Abstract

Purpose

The multiple mechanisms used by solid tumors to suppress tumor-specific immune responses are a major barrier to the success of adoptively-transferred tumor-specific T-cells. Since viruses induce potent innate and adaptive immune responses, we hypothesized that the immunogenicity of viruses could be harnessed for the treatment of solid tumors if virus-specific T-cells (VSTs) were modified with tumor-specific chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). We tested this hypothesis using VZV-specific T-cells (VZVSTs) expressing a CAR for GD2, a disialoganglioside expressed on neuroblastoma and certain other tumors, since the live-attenuated VZV vaccine could be used for in vivo stimulation.

Experimental Design

We generated GMP-compliant, GD2.CAR-modified VZVSTs from healthy donors and cancer patients by stimulation with overlapping peptide libraries spanning selected VZV antigens, then tested their ability to recognize and kill GD2- and VZV antigen-expressing target cells.

RESULTS

Our choice of VZV antigens was validated by the observation that T-cells specific for these antigens expanded in vivo after VZV vaccination. VZVSTs secreted cytokines in response to VZV antigens, killed VZV infected target cells and limited infectious virus spread in autologous fibroblasts. However, while GD2.CAR-modified VZVSTs killed neuroblastoma cell lines on their first encounter, they failed to control tumor cells in subsequent cocultures. Despite this CAR-specific dysfunction, CAR-VZVSTs retained functional specificity for VZV antigens via their TCRs and GD2.CAR function was partially rescued by stimulation through the TCR or exposure to dendritic cell supernatants.

CONCLUSION

Vaccination via the TCR may provide a means to reactivate CAR-T-cells rendered dysfunctional by the tumor microenvironment. (NCT01953900).

Keywords: Chimeric antigen receptor, VZV, virus-specific T-cell, immunotherapy, vaccination

Introduction

T-cells of any native specificity can be made tumor-specific by modification with tumor-specific CARs. CD19-CARs incorporating costimulatory endodomains have had great success for the treatment of B-cell malignancies [1]. However, CAR-T-cells directed to solid tumors have been less effective, [2, 3] due in part to their highly immunosuppressive microenvironment and to their inhibitory phenotype that contrasts with the costimulatory phenotype of B-cells that provides professional costimulation to CD19-directed CAR T-cells.

In most clinical studies, CARs are introduced into polyclonally-activated T-cells whose native antigen specificities are unknown. Hence in vivo CAR-T-cell proliferation is dependent on CAR ligation as well as lymphodepletion of the patient to provide homeostatic cytokines. Our group evaluated a different strategy to enhance CAR-T-cell persistence: To test the hypothesis that endogenous Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected B-cells would provide in vivo stimulation of CAR-T-cells via the native TCR, we infused EBV-specific T-cells (EBVSTs) modified with a first generation GD2-CAR into patients with neuroblastoma, [4]. Indeed GD2.CAR-EBVSTs circulated with higher frequency than similarly modified CD3-activated T-cells (ATCs) in the first six weeks after infusion. Five of 11 children with measurable disease had tumor responses, including 3 complete remissions (CRs), illustrating the therapeutic potential of CAR-modified virus-specific T-cells (VSTs) for solid tumors [5, 6]. However, even in responders, GD2.CAR-EBVST expansion could not be detected in peripheral blood, as measured by PCR for the transgene, and patients with bulky disease did not attain CRs. The lack of proliferation of CAR-EBVSTs in patients with neuroblastoma contrasted with the exponential proliferation of EBVSTs after infusion into hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) recipients. Important differences between these patient groups include the lymphopenic state and high EBV load of many HSCT recipients.[7–9] By contrast neuroblastoma patients were not lymphopenic and did not have elevated EBV loads.

Routine vaccination provides a minimally toxic means to break the homeostatic control of memory T-cells and produce antigen-specific T-cell expansion in vivo, even under normal homeostatic conditions. Since there is no commercially available vaccine for EBV, we considered the use of the VZV, another human herpesvirus for which successful vaccines have been licensed for widespread use. VARIVAX is a live attenuated VZV vaccine, that has been used safely in millions of children [10] and ZOSTAVAX, a 14-fold higher dose of the same strain has been used as a booster vaccine in VZV seropositive adults.[11, 12] These safe vaccines should provide a potent strategy to induce in vivo activation and proliferation of adoptively transferred VZVSTs that are genetically modified with a tumor-specific CAR. T cells specific for a number of VZV protein antigens have been identified, most notably for the immediate early (IE) proteins 62 and 63 and the glycoprotein gE [13–23].

We previously demonstrated that memory VZVSTs could be reactivated and expanded using VZV lysate-pulsed dendritic cells (DCs) and modified to express first and second generation CARs for GD2 and CD19 [24]. We have now developed an improved, targeted, GMP-compliant approach by activating VZVSTs with overlapping peptide libraries spanning immediate early (IE) and abundant virion proteins of VZV. Here, we show that the frequency of T-cells specific for five VZV proteins (gE, IE61, IE62, IE63 and ORF10) increase in response to both primary and booster vaccination, and that these cells can be genetically modified with a third generation GD2.CAR and expanded to clinically relevant numbers in vitro. CAR-modified VZVSTs recognized and killed both GD2+ tumor-cells and VZV-infected cells, and limited the spread of infectious VZV in vitro. This ability to control viral spread may be an important safety feature for cancer patients who receive the live-attenuated VZV vaccine to boost their CAR-modified VZVSTs. Finally, we show that stimulation through the TCR, which can be achieved in vivo by vaccination, is able to partially rescue the anti-tumor activity of GD2.CAR-VZVSTs that are rendered dysfunctional by serial co-culture with neuroblastoma cell lines.

Materials and methods

Generation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs)

Dendritic cells (DCs) were derived from adherent PBMCs and cultured in CellGro DC medium (CellGenix, Freiberg, Germany) in the presence of interleukin (IL)-4 (1,000 U/mL) and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 800 U/mL; both R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). On day 5, immature DCs were matured for 48 hours using a cytokine cocktail consisting of IL-4, GM-CSF, IL-6 (10 ng/mL), TNF-α (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL; all R&D Systems), and PGE2 (1μg /mL; Sigma-Aldrich, Hayward, CA).

Activated T-cells (ATCs) for use as APCs were generated from PBMCs by stimulation on non-tissue-culture-treated 24-well plates coated with 1 μg/mL OKT3 (Ortho Biotech, Bridgewater, NJ) and 1 μg/mL anti-CD28 (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) antibodies in T-cell medium (50% RPMI 1640 [Hyclone], 45% EHAA [Life Technologies, Santa Ana, CA], 2 mM Glutamax and 5% human AB serum [Valley Biomedical Inc, Winchester, VA]) in the presence of human IL-2 (50 IU/mL, from the NCI Biological Resources Branch, Frederick MD) for 8 to 14 days. ATCs were restimulated with CD3 and CD28 antibodies to upregulate HLA and costimulatory molecules 2 days prior to use as APCs [26].

Generation of VZV-specific T-cells (VZVSTs)

PBMCs were pulsed with pepmixes (10 ng of each peptide per 106 PBMCs) for 60 minutes, then cultured in the presence of 400 U/mL of IL-4 and 10 ng/mL of IL-7 (R&D Systems) [27] for 9 days in 24-well plates. On days 9 and 16 of culture, effector T-cells were restimulated with autologous, irradiated (30 Gy), pepmix-pulsed ATCs (ATCpx) (10 ng of each peptide per 106 ATCs) and irradiated K562cs cells (VZVSTs:ATCpx:K562cs of 1:1:5) in 2 mL wells at 7x105 total cells per well with 5 ng/mL of IL-15 (R&D Systems). We termed this combination of stimulator cells KATpx for simplicity. ATCs upregulate CD80, CD86 and HLA class I and class II molecules after TCR stimulation and are able to present peptides to both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, while K562cs cells provide costimulation in trans [26].

GD2.CAR retroviral vector and transduction of VZVSTs

The 3rd generation GD2.CAR retroviral vector (GD2.CAR3) has been described previously [4, 28] and comprises the 14g2a ScFv [29], a short spacer from the CH2 domain of IgG1, a CD28 transmembrane and intracellular signaling domains from CD28, OX40 and CD3 ζ. For generation of GD2.CAR-VZVSTs, PBMCs were activated with pepmix-pulsed DCs in the presence of IL-4 and IL-7 and on day 2 transduced with the GD2.CAR retroviral vector on retronectin (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan)-coated plates, in the presence of IL-4 and IL-7. On day 4 cells were returned to regular culture, as described above.[30]

VZV infection of fibroblasts

VZV expressing the EGFP protein fused to the N terminal end of the ORF66 protein kinase [31] was maintained as infected cell stocks by culture with fresh MRC-5 cells and used to prepare VZV when cytopathic effects were observed. Cell free VZV was released by brief sonication and stored at −80°C until further use as previously described [25] [26]. For infectious spread assays, dermal fibroblasts were infected with cell-free VZV at 2 x 103 PFU per 1 x 106 cells. When cytopathic effects were observed in ~75% of cells (2 to 3 days), cells were harvested by trypsinization and added to uninfected cells to propagate the virus or to test the ability of VZVSTs to limit virus spread.

VZVST inhibition of virus spread in VZV infected fibroblasts

VZVSTs, PBMCs or autologous ATCs were co-cultured with GFP-VZV-infected fibroblasts and uninfected fibroblasts at a ratio of 1:7:20 in T-cell medium in the presence of recombinant human IL-2 (50 IU/mL) in 12 well-plate at 5.6x105 total cells per well. Three days later, cultures were collected and stained with CD45 antibodies (BD Biosciences), and analyzed by FACS. Absolute numbers of events for GFP positive infected cells are compared using CountBright™ Absolute Counting Beads (Invitrogen).

Co-culture experiments

GD2.CAR-VZVSTs or non-transduced (NT)-VZVSTs were co-cultured with LAN-1 cells at the ratio of 1:1 in T-cell medium without cytokines. Five days later, cultures were collected and stained with CD3 and 14g2a (anti-GD2) antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. For serial killing experiments, GD2.CAR-VZVSTs were co-cultured with GFP-ffluc-LAN1 cells at 1:1 ratio in the presence of IL-2 (20 U/mL) (1st co-culture). On Day 7, GD2.CAR-VZVSTs were harvested from the co-culture plates then were left unstimulated or were stimulated with autologous pepmix-pulsed DCs for 30 minutes at a 10:1 ratio of VZVSTs: DCs. After three days, T cells were plated at a 1:1 ratio with fresh GFP-ffluc-LAN1 cells in the presence of IL-2 (20U/mL) (2nd co-culture). Co-cultures without DCs were used as unstimulated controls. T-cells and tumor cells were counted by flow cytometry using CountBright beads.

RESULTS

VZV pepmixes and an antigen-presenting complex activate and expand VZVSTs

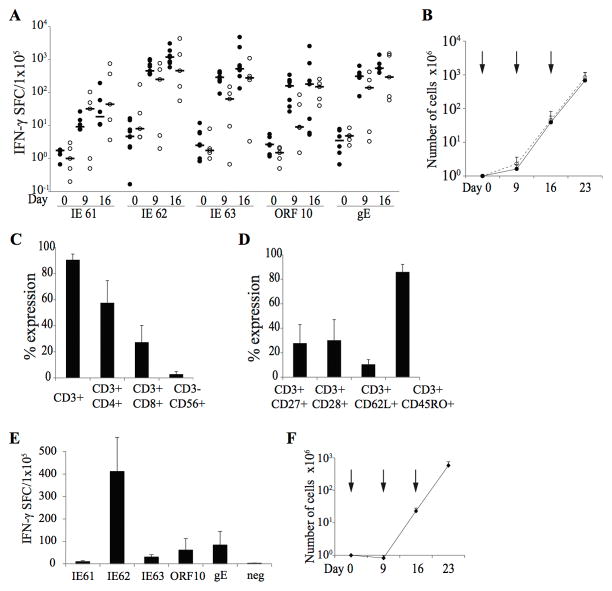

To determine if we could reactivate and expand VZVSTs from both naturally infected and vaccinated donors using overlapping peptide libraries (pepmixes), we stimulated PBMCs from 9 naturally infected (median age 34, range 22–55) and 5 vaccinated donors (median age 17, range 3–21, including three children aged 3, 5 and 17) with combined pepmixes spanning IE61, IE62, IE63, gE and ORF10 in the presence of IL-4 and IL-7. These antigens were chosen because they should be processed and presented to T cells before immune evasion genes of VZV can be expressed and because they had previously proved immunogenic [15, 16, 19, 21]. Responder cells were restimulated on day 9 using pepmix-pulsed, irradiated autologous ATCs combined with irradiated HLA-negative K562 cells genetically modified with CD80, CD86, 41BB-ligand and CD83 (K562cs) to provide costimulation in trans [26], an antigen-presenting complex we termed KATpx. IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were performed on fresh PBMCs at the end of each stimulation cycle on days 9 and 16. Low frequencies of VZVSTs, usually less than 10 spot forming cells (SFC) per 105 cells were detected in fresh PBMCs from both naturally infected and vaccinated donors, (Figure 1A). However, these frequencies increased rapidly over the next 9 to 16 days in response to peptide stimulation (Figure 1A). The majority of individuals showed some response to all five antigens, but the strongest responses were to IE62 (median 1184 SFC/1x105 cells, range 584-3073), IE63 (median 521 SFC/1x105 cells, range 133-4771) and gE (median 542 SFC/1x105 cells, range 399–1400 on day 16), while IE61 induced weaker responses (median 19 SFC/1x105 cells, range 11-194). VZVSTs increased not only in frequency but also in absolute numbers as total cell numbers increased more than 3-logs over 23 days (Figure 1B). We observed no obvious differences in the specificity or proliferation of VZVSTs cells expanded from the 9 donors who had been naturally infected and the 5 who had been vaccinated. Expanded cells were predominantly CD3+ T cells (90.6±4.3%), with a majority of CD4+ T cells (57.6±16.9%) as previously reported [13, 15–17, 19, 34, 35] and a minority CD8+ T-cell component (27.4±12.9%) (Figure 1C). The majority of CD3+ T-cells expressed markers that were transitional between central memory and effector memory cells expressing CD45RO+/CCR7−/CD62L+ or CD45RO+/CCR7−/CD28+ at the end of the third stimulation (Figure 1D). These data demonstrate our ability to manufacture T-cells specific for all five of the selected VZV antigens using the strategy proposed.

Figure 1. VZVSTs can be reactivated and expanded from the peripheral blood of healthy donors and cancer patients.

(A) VZVSTs were generated from donors immunized by natural infection (n=9) or by VZV vaccination without history of natural infection (n=5). The frequency of antigen-specific T-cells in peripheral blood was determined by IFN-γ release ELISPOT assay after overnight stimulation of PBMCs with VZV antigen-spanning pepmixes (Day 0) and again on days 9 and 16. Closed circles (●) represent naturally infected donors and open circles (○) are vaccinated donors. (B) T cell expansion was evaluated by viable cell counting using trypan blue exclusion. Solid line represents naturally infected donors (n=9) and dashed line, vaccinated donors (n=5). Results are shown as mean cell numbers ± SEM. Each arrow indicates each stimulation. (C and D) The expression of surface markers as a percentage of the live cells was assessed on day 16 (n=6). Results are shown as mean ± SD. (E and F) PBMCs from 6 cancer patients including three pediatric patients were stimulated with VZV pepmix-pulsed mature DCs. Results from the five responders are shown. (E) Specificity on day 16 was measured by IFN-γ release ELISPOT assay (mean ± SEM, n=5). (F) Cell expansion was evaluated by counting using trypan blue exclusion. Results are shown as mean cell numbers ± SEM (n=5). Each arrow indicates each stimulation.

VZVSTs can be generated from cancer patients

Since our ultimate goal was to generate autologous GD2.CAR-VZVST for clinical use, we generated VZVSTs from 6 patients with osteosarcoma (median age 19.5, range 10–53) and measured the frequency of VZV antigen-specific cells on day 16 in IFN-γ ELISPOT assays. In 5 of the 6 patients, we successfully demonstrated VZV antigen specificity (Figure 1E). The expanded T-cells from only one patient lack VZV antigen specificity as determine by IFN- ELISPOT assay (data not shown); we do not know the VZV serostatus of this patient. Over 23 days of culture, patient-derived VZVSTs expanded by 581 ± 372-fold (Figure 1F). Although this rate of expansion was lower than for healthy adults, sufficient T-cells for multiple doses on our highest clinical dose level (108 per m2) could readily have been achieved from 5 of the 6 patients, suggesting that the manufacturing strategy used is sufficiently robust to produce VZVSTs for clinical use in cancer patients. [36]

Circulating VZVSTs increase after VZV booster vaccination

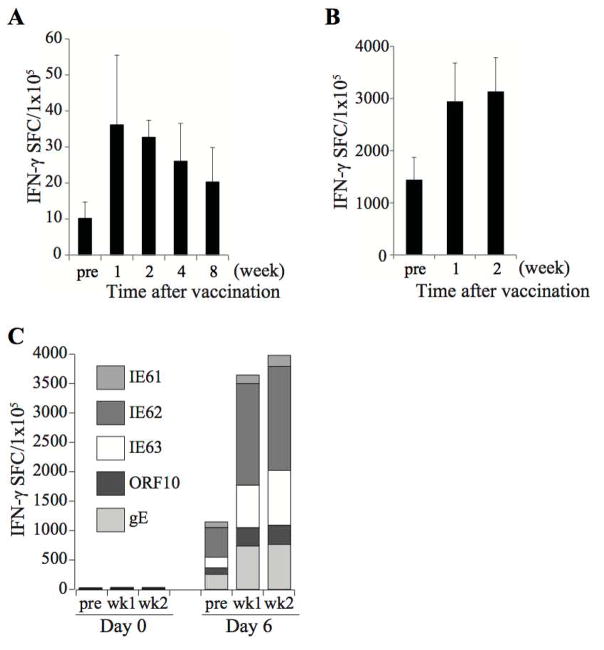

Since we plan to use VZV vaccination to boost the frequency of GD2.CARs-VZVSTs in patients, it was important to show that T-cells specific for the chosen antigens expand in vivo in response to VZV vaccination. Therefore, we compared the frequency of VZVSTs in PBMCs before and after administration of the VZV booster vaccine ZOSTAVAX to 3 seropositive adults. While the frequencies of VZVSTs before VZV vaccination were low (mean 10.2 ± 4.6 SFC/1x105 PBMCs, n=3), frequencies increased to 36.1 ± 19.3 SFC/1x105 PBMCs within one week and remained elevated for over 8 weeks (Figure 2A). Although responses observed after direct stimulation of PBMC were low, after 4 to 6 days of in vitro expansion with VZV pepmixes in the presence of IL-4 and IL-7, clear differences between pre- and post-vaccination were discerned and persisted for at least 8 weeks (Figures 2B and 2C). The responses from individual donors are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. These data show that VZV vaccination increases the in vivo frequency of T-cells specific for the chosen VZV antigens.

Figure 2. Circulating VZVSTs are increased in response to VZV booster vaccination.

PBMCs drawn before and at intervals after immunization of seropositive adults with the VZV booster vaccine, Zostavax, were stimulated with VZV antigens. The frequency of antigen-specific T-cells in peripheral blood was determined by IFN-γ release ELISPOT assay. (A) Frequency of VZVSTs shown after 24 hours of stimulation and (B) after restimulation with pepmixes 4 days later in one donor and 6 days later in 2 donors. The background frequency of IFN-γ-secreting T-cells was subtracted from the specific responses. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n=3). (C) The response to each antigen of one of three vaccinated donors.

VZVSTs prevents infectious VZV spread in fibroblasts

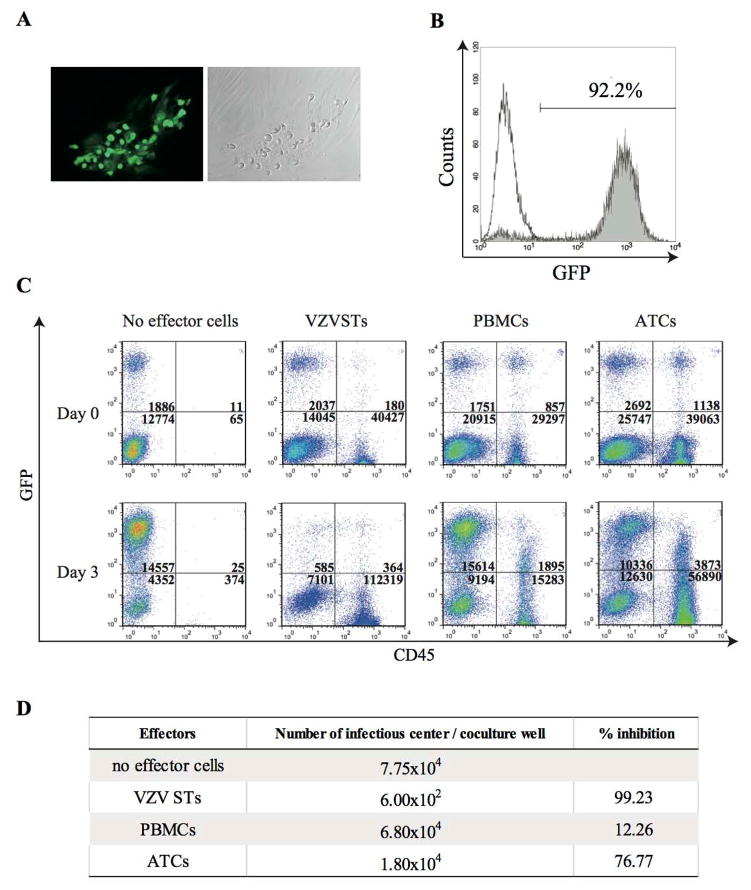

To determine if expanded VZVSTs had biological activity against live VZV, we established a VZV infectious spread cell model using a GFP-tagged VZV (GFP-VZV) in dermal fibroblasts. VZV spreads almost exclusively by cell-to-cell spread involving membrane fusion, and is normally propagated by co-culture of infected and uninfected cells. Although the complete VZV replication cycle takes from 9 to 12 hours, cytopathic effects may not appear for up to two days. However, GFP-VZV infection can be readily be detected by monitoring GFP expression early after infection (Figure 3A). After two passages in which uninfected fibroblasts and fresh medium were added to the infected cultures, over 90% of cells were GFP+ve (Figure 3B). To determine if VZVSTs could inhibit virus spread within the cocultures, VZV-infected dermal fibroblasts were co-cultured with uninfected autologous fibroblasts and autologous VZVSTs at a ratio of 1:7:20. CD56+ cells were depleted from VZVSTs using CD56 microbeads prior to co-culture to ensure that any activity was derived from T-cells. Autologous PBMCs and autologous CD3/28-activated ATCs were used as control effector cells. After 3 days of culture, the degree of VZV spread within each co-culture well was quantified by flow cytometry in the presence of counting beads. Effector cells (VZVSTs, PBMCs, and ATCs) were distinguished from fibroblasts by CD45 expression. In VZV-infected co-cultures without effector cells, the number of GFP+ infected fibroblasts increased about 7.7 fold (Figure 3C). Virus spread was unaffected by the presence of PBMC (8.9 fold increase) and was only partially inhibited by CD3/28-activated T-cells (3.8 fold increase). However, in the co-cultures with VSVSTs, the number of infected fibroblasts decreased by over 70% compared to cultures without effector cells. In order to quantify this virus inhibition, we measured the number of infected cells in each co-culture in an infectious center assay. As shown in Figure 3D, VZVSTs prevent infectious spread effectively, while PBMCs and ATCs had little protective capacity. Of note, 11% of PBMCs and 6% of ATCs became infected with VZV during the co-culture, as measured by GFP expression in CD45+ cells, while VZVSTs remained uninfected (0.3%) (Figure 3C). Further, VZVSTs expanded by 2.8 fold during the culture with autologous VZV infected fibroblast, while PBMCs decreased in number (0.6 fold) and ATC number increased by 1.5 fold.

Figure 3. VZVSTs prevent infectious virus spread.

(A) GFP-tagged, VZV-infected dermal fibroblasts were used as targets. Infected fibroblasts were GFP positive and a fraction show cytopathic effect. (B) Frequency of infected fibroblasts as measured by GFP expression. (C) GFP-tagged VZV-infected fibroblasts, fresh uninfected fibroblasts and effector cells were co-cultured at the ratio of 1:7:20. Three days later, cultures were collected and stained with CD45 antibodies, and analyzed by FACS. Indicated are the absolute numbers of events for GFP positive VZV-infected cells. (D) Infectious center assay. % inhibition was calculated as (number of infectious center in each test condition / number of infectious center in controls without effectors) x 100. VZVSTs prevent infectious spread, while PBMCs and ATCs had little protective capacity.

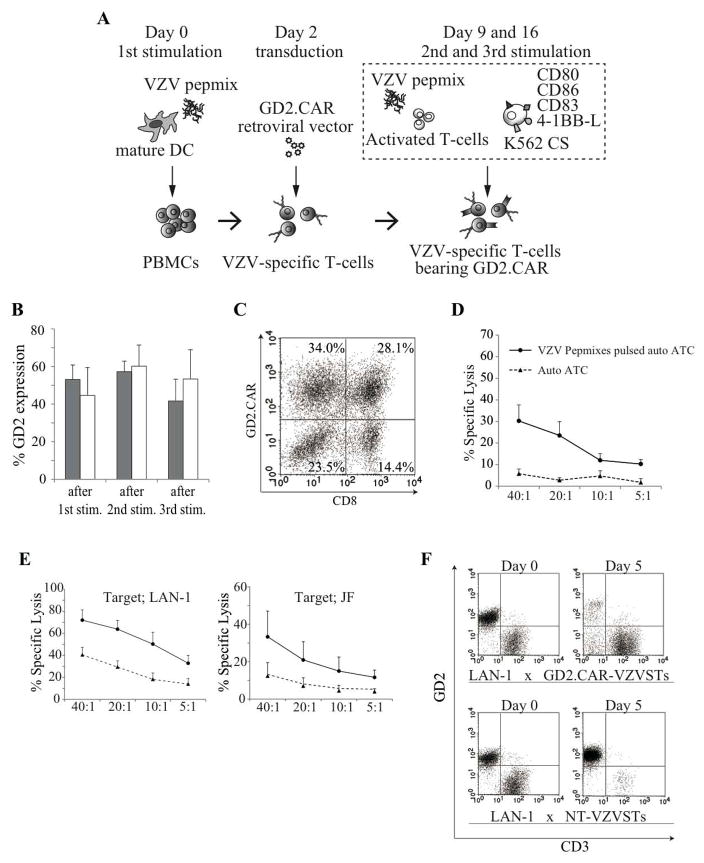

VZVSTs can be transduced with CARs and stably express the transgene during expansion

VZVSTs generated from donors either naturally infected with VZV (n=3) or immunized by vaccination and without history of natural infection (n=3), were transduced with a retroviral vector encoding a 3rd generation GD2.CAR two days after the first stimulation in the presence of IL4 and IL-7. This previously described CAR includes costimulatory endodomains from CD28 and OX40, and is currently under evaluation in clinical trials [36]. The efficiency of transduction was increased when pepmix-pulsed DCs were used for the first stimulation (not shown). The second and third stimulations were performed on days 9 and 16 using KATpx (as illustrated in Figure 4A). Transgene expression was evaluated by flow cytometry using the GD2.CAR (14g2a)-specific anti-idiotype antibody (1A7) after the 1st, 2nd and 3rd stimulations. The GD2.CAR was expressed in 53.1% ± 7.7% of VZVSTs from naturally infected donors and 44.6% ± 14.8% of VZVSTs from immunized donors on day 9 after the first stimulation. CAR expression was maintained over the second and third stimulations (Figure 4B). CD8-positive and -negative T cells were transduced with similar efficiency (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) can be expressed in VZVSTs, maintained over three stimulations and have functional specificity for both VZV and GD2.

(A) Diagram of GD2.CAR-VZVST generation. (B) GD2.CAR expression on transduced VZVSTs was measured using the 14g2a-specific anti-idiotype antibody (1A7) after the 1st, 2nd and 3rd stimulations. T cell lines from donors either naturally infected with VZV ■ (n=3) or immunized by vaccination (n=3) were assessed. Results are shown as mean % of expression ± SD. (C) One representative dot blot showing expression of the GD2.CAR. (D) VZV pepmix-pulsed autologous activated T-cells (ATCs) were labeled with 51Cr and cultured with the transduced VZVSTs for 6 hours at the effector target ratios shown (solid lines). Control targets were autologous ATCs (dotted lines). Results are shown as mean of % specific lysis ± SEM (n=4). (E) GD2-positive NB cells (LAN-1 and JF) were labeled with 51Cr and cultured with GD2.CAR-transduced VZVSTs (solid lines) or non-transduced VZV-specific T cells (dotted lines) for 6 hours at the effector target ratios shown. Results are shown as mean of % specific lysis ± SEM (n=3). (F) GD2.CAR-VZVSTs and NT-VZVSTs were co-cultured with LAN-1 cells at the ratio of 1:1. Five days later, cultures were stained with CD3 and GD2 antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

GD2.CAR-VZVSTs kill both VZV- and GD2-expressing target cells

To demonstrate that GD2.CAR-modified VZVSTs have functional specificity for both VZV and GD2 antigens, transduced-VZVSTs were co-cultured for 6-hours with 51Cr-labeled GD2-positive and VZV antigen-expressing target cells. GD2.CAR-VZVSTs killed both GD2-positive NB cells (LAN-1 and JF) and VZV pepmix-pulsed autologous activated T cells (auto ATCs), but not unpulsed autologous ATCs (Figures 4D and 4E). NT-VZVSTs showed relatively low levels of killing of GD2-positive, VZV-negative NB cells. Longer-term co-cultures of GD2.CAR-VZVSTs and neuroblastoma cell lines were also performed to evaluate the effects of the GD2.CAR on T-cell proliferation in response to GD2. GD2.CAR-VZVSTs co-cultured with LAN-1 cells without cytokines at the ratio of 1:1 expanded in numbers and eliminated the majority of LAN-1 cells by day 5, while LAN-1 cells grew out in co-cultures with NT-VZVSTs, and NT-VZVST numbers decreased (Figure 4F).

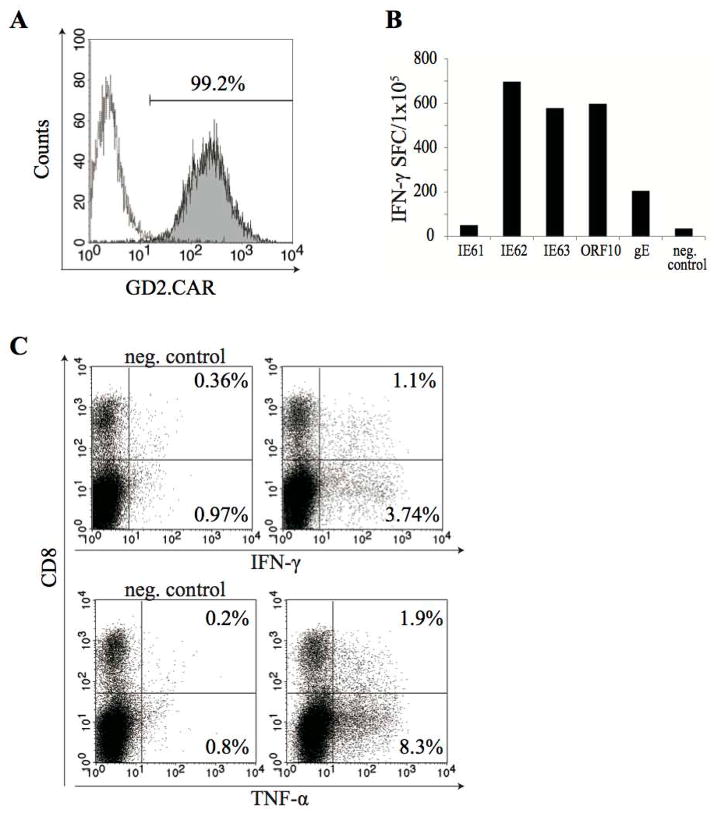

To ensure that individual VZVSTs modified with GD2.CARs were bispecific and retained functional specificity for VZV, GD2.CAR-positive cells were selected from the bulk population using the 14.g2a idiotype-specific antibody 1A7 (mouse IgG1) and anti-Mouse IgG1 microbeads. After resting for 48 hours, the purity of the sorted GD2.CAR positive cells was confirmed by FACS; over 99% of T-cells expressed the GD2.CAR (Figure 5A). VZV antigen-specificity was then determined using IFN-γ ELISPOT assays and intracellular cytokine staining. Sorted GD2.CAR+ T-cells cells that were stimulated with VZV pepmixes produced IFN-γ in ELISPOT assays (>2000 spot forming cells per 105 T-cells) (Figure 5B). IFN- and TNF-α–secreting cells were also observed in both CD8+ and CD8- populations by intracellular cytokine staining after stimulation with VZV pepmixes (Figure 5C). These results showed that GD2.CAR-modified cells were functionally bispecific.

Figure 5. Transduced T-cells are bi-specific.

GD2.CAR-VZVSTs were stained with the 14.g2a-specific idiotype antibody 1A7 (mouse IgG1) and sorted with Anti-Mouse IgG1 MicroBeads. Sorted cells were rested 48 hours in incubator. (A) Purity of sorted cells was tested after 48 hours incubation. (B) The VZV antigen-specificity of the sorted cells from one of the two donors tested is shown and was determined using IFN-γ release ELISPOT assays. (C) Sorted cells were stimulated with VZV antigen pepmixes and IFN-γ or TNF-α production was evaluated by intracellular cytokine staining. One representative of two donors is shown.

CAR-VZVSTs exposed to tumor cells become dysfunctional via their CAR, but retain responsiveness to their VZV-specific TCR

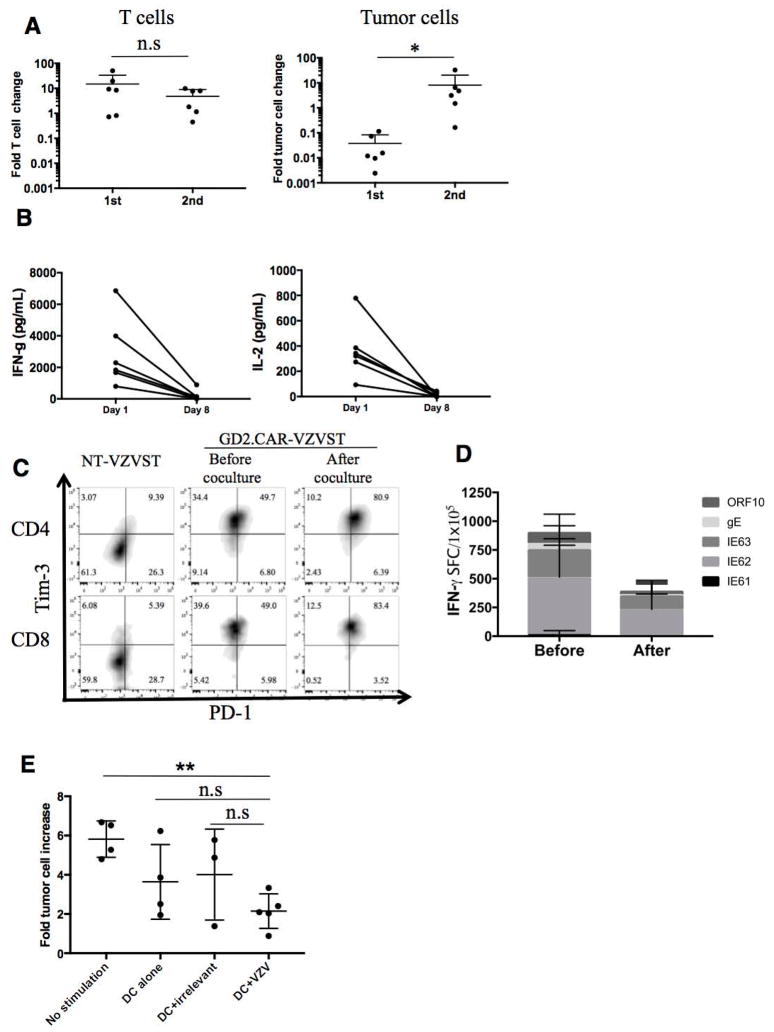

GD2.CAR-VZVSTs killed LAN-1 tumor cells on their first encounter in co-culture assays but if the co-cultured GD2.CAR VZVSTs were harvested and exposed to fresh LAN-1 cells, they were still able to expand but no longer able to control tumor cells (p=0.03) (Figure 6A and supplementary Figure 2A). IFN–γ and IL-2 secretion was also significantly diminished after the second co-culture compared to the first co-culture, as measured by ELISA (Figure 6B). This phenomenon was not unique to VZVSTs; GD2.CD28OX40z CAR-modified CD3/28-activated T-cells also lost their ability to secrete IFN–γ after the second coculture (Supplementary figure 2B). When we evaluated VZVSTs modified with GD2.CARs expressing other endodomains (GD2.z, GD2.CD28z, and GD2.41BBz), we observed the same phenomenon, with decreased IFN-γ secretion and loss of tumor cell killing after the second coculture (Supplementary figure 2C). Lack of responsiveness to the CAR could not be explain by loss of the CAR, since VZVSTs cocultured with tumor cells retained CAR expression as determined by flow cytometry. Indeed as illustrated for one representative donor, the frequency of CAR-modified VZVSTs increased from 48.9% to 84.5% and the MFI increased from 951 to 3430 after coculture (Supplementary Figure 2D). GD2.CAR VZVSTs expressed high levels of TIM 3 compared to non-transduced cells, even prior to coculture and did not change after coculture with tumor cells, while expression of PD1 increased. However, the T-cells were not exhausted because they remained responsive to TCR stimulation (Figure 6D) and proliferated even in response to repeat CAR stimulation (Figure 6A). Thus the T-cells displayed dysfunction via their CAR, but retained a functional response to the TCR.

Figure 6. CAR-VZVSTs became exhausted by stimulation through the CAR but the TCRs were still functional.

(A) GFP-ffluc-LAN1 (GFP+) and T cell (CD3+) were analyzed quantitatively after the 1st and 2nd co-cultures. The fold change of T cell or tumor cell numbers between the end of 1st coculture and the end of 2nd coculture are shown. (n=6, mean ± SD) (B) Cytokine secretion from GD2.CAR-VZVST after encountering LAN1 cells. T cells and LAN1 cells were plated at 1:1 ratio and after 24 hours supernatants were collected for ELISA. On day 7, T cells were harvested and replated with LAN1 cells at the same E:T ratio. Supernatants were collected on Day 8 (24 hours after 2nd co-culture) and then IFN-γ and IL-2 concentrations were measured. (n=6) (C) PD-1 and Tim-3 expression on non-transduced VZVST, GD2.CAR-VZVST before or 7 days after coculture with LAN1 cells are shown. GD2.CAR VZVST were gated on CAR+ and CD4+ or CD8+. Dot plots from one representative donor of two are shown. (D) The frequency of antigen-specific T-cells before and after coculture with LAN1 was determined by IFN-γ release ELISPOT assay after overnight stimulation with VZV antigen-spanning pepmixes. Data denote mean ± SD (n=3). (E) After the 2nd co-culture, T cells were harvested and cultured with VZV pepmix loaded DCs, irrelevant pepmix loaded DCs, DCs alone, or no stimulation for three days and then co-cultured with fresh GFP-ffluc-LAN1 cells. The fold tumor cell increase on day 7 to day 0 are shown. Data denote mean ± SD (n=4, no stimulation, DC alone; n=3, DC+irrelevant pepmix, n=5, DC+VZV pepmix).

To determine if the anti-tumor activity of GD2.CAR-VZVSTs could be restored by stimulation through their TCR, they were first co-cultured with GFP-modified LAN-1 cells for 7 days (first co-culture) and then restimulated with DCs pulsed with VZV or irrelevant pepmixes for 3 days in the presence of IL-2 (20U/mL) prior to co-culture with fresh GFP-ffluc LAN-1 cells (second co-culture). During the first co-culture LAN-1 cells were eliminate. Although subsequent stimulation with DCs did not fully restore the anti-tumor function of GD2.CAR-VZVSTs, GD2.CAR-VZVSTs restimulated with VZV pepmix-pulsed DCs showed significantly greater tumor control compared to GD2.CAR-VZVSTs that received no interim stimulation (p< 0.01) (Figure 6E). However, DCs alone or pulsed with irrelevant an pepmix also partially rescued LAN-1 cultured GD2.CAR-VZVSTs, as did supernatants from VZV pepmix-pulsed DCs and CD3 antibody alone or combined with CD28 antibody (Supplementary figure 2E). These results suggest that restoration of the anti-tumor activity of GD2.CAR-T-cells could be produced by a range of proinflammatory signals. VZV vaccination might therefore restore the function of CAR-T cells rendered dysfunctional by the tumor, whether VZV-specific or not. However, only VZV-specific T-cells should accumulate at the site of VZV vaccination where they will be exposed to proinflammatory conditions.

DISCUSSION

The VZV antigens, gE, IE62, IE63, IE61 and ORF10 are known immunodominant antigens of VZV [37], and we have shown that T-cells specific for these antigens can be expanded to clinically relevant numbers from healthy donors and cancer patients, whether vaccinated or naturally infected. T cells specific for all five antigens increased in frequency in response to vaccination and should therefore be suitable carriers for tumor-specific CARs in clinical trials that evaluate the ability of VZV vaccination to boost the frequency and function of CAR-modified VZVSTs. GD2.CAR expression was stable over at least three in vitro stimulations and we demonstrated dual specificity of transduced T-cells for both GD2 and VZV. As shown by other groups, the majority of the VZVSTs were CD4+ T-cells [37], but they were able to kill both GD2+ tumor cells and VZV-infected cells and inhibited the spread of infectious VZV in autologous fibroblast cultures. Culture of GD2.CAR VZVSTs (or CD3/28-activated T-cells) with live tumor cells resulted in T-cell dysfunction, so that T-cells lost their ability to secrete cytokines and kill tumor cells on exposure to fresh tumor cells. However, GD2.CAR-VZVSTs remained responsive to stimulation via the TCR, and APCs pulsed with VZV peptides could restore the ability of GD2.CAR-VZVSTs to eliminate neuroblastoma cells in serial co-cultures. Partial reversal of CAR dysfunction could also be induced by DCs alone and antibodies to CD3 and CD28, suggesting that a proinflammatory milieu may be able to restore tumor-specific T-cell dysfunction. These data establish many of the parameters for developing a therapy using GD2.CAR-modified VZVSTs for patients with GD2-positive tumors (NCT01953900).

This work expands upon earlier studies that demonstrated the potential of harnessing the potent immune activity of VSTs for CAR therapy. First generation GD2.CAR-modified EBVSTs circulated with a higher frequency in patients with neuroblastoma than similarly modified CD3-activated T-cells, producing 3 complete tumor responses among 11 patients with relapsed disease. However, in these patients, none of whom showed EBV reactivation, there was no expansion of CAR.EBVSTs in blood and patients with bulky disease did not enter remission. This lack of evident expansion may stem from the fact that patients were not lymphodepleted and EBV was well controlled, limiting the supply of viral antigens for T-cell expansion. Herpesvirus reactivation in vivo is an uncontrollable and possibly rare event, while T-cell activation by vaccination allows for precise and potent timing of T-cell stimulation. The use of VZVSTs instead of EBVSTs allows us to take advantage of the commercially available VZV vaccine to provide extratumoral T-cell boosting in a proinflammatory environment, and may perhaps obviate the need for cytotoxic lymphodepletion. An attractive feature of this live attenuated viral vaccine is that it replicates in infected cells and continues to produce viral proteins in an inflammatory environment for some time, in contrast to any subunit vaccine. In this study, we used a third generation CAR,[28] that should also enable intratumoral proliferation upon CAR engagement and provide resistance to tumor derived inhibitory factors.

CAR-modified VZVSTs used in combination with VZV vaccination for the treatment of patients with cancer must fulfill several requirements: CAR-VZVSTs must increase in frequency in response to VZV vaccination in a majority of individuals, they must be able to kill tumor cells expressing the CAR ligand, and they should be able to protect cancer patients, who may be immunocompromised as a result of prior chemotherapy or their immunosuppressive tumors, from the live-attenuated VZV vaccine. Therefore it is important to choose viral antigens that induce protective T-cells. Such VZV antigens must be processed and presented by infected cells before viral immune evasion proteins take effect, and mediate killing of infected target cells before new infectious virus particles are produced. This is particularly important for VZV, which is able to infect and kill T-cells and DCs [38]. Candidate antigens would be abundant virion proteins, such as gE and ORF10 that are introduced into the cell during the infection process, IE61 and IE62 that are the earliest proteins to be expressed after infection, and IE63 that is expressed on reactivation of VZV from latency in neurons and, together with IE62, is present in virions. T-cells specific for all of these proteins have already been identified in seropositive individuals [15, 16, 39, 40], and we all of our donors, whether they achieved their immunity naturally or after vaccination, reacted with most of these viral proteins. Although ELISPOT assays indicated that the frequency of VZV antigen-specific T-cells was only around 2% to 5%, this assay underestimates the true frequency of activated antigen-specific by about 10 to 100 fold, as can be determined if T-cells specific for a specific peptide epitope are quantified by both ELISPOT and tetramer assays.[29]

T cells specific for all five VZV antigens increased in frequency after vaccination of healthy seropositive adult donors who had been infected naturally during childhood, with the most robust increases seen in T cells specific for IE62, IE63 and gE. Over 100-fold VZVST-expansion, representing 6 to 7 antigen-specific T-cell doublings, was seen in all three vaccinated donors within 6 days of ex vivo stimulation. Hence, T-cells specific for these antigens should be suitable as carriers of tumor-specific CARs. The ability of pepmix-activated VZVSTs to prevent the spread of infectious virus in autologous fibroblasts, suggests that they should provide anti-viral protection to recipients with cancer who are immunosuppressed as a result of their tumor or their prior cytotoxic chemotherapy. Anti-viral protection is an important factor, as VARIVAX is contraindicated in individuals with hematopoietic malignancies or who are immunosuppressed. Although our group has shown that pepmix-activated VSTs can control reactivations of CMV, EBV, adenovirus and BK virus in immunosuppressed HSCT recipients,[41] the ability of VZVSTs protect against VZV infection or reactivation has yet to be demonstrated.

GD2.CAR-VZVSTs were able to kill neuroblastoma cell lines in coculture, but if harvested from the co-culture with tumor cell lines and added to fresh tumor cells, they lost their ability to kill tumor cells and secrete cytokines in response to CAR stimulation. Long, AH, et al. (2016) [42] reported that 14g2a-CARs spontaneously dimerize via the ScFv resulting in tonic signaling and leading to cell differentiation and exhaustion [43]. Our GD2.CAR construct differs in spacer, transmembrane and costimulatory endodomains and GD2.CAR-VZVSTs did not become exhausted, since they remained responsive to TCR stimulation and did not become dysfunctional unless exposed to GD2. This phenomenon was previously demonstrated by Stotz et al., who showed that two different TCRs expressed in a murine hybridoma functioned independently, so that “anergy” in one TCR did not affect signaling through the other [44]. Importantly, even if CAR dysfunction was induced via GD2 stimulation, GD2.CAR-VZVSTs continued to respond to VZV pepmix-pulsed DCs and partially regained their ability to kill GD2+ tumor cells. This rescue did not require cognate antigen and as shown in supplementary Figure 1, DCs alone and supernatants from mature DC were able to increase the function of the CAR on subsequent culture with tumor cells. Vaccination with a live virus such as VZV can provide prolonged exposure to professional antigen-presenting cells by inducing innate signals for T-cell recruitment to the vaccine site, followed by strong antigen-specific stimulation and costimulation. Our results also demonstrate that T-cells can be unresponsive to a CAR, while remaining responsive to their TCR.

Our serial coculture experiment revealed a common problem with CAR T-cells, which are apparently functional in their ability to proliferate and kill after a single exposure to tumor. Unless these T-cells are re-exposed to tumor, their dysfunction may never become apparent. In our first attempts to rescue dysfunctional GD2.CAR-VZVSTs, we used VZV-infected autologous fibroblasts to provide TCR stimulation in cocultures with neuroblastoma cell lines. However, VZV rapidly infected and destroyed the neuroblastoma cell. Therefore, VZV vaccination of patients with relapsed tumors may have an additional benefit as an oncolytic virus. Use of VZV in this manner was suggested by Leske et al, who showed that VZV replicated efficiently in primary malignant gliomas and glioma cell lines.[45] VZV is also known to infect and replicate in T-cells and although VZV infected PBMCs and non-specifically activated T-cells in the virus spread assay, VZVSTs did not become infected. Either activated VZVSTs are resistant to infection or, as suggested by our results, they retained function and killed infected cells before they could release infectious virus. This likely explains our observation that non-specifically activated T-cells were susceptible to virus infection in cocultures, while VZVSTs were not.

Our proposed strategy for combining GD2.CAR-VZVSTs with VZV vaccination would likely not be effective for VZV seronegative patients, since it is difficult, to generate VSTs from seronegative donors. Although most children in the U.S. are vaccinated between the ages of 12 to 24 months, about one third of children are diagnosed with neuroblastoma before the age of one.[46] However, strategies for reactivating VSTs from seronegative individuals have been published [47, 48], and these T-cells have been evaluated in clinical trials [49]. Additionally, our CAR-modified antigen-specific T-cell combination strategy would be applicable for any cytotoxic T-cell antigen for which there is a vaccine and could be adapted to CARs of any specificity.

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

We have generated GMP compliant T cells that are specific for varicella zoster virus (VZV) via their native TCR and for the disialoganglioside, GD2, via a chimeric antigen receptor (GD2.CAR), so that in vivo expansion and persistence can be induced by VZV vaccination in patients with GD2-positive tumors, such as neuroblastoma or sarcoma. The VZV vaccine should overcome the lack of immunogenicity of solid tumors by providing potent extra-tumoral stimulation of CAR-modified VZV-specific T-cells (CAR-VZVSTs) and should promote their function despite the inhibitory tumor environment. CAR T-cells may become dysfunctional on exposure to tumors and fail to kill tumor cells after their first encounter in vitro. We show that GD2.CAR-VZVSTs rendered dysfunctional by exposure to neuroblastoma cell lines can be partially rescued by stimulation via the TCR.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in parts by a grant from Japanese Foundation for Pediatric Research to M.T., NIH-NCI PO1 CA94237, Alex’s lemonade Stand Foundation and the V-Foundation. PRK was supported by PHS awards NS064022, EY08098, and unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc and the Eye & Ear Institute of Pittsburgh.

This work was supported in parts by a grant from Japanese Foundation for Pediatric Research (to M.T), NIH-NCI PO1 CA94237, Alexs lemonade Stand Foundation and the V-Foundation. PRK was supported by PHS awards NS064022, EY08098, and unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness Inc and the Eye & Ear Institute of Pittsburgh. We thank Catherine Gillespie for expert editing and Kathan Parikh for technical support.

Footnotes

Additional methodology can be found in the Supplement.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest

- Conception and design: MT, HT, CR, CMR

- Development of methodology: MT, HT, MN, JA, GD, AML, CR, CMR

- Acquisition of data: MT, HT, BM

- Analysis and interpretation of data: MT, HT, NL, BO, MN, JA, PRK, CMR

- Writing, review and/or revision of the manuscript: MT, HT, NL, MN, JA, GD, PRK, AML, CR, CMR

- Administrative, technical, or material support: GD, NL, BO, PRK,

- Study supervision: CMR

Reference List

- 1.Maude SL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang LC, et al. Overcoming intrinsic inhibitory pathways to augment the antineoplastic activity of adoptively transferred T cells: Re-tuning your CAR before hitting a rocky road. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(11):e26492. doi: 10.4161/onci.26492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilham DE, et al. CAR-T cells and solid tumors: tuning T cells to challenge an inveterate foe. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(7):377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossig C, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-specific human T lymphocytes expressing antitumor chimeric T-cell receptors: potential for improved immunotherapy. Blood. 2002;99(6):2009–2016. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pule MA, et al. Virus-specific T cells engineered to coexpress tumor-specific receptors: persistence and antitumor activity in individuals with neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1264–1270. doi: 10.1038/nm.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis CU, et al. Antitumor activity and long-term fate of chimeric antigen receptor-positive T cells in patients with neuroblastoma. Blood. 2011;118(23):6050–6056. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-354449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rooney CM, et al. Infusion of cytotoxic T cells for the prevention and treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-induced lymphoma in allogeneic transplant recipients. Blood. 1998;92(5):1549–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heslop HE, et al. Long-term outcome of EBV-specific T-cell infusions to prevent or treat EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease in transplant recipients. Blood. 2010;115(5):925–935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerdemann U, et al. Rapidly generated multivirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the prophylaxis and treatment of viral infections. Mol Ther. 2012;20(8):1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galea SA, et al. The safety profile of varicella vaccine: a 10-year review. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(Suppl 2):S165–9. doi: 10.1086/522125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Pathogenesis and current approaches to control of varicella-zoster virus infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(4):728–43. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00052-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagliardi AM, et al. Vaccines for preventing herpes zoster in older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008858. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008858.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergen RE, et al. Human T cells recognize multiple epitopes of an immediate early/tegument protein (IE62) and glycoprotein I of varicella zoster virus. Viral Immunol. 1991;4(3):151–166. doi: 10.1089/vim.1991.4.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadzot-Delvaux C, Arvin AM, Rentier B. Varicella-zoster virus IE63, a virion component expressed during latency and acute infection, elicits humoral and cellular immunity. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(Suppl 1):S43–S47. doi: 10.1086/514259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones L, et al. Phenotypic analysis of human CD4+ T cells specific for immediate-early 63 protein of varicella-zoster virus. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(12):3393–3403. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malavige GN, et al. Varicella zoster virus glycoprotein E-specific CD4+ T cells show evidence of recent activation and effector differentiation, consistent with frequent exposure to replicative cycle antigens in healthy immune donors. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152(3):522–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malavige GN, et al. Rapid effector function of varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein I-specific CD4+ T cells many decades after primary infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(5):660–664. doi: 10.1086/511274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black AP, et al. Immune evasion during varicella zoster virus infection of keratinocytes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e941–e944. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frey CR, et al. Identification of CD8+ T cell epitopes in the immediate early 62 protein (IE62) of varicella-zoster virus, and evaluation of frequency of CD8+ T cell response to IE62, by use of IE62 peptides after varicella vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(1):40–52. doi: 10.1086/375828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arvin AM, et al. Early immune response in healthy and immunocompromised subjects with primary varicella-zoster virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1986;154(3):422–429. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arvin AM, et al. Equivalent recognition of a varicella-zoster virus immediate early protein (IE62) and glycoprotein I by cytotoxic T lymphocytes of either CD4+ or CD8+ phenotype. J Immunol. 1991;146(1):257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asanuma H, et al. Frequencies of memory T cells specific for varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and cytomegalovirus by intracellular detection of cytokine expression. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(3):859–866. doi: 10.1086/315347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giller RH, Winistorfer S, Grose C. Cellular and humoral immunity to varicella zoster virus glycoproteins in immune and susceptible human subjects. J Infect Dis. 1989;160(6):919–928. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.6.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landmeier S, et al. Gene-engineered varicella-zoster virus reactive CD4+ cytotoxic T cells exert tumor-specific effector function. Cancer Res. 2007;67(17):8335–8343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suhoski MM, et al. Engineering artificial antigen-presenting cells to express a diverse array of co-stimulatory molecules. Mol Ther. 2007;15(5):981–988. doi: 10.1038/mt.sj.6300134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngo MC, et al. Complementation of antigen-presenting cells to generate T lymphocytes with broad target specificity. J Immunother. 2014;37(4):193–203. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerdemann U, et al. Generation of multivirus-specific T cells to prevent/treat viral infections after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J Vis Exp. 2011;(51) doi: 10.3791/2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pule MA, et al. A chimeric T cell antigen receptor that augments cytokine release and supports clonal expansion of primary human T cells. Mol Ther. 2005;12(5):933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mujoo K, et al. Functional properties and effect on growth suppression of human neuroblastoma tumors by isotype switch variants of monoclonal antiganglioside GD2 antibody 14.18. Cancer Res. 1989;49(11):2857–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, et al. Early transduction produces highly functional chimeric antigen receptor-modified virus-specific T-cells with central memory markers: a Production Assistant for Cell Therapy (PACT) translational application. J Immunother Cancer. 2015;3:5. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisfeld AJ, et al. Downregulation of class I major histocompatibility complex surface expression by varicella-zoster virus involves open reading frame 66 protein kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Virol. 2007;81(17):9034–9049. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00711-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leen AM, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy with donor T cells prevents and treats adenovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infections after haploidentical and matched unrelated stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;114(19):4283–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith CA, et al. Production of genetically modified Epstein-Barr virus-specific cytotoxic T cells for adoptive transfer to patients at high risk of EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease. J Hematother. 1995;4(2):73–79. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1995.4.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diaz PS, et al. T lymphocyte cytotoxicity with natural varicella-zoster virus infection and after immunization with live attenuated varicella vaccine. J Immunol. 1989;142(2):636–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadzot-Delvaux C, et al. Recognition of the latency-associated immediate early protein IE63 of varicella-zoster virus by human memory T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159(6):2802–2806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishio N, et al. Armed oncolytic virus enhances immune functions of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5195–205. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arvin A, Abendroth A. VZV: immunobiology and host response. 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sen N, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry analysis of human tonsil T cell remodeling by varicella zoster virus. Cell Rep. 2014;8(2):633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eisfeld AJ, et al. Phosphorylation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) major transcriptional regulatory protein IE62 by the VZV open reading frame 66 protein kinase. J Virol. 2006;80(4):1710–1723. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1710-1723.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milikan JC, et al. Identification of viral antigens recognized by ocular infiltrating T cells from patients with varicella zoster virus-induced uveitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(8):3689–3697. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papadopoulou A, et al. Activity of broad-spectrum T cells as treatment for AdV, EBV, CMV, BKV, and HHV6 infections after HSCT. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(242):242ra83. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Long HM, et al. Synthetic Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) Rapidly Induce Exhaustion and Augmented Glycolytic Metabolism In Human T Cells and Implicate Persistent CD28 Signaling As a Driver Of Exhaustion In Human T Cells. Blood. 1912;122:192. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long AH, et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat Med. 2015;21(6):581–90. doi: 10.1038/nm.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stotz SH, et al. T cell receptor (TCR) antagonism without a negative signal: evidence from T cell hybridomas expressing two independent TCRs. J Exp Med. 1999;189(2):253–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leske H, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection of malignant glioma cell cultures: a new candidate for oncolytic virotherapy? Anticancer Res. 2012;32(4):1137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt ML, et al. Favorable prognosis for patients 12 to 18 months of age with stage 4 nonamplified MYCN neuroblastoma: a Children’s Cancer Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6474–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanley PJ, et al. Functionally active virus-specific T cells that target CMV, adenovirus, and EBV can be expanded from naive T-cell populations in cord blood and will target a range of viral epitopes. Blood. 2009;114(9):1958–1967. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Metes D, et al. Ex vivo generation of effective Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes from the peripheral blood of immunocompetent Epstein Barr virus-seronegative individuals. Transplantation. 2000;70(10):1507–15. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200011270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanley PJ, et al. CMV-specific T cells generated from naive T cells recognize atypical epitopes and may be protective in vivo. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(285):285ra63. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markovic SN, et al. A reproducible method for the enumeration of functional (cytokine producing) versus non-functional peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in human peripheral blood. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2006;145(3):438–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.