a priori approval by our institutional review board.

DATA COLLECTION

NLR, cirrhosis stage, serum sodium, serum albumin, jaundice (total bilirubin ≥3 mg/dL), and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) were assessed at date of lowest MELD within 90 days of death for cases and within 90 days after listing for controls.

We performed identical chart reviews of cases and controls. The observation period for cases was defined as the period between the lowest MELD score within 90 days of death and the death of the subject. For controls, the observation period started at the time of listing and ended 90 days after listing or at LT, whichever happened first. All MELD scores generated for a patient during the observation period were collected. We established baseline MELD scores for both cases and controls. For cases, the baseline MELD score was the lowest MELD score within 90 days of death. For controls, we used the listing MELD score as the baseline.

Two independent reviewers assessed charts for the history of varices, variceal bleeding, ascites, HE, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPSs) before the baseline MELD score for cases and at the end of the study period for controls (to allow for a full assessment of prevalent conditions). The top 3 causes of liver-related death among cases were also collected by independent chart review. Two independent chart reviewers assessed subjective variables, with discordant cases adjudicated by an expert reviewer.

The presence of ascites was ascertained in accordance with the International Ascites Club(26,27) and was graded as follows: grade 1 (radiographic evidence only), grade 2 (clinically apparent mild-to-moderate ascites), grade 3 (large ascites and/or paracentesis >3 L), or refractory (ascites resistant or intractable to medical therapy and requiring repeated large-volume paracentesis or TIPS). Large ascites was defined as physical examination findings describing tense, massive, large, or similarly described ascites or ascites requiring a paracentesis of at least 3 L. For the purpose of data analysis, at least grade 3 or refractory ascites was required for dichotomous variables.

The presence of varices was recorded as any grade documented on endoscopy and including esophageal, gastric, rectal, or small/large bowel varices. Variceal bleeding was defined as any chart or procedural documentation implicating varices as the source of gastrointestinal bleeding. HE was retrieved from clinical notes or from documentation of encephalopathy-modifying medications. Jaundice was defined as total bilirubin ≥3 mg/dL.

NLR was assessed at the date of lowest MELD: within 90 days of death for cases and within 90 days after listing for matched controls. Medication use, including the use of antibiotics and nonselective beta-blockers, was collected at the time of the lowest MELD score for cases and at the end of the follow-up period for controls. The cirrhosis stage(6,23) was determined at the date of the baseline MELD score for cases and at the end of the observation period for controls. It was determined with any history of varices, variceal bleeding, and ascites as defined previously. The definition of ascites for the assessment of the cirrhosis stage required a history of at least grade 3 or refractory ascites.

Two independent reviewers conducted detailed chart reviews to examine causes of death among cases, and they were coded as liver-related or non–liver-related according to a priori defined criteria as follows: bleeding, infection, sepsis, pulmonary complications (including pneumonia and pulmonary edema), acute renal failure, multiorgan failure, and neurological complications resulting from HE. A designation as a non–liver-related death required the absence of a dominant liver-associated cause and a clear non–liver-related cause of death such as acute myocardial infarction, accidental trauma-related death, stroke, or complications of procedures not directly related to care for the liver disease. A third independent reviewer adjudicated indeterminate causes of death. Patients with a non–liver-related death or insufficient information to determine the cause of death were excluded.

All serum albumin and sodium laboratory draws were collected during the observation periods. The albumin and sodium levels at the time of the baseline MELD score for cases and the lowest albumin and sodium levels during the controls’ observation period were identified and used for analysis.

FLOW CYTOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF LEUKOCYTES

Peripheral blood was drawn at a single time point on a separate cohort of 15 patients with cirrhosis who were listed for LT and seen in the University of Colorado Hepatology clinic (translational cohort described below). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Colorado Denver. Both written and oral consent was obtained before samples were collected. The translational cohort was 47% female; mean age was 52.5 years (range, 39–65 years); and subjects were predominantly Caucasian (80%). None had hepatocellular carcinoma. The median MELD score for this cohort was 15 (range, 9–20) at time of analysis. Multiparameter flow cytometry was performed using a BD fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Canto II instrument compensated with single fluorochromes and analyzed using Divasoftware (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Flurochrome-labeled (FITC/PE/PerCP/APC/APC-H7/V450/V500) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific for CD3, CD14, CD15, CD16, CD19, CD56, and CD45 were purchased from BD Biosciences. Anti-neutrophil elastase (NE) MAb was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Whole blood (100 μL) was stained for cell surface antigen expression at 4 °C in the dark for 30 minutes followed by red blood cell lysis and then washed twice in 2mL phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.01% sodium azide and acquired immediately. Intracellular staining for NE was performed following surface staining using the Intracellular Fixation and Permeabilization Buffer Set from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Isotype-matched fluorescently labeled control antibodies were used to determine background levels of staining. Results are expressed as % positive of gated populations. NE levels were expressed as the mean fluorescent intensity which corresponds directly to the number of molecules on a per cell basis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The listing MELD scores for cases and controls were compared using a mixed effect model to allow for the matching of cases to controls. Conditional logistic regression (to account for the matching of cases to controls) was conducted for all potential predictors of liver-related death. Variables that were significant in univariate modeling (P <0.10) were then entered into a multivariate model. Significance in the multivariate model was defined as P <0.05. NLR ≥4 was used as a predetermined cutoff based on prior studies.(18,20) In addition, the 25th, 50th, 75th percentile cutoffs for NLR were determined and analyzed in the univariate and multivariate models.

The cirrhosis stage was modeled both as a binary variable (eg, stage 5 versus stages 1–4) and as an ordinal variable (stage 1 versus stage 5) tested for trends. Serum sodium was also modeled as both a binary variable (<135 or ≥135 mEq/L) and as a continuous variable. Demographic variables not used for matching were compared using conditional logistic regression. The baseline characteristics of the cases and the patients excluded for deaths outside our hospital system were compared with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate, with the Cochran-Armitage trend test for stage comparisons, and with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for comparisons of ages and MELD scores between cases and excluded patients. SAS 9.3 was used for statistical analysis (SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC).

Results

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDY COHORT

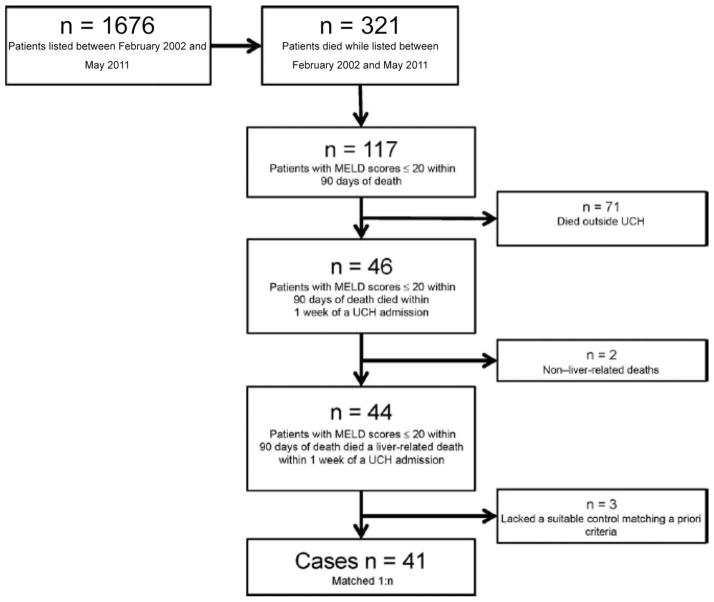

We identified 1676 patients who were listed for LT between February 2002 and May 2011. Figure 1 shows our patient acquisition flow diagram. The number of individuals who died while they were listed was 321, and 117 of those who died had a MELD score of 20 within 90 days of death. We excluded 71 patients because they died outside the UCH system, and we had insufficient records to assess the cause of death. Two additional patients were excluded because they had experienced non–liver-related deaths (1 due to accidental trauma and the other due to postsphincterotomy bleeding after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography). Three patients were excluded because they lacked suitable controls meeting the a priori matching criteria. Therefore, our study population included 41 case subjects with each matched to as many as 3 control subjects for a total of 66 controls.

FIG. 1.

Patient acquisition flow diagram.

Because cases could have up to 3 matched-controls, there were some expected imbalances in the demographics of the cases and controls. Table 2 summarizes the demographic data of the cases and controls. The mean ±standard deviation (SD) matching age cases was 57 ±5.8 years and for the controls was 55 ±5.4 years. The cases were 51% male, whereas the controls were 61% male. NLR was ≥4 in 25/41 (61%) cases and 17/66 (26%) controls. NLR 25th, 50th, 75th percentile cutoffs were 1.9, 3.1, and 6.8. Median (inter-quartile range [IQR]) NLR for cases and controls was 5.0 (3.0–10.3) and 2.4 (1.6–3.9).

TABLE 2.

Demographic Information on Cases and Controls

| Variable and Category | Case (n = 41) | Control (n = 66) | Total (n = 107) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex male | 21 (51) | 40 (60) | 61 (57) | NA* |

| Race | 0.67 | |||

| Caucasian | 29 (70) | 44 (67) | 73 (68) | |

| Hispanic | 10 (24) | 16 (24) | 26 (24) | |

| Other race | 2 (5) | 6 (9) | 8 (7) | |

| Etiology | NA* | |||

| Hepatitis C virus | 12 (29) | 24 (36) | 36 (34) | |

| Alcohol | 10 (24) | 11 (17) | 21 (20) | |

| Hepatitis C virus with alcohol | 7 (17) | 12 (18) | 19 (18) | |

| Cholestatic/autoimmune | 8 (20) | 11 (17) | 19 (18) | |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis/cryptogenic | 4 (10) | 7 (11) | 11 (10) | |

| Other metabolic/genetic | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| HCC | 3 (7) | 2 (3) | 5 (5) | NA* |

| Age, years | 57±6 | 55±5.4 | 55±5.6 | NA* |

| MELD used for matching | 16±3 | 15±3 | 16±2.9 | NA* |

| Median (IQR) | 17 (14–18) | 16 (13–17) | 16 (14–18) | |

| MELD at listing | 16±7 | 15±3 | 15±4.8 | 0.15 |

| Median (IQR) | 15 (13–19) | 16 (13–17) | 15 (13–18) | |

| NLR < 4 | 16 (39) | 49 (74) | 65 (61) | 0.001 |

| NLR ≥ 4 | 25 (61) | 17 (26) | 42 (39) | |

| Cirrhosis stage | 0.003† | |||

| 1 | 5 (12) | 19 (29) | 24 (22) | |

| 2 | 9 (22) | 31 (47) | 40 (37) | |

| 3 | 11 (27) | 6 (9) | 17 (16) | |

| 4 | 11 (27) | 8 (12) | 19 (18) | |

| 5 | 5 (12) | 2 (3) | 7 (7) |

NOTE: Data are given as n (%) or mean ±SD unless otherwise noted.

Matched on these variables.

Ordinal variable with a test for trend.

We assessed the variability of NLR over time. A mixed model on the continuous values of NLR over 3 discrete time points up to 3 months after listing, starting at listing and allowing for whether they were a case or a control, did not show a significant change over time (P =0.15). Cases and controls started at similar levels at listing, and there was no statistically significant interaction between case/control and time. A mixed model on the continuous values of NLR over 3 discrete time points from listing for the controls and within 2 months before or after the nadir MELD score prior to death for the cases, allowing for whether they were a case or a control, did show a significant change over time (P=0.003). This was due to the increase in NLR for the cases from the value 2 months prior to the nadir MELD score prior to death, but this remained higher in the 2 months after the nadir. NLR for the cases remained significantly higher over time than controls (P <0.001), but there was no statistically significant interaction between case/control and time.

More cases had reached higher stages of cirrhosis in comparison with controls (66% of cases were stage 3 or higher, compared with 24% of controls (Table 2). An infection from any source was one of the top 3 causes of death for 61% of the cases (Table 3). Sepsis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and pulmonary infections were implicated in the deaths of 49%, 15%, and 20% of the cases, respectively. Gastrointestinal bleeding from any source and variceal bleeding were implicated in the deaths of 29% and 24% of the cases, respectively. Acute renal failure of any cause and hepatorenal syndrome were implicated in the deaths of 32% and 22% of the cases, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Disease States Contributing to Liver-Related Deaths Among Cases

| Contributing Disease State | n = 41 |

|---|---|

| Any infection | 25 (61) |

| Sepsis | 20 (49) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 6 (15) |

| Pneumonia, empyema, or pulmonary abscess | 8 (20) |

| Any gastrointestinal bleeding | 12 (29) |

| Variceal bleeding | 10 (24) |

| Any acute renal failure | 13 (32) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 9 (22) |

NOTE: Data are given as n (%). Multiple contributing disease states could occur in each individual patient.

To examine the potential impact of excluding deaths outside our hospital system with incomplete details about the causes of death, we compared the demographic, laboratory, and clinical data of such patients to our identified cases. Supporting Table 1 compares the demographics of the case subjects in our study population to the 71 patients excluded for dying outside our hospital system. Because these patients all had routine care before their deaths, similar data were available for nearly all other data fields in comparison with the cases. There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the case subjects, and the patients who were excluded for deaths outside our hospital system.

In order to evaluate the controls for significant improvements or deterioration after listing, we collected their lowest and highest MELD scores over the observation period. The case and control median baseline MELD scores were 17 (IQR, 14–18) and 16 (IQR, 13–17), respectively, and this was consistent with effective matching. The median changes between the controls’ baseline MELD scores and their highest and lowest MELD scores during the observation period were 0 (IQR, 0–2) and 0 (IQR, 0–2), respectively, and this indicated minimal changes in the controls’ MELD scores throughout the observation period.

PREDICTORS OF DEATH WITH LOW MELD SCORES

Using our 1:n case-control study design, we assessed predictors of liver-related death in univariate analyses and then multivariate analyses. The results of the univariate analysis are shown in Table 4. Among the statistically significant univariate predictors of liver-related death were NLR (continuous, ≥1.9, ≥4, ≥6.8), prior variceal bleeding, prior or current grade 3 or refractory ascites, serum albumin, serum sodium, and increasing stage of cirrhosis, jaundice (total bilirubin ≥3 mg/dL), platelet count, nonselective beta-blocker use, xifaxan use, and other antibiotic use.

TABLE 4.

Univariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Liver-Related Mortality Among Patients With Low MELD Scores Listed for LT

| Variable | Cases (n = 41) | Controls (n = 66) | OR | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cirrhosis stages* | — | — | 0.003† | |

| Cirrhosis stage 5 versus stages 1–4 | 12 | 3 | 4.0 | 0.11 |

| Cirrhosis stage 4 and 5 versus stages 1–3 | 39 | 15 | 4.1 | 0.008* |

| Cirrhosis stage 3–5 versus stages 1–2 | 66 | 24 | 7.4 | <0.001* |

| Cirrhosis stage 2–5 versus stages 1 | 88 | 71 | 3.6 | 0.048* |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.5±0.7 | 2.8±0.6 | 0.5 | 0.041* |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 133±4 | 135±5 | 0.9 | 0.051* |

| Sodium <135, mmol/L | 71 | 41 | 3.4 | 0.006* |

| NLR | 9.6±10.0 | 4.3±8.3 | 1.1 | 0.029 |

| NLR ≥1.9 | 93 | 67 | 13.5 | 0.012 |

| NLR ≥4 | 61 | 26 | 5.3 | 0.001 |

| NLR ≥6.8 | 49 | 12 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Varices | 76 | 67 | 1.5 | 0.36 |

| Variceal bleeding | 39 | 12 | 5.6 | 0.003* |

| Ascites | 39 | 15 | 4.1 | 0.008* |

| HE | 83 | 70 | 2.3 | 0.08* |

| TIPS | 17 | 7.6 | 2.3 | 0.22 |

| Jaundice | 56 | 42 | 3.6 | 0.032* |

| Xifaxan‡ | 32 | 11 | 13.1 | 0.015* |

| Other antibiotics | 12 | 21 | 0.48 | 0.22 |

| Nonselective beta-blockers | 34 | 15 | 3.3 | 0.027* |

| Platelets | 83±65 | 100±69 | 1.0 | 0.14 |

NOTE: Data are given as a percentage, mean ±SD.

Statistically significant in the univariate analysis (P =0.01).

Ordinal variable with a test for trend.

Too few events to be included in multivariate model (20 patients with Xifaxan, 13 cases and 7 controls, models did not converge).

In a multivariate model including the NLR as an ordinal variable tested for trend, cirrhosis stage, serum albumin, serum sodium, and HE, as well as jaundice (total bilirubin ≥3 mg/dL) and nonselective beta-blocker use, NLR (≥4, ≥6.8) remained significant (P =0.023; P =0.004; Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Liver-Related Mortality Among Patients With Low MELD Scores Listed for LT

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| OR | P Value | OR | P Value | OR | P Value | |

| NLR | 8.1 (for NLR >= 1.9) | 0.07 | 4.4 (for NLR >= 4) | 0.023 | 17.0 (for NLR >= 6.8) | 0.004 |

| Increasing cirrhosis stage* | 0.039 | 0.032 | 0.049 | |||

| Sodium | 1.0 | 0.59 | 1.0 | 0.74 | 1.0 | 0.85 |

| Albumin | 0.7 | 0.50 | 0.6 | 0.34 | 0.4 | 0.15 |

| HE | 1.2 | 0.77 | 1.5 | 0.59 | 1.9 | 0.51 |

| Jaundice | 5.1 | 0.039 | 5.2 | 0.047 | 6.9 | 0.045 |

| Beta-blockers | 2.0 | 0.39 | 1.6 | 0.54 | 2.0 | 0.42 |

Ordinal variable with a test for trend.

NLR CORRELATES WITH HIGHER FREQUENCY OF PROINFLAMMATORY NEUTROPHILS IN TRANSLATIONAL COHORT

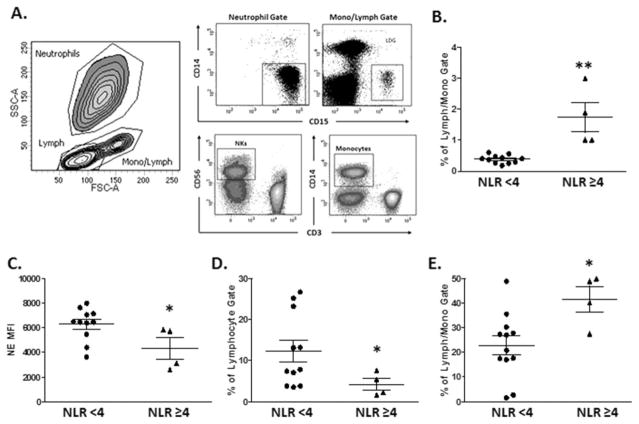

Next, in an effort to more clearly define if higher NLR was associated with specific subsets of neutrophils, we characterized the frequency of low-density granulocytes (LDGs), previously identified as displaying proinflammatory properties, including induction of endothelial damage in other human diseases(28) in a separate translational cohort of 15 patients listed for LT with cirrhosis (demographics described in above in methods). Figure 2A shows the gating strategy used to stain freshly isolated neutrophils along with other peripheral blood mononuclear cell (see Patients and Methods). We found statistically higher frequencies of LDGs among patients with NLR >4, and we found that FACS and clinical laboratory estimations of NLR were highly correlated. Consistent with the concept that NLR ≥4 is associated with greater inflammation, we found lower levels of intracellular elastase within neutrophils, as would be expected following effector function. Moreover, we also found that patients with NLR ≥4 had higher circulating levels of monocytes and lower levels of natural killer (NK) cells. Taken together, these data indicate that NLR is a surrogate marker for immune dysregulation that may account for the higher mortality in our study patients.

FIG. 2.

NLR correlates to proinflammatory neutrophils. Lymphocytes (lymph), neutrophils, and monocytes (mono/lymph) were identified by characteristic high, medium, and low FSC and SSC parameters. Populations of interest were gated on positive staining for cell-specific antigen expression within the gated populations. Conventional neutrophils and LDGs are identified as CD14-CD15 +within the overall neutrophil or mono/lymph gates, respectively. (A) NK cells are identified as CD3-CD56 +cells within the lymph gate and monocytes as CD14 +cells within the mono/lymph gate. (B) LDG levels are increased in subjects with an NLR ≥4, and (C) their conventional neutrophils express lower levels of NE. (D) An NLR ≥4 is accompanied by a decreased proportion of NK cells and (E) an increase in monocytes. *<0.05; **P <0.005 Mann-Whitney U test.

We also assessed the variability of NLR over time in this separate cohort. A mixed model on the continuous values of NLR over time, taking into account the time between assessments and whether the last value was ≥4 did not show a significant change over time (P =0.78). Patients whose last value was ≥4 remained significantly higher over time than those whose last values were <4 (P =0.001). There was no statistically significant interaction between patient categories (last value ≥4 versus <4) and time.

Discussion

This study offers a novel finding with potential to positively influence LT wait-list prioritization. In 2014, Wedd et al.(6) demonstrated that an increasing cirrhosis stage was a risk factor for 90-day mortality in a tertiary care patient population, and specifically, that increasing cirrhosis stage was an independent predictor of death among patients listed for LT with MELD ≤20. Our results here indicate that, in addition to cirrhosis stage, a simple and objective calculation of the NLR ratio in LT candidates can have important clinical prognostic outcomes for the low MELD wait-list population. Specifically, we found that an elevated NLR was associated with liver-related death, independent of MELD and cirrhosis stage. Prior research has demonstrated that NLR is a predictor of mortality, independent of Child-Turcotte-Pugh and MELD, for patients with stable liver cirrhosis.(19) Our study advances this discussion by focusing on a low MELD (≤20) cohort of candidates listed for LT, while also controlling for cirrhosis stage.

This finding bolsters the evolving literature exploring independent predictors of death among LT candidates, as well as the literature examining NLR itself. Neutrophils are the most abundant immune cell population in the body, functioning as “first responders” for detection of invading pathogens.(29) Classical neutrophil effector functions include release of granular contents, cytokines, reactive oxygen species production, and release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that capture bacteria.(30) During sepsis, neutrophils migrate to liver sinusoids and release NETs,(31) adhere to platelets, and contribute significantly to hepatic pathology.

NLR reflects systemic inflammation as well as immune dysregulation and has previously been shown to predict prognosis in stable patients (ie, without acute decompensation) with end-stage cirrhosis listed for LT.(20) It has been postulated that this prognostic ability of NLR reflects multiple pathways of the pathophysiology underlying chronic liver disease including induction of low-dose endotoxinemia, which in turn results in a deleterious systemic inflammatory response in patients with cirrhosis.(20,32) As a result of such systemic inflammation, the intestinal barrier in patients with cirrhosis is compromised. In addition, there may be a qualitative functional defect of neutrophils in patients with cirrhosis—beyond their mere ratio to lymphocytes—contributing to poor outcomes such as infection, organ failure, and mortality.(33) Indeed, our data point to NLR as a useful marker for immune dysregulation (higher frequency of LDGs and monocytes, and lower circulating NK cells) that may account for the higher mortality in patients with cirrhosis.

Practically, NLR represents an easily accessible objective parameter, much like the 3 laboratory variables that are used to calculate the MELD score itself. As such, NLR is an important emerging variable that can be readily calculated and used by clinicians to inform their understanding of patients with MELD ≤20—a population that we know has a mortality underestimated by MELD alone. A high calculated NLR (≥4) may therefore aid in determining risk for cirrhotic decompensation, need for increased monitoring or prophylactic antimicrobial coverage, and urgency for expedited LT in candidates with low MELD.

The importance of identifying patients with low MELD who are likely to benefit from expedited LT cannot be understated, especially at a time when even during the MELD era, over 1500 candidates each year die on the transplant list.(24) Clearly, the ongoing supply-demand disparity in the United States increases the urgency for the LT community to better understand and identify candidates whose mortality is currently underestimated by conventional methods.

Indeed, realizing that these conventional methods underestimate mortality, several objective, prognostic biomarkers have been explored. These include C-reactive protein (CRP), serum free cortisol, and vitamin D, all of which may—like NLR—reflect systemic inflammatory stress.(34) However, all 3 of these are potentially confounded by liver disease itself because the liver is involved physiologically in the production of CRP, in the production of carrying proteins for cortisol, and in hydroxylation of vitamin D. NLR, in contrast, reflects a peripheral inflammatory response and therefore may be a more appropriate biomarker. Furthermore, our study results suggest a role for NLR as an adjunct to clinical decision-making involving patients with low MELD awaiting transplant.

Realizing that NLR may serve as an objective predictor of serious decompensation or liver-related death, the potential clinical implications include increased surveillance and monitoring practices for low MELD patients awaiting LT who have high (≥4) NLR. In addition, since low MELD patients are naturally given lower priority in the current MELD-based allocation and distribution system for deceased donation LT in the United States, a high NLR in these patients may guide clinicians to consider living donor or extended criteria donors for these patients.

This was a single-site study performed at a tertiary care facility, but we believe that the results of this study are applicable to any LT program and to the significant population of patients awaiting LT whose MELD is <20. In our analysis, we used the 2010 definitions of D’Amico’s cirrhosis stages,(23) but future studies may compare NLR’s predictive ability to the updated definitions.(35) Notably, we chose a nested case-control study design, rather than a prospective or retrospective cohort study, to account for the relatively rare outcome of a low MELD death. A 1:n matching protocol was used to increase the power of our study, and the resulting imbalance in baseline demographics was mitigated by conditional logistic regression analysis.

In addition, although our findings suggest a significant association between elevated NLR and mortality, we can currently only speculate on the mechanism underlying this finding. Future directions to explore this question further may include examining bacterial DNA in patients with low and high NLR, and also in low MELD patients over time. Pharmacologic intervention that alters the NLR, eg, with antibiotics or immunomodulation, may also advance the discussion regarding a potential mechanism to explain the ability of elevated NLR to independently predict mortality.

In summary, our results support the use of the NLR as an additional prognostic tool with a strong association with death, even after controlling for MELD and stage of cirrhosis (and several other plausible confounders). Importantly, NLR is readily available, objective, and, in our study, reliable over time, making it an ideal marker to risk-stratify LT candidates for increased monitoring and expedited pathways to transplant such as living donor LT or other extended criteria donor livers. Although cirrhosis has been long-characterized by neutrophil dysfunction, these data support the possibility that relatively increased circulation of these cells (particularly, the proinflammatory subset) may be a harbinger for poor outcome and warrant further translational investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Hugo R. Rosen is supported by VA Merit grant.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

View this article online at wileyonlinelibrary.com.

References

- 1.Said A, Williams J, Holden J, Remington P, Gangnon R, Musat A, Lucey MR. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score predicts mortality across a broad spectrum of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;40:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, Harper A, Kim R, Kamath P, et al. for United Network for Organ Sharing Liver Disease Severity Score Committee. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:91–96. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freeman RB, Wiesner RH, Edwards E, Harper A, Merion R, Wolfe R for United Network for Organ Sharing Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Liver and Transplantation Committee. Results of the first year of the new liver allocation plan. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:7–15. doi: 10.1002/lt.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biggins SW, Bambha K. MELD-based liver allocation: who is underserved? Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:211–220. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wedd J, Bambha KM, Stotts M, Laskey H, Colmenero J, Gralla J, Biggins SW. Stage of cirrhosis predicts the risk of liver-related death in patients with low Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores and cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1193–1201. doi: 10.1002/lt.23929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwong AJ, Lai JC, Dodge JL, Roberts JP. Outcomes for liver transplant candidates listed with low model for end-stage liver disease score. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:1403–1409. doi: 10.1002/lt.24307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huo TI, Lin HC, Lee FY, Hou MC, Lee PC, Wu JC, et al. Occurrence of cirrhosis-related complications is a time-dependent prognostic predictor independent of baseline model for end-stage liver disease score. Liver Int. 2006;26:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somsouk M, Kornfield R, Vittinghoff E, Inadomi JM, Biggins SW. Moderate ascites identifies patients with low model for end-stage liver disease scores awaiting liver transplantation who have a high mortality risk. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:129–136. doi: 10.1002/lt.22218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heuman DM, Abou-Assi SG, Habib A, Williams LM, Stravitz RT, Sanyal AJ, et al. Persistent ascites and low serum sodium identify patients with cirrhosis and low MELD scores who are at high risk for early death. Hepatology. 2004;40:802–810. doi: 10.1002/hep.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggins SW, Kim WR, Terrault NA, Saab S, Balan V, Schiano T, et al. Evidence-based incorporation of serum sodium concentration into MELD. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1652–1660. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biggins SW, Rodriguez HJ, Bacchetti P, Bass NM, Roberts JP, Terrault NA. Serum sodium predicts mortality in patients listed for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:32–39. doi: 10.1002/hep.20517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, Wiesner RH, Kamath PS, Benson JT, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1018–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thabut D, Massard J, Gangloff A, Carbonell N, Francoz C, Nguyen-Khac E, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease score and systemic inflammatory response are major prognostic factors in patients with cirrhosis and acute functional renal failure. Hepatology. 2007;46:1872–1882. doi: 10.1002/hep.21920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cazzaniga M, Dionigi E, Gobbo G, Fioretti A, Monti V, Salerno F. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome in cirrhotic patients: relationship with their in-hospital outcome. J Hepatol. 2009;51:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhat T, Teli S, Rijal J, Bhat H, Raza M, Khoueiry G, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cardiovascular diseases: a review. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;11:55–59. doi: 10.1586/erc.12.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guthrie GJ, Charles KA, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:218–230. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Templeton AJ, McNamara MG, Šeruga B, Vera-Badillo FE, Aneja P, Ocaña A, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju124. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biyik M, Ucar R, Solak Y, Gungor G, Polat I, Gaipov A, et al. Blood neutrophil–to-lymphocyte ratio independently predicts survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:435–441. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835c2af3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leithead JA, Rajoriya N, Gunson BK, Ferguson JW. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts mortality in patients listed for liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2015;35:502–509. doi: 10.1111/liv.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motomura T, Shirabe K, Mano Y, Muto J, Toshima T, Umemoto Y, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio reflects hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation via inflammatory microenvironment. J Hepatol. 2013;58:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue TC, Zhang L, Xie XY, Ge NL, Li LX, Zhang BH, et al. Prognostic significance of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D’Amico G, Villanueva C, Burroughs A, Dollinger MA, Planas R, Sola R, et al. Clinical stages of cirrhosis: A multicenter cohort study of 1858 patients. Hepatology. 2010;52:330A. [Google Scholar]

- 24.OPTN/UNOS. [Accessed November 5, 2016];Redesigning liver distribution to reduce variation in access to liver transplantation: A concept paper form OPTN/UNOS Liver and Intestine Organ Transplantation Committee. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/1269/liver_concepts_2014.pdf.

- 25.D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44:217–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;53:397–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, et al. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003;38:258–266. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denny MF, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Thacker SG, Anderson M, Sandy AR, et al. A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. J Immunol. 2010;184:3284–3297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, Metzler KD, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:459–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan MJ, Radic M. Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2012;189:2689–2695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp BG, Jenne CN, Kubes P. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krogh-Madsen R, Møller K, Dela F, Kronborg G, Jauffred S, Pedersen BK. Effect of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia on the response of IL-6, TNF-alpha, and FFAs to low-dose endotoxemia in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E766–E772. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00468.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu R, Huang H, Zhang Z, Wang FS. The role of neutrophils in the development of liver diseases. Cell Mol Immunol. 2014;11:224–231. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Martino V, Weil D, Cervoni JP, Thevenot T. New prognostic markers in liver cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1244–1250. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i9.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Amico G, Pasta L, Morabito A, D’Amico M, Caltagirone M, Malizia G, et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: a 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1180–1193. doi: 10.1111/apt.12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.