Abstract

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a heterogeneous condition and an important cause of acquired disability in children. Evidence supports early treatment to prevent future complications. This relies on prompt diagnosis, achieved by a high index of clinical suspicion and supportive evidence, including the detection of joint and or tendon inflammation. Ultrasound is a readily accessible, well-tolerated, safe and accurate modality for assessing joints and the surrounding soft tissues. It can also be used to guide therapy into those joints and tendon sheaths resistant to systemic treatments. Ultrasound imaging is highly operator dependent, and the developing skeleton poses unique challenges in interpretation with sonographic findings that can mimic pathology and vice versa. Ultrasound technology has been rapidly improving and is more accessible than ever before. In this article, we review the normal appearances, highlight potential pitfalls and present the key pathological findings commonly seen in JIA.

INTRODUCTION

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an umbrella term encompassing a group of disorders characterized by synovial inflammation. JIA is a diagnosis of exclusion and is the most common rheumatic disorder of childhood, with a prevalence of 0.6–1.9 per 1000.1 It is defined as arthritis of unknown cause lasting over 6-week duration in a child less than 16 years of age.

Disorders classified as JIA have been grouped according to clinical and biochemical markers to aid detection, treatment and research. A widely used classification is the International League of Associations for Rheumatology,2 where presentation may be with arthritis in a single joint, <4 joints—oligoarticular disease [oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (OJIA)], multiple joints—polyarticular [polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (PJIA)] or with systemic features (systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis). Further subtypes are also described (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) according to frequency, age of onset and gender distribution3

| JIA subtype | Percentage of all JIA | Onset age | Sex ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic arthritis | 4–17% | Throughout childhood | F = M |

| Oligoarthritis | 27–56% | Early childhood; peak at 2–4 years | F >>> M |

| R+veJIA | 2–7% | Late childhood or adolescence | F >> M |

| R−veJIA | 11–28% | Biphasic distribution; early peak at 2–4 years and later peak at 6–12 years | F >> M |

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | 3–11% | Late childhood or adolescence | F >> M |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 2–11% | Biphasic distribution; early peak at 2–4 years and later peak at 9–11 years | F > M |

| Undifferentiated arthritis | 11–21% |

F, female; M, male; R+veJIA, rheumatoid factor-positive polyarthritis; R−veJIA, rheumatoid factor-negative polyarthritis.

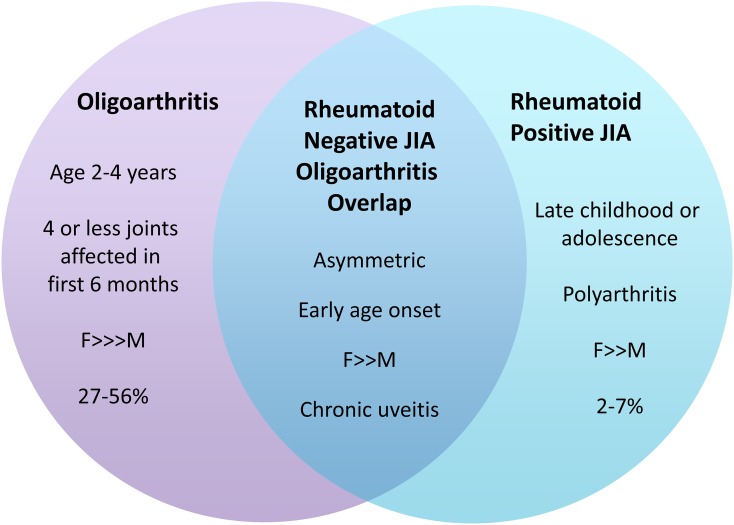

Other classification systems include those provided by the American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism. None of the classification systems are perfect, and it is noteworthy that none take tendon sheath inflammation, which is a classical feature of JIA, into account. Patients can meet criteria for >1 subtype, as seen in rheumatoid factor-negative polyarthritis, PJIA and subtypes of OJIA (Figure 1). The implication is that this inter group heterogeneity can cause difficulty in measuring effects of treatment and follow-up, by either clinical or radiological means. As understanding of the genetic, clinical and biochemical make-up of these diseases advances, we may find future reorganization of the classifications.4,5

Figure 1.

Heterogeneity within juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) classifications: features of some of the disease subtypes can overlap with others, causing difficulties in accurate classification. This has implications on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. F, female; M, male.

AETIOLOGY

Although the precise aetiology of JIA is unknown, there are suggestions that infections and vaccinations may be triggers in children with genetic susceptibility. There is no confirmed evidence of an environmental trigger, but support for genetic predisposition comes from scrutiny of the Utah Genealogical Database. Extended families of patients with JIA were identified, and an estimate of sibling recurrence risk was found to be approximately 30 times that of the general population.6

Consistent genetic associations with certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles are recognized (Table 2) with a striking association with HLA-A2, which is seen across different JIA categories.6,7

Table 2.

Self-tissue antigen and environmental risk factors associated with the development of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)5,8

| JIA category | HLA association | Protective alleles | Suspected infective triggers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligoarthritis | A2, DRB1*01, DRB1*08, DRB1*11, DRB1*13, DPB1*02, DQA1*04, DQB1*04 | (Protective HLA DRB1*04, DRB1*07) | Parvovirus B19 Epstein–Barr virus |

| R−veJIA | A2, DRB1*08, DQA1*04, DPB1*03 | ||

| R+veJIA | DRB1*04, DQA1*03, DQB1*03 | DQA1*02 | |

| Enthesitis related Arthritis | B27, DRB1*01, DQA1*0101, DQB1*05 | Enteric bacteria | |

| Psoriatic arthritis | DRB1*01, DQA1*0101 | DRB1*04, DQA1*03 | Enteric bacteria |

| Systemic arthritis | Bartonella Henselae n = 1 | ||

| JIA not specified |

Mycoplasma pneumonia Streptococcus pyogene Chlamydia pneumonia Chlamydia trachomatis Chlamydophila pneumoniae |

HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

The genes controlling these alleles are thought to confer HLA-specific window of susceptibility related to patient demographics during which the subject is most at risk of developing an autoimmune process. This effect is seen to be strongest in OJIA in which certain HLA alleles confer a variable risk according to age.7 At other ages, certain alleles are likely to be neutral or even protective as in the case of HLA-DRB1*04, which is protective for OJIA but is a risk factor for rheumatoid factor-positive polyarthritis.3,7

PATHOGENESIS OF JOINT DAMAGE

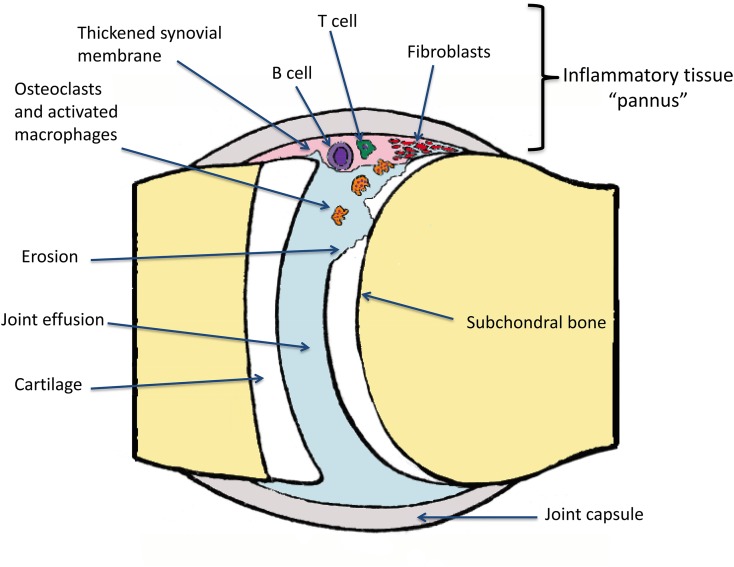

Synovitis in JIA is characterized by infiltration by T-cells, B-cells and activated macrophages.8 The release of proinflammatory cytokines stimulates arrival of further inflammatory cells. This inflammatory soup contributes to the formation of pannus (Figure 2). Synovial fibroblast, chondrocyte and osteoclast roles are modified such that joint damage occurs via degradation of the cartilage and then eventually bone erosion.9,10 As the cartilage and articular bone are damaged, classical features of joint space loss and erosions and in advanced disease, ankylosis, growth disturbance and joint misalignment are seen.

Figure 2.

Pathogenesis of joint damage: an unknown inciting trigger activates T and B cells of the adaptive immune system. These immune orchestrators promote joint infiltration by activating macrophages and promoting osteoclastic activity. Over time, fibroblast and chondrocyte functions are altered, impairing healing. The synovium becomes thickened and the cartilage is degraded, exposing the subchondral bone to further erosive damage. Fluid can collect in the joint forming an effusion.

ROLE OF IMAGING

It has been suggested that there is a “window of opportunity” in early disease during which prompt treatment delays progression and induces higher rates of remission.11 Although JIA is a clinical diagnosis, imaging plays an important role in support of the diagnosis, monitoring of therapeutic response and detecting chronic changes. The mainstay of imaging remains plain film, which is readily accessible, reproducible and suitably placed to longitudinally monitor bone and joint changes over time.

Radiographs are, however, insensitive for inflammatory soft tissue changes which form a significant part of the disease process.12,13 In the past 15 years, there has been a shift in the management of JIA with early aggressive treatment.8,14,15 This requires detection of soft tissue abnormalities prior to the development of established radiographic changes.

MRI is frequently utilized in JIA to assess joint, bone marrow and soft tissue changes, in particular to evaluate bone marrow oedema and synovitis. Whilst MRI provides excellent soft tissue and bone definition, there are certain disadvantages in children, namely long examination times, the need for sedation or general anaesthesia in young children, relative lack of access and the need to administer gadolinium to accurately diagnose synovitis.16 MRI is also limited to evaluating predetermined joints or areas of interest, and it is time consuming to examine multiple regions of the skeleton.

Ultrasound use has been recommended routinely in hands of experienced operators.17–19 It has many advantages in children and is increasingly being utilized in JIA to confirm suspected clinical findings, define affected anatomical compartments, guide arthrocentesis and perform intra-articular therapy.20 Ultrasound is an ideal modality to use in children, being well accepted, non-ionizing, dynamic, accessible and quick, and does not require sedation or general anaesthesia. It can be used to compare symptomatic and asymptomatic sites and is easily repeatable. There are, however, pitfalls and a learning curve when performing musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSK-US) in children, and the technique is operator dependent.

In the following review, we interrogated the literature for the current evidence of ultrasound in JIA by performing keyword searches in PubMed. The following terms were used: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, inflammatory arthritis, musculoskeletal ultrasound, cartilage and normal variants.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR ULTRASOUND IN JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

In common with other ultrasound examinations in children, establishing a good rapport with the child and parents is a primary consideration, with a child-friendly ultrasound environment being an important component in this.

MSK-US imaging requires a high-resolution image, and therefore linear transducers with frequencies between 15 MHz and 18 MHz are preferred. Given the wide age range encountered in paediatric imaging, it is vital to modify transducer selection so that an appropriate size is used for the body part of interest. For example, using a “hockey-stick” transducer would be appropriate to evaluate a finger in an adolescent but is unlikely to be appropriate to examine the wrist, whereas for a 2-year old, a “hockey-stick” transducer is much more appropriate than a standard 15 MHz linear transducer for wrist assessment.

COMPOUND AND HARMONIC IMAGING

Compound ultrasound imaging is a technique where the transducer angles the beam over several different angles of insonation and the resulting image is composed of the resulting echoes from each of these. This leads to decreased speckle-, noise- and angle-related artefacts, which have been shown to be of benefit in soft tissue imaging, particularly for structures containing internal fibrillary structures such as tendons and muscles.21 The imaging of tendons and muscles can be affected by the angle of insonation, with apparent reduced echogenicity seen where the beam is not perpendicular to the fibres (anisotropy). Compound imaging is a very useful tool in children who tend to wriggle and move, causing greater difficulty in maintaining an ideal angle of insonation.

Harmonic imaging utilizes the phenomenon of non-linear propagation of ultrasound waves through the body leading to multiples of the primary echo frequency returned from reflective body interfaces (harmonics) around the primary transducer frequency. Using the second harmonic in addition to the primary frequency to generate the ultrasound image leads to an improved signal-to-noise ratio and increased axial resolution compared with conventional ultrasound.

Taking into consideration the technical advantages described above, when performing MSK-US in children, it is recommended to use an appropriately sized transducer for the body part being examined, at as high a frequency as possible, with the addition of both compound and harmonic imaging.

NORMAL FINDINGS IN CHILDREN

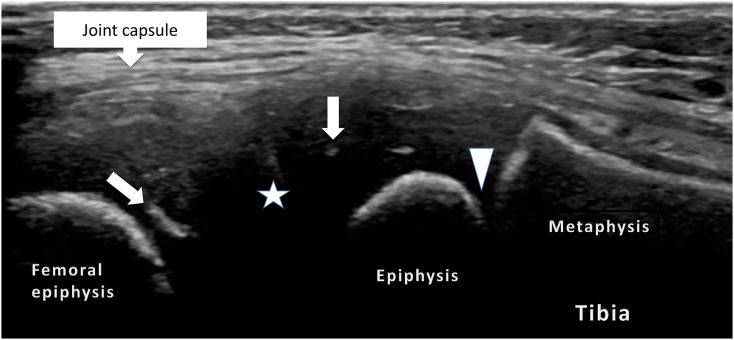

One of the most challenging aspects of paediatric MSK-US is differentiating normal from abnormal findings. Work carried out by Roth et al22 has provided the first ultrasound definitions of joints in healthy children (Table 3). The growing skeleton is composed of an initially cartilaginous epiphysis, physis (growth plate), metaphysis and diaphysis (Figure 3). The age at which ossification begins within the epiphysis varies depending on the individual bone involved, following (more or less) a well-described order,23 the discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article.

Table 3.

Consensus definitions of the normal findings within joints on ultrasound examination22

| Definition 1 | The hyaline cartilage will present as a well-defined anechoic structure (with/without bright echoes/dots) that is non-compressible. The cartilage surface can (but does not have to) be detected as a hyperechoic line |

| Definition 2 | With advancing maturity, the epiphyseal secondary ossification centre will appear as a hyperechoic structure, with a smooth or irregular surface within the cartilage |

| Definition 3 | Normal joint capsule—a hyperechoic structure that can (but does not have to) be seen over bone, cartilage and other intra-articular tissues of the joint |

| Definition 4 | Normal synovial membrane—under normal circumstances, the thin synovial membrane is undetectable |

| Definition 5 | The ossified portion of articular bone is detected as a hyperechoic line. Interruptions of this hyperechoic line may be detected at the growth plate and at the junction of two or more ossification centres |

Figure 3.

Lateral, longitudinal views of a normal knee joint: the image shows the potential joint space (star) lined by the hyaline cartilage and linear and radial echoes (arrows) representing vascular channels within the epiphyseal cartilage and the physeal cartilage (arrowhead).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no normal variant/normal developmental atlas for paediatric MSK-US, and therefore becoming familiar with the appearances at different ages is a large part of the learning curve when first contemplating performing these examinations.

Ultrasonographically, unossified cartilage, owing to its high water content appears hypoechoic. Internal radial linear echoes may be seen within the cartilaginous epiphysis, corresponding to blood vessels22 (Figure 3). The physis is also seen as a relatively linear, but undulating, hypoechoic structure (being unossified cartilage also); the metaphysis and diaphysis, being ossified, exhibit linear strongly reflective echoes. With increasing age, the chondroepiphysis begins ossification, initially a central reflective echo with posterior acoustic shadowing. This central echo is variable in appearance, but is frequently irregular in outline.22 Over time, the cartilaginous epiphysis is progressively mineralized until ultimately the whole epiphysis is ossified and covered by articular cartilage, which can be seen as a hypoechoic rim overlying the bone. The inexperienced practitioner should be aware of the possibility of mistaking this hypoechoic cartilage for joint fluid.

Establishing the range of normality in children is the key in standardising MSK-US and its use in JIA, because identifying disease impacts therapy. Spannow et al24 evaluated the normal range of articular cartilage thickness for a range of joints in healthy children, showing decreasing cartilage thickness with age in their cohort of 6–17-year olds, with males having thicker cartilage than females. A formula for calculating cartilage thickness according to age was also derived by Spannow et al, who suggest it may be used in monitoring responses to treatment.

When ultrasound-measured cartilage thickness is compared with MRI, good intermodality agreement was found with a difference of <0.5 mm, with good overall agreement with the exception of the wrist joint.25 An explanation for this may be the variability in ossification of the abundant cartilage found in the carpus.26 Unfortunately, cartilage thickness is also affected by confounding variables such as height, weight and skeletal maturation,24 likely making this a difficult parameter for clinical use.

MRI studies in healthy children have highlighted the presence of bony depressions that increase in number with age.27 Avenarius et al28 showed 75% of their healthy cohort had at least one cortical depression. The depressions are thought to represent sites of ligamentous insertion or vascular channels. In the clinical setting, knowledge of their presence is important, since they may be mistaken for erosions on ultrasound. The most accurate way to confirm a normal cortical depression is: (a) the anatomical location and (b) the presence of cartilage at its base, which would not be present in the eroded bone.

Another unique feature of normal paediatric hands and wrists is that on MRI, joint fluid is seen in at least one joint, with half of the children having >2 mm of fluid.29 Joint fluid is often used as a marker of disease in adults,29 but this clearly demonstrates that joint fluid alone cannot be used as a marker of JIA. Magni-Manzoni et al30 found ultrasound abnormalities in nearly 36% of healthy children including joint effusions, synovial hyperplasia and a single case of tenosynovitis. These are believed to be normal occurrences secondary to growth and development of the paediatric skeleton. Power Doppler (PD) signal has been reported as a common finding in the wrists of adults and children;18,31 these findings are more difficult to explain in adults but may be due to detection of normal nutrient vessels in children.32

ULTRASOUND FINDINGS IN JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

As ultrasound technology has advanced, its use in rheumatology has become widespread. One of the problems with ultrasound is that with technological improvements, practitioners are visualizing more without knowing the implications of these findings. For example, as PD becomes more sensitive to low flow, at what point is synovial vascularity abnormal? To begin filling this validity and reliability void, the outcome measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) ultrasound special interest group was formed in 2004. They developed the first consensus definitions for ultrasound pathologies in inflammatory joint diseases in adults. There are limited data in children, although work on B mode and Doppler ultrasound is currently under way.33 Ultrasound definitions of common lesions found in adult inflammatory arthritis (Table 4) were agreed upon in 2005 by the OMERACT group34 and are broadly adopted for use in children.

Table 4.

Consensus definitions of joint abnormalities in adult inflammatory arthritis as seen on ultrasound34

| Rheumatoid arthritis bone erosion | An intra-articular discontinuity of the bone surface that is visible in two perpendicular planes |

| Synovial fluid | Abnormal hypoechoic or anechoic (relative to subdermal fat, but sometimes may be isoechoic or hyperechoic) intra-articular material that is displaceable and compressible, but does not exhibit Doppler signal |

| Synovial hypertrophy | Abnormal hypoechoic (relative to subdermal fat, but sometimes may be isoechoic or hyperechoic) intra-articular tissue that is non-displaceable and poorly compressible and which may exhibit Doppler signal |

| Tenosynovitis | Hypoechoic or anechoic thickened tissue with or without fluid within the tendon sheath, which is seen in two perpendicular planes and which may exhibit Doppler signal |

| Enthesopathy | Abnormally hypoechoic (loss of normal fibrillar architecture) and/or thickened tendon or ligament at its bony attachment (may occasionally contain hyperechoic foci consistent with calcification), seen in two perpendicular planes that may exhibit Doppler signal and/or bony changes including enthesophytes, erosions or irregularity |

INFLAMMATORY CHANGES

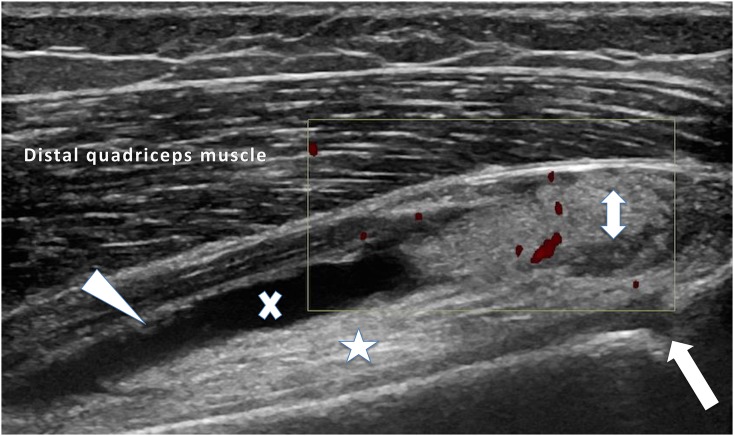

The primary pathology in JIA is centred on the synovium, and therefore synovial hypertrophy and hyperaemia are the primary sonographic correlates. Synovitis leads to synovial proliferation (Figure 4) and accumulation of inflammatory tissue (pannus), which is typically hypoechoic on B mode imaging. This is a potential pitfall for the inexperienced, as it may be misinterpreted as unossified cartilage, joint fluid (Figure 5) or effusion within a tendon sheath (Figure 6). Although typically low in reflectivity, synovial hypertrophy may also show mixed or increased echogenicity. There may be exudation of fluid accompanying synovitis. Such effusions are readily delineated on ultrasound, typically as hypoechoic collections, often, but not exclusively, in association with synovial thickening.

Figure 4.

An anterior longitudinal image of the suprapatella recess of the knee: active nodular synovitis (double-headed arrow) in the suprapatella recess and synovial thickening (arrowhead) in the visualized joint is shown. An anechoic joint effusion (x) is seen above the prefemoral fat pad (star), which was also hyperaemic (not shown). The unfused physis (arrow) is also demonstrated in this child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

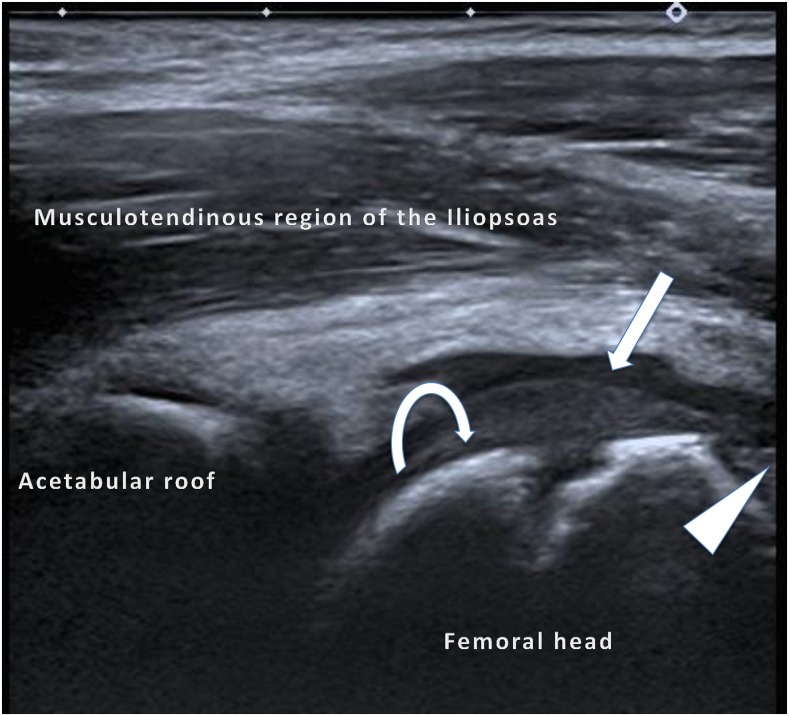

Figure 5.

An anterior longitudinal image of the hip joint: a mildly echogenic normal epiphyseal cartilage (curved arrow) is shown. When this is compared with the adjacent anechoic joint effusion (arrow), synovial proliferation is just visible at the femoral head–neck junction (arrowhead), which is similar in echogenicity to the unossified cartilage. Power Doppler interrogation of the synovium (not included) did not show any active synovitis.

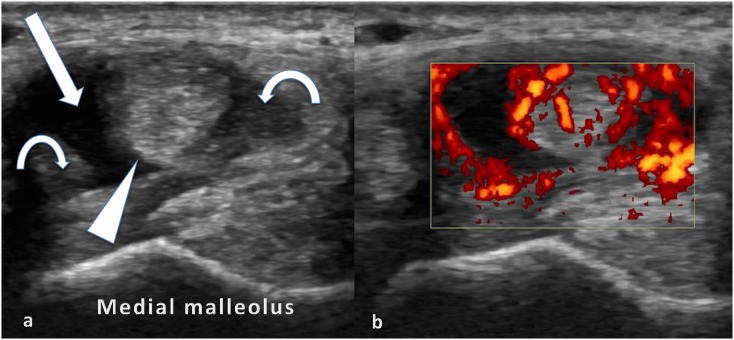

Figure 6.

Axial views of the medial ankle tendons in a patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the tibialis posterior tendon (arrowhead) surrounded by hypoechoic fluid (arrow) and mildly echogenic tenosynovitis (curved arrows) (a) and the power Doppler signal in keeping with active tenosynovitis (b).

One of the most useful contributions of ultrasound is not only delineating exactly which joints are involved, but also differentiating joint from tendon sheath involvement, which can be seen as increased tendon sheath thickness, tendon sheath effusions and hyperaemia (Figure 6). When examining superficial structures such as tendons, care must be taken with regard to the amount of pressure applied when performing ultrasound, as compression can displace tendon sheath effusions, deform synovial thickening and compress vessels, spuriously decreasing hyperaemia, all of which may lead to confusion. In such situations, the gel stand-off technique is useful. This is where a mound of gel is maintained between the probe and skin so as to apply minimum pressure to structures being evaluated.

Rooney et al35 observed that clinical differentiation of ankle joint swelling from ankle tenosynovitis is difficult. In their sample of 34 children who suffered from OJIA or PJIA, a total of 49 ankles were oedematous. Only 29% of ankles had a joint effusion alone on ultrasound, whereas 39% ankles had tenosynovitis alone and 71% ankles showed both joint synovitis and tenosynovitis. Interestingly, this study and a subsequent prospective study showed tibialis posterior involvement to be commoner in OJIA, and peroneal tenosynovitis to be commoner in PJIA.36 It has been postulated that the common coexistence of joint and tendon sheath synovitis may be due to the increased biomechanical stresses put upon tendons, as they cross and turn around joints such as the ankle. McGonagle37 suggested that these sites of stress should be considered as “functional entheses”, and this may account for the high prevalence of flexor tenosynovitis in psoriatic JIA.

Shenoy and Aggarwal37 have also shown that ultrasound has better sensitivity in detecting enthesitis than clinical examination in the form of increased vascularity on Doppler imaging. In a study of 27 patients with JIA, enthesitis was most commonly detected at the distal patella and Achilles tendon insertions with rare involvement of the plantar fascia. However, it remains difficult to interpret the validity of such changes on ultrasound, with up to 50% of all sites sonographically showing enthesitis being clinically normal in one study.38 In addition, enthesitis changes were not confined to enthesitis related Juvenile Idiopathic arthritis alone, being seen in patients with OJIA and PJIA.

DESTRUCTIVE CHANGES

Joint cartilage is a late target in arthritis, leading to joint space narrowing. High-frequency B mode ultrasound is suited to assessing the integrity of paediatric cartilage, being able to visualize the unossified physis as well as the articular cartilage contour.

In 2013, Pradsgaard et al39 performed cartilage measurements of five joints in patients with JIA and confirmed they had thinner cartilage than controls but also that JIA cases had significantly thinner cartilage regardless of whether the joints were previously affected by arthritis or not.

In 2015, investigators from the same group performed a validation study to confirm accurate measurements of the knee joint cartilage, with ultrasound using MRI as the reference standard.40 They identified the intercondylar notch of the distal femur of a flexed knee as the easiest site for reproducibility and confirmed good reliability. Given the good reliability of cartilage assessment by ultrasound, there is a prospect that examination of the knee with ultrasound could be used as a marker of disease activity.

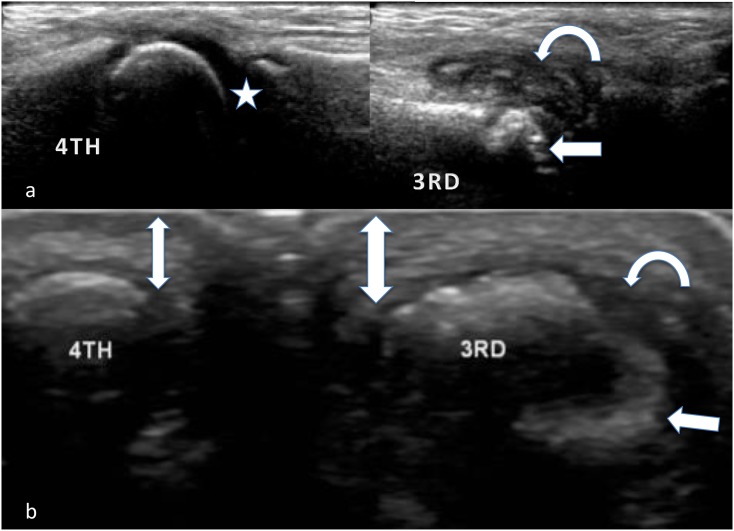

As cartilage is degraded by joint inflammation, there is exposure of the underlying subchondral bone, which, if unchecked, goes on to become eroded (Figure 7). Since ultrasound is dynamic, it is possible to examine symptomatic joints in several planes, potentially visualizing erosions that would have gone unnoticed on plain radiographs. It is known that erosions are more common in females, patients with PJIA, early disease onset, with elevated inflammatory markers and if rheumatoid factor is positive.41 Ultrasound practitioners should be aware of the potential pitfalls when assessing for cortical erosions that include physiological irregularities such as secondary ossification centres, cortical depressions, growth plates at the epiphyseal cartilage and newly ossifying bone.

Figure 7.

Longitudinal (a) and axial (b) images of a damaged third and normal fourth metacarpophalangeal joint in a patient with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the preserved chondroepiphysis and hyaline cartilage (star) as compared with the deformed third metacarpal head, which contains erosions (arrows), synovial thickening/pannus (curved arrows) and oedema in the soft tissues (thick double-headed arrow), blurring boundaries between the normal tissue layers (thin double-sided arrow), can be noted.

Ultrasound has a limited role in depicting growth deformities, which are better evaluated by modalities that provide more global assessment.

DISEASE ACTIVITY ASSESSMENT AND COMPARISON WITH CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

In adults, disease activity has traditionally been assessed upon clinical and serological markers. Current criteria to assess disease remission in adults are based on the “modified Wallace criteria”,42 which does not include imaging. Given the increased periarticular soft tissue, potential compliance difficulties in examining children and reluctance to routinely take blood samples, this is more of a challenge in JIA.

Ultrasound has therefore been suggested as a means of evaluating disease activity in JIA.20 Shahin et al43 and others have shown an association with circulating Interleukin 6 (amongst other cytokines) and the amount of joint vascularity demonstrated on PD. Colour and PD techniques can potentially be used in addition to B mode imaging to assess synovitis and thus disease activity.

Using a combination of synovial thickening, effusion and vascularity, it has been shown that ultrasound is more sensitive for the detection of disease-affected joints in JIA and detects a greater number of involved joints than physical examination.19,32,44 Imaging only-detected disease activity or subclinical synovitis has been shown to correlate with progression of joint damage in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).45 Magni-Manzoni et al30 showed that although subclinical synovitis in their cohort of 39 children was common (77%), 67% of children remained in clinical remission after 2 years, concluding that subclinical synovitis does not predict subsequent flare. Given the complexity of JIA and its subtypes, the significance of subclinical synovitis in JIA remains undetermined.

There are other important issues raised by subclinical synovitis, as the number of disease involved joints influences not only the diagnosis (e.g. OJIA or PJIA) but also treatment decisions, in particular whether or not to institute biologic agents.14,46,47

Historically, disease follow-up has been performed using JIA-specific scoring systems based on conventional radiographs.48 It has been shown that ultrasound can be reliably used to assess cartilage thickness, synovitis and joint effusions. Although MRI is superior, ultrasound is at least as good if not better than plain radiography for detection of cortical erosions in accessible regions.49 Semi-quantitative scoring systems have been applied to only adults with RA where PD signal in synovitis showed good correlation with histopathology and intraoperative appearances.50

Ultrasound can locate the anatomical abnormality and guide injection of intra-articular steroid with reduced rates of complications such as subcutaneous atrophy. On follow-up, ultrasound can demonstrate normalization or regression of hyperaemia and synovial hypertrophy.20,51 Similar findings have been shown when ultrasound is used to follow up disease response to antirheumatic drugs52 and biologic therapies53 in adults.

FUTURE OF ULTRASOUND IMAGING IN JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

Ultrasound imaging has advanced rapidly in the past 10 years with improvements in software and hardware. Near-field imaging as used in the majority of rheumatological indications has seen use of higher frequency probes with resolution up to 0.1 mm.54 The sensitivity of colour Doppler has increased with manufacturers claiming it to be more sensitive to low flow than PD.55

Colour and PD have a limited sensitivity in detecting the neomicrovascularity of synovitis, the detection of which may be increased by performing i.v. microbubble contrast-enhanced ultrasound to depict synovial enhancement. Time–intensity curves could provide an objective measure of vascularity and hence inflammation which could be useful in grading disease severity and response to treatment.56 Unfortunately, the requirement for peripheral venous access and limited standardization make this technique less attractive in the general outpatient paediatric population.

Conventional two-dimensional ultrasound imaging visualizes a limited slice of anatomy; however, three-dimensional imaging can depict a whole joint. Using post-processing software, computerized quantification of proliferative synovitis can be obtained, as has been shown in synovitic knees.57 Three-dimensional ultrasound has not reached routine clinical practice because its resolution remains poorer than that of B mode and Doppler imaging.

Real-time elastography has been shown to demonstrate that degenerative tendons are softer than healthy tendon. This has gained much interest in the evaluation of lateral epicondylitis and Achilles tendinopathy,58 and conceivably there may be a role in detecting enthesitis which could be considered as the inflammatory homologue of “overuse” enthesitis.

Fusion imaging superimposes cross-sectional imaging data onto real-time ultrasound imaging. It is already in use in nuclear medicine, radiotherapy and neurosurgery. The system uses an electromagnetic field around the patient. A small receiver on the ultrasound probe provides information about position and orientation. As the probe moves, the magnitude of electrical current in the sensor changes within the magnetic field enabling the sensor unit to locate the transducer. Images are displayed by extracting CT or MRI slices at the location parallel to the ultrasound beam.59,60 Potential applications include ultrasound-guided injections into difficult-to-access regions such as the sacroiliac joints with real-time needle placement on previously acquired cross-sectional data, thereby limiting radiation exposure in the CT or fluoroscopy suite.60

As described above, several advanced ultrasound applications have potential use in JIA imaging but require further investigation before these can be clinically implemented.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the literature supports the use of ultrasound in JIA but with the proviso that practitioners should be aware of the complex anatomy that can demonstrate a wide range of normal findings including “joint abnormalities” that are also detectable in healthy children. Evidence shows ultrasound to be superior to the clinical examination alone, but the lack of validated sonographic findings, scoring systems and treatment algorithms exposes the need for further research. Initial steps should include addressing the sonographic definitions of the normal paediatric joint and validating ultrasound protocols used in evaluating juvenile arthritis.

Contributor Information

Hershernpal A S Basra, Email: h.basra@nhs.net.

Paul D Humphries, Email: paul.humphries@gosh.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Thierry S, Fautrel B, Lemelle I, Guillemin F. Prevalence and incidence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review. Joint Bone Spine 2014; 81: 112–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, He X, et al. International league of associations for rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001; 31. [PubMed]

- 3.Rigante D, Bosco A, Esposito S. The etiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2015; 49: 253–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-014-8460-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgos-Vargas R. Juvenile onset spondyloarthropathies: therapeutic aspects. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61(Suppl. 3): 33–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martini A. Are the number of joints involved or the presence of psoriasis still useful tools to identify homogeneous disease entities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis? J Rheumatol 2003; 30: 1900–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prahalad S. Genetic analysis of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: approaches to complex traits. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2006; 36: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray KJ, Moroldo MB, Donnelly P, Prahalad S, Passo MH, Giannini EH, et al. AGE-specific effects of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis–associated HLA alleles. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42: 1843–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandborg C, Mellins ED. A new era in the treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 2439–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1212640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mellins ED, Macaubas C, Grom AA. Pathogenesis of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: some answers, more questions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011; 7: 416–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2011.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masters SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27: 621–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Wallace C. Judicious use of biologicals in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16: 454. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-014-0454-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backhaus M, Kamradt T, Sandrock D, Loreck D, Fritz J, Wolf KJ, et al. Arthritis of the finger joints: a comprehensive approach comparing conventional radiography, scintigraphy, ultrasound, and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42: 1232–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Damasio MB, Malattia C, Martini A, Tomá P. Synovial and inflammatory diseases in childhood: role of new imaging modalities in the assessment of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Radiol 2010; 40: 985–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-010-1612-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovell DJ, Giannini EH, Reiff A, Cawkwell GD, Silverman ED, Nocton JJ, et al. Etanercept in children with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 763–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200003163421103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince FH, Otten MH, Suijlekom-Smit LW. Diagnosis and management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. BMJ 2010; 341: c6434. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c6434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damasio MB, de Horatio LT, Boavida P, Lambot-Juhan K, Rosendahl K, Tomà P, et al. Imaging in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): an update with particular emphasis on MRI. Acta Radiol 2013; 54: 1015–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erik Nielsen H, Strandberg C, Andersen S, Kinnander C, Erichsen G. Ultrasonographic examination in juvenile idiopathic arthritis is better than clinical examination for identification of intraarticular disease. Dan Med J 2013; 60: 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magni-Manzoni S, Epis O, Ravelli A, Klersy C, Visconti C, Lanni S, et al. Comparison of clinical versus ultrasound-determined synovitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2009; 61: 1497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haslam KE, McCann LJ, Wyatt S, Wakefield RJ. The detection of subclinical synovitis by ultrasound in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a pilot study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49: 123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurell L, Court-Payen M, Nielsen S, Zak M, Boesen M, Fasth A. Ultrasonography and color Doppler in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and follow-up of ultrasound-guided steroid injection in the ankle region. A descriptive interventional study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2011; 9: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin DC, Nazarian LN, O'Kane PL, McShane JM, Parker L, Merritt CR. Advantages of real-time spatial compound sonography of the musculoskeletal system versus conventional sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002; 179: 1629–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth J, Jousse-Joulin S, Magni-Manzoni S, Rodriguez A, Tzaribachev N, Iagnocco A, et al. Definitions for the sonographic features of joints in healthy children. Arthritis Care Res 2015; 67: 136–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham CB. Assessment of bone maturation—methods and pitfalls. Radiol Clin North Am 1972; 10: 185–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spannow AH, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Andersen NT, Herlin T, Stenbøg E. Ultrasonographic measurements of joint cartilage thickness in healthy children: age- and sex-related standard reference values. J Rheumatol 2010; 37: 2595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spannow AH, Stenboeg E, Pfeiffer-Jensen M, Fiirgaard B, Haislund M, Ostergaard M, et al. Ultrasound and MRI measurements of joint cartilage in healthy children: a validation study. Ultraschall Med 2011; 32(Suppl. 1): S110–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1245374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanni S, Wood M, Ravelli A, Magni Manzoni S, Emery P, Wakefield RJ. Towards a role of ultrasound in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013; 52: 413–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kes287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avenarius DM, Ording Müller LS, Eldevik P, Owens CM, Rosendahl K. The paediatric wrist revisited-findings of bony depressions in healthy children on radiographs compared to MRI. Pediatr Radiol 2012; 42: 791–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avenarius DF, Ording Müller LS, Rosendahl K. Erosion or normal variant? 4-year MRI follow-up of the wrists in healthy children. Pediatr Radiol 2016; 46: 322–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-015-3494-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Müller LS, Avenarius D, Damasio B, Eldevik OP, Malattia C, Lambot-Juhan K, et al. The paediatric wrist revisited: redefining MR findings in healthy children. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 605–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Magni-Manzoni S, Scirè CA, Ravelli A, Klersy C, Rossi S, Muratore V, et al. Ultrasound-detected synovial abnormalities are frequent in clinically inactive juvenile idiopathic arthritis, but do not predict a flare of synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terslev L, Torp-Pedersen S, Qvistgaard E, von der Recke P, Bliddal H. Doppler ultrasound findings in healthy wrists and finger joints. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 644–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2003.009548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miotto Silva BV, De Freitas Tavares da Silva C, De Aguiar Vilela Mitraud S, Vilar Furtado NR, Esteves Hilário MO, Natour J, et al. Do patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in remission exhibit active synovitis on joint ultrasound? Rheumatol Int 2014; 34: 937–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruyn GA, Naredo E, Iagnocco A, Balint PV, Backhaus M, Gandjbakhch F, et al. The OMERACT ultrasound working group 10 years on: update at OMERACT 12. J Rheumatol 2015; 42: 2172–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.141462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakefield RJ, Balint PV, Szkudlarek M, Filippucci E, Backhaus M, D'Agostino MA, et al. Musculoskeletal ultrasound including definitions for ultrasonographic pathology. J Rheumatol 2005; 32: 2485–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rooney ME, McAllister C, Burns JF. Ankle disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: ultrasound findings in clinically swollen ankles. J Rheumatol 2009; 36: 1725–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pascoli L, Wright S, McAllister C, Rooney M. Prospective evaluation of clinical and ultrasound findings in ankle disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Importance of ankle ultrasound. J Rheumatol 2010; 37: 2409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shenoy S, Aggarwal A. Sonologic enthesitis in children with enthesitis-related arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016; 34: 143–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jousse-Joulin S, Breton S, Cangemi C, Fenoll B, Bressolette L, De Parscau L, et al. Ultrasonography for detecting enthesitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63: 849–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pradsgaard DO, Spannow AH, Heuck C, Herlin T. Decreased cartilage thickness in juvenile idiopathic arthritis assessed by ultrasonography. J Rheumatol 2013; 40: 1596–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pradsgaard DO, Fiirgaard B, Spannow AH, Heuck C, Herlin T. Cartilage thickness of the knee joint in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: comparative assessment by ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Rheumatol 2015; 42: 534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adib N, Silman A, Thomson W. Outcome following onset of juvenile idiopathic inflammatory arthritis: II. Predictors of outcome in juvenile arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005; 44: 1002–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keh621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Huang B, Itert L, Ruperto N. American College of Rheumatology provisional criteria for defining clinical inactive disease in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63: 929–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shahin AA, Shaker OG, Kamal N, Hafez HA, Gaber W, Shahin HA. Circulating interleukin-6, soluble interleukin-2 receptors, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-10 levels in juvenile chronic arthritis: correlations with soft tissue vascularity assessed by power Doppler sonography. Rheumatol Int 2002; 22: 84–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Janow GL, Panghaal V, Trinh A, Badger D, Levin TL, Ilowite NT. Detection of active disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: sensitivity and specificity of the physical examination vs ultrasound. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 2671–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown AK, Conaghan PG, Karim Z, Quinn MA, Ikeda K, Peterfy CG, et al. An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 2958–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruperto N, Murray KJ, Gerloni V, Wulffraat N, de Oliveira SK, Falcini F, et al. A randomized trial of parenteral methotrexate comparing an intermediate dose with a higher dose in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who failed to respond to standard doses of methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 2191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, Reiff A, Jung L, Jarosova K, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 810–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0706290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ravelli A, Ioseliani M, Norambuena X, Sato J, Pistorio A, Rossi F, et al. Adapted versions of the Sharp/van der Heijde score are reliable and valid for assessment of radiographic progression in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56: 3087–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malattia C, Damasio MB, Magnaguagno F, Pistorio A, Valle M, Martinoli C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasonography, and conventional radiography in the assessment of bone erosions in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59: 1764–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walther M, Harms H, Krenn V, Radke S, Faehndrich TP, Gohlke F. Correlation of power Doppler sonography with vascularity of the synovial tissue of the knee joint in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001; 44: 331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laurell L, Court-Payen M, Nielsen S, Zak M, Fasth A. Ultrasonography and color Doppler in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and follow-up of ultrasound-guided steroid injection in the wrist region. A descriptive interventional study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2012; 10: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naredo E, Collado P, Cruz A, Palop MJ, Cabero F, Richi P, et al. Longitudinal power Doppler ultrasonographic assessment of joint inflammatory activity in early rheumatoid arthritis: predictive value in disease activity and radiologic progression. Arthritis Care Res 2007; 57: 116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziswiler HR, Aeberli D, Villiger PM, Möller B. High-resolution ultrasound confirms reduced synovial hyperplasia following rituximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2009; 48: 939–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bedi T, Bagga R. Ultrasound in rheumatology. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2007; 17: 299–305. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torp-Pedersen ST, Terslev L. Settings and artefacts relevant in colour/power Doppler ultrasound in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 143–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2007.078451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rednic N, Tamas MM, Rednic S. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in inflammatory arthritis. Med Ultrason 2011; 13: 220–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ju JH, Kang KY, Kim IJ, Yoon JU, Kim HY, Park SH. Three-dimensional ultrasonographic application for analyzing synovial hypertrophy of the knee in patients with osteoarthritis. J Ultrasound Med 2008; 27: 729–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Zordo T, Lill SR, Fink C, Feuchtner GM, Jaschke W, Bellmann-Weiler R, et al. Real-time sonoelastography of lateral epicondylitis: comparison of findings between patients and healthy volunteers. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193: 180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee MW. Fusion imaging of real-time ultrasonography with CT or MRI for hepatic intervention. Ultrasonography 2014; 33: 227–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.14366/usg.14021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klauser AS, Peetrons P. Developments in musculoskeletal ultrasound and clinical applications. Skeletal Radiol 2010; 39: 1061–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-009-0782-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]