ABSTRACT

Although multiple restriction factors have been shown to inhibit HIV/SIV replication, little is known about their expression in vivo. Expression of 45 confirmed and putative HIV/SIV restriction factors was analyzed in CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood and the jejunum in rhesus macaques, revealing distinct expression patterns in naive and memory subsets. In both peripheral blood and the jejunum, memory CD4+ T cells expressed higher levels of multiple restriction factors compared to naive cells. However, relative to their expression in peripheral blood CD4+ T cells, jejunal CCR5+ CD4+ T cells exhibited significantly lower expression of multiple restriction factors, including APOBEC3G, MX2, and TRIM25, which may contribute to the exquisite susceptibility of these cells to SIV infection. In vitro stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies or type I interferon resulted in upregulation of distinct subsets of multiple restriction factors. After infection of rhesus macaques with SIVmac239, the expression of most confirmed and putative restriction factors substantially increased in all CD4+ T cell memory subsets at the peak of acute infection. Jejunal CCR5+ CD4+ T cells exhibited the highest levels of SIV RNA, corresponding to the lower restriction factor expression in this subset relative to peripheral blood prior to infection. These results illustrate the dynamic modulation of confirmed and putative restriction factor expression by memory differentiation, stimulation, tissue microenvironment and SIV infection and suggest that differential expression of restriction factors may play a key role in modulating the susceptibility of different populations of CD4+ T cells to lentiviral infection.

IMPORTANCE Restriction factors are genes that have evolved to provide intrinsic defense against viruses. HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) target CD4+ T cells. The baseline level of expression in vivo and degree to which expression of restriction factors is modulated by conditions such as CD4+ T cell differentiation, stimulation, tissue location, or SIV infection are currently poorly understood. We measured the expression of 45 confirmed and putative restriction factors in primary CD4+ T cells from rhesus macaques under various conditions, finding dynamic changes in each state. Most dramatically, in acute SIV infection, the expression of almost all target genes analyzed increased. These are the first measurements of many of these confirmed and putative restriction factors in primary cells or during the early events after SIV infection and suggest that the level of expression of restriction factors may contribute to the differential susceptibility of CD4+ T cells to SIV infection.

KEYWORDS: CD4+ T lymphocytes, gut-associated lymphoid tissue, interferon-stimulated genes, restriction factors, simian immunodeficiency virus

INTRODUCTION

Restriction factors serve as a key host defense against virus infection. Many of these genes have well-described activity against the primate lentiviruses HIV and SIV, including the APOBEC3 DNA deaminase family (1), the TRIM family (2), BST-2/tetherin (3, 4), and SAMHD1 (5). In addition to the more well-studied restriction factors, screens have been performed to identify additional restriction factors. A whole-genome small interfering RNA screen has identified putative restriction factors such as the PAF1 complex and exosome components (6). A screen for genes sharing genomic characteristics of known restriction factors identified APOL and TNFRSF family members and used cell-based assays to confirm the restriction of HIV-1 (7). Although many studies focus on the impact of a single factor, the total effect of restriction factors on virus infection is likely to be cumulative. Though much work has focused on defining mechanisms of action and structure-function studies for individual restriction factors, little is known about the levels of expression in primary CD4+ T cells and how expression may be modulated as a result of T cell differentiation and activation or during the course of acute lentiviral infection.

Naive CD4+ T cells that are stimulated by cognate antigen can differentiate into a broad range of functionally specialized cell subsets (8). Studies have found that the differentiation status of a CD4+ T cell influences its susceptibility to HIV and SIV infection and, specifically, that memory CD4+ T cells are more likely to be infected than naive CD4+ T cells (9, 10). The effects of memory differentiation on restriction factor expression are incompletely understood and may contribute to the differential susceptibility of memory and naive cells.

During acute infection, HIV and SIV primarily replicate in and deplete gut CD4+ T cells (11–13); however, primary cells from mucosal tissues are relatively understudied compared to cells from peripheral blood due to the difficulty in obtaining tissue samples (14). Whether expression of restriction factors differs between peripheral blood CD4+ T cells, which are infected at lower rates, and CD4+ T cells in the gut mucosa, which are highly susceptible to SIV/HIV infection (11–13), is currently unknown. We studied here the expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in CD4+ T cells obtained from the jejunum as a representative gut mucosal site; the jejunum was chosen due to the relative abundance of jejunal lymphoid cells compared to other intestinal regions, the relative infrequency of immune inductive sites in this location (15), and the availability of robust data sets regarding the kinetics of SIV replication in the jejunum (11–13).

The events of acute immunodeficiency virus infection are challenging to study in humans. Analysis of acute lentiviral infection in nonhuman primates has multiple advantages, including the ability to control the inoculating strain, the precise timing of sampling, and superior access to mucosal and lymphoid tissues. In light of strong evidence documenting the induction of interferon during primary SIV and HIV infection and the fact that many restriction factors are known to be interferon (IFN)-stimulated genes (ISGs) (16, 17), we reasoned that expression of restriction factors is likely to be modulated during the course of SIV infection. However, data on the modulation of expression of restriction factors in different CD4+ T cell subsets during acute SIV infection, especially for the critical CD4+ target cells in the gut mucosa, is not currently defined.

We hypothesized that the comprehensive analysis expression of a large panel of confirmed and putative restriction factors would provide insights into the molecular mechanisms that underlie differences between naive and memory cells in their susceptibility to lentiviral infection, as well as the differential infectivity between peripheral blood and gut mucosa CD4+ T cells. Analysis of expression of target genes was performed using a high-throughput microfluidic RT-PCR platform that allows for highly quantitative and specific analysis of up to 96 genes at a time from each of 96 samples. Using highly purified sorted populations of CD4+ T cells, we observed both up- and downregulation of restriction factors due to memory differentiation that occurred in a similar pattern in both peripheral blood and jejunum cells. Stimulation with either anti-CD3/CD28 or type I IFN also altered expression of restriction factors in primary cells. Despite broad similarities in expression patterns between peripheral blood and the jejunum, the transitional memory CD4+ T cells from the jejunum had lower total expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors relative to the same subset in peripheral blood. After infection with SIVmac239, transitional memory CD4+ T cells from the jejunum exhibited the highest level of infection. Strikingly, expression of most restriction factors increased in all memory subsets during acute SIV infection.

RESULTS

Expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in peripheral blood CD4+ T cells.

As a comprehensive approach to analyze the expression of restriction factors in primary CD4+ T cells, a list of 45 confirmed or putative HIV/SIV restriction factors was compiled from published sources (Table 1). (We refer to these molecules as restriction factors in the remainder of the manuscript but acknowledge that a number of these molecules have not been rigorously confirmed as restriction factors). To assess expression of restriction factors in defined cell populations in macaques not infected with SIV, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and jejunum lymphocytes were isolated from four Indian-origin rhesus macaques, stained with monoclonal antibodies, and sorted into four highly purified populations: naive (CD3+4+28+95− CCR7+ CCR5−), central memory (CD3+4+28+95+ CCR7+ CCR5−), transitional memory (CD3+4+28+95+ CCR7− CCR5+), and effector memory (CD3+4+28−95+ CCR7− CCR5−) (18, 19). RNA was extracted and the cDNA samples were analyzed on the Fluidigm BioMark microfluidic real-time PCR system.

TABLE 1.

Confirmed and putative restriction factors selected for analysisa

| Gene | ENTREZ ID |

HGNC full name | Assay ID | Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macaque | Human | ||||

| APOBEC3A | 702708 | 200315 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3A | Rh04329459_m1 | 42, 43 |

| APOBEC3C | 705870 | 27350 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3C | Rh03418653_s1 | 42 |

| APOBEC3D | 705996 | 140564 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3D | Custom | 42, 44 |

| APOBEC3F | 723812 | 200316 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3F | Rh04256581_s1 | 42, 44 |

| APOBEC3G | 574398 | 60489 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3G | Rh02788475_m1 | 42, 44, 45 |

| APOBEC3H | 723811 | 164668 | Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3H | Rh04256315_m1 | 42, 44 |

| APOL1 | 694508 | 8542 | Apolipoprotein L, 1; APOL; APO-L; FSGS4; APOL-I | Custom | 46, 47 |

| APOL6 | 693593 | 80830 | Apolipoprotein L, 6 | Custom | 7, 47, 48 |

| BST2 | 719092 | 684 | CD317; NPC-A-7; bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2; tetherin | Rh02848328_m1 | 3, 4 |

| CD164 | 699242 | 8763 | CD164 molecule, sialomucin | Rh02859344_m1 | 7 |

| CDKN1A | 719199 | 1026 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) | Hs00355782_m1 | 49, 50 |

| CTR9 | 705748 | 9646 | Ctr9, Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex component, homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Rh02792191_m1 | 6 |

| EXOSC10 | 714153 | 5394 | Exosome component 10 | Rh00897424_m1 | 6 |

| EXOSC2 | 715960 | 23404 | Exosome component 2 | Rh02930061_mH | 6 |

| EXOSC3 | 716347 | 51010 | Exosome component 3 | Rh02830694_m1 | 6 |

| GSN | 699705 | 2934 | Gelsolin (amyloidosis, Finnish type) | Rh02794823_m1 | 51 |

| HERC5 | 702743 | 51191 | Hect domain and RLD 5 | Custom | 52 |

| IFITM1 | 697687 | 8519 | IFN-induced transmembrane protein 1 (9-27) | Rh02809735_gH | 53 |

| IFITM3A | 697829 | 10410 | IFN-induced transmembrane protein 3-like (predicted) | Custom | 53 |

| IFITM3B | 697564 | 10410 | IFN-induced transmembrane protein 3-like (predicted) | Custom | 53 |

| ISG15 | 700141 | 9636 | ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier | Rh02915441_g1 | 52 |

| MICB | 715141 | 4277 | MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence B | Rh02787686_m1 | 47 |

| MOV10 | 705910 | 4343 | Mov10, Moloney leukemia virus 10, homolog (mouse) | Rh02878489_m1 | 54, 55, 79 |

| MX2 | 780935 | 4600 | Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 (mouse) | Rh02801425_m1 | 56, 57 |

| PAF1 | 697786 | 54623 | Paf1, RNA polymerase II-associated factor, homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Rh02876261_m1 | 6 |

| PARP1 | 698806 | 142 | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 | Rh00911359_m1 | 58 |

| PRMT6 | 694284 | 55170 | Protein arginine methyltransferase 6 | Rh02817860_s1 | 59, 60 |

| RPRD2 - REAF | 715526 | 23248 | Regulation of nuclear pre-mRNA domain containing 2; REAF | Rh02868968_m1 | 6, 61 |

| RTF1 | 706200 | 23168 | Rtf1, Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex component, homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Rh01025583_m1 | 6 |

| SAMHD1 | 709060 | 25939 | SAM domain and HD domain 1 | Rh02869977_m1 | 5, 62 |

| SETDB1 | 716141 | 9869 | SET domain, bifurcated 1 | Rh02803155_m1 | 6 |

| SLFN11 | 715511 | 91607 | Schlafen family member 11 | Rh02885088_m1 | 63 |

| SLFN14 | 718850 | 342618 | Schlafen family member 14 | Custom | |

| TNFRSF10A | 716826 | 8797 | TNF receptor superfamily, member 10a | Rh02846752_m1 | 7 |

| TNFRSF10D | 8793 | 8793 | TNF receptor superfamily, member 10d, decoy with truncated death domain | Rh02846723_m1 | 7 |

| TRIM14 | 715418 | 9830 | Tripartite motif-containing 14 | Custom | 47 |

| TRIM19 - PML | 700379 | 5371 | Promyelocytic leukemia | Rh03043124_m1 | 64 |

| TRIM22 | 713814 | 10346 | Tripartite motif-containing 22 | Rh02801450_m1 | 65, 66, 80 |

| TRIM25 | 712588 | 7706 | Tripartite motif-containing 25 | Rh02856605_m1 | 6 |

| TRIM26 | 100141397 | 7726 | Tripartite motif-containing 26 | Rh03418272_m1 | 67 |

| TRIM28 | 711982 | 10155 | Tripartite motif-containing 28 | Rh01076235_m1 | 68 |

| TRIM32 | 702595 | 22954 | Tripartite motif-containing 32 | Custom | 69 |

| TRIM34 | 100568287 | 53840 | TRIM6-TRIM34 readthrough transcript; tripartite motif-containing 6; tripartite motif-containing 34 | Rh04256228_m1 | 70 |

| TRIM38 | 694861 | 10475 | Tripartite motif-containing 38 | Rh02860500_m1 | 67 |

| TRIM5_3_4 | 574288 | 85363 | Tripartite motif containing 5; exon 3-4 junction, all isoforms | Rh02788627_m1 | 22, 71 |

| TRIM5A_7_8 | 574288 | 85363 | Tripartite motif containing 5; exon 7-8 junction, alpha isoform only | Rh02788631_m1 | 22, 71 |

| ZC3H12A | 713604 | 80149 | Zinc finger CCCH-type containing 12A; MCPIP1 | Rh02882632_mH | 72 |

Assay ID numbers are provided for the ABI TaqMan assays; sequences for the custom assays are provided in the text.

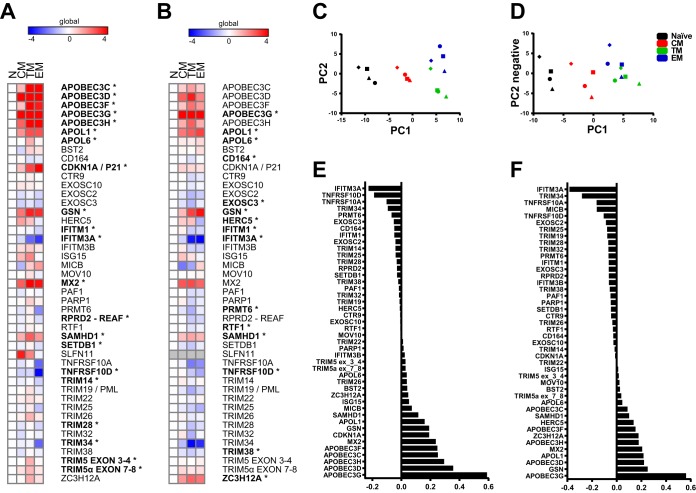

Results from each animal were normalized by the ΔΔCT method (20) to the most stable of seven endogenous control genes (POLR2A), as determined by the NormFinder algorithm (21), and to the naive population (Fig. 1A). In general, increased expression was seen for many of the target genes in memory subsets relative to naive cells, including APOBEC family members, p21, GSN, and SAMHD1. The CCR5+ transitional memory CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood expressed the largest number of confirmed and putative restriction factors, 12, with a mean of at least 4-fold greater expression relative to naive cells compared to nine genes in effector memory and six in central memory.

FIG 1.

Confirmed and putative restriction factors exhibit similar patterns of expression in peripheral blood and jejunum CD4+ T cell memory subsets and are dynamically modulated by stimulation. (A and B) Heat map of −ΔΔCT expression values depicting memory subset expression relative to naive for peripheral blood (A) and the jejunum (B). POLR2A was used as endogenous control gene for normalization. The means for four animals are shown (*, P < 0.01 [repeated-measures ANOVA with an extension of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method]). (C and D) PCA for peripheral blood (C) and the jejunum (D) based on analysis of 45 restriction factor genes. Each symbol in panels C and D represents a different animal. (E and F) PC1 loading factors from the PCA for peripheral blood (E) and the jejunum (F).

Using expression data of only the restriction factor genes normalized to a stable control gene (POLR2A), principal-component analysis (PCA) revealed expression patterns that clustered by memory subset (Fig. 1E). Since each memory subset was more similar to the respective subset from another animal rather than other subsets from the same animal (Fig. 1C and D), these data reveal a reproducible pattern of expression due to memory differentiation. Examination of the loading factors for principal component axis 1 (PC1) identified the genes driving the clustering along the x axis. APOBEC family members, MX2, GSN, and TNFSRF family members were the major genes contributing to memory subset differences. These genes were among the most differentially expressed restriction factors among memory populations.

Expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in jejunum CD4+ T cells.

CD4+ T cells from the jejunum showed a similar pattern of restriction factor expression as observed in peripheral blood CD4+ T cells, demonstrating that in general, expression of restriction factors was modulated primarily by memory differentiation regardless of tissue location (Fig. 1B). Similar to peripheral blood, transitional memory cells had the largest number of upregulated target genes—eight, relative to naive cells, compared to four in central memory and five in effector memory. As in peripheral blood, PCA also clustered memory subsets together for jejunum CD4+ T cells, though transitional and effector memory cells were not as distinctly separated (Fig. 1D). Similar genes contributed to the spatial organization of samples along PC1, including APOBECs, MX2, GSN, and TNFRSF genes (Fig. 1F).

Since TRIM5 is known to be expressed as multiple differentially spliced isoforms where only the α isoform is restrictive (22), we used two assays for TRIM5: one that recognizes a splice junction present in all TRIM5 transcripts (exon 3-4) and one that recognizes the exon 7-8 splice junction found only in TRIM5α. This allowed assessment of the precise functional isoform in case it differed in expression under the various tested conditions. In both peripheral blood and the jejunum, both TRIM5 assays showed similar patterns of expression change relative to naive CD4+ T cells, indicating that the transcript levels are not differentially affected by memory differentiation.

Stimulation alters expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors.

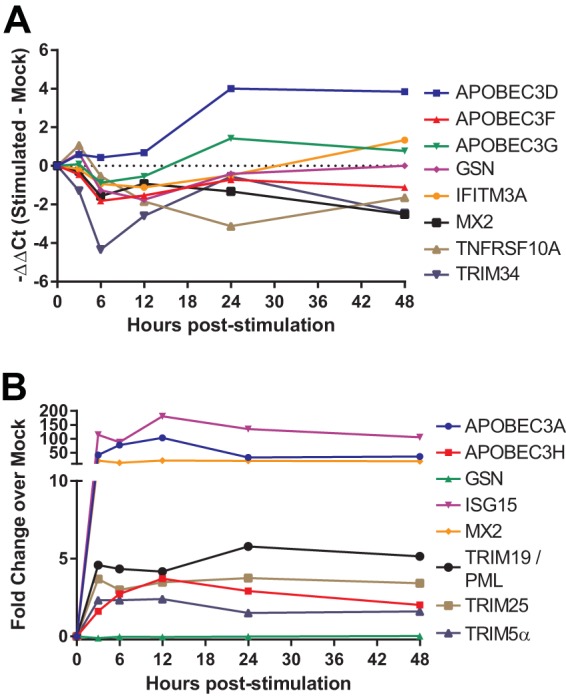

To test whether cellular activation modulated expression of the target genes, bulk CD4+ T cells were isolated from the peripheral blood of four rhesus macaques and stimulated with either αCD3/αCD28-coupled beads or recombinant type I human IFN-αA/D. CD3/CD28 activation significantly (P < 0.05, t test) modulated 36% of the genes in at least one time point compared to mock-stimulated cells (Fig. 2A). Stimulation induced both increases and decreases in expression of multiple restriction factors over the course of the experiment, showing that restriction factor expression can be dynamically modulated by CD3/CD28 stimulation. This pattern of modulation of expression of restriction factors contrasts with that previously observed in response to phytohemagglutinin (PHA) stimulation, which generally resulted in increased restriction factor expression in human CD4 T cells (23).

FIG 2.

Expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors is dynamically modulated by CD3/CD28 and type I IFN stimulation. (A) Time course of the change in expression of selected restriction factor genes in CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads versus mock-treated animals relative to the time of stimulation. (B) Time course of the change in expression of restriction factor genes after stimulation with 1,000 U of type I IFN/ml relative to the time of stimulation. Data represent the means of samples obtained from four animals. The results shown for TRIM5α reflect data obtained using an assay specific for the α isoform of TRIM5.

In vitro IFN stimulation increased expression of 32% of the genes compared to mock-stimulated cells (Fig. 2B). All of the restriction factors exhibiting increased expression have been previously found to be IFN-stimulated genes in microarray studies (24–26). The time course exhibited a rapid modulation of responding genes as they reached peak or near-peak fold changes by the earliest time point poststimulation, 3 h, and generally maintained these levels for 48 h. Similar to memory differentiation, both TRIM5 assays were modulated in concert by interferon, indicating similar regulation of the different transcripts. Overall, both forms of stimulation showed that restriction factor expression can be dynamically modulated by external signals; however, neither form of stimulation reproduced a pattern similar to memory differentiation.

Differences between expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in the jejunum and peripheral blood.

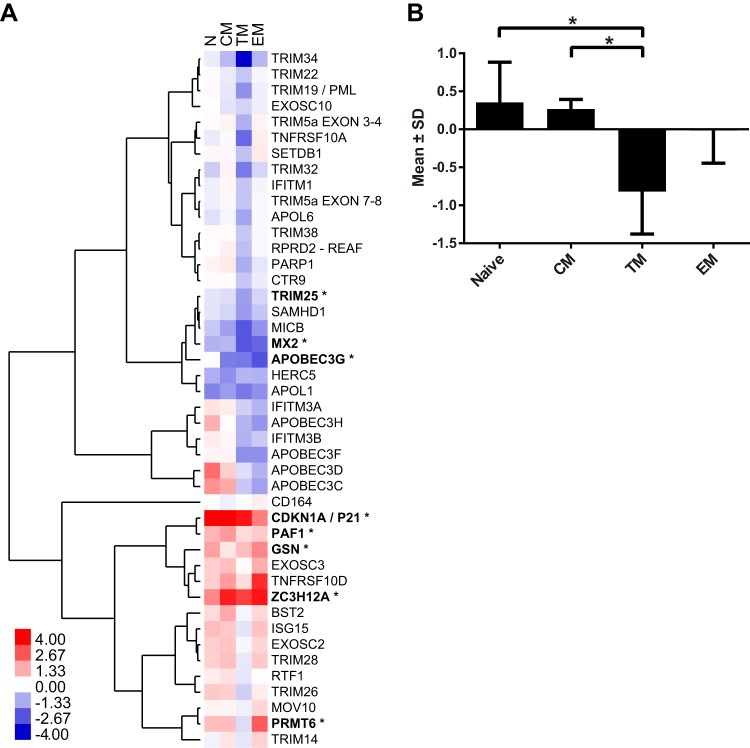

Despite the similarities in the overall pattern of expression of restriction factors between peripheral blood and the jejunum, several differences were apparent. To determine the extent of variation in confirmed and putative restriction factor expression between peripheral blood and jejunum CD4+ T cells, the expression of the target genes in the jejunum relative to peripheral blood was analyzed using the ΔΔCT method (20), normalizing expression to the most stable endogenous control, B2M, and to the respective peripheral blood subset (Fig. 3A). Several genes showed >4-fold-greater differences: APOBEC3D in naive T cells, PRMT6 and TNFRSF10D in effector memory T cells, and ZC3H12A in all three memory CD4+ T cell subsets. Interestingly, eight genes exhibited at least 4-fold mean decreased expression in the CCR5+ transitional memory cells from the jejunum compared to the same subset of CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood. The number of target genes with decreased expression in jejunal CCR5+ transitional memory CD4+ T cells was much larger than the number of genes exhibiting lower expression in central memory (one) or effector memory (two). Using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), the genes that significantly differed in their magnitude of expression between peripheral blood and the jejunum were identified and are noted in Fig. 3A. In addition, genes for which the pattern of expression among the memory subsets differed significantly in the two tissues were identified. There were nine genes with a P value of <0.02: APOBEC3C, APOBEC3D, APOBEC3G, APOBEC3H, APOL6, CDKN1A, PARP1, SAMHD1, and TRIM5.

FIG 3.

Differences in expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in peripheral blood and jejunum CD4+ T cells. (A) Heat map depicting expression in the jejunum relative to peripheral blood and the most stable endogenous control gene, B2M. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed using an uncentered Pearson correlation with complete linkage groups genes with similar expression patterns. The means of four animals are shown (*, P < 0.05 [two-way ANOVA testing tissue differences with an extension of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method]). (B) Mean expression plus the standard deviations (−ΔΔCT) of all restriction factors in the jejunum relative to their respective peripheral blood subset (*, P < 0.05 [paired t test]).

As the overall level of viral restriction mediated by these genes is likely to be cumulative, the overall mean expression of restriction factors from the jejunum relative to the peripheral blood was calculated (Fig. 3B). This value provides a measure of the extent of overall restriction factor expression in each subset for which the only difference between cells was anatomic location. Transitional memory cells from the jejunum had a mean −ΔΔCT value of −0.819, which represents 0.567-fold lower expression. Using a paired t test, this decrease was statistically significantly different from the naive (P = 0.028) and central memory (P = 0.015) subsets, though not for effector CD4+ T cells (P = 0.115).

Acute SIV infection increases expression of restriction factors in CD4+ T cells.

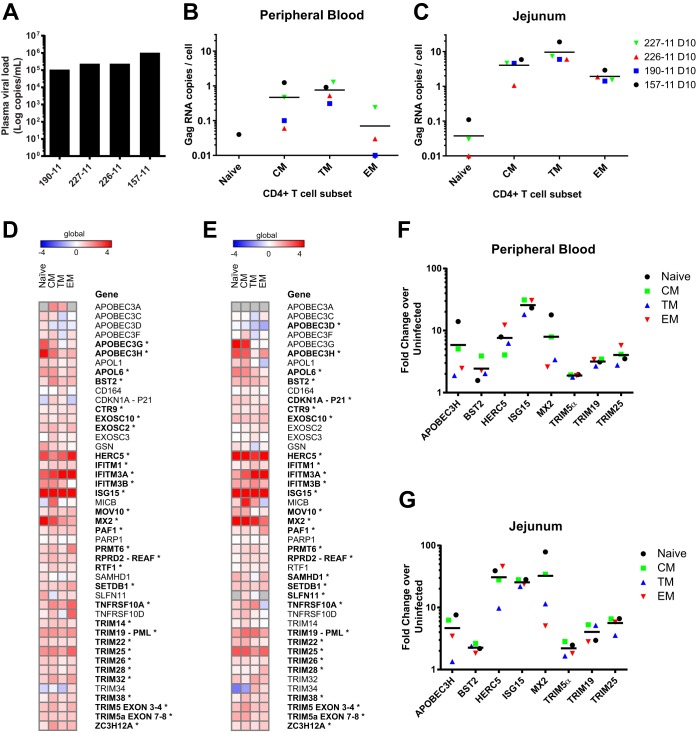

Given the effects of IFN stimulation and T cell activation that we observed on the expression of restriction factors in CD4+ T cells in vitro, we reasoned that the dynamic effects of acute SIV infection, which include induction of a robust type I IFN response (16, 17), would likely have significant effects on the expression of restriction factors in vivo. It is challenging to study the acute phase of immunodeficiency virus infection in humans, especially in the primary target tissue, i.e., gut-associated lymphoid tissue. To investigate potential changes in expression of restriction factors in vivo during acute SIV infection, four rhesus macaques were infected intravenously with SIVMAC239. At 10 days postinfection, the animals were sacrificed, and peripheral blood and jejunum lymphocytes were isolated. Analysis of plasma SIV viral loads demonstrated a geometric mean of 2.8 × 105 copies/ml at 10 days after infection (Fig. 4A). Memory CD4+ T cell subsets were sorted as previously defined, and levels of SIV gag RNA were quantified. In both peripheral blood and the jejunum, the transitional memory CCR5+ CD4+ T cells were the most highly infected memory subset, as expected (Fig. 4B and C). CD4+ T cells from the jejunum in each subset were much more highly infected than from peripheral blood (P = 0.0058, paired t test). The reduced expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors specifically in jejunum transitional memory CD4+ T cells compared to peripheral blood corresponded with increased viral infection of these cells.

FIG 4.

Increased SIV infection in jejunum transitional memory CD4+ T cells and changes in expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors during acute infection. (A) Plasma viral load for each of the four SIV-infected animals at day 10 postinfection. (B and C) The Gag RNA copies per cell equivalent were quantified in sorted CD4+ T cell subsets from peripheral blood (B) and the jejunum (C). (D and E) Heat map of −ΔΔCT expression values depicting memory subset expression in postinfection cells relative to uninfected animals for peripheral blood (D) and the jejunum (E). B2M was used as an endogenous control gene to normalize both uninfected and infected data. Means of four animals per group are shown (*, P < 0.01 [two-way ANOVA with an extension of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method testing differences due to infection]). (F and G) Mean fold change of selected restriction factors from CD4+ T cell subsets postinfection relative to the same subset in uninfected animals for peripheral blood (F) and the jejunum (G).

Strikingly, expression of restriction factors increased in every CD4+ T cell memory subset from both peripheral blood (mean 2.08-fold change increase) and the jejunum (mean 2.14-fold change) 10 days postinfection (Fig. 4D and E) compared to four uninfected animals. On average, 43 of 46 genes increased expression in peripheral blood and 43 of 45 in the jejunum. In particular, peripheral blood cells exhibited a mean increase of >4-fold in APOBEC3H, HERC5, IFITM3A, ISG15, and MX2, whereas jejunum cells increased expression of APOBEC3G, HERC5, IFITIM3A, ISG15, MX2, and TRIM25 >4-fold on average. These genes have been previously reported to be type I ISGs (25, 26), and acute SIV infection has been well documented to induce a strong type I IFN response (17). Using a two-way ANOVA with Benjamini Hochberg correction, approximately two-thirds of the target genes were significantly modulated (P < 0.01) by infection in both peripheral blood and the jejunum, including the known ISGs and nearly all of the TRIM family members. To verify that a global increase in gene expression did not account for upregulation of restriction factors, a panel of 18 endogenous control or lineage genes such as CD3, CD4, CD28, etc., was confirmed to remain quite stable compared to preinfection (mean −ΔΔCT value of −0.04, or a 0.97-fold change [data not shown]). The pattern of restriction factor upregulation was quite similar in peripheral blood compared to the jejunum and naive cells compared to memory cells despite large differences in the levels of infection between the two groups, implicating systemic IFN or cytokine responses as drivers of upregulation.

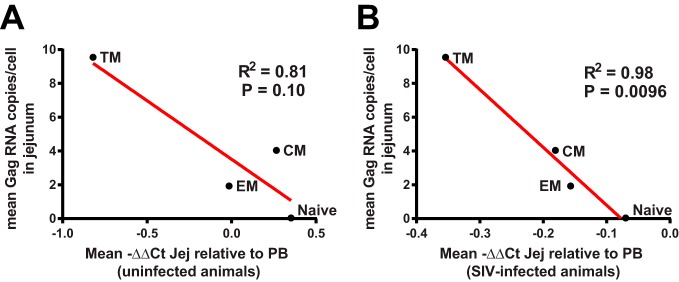

Finally, we also examined whether there was a correlation between the expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in subsets of jejunal CD4+ T cells relative to their counterparts in peripheral blood in uninfected animals and the susceptibility of these various subsets to SIV infection at 10 days postinfection. Although statistical power was limited by the number of samples studied, a trend toward an inverse relationship was observed between expression of restriction factors in jejunum CD4+ T cell memory subsets compared to peripheral blood in uninfected animals and the level of SIV infection in jejunal CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). We did observe a significant relationship between relatively lower levels of expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in CD4+ T cells in the jejunum compared to peripheral blood postinfection and the amount of SIV RNA in jejunal CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5B). Future studies involving larger numbers of samples will be necessary to examine in more detail the relationship between expression of restriction factors in different T cells subsets and their susceptibility to SIV infection.

FIG 5.

Correlation of expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors with the outcome of infection in subsets of CD4+ T cells. The relatively lower levels of expression of confirmed and putative restriction factors in CD4+ T cell subsets in the jejunum compared to peripheral blood (PB) in uninfected animals (ΔΔCT) (A) and in SIV-infected animals (B) correlated with the level of SIV infection in jejunal CD4+ T cell subsets. Data for each CD4+ subset represent the means of four uninfected animals and four infected animals. R2 and P values were calculated using a two-tailed Pearson correlation.

DISCUSSION

We describe here precise expression measurements for 45 confirmed or putative restriction factors in subsets of primary CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood and the jejunum, a critical site for SIV/HIV pathogenesis, under a variety of different conditions. Memory differentiation induced a high dynamic range of expression of restriction factors. For example, we observed a >22-fold average upregulation of APOBEC family genes in the jejunum relative to their expression in naive CD4+ T cells. Paired comparison of the jejunum with peripheral blood CD4+ T cells demonstrated unappreciated differences in expression of restriction factors that could underlie differences in their susceptibility to SIV infection. Specifically, CCR5+ CD4+ T cells from the jejunum showed reduced expression of restriction factors relative to the CCR5+ CD4+ T cells from peripheral blood. In general, memory differentiation had similar effects on the expression of restriction factors in both tissue compartments, increasing the average restriction factor expression. Activation of bulk populations of CD4+ T cells has been shown to increase restriction factor expression (23), and both CD3/CD28 and IFN stimulation dynamically modulated expression of restriction factors. However, despite the overall increased expression of restriction factors in memory CD4+ T cells, these cells are well documented to be more susceptible to SIV and HIV infection (9, 10). This increased susceptibility is likely to reflect factors other than restriction factors that modulate infection such as T cell activation, as well as the ability of SIV to counteract the effects of restriction factors by various mechanisms, including the effects of Vif on APOBEC3G, Nef on tetherin, and Vpx on SAMHD1 (27, 28).

The Fluidigm Biomark qRT-PCR system used in the present study allows for high-throughput, highly quantitative, and precise gene expression measurements with a wide dynamic range of 6 to 8 orders of magnitude, which is significantly wider than microarray-based systems (29). In addition, the specificity of the primer/probe real-time PCR assays permitted discrimination of specific transcript isoforms. TRIM5 is known to be expressed as multiple isoforms in humans. Only the TRIM5α isoform containing the C-terminal SPRY domain is capable of restricting HIV/SIV, while other isoforms can act in a dominant negative fashion to inactivate the α isoform (22). Here, we found that the α isoform is present at about 50% of the abundance of total TRIM5 in primary CD4+ T cells from both the jejunum and peripheral blood. However, various forms of stimulation, including memory differentiation, CD3/CD28, IFN, and SIV infection, did not appreciably alter the relative abundance of the α isoform to that of total TRIM5 despite altering the total level of expression.

Prior studies have demonstrated that mRNA levels generally correlate well with protein expression, especially for immune response genes (such as restriction factors) that are dynamically modulated following cell stimulation (30–32). While efforts to address this issue for macaque restriction factors are complicated by the paucity of validated reagents, we did observe a significant correlation between surface CCR5 and CD28 protein expression with their respective mRNA levels in subsets of macaque CD4+ T cells (data not shown). However, it is important to bear in mind that a number of factors, including the potential for posttranslational regulation (33), can modulate expression of restriction factors, and future studies will be necessary to correlate the protein expression of individual restriction factors with the susceptibility to SIV infection in different CD4+ T cell subsets. Since we examined expression of restriction factors in defined phenotypic subsets of CD4+ T cells, the observed changes in the relative expression of restriction factors after SIV infection are likely to reflect true upregulation of restriction factors in specific populations of CD4+ T cells rather than the confounding effects of redistribution of CD4+ T cells among different compartments during acute infection.

This study utilized the advantages of the rhesus macaque/SIV model to understand the expression changes of confirmed and putative restriction factors in primary cells and cells from tissues that are difficult to study in humans, especially during acute infection. In particular, mucosal tissues are the primary site of transmission and the major site for replication and CD4+ T cell depletion in HIV/SIV infection (11–14). SIV infection of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood is relatively infrequent (0.1 to 1%) during acute SIV infection, whereas up to 60% of mucosal CD4+ T cells can be infected during this time (9, 13). Here, we observed increased levels of infection in each CD4+ T cell subset in the jejunum compared to peripheral blood, verifying mucosal CD4+ T cells as particularly susceptible targets. Although the precise mechanisms remain unclear, multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain this increased susceptibility to SIV/HIV infection, including a greater proportion of CCR5-expressing cells, fewer naive cells, more activated cells with higher levels of transcription, the closer proximity of target cells facilitating cell-cell spread, and additional factors, such as increased α4β7 expression facilitating the binding of virions (34). We show here that in the CCR5-expressing transitional memory subset with the same phenotype from peripheral blood and the jejunum, cells from the jejunum expressed relatively lower levels of restriction factor genes, potentially contributing to their increased levels of infection.

Previous studies have measured the expression of a subset of the restriction factors included in this study under certain conditions. For example, PBMCs from HIV-naive subjects stimulated with PHA induced upregulation of genes such as ISG15, APOBEC3G, and TRIM5 (23). IFN-α treatment of HIV/HCV-coinfected patients resulted in the upregulation of a subset of restriction factor genes such as ISG15 and TRIM19 (PML), a finding in agreement with our results (35, 36). However, these studies measured restriction factor expression in either total PBMCs or total CD4+ T cells. As shown in the present study, restriction factor expression can vary significantly among different memory subsets. Therefore, analysis of the expression of specific restriction factors in specific populations of target cells may be more informative than analysis in bulk populations of CD4+ T cells.

We demonstrated dynamic modulation of restriction factor expression in CD4+ T cells due to differentiation, activation, IFN stimulation, and SIV infection. All forms of stimulation induced different patterns of expression of restriction factors. For example, memory differentiation increased expression of all APOBEC family members, whereas anti-CD3/CD28, IFN, and SIV infection increased the expression of only selected APOBEC genes. Differential effects of stimulation suggest different mechanisms of regulation. Acute SIV infection is known to induce robust upregulation of interferon expression (16, 17). However, in vitro IFN stimulation induced the expression of only 32% of the measured target genes, whereas acute SIV infection increased the expression of nearly every gene, suggesting that type I IFN alone is insufficient to account for the full range of expression modulation during infection. Previous studies have found a wide range of cytokine/chemokine production during acute SIV/HIV infection (37, 38), and future studies will be required to determine the specific contributions of these signals to regulation of expression of restriction factors.

Recent research shows that innate immune responses may be suppressed in the first days postinfection, allowing viral replication to progress (39). We showed here that nearly all of the analyzed confirmed and putative restriction factors increased in expression in both peripheral blood and jejunum CD4+ T cells at 10 days postinfection, with ISGs exhibiting the greatest extent of upregulation. Although these restriction factors may play a role in inhibiting SIV replication, this dramatic upregulation does not occur until after systemic infection has been established. The kinetics of restriction factor expression changes during the earliest phases of acute pathogenic infection are still unknown, including whether cells at the earliest sites of viral replication display gene expression changes before peripheral cells. In addition, it is still unknown whether differences in restriction factor expression may underlie differences in susceptibility to infection at the organismal level.

Taken together, these data highlight the dynamic regulation of expression of restriction factors, which can be modulated by multiple factors, including cell differentiation, anatomic compartment, T cell activation, and acute SIV infection. Although other factors clearly play a role, modulation of expression of restriction factors is likely to play a significant role in the wide range of differential susceptibility of distinct CD4+ T cell subsets to SIV infection. Future studies will be necessary to better to define the roles of individual restriction factors to the susceptibility of primary CD4+ T cells to SIV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The eight Indian-origin rhesus macaque monkeys (Macaca mulatta) described in this study were housed at the New England Primate Research Center (NEPRC) in accordance with the regulations of the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and the standards of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All protocols and procedures were approved by the relevant Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Care met the guidance of the Animal Welfare Regulations, OLAW reporting, and the standards set forth in The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (40). Euthanasia took place at 10 days postinfection using protocols consistent with the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) guidelines.

Infection of four animals was performed intravenously with 500 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of SIVmac239 (generously provided by Francois Villinger, Emory University). The use of an intravenous route of inoculation ensured a reliable and synchronous infection with a well-studied disease course. Euthanasia took place at 10 days postinfection using protocols consistent with the AVMA guidelines.

Lymphocyte isolation.

Peripheral blood samples were collected from unvaccinated healthy rhesus macaques for purification of CD4+ T cells. Blood was collected in EDTA Vacutainer tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and PBMCs were separated by density gradient centrifugation (lymphocyte separation medium; MP Biomedicals, Inc., Solon, OH). Jejunum tissue was isolated at time of euthanasia, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, separated into small pieces with a scalpel, incubated with 5 mM EDTA for 30 min, washed, and incubated with 15 U of type II collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich)/ml, followed by mechanical disruption with an 18-gauge feeding needle and filtration through 70-μm-pore size cell strainers (BD Biosciences). Lymphocytes were then enriched by bilayer (35%/60%) isotonic Percoll density gradient centrifugation (1,000 × g, 20 min), and the interface containing the lymphocytes was collected (41).

Antibodies and cell sorting.

To purify naive and memory phenotypes, PBMCs were stained with CD3 (SP34)-Pacific Blue, CD4 (L200)-FITC; CD8 (RPA-T8)-Alexa 700, CD28 (28.2)-ECD (Beckman Coulter), CD95 (DX2)-APC, CCR5 (3A9)-PE, and CCR7 (2D12)-PE-Cy7. Antibodies were obtained from BD Pharmingen unless specified otherwise. PBMCs were initially labeled with Live/Dead viability stain (Life Technologies) and washed, followed by incubation with CCR7 antibody for 15 min at 37°C, then incubation with all other antibodies was done for 20 min at room temperature, and finally, the PBMCs were washed prior to sorting. Cell sorting was performed using a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Sorts were >99% pure for all populations.

In vitro cell stimulation.

CD4+ T cell enrichment prior to stimulation with αCD3/αCD28 or IFN was performed using the CD4+ T cell nonhuman primate isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). As verified by flow cytometry, purity was >95%. For anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, αCD3/αCD28 beads were generated by coupling αCD3 (FN-18) and αCD28 (L293) antibodies with Dynabeads M-450 tosyl-activated (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 1:1 ratio according to the manufacturer's instructions. Beads were added to cells in a 3:1 ratio for stimulation. For IFN stimulation, recombinant human IFN-αA/D (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to cultures of freshly isolated and enriched CD4+ T cells at a concentration of 1,000 U/ml. In both stimulation experiments, paired samples of unstimulated cells were used as controls.

Gene expression analysis.

Real-time PCR assays specific for the indicated rhesus macaque genes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (ABI) (Table 1). When not available, macaque-specific custom assays with FAM-MGB probes were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (ABI). The sequences for the custom assays were as follows: APOBEC3D, F-TCCCTGCACTGCAAGCTAAA, R-TGTGTGTGGATACATTGCCTTCA, and P-AGATTCTCAGAAACCC; APOL1, F-CTGGAGGCATCTTGCTTGTG, R-TCTTGCAAGTGCTTTGACTCGTA, and P-ATGTGGTCAGCCTTGT; APOL6 F-AGGCAGAGGAAGAAAGTGAAGCT, R-TCGTCTTCACACAGAGGAACATCT, and P-TTGGTTTGGAAAGGGATGAG; HERC5, F-GGACATACAGATTATGATTGGAAAACA, R-TCACTATGGTGGGATGTGAACTG, and P-TTGAAAAGAATGCACGTTATG; IFITM3A, F-GGCCAGCCTCCCAACTATG, R-GGGCGCCCCCATCAT, and P-AAGAGCACGATGTGGC; IFITM3B, F-AAACCGTCTTCCCTCCTGTCA, R-GCTACCTCATGCTCTTCCTTGAG, and P-CCCCCCAGCTATGAG; SLFN14, F-GAGGGTCTGCAACGACATTTG, R-GCTTCTTACAGAGGGATTCTGGTT, and P-TTCCAGTGACACAGCAA; TRIM14, F-CAGCCAGGAGCCTGATCCT, R-CCGCTGCATCTCCTGCTT, and P-AGAGGCTTCAGGCATACA; and TRIM32, F-GGCCTCAATCTGGAGAATCG, R-AACCAATGGAAAAGCCACCTT, and P-CAGAATGAGCACCACCTG. The primer sequences for the SIV gag custom assay were as follows: F-GUCUGCGUCAUCUGGUGCAUUC, R-CAAAACAGAUAGUGCAGAGACACCUAGUG, and P-CGCAGAAGAGAAAGUGAAACACACUGAGGAAG. All assays were confirmed to exhibit linear amplification in an eight-point, 3-fold dilution series of rhesus PBMC cDNA.

Sorted cells were immediately frozen at −80°C in RNA extraction buffer. RNA extraction was performed on thawed samples using a Qiagen RNeasy Plus Micro kit, RNA purity was confirmed using an Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Bioanalyzer kit, and conversion to cDNA was performed using ABI high-capacity RT with random hexamer primers. cDNA samples were diluted to 200 cell equivalents, linearly preamplified with gene-specific primers with an ABI Preamp master mix kit and pooled TaqMan assays, and analyzed on a Fluidigm BioMark microfluidic real-time PCR system using 96.96 dynamic arrays. This system allows for the simultaneous measurement of up to 96 assays in 96 different cDNA samples. Initial calculations of cycle thresholds (CT) were performed using the Fluidigm BioMark software version 4.1.3, and further analysis was carried out using GenEx software version 6 (MultiD Analyses [http://www.multid.se]). Calculated ΔCT values, which were normalized to expression of a stable endogenous control gene, for CD4+ T cell subsets from uninfected and SIV-infected animals are presented in Dataset S1 in the supplemental material.

For SIV RT-PCR quantification, an eight-point 5-fold standard curve was constructed of in vitro-transcribed SIVmac239 gag RNA and used to interpolate the number of gag RNA copies in each cell sample. Copies per cell were calculated based on the number of cells in the reaction.

Plasma viral loads.

Plasma viral RNA levels were quantitated using real-time PCR, and SIV RNA copy number was determined by comparison to an external standard curve (73, 74).

Statistical analysis.

Statistics and graphing were performed using Prism (v6.05 for Windows; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) or R (75). Naive and memory CD4+ T cell restriction factor expression was compared using repeated-measures ANOVA with an extension of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (76). PCA was performed using R and the function hclust (75) with resulting axis coordinates and loading factors visualized in GraphPad Prism. Peripheral blood and jejunum memory subsets were compared using two-way ANOVA with an extension of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method (77, 78). Aggregate peripheral blood and jejunum expression differences were assessed with a paired Student t test. Pre- and postinfection differences were assessed using a two-way ANOVA with an extension of the Benjamini-Hochberg correction.

For all multiple comparison corrections, the R function p.adjust(), written by Gordon Smyth and implemented in the R package limma (77), was used. It is an extension of the original Benjamini-Hochberg methods, as updated by Storey (78).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Francois Villinger (Emory University) for providing the SIVmac239 virus stock; Arnaud Colantonio for study coordination, Jackie Gillis and Michelle Connole for flow cytometry support, and Thomas Vanderford, Benton Lawson, and the Emory CFAR Virology Core for plasma viral load determinations. We thank Jeffrey Lifson (NCI-Frederick) for providing advice on the SIV PCR primers. We also thank Amber Hoggatt and other members of the NEPRC Division of Veterinary Resources for their expert animal care, and we thank Elizabeth Curran and other members of the NEPRC Pathology Division for their assistance.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants P51 OD011103 and P51 OD011132 and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409), as well as funding from the Mucosal Immunology Group (http://public.hivmucosalgroup.org), which is supported by a supplement to the HVTN Laboratory Program (UM1AI068618).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02189-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Malim MH. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat Med 9:1404–1407. doi: 10.1038/nm945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stremlau M, Perron M, Lee M, Li Y, Song B, Javanbakht H, Diaz-Griffero F, Anderson DJ, Sundquist WI, Sodroski J. 2006. Specific recognition and accelerated uncoating of retroviral capsids by the TRIM5α restriction factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:5514–5519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neil SJ, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. 2008. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature 451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Damme N, Goff D, Katsura C, Jorgenson RL, Mitchell R, Johnson MC, Stephens EB, Guatelli J. 2008. The interferon-induced protein BST-2 restricts HIV-1 release and is downregulated from the cell surface by the viral Vpu protein. Cell Host Microbe 3:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Segeral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. 2011. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Oliveira NM, Cheney KM, Pade C, Dreja H, Bergin AM, Borgdorff V, Beach DH, Bishop CL, Dittmar MT, McKnight A. 2011. A whole-genome screen for HIV restriction factors. Retrovirology 8:94. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaren PJ, Gawanbacht A, Pyndiah N, Krapp C, Hotter D, Kluge SF, Gotz N, Heilmann J, Mack K, Sauter D, Thompson D, Perreaud J, Rausell A, Munoz M, Ciuffi A, Kirchhoff F, Telenti A. 2015. Identification of potential HIV restriction factors by combining evolutionary genomic signatures with functional analyses. Retrovirology 12:41. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripathi SK, Lahesmaa R. 2014. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of T-helper lineage specification. Immunol Rev 261:62–83. doi: 10.1111/imr.12204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenchley JM, Hill BJ, Ambrozak DR, Price DA, Guenaga FJ, Casazza JP, Kuruppu J, Yazdani J, Migueles SA, Connors M, Roederer M, Douek DC, Koup RA. 2004. T-cell subsets that harbor human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vivo: implications for HIV pathogenesis. J Virol 78:1160–1168. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1160-1168.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun TW, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Siliciano RF. 1997. Differential susceptibility of naive and memory CD4+ T cells to the cytopathic effects of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strain LAI. J Virol 71:4436–4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veazey RS, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Shvetz D, Pauley D, Knight HL, Rosenzweig M, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC, Lackner AA. 1998. The gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4 T lymphocyte depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 280:427–431. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, Ma ZM, Rourke T, Wang Y, Reilly C, Carlis J, Miller CJ, Haase AT. 2005. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature 434:1148–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattapallil JJ, Douek DC, Hill B, Nishimura Y, Martin M, Roederer M. 2005. Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature03501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lackner AA, Mohan M, Veazey RS. 2009. The gastrointestinal tract and AIDS pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 136:1965–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veazey RS, Rosenzweig M, Shvetz DE, Pauley DR, DeMaria M, Chalifoux LV, Johnson RP, Lackner AA. 1997. Characterization of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) of normal rhesus macaques. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 82:230–242. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.4318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahmberg AR, Neidermyer WJ Jr, Breed MW, Alvarez X, Midkiff CC, Piatak M Jr, Lifson JD, Evans DT. 2013. Tetherin upregulation in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Virol 87:13917–13921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01757-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandler NG, Bosinger SE, Estes JD, Zhu RT, Tharp GK, Boritz E, Levin D, Wijeyesinghe S, Makamdop KN, del Prete GQ, Hill BJ, Timmer JK, Reiss E, Yarden G, Darko S, Contijoch E, Todd JP, Silvestri G, Nason M, Norgren RB Jr, Keele BF, Rao S, Langer JA, Lifson JD, Schreiber G, Douek DC. 2014. Type I interferon responses in rhesus macaques prevent SIV infection and slow disease progression. Nature 511:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature13554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitcher CJ, Hagen SI, Walker JM, Lum R, Mitchell BL, Maino VC, Axthelm MK, Picker LJ. 2002. Development and homeostasis of T cell memory in rhesus macaque. J Immunol 168:29–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Picker LJ, Reed-Inderbitzin EF, Hagen SI, Edgar JB, Hansen SG, Legasse A, Planer S, Piatak M Jr, Lifson JD, Maino VC, Axthelm MK, Villinger F. 2006. IL-15 induces CD4 effector memory T cell production and tissue emigration in nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 116:1514–1524. doi: 10.1172/JCI27564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen CL, Jensen JL, Orntoft TF. 2004. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res 64:5245–5250. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battivelli E, Migraine J, Lecossier D, Matsuoka S, Perez-Bercoff D, Saragosti S, Clavel F, Hance AJ. 2011. Modulation of TRIM5α activity in human cells by alternatively spliced TRIM5 isoforms. J Virol 85:7828–7835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00648-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raposo RA, Abdel-Mohsen M, Bilska M, Montefiori DC, Nixon DF, Pillai SK. 2013. Effects of cellular activation on anti-HIV-1 restriction factor expression profile in primary cells. J Virol 87:11924–11929. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02128-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parlato S, Romagnoli G, Spadaro F, Canini I, Sirabella P, Borghi P, Ramoni C, Filesi I, Biocca S, Gabriele L, Belardelli F. 2010. LOX-1 as a natural IFN-alpha-mediated signal for apoptotic cell uptake and antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Blood 115:1554–1563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henig N, Avidan N, Mandel I, Staun-Ram E, Ginzburg E, Paperna T, Pinter RY, Miller A. 2013. Interferon-beta induces distinct gene expression response patterns in human monocytes versus T cells. PLoS One 8:e62366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanda C, Weitzel P, Tsukahara T, Schaley J, Edenberg HJ, Stephens MA, McClintick JN, Blatt LM, Li L, Brodsky L, Taylor MW. 2006. Differential gene induction by type I and type II interferons and their combination. J Interferon Cytokine Res 26:462–472. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris RS, Hultquist JF, Evans DT. 2012. The restriction factors of human immunodeficiency virus. J Biol Chem 287:40875–40883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.416925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahm N, Telenti A. 2012. The role of tripartite motif family members in mediating susceptibility to HIV-1 infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 7:180–186. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32835048e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Barbacioru C, Hyland F, Xiao W, Hunkapiller KL, Blake J, Chan F, Gonzalez C, Zhang L, Samaha RR. 2006. Large-scale real-time PCR validation on gene expression measurements from two commercial long-oligonucleotide microarrays. BMC Genomics 7:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jovanovic M, Rooney MS, Mertins P, Przybylski D, Chevrier N, Satija R, Rodriguez EH, Fields AP, Schwartz S, Raychowdhury R, Mumbach MR, Eisenhaure T, Rabani M, Gennert D, Lu D, Delorey T, Weissman JS, Carr SA, Hacohen N, Regev A. 2015. Immunogenetics: dynamic profiling of the protein life cycle in response to pathogens. Science 347:1259038. doi: 10.1126/science.1259038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwanhausser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. 2011. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, Wu G, Chen L, Zhang W. 2016. Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic datasets reveals information on protein expressivity and factors affecting translational efficiency. Methods Mol Biol 1375:123–136. doi: 10.1007/7651_2015_242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M. 2013. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep 3:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lackner AA, Lederman MM, Rodriguez B. 2012. HIV pathogenesis: the host. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a007005. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdel-Mohsen M, Deng X, Liegler T, Guatelli JC, Salama MS, Ghanem Hel D, Rauch A, Ledergerber B, Deeks SG, Gunthard HF, Wong JK, Pillai SK. 2014. Effects of alpha interferon treatment on intrinsic anti-HIV-1 immunity in vivo. J Virol 88:763–767. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02687-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pillai SK, Abdel-Mohsen M, Guatelli J, Skasko M, Monto A, Fujimoto K, Yukl S, Greene WC, Kovari H, Rauch A, Fellay J, Battegay M, Hirschel B, Witteck A, Bernasconi E, Ledergerber B, Gunthard HF, Wong JK; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. 2012. Role of retroviral restriction factors in the interferon-alpha-mediated suppression of HIV-1 in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:3035–3040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111573109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stacey AR, Norris PJ, Qin L, Haygreen EA, Taylor E, Heitman J, Lebedeva M, DeCamp A, Li D, Grove D, Self SG, Borrow P. 2009. Induction of a striking systemic cytokine cascade prior to peak viremia in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, in contrast to more modest and delayed responses in acute hepatitis B and C virus infections. J Virol 83:3719–3733. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01844-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu H, Wang X, Morici LA, Pahar B, Veazey RS. 2011. Early divergent host responses in SHIVsf162P3 and SIVmac251-infected macaques correlate with control of viremia. PLoS One 6:e17965. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barouch DH, Ghneim K, Bosche WJ, Li Y, Berkemeier B, Hull M, Bhattacharyya S, Cameron M, Liu J, Smith K, Borducchi E, Cabral C, Peter L, Brinkman A, Shetty M, Li H, Gittens C, Baker C, Wagner W, Lewis MG, Colantonio A, Kang HJ, Li W, Lifson JD, Piatak M Jr, Sekaly RP. 2016. Rapid inflammasome activation following mucosal SIV infection of rhesus monkeys. Cell 165:656–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Research Council. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th ed National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdel-Motal UM, Gillis J, Manson K, Wyand M, Montefiori D, Stefano-Cole K, Montelaro RC, Altman JD, Johnson RP. 2005. Kinetics of expansion of SIV Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes following challenge of vaccinated macaques. Virology 333:226–238. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desimmie BA, Delviks-Frankenberrry KA, Burdick RC, Qi D, Izumi T, Pathak VK. 2014. Multiple APOBEC3 restriction factors for HIV-1 and one Vif to rule them all. J Mol Biol 426:1220–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitt K, Guo K, Algaier M, Ruiz A, Cheng F, Qiu J, Wissing S, Santiago ML, Stephens EB. 2011. Differential virus restriction patterns of rhesus macaque and human APOBEC3A: implications for lentivirus evolution. Virology 419:24–42. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hultquist JF, Lengyel JA, Refsland EW, LaRue RS, Lackey L, Brown WL, Harris RS. 2011. Human and rhesus APOBEC3D, APOBEC3F, APOBEC3G, and APOBEC3H demonstrate a conserved capacity to restrict Vif-deficient HIV-1. J Virol 85:11220–11234. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05238-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH. 2002. Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein. Nature 418:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor HE, Khatua AK, Popik W. 2014. The innate immune factor apolipoprotein L1 restricts HIV-1 infection. J Virol 88:592–603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02828-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, Rice CM. 2011. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature 472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith EE, Malik HS. 2009. The apolipoprotein L family of programmed cell death and immunity genes rapidly evolved in primates at discrete sites of host-pathogen interactions. Genome Res 19:850–858. doi: 10.1101/gr.085647.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen H, Li C, Huang J, Cung T, Seiss K, Beamon J, Carrington MF, Porter LC, Burke PS, Yang Y, Ryan BJ, Liu R, Weiss RH, Pereyra F, Cress WD, Brass AL, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Yu XG, Lichterfeld M. 2011. CD4+ T cells from elite controllers resist HIV-1 infection by selective upregulation of p21. J Clin Invest 121:1549–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI44539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergamaschi A, David A, Le Rouzic E, Nisole S, Barre-Sinoussi F, Pancino G. 2009. The CDK inhibitor p21Cip1/WAF1 is induced by FcγR activation and restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and related primate lentiviruses in human macrophages. J Virol 83:12253–12265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01395-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia-Exposito L, Ziglio S, Barroso-Gonzalez J, de Armas-Rillo L, Valera MS, Zipeto D, Machado JD, Valenzuela-Fernandez A. 2013. Gelsolin activity controls efficient early HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology 10:39. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woods MW, Kelly JN, Hattlmann CJ, Tong JG, Xu LS, Coleman MD, Quest GR, Smiley JR, Barr SD. 2011. Human HERC5 restricts an early stage of HIV-1 assembly by a mechanism correlating with the ISGylation of Gag. Retrovirology 8:95. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu J, Pan Q, Rong L, He W, Liu SL, Liang C. 2011. The IFITM proteins inhibit HIV-1 infection. J Virol 85:2126–2137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01531-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burdick R, Smith JL, Chaipan C, Friew Y, Chen J, Venkatachari NJ, Delviks-Frankenberry KA, Hu WS, Pathak VK. 2010. P body-associated protein Mov10 inhibits HIV-1 replication at multiple stages. J Virol 84:10241–10253. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00585-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X, Han Y, Dang Y, Fu W, Zhou T, Ptak RG, Zheng YH. 2010. Moloney leukemia virus 10 (MOV10) protein inhibits retrovirus replication. J Biol Chem 285:14346–14355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goujon C, Moncorge O, Bauby H, Doyle T, Ward CC, Schaller T, Hue S, Barclay WS, Schulz R, Malim MH. 2013. Human MX2 is an interferon-induced post-entry inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature 502:559–562. doi: 10.1038/nature12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kane M, Yadav SS, Bitzegeio J, Kutluay SB, Zang T, Wilson SJ, Schoggins JW, Rice CM, Yamashita M, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD. 2013. MX2 is an interferon-induced inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature 502:563–566. doi: 10.1038/nature12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bueno MT, Reyes D, Valdes L, Saheba A, Urias E, Mendoza C, Fregoso OI, Llano M. 2013. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 promotes transcriptional repression of integrated retroviruses. J Virol 87:2496–2507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01668-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boulanger MC, Liang C, Russell RS, Lin R, Bedford MT, Wainberg MA, Richard S. 2005. Methylation of Tat by PRMT6 regulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene expression. J Virol 79:124–131. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.124-131.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singhroy DN, Mesplede T, Sabbah A, Quashie PK, Falgueyret JP, Wainberg MA. 2013. Automethylation of protein arginine methyltransferase 6 (PRMT6) regulates its stability and its anti-HIV-1 activity. Retrovirology 10:73. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marno KM, Ogunkolade BW, Pade C, Oliveira NM, O'Sullivan E, McKnight A. 2014. Novel restriction factor RNA-associated early-stage anti-viral factor (REAF) inhibits human and simian immunodeficiency viruses. Retrovirology 11:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Descours B, Cribier A, Chable-Bessia C, Ayinde D, Rice G, Crow Y, Yatim A, Schwartz O, Laguette N, Benkirane M. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 reverse transcription in quiescent CD4+ T cells. Retrovirology 9:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li M, Kao E, Gao X, Sandig H, Limmer K, Pavon-Eternod M, Jones TE, Landry S, Pan T, Weitzman MD, David M. 2012. Codon-usage-based inhibition of HIV protein synthesis by human Schlafen 11. Nature 491:125–128. doi: 10.1038/nature11433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turelli P, Doucas V, Craig E, Mangeat B, Klages N, Evans R, Kalpana G, Trono D. 2001. Cytoplasmic recruitment of INI1 and PML on incoming HIV preintegration complexes: interference with early steps of viral replication. Mol Cell 7:1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singh R, Gaiha G, Werner L, McKim K, Mlisana K, Luban J, Walker BD, Karim SS, Brass AL, Ndung'u T, Team CAIS. 2011. Association of TRIM22 with the type 1 interferon response and viral control during primary HIV-1 infection. J Virol 85:208–216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01810-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kajaste-Rudnitski A, Marelli SS, Pultrone C, Pertel T, Uchil PD, Mechti N, Mothes W, Poli G, Luban J, Vicenzi E. 2011. TRIM22 inhibits HIV-1 transcription independently of its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, Tat, and NF-κB-responsive long terminal repeat elements. J Virol 85:5183–5196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02302-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uchil PD, Quinlan BD, Chan WT, Luna JM, Mothes W. 2008. TRIM E3 ligases interfere with early and late stages of the retroviral life cycle. PLoS Pathog 4:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Allouch A, Di Primio C, Alpi E, Lusic M, Arosio D, Giacca M, Cereseto A. 2011. The TRIM family protein KAP1 inhibits HIV-1 integration. Cell Host Microbe 9:484–495. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fridell RA, Harding LS, Bogerd HP, Cullen BR. 1995. Identification of a novel human zinc finger protein that specifically interacts with the activation domain of lentiviral Tat proteins. Virology 209:347–357. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang F, Hatziioannou T, Perez-Caballero D, Derse D, Bieniasz PD. 2006. Antiretroviral potential of human tripartite motif-5 and related proteins. Virology 353:396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stremlau M, Owens CM, Perron MJ, Kiessling M, Autissier P, Sodroski J. 2004. The cytoplasmic body component TRIM5α restricts HIV-1 infection in Old World monkeys. Nature 427:848–853. doi: 10.1038/nature02343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu S, Qiu C, Miao R, Zhou J, Lee A, Liu B, Lester SN, Fu W, Zhu L, Zhang L, Xu J, Fan D, Li K, Fu M, Wang T. 2013. MCPIP1 restricts HIV infection and is rapidly degraded in activated CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:19083–19088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316208110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hofmann-Lehmann R, Swenerton RK, Liska V, Leutenegger CM, Lutz H, McClure HM, Ruprecht RM. 2000. Sensitive and robust one-tube real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction to quantify SIV RNA load: comparison of one- versus two-enzyme systems. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 16:1247–1257. doi: 10.1089/08892220050117014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amara RR, Villinger F, Altman JD, Lydy SL, O'Neil SP, Staprans SI, Montefiori DC, Xu Y, Herndon JG, Wyatt LS, Candido MA, Kozyr NL, Earl PL, Smith JM, Ma HL, Grimm BD, Hulsey ML, Miller J, McClure HM, McNicholl JM, Moss B, Robinson HL. 2001. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science 292:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1058915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.R Core Team. 2014. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. 2015. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Storey JD. 2002. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 64:479–498. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Furtak V, Mulky A, Rawlings SA, Kozhaya L, Lee K, Kewalramani VN, Unutmaz D. 2010. Perturbation of the P-body component Mov10 inhibits HIV-1 infectivity. PLoS One 5:e9081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tissot C, Mechti N. 1995. Molecular cloning of a new interferon-induced factor that represses human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat expression. J Biol Chem 270:14891–14898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.