Summary

Meta-analysis can average estimates of multiple parameters, such as a treatment’s effect on multiple outcomes, across studies. Univariate meta-analysis (UVMA) considers each parameter individually, while multivariate meta-analysis (MVMA) considers the parameters jointly and accounts for the correlation between their estimates. The performance of MVMA and UVMA has been extensively compared in scenarios with two parameters. Our objective is to compare the performance of MVMA and UVMA as the number of parameters, p, increases. Specifically, we show that (i) for fixed-effect meta-analysis, the benefit from using MVMA can substantially increase as p increases; (ii) for random effects meta-analysis, the benefit from MVMA can increase as p increases, but the potential improvement is modest in the presence of high between-study variability and the actual improvement is further reduced by the need to estimate an increasingly large between study covariance matrix; and (iii) when there is little to no between study variability, the loss of efficiency due to choosing random effects MVMA over fixed-effect MVMA increases as p increases. We demonstrate these three features through theory, simulation, and a meta-analysis of risk factors for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Keywords: efficiency, fixed-effect models, multivariate meta-analysis, random effects models

1 Introduction

Multiple studies often target the same scientific question and aim to estimate the same set of parameters. Meta-analyses combine results across studies to obtain a single, more accurate estimate of the desired parameters (Higgins and Green, 2011). When estimating multiple parameters, such as the effect of one treatment on multiple outcomes (Gail et al., 2000; Gleser and Olkin, 2009), the association of multiple treatments or risk factors with a single outcome (Ritz et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2009), or the parameters of a diagnostic test (Rutter and Gatsonis, 2001; Simel and Bossuyt, 2009), the two alternatives are to individually evaluate each parameter through univariate meta-analyses (UVMA) or to perform a single multivariate meta-analysis (MVMA) (Jackson et al., 2011; Riley et al., 2007b; Van Houwelingen et al., 2002). By considering the correlations, MVMA can borrow information across parameters, thus increasing the precision of the summary estimates, as discussed by Riley (2009); Ritz et al. (2008); Riley et al. (2007b) and Riley et al. (2007a).

There are multiple factors that should be considered when deciding between MVMA and UVMA. For example, when the objective is to estimate a function of multiple parameters, MVMA is required for valid statistical inference. Consequently, MVMA should be used in studies comparing the sensitivity and specificity of a new diagnostic test. When studies only estimate subsets of the desired parameters, MVMA can significantly increase precision and reduce reporting bias. However, when studies do not publish within-study correlation matrices, MVMA may be impractical. In settings when both MVMA and UVMA are reasonable approaches, one factor to consider is that MVMA offers a potential gain in efficiency.

While methods for performing MVMA have been introduced and developed within both the fixed (FE) (Berkey et al., 1995, 1996) and random effects (RE) frameworks (Berkey et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2013), the potential gain in efficiency has been repeatedly questioned (Riley et al., 2007a; Bland, 2011; Trikalinos et al., 2013). Much of the recent debate has focused on bivariate RE meta-analysis. Simulations, examples, and theory (Ishak et al., 2007; Riley, 2009; Riley et al., 2007b) all support that MVMA offers minimal benefit in most scenarios and even no benefit when the within-study covariance matrices are the same, as shown by Riley (2009). Comparisons of UVMA and MVMA in the presence of more than two parameters are limited (Berkey et al., 1998; Jackson et al., 2011), but in the available examples, the precision gained from MVMA appears to be slightly stronger. As the number of estimated parameters, p, increases, the potential for borrowing information across parameters increases, and gains from using MVMA should similarly increase. To our knowledge, however, there has been no focused discussion on how MVMA’s gain in efficiency, in either the FE or RE frameworks, changes as the number of parameters, p, increases.

The impetus for this investigation is the growing popularity of meta-analyses in epidemiological studies (Blettner et al., 2014). These studies often estimate a comparatively large number of parameters, such as the odds ratios for a set of related risk factors. Our objective is to provide guidance as to when MVMA may offer significantly more precise estimates of the targeted parameters. In the methods section, we define our metric of comparison to be the relative efficiency and describe the scenarios used to compare UVMA and MVMA. In the results section, we first derive the theoretical relationship between the relative efficiency and number of parameters for key instructive examples. We then use simulations to measure the relative efficiencies for many more complex examples. Finally, we apply these methods to studies from a consortium examining the association between lifestyle risk factors and the risk of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (Morton et al., 2005a,b).

2 Methods

2.1 Notation

Assume that we have I studies. In study i, let μi = (μ1i, …, μpi)′ be a vector of p parameters and let Yi = (Y1i, …, Ypi)′ be a study-specific estimate of those parameters. We assume that, conditional on μi, Yi follows a multivariate normal distribution, Yi|μi ~ MV N(μi, Si), where Si is the within-study covariance matrix. We let and ρkl,i = Cor(Yki, Yli|μki, μli) for study i and parameters k and l. When there are only two parameters or when the correlation is the same for all parameters in the study, we drop the “kl” from the subscript and use ρi.

In the RE framework, we assume that study-specific parameters are random variables following a multivariate normal distribution, μi ~ MV N(μ, Σ), where μ = (μ1, …, μp)′ is the global mean and Σ is the between-study covariance matrix. We let and . In the FE framework, the study-specific parameters are all equal to the global mean, μi ≡ μ, or, equivalently, there is no between study heterogeneity, Σ = 0p×p. The marginal model for study-specific estimates is therefore Yi ~ MV N(μ, Si + Σ), with Si + Σ being the total covariance matrix for study i.

The MVMA estimate of μ is (Raudenbush et al., 1988; Berkey et al., 1995, 1996):

| (1) |

where and estimate the within-study and between-study covariance matrices, respectively. For the RE framework, we estimate the between-study covariance matrix Σ by restricted maximum likelihood (REML), implemented in the mvmeta R package (Gasparrini et al., 2012); other methods have also been proposed (Jackson et al., 2011; Berkey et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2013; Jennrich and Schluchter, 1986; Arends et al., 2003; Ma and Mazumdar, 2011; Mavridis and Salanti, 2013). We do not place any restrictions on the covariance structure in the REML estimation.

The UVMA estimate of μ can be written similarly to Eq. (1), by setting all within-study and between-study correlations to equal 0,

| (2) |

where Ui = diag(Si) and D = diag(Σ). It is easy to see that asymptotically, as the number of subjects per study (FE framework) or as both the number of studies and number of subjects per study (RE framework) increase to infinity, and are unbiased estimates of μ with variances

| (3) |

| (4) |

We define the relative efficiency for , the kth parameter of , to be

and use Eqs. (3) and (4) to calculate the asymptotic relative efficiency for any specified scenario. For evaluating and in RE models, we also discuss the estimates and that would be possible had the true values of Σ and D been known and used in Eqs. (1) and (2). We denote by . The main notation we use is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notation used in the paper.

We let and be, respectively, the UVMA and MVMA estimates produced by Bayesian methods (Wei and Higgins, 2013). For UVMA, we let the prior distributions for μj and be normal (mean=0, variance=1000) and inverse gamma distributions (shape=1/2, scale drawn from inverse of a squared Unif(0,2)), respectively, where j indicates the parameter of interest. For MVMA, we let the prior distributions for μ and Σ be multivariate normal (mean=0p, variance=1000 Ip, where Ip is the p × p diagonal matrix) and inverse Wishart distributions (scale is a p × p identity matrix with entries drawn from the inverse of a squared Unif(0,2), p degrees of freedom), respectively. Bayesian analysis was performed by R and JAGS (Plummer, 2003) using the rjags package. For comparing efficiency, we estimated the variances of and by simulation.

2.2 Preface: two parameters (p=2) and two studies (I=2)

To understand when multivariate modeling has the potential to improve precision, we start by considering the scenario with two parameters (p=2) and two studies (I=2). The univariate and multivariate estimates for the first parameter, μ1, are

| (5) |

| (6) |

where, for the FE case, the weights are estimates of:

where S12,i are the within-study covariances. Note that only MVMA estimates included multiples of estimates of the second parameter, namely Y21 and Y22. The coefficients for Y21 and Y22 in Eq. (6), respectively w21 and −w21, sum to zero. Therefore, including estimates of the second parameter does not influence . The RE case is analogous, but and S12,i are replaced by the sums of the within-study terms and the between-study terms.

For the FE case, for known within-study covariance matrices, the relative efficiency is a function of the correlations, ρ1 and ρ2, and the within-study variances. We will also consider the fractions r1 and r2, of the variances across studies,

| (7) |

In particular, the relative efficiency only depends on the within-study variances through these fractions. In the results section, we study the relationship between the relative efficiency and the four parameters ρ1, ρ2, r1, r2. We emphasize that the subscripts for ρ refer to the study but those for r refer to the parameter.

2.3 Multiple parameters (p ≥ 2)

We compare the efficiency of MVMA and UVMA across a variety of examples. In our first set of examples, we consider studies where the between-study and within-study covariance matrices follow simple patterns. Here, our objective is to understand the conditions that favor MVMA and lower the relative efficiency. In the second set of examples, we consider studies where the covariance matrices are more complex, such as those observed in the InterLymph dataset, which is described in section 2.4. Here, our objective is to understand the potential gain in efficiency for more realistic settings.

We start by comparing MVMA and UVMA for FE meta-analysis. Our first example considers a meta-analysis of two studies, I = 2, where the within-study covariance matrices are exchangeable (compound symmetric). In this example, the asymptotic relative efficiency has a closed form expression, and this form shows how the relationship between the RelEff and the number of parameters depends on r, ρ1, and ρ2, where we can omit the ‘k’ subscript because of symmetry. Our second example, which still assumes within-study covariance matrices are exchangeable, increases the number of studies, letting I = 20, , and ρi = ρ(i − 1)/I, i = 1, …, I. Again, a closed form expression can be used to describe the relationship between RelEff and p. Finally, we consider additional examples where I=20 and the covariance matrices are either AR(1) or block diagonal with blocks of size 5.

We next compare MVMA and UVMA for RE meta-analysis when Σ and D are known. Our first example considers a meta-analysis of twenty studies, I = 20, where both the within-study and between-study covariance matrices are exchangeable, ρBS = 0.5, , and ρi = (i − 1)/I, i = 1, …, I. We use this example to evaluate how the relationship between RelEffT and p depends on σ2/S2. In our second example, where again the within-study covariance matrices are assumed exchangeable, we fix Σ = 0 and evaluate how the relationship depends on I. We note that this example is slightly redundant to the FE example, but will be a needed comparison for discussing the relative efficiency when Σ and D must be estimated. Finally, we consider additional examples where both the within-study and between-study covariance matrices are AR(1) or block diagonal with blocks of size 5. In our next set of examples, we compare MVMA and UVMA for RE meta-analysis when Σ and D are estimated. Values of and were calculated by simulation, described below, with 500 cases and 500 controls.

To understand how UVMA and MVMA are likely to compare in practice, we consider the relative efficiency for RE meta-analyses across a broad range of more complex scenarios. Our aim is to show that the patterns observed in the examples with exchangeable, AR(1), and block diagonal correlation matrices hold more generally. For this demonstration, we randomly generate, using the clusterGeneration R package (Qiu and Joe, 2015), covariance matrices Σ and Si, i ∈ {1, …, I} where each covariance matrix is constructed from eigenvalues randomly generated from Unif(1,10) and eigenvectors corresponding to the columns of randomly generated orthogonal matrices. Therefore, we start by specifying a set of parameters: number of studies (I ∈ {10, 20}); studies either have unequal sample sizes (550, 650, …, 1350, 1450 individuals for I = 10 and 430, 490, …, 1510, 1570 individuals for I = 20) or equal sample sizes (1000 individuals); and , or , with being the average of all within-study variances. Then for each of these 12 sets of parameters and a given p (p ∈ {5, 10, 15, 20}), we randomly generate 5 sets of covariance matrices (both within-study and between-study). For each set of covariance matrices, we then estimate the relative efficiency by the simulations described below. Results from these analyses are presented in the Figs. S6 and S7, with each of the 5 random scenarios corresponding to a different color.

For each example, we evaluated the variance of , and, where applicable, and across 50,000 simulated case/control studies (10,000 for Figs. S6 and S7.) For each simulation, we generate μi ~ MV N(0.2 × 1p, Σ), where 1p is a p-length vector with all entries equal to 1. Σ is either exchangeable, AR(1), block diagonal or a randomly generated positive definite matrix with equal diagonal entries. The vector of p covariates for individual m in populations i is generated as , where 0p is a p-length vector with all entries equal to 0, with Si chosen so that the within-study covariance matrices Si have, for example, and ρi ≈ (i − 1)/I in the exchangeable scenario, or , where S* is a randomly generated correlation matrix, based on an asymptotic approximation in (Agresti, 2014). Case-status is generated as . We generated individuals until we had the number of desired cases and controls in each study.

2.4 Data Example: InterLymph consortium

The International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) includes 17,471 individuals with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) and 23,096 controls from 20 case/control studies conducted in North America, Europe, and Australia and is described by Morton et al. (2005b,a). Their objective was to study the association between lifestyle and environmental factors with the risk of NHL. For purposes of exposition, we focus on the documented association between cigarette smoking and NHL, and between alcohol consumption and NHL (Morton et al., 2005b,a), and use the following variables: the lifetime cigarette exposure in pack-years, the number of servings of wine per week, the number of servings of liquor per week, and the number of servings of beer per week. We used data from the 15 studies, ranging in size from 262 to 3,697 subjects, that contained all four variables and removed individuals with missing values. The study-specific results are presented in Table S1. Variables are highly correlated within studies and these correlations vary considerably across studies (Table S2 and Fig. S1, available as part of the Supporting Information). In each study we modeled the relationship between covariates and NHL using logistic regression. We report meta-analysis of the resulting log(OR ) values.

2.5 InterLymph consortium: simulations

We also compare the performance of MVMA and UVMA on simulated datasets, where the underlying truth reflects our InterLymph results. These simulations, where the within- and between- study correlation matrices are similar to those observed in InterLymph, contrast the exchangeable, AR(1), and block diagonal matrices used in earlier examples. Let us denote the wine, liquour, beer, and smoking variables for individual m in study i by X1,im, X2,im, X3,im, and X4,im, with Xim = (X1,im, X2,im, X3,im, X4,im)′. Let νi and Vi be the estimated mean and covariance for Xi among the controls. Let and be the MVMA estimates of the global mean and between study covariance matrix, respectively. For simulations, we start by defining a set of effects, μsim for each study as either (FE framework) or as a random draw from a normal distribution, N ( ) (RE framework). Then, for each study, we generate a vector (Yim , Xim) for each individual in a large population with Xim ~ N (νi, Vi) and . We then select the same number of individuals for the case/control study as in the original study. We also generated datasets with p = 8 risk factors, with Xim following a normal distribution with mean (νi, νi)′ and covariance matrix:

| (8) |

where , and ρX ∈ {0, 0.5}. For the RE p = 8 scenarios, we considered the between-study covariance matrix:

| (9) |

where 0 is 4 × 4 matrix of zeros.

We considered six scenarios: RE or FE, p = 4 or 8 variables, and, with 8 variables, ρX = 0 or ρX = 0.5. For each scenario, we generated 50,000 simulations. For estimating asymptotic relative efficiencies, we needed the within-study covariance matrices, Si, and estimated them by the empirical covariances matrices of across simulations, after subtracting Σ.

3 Results

3.1 Preface: two parameters, two studies (p=2, I=2)

For a FE meta-analysis, the relative efficiency of UVMA, compared to MVMA, of the first parameter can be described by Result 3.1:

Result 3.1

| (10) |

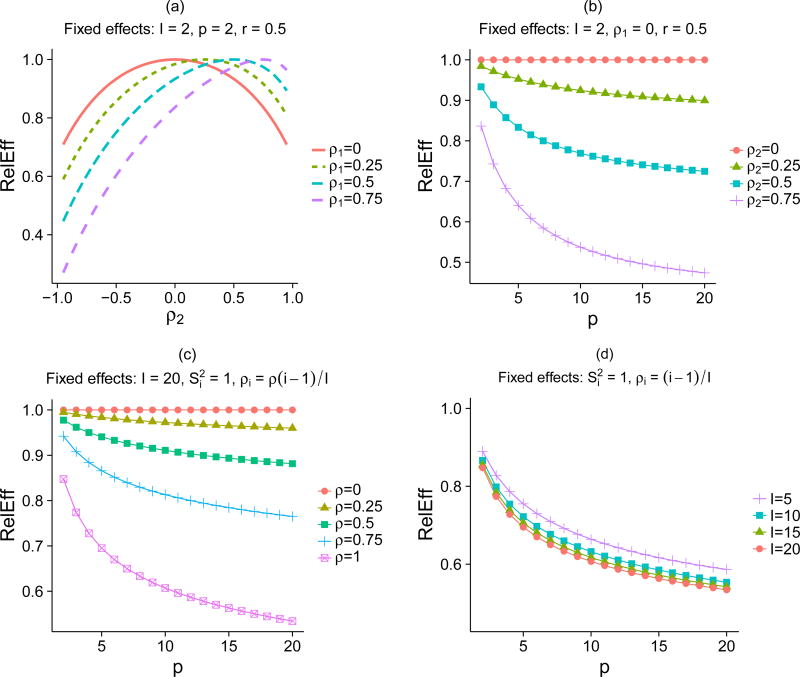

The key observation, which similarly holds for p > 2 and I > 2, is that the UVMA becomes less efficient when there is a large difference in the within-study correlations. In our example (Fig. 1(a)), where r1 = r2 = r , the numerator in Eq. (10) simplifies to r (1 − r )(ρ1 − ρ2)2. The relative efficiency is 1 only when ρ1 − ρ2 = 0 and the relative efficiency decreases as (ρ1 − ρ2)2 increases from 0. The exact gain in efficiency depends on r , with MVMA offering no benefit when r → 0 or r → 1 (Fig. S2(a)).

Fig. 1.

The relative efficiency (RelEff) compares the performance of MVMA and UVMA for FE meta-analysis when the covariance matrix is exchangeable. The RelEff (1) decreases as the difference between the within-study correlations increases (2) decreases as the number of parameters increases and (3) decreases as the number of studies increases. (a) A two-study, two parameter example illustrating (1). (b) A two-study, multi-parameter example illustrating (1) and (2). (c) A twenty-study, multi-parameter example illustrating (1) and (2). (d) A multi-study, multi-parameter example illustrating (1), (2), and (3). The notation includes I: number of studies, p: number of parameters, : within-study variance of an estimated parameter in study i, ρi: within-study correlation between two estimated parameters in study i, and .

In practice, the relative variances, r1 and r2, of the two parameters are often similar because they are both determined by the relative size of the two studies. However, we note that when r1 ≠ r2, the relative efficiency is no longer a strictly increasing function of (ρ1 − ρ2)2 and will no longer equal 1 exactly when ρ1 − ρ2 = 0. Using r1 = 0.5 (Fig. S2(b)) as an example, Eq. (10) shows

Therefore, there are scenarios where MVMA can offer no gain beyond the commonly cited example of equal within-study covariance matrices (Riley et al. , 2007a; Riley, 2009).

3.2 Fixed-effect meta-analysis for multiple parameters (p ≥ 2)

For a FE meta-analysis of multiple parameters (p ≥ 2), we first consider the relative efficiency of UVMA, compared to MVMA, when the within-study covariance matrices are exchangeable. Result 3.2 shows that the relative efficiency decreases as p increases, but approaches a limit well above 0.

Result 3.2

When I = 2, this result simplifies:

| (11) |

We continue with the example where I = 2, r = 0.5, and ρ1 = 0 (Fig. 1(b)). The relative efficiency decreases as p increases, and this decrease, per additional parameter, is larger when p is small. When ρ2 = 0.75, the relative efficiency drops from 0.84 to 0.68 as p increases from 2 to 4, whereas it only drops from 0.52 to 0.50 as p increases from 12 to 14. In our example with I = 20 (Fig. 1(c)) the relative efficiency shows a similar trend as p increases. In both of these examples, the relative efficiency increases towards 1 as the range of correlations shrinks towards 0. Another feature is that the RelEff increases slightly as the number of studies decreases from I = 20 to I = 5 (Fig. 1(d)), suggesting the benefit of MVMA is greater in meta-analyses containing larger numbers of studies. We next consider the I=20 examples when the covariance matrices follow an AR(1) and block diagonal structure. In these examples (Fig. S3), which are more likely to represent real-world data, we find that relative efficiency does not decrease as strongly with the number of parameters. In the example with the block diagonal covariance matrix, the relative efficiency clearly reaches its minimum when p=5, the size of the blocks.

3.3 Random effects meta-analysis for multiple parameters (p ≥ 2)

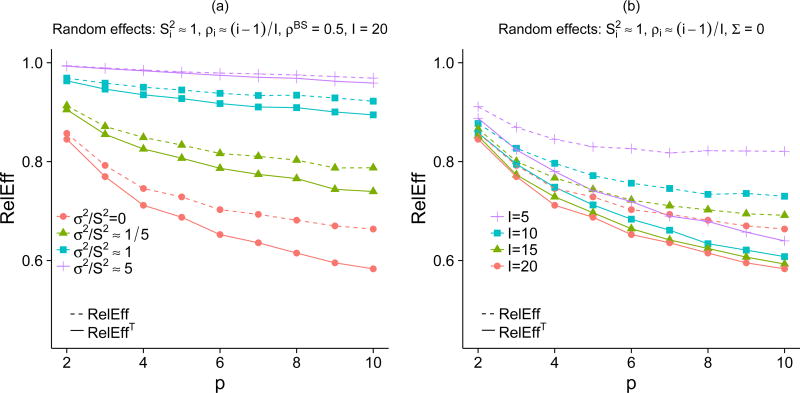

The benefit of MVMA tends to be smaller, or the relative efficiency tends to be larger, when performing RE meta-analysis. We first present the scenario where Σ is known, thus looking at RelEffT. We again start by considering an example where the covariance matrices are exchangeable, I = 20, ρi ≈ (i − 1)/I , and (solid lines in Fig. 2(a)). We show that the relative efficiency increases as the ratio of the between-study and within-study variances increases. As a point of reference, we note that solid orange line (RelEffT) in Fig. 2(a) is nearly identical to the solid orange line in Fig. 1(d), the slight difference being due to the data generation mechanism and the estimation of within-study covariance matrices. When comparing this FE scenario (σ2 = 0) to the scenario where the within- and between- study variances are equal (σ2/S2 = 1), the RelEffT increases from 0.73 to 0.95 for p = 4. Because all studies share a common between-study covariance matrix, the covariance matrices of Yi become increasingly similar as σ2 increases, thereby lowering the potential benefit of MVMA. Fig. 2(a) emphasizes that there is little to be gained by using MVMA when the between-study variance is comparatively large (σ2/S2 = 5.)

Fig. 2.

The relative efficiency when the between-study covariance matrices are known (RelEffT) and when the between-study covariance matrices are unknown (RelEff) compares the performance of MVMA and UVMA for RE meta-analyses when the covariance matrices are exchangeable. Properties of RelEffT and RelEff include (1) RelEffT is less than RelEff (2) RelEffT and RelEff both decrease as the number of parameters increases (3) RelEffT and RelEff both decrease as the between-study variance decreases (4) the difference between RelEffT and RelEff decreases as the number of studies increases. (a) A twenty-study, multi-parameter example illustrating (1), (2), and (3). (b) A multi-study, multi-parameter example illustrating (1), (2), and (4). The notation includes I: number of studies, p: number of parameters, : within-study variance of an estimated parameter in study i, σ2: between-study variance of a single parameter, Σ: between-study covariance matrix, ρi: within-study correlation between two estimated parameters in study i, ρBS: between-study correlation between two parameters.

We next considered the relative efficiency when the covariance matrices are AR(1) and block diagonal. Similar to our observations when using FE meta-analysis, the benefit from MVMA did not increase as rapidly with the number of parameters (Figs. S4 and S5). Moreover, the effects of changing either the number of studies or the ratio (σ2/S2) were similar to those observed in the comparable examples with an exchangeable correlation matrix. Finally, when we considered the examples where the covariance matrices were randomly generated (Figs. S6 and S7), we found the benefit of MVMA to be the smallest, with the RelEffT > 0.94 when .

3.4 Estimating Σ for multiple parameters (p ≥ 2)

In the previous examples, Σ and D were assumed known. Here, we consider the RelEff when using their estimates, and . We must estimate more parameters for MVMA, and therefore the relative efficiency of the UVMA is expected to increase. Figs. 2(a) and 2(b) show that despite estimating more parameters, estimates from MVMA still have lower variance than their counterparts from UVMA. We return to the example where the covariance matrices are exchangeable, I = 20, ρi ≈ (i − 1)/I , and . In Fig. 2(a), we see the loss of efficiency is relatively low when I = 20, regardless of the σ2/S2 ratio. We next consider the effect of decreasing the number of studies. Fig. 2(b) shows that as the number of studies decreases the loss in efficiency from having to estimate the covariance matrices increases. For completeness, we note that the loss in efficiency from having to estimate the covariance matrices in the Σ = 0 example (Fig. 2(b)) shows the cost from using a RE meta-analysis when the assumptions for a FE meta-analysis hold true. The potential cost from not using a FE meta-analysis, when applicable, therefore increases with p . When the correlation matrices are AR(1) and block diagonal (Figs. S4 and S5) and when the within-study covariance matrices are randomly generated (Figs. S6 and S7), similar trends are observed.

We next evaluated MVMA’s gain in efficiency when using Bayesian methods. In general, the relative efficiencies, RelEffB, observed for the Bayesian methods were similar to those observed when using RE meta-analysis with unknown covariance matrices. For the examples with the exchangeable, AR(1), and block diagonal covariance matrices, Figs. S4, S5, and S8 show the similarities between RelEffB and RelEff. However, we note that when the number of studies is small (I=5), RelEffB tends to be smaller than RelEff, indicating that MVMA may be slightly more important for Bayesian methods. For completeness, we also compared the performance of the Bayesian and frequentist MVMA estimates of μ. Across all examples (Figs. S4, S5, and S8), the two methods performed similarly, except we found that the variance of the Bayesian estimates tended to be slightly smaller when there were few studies (I=5).

3.5 InterLymph consortium: simulations

We simulated datasets similar to that collected by InterLymph as described in section 2.5. Comparisons between MVMA and UVMA are presented in Table 2. Each simulation included 18,091 individuals from 15 case/control studies, and focused on either p = 4 or 8 variables. We first considered the scenario where both the truth and chosen analysis are within the FE framework. Again, our theory-based estimates of relative efficiency predicted by Eqs. (3) and (4), are similar to those observed empirically. Therefore, when the number of parameters is large (p=8) and there is non-neglible correlation across multiple variables (ρX = 0.5), MVMA estimates may offer significant improvements in efficiency. When the true model is a FE model and the chosen analysis is RE, then the ratio of variances, , is closer to 1 than either what is predicted by theory or obtainable when using a FE analysis. The loss of efficiency of the RE MVMA compared to FE MVMA when there was no between study heterogeneity was 25.6%, 19.5%, 9.6%, and 6.8% for , , , and when p = 4, and 31.6%, 22.9%, 17.0%, and 10.2% when p = 8 and ρX = 0.5, respectively. When both the true model and chosen analysis are within the RE framework, then the theory suggests MVMA should offer significant improvement, reducing the variance of the estimates by ≥ 10% in most of the examples from Table 2. However, in practice, the gain in efficiency was not as large as predicted by theory.

Table 2.

The asymptotic and empirical relative efficiencies from the InterLymph simulations. Simulations either assumed μi was constant across studies (FE) or normally distributed (RE), included either 4 or 8 parameters, and let the two sets of four variables be independent (ρX = 0) or dependent (ρX = 0.5). Both the asymptotic/expected relative efficiencies and empirical/observed relative efficiencies are provided from FE and RE meta-analysis. Further details on the simulation framework are in Section 2.5.

| FE analysis | RE analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truth | Number of coefficients (p) |

ρX | Parameter | Asymptotic RelEff |

Empirical RelEff |

Asymptotic RelEffT |

Empirical RelEff |

| FE | p = 4 | μ1 | 0.854 | 0.841 | 0.854 | 0.958 | |

| μ2 | 0.845 | 0.838 | 0.845 | 0.912 | |||

| μ3 | 0.963 | 0.952 | 0.963 | 0.995 | |||

| μ4 | 0.985 | 0.974 | 0.985 | 1.003 | |||

|

| |||||||

| p = 8 | ρX = 0 | μ1 | 0.853 | 0.830 | 0.853 | 1.100 | |

| μ2 | 0.842 | 0.818 | 0.842 | 0.957 | |||

| μ3 | 0.962 | 0.938 | 0.962 | 1.048 | |||

| μ4 | 0.984 | 0.958 | 0.984 | 1.013 | |||

|

| |||||||

| p = 8 | ρX = 0.5 | μ1 | 0.587 | 0.572 | 0.587 | 0.698 | |

| μ2 | 0.802 | 0.784 | 0.802 | 0.896 | |||

| μ3 | 0.844 | 0.821 | 0.844 | 0.911 | |||

| μ4 | 0.795 | 0.775 | 0.795 | 0.820 | |||

|

| |||||||

| RE | p = 4 | μ1 | 0.889 | 1.045 | |||

| μ2 | 0.897 | 0.926 | |||||

| μ3 | 0.911 | 0.954 | |||||

| μ4 | 0.977 | 0.977 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| p = 8 | ρX = 0 | μ1 | 0.890 | 1.152 | |||

| μ2 | 0.898 | 0.951 | |||||

| μ3 | 0.911 | 0.972 | |||||

| μ4 | 0.978 | 0.975 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| p = 8 | ρX = 0.5 | μ1 | 0.679 | 0.857 | |||

| μ2 | 0.873 | 0.926 | |||||

| μ3 | 0.848 | 0.924 | |||||

| μ4 | 0.813 | 0.837 | |||||

3.6 InterLymph consortium: Data Analysis

We evaluated the associations between the risk of NHL and two behaviors, alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking, in the InterLymph consortium. Results are presented in Table 3. Similar to results from previous findings, we observed that alcohol consumption reduces the risk of NHL, while smoking increases the risk of NHL. Using the FE MVMA, an additional serving of wine, liquor, or beer per day equated to an OR of 0.98 (0.95–1.00), 0.98 (0.91–1.05), and 0.94 (0.91–0.98) respectively. For smoking, 60 pack-years equated to an OR of 1.21 (1.11–1.32) compared to never smokers. The results from all four analyses (MVMA or UVMA, FE or RE) are qualitatively similar. Wine, beer, and smoking showed statistically significant effects regardless of analysis, with the caveat that the p-value for wine in the FE meta-analysis was 0.056. For the FE framework, we observed tighter confidence intervals for the wine and liquor variables from the MVMA, compared to UVMA, as expected based on the lower relative efficiencies observed in our simulations (Table 2). For the RE framework, we also observed slightly tighter confidence intervals for MVMA, but as expected, the magnitude of the reduction is reduced. We also confirmed the well known observation that confidence intervals from RE meta-analysis are larger than those from FE meta-analysis, regardless of whether using MVMA or UVMA.

Table 3.

Estimates of log ORs (95% confidence intervals) for lifestyle risk factors from the InterLymph consortium. Four estimates are provided for each log(OR). Multivariate (MVMA) and univariate (UVMA) estimates are provided for FE and RE effects meta-analysis. The wine, liquor, and beer variables are measured in servings per week/100, the smoking variable is measured in pack-years/100.

| FE analysis | RE analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | MVMA | UVMA | MVMA | UVMA |

| Wine | −0.33 (−0.67, 0.01) | −0.49 (−0.86, −0.12) | −0.59 (−1.01, −0.18) | −0.49 (−0.86, −0.12) |

| Liquor | −0.31 (−1.31, 0.69) | −0.18 (−1.26, 0.90) | 0.06 (−1.56, 1.68) | 0.26 (−1.39, 1.92) |

| Beer | −0.82 (−1.38, −0.27) | −0.96 (−1.53, −0.40) | −0.75 (−1.48, −0.01) | −0.92 (−1.75, −0.09) |

| Smoking | 0.32 (0.17, 0.46) | 0.32 (0.18, 0.47) | 0.26 (0.06, 0.47) | 0.26 (0.06, 0.46) |

4 Discussion

Numerous studies, using simulation (Riley, 2009), theory (Riley et al. , 2007a; Riley, 2009), and examples (Jackson et al. , 2011; Ma and Mazumdar, 2011; Riley et al. , 2007a; Trikalinos et al. , 2013), have compared the efficiency of multivariate and univariate meta-analyses. Here, we expand the discussion by systematically exploring the relative efficiency of the two methods as the number of parameters p increases. For FE meta-analysis, we show that the benefit from using MVMA can significantly increase as p increases for diverse covariance structures among studies. For RE meta-analysis, we show that, theoretically, the benefit from MVMA can also significantly increase with p , but in practice, the benefits may be reduced by the need to estimate the between-study correlation matrix. Because the benefit of MVMA is far stronger in FE meta-analysis, choosing to use RE meta-analysis when p is large and there is no or little heterogeneity can come at a surprisingly large cost to efficiency.

Our conclusion is that there is likely to be only a minimal gain of efficiency, when substituting MVMA for UVMA, in many RE meta-analyses with p > 2. This conclusion agrees with the literature focused on the meta-analysis of two parameters (Riley et al. , 2007a; Riley, 2009) and a recent comparison of the two methods on 45 meta-analyses studying a categorical outcome (Trikalinos et al. , 2013). MVMA only offered significant gains in efficiency when using FE meta-analysis and when the estimates of all parameters were highly correlated. However, it is worth highlighting that those study characteristics that affect the relative efficiency of MVMA and UVMA estimates in the p = 2 scenario remain important for larger p . The improvement offered by MVMA is larger when the correlation structures vary greatly across studies and when the true study-specific parameters are similar across studies. In our data analysis, we focused on smoking and alcohol variables which do show a broad range of correlation structures. However, even in this targeted example, the gain in efficiency from using MVMA was minimal in RE meta-analysis.

This work is not meant to be a comprehensive comparison of MVMA and UVMA. We do not address issues such as when studies estimate different sets of parameters (Jackson et al. , 2011), publish only the most favorable results (Kirkham et al. , 2012), have covariates that can be modeled in a meta-regression (Berkey et al. , 1998; Jackson et al. , 2013), or are intended to estimate functions of multiple parameters (Riley et al. , 2007a). Furthermore, we assume that sample sizes are large enough so that estimated parameters follow an approximately normal distribution (Hamza et al. , 2008; Stijnen et al. , 2010; Trikalinos et al. , 2013; Böhning et al. , 2015) and that all within-study covariance matrices are available to the investigator (Ishak et al. , 2007; Riley et al. , 2008; Riley, 2009). Finally, we did not study other approaches such as methods that enforce structure on the between-study covariance matrix (Gasparrini and Armstrong, 2011).

In general, the choice of whether or not to use MVMA will depend on the specific objectives of the meta-analysis, the characteristics of the included studies, and the implicit cost of obtaining all within-study covariance matrices. In our discussed examples, we found that MVMA was most beneficial when using a FE meta-analysis and when the estimates of all parameters were highly correlated. When using RE meta-analysis, we found that the need to estimate the between-study covariance matrix limited the observed gain in efficiency. When only small groups of covariates were highly correlated, such as in our simulations where the within-study covariance matrices were either block-diagonal or AR(1), we found that the gain in efficiency was again limited. Similarly limited gains were observed in the InterLymph examples and when we randomly generated covariance matrices. In choosing the appropriate analysis, the potential gain in efficiency would be weighed against the various costs of the more complicated analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph) for generously sharing their data. Detailed acknowledgements are included in the Supporting Information file. We also thank the editor, associate editor, and reviewer, whose constructive comments helped greatly improve the manuscript. This study utilized the computational resources of the Biowulf system at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (http://biowulf.nih.gov).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Arends LR, Vokó Z, Stijnen T. Combining multiple outcome measures in a meta-analysis: an application. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:1335–1353. doi: 10.1002/sim.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkey C, Anderson J, Hoaglin D. Multiple-outcome meta-analysis of clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;15:537–557. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960315)15:5<537::AID-SIM176>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkey C, Antczak-Bouckoms A, Hoaglin D, Mosteller E, Pihlstrom B. Multiple-outcomes meta-analysis of treatments for periodontal disease. Journal of Dental Research. 1995;74:1030–1039. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkey C, Hoaglin D, Antczak-Bouckoms A, Mosteller F, Colditz G. Meta-analysis of multiple outcomes by regression with random effects. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:2537–2550. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981130)17:22<2537::aid-sim953>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland JM. Comments on ‘Multivariate meta-analysis: Potential and promise’ by Jackson et al., Statistics in Medicine. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30:2502–2503. doi: 10.1002/sim.4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blettner M, Krahn U, Schlattmann P. Meta-analysis in epidemiology. Handbook of Epidemiology. 2014:1377–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Böhning D, Mylona K, Kimber A. Meta-analysis of clinical trials with rare events. Biometrical Journal. 2015;57:633–648. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201400184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Manning AK, Dupuis J. A Method of Moments Estimator for Random Effect Multivariate Meta-Analysis. Biometrics. 2012;68:1278–1284. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2012.01761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gail MH, Pfeiffer R, Van Houwelingen HC, Carroll RJ. On meta-analytic assessment of surrogate outcomes. Biostatistics. 2000;1:231–246. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini A, Armstrong B. Multivariate meta-analysis: A method to summarize non-linear associations. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30:2504–2506. doi: 10.1002/sim.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, Kenward MG. Multivariate meta-analysis for non-linear and other multi-parameter associations. Statistics in Medicine. 2012;31:3821–3839. doi: 10.1002/sim.5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleser LJ, Olkin I. Stochastically dependent effect sizes. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2009:357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza TH, van Houwelingen HC, Stijnen T. The binomial distribution of meta-analysis was preferred to model within-study variability. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2008;61:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; Oxford: 2011. URL http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ishak KJ, Platt RW, Joseph L, Hanley JA. Impact of approximating or ignoring within-study covariances in multivariate meta-analyses. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;27:670–686. doi: 10.1002/sim.2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, Riley R, White IR. Multivariate meta-analysis: Potential and promise. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30:2481–2498. doi: 10.1002/sim.4172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, White I, Kostis J, Wilson A, Folsom A, et al. Systematically missing confounders in individual participant data meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. Statistics in Medicine. 2009;28:1218–1237. doi: 10.1002/sim.3540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, White IR, Riley RD. A matrix-based method of moments for fitting the multivariate random effects model for meta-analysis and meta-regression. Biometrical Journal. 2013 doi: 10.1002/bimj.201200152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D, White IR, Thompson SG. Extending DerSimonian and Laird’s methodology to perform multivariate random effects meta-analyses. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29:1282–1297. doi: 10.1002/sim.3602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennrich RI, Schluchter MD. Unbalanced repeated-measures models with structured covariance matrices. Biometrics. 1986:805–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham JJ, Riley RD, Williamson PR. A multivariate meta-analysis approach for reducing the impact of outcome reporting bias in systematic reviews. Statistics in medicine. 2012;31:2179–2195. doi: 10.1002/sim.5356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Mazumdar M. Multivariate meta-analysis: a robust approach based on the theory of U-statistic. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30:2911–2929. doi: 10.1002/sim.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavridis D, Salanti G. A practical introduction to multivariate meta-analysis. Statistical methods in medical research. 2013;22:133–158. doi: 10.1177/0962280211432219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton LM, Hartge P, Holford TR, Holly EA, Chiu BC, et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (interlymph) Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2005a;14:925–933. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton LM, Zheng T, Holford TR, Holly EA, Chiu BC, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a pooled analysis. Lancet Oncology. 2005b;6:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M. Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on distributed statistical computing. Vol. 124. Vienna: 2003. JAGS: A program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu W, Joe H. clusterGeneration: Random Cluster Generation (with Specified Degree of Separation) 2015 URL http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=clusterGeneration, R package version 1.3.4.

- Raudenbush SW, Becker BJ, Kalaian H. Modeling multivariate effect sizes. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:111. [Google Scholar]

- Riley RD. Multivariate meta-analysis: the effect of ignoring within-study correlation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2009;172:789–811. [Google Scholar]

- Riley RD, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, Sutton AJ, Thompson JR. An evaluation of bivariate random-effects meta-analysis for the joint synthesis of two correlated outcomes. Statistics in Medicine. 2007a;26:78–97. doi: 10.1002/sim.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RD, Abrams KR, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC, Thompson JR. Bivariate random-effects meta-analysis and the estimation of between-study correlation. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2007b;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley RD, Thompson JR, Abrams KR. An alternative model for bivariate random-effects meta-analysis when the within-study correlations are unknown. Biostatistics. 2008;9:172–186. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxm023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz J, Demidenko E, Spiegelman D. Multivariate meta-analysis for data consortia, individual patient meta-analysis, and pooling projects. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference. 2008;138:1919–1933. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Statistics in Medicine. 2001;20:2865–2884. doi: 10.1002/sim.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simel DL, Bossuyt PM. Differences between univariate and bivariate models for summarizing diagnostic accuracy may not be large. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62:1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stijnen T, Hamza TH, Özdemir P. Random effects meta-analysis of event outcome in the framework of the generalized linear mixed model with applications in sparse data. Statistics in medicine. 2010;29:3046–3067. doi: 10.1002/sim.4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trikalinos TA, Hoaglin DC, Schmid CH. An empirical comparison of univariate and multivariate meta-analyses for categorical outcomes. Statistics in Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1002/sim.6044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:589–624. doi: 10.1002/sim.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Higgins J. Bayesian multivariate meta-analysis with multiple outcomes. Statistics in Medicine. 2013;32:2911–2934. doi: 10.1002/sim.5745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.