Abstract

Toxin-antitoxin systems are ubiquitous in prokaryotic and archaeal genomes and regulate growth in response to stress. Escherichia coli contains at least 36 putative toxin-antitoxin gene pairs, and some pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis have over 90 toxin-antitoxin operons. E. coli MazF cleaves free mRNA after encountering stress, and nine M. tuberculosis MazF family members cleave mRNA, tRNA, or rRNA. Moreover, M. tuberculosis MazF-mt6 cleaves 23S rRNA Helix 70 to inhibit protein synthesis. The overall tertiary folds of these MazFs are predicted to be similar, and therefore, it is unclear how they recognize structurally distinct RNAs. Here we report the 2.7-Å X-ray crystal structure of MazF-mt6. MazF-mt6 adopts a PemK-like fold but lacks an elongated β1-β2 linker, a region that typically acts as a gate to direct RNA or antitoxin binding. In the absence of an elongated β1-β2 linker, MazF-mt6 is unable to transition between open and closed states, suggesting that the regulation of RNA or antitoxin selection may be distinct from other canonical MazFs. Additionally, a shortened β1-β2 linker allows for the formation of a deep, solvent-accessible, active-site pocket, which may allow recognition of specific, structured RNAs like Helix 70. Structure-based mutagenesis and bacterial growth assays demonstrate that MazF-mt6 residues Asp-10, Arg-13, and Thr-36 are critical for RNase activity and likely catalyze the proton-relay mechanism for RNA cleavage. These results provide further critical insights into how MazF secondary structural elements adapt to recognize diverse RNA substrates.

Keywords: bacterial toxin, endoribonuclease, protein synthesis, ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) (ribosomal RNA), ribosome, X-ray crystallography

Introduction

Toxin-antitoxin complexes are two-component operons distributed widely among prokaryotic and archaeal genomes where they have diverse roles in bacterial physiology. These small gene pairs are critical for postsegregational killing, adaptive responses to environmental stress, antibiotic tolerance, and host-pathogen virulence responses (1, 2). Toxin-antitoxins are organized into six different classes based on how the antitoxin component regulates toxin activity (3). In all classes, the toxin is proteinaceous and inhibits an essential cellular function such as replication, translation, or an assembly pathway including ribosome and membrane biogenesis in response to stress (2, 4). The antitoxin is either RNA or protein that inhibits toxin activity by direct binding (Types II, III, and VI), preventing toxin protein expression (Types I and V), or competing with the toxin for substrate binding (Type IV) (3).

Type II toxin-antitoxin complexes are the most abundant and best characterized toxin-antitoxin systems (5). In this type, the antitoxin protein neutralizes the toxin protein by direct binding. Most Type II toxins are endoribonucleases and are either ribosome-dependent or -independent. Ribosome-dependent toxins such as Escherichia coli RelE, YoeB, and YafQ and Proteus vulgaris HigB cleave mRNA but only when bound to the ribosome (6–8). In contrast, E. coli and Bacillus subtilis MazFs are endoribonucleases that degrade free mRNAs at sequences containing 5′-N↓ACA-3′ and 5′-U↓ACAU-3′, respectively (arrow denoting cleavage) (9, 10). The Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome contains more than 90 putative toxin-antitoxin operons with nine MazEF paralogues (annotated as mt1–mt9) (5). Three of the nine MazF toxins (MazF-mt3, MazF-mt6, and MazF-mt9) cause growth arrest when overexpressed in E. coli (11). Surprisingly, in addition to cleaving mRNAs, M. tuberculosis MazF toxins cleave different RNAs that are structurally distinct. For example, MazF-mt9 cleaves tRNAs, MazF-mt6 cleaves 23S rRNA, and MazF-mt3 cleaves both 16S and 23S rRNA, all resulting in the inhibition of protein synthesis (12–14). Although the overall tertiary fold of these MazFs are predicted to be similar (13), it is unclear how they then recognize very structurally different RNAs.

MazF-mt6 toxin cleaves 23S rRNA at Helix 70 (H70)2 of the large 50S subunit at a consensus sequence of 5-1939UU↓CCU1943-3′ (13). H70 is at the interface between the 30S and 50S subunits and adopts a 10-nucleotide (nt) stem-loop with the consensus sequence located in an internal bulged region. Here, we solved the 2.7-Å X-ray crystal structure of MtbMazF-mt6 and show that MazF-mt6 adopts a plasmid emergency maintenance K (PemK)-like fold, an architecture commonly adopted by several bacterial toxins including PemK and CcdB (15). MazF-mt6 contains a significantly shorter β1-β2 linker, the region predicted to interact with RNA (13). We found that MazF-mt6 cleaves a 35-mer H70 RNA, strongly suggesting that the entire 23S rRNA is not required for MazF-mt6 activity. We further determined that MazF-mt6 residues Asp-10, Arg-13, and Thr-36 are critical for activity and likely perform mRNA cleavage via a proton relay mechanism. These data provide a structural and functional framework for how MazF endoribonucleases recognize diverse RNA substrates by the remodeling of loops to mediate RNA recognition.

Results

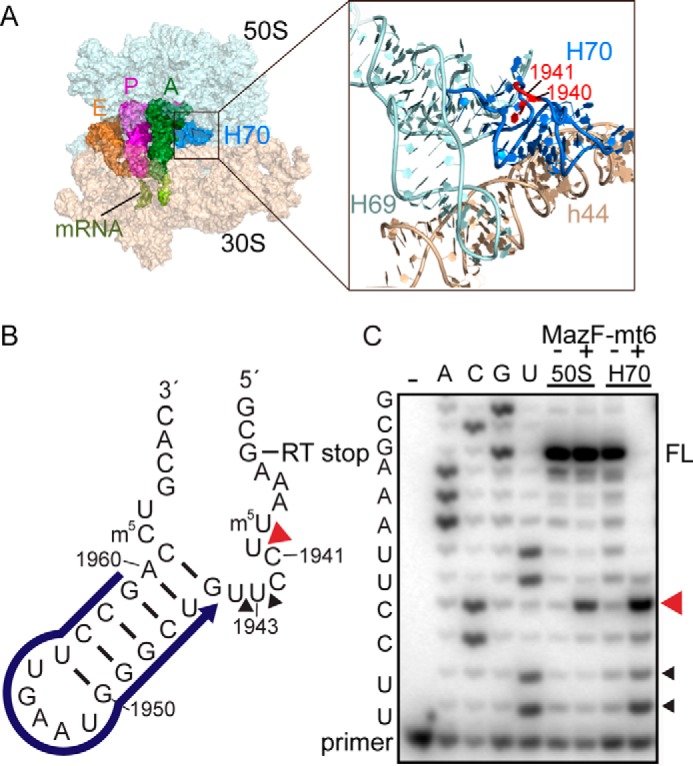

MazF-mt6 cleaves both 23S rRNA and H70

MazF-mt6 inhibits protein synthesis by cleaving the 23S rRNA at H70 (1939UU↓CCU1943), an RNA sequence conserved between M. tuberculosis and E. coli 70S (13). H70 forms interactions with the A-site tRNA and ribosome recycling factor during elongation and interacts directly with 16S rRNA decoding helix 44 (Fig. 1A) (16, 17). To test for activity, we incubated MazF-mt6 with purified E. coli 50S and monitored 23S rRNA cleavage product formation using reverse transcription (RT) from a complementary DNA oligo annealed to 23S rRNA nt 1959–1945 (Fig. 1B). We used a poisoned RT reaction that yields full-length and cleaved products of 19 and 25 nt, respectively (18). The extension is halted by incorporating dideoxy-CTP at position 1935, 6 nt after the cleavage site. Using this experimental setup, we confirmed that MazF-mt6 primarily cleaves between residues 1940 and 1941 (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S1). We next tested whether MazF-mt6 required an intact 50S by incubating MazF-mt6 with a 35-nt RNA containing the H70 sequence (nt 1933–1967) (Fig. 1B). The major RT product is 11 nt, corresponding to cleavage between 1940 and 1941 (64% of the product formed), as demonstrated previously (13). However, there are additional minor RT products corresponding to cleavage after C1942 and U1943 in the same bulged loop (8 and 23%, respectively; Fig. 1C). Although MazF-mt6 cleaves H70 almost to completion, MazF-mt6 only cleaves 23S rRNA in the 50S to ∼30% completion.

Figure 1.

Location of 23S rRNA Helix 70 in the context of the ribosome. A, overview of the 70S containing A-site, P-site, and E-site tRNAs (PDB code 4Y4R) (left panel). An expanded view of 23S rRNA Helix 69 (H69) and H70 and 16S rRNA helix 44 (h44) is shown in the right panel. H70 residues that MazF-mt6 targets are shown in red. B) H70 (nucleotide positions 1933–1967) indicating the location of the RT primer (blue), MazF-mt6 cleavage site (red arrowhead), and RT stop at nucleotide 1935. C, RT assays demonstrating MazF-mt6-induced 23S rRNA or H70 cleavage. The cleavage products were monitored by RT, and the reactions were run on an 8 m urea polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The MazF-mt6 full-length RT stop (FL), the major cleavage site (red arrowhead), and a minor cleavage site (black arrowhead) are indicated.

Structure determination of MazF-mt6

MazF-mt6 was overexpressed and purified fused to an N-terminal hexahistidine (His6)-trigger factor (TF) as described previously (13). In addition to immobilized metal affinity chromatography purification, the His6-TF-MazF-mt6 complex was incubated with thrombin protease to release TF. MazF-mt6 was further purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex S200, GE Healthcare) and concentrated to 10 mg/ml. Crystals formed in the P6422 space group with two identical, symmetry-related MazF monomers in the asymmetric unit. The X-ray crystal structure was solved to 2.7-Å resolution by molecular replacement using B. subtilis MazF (BsMazF) as a search model in the Phaser program of the PHENIX suite (Table 1 and Fig. 2; Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 4MDX) (19, 20). The MazF-mt6 model was manually built in the Crystallographic Object-Oriented Toolkit program (Coot), and geometry and B-factor refinements in PHENIX and rebuilding in Coot were iteratively performed (20, 21). The final model contains residues 2–99 (of 103 total residues).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| MazF-mt6 | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P 6422 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97920 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 105.2, 105.2, 144.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 77.0–2.70 |

| Rp.i.m. (%) | 3.37 (53.1)a |

| I/σI | 12 (1.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 95 (99) |

| Redundancy | 6.3 (6.5) |

| CC1/2 (%) | 99.8 (66.2) |

| Refinement | |

| Reflections | 13,309 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 23.3/25.2 |

| No. atoms | |

| Macromolecule | 1,540 |

| Ligand/ion | 20 |

| Water | 5 |

| B-factors (Å2) | |

| Overall | 84.9 |

| Macromolecule | 84.3 |

| Ligand/ion | 132 |

| r.m.s.b deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.12 |

a Highest resolution shell is shown in parentheses.

b r.m.s., root mean square.

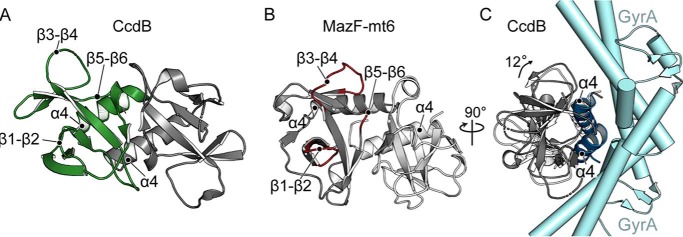

Figure 2.

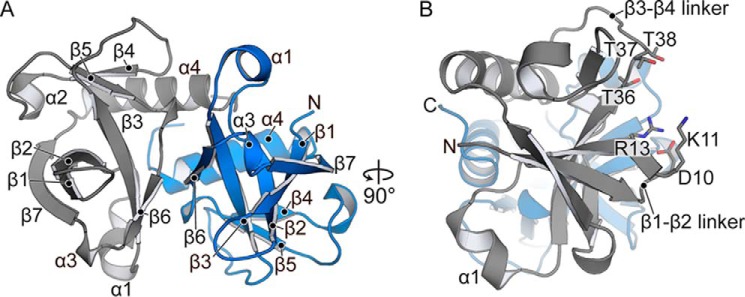

Structure of M. tuberculosis MazF-mt6. A, the MazF-mt6 is a homodimer consisting of seven β-strands and four α-helices. B, A 90° rotated view to show the SH3-like antiparallel β-sheet and the proximity of the active-site residue location on the β1-β2 and β3-β4 linkers.

MazF-mt6 adopts a PemK-like ribonuclease fold

MazF-mt6 is a small globular protein (10.8 kDa) consisting of two β-sheets and three α-helices. One β-sheet adopts a five-stranded, antiparallel SH3-like barrel fold (β7↑β1↓β2↓β3↑β6↓) linked by four small α-helices (α1, α2, α3, and α4), whereas the second β-sheet is three-stranded and antiparallel (β4↓β5↑) connected to a large C-terminal α-helix (α4) (22) (Fig. 2A). Although MazF-mt6 shares low amino acid sequence identity with orthologous family members (15–28%) (supplemental Fig. S2), MazF-mt6 adopts a PemK-like fold as seen in other bacterial toxins including E. coli CcdB, MazF, and PemK (23–27). A DALI search (28) reveals that MazF-mt6 shares high structural homology with Staphylococcus aureus MazF (PDB code 4MZP; root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) = 1.4 Å, Z = 15.7), BsMazF toxin (PDB code 4MDX; r.m.s.d. = 1.4 Å, Z = 15.5), E. coli MazF toxin (EcMazF; PDB code 5CR2; r.m.s.d. = 1.9 Å, Z = 12.6), Bacillus anthracis MoxT toxin (PDB code 4HKE; r.m.s.d. = 1.4 Å, Z = 15.3), E. coli CcdB toxin (PDB code 2VUB; r.m.s.d. = 2.3 Å, Z = 12.9), and E. coli Kid toxin (PDB code 1M1F; r.m.s.d. = 2.0 Å, Z = 11.8). Dimerization of MazF-mt6 is mediated by C-terminal α4-α4 interactions similar to BsMazF (19, 29) (Fig. 2A). MazF-mt6 dimerization buries ∼2,000 Å2 of hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between β6 and α4 in comparison with other MazFs that have an additional 500 Å2 buried.

Sequence alignments of MazF-mt6 with BsMazF and EcMazF (referred to as MazF hereafter) reveal RNA-binding regions that differ in length (19). Comparison of the structure of MazF-mt6 with MazFs that interact with mRNA reveals that MazF-mt6 contains a significantly shorter β1-β2 linker, the region that interacts with mRNA (19, 29) (Fig. 2B). The MazF β1-β2 linker is 13 residues in length, whereas in MazF-mt6, β1-β2 linker is only five residues. The MazF β1-β2 linker extends ∼10 Å from one monomer to the other monomer, forming part of the dimer interface that packs against and covers a net positive charge where mRNA binds (19). Because there is a shortened MazF-mt6 β1-β2 linker, this region does not extend toward the dimer interface, leaving the positively charged cleft exposed. An additional positive region is exposed upon MazE antitoxin binding (19, 29). This second positively charged region is missing in MazF-mt6, and instead a negative solvent-exposed patch is present.

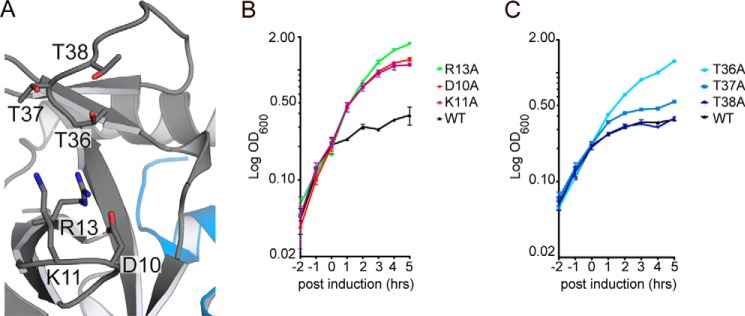

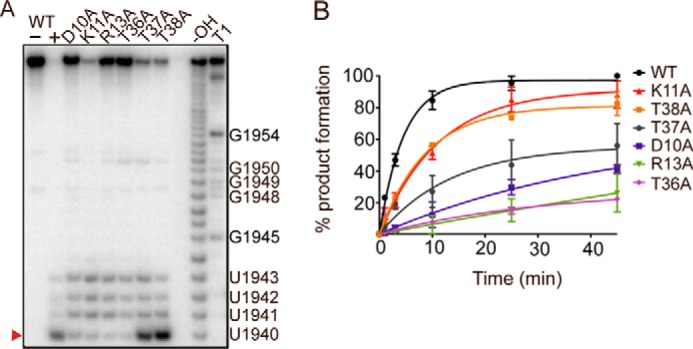

MazF-mt6 residues Asp-10, Arg-13, and Thr-36 are important for activity and inhibition of bacterial growth

The MazF-mt6 structure reveals that residues Asp-10, Lys-11, Arg-13, Thr-36, Thr-37, and Thr-38 are adjacent to the putative active site, which also contains a bound sulfate ion (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S3). The negatively charged sulfate ion can mimic the phosphate backbone of RNA and provides further support that this location is likely the active site. To identify which MazF-mt6 residues are important for toxin activity, we used an established cell-based assay whereby overexpression of wild-type (WT) MazF-mt6 inhibits growth (11, 30). MazF-mt6 variants that restore growth are interpreted as disrupting canonical MazF-mt6 function. As demonstrated previously, overexpression of WT MazF-mt6 inhibits cell growth in E. coli, whereas uninduced or vector control only exhibits normal growth (supplemental Fig. S4) (19). MazF residues previously identified as important for activity include an arginine that functions as both an acid and a base and either a serine or threonine that stabilizes the transition state during mRNA cleavage (19, 29, 31). MazF-mt6 residue Arg-13 is located on the shortened β1-β2 linker in a similar location as catalytic residues EcMazF Arg-29 and BsMazF Arg-25. Expression of MazF-mt6 R13A variant allows for normal growth, demonstrating that this residue is important for activity (Fig. 3B). Proximal residues to the MazF-mt6 active site include Asp-10 and Lys-11. Expression of the MazF-mt6 D10A and K11A variants allow for growth, suggesting that these residues have a critical role in activity (Fig. 3B). MazF-mt6 contains three threonine residues adjacent to its active site, suggesting that each could potentially stabilize the transition state. We found that the T38A variant has no effect on MazF-mt6 inhibition of growth, whereas the T37A variant has a modest growth effect (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the T36A variant causes a reversal of growth inhibition, suggesting that Thr-36 plays a critical role in MazF-mt6 activity.

Figure 3.

MazF-mt6 residues important for activity. A, MazF-mt6 putative active site highlighting the residues that were targeted for single variant analysis. B and C, E. coli BW25113 growth monitored over 5 h postinduction of WT MazF-mt6 and active-site variants. Cells were grown in M9 medium supplemented with 0.2% glycerol and 0.2% casamino acids, and induction was initiated by the addition of 0.2% arabinose after cells reached an optical density of 0.2 at 600 nm. Error bars represent standard error of means from three independent experiments.

MazF-mt6 residues Asp-10, Arg-13, and Thr-36 have the largest impact on rRNA degradation

Bacterial growth assays suggested that MazF-mt6 residues Asp-10, Arg-13, Thr-36, and possibly Lys-11 are important for endoribonuclease activity (Fig. 3). To assess the quantitative impact each MazF-mt6 residue has on mRNA cleavage, we performed single turnover assays where 5′-32P-labeled H70 RNA was incubated with a 10-fold molar excess of MazF-mt6 over a time course of 45 min (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S5). The cleavage of H70 by WT MazF-mt6 was monitored by the accumulation of RNA products corresponding to 8–11 nt. The major product for WT MazF-mt6 cleavage was an RNA product corresponding to cleavage between U1940 and C1941 (3.7 × 10−3 s−1) (Table 2). MazF-mt6 variants R13A and T36A had the most significant impact on activity with minimal RNA cleavage products detected (Fig. 4A). In contrast, MazF-mt6 variants K11A, T37A, and T38A had minor effects on RNA cleavage as compared with WT, suggesting that although these residues are proximal to the active site they do not contribute substantially to catalysis. Although the K11A variant appeared to have a large effect on activity in the bacterial growth assays (Fig. 3B), the variant has a minimal effect on activity in single turnover experiments. These data suggest that the K11A variant either has impaired RNA binding or lower protein solubility, which could reduce its expression in the cell-based assays. MazF-mt6 residue Asp-10 is adjacent to critical residue Arg-13. The MazF-mt6 D10A variant decreased the rate of RNA cleavage by 10-fold (4 × 10−4 s−1), suggesting that this residue is important for catalysis (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

MazF-mt6 residues Asp-10, Arg-13, and Thr-36 are critical for endonuclease activity. A, single-turnover experiments monitoring H70 cleavage by WT MazF-mt6 and MazF-mt6 variants. The products were analyzed on an 8 m urea polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The major cleavage product is denoted with a red arrowhead at U1940, and other minor cleavage products are indicated at positions 1941–1943. B, the product progression plot of WT MazF-mt6 and MazF-mt6 variants as monitored over a time course of 45 min. Error bars represent standard error of means from two independent experiments.

Table 2.

Effects MazF-mt6 variants have on RNA cleavage

| MazF-mt6 variant | Kobs |

|---|---|

| s−1 | |

| Wild type | 3.5 × 10−3 ± 2 × 10−4 |

| D10A | 2.53 × 10−4 ± 2 × 10−5 |

| K11A | 8.3 × 10−4 ± 1.0 × 10−4 |

| R13A | NDa |

| T36A | NDa |

| T37A | 2.9 × 10−4 ± 2 × 10−5 |

| T38A | 1.03 × 10−3 ± 1.0 × 10−4 |

a ND, not determined due to low cleavage activity. See “Experimental procedures”.

In addition to the canonical 8-nt product produced by all MazF-mt6 variants, RNA products of 9–11 nt were also seen but at varying extents depending on the variant (Fig. 4A). For example, MazF-mt6 variants D10A, R13A, and T36A that had large impacts on RNA degradation produced additional RNA products in similar amounts as compared with the canonical 8-nt product. In contrast, MazF-mt6 variants T37A and T38A that had a modest impact on overall activity produced products at the canonical position to the largest extent (40 and 60%, respectively, of overall product production), and 9–11-nt RNAs were only seen at low levels (2–13%). The MazF-mt6 K11A variant impacts cleavage to a minimal extent (Table 2; 3-fold); however, the major RNA product was 11 nt, corresponding to cleavage between U1943 and U1944. Thus, in addition to these MazF variants altering activity at the major cleavage site, they also seem to impact specificity. Another possibility is that in the absence of the 50S subunit the MazF-mt6 dimer may be more flexible in how it engages the bulged loop containing the consensus sequence, thus resulting in nucleotide promiscuity.

Discussion

Bacterial toxins regulate growth in response to environmental stress including antibiotic treatment (32). In E. coli, there is a single MazF toxin family member that cleaves free mRNA to inhibit translation (31). The MazF family is expanded to nine members in M. tuberculosis concurrent with the expansion of different target RNAs including tRNAs and rRNAs (12–14). This expansion suggests that M. tuberculosis MazFs may contain different structural elements to recognize diverse RNA substrates. In support of this, M. tuberculosis MazF sequence alignments reveal truncations in specific loop regions known to interact with RNA (11). The structure of MazF-mt6 reveals this MazF family member adopts a nearly identical tertiary fold as BsMazF and EcMazF (19, 29) (r.m.s.d. = 1.4 and 1.9 Å, respectively). Despite this similarity, MazF-mt6 contains a significantly shorter β1-β2 linker, the region known to contact its RNA substrate (19). MazF β1-β2 linkers typically contain 13 residues that surround the single-stranded mRNA substrate. The MazF-mt6 β1-β2 linker is truncated to five residues, which we predict would alter how it interacts with H70. H70 adopts a stem-loop structure with an internal bulged loop region where the MazF-mt6 cleavage site is located. Therefore, the length of the β1-β2 linker may be a consequence of the rigidity of the RNA it encounters. For example, MazFs that recognize flexible RNAs such as single-stranded mRNAs may require the loop to confine and orient the substrate. The H70 RNA likely requires less remodeling by the β1-β2 linker, and therefore alteration of this MazF-mt6 region may allow for different MazF homologues to distinguish among diverse RNAs.

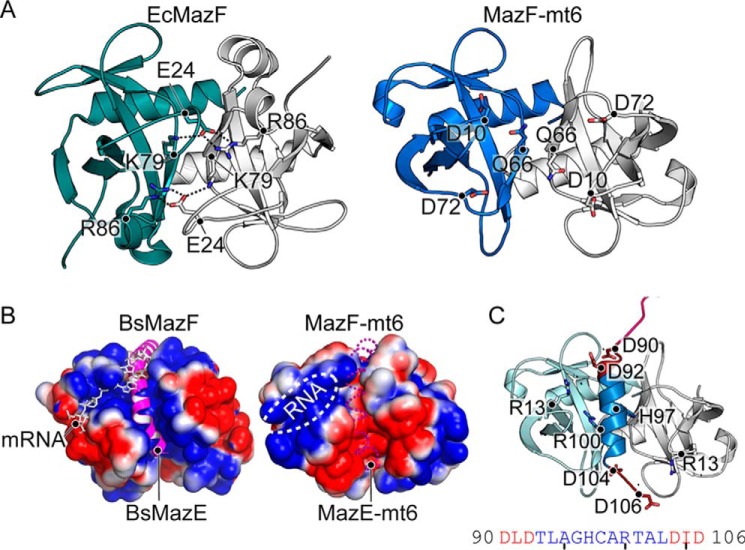

In addition to the β1-β2 linker interacting directly with RNA substrates, this region also modulates an open to a closed MazF state, effectively functioning as a gate to allow either RNA or its cognate antitoxin MazE to bind (29). In the context of a MazF dimer, which forms the closed state, the β1-β2 linker extends across the face of the monomer to interact with the adjacent MazF monomer (19). These interactions are mediated by symmetry-related electrostatic contacts between the distal end of the β1-β2 linker (Glu-24) and β6/α3 of the other monomer (Lys-79 and Arg-86) (Fig. 5A). This β1-β2 linker extension additionally establishes a positively charged RNA-binding pocket and obscures an adjacent and slightly overlapping positively charged region where the antitoxin MazE binds (29). Therefore, this closed state appears to direct mRNA binding while preventing MazE binding. Antitoxin MazE binding induces an open state by displacing the β1-β2 linker and thus disrupting interactions between the MazF monomers, causing a reorganization of MazF active-site residues (29). β1-β2 linker residue Glu-24 is critical for MazF activity (29), suggesting that maintenance of interactions between the monomers is important for MazF homologues that recognize mRNA.

Figure 5.

Comparison of MazFs. A, comparison of electrostatic interactions between the EcMazF β1-β2 and β5-β6 linkers with an adjacent EcMazF dimer (PDB code 5CR2) (left) with the absence of electrostatic interactions between MazF-mt6 dimers (right). Residues responsible for stabilizing the β1-β2 linker in EcMazF are shown as sticks with dotted lines highlighting ionic bonds. The equivalent residues to EcMazF are shown for MazF-mt6, but there are no interactions between these residues. B, electrostatic surface potential of BsMazF with both the MazE C-terminal α-helix (magenta) and the mRNA (white) shown to emphasize regions where their binding overlaps (PDB code 4ME7) (left). The electrostatic surface potential of MazF-mt6 with both the putative antitoxin-binding path (dashed magenta α-helix) and the RNA-binding pocket (white circle) is shown. The putative antitoxin-binding path is negatively charged in contrast to BsMazF. C, homology model of MazE-mt6 C-terminal α-helix (blue) superimposed onto MazF-mt6. MazF-mt6 catalytic residue Arg-13 is predicted to be close to MazE-mt6 residues Asp-90, Asp-92, Asp-104, and Asp-106, which could potentially disorder the MazF-mt6 active site. The MazE-mt6 peptide sequence is shown below.

The structure of MazF-mt6 reveals a truncated β1-β2 linker, suggesting that it likely does not undergo conformational changes to convert from a closed to an open state as seen in other MazF homologues. The shortening of β1-β2 allows for a permanently accessible, positively charged channel where RNA binds, whereas at the dimer interface, a negatively charged rather than a positively charged surface forms (Fig. 5B). A C-terminal MazE α-helix typically binds at the positively charged MazF dimer interface (19). However, MazF-mt6 lacks this positively charged surface (Fig. 5B). This suggests that MazE-mt6 antitoxin binding required to neutralize MazF-mt6 may be distinct from other MazEs solved to date. Homology modeling of MazE-mt6 predicts a C-terminal α-helix similar to other structures of MazE and ParD (19, 29, 33, 34). Two positively charged residues align on one side of the α-helix, which could bind the negatively charged dimer interface (Fig. 5C). As mentioned, MazE binding disrupts the MazF active site and in particular the catalytic arginine (29). Modeling of the MazE-mt6 C-terminal α-helix bound to MazF-mt6 indicates that MazE-mt6 may be able to interact with catalytic Arg-13, suggesting that active-site disruption could occur.

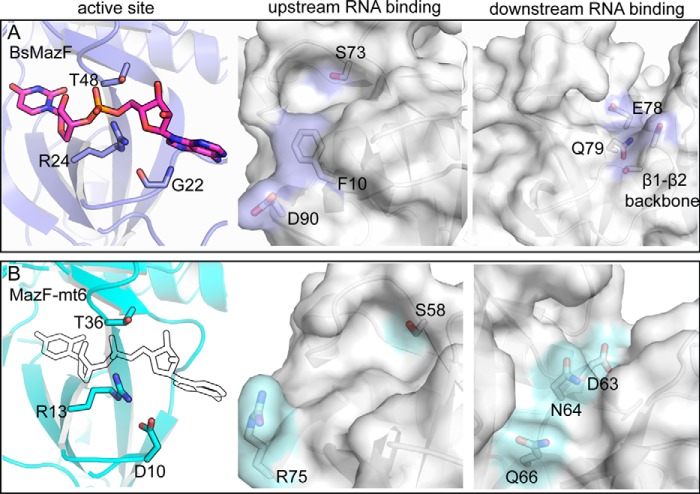

MazF endoribonucleases cleave RNA substrates via a proton-charge relay mechanism whereby an arginine functions as both a general acid and base and a threonine or serine stabilizes the transition state (29, 35) (Fig. 6A). In the absence of MazE and therefore containing a longer β1-β2 linker in a closed state, the catalytic arginine of MazF forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone (Gly-22), which is located at the distal end of the β1-β2 linker (Fig. 6A), a region missing in MazF-mt6. Instead, the shorter MazF-mt6 β1-β2 linker forms an electrostatic interaction with Arg-13 using the negatively charged carboxyl group of Asp-10 (Fig. 6A). In MazF, a threonine is located adjacent to the scissile phosphate and is predicted to stabilize the transition state, and in MazF-mt6, Thr-36 is in an equivalent location. We show that both Asp-10 and Thr-36 are critical for MazF-mt6 activity by either stabilizing the catalytic Arg-13 or the RNA, respectively. Other nearby MazF-mt6 residues including Lys-11, Thr-37, and to a lesser extent Thr-38 potentially contribute to RNA substrate stabilization by the formation of electrostatic interactions with the phosphate backbone or ribose as these residues are close to Arg-13 and Thr-36 (Fig. 2B). Although Thr-38 is adjacent to the active site, our data suggest that this residue has no significant role in RNA catalysis. Therefore, despite the significantly shorter β1-β2 linker, MazF-mt6 active-site residues form functionally equivalent interactions seen in other MazF orthologues.

Figure 6.

Comparison of MazF nucleotide specificities. A, BsMazF active-site residues Gly-22, Arg-24, and Thr-48 interact with its mRNA substrate (PDB code 4MDX) (left panel). The BsMazF upstream and downstream RNA-binding regions with proposed key residues are indicated. B, the MazF-mt6 active-site residues Asp-10, Arg-13, and Thr-36 with a modeled RNA bound (outline). The equivalent MazF-mt6 upstream and downstream RNA-binding regions with potentially key residues are highlighted.

MazFs cleave single-stranded mRNA at a consensus sequence of 5′-ACA-3′ with BsMazF requiring at least one uridine flanking the 5′- and 3′-ends of the consensus (27, 31). MazF-mt6 differs by requiring an additional uridine upstream of the consensus 5′-UU↓CCU-3′ sequence of the cleavage site (13). Structurally aligning the MazF-RNA complex to MazF-mt6 suggests several potential residues that could contribute to H70 RNA specificity. For upstream specificity, MazF-mt6 Arg-75 (located on β7) is located in a similar position as BsMazF Phe-10 and Asp-91, which recognize the −2 uridine position (Fig. 6B). A conserved BsMazF serine (Ser-73) is located in a pocket formed by the β4-β5 linker and interacts with the Watson-Crick face of the −1 uridine. MazF-mt6 Ser-58 likely fulfils an analogous role (Fig. 6B). In previously solved structures of MazF, the β1-β2, β3-β4, and β5-β6 linker residues recognize the downstream nucleotides ACAU (19). Because MazF-mt6 has a significantly shorter β1-β2 linker, the β5-β6 and β3-β4 regions are likely the only linkers responsible for base-specific recognition. The +1 position is recognized by the elongated β1-β2 linker, but in the case of MazF-mt6, the +1 cytidine may be recognized by β5-β6 linker residue Gln-66 because it is located in an equivalent position (Fig. 6B). MazF-mt6 residues Asp-63 and Asn-64 align with the MazF residues Glu-78 and Gln-79, suggesting that these residues play similar roles in base-specific nucleotide interactions of the +2 and +3 regions. Lastly, by containing a truncated β1-β2 linker, the RNA-binding path is deeper, potentially allowing a structured RNA like the bulged loop region containing the H70 consensus sequence to better fit on the surface of MazF-mt6.

MazF homologues are part of the PemK-like endonuclease family that cleave single-stranded mRNA transcripts (27). The one exception is the E. coli F-plasmid CcdB toxin that inhibits bacterial growth by binding to DNA gyrase to prevent replication (36). Despite having different functions and targeting different types of molecules, CcdB toxins are almost identical to MazFs (37) (Fig. 7). However, one key difference is the surface each uses to engage their different substrates. For example, β1-β2, β3-β4, and β5-β6 linkers of MazF interact with RNA, whereas the α4 dimer interface of CcdB binds GyrA, a region on the opposite side of MazF (Fig. 7) (38). Additionally, to bind GyrA, CcdB toxin bends 12° at the α4-α4 dimer interface, a movement that disorders the β1-β2 linker (Fig. 7C) (37). CcdA antitoxin binding orders the CcdB β1-β2 linker but prevents the α4-α4 conformational rearrangement required to bind GyrA. Therefore, the ordering/disordering transition is opposite between MazFs and CcdB (19, 29, 38) as has been suggested previously (37). The lack of apparent β1-β2 linker regulation in MazF-mt6 indicates that how it is regulated has diverged from other MazFs.

Figure 7.

Structural comparison of MazF-mt6 and CcdB toxin. A, E. coli CcdB toxin similarly forms a homodimer toxin (one monomer shown in green with the other shown in gray) with important secondary structural regions labeled (PDB code 1X75). B, two homodimers of MazF-mt6 are shown (one monomer shown in light gray with the other shown in dark gray) with the putative RNA-binding regions colored in red. C, a 90° rotated view of A of CcdB bound to GyrA (cyan) illustrating how CcdB α4 from both monomers engages its substrate, which is located on the opposite side of the RNA-binding domain of MazF-mt6. To bind GyrA, CcdB bends 12° (shown in dark gray). CcdB toxin in the absence of GyrA is shown for comparison (white).

Experimental procedures

M. tuberculosis MazF-mt6 and MazF-mt6 variant purifications

Overnight cultures of E. coli C41(DE3) cells (Lucigen) transformed with pCold-His6-TF-MazF-mt6 (a kind gift from the Woychik laboratory) (13) were diluted 1:100 in lysogeny broth medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. Cultures were grown to an A600 of 1.0 at 37 °C and transferred to 15 °C for 30 min, and protein expression was induced with 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and grown for 24 h at 15 °C. Cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer (40 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 500 mm NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol, 0.1% (w/w) Triton X-100, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 20 mm imidazole, 0.1 mm benzamidine, and 0.1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride) and lysed using an Emulsiflex C5 (Avastin). Cell debris was clarified by centrifugation at 35,000 × g for 50 min, and the cell lysate was applied to a 5-ml Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column (GE Healthcare) at 10 °C. The His6-TF-MazF-mt6 fusion protein was eluted with a linear gradient of lysis buffer without Triton X-100 or protease inhibitors but containing 500 mm imidazole. The sample was dialyzed overnight into thrombin cleavage buffer (20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 2.5 mm CaCl2), 1 unit of thrombin/200 μg of protein was added at room temperature for 3 h, and the sample was further incubated overnight at 10 °C. The cleaved His6-TF-MazF was reapplied to the Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column, and MazF-mt6 was collected from the flow-through fraction. MazF-mt6 was further purified and buffer-exchanged on a size-exclusion Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) into 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 250 mm KCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol, and 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol. MazF-mt6 was determined to be 95% pure by 15% SDS-PAGE, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

MazF-mt6 variants were constructed using site-directed mutagenesis, and sequences were verified by DNA sequencing (oligos listed in supplemental Table S1). MazF-mt6 variant purifications were performed similarly to wild type. Each variant eluted as a single, symmetrical peak at the expected volume during the gel-filtration step as wild type, suggesting that the variants are properly folded.

MazF-mt6 crystallization, data collection, and structure determination

MazF-mt6 (10 mg/ml) crystallized by hanging-drop vapor diffusion in 50 mm sodium cacodylate, pH 6.0, 10 mm MgCl2, and 1.05 m LiSO4 at 20 °C in 3 weeks to dimensions of ∼100 μm3. The crystals were cryoprotected in 50% (w/v) lithium sulfate, 30% glycerol, and 150 mm ammonium tartrate for ∼60 s and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Native X-ray diffraction data sets were collected at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team 24-IDC beamline at the Advanced Photon Source. The data sets were collected under cryogenic conditions (100 K) using 0.979-Å radiation. The data were integrated and scaled to 2.9 Å using the X-ray Detector Software (XDS) package (39). The BsMazF-mRNA complex (PDB code 4MDX) was used as a search model (with the mRNA removed), and all MazF residues were changed to alanine during molecular replacement using AutoMR from the PHENIX software suite (20). Multiple rounds of positional, B-factor, and energy minimization refinement in PHENIX were followed by manual model rebuilding in Coot performed with Rwork and Rfree converging to 23.9/27.1% (21). The final MazF-mt6 model consisted of residues 1–99 of 103 total. The model quality was determined using MolProbity of the PHENIX validation suite, and figures were generated using PyMOL (40).

23S rRNA cleavage and reverse transcription

E. coli MRE600 70S was purified as described previously (41). The 50S subunit was purified by dialyzing the 70S ribosome in low magnesium (2.5 mm) and separated by sucrose gradient. The 23S rRNA H70 residues 1933–1967 were chemically synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies; 5′-1933GCGAAAUUCCUUGUCGGGUAAGUUCCGACCUGC1967-3′). E. coli 50S or H70 RNA was incubated at 37 °C for 45 min with a 10-fold molar excess of wild-type MazF-mt6 in 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm KCl, and 10 mm NH4Cl. Reactions were halted by the addition of either phenol:chloroform (5:1) or phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) for H70 RNA or 50S, respectively. Both RNAs were next chloroform-extracted once, precipitated overnight at −20 °C by the addition of 0.3 m sodium acetate, pH 5.2, and 3 volumes of ice-cold 100% ethanol, and resuspended in Milli-Q water.

The reverse transcription primer (Integrated DNA Technologies; 5′-GTCGGAACTTACCCGAC-3′) was 5′-32P-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), and 4 pmol of the primer was annealed to 4 (50S) or 7 (H70) pmols of RNA in 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and 50 mm NaCl to 90 °C or 65 °C, respectively. These reactions were slowly cooled to 42 °C by removing the heat block and placing on the benchtop at room temperature. The reverse transcription reactions were initiated with the addition of 1 μm dATP, 1 μm dGTP, and 1 μm dTTP, limiting amounts of 0.1 μm ddCTP and Protoscript II reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs) as described previously (18). Reactions were incubated at 42 °C for 1 h, then halted with the addition of 1 volume of formamide dye (100% (v/v) deionized formamide, 0.01% (w/v) bromphenol blue, and 0.01% (w/v) xylene cyanol), and heated to 90 °C for 2 min. Dideoxy sequencing reactions were performed as described previously (18). Samples were run on a preheated 50% urea and 20% polyacrylamide gel at 37 mA (limiting) for 90 min. The gel was fixed in 20% (v/v) methanol, 20% (v/v) acetic acid, and 3% glycerol (v/v) for 60 min; dried for 1 h, and exposed to a phosphor screen for 1 hr. Exposure was visualized using a Typhoon FLA 7000 gel imager (GE Healthcare), with the band density determined by ImageQuant (GE Healthcare).

RNA cleavage assays

H70 was 5′-32P-labeled as described above and incubated (0.2 μm RNA) with 2 μm wild-type MazF-mt6 or MazF-mt6 variants for 45 min at 37 °C. Aliquots of the reactions were halted at 1-, 3-, 5-, 10-, 25-, and 45-min time points with the addition of 1 volume of formamide gel loading buffer and heated to 70 °C for 2 min. Samples were run on a 50% urea and 20% polyacrylamide gel at 37 mA (limiting) for 2 h. The gel was fixed in 40% ethanol, 20% acetic acid, and 3% glycerol for 1 h; dried for 90 min; then exposed to a GE Healthcare phosphor screen for 30 min. Exposure was visualized using a Typhoon FLA 7000 gel imager (GE Healthcare), with the band density determined by ImageQuant (GE Healthcare). Background density was subtracted using default settings. The amount of cleavage product was determined by determining the amount of full-length RNA in each lane. The amount of full-length RNA was divided by the total lane density for each sample, and the reciprocal of the resulting reaction was recorded as the amount of RNA cleaved. The amount of cleaved product against time were fit by GraphPad Prism 5 using the following single-exponential equation.

| (Eq. 1) |

where Pmax is the RNA cleavage product plateau (pmol of mRNA cleaved), k is the observed rate constant (min−1), and t is the time the reaction progressed (min). The rates of both MazF-mt6 R13A and T36A were too low to fit the data points to the single-turnover equation with an R2 >80%.

Homology modeling of MazE-mt6

The homology model of MazE-mt6 was generated by the HHpred homology model workflow and MODELLER using the optimal multiple template function (42, 43). The structural templates used in MODELLER to generate the MazE-mt6 homology model were E. coli ParD (from the ParD-ParE complex; PDB code 3KXE, chain C (33); 20% sequence identity to MazE-mt6), Mesorhizobium opportunistum ParD3 (from the ParD3-ParE3 complex; PDB code 5CEG, chain A (34); 12% sequence identity), Homo sapiens calmodulin (PDB code 2K61, chain A (44); 7.8% sequence identity), E. coli NikR (from NikR-DNA operator complex; PDB code 2HZA, chain A (45); 9.3% sequence identity), and Streptococcus agalactiae CopG (PDB code 2CPG, chain A (46); 16.3% sequence identity).

Author contributions

E. D. H. and C. M. D. designed research. E. D. H. and S. J. M. performed research. E. D. H. and C. M. D. analyzed data. E. D. H. and C. M. D. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dunham laboratory members Drs. T. Maehigashi, J. Meisner, and M. A. Schureck for helpful discussions throughout the project; Dr. M. Witek for providing purified E. coli 50S; and Dr. G. L. Conn for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Woychik for reagents and Woychik laboratory member Dr. J. M. Schifano for technical guidance. This work is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamline, which is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health Grant P41 GM103403, and at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team beamline. The Pilatus 6M detector on the 24-ID-C beamline is funded by a National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs High End Instrumentation Grant S10 RR029205. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the United States Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the United States DOE under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Award MCB 0953714 (to C. M. D.) and Emory School of Medicine bridge funds. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5 and Table S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 5UCT) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- H70

- Helix 70

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- TF

- trigger factor

- BsMazF

- B. subtilis MazF

- SH3

- Src homology 3

- PemK

- plasmid emergency maintenance K

- EcMazF

- E. coli MazF toxin.

References

- 1. Maisonneuve E., Castro-Camargo M., and Gerdes K. (2013) (p)ppGpp controls bacterial persistence by stochastic induction of toxin-antitoxin activity. Cell 154, 1140–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yamaguchi Y., Park J. H., and Inouye M. (2011) Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 61–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lobato-Márquez D., Díaz-Orejas R., and García-Del Portillo F. (2016) Toxin-antitoxins and bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 592–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gerdes K., and Maisonneuve E. (2012) Bacterial persistence and toxin-antitoxin loci. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66, 103–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pandey D. P., and Gerdes K. (2005) Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 966–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pedersen K., Zavialov A. V., Pavlov M. Y., Elf J., Gerdes K., and Ehrenberg M. (2003) The bacterial toxin RelE displays codon-specific cleavage of mRNAs in the ribosomal A site. Cell 112, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hurley J. M., and Woychik N. A. (2009) Bacterial toxin HigB associates with ribosomes and mediates translation-dependent mRNA cleavage at A-rich sites. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18605–18613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prysak M. H., Mozdzierz C. J., Cook A. M., Zhu L., Zhang Y., Inouye M., and Woychik N. A. (2009) Bacterial toxin YafQ is an endoribonuclease that associates with the ribosome and blocks translation elongation through sequence-specific and frame-dependent mRNA cleavage. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 1071–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aizenman E., Engelberg-Kulka H., and Glaser G. (1996) An Escherichia coli chromosomal “addiction module” regulated by guanosine [corrected] 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate: a model for programmed bacterial cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 6059–6063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hazan R., Sat B., and Engelberg-Kulka H. (2004) Escherichia coli mazEF-mediated cell death is triggered by various stressful conditions. J. Bacteriol. 186, 3663–3669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhu L., Zhang Y., Teh J. S., Zhang J., Connell N., Rubin H., and Inouye M. (2006) Characterization of mRNA interferases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18638–18643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schifano J. M., Vvedenskaya I. O., Knoblauch J. G., Ouyang M., Nickels B. E., and Woychik N. A. (2014) An RNA-seq method for defining endoribonuclease cleavage specificity identifies dual rRNA substrates for toxin MazF-mt3. Nat. Commun. 5, 3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schifano J. M., Edifor R., Sharp J. D., Ouyang M., Konkimalla A., Husson R. N., and Woychik N. A. (2013) Mycobacterial toxin MazF-mt6 inhibits translation through cleavage of 23S rRNA at the ribosomal A site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8501–8506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schifano J. M., Cruz J. W., Vvedenskaya I. O., Edifor R., Ouyang M., Husson R. N., Nickels B. E., and Woychik N. A. (2016) tRNA is a new target for cleavage by a MazF toxin. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 1256–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., and Koonin E. V. (2009) Comprehensive comparative-genomic analysis of type 2 toxin-antitoxin systems and related mobile stress response systems in prokaryotes. Biol. Direct. 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yusupov M. M., Yusupova G. Z., Baucom A., Lieberman K., Earnest T. N., Cate J. H., and Noller H. F. (2001) Crystal structure of the ribosome at 5.5 Å resolution. Science 292, 883–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weixlbaumer A., Petry S., Dunham C. M., Selmer M., Kelley A. C., and Ramakrishnan V. (2007) Crystal structure of the ribosome recycling factor bound to the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 733–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jackman J. E., and Phizicky E. M. (2006) tRNAHis guanylyltransferase catalyzes a 3′-5′ polymerization reaction that is distinct from G-1 addition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8640–8645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simanshu D. K., Yamaguchi Y., Park J. H., Inouye M., and Patel D. J. (2013) Structural basis of mRNA recognition and cleavage by toxin MazF and its regulation by antitoxin MazE in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Cell 52, 447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L. W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., and Zwart P. H. (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., and Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cook G. M., Robson J. R., Frampton R. A., McKenzie J., Przybilski R., Fineran P. C., and Arcus V. L. (2013) Ribonucleases in bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 523–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loris R., Dao-Thi M. H., Bahassi E. M., Van Melderen L., Poortmans F., Liddington R., Couturier M., and Wyns L. (1999) Crystal structure of CcdB, a topoisomerase poison from E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 285, 1667–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hargreaves D., Santos-Sierra S., Giraldo R., Sabariegos-Jareño R., de la Cueva-Méndez G., Boelens R., Díaz-Orejas R., and Rafferty J. B. (2002) Structural and functional analysis of the kid toxin protein from E. coli plasmid R1. Structure 10, 1425–1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang J., Zhang Y., Zhu L., Suzuki M., and Inouye M. (2004) Interference of mRNA function by sequence-specific endoribonuclease PemK. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20678–20684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kamada K., Hanaoka F., and Burley S. K. (2003) Crystal structure of the MazE/MazF complex: molecular bases of antidote-toxin recognition. Mol. Cell 11, 875–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park J. H., Yamaguchi Y., and Inouye M. (2011) Bacillus subtilis MazF-bs (EndoA) is a UACAU-specific mRNA interferase. FEBS Lett. 585, 2526–2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holm L., and Rosenström P. (2010) Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–W549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zorzini V., Mernik A., Lah J., Sterckx Y. G., De Jonge N., Garcia-Pino A., De Greve H., Versées W., and Loris R. (2016) Substrate recognition and activity regulation of the Escherichia coli mRNA endonuclease MazF. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 10950–10960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han J. S., Lee J. J., Anandan T., Zeng M., Sripathi S., Jahng W. J., Lee S. H., Suh J. W., and Kang C. M. (2010) Characterization of a chromosomal toxin-antitoxin, Rv1102c-Rv1103c system in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 400, 293–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y., Zhang J., Hoeflich K. P., Ikura M., Qing G., and Inouye M. (2003) MazF cleaves cellular mRNAs specifically at ACA to block protein synthesis in Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell 12, 913–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hauryliuk V., Atkinson G. C., Murakami K. S., Tenson T., and Gerdes K. (2015) Recent functional insights into the role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 298–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dalton K. M., and Crosson S. (2010) A conserved mode of protein recognition and binding in a ParD-ParE toxin-antitoxin complex. Biochemistry 49, 2205–2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aakre C. D., Herrou J., Phung T. N., Perchuk B. S., Crosson S., and Laub M. T. (2015) Evolving new protein-protein interaction specificity through promiscuous intermediates. Cell 163, 594–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guillén Schlippe Y. V., and Hedstrom L. (2005) A twisted base? The role of arginine in enzyme-catalyzed proton abstractions. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 433, 266–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dao-Thi M. H., Van Melderen L., De Genst E., Afif H., Buts L., Wyns L., and Loris R. (2005) Molecular basis of gyrase poisoning by the addiction toxin CcdB. J. Mol. Biol. 348, 1091–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zorzini V., Buts L., Sleutel M., Garcia-Pino A., Talavera A., Haesaerts S., De Greve H., Cheung A., van Nuland N. A., and Loris R. (2014) Structural and biophysical characterization of Staphylococcus aureus SaMazF shows conservation of functional dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 6709–6725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dao-Thi M. H., Van Melderen L., De Genst E., Buts L., Ranquin A., Wyns L., and Loris R. (2004) Crystallization of CcdB in complex with a GyrA fragment. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 1132–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kabsch W. (2010) XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DeLano W. L. (2010) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3r1, Schrödinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 41. Witek M. A., and Conn G. L. (2016) Functional dichotomy in the 16S rRNA (m1A1408) methyltransferase family and control of catalytic activity via a novel tryptophan mediated loop reorganization. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 342–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sali A., Potterton L., Yuan F., van Vlijmen H., and Karplus M. (1995) Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins 23, 318–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Söding J., Biegert A., and Lupas A. N. (2005) The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W244–W248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bertini I., Kursula P., Luchinat C., Parigi G., Vahokoski J., Wilmanns M., and Yuan J. (2009) Accurate solution structures of proteins from X-ray data and a minimal set of NMR data: calmodulin-peptide complexes as examples. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 5134–5144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schreiter E. R., Wang S. C., Zamble D. B., and Drennan C. L. (2006) NikR-operator complex structure and the mechanism of repressor activation by metal ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13676–13681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gomis-Rüth F. X., Solá M., Acebo P., Párraga A., Guasch A., Eritja R., González A., Espinosa M., del Solar G., and Coll M. (1998) The structure of plasmid-encoded transcriptional repressor CopG unliganded and bound to its operator. EMBO J. 17, 7404–7415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.