Abstract

Background

Epidural analgesia for pain relief in labour prolongs the second stage of labour and results in more instrumental deliveries. It has been suggested that a more upright position of the mother during all or part of the second stage may counteract these adverse effects. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2013.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different birthing positions (upright and recumbent) during the second stage of labour, on important maternal and fetal outcomes for women with epidural analgesia.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth's Trials Register (19 September 2016) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

All randomised or quasi‐randomised trials including pregnant women (either primigravidae or multigravidae) in the second stage of induced or spontaneous labour receiving epidural analgesia of any kind. Cluster‐RCTs would have been eligible for inclusion in this review but none were identified. Studies published in abstract form only were eligible for inclusion.

We assumed the experimental type of intervention to be the maternal use of any upright position during the second stage of labour, compared with the control intervention of the use of any recumbent position.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion, assessed risk of bias, and extracted data. Data were checked for accuracy. We contacted study authors to try to obtain missing data.

Main results

Five randomised controlled trials, involving 879 women, comparing upright positions versus recumbent positions were included in this updated review. Four trials were conducted in the UK and one in France. Three of the five trials were funded by the hospital departments in which the trials were carried out. For the other three trials, funding sources were either unclear (one trial) or not reported (two trials). Each trial varied in levels of bias. We assessed all the trials as being at low or unclear risk of selection bias. None of the trials blinded women, staff or outcome assessors. One trial was poor quality, being at high risk of attrition and reporting bias. We assessed the evidence using the GRADE approach; the evidence for most outcomes was assessed as being very low quality, and evidence for one outcome was judged as moderate quality.

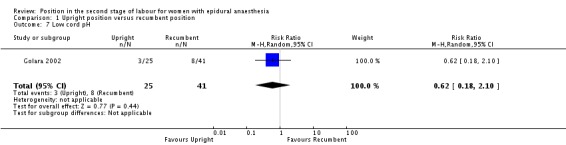

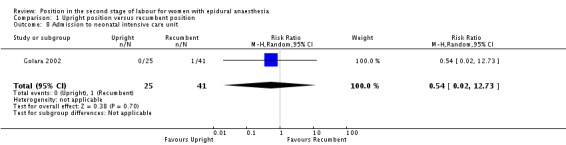

Overall, we identified no clear difference between upright and recumbent positions on our primary outcomes of operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal) (average risk ratio (RR) 0.97; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 to 1.29; five trials, 874 women; I² = 54% moderate‐quality evidence), or duration of the second stage of labour measured as the randomisation‐to‐birth interval (average mean difference ‐22.98 minutes; 95% CI ‐99.09 to 53.13; two trials, 322 women; I² = 92%; very low‐quality evidence). Nor did we identify any clear differences in any other important maternal or fetal outcome, including trauma to the birth canal requiring suturing (average RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.37; two trials; 173 women; studies = two; I² = 74%; very low‐quality evidence), abnormal fetal heart patterns requiring intervention (RR 1.69; 95% CI 0.32 to 8.84; one trial; 107 women; very low‐quality evidence), low cord pH (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.18 to 2.10; one trial; 66 infants; very low‐quality evidence) or admission to neonatal intensive care unit (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.02 to 12.73; one trial; 66 infants; very low‐quality evidence). However, the CIs around each estimate were wide, and clinically important effects have not been ruled out. Outcomes were downgraded for study design, high heterogeneity and imprecision in effect estimates.

There were no data reported on blood loss (greater than 500 mL), prolonged second stage or maternal experience and satisfaction with labour. Similarly, there were no analysable data on Apgar scores, and no data reported on the need for ventilation or for perinatal death.

Authors' conclusions

There are insufficient data to say anything conclusive about the effect of position for the second stage of labour for women with epidural analgesia. The GRADE quality assessment of the evidence in this review ranged between moderate to low quality, with downgrading decisions based on design limitations in the studies, inconsistency, and imprecision of effect estimates.

Women with an epidural should be encouraged to use whatever position they find comfortable in the second stage of labour.

More studies with larger sample sizes will need to be conducted in order for solid conclusions to be made about the effect of position on labour in women with an epidural. Two studies are ongoing and we will incorporate the results into this review at a future update.

Future studies should have the protocol registered, so that sample size, primary outcome, analysis plan, etc. are all clearly prespecified. The time or randomisation should be recorded, since this is the only unbiased starting time point from which the effect of position on duration of labour can be estimated. Future studies might wish to include an arm in which women were allowed to choose the position in which they felt most comfortable. Future studies should ensure that both compared positions are acceptable to women, that women can remain in them for most of the late part of labour, and report the number of women who spend time in the allocated position and the amount of time they spend in this or other positions.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Analgesia, Epidural; Analgesia, Epidural/methods; Analgesia, Obstetrical; Analgesia, Obstetrical/methods; Cesarean Section; Cesarean Section/statistics & numerical data; Extraction, Obstetrical; Extraction, Obstetrical/methods; Labor Stage, Second; Labor Stage, Second/physiology; Patient Positioning; Patient Positioning/methods; Posture; Posture/physiology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Upright or recumbent positions in late labour for women using an epidural for pain relief in labour

What is the issue?

We want to find out whether different birthing positions (upright or lying down) during the second stage of labour for women with epidurals affect outcomes for the women and babies. For the women this includes whether they need a caesarean section, instrumental birth or need suturing following tears to the perineum, and for the babies, whether they cope well with labour or need admission to special care baby unit. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2013.

Why is this important?

An epidural is the most effective method for pain relief during labour. It is often used by women even though it can make labour longer and increase the need for forceps and ventouse (vacuum) birth. Instrumental deliveries are associated with the possibility of the woman developing prolapse, urinary incontinence, or painful sexual intercourse. Low‐dose epidural techniques, also known as 'walking' epidurals, mean that women can still be mobile during their labour. Some experts have suggested that taking an upright position in late labour (such as standing, sitting, squatting) will reduce these negative effects of an epidural.

What evidence did we find?

We searched for evidence in September 2016. No new studies were included in this updated review as a result of the updated search.

Five randomised controlled trials, involving 879 women, comparing upright positions versus recumbent (lying down) positions were already included in the review. Four trials took place in the UK and one was conducted in France. Three of the five trials were funded by the hospital departments in which the trials were carried out. Funding sources for the other trials were either unclear (one trial) or not reported (two trials). All the trials were assessed as being at low or unclear risk of selection bias. None of the trials blinded women, staff or outcome assessors. The methodological quality of one trial was poor.

Overall, upright or recumbent position made no difference to which women had an operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal) (moderate‐quality evidence), or how long they had to push before the baby was born (very low‐quality evidence). We did not find any clear differences in any other important maternal or fetal outcomes, including tears which needed suturing (very low‐quality evidence), instrumental births due to abnormal heart patterns of the unborn baby (very low‐quality evidence), too much acid in the cord blood (very low‐quality evidence) or babies needing admission to neonatal intensive care unit (very low‐quality evidence). However, due to the nature of the results, clinically important effects have not been ruled out.

There were no data reported on blood loss (greater than 500 mL), very long second stage or the women's experiences and satisfaction with labour. Similarly, there were no useful data on Apgar scores, and no data reported on babies dying or needing help to breathe.

What does this mean?

The five randomised controlled trials (involving 879 women) evaluated in this review do not show a clear effect of any upright position compared with a lying down position. The trials are small however, and cannot rule out any small important benefits or harms, so women should be encouraged to take up the position they prefer. More evidence is needed (two studies are ongoing and will be incorporated into this review in a subsequent update). Future, high‐quality trials should involve larger numbers of women and ensure that the positions under study are acceptable to women.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Upright position compared to recumbent position for the second stage of labour for women with epidural anaesthesia

| Upright position compared to recumbent position for the second stage of labour for women with epidural anaesthesia | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with epidural anaesthesia in the second stage of labour Setting: hospitals in France (1 study) and the UK (4 studies) Intervention: upright position Comparison: recumbent position | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with recumbent position | Risk with upright position | |||||

| Operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal) | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.76 to 1.25) | 874 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1,2 | ||

| 464 per 1000 | 450 per 1000 (352 to 579) | |||||

| Duration of second stage labour (minutes) (from time of randomisation to birth) | The mean duration of second stage labour was 22.98 minutes less for women in the upright position (99.09 minutes less to 53.13 minutes more) | 322 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low3,4 | |||

| Trauma to birth canal requiring suturing | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.66 to 1.37) | 173 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low4,5,6 | ||

| 800 per 1000 | 760 per 1000 (528 to 1000) | |||||

| Blood loss (greater than 500 mL) (or as defined by trial authors) | Study population | ‐ | (0 studies) | ‐ | No trial reported this outcome | |

| see comment | see comment | |||||

| Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, requiring intervention | Study population | RR 1.69 (0.32 to 8.84) | 107 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low7,8 | ||

| 41 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (13 to 361) | |||||

| Low cord pH less than 7.1 (or as defined by trial authors) | Study population | RR 0.61 (0.18 to 2.10) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low7,8 | ||

| 195 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (35 to 410) | |||||

| Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | Study population | RR 0.54 (0.02 to 12.73) | 66 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low7,8 | ||

| 24 per 1000 | 13 per 1000 (0 to 310) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1All studies had design limitations. One trial contributing 24.2% weight had serious design limitations (‐1). 2Heterogeneity, I2 = 54% (not downgraded). 3Severe heterogeneity, I2 = 92% (‐1). 4Small sample size and very wide confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect (‐2). 5Both studies contributing data had design limitations (‐1). 6High heterogeneity, I2 = 74% (‐1). 7One study with design limitations. (‐1). 8Very small sample size, few events and wide confidence intervals that cross the line of no effect (‐2).

Background

Description of the condition

Epidural analgesia is commonly used as a form of pain relief in labour. Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have found that it is more effective than other non‐epidural methods (Anim‐Somuah 2005). However, epidurals result in a longer second stage of labour and more instrumental deliveries (Anim‐Somuah 2005). This matters because prolonged second stage of labour may increase the risk of fetal respiratory acidosis and postpartum haemorrhage (Watson 1994). Instrumental deliveries are associated with prolapse, urinary incontinence, and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) (Liebling 2004; MacLennan 2000). A survey during 2005 and 2006 showed that 22% of all deliveries in UK National Health Service (NHS) hospitals involve an epidural (Richardson 2007); in other countries, for example, Canada, epidural rates may be even higher. This is why strategies to shorten the second stage of labour and reduce instrumental deliveries in this setting are important.

There are several proposed mechanisms for the association between epidurals and increased instrumental deliveries. Epidurals increase the risk of malposition of the fetal head, in particular the fetal occiput‐posterior position, a key factor in instrumental birth and prolonged labour (Lieberman 2005; Martino 2007). Secondly, epidurals may interfere with the release of oxytocin as the pelvic floor stretches in the late second stage of labour (Goodfellow 1983; Rahm 2002). Finally, epidurals may inhibit the mother's bearing down reflex at the same time.

Description of the intervention

With the advancement of low‐dose epidural techniques, also known as 'walking' epidurals, women with an epidural are now being provided with the opportunity to remain mobile during their labour, and to adopt some upright positions such as standing and ambulation which may not be possible for women with a traditional epidural (COMET 2001). The use of ambulation during labour has been associated with more efficient uterine action, labours of a shorter duration, and aiding the descent of the fetal head through encouraging the effects of gravity (COMET 2001; Flynn 1978). The use of low‐dose epidurals is also thought to aid the maternal efforts required to give birth through the preservation of motor function (COMET 2001). The increased number of vaginal deliveries seen with this form of analgesia is thought to be due to the ability of the women to adopt an upright position during labour (COMET 2001).

How the intervention might work

One suggestion to reduce adverse outcomes in labour with an epidural is the use of alternative maternal birth positions. Although it has become more common in the West to deliver in the supine position, this position may result in a higher number of instrumental deliveries and episiotomies (De Jonge 2004). In women without an epidural, a number of observational studies have suggested that delivering in an upright position results in shorter labours, lower incidence of instrumental deliveries and episiotomies, and is a more comfortable birth position (Bodner‐Adler 2003; Mendez‐Bauer 1975). Some small RCTs (for example, Chen 1987) and two systematic reviews (De Jonge 2004; Gupta 2004) have confirmed this. It has been proposed that these benefits are due to a higher resting intrauterine pressure which contributes to the downward birth force and the bearing‐down forces (Chen 1987), as well as contractions of a greater intensity (Mendez‐Bauer 1975).

Another possible way to facilitate spontaneous birth would be positions that take the body weight off the sacrum and allow the pelvic outlet to expand. Although it would be possible to classify positions into 'weight on' and 'weight off' the sacrum, and examine trials that compared such positions, this has not been done in the present review.

Why it is important to do this review

Although a Cochrane Review (Gupta 2012) has assessed the use of upright positions in the second stage of labour, it did not include women with epidurals, and therefore the findings can not be generalised. The benefits noted in women without an epidural may potentially offset some of the effect an epidural may have on prolongation of labour, and highlights the importance of carrying out this systematic review. The present review will test the effect of vertical versus horizontal positions in women with all types of epidural. We recognise that some vertical positions, such as ambulation, standing and squatting, as well as some horizontal positions, such as knee chest, may be difficult for women with a traditional epidural to maintain. However, other vertical positions, for example, sitting supported, are possible even with a traditional epidural, so we have included traditional epidurals in the analysis.

A recent non‐Cochrane review (Roberts 2005) attempted just this; however, it was unable to report any data for the fetal outcomes because the trials did not make this information available. Therefore, it is our aim to apply the more stringent Cochrane approach, which would involve contacting study authors where data are missing, in evaluating this much disputed aspect of obstetrics.

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2013 (Kemp 2013).

Objectives

To assess the effects of different birthing positions (upright and recumbent) during the second stage of labour, on important maternal and fetal outcomes for women with epidural analgesia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised or quasi‐randomised trials. Cluster‐RCTs would have been eligible for inclusion in this review but none were identified. Studies published in abstract form only were eligible for inclusion. Where further information was required, we planned to contact the authors of relevant studies.

Types of participants

All pregnant women (primigravidae and multigravidae) in the second stage of induced or spontaneous labour receiving epidural analgesia. We included women with any type of epidural. We included women recruited and randomised in any stage of labour. We only included singleton pregnancies at term gestation (37 weeks + zero days).

Types of interventions

We assumed the experimental type of intervention to be the maternal use of any upright position during the second stage of labour, compared with the control intervention of the use of any recumbent position. We included trials in which the intervention (upright or recumbent) was confined to the second stage of labour, and also where it was performed in the first stage of labour but also continued into the second stage.

The second stage of labour can be divided into two distinct phases: the latent phase (also known as the passive phase), and the active phase. We defined the latent phase as the period of time from full dilatation until the head has descended to the pelvic floor, with the mother experiencing no desire to push. We defined the active phase as the period from the head descending to the pelvic floor until the birth of the baby, with the mother having a strong desire to push (O'Driscoll 2003).

We classified studies as either a comparison of an upright versus a recumbent position in the latent phase of the second stage of labour, or a comparison of an upright versus a recumbent position in the active phase of the second stage of labour. We considered studies eligible for inclusion if it was intended that participants spent at least 30% of time in the relevant phase of second stage labour in the allocated position. Finally, studies that compared an upright position in both phases of the second stage with a recumbent position in both phases of the second stage formed a third group. There are three potential time phases in which the effects of different positions can be studied: namely the latent phase; the active; and both.

We initially categorised the birthing positions as upright (the main axis of the body was more than 45° from the horizontal) or recumbent (the main axis of the body was less than 45° from the horizontal).

Upright positions included:

sitting (on a bed);

sitting (on a tilting bed more than 45° from the horizontal);

squatting (unaided or using squatting bars);

squatting (aided with birth cushion);

semi‐recumbent (we classed this as an upright position if the main axis of the body (chest and abdomen) was 45° or more from the horizontal);

kneeling (upright, leaning on the head of the bed, or supported by a partner);

walking (only for comparison of positions in the latent phase).

Recumbent positions included:

lithotomy position;

lateral position (left or right);

Trendelenburg's position (head lower than pelvis);

knee‐elbow (all fours) position; this is considered recumbent because the axis of the trunk is horizontal;

semi‐recumbent (we classed this as a recumbent position if the main axis of the body (chest and abdomen) was less than 45° from the horizontal).

A number of other names have been used for birthing positions, including:

Fowler;

tug‐of‐war;

throne.

We delayed classifying these until after we had identified the trials. We planned to classify them from the methods section without knowledge of the trial results, again, using the dividing line of the body at 45° from the horizontal.

Some trials may compare positions with varying degrees of uprightness, which fall the same side of the 45° dividing line. For example, a study might compare the horizontal position (0°) with semi‐recumbent (40°). So long as the two groups clearly differed in degree of verticality, we classified them as 'more vertical' and 'less vertical'. We excluded such studies from the primary analysis, but included them in a secondary sensitivity analysis.

No studies reporting 'Fowler', 'tug of war' or 'throne' positions and no 'more vertical/less vertical' studies were found.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Operative birth (defined as caesarean section or vaginal instrumental birth)

Duration of second stage labour. (Since the assessment of the onset of second stage labour is susceptible to bias, we reported and analysed the randomisation‐to‐birth interval, where available)

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Caesarean section

Instrumental birth (forceps or ventouse (vacuum))

Trauma to birth canal, requiring suturing

Blood loss (greater than 500 mL) (or as defined by trial authors)

Prolonged second stage, defined as pushing for more than 60 minutes (or as defined by trial authors)

Maternal experience and satisfaction of labour

Baby outcomes

Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, requiring intervention

Apgar score of less than seven at five minutes (or as defined by trial authors)

Low cord pH less than 7.1 (or as defined by trial authors) (Following examination of the included studies, we found that only one study had recorded low cord pH. This was recorded as "less than 7.2". We had defined it as less than 7.1, therefore, we have left this outcome undefined and included the study as 'Low cord pH'.)

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

Need for ventilation

Perinatal death

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

We searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (19 September 2016).

The Register is a database containing over 22,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. For full search methods used to populate Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register, including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link to the editorial information about Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Cochrane Library and select the ‘Specialized Register ’ section from the options on the left side of the screen.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth Group review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set which has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Kemp 2013.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) software (RevMan 2014) and checked them for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third person.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random‐number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively‐numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding was unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses that we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ see Sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach

For this update we assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach as outlined in the GRADE handbook in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison ‐ upright position versus recumbent position.

Operative birth (defined as caesarean section or vaginal instrumental birth)

Duration of second stage labour

Trauma to birth canal, requiring suturing

Blood loss (greater than 500 mL) (or as defined by trial authors)

Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, requiring intervention

Low cord pH less than 7.1 (or as defined by trial authors)

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

We used the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool to import data from RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014) in order to create a ’Summary of findings’ table. We produced a summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

We used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

In future updates, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes or standard errors as appropriate using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6 respectively) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population Higgins 2011b). If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

It is not appropriate to include cross‐over design trials in this review.

Other unit of analysis issues

Multiple pregnancies

Only women with singleton pregnancies are included in this review. In future updates, trials of women with multiple pregnancies will be excluded.

Trials with more than one treatment arm

If we had identified a trial with more then one treatment arm, we would have divided the control group in the analysis to avoid double counting using methods described in Higgins 2011b.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, we will explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, that is, we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² (Higgins 2003) and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we explored it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using RevMan 5 software (RevMan 2014). Since all analyses included trials comparing different vertical and horizontal positions, we used the random‐effects model throughout. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we have discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful we did not combine trials.

For random‐effects analyses, the we have presented the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% CI, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we identified substantial heterogeneity, we investigated it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We considered whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, we used random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Time of epidural: sited in the first stage of labour or sited in the second stage of labour.

Type of epidural: traditional versus 'walking'. We classified low‐dose combined spinal epidurals and low‐dose infusion epidurals as 'walking'.

Nulliparous versus multiparous women.

Oxytocin used/not used in the second stage.

Due to insufficient data we were not able to carry out subgroup analyses 1, 3 and 4. However, these will be carried out in future updates of this review as more data become available.

We used the following outcomes in subgroup analyses.

Operative birth. Caesarean section or instrumental vaginal birth.

Duration of second stage labour. (Since the assessment of the onset of second stage is susceptible to bias, we have reported and analysed the randomisation‐to‐birth interval, where available).

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan 5 (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² statistic value.

Instrumental birth did not show substantial heterogeneity (I² = 25%) but we performed subgroup analysis due to its clinical relevance.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality. This involved an analysis limited to high‐quality trials. We excluded Theron 2011 from three analyses as we planned to restrict analysis to those trials with 'adequate' risk of bias judgements for allocation concealment and incomplete outcome data. Theron 2011 was assessed to be at high risk of incomplete outcome data. We also planned to exclude studies from this high‐quality analysis where the outcome assessor was not blinded, with the exception of the outcomes perinatal death, mode of birth and duration of second stage (randomisation to birth). None of the included studies blinded outcome assessment so this analysis did not take place. In future updates, if there are adequate data, we will perform this analysis.

In future updates, we will also perform a second sensitivity analysis, if appropriate, including trials comparing 'more vertical' with 'less vertical' as defined.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

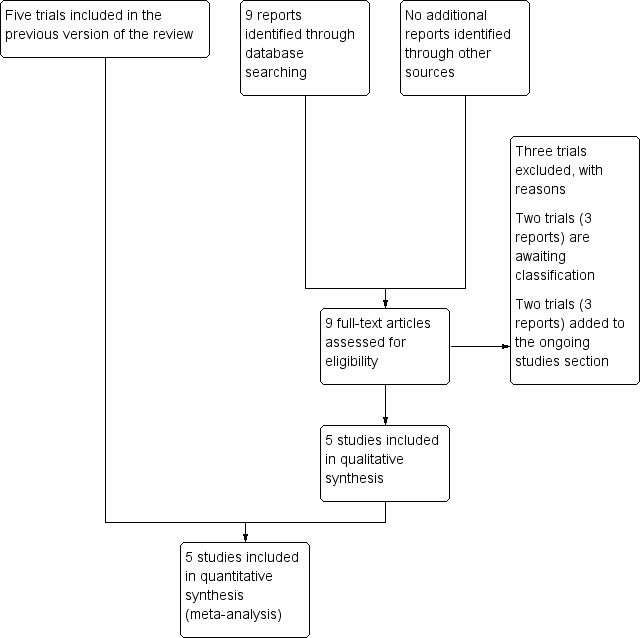

An updated search in September 2016 identified nine new reports of seven trials. None of the new studies met the inclusion criteria although two (Simarro 2011; Walker 2012) are awaiting assessment pending further information from the trial authors ‐ see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification. We excluded three trials: Amiri 2012, Martin 2011, and Zaibunnisa 2015. Two studies are ongoing (Brocklehurst 2016; Hofmeyr 2015 ‐ see Characteristics of ongoing studies). See Figure 1 (PRISMA 2009). Please see the previous version of this review for details of previous searches (Kemp 2013).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

This review now includes five trials (Boyle 2001; Downe 2004; Golara 2002; Karraz 2003; Theron 2011‐ abstract only) having excluded six trial in total (Amiri 2012; Asselineau 1996; Collis 1999; Danilenko‐Dixon 1996; Martin 2011; Zaibunnisa 2015).

Included studies

We have included five studies, involving 879 women, in the review, see Characteristics of included studies.

Methods

All five studies are randomised controlled trials using individual randomisation.

Participants

Boyle 2001 and Karraz 2003 included both nulliparous and multiparous women in induced or spontaneous labour with an effective low‐dose mobile epidural. Golara 2002 also compared women with mobile epidurals but only included nulliparous women.

Downe 2004 included primiparous women with an effective traditional epidural. Theron 2011 also only included nulliparous women, but did not specify whether the epidural was mobile or traditional.

All trials only included women with singleton pregnancies at term (37 weeks or above gestation), or above 36 weeks' gestation (Downe 2004; Karraz 2003).

Settings

All trials took place in hospital settings in either the UK (Boyle 2001; Downe 2004; Golara 2002; Theron 2011) or France (Karraz 2003).

Interventions and comparisons

All the included studies had two intervention groups that could be classified into an upright or recumbent position using the criteria in the Methods section.

Downe 2004 compared 'lateral (left or right facing positions)' and 'sitting positions (supported upright sitting position)'. Golara 2002 compared 'recumbent (as much time as possible in bed or a chair)' and 'upright (as much time as possible during the passive phase either standing or walking)' and after one hour, their chosen pushing position was allowed. Boyle 2001 compared ambulant (walking around for at least 15 minutes every hour, up to the point of active voluntary pushing) and non‐ambulant (usual care, where the women were non‐ambulant except for the majority of the labour). Karraz 2003 compared 'ambulatory (walking, sitting in a chair, reclining in semi‐supine position)' with 'non‐ambulatory (not allowed to sit or walk, had to remain in the supine, semi‐supine or lateral position)'. Theron 2011 compared a "sitting position" with a "lateral position" during the passive second stage of labour, usually one hour.

Three studies (Downe 2004; Golara 2002; Theron 2011) specifically restricted the period of randomisation to the second stage of labour. One study Boyle 2001, explicitly, and one Karraz 2003, implicitly, also included the first stage of labour within the period of randomisation. However, since both studies included the passive second stage within the period of randomisation, we have included them in the present review. We recognise that there will be some overlap between these studies and the Cochrane Review 'Maternal positions and mobility in the first stage of labour' (Lawrence 2009).

All the studies had their own entry and exclusion criteria which can be seen in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes

All studies reported instrumental birth, caesarean section and spontaneous vaginal birth. Trauma to the birth canal requiring suturing was reported by two (Downe 2004; Golara 2002). Downe 2004, was the only study to report instrumental deliveries for fetal distress. Golara 2002 was the only study to report low cord pH and admission to neonatal intensive care unit. The duration of second stage of labour was reported by Downe 2004 and Karraz 2003. Golara 2002, also reported duration of second stage of labour but only the median and range. We contacted the trial author to see if the raw data or mean and standard deviations were available but these were not obtained so we could not include the data in the review.

Funding sources

Downe 2004 and Karraz 2003 were funded by the departments where the trials took place. It is not clear (Golara 2002), or not stated (Boyle 2001; Theron 2011), how the remaining trials were funded.

Excluded studies

We excluded six studies (Amiri 2012; Asselineau 1996; Collis 1999; Danilenko‐Dixon 1996; Martin 2011; Zaibunnisa 2015).

We excluded one study because it was not a randomised controlled trial (Asselineau 1996). We excluded Collis 1999 because it compared upright versus recumbent position in the first stage of labour only (when cervical dilation was identified, the women returned to their beds). We excluded the Danilenko‐Dixon 1996 study because it did not compare an upright position with a lateral position (it compared two recumbent positions (supine and lateral). We excluded Amiri 2012 and Zaibunnisa 2015 because they included participants without epidural, and Martin 2011 compared modified Sims position (lateral position) with Sims (lateral position) or Semi‐fowler positions (semi‐recumbent position).

For more details, see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

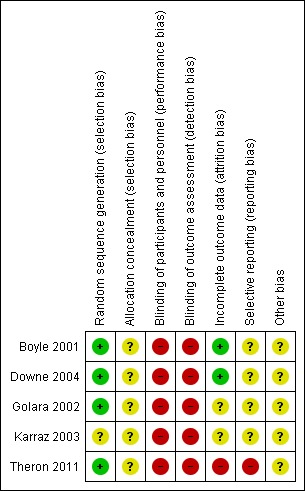

(See Summary of risk of bias Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Four trials reported either using 'computer‐generated random numbers' (low risk of bias) (Boyle 2001; Downe 2004; Golara 2002; Theron 2011) and one said that participants were "randomly divided into two groups" (Karraz 2003) (unclear risk of bias).

Three of the four used opaque envelopes (Downe 2004) or sealed brown envelopes (Golara 2002) or sealed envelopes (Boyle 2001), but since the numbering, sealed status, or opacity of the envelopes was not reported in all cases, the risk of bias was judged to be 'unclear'. Two trials (Karraz 2003; Theron 2011) did not report the allocation sequence concealment (Karraz 2003; Theron 2011) and we also rated them as 'unclear'.

Blinding

None of the studies masked the participants or the assessor to the treatment allocation (we assessed all of the studies as 'high' risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies (Boyle 2001; Downe 2004) reported results for all participants randomised (low risk of bias) but the other studies were classed as having an 'unclear' (Golara 2002; Karraz 2003) or 'high' (Theron 2011) risk of bias from post‐randomisation exclusions. Theron 2011 reported 43 participants who dropped out after consent but did not clarify if this was also post randomisation.

Selective reporting

We rated Theron 2011 as being at 'high risk' of reporting bias because it did not report the secondary outcomes of maternal acceptability, cardiotocograph (CTG) abnormality and neonatal outcomes, and had not registered the trial protocol. The other four trials had also not registered trial protocols (Boyle 2001; Downe 2004; Golara 2002; Karraz 2003) and we rated these as 'unclear' risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

None of the studies had independently registered their sample size, primary endpoint or other aspects of the analysis plan. Only one (Theron 2011) reported that the intended sample size of 300 was larger than the achieved one of 77. We rated all five included studies as being at an 'unclear' risk of other bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison: upright position versus recumbent position

We identified data for eight of this review's pre‐specified outcomes. We were able to perform six meta‐analyses in this review.

Primary outcomes

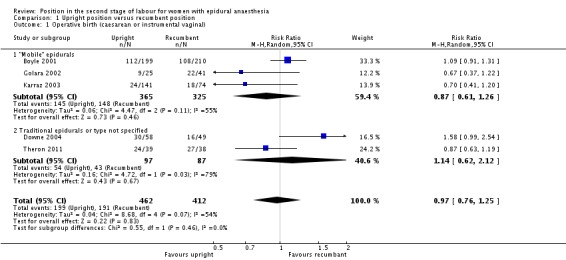

Operative birth (defined as caesarean section or vaginal instrumental birth)

Overall, we identified no clear difference between upright and recumbent positions on the rates of operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal) (average risk ratio (RR) 0.97; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.76 to 1.25; five trials; 874 women; random‐effects; Tau² = 0.04, I² = 54%; moderate‐quality evidence (Analysis 1.1)).

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 1 Operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal).

We excluded Theron 2011 as part of a sensitivity analysis for high risk of bias and this produced a similar result (average RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.39; four trials; 797 women; random‐effects; I² = 60%).

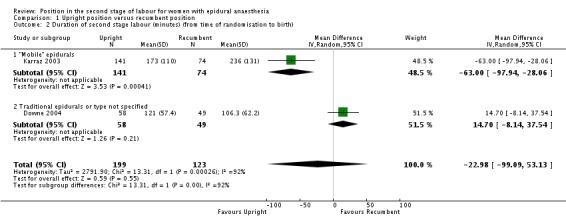

Duration of second stage labour

We also identified no clear difference and inconsistent results for duration of the second stage of labour measured as the randomisation‐to‐birth interval in minutes (mean difference (MD) ‐22.98 minutes; 95% CI ‐99.09 to 53.13; two trials, 322 women; random‐effects; Tau² = 2791.90, I² = 92%; very low‐quality evidence (Analysis 1.2)). Note the high degree of heterogeneity between the two trials included in the analysis of duration of second stage of labour.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 2 Duration of second stage labour (minutes) (from time of randomisation to birth).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

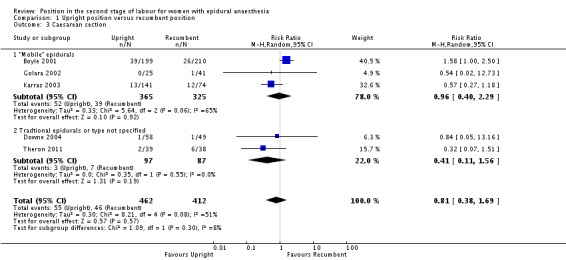

Caesarean section

We identified no clear differences between upright and recumbent position on caesarean section (average RR 0.81; 95% CI 0.38 to 1.69; five trials, 874 women; random‐effects; Tau² = 0.30, I² = 51% (Analysis 1.3)).

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

Excluding Theron 2011 as part of a sensitivity analysis yielded a similar result (average RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.46 to 2.03; four trials; 797 women; random‐effects; I² = 47%).

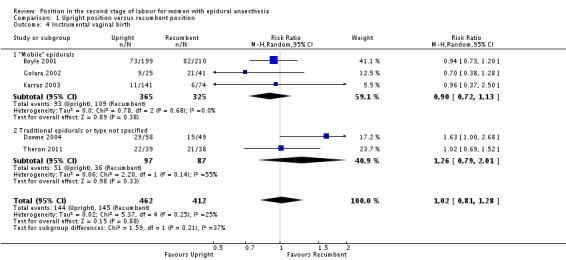

Instrumental birth (forceps or ventouse (vacuum))

We identified no clear differences between upright and recumbent position on instrumental birth (average RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.28; five trials, 874 women; random‐effects; Tau² = 0.02, I² = 25% (Analysis 1.4)).

Analysis 1.4.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 4 Instrumental vaginal birth.

Excluding Theron 2011 as part of a sensitivity analysis produced a similar result (average RR 1.02; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.43; four trials; 797 women; random‐effects; I² = 44%).

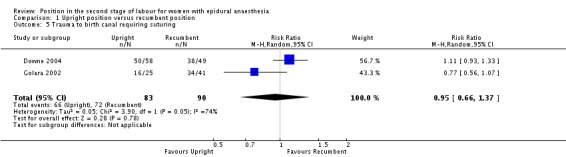

Trauma to birth canal, requiring suturing

Nor did we identify any effect from position on trauma to birth canal requiring suturing (average RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.37; two trials, 173 women; random‐effects; Tau² = 0.05, I² = 74%; very low‐quality evidence (Analysis 1.5)).

Analysis 1.5.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 5 Trauma to birth canal requiring suturing.

There were no data reported on blood loss greater than 500 mL (or as defined by the trial authors), prolonged second stage or maternal experience and satisfaction with labour.

Baby outcomes

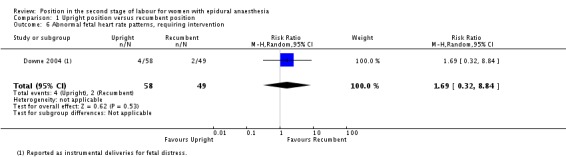

Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, requiring intervention

We identified no clear differences in this outcome which was only reported in one trial (Downe 2004) as instrumental deliveries for fetal distress (RR 1.69; 95% CI 0.32 to 8.84; one trial, 107 women; very low‐quality evidence (Analysis 1.6)).

Analysis 1.6.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 6 Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, requiring intervention.

Low cord pH less than 7.1 (or as defined by trial authors)

We identified no clear differences between groups in numbers of babies born with low cord pH (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.18 to 2.10; one trial, 66 infants; very low‐quality evidence (Analysis 1.7)).

Analysis 1.7.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 7 Low cord pH.

Admission to neonatal intensive care unit

We identified no clear differences in rates of admission to neonatal intensive care unit between the two groups ‐ with just one admission in the recumbent group (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.02 to 12.73; one trial, 66 infants; very low‐quality evidence (Analysis 1.8)).

Analysis 1.8.

Comparison 1 Upright position versus recumbent position, Outcome 8 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

There were no analysable data on Apgar scores, and no data reported on need for ventilation or perinatal death.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This updated review includes five randomised controlled trials, involving 879 women ‐ no new studies were included for this update, although two trials (Simarro 2011; Walker 2012) are awaiting assessment pending further information from the trial authors. Two trials (Brocklehurst 2016; Hofmeyr 2015) are ongoing and will be incorporated into this review in a future update.

We identified no clinically important or clear effects of upright compared with recumbent positions on any of the predefined outcomes, namely, total operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal), duration of second stage of labour, caesarean section, instrumental birth, trauma to birth canal requiring suturing, low cord pH or admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review includes all available randomised controlled trials which test the theory of whether gravity might help the process of birth.

Quality of the evidence

The studies were relatively small so the confidence intervals around each effect size were large. All of the studies had some methodological concerns; lack of registration, unclear randomisation concealment, or post‐randomisation exclusions, which means the results should be interpreted with caution. The studies also compared different upright and recumbent positions, which may explain the heterogeneity observed between Downe 2004 and the other trials.

One study (Downe 2004) involved women with traditional epidurals, three (Boyle 2001; Golara 2002; Karraz 2003) included women with 'walking' epidurals and one (Theron 2011) did not report the type of epidural. These differences may also partly explain the heterogeneity of the results.

Since the confidence intervals around each estimate were wide, clinically important effects were not ruled out, so women with an epidural should be encouraged to use whatever position they find most comfortable during their second stage of labour.

There was some heterogeneity among the five studies in their effect on instrumental vaginal birth, and a very large and highly statistically significant degree of heterogeneity among the two studies (Downe 2004; Karraz 2003) that recorded duration of the second stage. For both outcomes the trial by Downe 2004 differed from the other trials, namely more instrumental deliveries and a longer second stage in the upright group. One explanation is potential bias from failure of randomisation (Karraz 2003) or allocation concealment (Downe 2004; Karraz 2003). Another, is that the Downe 2004 trial compared sitting (upright) with the left/right lateral (recumbent) position. The benefits of the upright position may be negated if the woman rests on the sacrum and ischial tuberosities (Gardosi 1989). This may rotate the sacrum forward and reduce the anterior posterior pelvic outlet dimensions (Borell 1957).

In the present review we have not considered studies which assess positions which free the pelvis to expand a little compared with those where the pelvis is fixed. Such a comparison would test if positions which let the pelvis expand and give more room for the baby to pass through, might help. Sitting upright on a bed would be a 'pelvis fixed' position. We will consider this comparison in the next update.

We assessed the quality of the evidence using the GRADE approach for the seven prespecified GRADE outcomes for the comparison of upright position versus recumbent position (see Table 1). We assessed the evidence for operative birth as being of moderate quality. We assessed all other outcomes (duration of second stage, blood loss greater than 500 mL, abnormal fetal heart rate patterns requiring intervention, low cord pH less than 7.1 and admission to neonatal intensive care unit) as having very low‐quality evidence. We downgraded outcomes due to design limitations in studies contributing data, inconsistency, and imprecision of effect estimates.

Potential biases in the review process

It is possible that, since the studies were carried out on women who had the type of epidural that allowed them to ambulate, these may not be the population of women who would have had a longer second stage of labour in the first place.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of this updated review both agree and disagree with another Cochrane Review comparing positions in second stage in women without epidural analgesia (Gupta 2012). Similar results were seen for duration of labour, caesarean section and admission to neonatal intensive care. Women without epidural analgesia in an upright position had fewer assisted deliveries, and less abnormal fetal heart rates noted, but experienced more second‐degree tears than those in recumbent positions without epidural analgesia.

Authors' conclusions

The results of this review demonstrate that there are insufficient data to guide practice about the best position for the second stage of labour for women with an epidural. Women should be encouraged to use the position that they feel most comfortable in, during the second stage of labour.

More studies with larger sample sizes will need to be conducted in order for solid conclusions to be made about the effect of position on labour in women with an epidural. Such studies should have the protocol registered, so that sample size, primary outcome, analysis plan, etc. are all clearly prespecified. The time of randomisation should be recorded since this is the only unbiased starting time point from which the effect of position on duration of labour can be estimated. Future studies might wish to include an arm in which women were allowed to choose the position in which they felt most comfortable. Future studies should ensure that both compared positions are acceptable to women, that women can remain in them for most of the late part of labour, and report the number of women who spend time in the allocated position and the amount of time they spend in this or other positions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Emily Kemp and Claire J Kingswood for their contribution to the initial version of this review (Kemp 2013).

We would also like to thank Bita Mesgarpour for translating and assessing Amiri 2012.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

We are grateful to Anna Cuthbert (Research Associate with Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth) for her help in preparing this 'no new studies' update. Anna assessed studies for inclusion and prepared the updated review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

Upright position versus recumbent position

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Operative birth (caesarean or instrumental vaginal) | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.76, 1.25] |

| 1.1 "Mobile" epidurals | 3 | 690 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.61, 1.26] |

| 1.2 Traditional epidurals or type not specified | 2 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.62, 2.12] |

| 2 Duration of second stage labour (minutes) (from time of randomisation to birth) | 2 | 322 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐22.98 [‐99.09, 53.13] |

| 2.1 "Mobile" epidurals | 1 | 215 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐63.0 [‐97.94, ‐28.06] |

| 2.2 Traditional epidurals or type not specified | 1 | 107 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 14.70 [‐8.14, 37.54] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.38, 1.69] |

| 3.1 "Mobile" epidurals | 3 | 690 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.40, 2.29] |

| 3.2 Tradtional epidurals or type not specified | 2 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.41 [0.11, 1.56] |

| 4 Instrumental vaginal birth | 5 | 874 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.81, 1.28] |

| 4.1 "Mobile" epidurals | 3 | 690 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.72, 1.13] |

| 4.2 Traditional epidurals or type not specified | 2 | 184 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.79, 2.01] |

| 5 Trauma to birth canal requiring suturing | 2 | 173 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.66, 1.37] |

| 6 Abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, requiring intervention | 1 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.69 [0.32, 8.84] |

| 7 Low cord pH | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.18, 2.10] |

| 8 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | 1 | 66 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.02, 12.73] |

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 19 September 2016 | New search has been performed | Search updated, nine new trial reports of seven trials added. No new studies were included: two (Simarro 2011; Walker 2012) are awaiting assessment pending further information from the trial authors, three trials were excluded (Amiri 2012; Zaibunnisa 2015; Martin 2011). Two trials are ongoing (Brocklehurst 2016; Hofmeyr 2015). |

| 19 September 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No new included studies identified for this update 'Summary of findings' table added |

Differences between protocol and review

The methods have been updated and the current standard methods text for Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth has been incorporated. This includes the use of GRADE and inclusion of a 'Summary of findings' table. We have restructured the Plain Language Summary using the standardised headings developed by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT in a consultant maternity unit in Hertfordshire, UK Participants were recruited between August 1999‐December 2000 |

|

| Participants | Primiparous (n = 295) and multiparous (n = 113) women (total 408) in either induced or spontaneous labour with a working low dose, CSE in the first stage of labour, and a Modified Bromage score of ≥ 3 | |

| Interventions | The ambulant group were encouraged to walk around for at least 15 min in every hour, up to the point of active voluntary pushing, i.e. including the passive second stage of labour The non‐ambulant group received 'usual care'. This meant remaining non‐ambulant except for toilet purposes for the majority of the labour Among primigravidae the mean time in minutes spent ambulating (SD) was 46 (51) in the ambulant group and 18 (33) in the non‐ambulant. Among multigravidae the mean time in minutes spent ambulating (SD) was 37 in the ambulant group and 11 in the non‐ambulant. Note standard deviations were not reported for multigravidae. Use of oxytocin in the second stage was not reported. |

|

| Outcomes |

Maternal outcomes

Baby outcomes

|

|

| Notes | Trial took place in consultant maternity unit in Hertfordshire, UK ‐ funding source unknown | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A computer‐generated random number sequence was used |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation was achieved by the use of sequentially‐numbered sealed envelopes. Opacity not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up recorded and only short‐term outcomes reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Neither the trial, nor the protocol was registered |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The trial protocol was not registered |

| Methods | A pragmatic prospective RCT, in a consultant‐led maternity unit in the East Midlands, UK. Recruitment from June 1993‐May 1994. |

|

| Participants | 107 nulliparous women using traditional epidural analgesia, set up in the first stage of labour, maintained by bolus doses of local anaesthetic, and reaching the second stage without contraindication to spontaneous birth. In most cases the epidural was continued into the second stage of labour, a passive hour was allowed followed by encouraged pushing by the midwife. Entry criteria: nulliparity, uncomplicated pregnancy, no history of uterine surgery, live single cephalic fetus with no abnormality detected, once women in labour at 36 weeks' gestation or greater, with effective epidural analgesia, eligibility was confirmed Exclusion criteria: breech position, severe pregnancy‐induced hypertension, pre‐eclampsia or eclampsia, severe intrauterine growth retardation, known intrauterine fetal death, presence of uterine scar. The proportions of participants in spontaneous or induced labour were not reported. Use of oxytocin in the second stage was not reported. |

|

| Interventions | 58 were allocated to the supported upright sitting position (normal practice in the unit). 6 of these used the lateral position. 49 were allocated to use the left or right facing lateral position whichever was most comfortable. 12 of these used the sitting position. |

|

| Outcomes |

Maternal outcomes

Baby outcomes

|

|

| Notes | Funding was from the HSA Hospital Trust/ SDH Scholarship Fund/ Southern Derbyshire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Opaque envelopes stapled to patient notes. Numbering and sealing not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The main outcomes were reported for all 107 women randomised |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Trial protocol not registered |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Trial protocol not registered |

| Methods | RCT, conducted in a university teaching hospital in London, UK The period of recruitment was not recorded |

|

| Participants | Entry criteria: primigravidae, singleton fetus in vertex presentation, 37 weeks or greater, continuous spinal catheter sited during the first stage and in situ, achieved full dilatation, motor function adequate for mobilisation Exclusion criteria: inadequate motor function, received pethidine 4 h before full dilatation Analgesia was maintained by intermittent bolus injections. A 1‐h passive phase was allowed in the second stage 66 (upright = 25, recumbent = 41). 13 (7 recumbent, 6 upright) had induced labour. 8 (4 in each group) were given oxytocin in the second stage |

|

| Interventions | 25 women allocated to the upright group were asked to spend as much as possible of the passive phase of the second stage standing or walking. Of these 22 (88%) were upright for more than 30 min 41 women allocated to the recumbent group were asked to be in bed or a chair during the passive phase. Of these 27 (65%) spent more than 30 min in bed, 8 (20%) sat in a chair for more than 30 min and 6 (15%) were walking or standing |

|

| Outcomes |

Maternal outcomes

Baby outcomes

|

|

| Notes | Authors employed at Maternal and Fetal Research Unit, St. Thomas’s Hospital and Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital, London, UK. It is not clear how the study was funded | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated random numbers. A copy [of the randomisation sequence] was kept safe to ensure no violation of randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Sealed brown envelopes. Opacity and numbering not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | There is a discrepancy in the number of participants reported. The total randomised is stated to be 70, with 7 post‐randomisation withdrawals (i.e. 63 remaining). But the number reported in the remainder of the paper is 66 |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Trial protocol not registered |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Trial protocol not registered |

| Methods | A randomised prospective study, in a regional maternity hospital in France The randomisation ratio was 2:1 ambulatory: recumbent Recruitment from February 1999‐April 2001 |

|

| Participants | Entry criteria: 36‐42 weeks pregnant, a singleton pregnancy, cephalic presentation, uncomplicated pregnancies Exclusion criteria: pre‐eclampsia, previous caesarean section All participants had a low‐dose "ambulatory" epidural using intermittent bolus doses (0.1% ropivacaine and 0.6 micro grams/mL sufentanil) titrated against pain relief Women in spontaneous (86 ambulatory, 45 non‐ambulatory) and induced labour were included Use of oxytocin in the second stage was not reported 221 participants were included. 144 were allocated to the upright position and 77 to recumbent |

|

| Interventions | Women allocated to the ambulatory group were allowed to walk if they had acceptable analgesia, systolic BP > 100 mmHg, and were able to stand on 1 leg. The number who walked and the time spent walking were not reported Women allocated to the non‐ambulatory group were not allowed to sit or walk. They were only allowed to lie supine, semi supine or in a lateral position on the bed. The number who complied, and the time spent in each position were not reported |

|

| Outcomes |

Maternal outcomes

Baby outcomes

|

|

| Notes | This study was conducted at the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, Beauvais Central Hospital, France.The Departments of Anesthesiology and Obstetrics and Gynecology funded this study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomly divided into 2 groups. Randomised in 2:1 ratio (upright: recumbent) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not recorded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | No data reported for 6 post‐randomisation exclusions (3 per group) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Trial protocol not registered |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Trial protocol not registered |

| Methods | RCT Single centre. University Teaching Hospital, UK |

|

| Participants | Nulliparous women at term. Single fetus. Epidural sited and analgesia established The type of epidural, and whether it was a 'walking' epidural was not reported Numbers of spontaneous and induced labours not reported Use of oxytocin in the second stage not reported Random allocated using computer randomisation 39 women allocated to sitting. 38 allocated to lateral position |

|

| Interventions | Sitting for 1 h passive second stage of labour Lateral position for 1 h passive second stage of labour |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | 120 women consented. 43 dropped out after consent Not stated how study was funded (abstract only) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not recorded |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned ‐ assumed unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 43 participants dropped out after consent. Unclear if this was post randomisation |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Secondary outcomes of maternal acceptability, CTG abnormality and neonatal outcomes not reported. Trial protocol not registered |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Intended sample size 300. Study stopped after 77 recruited |

BP: blood pressure CSE: combined spinal epidural CTG: cardiotocograph RCT: randomised controlled trial SD: standard deviation

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Amiri 2012 | Trial compared positions in labour for women without epidural |

| Asselineau 1996 | This was not a randomised trial. Translation from the French indicates that the ambulatory group was selected by having no contraindications to ambulation and gave consent. The non‐ambulatory group was made up of women who were "chosen at random" from women receiving epidural analgesia. |

| Collis 1999 | This trial compared upright versus recumbent in the first stage of labour, "The time at which full cervical dilatation was diagnosed was recorded and all mothers returned to bed". |

| Danilenko‐Dixon 1996 | The trial compared two recumbent positions, supine and lateral. |

| Martin 2011 | Trial compared modified Sims position with Sims or Semi‐fowler positions. None of these options were upright positions so did not satisfy this review's inclusion criteria. |

| Zaibunnisa 2015 | Trial compared positions in labour for women without epidural. |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | 150 women at full dilatation |

| Interventions | Intervention group: delay pushing and change position (hands and knees, sitting lateral, kneeling and supine). Delivered in lithotomy Comparison group: delay pushing, rest in horizontal position without postural changes |

| Outcomes | Mode of delivery Perineal trauma Duration of second stage |

| Notes | Awaiting clarification of intervention from study authors. May be eligible for inclusion |

| Methods | RCT |

| Participants | 199 women randomised Nulliparous and multiparous women (gestational age > 36 or < 42 weeks), single fetus in cephalic presentation, spontaneous or induced labour, and effective epidural anaesthesia with a standardised continuous‐infusion technique |

| Interventions | Intervention group (103 participants): alternative model of birth (study group) AMB consisted of 2 consecutive interventions during the second stage of labour. Firstly, women move to different positions while delaying the onset of pushing during the passive phase and, secondly, women were placed in the modified lateral Gasquet position during the active pushing phase. Comparison group (96 participants): In the traditional model of birth (TMB), women were encouraged to perform pushing efforts with each contraction, as soon as they were found to be completely dilated. They had no postural changes, and delivery was in the lithotomy position. |

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes were rates of AVD (defined by the use of forceps, vacuum, spatulas, or fundal pressure, also known as Kristeller maneuver) and PT, defined as trauma requiring suturing (episiotomy, tear, or both). Secondary outcomes were length of the second stage (duration from full dilatation to delivery), duration of pushing efforts (from starting active pushing to delivery), umbilical arterial cord blood pH, Apgar scores, birthweight, and FH station at full dilatation (classified by FH unengaged and FH engaged or below inlet). |

| Notes | Awaiting clarification of intervention from authors. May be eligible for inclusion |