Abstract

Introduction

Endovascular repair (TEVAR) has become an alternative to open repair for the treatment of ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysms (rTAA). The aim of this study was to assess national trends in the utilization of TEVAR for the treatment of rTAA and determine its impact on perioperative outcomes.

Methods

Patients admitted with a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm between 1993 and 2012 were identified from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Patients were grouped in accordance with their treatment: TEVAR, open repair, or nonoperative treatment. The primary outcomes were treatment trends over time and in-hospital death. Secondary outcomes included perioperative complications and length of stay. Trend analyses were performed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend, and adjusted mortality risks were established using multivariable logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 12,399 patients were included, with 1622 (13%) undergoing TEVAR, 2808 (23%) undergoing open repair, and 7969 (64%) not undergoing surgical treatment. TEVAR has been increasingly utilized from 2% of total admissions in 2003–2004 to 43% in 2011–2012 (P<.001). Concurrently, there was a decline in the proportion of patients undergoing open repair (29% to 12%, P<.001) and nonoperative treatment (69% to 45%, P<.001). The proportion of patients undergoing surgical repair has increased for all age groups since 1993–1994 (P<.001 for all), but was most pronounced among those aged 80 years with a 7.5 fold increase. After TEVAR was introduced, procedural mortality decreased from 36% in 2003–2004 to 27% in 2011–2012 (P<.001), while mortality among those undergoing nonoperative remained stable between 63% and 60% (P=.167). Overall mortality following rTAA admission decreased from 55% to 42% (P<.001). Since 2005, mortality for open repair was 33% and 22% for TEVAR (P<.001). In adjusted analysis, open repair was associated with a two-fold higher mortality than TEVAR (OR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.7 – 2.5).

Conclusion

TEVAR has replaced open repair as primary surgical treatment for rTAA. The introduction of endovascular treatment appears to have broadened patient eligibility for surgical treatment, particularly among the elderly. Mortality following rTAA admission has declined since the introduction of TEVAR, which is the result of improved operative mortality, as well as the increased proportion of patients undergoing surgical repair.

Introduction

A ruptured descending thoracic aortic aneurysm (rTAA) is a life-threatening diagnosis, with an estimated mortality exceeding 90%.1 The majority of patients die before making it to the emergency department. For those hemodynamically stable enough to reach the hospital and undergo surgery,1 traditional open repair requires an emergency thoracotomy to replace the diseased aorta with an interposition graft. Despite the fact that hospitalized patients are presumed to have a better prognosis, mortality following surgery is as high as 45%,2, 3 with surviving patients often suffering disabling complications such as paraplegia and stroke.2, 4–6

As a minimally invasive alternative, endovascular repair (TEVAR) for rTAA was first introduced and described by Semba et al in 1997.7, 8 In subsequent years, single institution studies were performed to evaluate its feasibility, and performance compared to conventional open repair.4, 9–14 Although some of these studies showed encouraging perioperative results favoring TEVAR, they were often limited by small numbers, and the inclusion of other acute aortic pathologies. Moreover, an absolute perioperative survival benefit of TEVAR over open repair could not be confirmed. 4, 14 Reports on outcome of rTAA using early national data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) yielded conflicting results, despite using the same cohort of TEVAR patients.

Previous studies have demonstrated that for patients presenting with a traumatic thoracic aortic injury, the introduction of TEVAR has reduced the proportion of patients managed nonoperatively.17, 18 For rTAA patients, however, it is unknown whether the introduction TEVAR has broadened their treatment eligibility.17 The purpose of this study was to assess national trends in the treatment of rTAA, focusing on the relative utilization and outcome of TEVAR, open repair, and nonoperative treatment.

Methods

For this study, we used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). The NIS is the largest US all-payer inpatient database, and is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). From the U.S. States participating in the HCUP, which comprise of 96% of the U.S. population in more recent years, a 20% stratified sample of hospitals is selected to accurately represent hospital admissions nationally.19 Actual annual U.S. hospitalization volumes are approximated using hospital sampling weights. The weighted estimates are utilized for all analyses in this study, as recommended by the AHRQ. The Institutional Review Board of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center approved this study and patient consent was waived, due to the de-identified nature of the data.

Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9). All patients admitted with a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm (411.1) were identified. Patients were subsequently divided in the open repair group (38.35) and the TEVAR group (39.73). Those with a primary diagnosis of a ruptured aneurysm without mention of any procedure were considered nonoperatively treated. In an effort to capture TEVAR cases before TEVAR procedure coding was introduced in 2005, patients with a primary diagnosis of a ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm in combination with mentioning of EVAR (39.71) or insertion of non-drug eluting peripheral (non-coronary) vessel stent (39.90) were also considered to have undergone endovascular repair. Patients with both a procedure code for open repair and TEVAR were excluded. In addition, those with a concomitant diagnosis for thoracoabdominal aneurysm (diagnosis codes: 441.3–441.9 or procedure codes: 38.44, 39.71), aortic dissection (diagnosis codes: 441.00–441.03), or connective tissue disorder (diagnosis codes: 446.0–446.7, 758.6, 759.82) were excluded from this study. To separate ascending from descending aneurysms, patients with procedure codes for cardioplegia (39.63), valve surgery (35.00–35.99), and procedures on the vessels of the heart (36.00–36.99, 37.0, 37.2, 37.31–37.90, 37.93, 37.99) were also excluded, as they are more likely to represent aneurysms of the ascending aorta. We compared patient demographics (age, gender, race), and comorbid conditions (coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic kidney disease, and cerebrovascular disease). We additionally assessed differences in hospital characteristics, including hospital bedsize (small, medium, large), setting and teaching status (rural, urban non-teaching, urban teaching). Hospital bedsize category varies according to location and teaching status. Small hospital bedsize is defined as 1–49, 50–99 and 1–299 beds, respectively for rural, urban non-teaching and urban teaching hospitals, medium bedsize as 50–99, 100–199, 300–499, respectively, and 100+, 200+, and 500+ beds is considered a large bedsize hospital, respectively. Adverse in-hospital outcomes included death, cardiac or respiratory complications, paraplegia, stroke, acute renal failure, wound dehiscence, infection. Cardiac complications include postoperative myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, and ventricular fibrillation (Supplemental Table I). A respiratory complication was defined as a postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary insufficiency after trauma or surgery, transfusion-related acute lung injury, or acute respiratory failure. Discharge to home and length of stay were additionally documented. Comparative analysis of the different treatment approaches is limited to the years 2005–2012, since this was the period both treatment approaches were available.

For this study we also utilized the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER), an epidemiological internet based database maintained by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),20 to assess national cause-specific age-adjusted death rates due to thoracic aortic aneurysms (ICD-10 code: S25.0). More information on WONDER can be found on http://wonder.cdc.gov/.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics were described as counts and percentages (dichotomous variables), or means and standard deviations (continuous variables). Differences at baseline were assessed using Pearson’s chi-Square or Fisher’s exact testing, and Student’s t-test, where appropriate. Trend analyses were performed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. In order to assess the independent risk associated with treatment option for rTAA, we subsequently performed multivariable logistic regression analysis. Predictors with a P <.1 were entered into the multivariable model. Due to the limited number of diagnoses that can be provided per patient in this dataset, less life-threatening comorbid conditions are underreported in more complex cases. Since these conditions act as confounders for less severe cases, we chose not to include comorbidities with protective risk estimates on the univariate screening in the multivariable model. Comorbidities excluded as a result were diabetes, hypertension, and cerebrovascular disease. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit testing was used to evaluate the multivariable model. All tests were two-sided and significance was considered when P<.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

A total of 12,399 patients were included, with 1622 (13%) undergoing TEVAR, 2808 (23%) undergoing open repair, and 7969 (64%) not undergoing surgical treatment.

Epidemiological trends

TEVAR has been increasingly utilized from 2% of total admissions in 2003–2004, and 16% in 2005–2006, to 43% in 2012 (P<.001, Figure 1). Concurrently, the proportion of patients undergoing open repair declined from 29% to 12% (P<.001). Despite a decrease in open repair utilization, the overall proportion of patients undergoing surgical repair following rTAA admission dramatically increased once TEVAR received FDA approval in 2005 (31% to 55%, P<.001).

Figure I.

Annual proportions of the treatment strategies for the treatment of rTAA

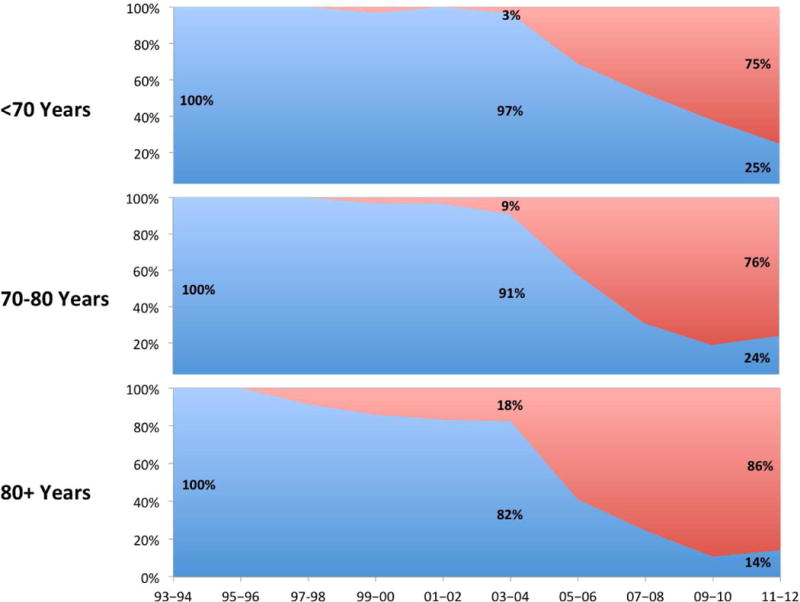

Although an increase in surgical repair was observed in all age groups, it was not uniform. The utilization of surgical treatment for patients under 70 increased 207% from 1993–1994 to 2011–2012 (P<.001, Figure 2A). For those aged 70–80 years, this was 177% (P<.001). With a 750% increase over the study period, the shift towards operative management was most pronounced among those aged 80 and above. Figure 2B illustrates that the adoption to TEVAR started relatively early among the eldest patients, as 18% of patients aged 80 and over were undergoing TEVAR prior to its FDA approval (<70 years: 3%; 70–80 years: 9%, P=.004). In 2011–2012, only 14% of patients aged 80+ underwent open repair, which was significantly lower compared to the <70 group (25%) and 70–80 group (24%, P=.008)).

Figure IIA.

Annual changes in rates of surgical repair by age (index volume: 1993–1994)

Figure IIB.

Annual proportions of TEVAR vs. open repair stratified by age group

When population-adjusted trends were evaluated, an overall decrease in rTAA admissions was observed from 1993 to 2004 (4.7 to 3.6 per million, Figure 3), a rate that stabilized thereafter. The number of patients surgically treated increased since 2003–2004 from 1.4 to 1.9 per million. This was observed among patients under 70 years (0.8 to 1.1 per million), but more strongly among patients aged 80 and above (3.5 to 9.9 per million).

Figure III.

Population-adjusted trends in rTAA admission rates, death rates, and surgical repair utilization (per million)

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table I. When comparing TEVAR patients to those undergoing open repair, we found that TEVAR patients were substantially older (72 years vs. 66 years, P<.001). In terms of comorbidities, TEVAR patients more often had diabetes (14% vs. 11%, P=.031), and hypertension (75% vs. 60%, P<.001). Additionally, coronary artery disease (27% vs. 18%, P<.001), and chronic kidney disease (21% vs. 11%, P<.001) were more common among those undergoing TEVAR compared to open repair. TEVAR was more often performed in academic centers (85% vs. 75%, P<.001), and larger bedsize hospitals (82% vs. 79%, P<.001) compared to open repair. In addition, TEVAR patients were significantly more often transferred from other hospitals than those undergoing open repair (32.6% vs. 25.9%, P<.001).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of patients admitted with rTAA between 2005–2012

| Procedure | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| TEVAR (N=1549) |

Open Repair (N=765) |

Nonoperative (N=2511) |

Overall | OR vs TEVAR | |

| Demographics | |||||

|

| |||||

| Age – years (SD) | 72.2 (13.2) | 66.0 (14.2) | 78.2 (12.7) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Age category – % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| < 70 years | 36.0% | 55.0% | 16.3% | ||

| 70–80 years | 30.0% | 27.6% | 26.3% | ||

| 80+ years | 34.1% | 17.4% | 57.5% | ||

| Female gender - % | 49.6% | 51.0% | 58.4% | <.001 | .526 |

| Non-white race - % | 27.3% | 27.1% | 23.3% | .016 | .922 |

|

| |||||

| Comorbidities | TEVAR | Open Repair | Nonoperative | Overall | OR vs TEVAR |

|

| |||||

| Coronary artery disease - % | 27.0% | 17.8% | 23.9% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Old myocardial infarction - % | 7.5% | 1.3% | 4.5% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Diabetes - % | 14.2% | 11.0% | 13.4% | .096 | .031 |

| Hypertension - % | 75.4% | 60.4% | 73.1% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Heart Failure - % | 14.5% | 13.3% | 14.0% | .762 | .462 |

| COPD - % | 18.7% | 17.0% | 18.0% | .619 | .328 |

| Chronic kidney disease - % | 20.8% | 11.0% | 15.2% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Cerebrovasc disease -% | 12.3% | 14.0% | 6.6% | <.001 | .263 |

|

| |||||

| Socioeconomic status | TEVAR | Open Repair | Nonoperative | Overall | OR vs TEVAR |

|

| |||||

| Income quartile | .538 | .207 | |||

| First | 27.1% | 25.9% | 27.1% | ||

| Second | 26.6% | 27.3% | 26.9% | ||

| Third | 25.6% | 22.8% | 23.9% | ||

| Fourth | 20.7% | 24.0% | 22.2% | ||

|

| |||||

| Hospital Characteristics | TEVAR | Open Repair | Nonoperative | Overall | OR vs TEVAR |

|

| |||||

| Hospital Setting - % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Rural | 1.5% | 0.7% | 11.9% | ||

| Urban non-teaching | 13.2% | 24.2% | 31.5% | ||

| Urban teaching | 85.3% | 75.2% | 56.5% | ||

| Hospital Bedsize - % | <.001 | <.001 | |||

| Small | 6.3% | 3.9% | 13.5% | ||

| Medium | 12.2% | 17.4% | 17.7% | ||

| Large | 81.5% | 78.7% | 68.8% | ||

| Transfer from other hospital | 36.2% | 25.9% | 12.5% | <.001 | <.0011 |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Perioperative mortality

In-hospital mortality was significantly lower for patients undergoing TEVAR compared to open repair (22% vs. 33%, P<.001, Table II). Following nonoperative treatment in-hospital mortality was 60%. In adjusted analysis, open repair was associated with a two-fold higher mortality compared to TEVAR (OR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.7 – 2.5, Table III), while nonoperative management was associated with a five-fold increase in mortality (OR: 5.0, 95% CI: 4.3 – 5.9). From 2005 onward, mortality after TEVAR increased non-significantly from 21% to 26% (P=.219, Figure 4), while mortality following open repair decreased significantly between 2003–2004 and 2011–2012 (36% to 29%, P=.005). Over that same time period, overall procedural mortality decreased from 36% to 27% (P<.001), while mortality among those undergoing nonoperative remained stable between 63% and 60% (P=0.167). As TEVAR became more widely adopted –and the proportion of patients undergoing nonoperative treatment decreased– overall mortality following rTAA admission decreased from 55% to 42% (P<.001).

Table II.

Perioperative outcomes of patients admitted with rTAA between 2005–2012

| Procedure | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| TEVAR (N=1549) |

Open Repair (N=765) |

Nonoperative (N=2511) |

Overall | OR vs TEVAR | |

| Death - % | 21.6% | 33.2% | 59.9% | <.001 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Cardiac complication – % | 16.6% | 31.2% | 17.0% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Paraplegia - % | 3.7% | 5.6% | 0.6% | <.001 | .031 |

| Stroke complication - % | 3.7% | 5.0% | 0.8% | <.001 | .165 |

| Acute renal failure - % | 21.8% | 25.1% | 9.6% | <.001 | .072 |

| Respiratory - % | 33.4% | 43.0% | 10.6% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Wound dehiscence - % | 0.9% | 3.7% | 0.2% | <.001 | <.001 |

| Postoperative infection - % | 0.6% | 3.8% | 0.2% | <.001 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Bleeding complication | 14.3% | 18.2% | 1.2% | <.001 | .015 |

|

| |||||

| Length of stay - days (IQR)α | 13.7 (12.7) | 17.2 (15.0) | 5.2 (7.3) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Discharge to home - % | 27.2% | 21.1% | 9.3% | <.001 | .002 |

Length of stay among those who did not die during hospitalization

Table III.

Multivariable analysis assessing risk factors for in-hospital mortality following admission for rTAA

| 30-day mortalityα | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEVAR | Reference | – | – |

| Open repair | 2.0 | 1.7 – 2.5 | <.001 |

| Nonoperative treatment | 5.0 | 4.3 – 5.9 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Age <70 years | Reference | – | – |

| 70 – 80 years | 1.1 | 0.96 – 1.4 | .134 |

| >80 years | 1.7 | 1.4 – 2.0 | <.001 |

| Male gender | 1.0 | 0.9 – 1.2 | .803 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.5 | 1.1 – 1.9 | .012 |

| Heart failure | 1.2 | 0.97 – 1.4 | .106 |

| COPD | 1.2 | 1.1 – 1.5 | .007 |

| ZIP household income | |||

| First quartile | 0.9 | 0.7 – 1.0 | .149 |

| Second quartile | 0.9 | 0.8 – 1.1 | .264 |

| Third quartile | .8 | 0.6 – 0.9 | .003 |

| Fourth quartile | Reference | – | – |

Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness of fit P=.180

Figure IV.

Trends in in-hospital mortality following rTAA admission

Despite an increase in rTAA admissions among those under age 70 after the introduction of TEVAR, in-hospital deaths declined after 2003–2004 (0.6 to 0.4 per million, Figure 3). Similarly, for those over 80, death following rTAA admission declined (16.7 to 13.3 per million), even though the rTAA admission incidence increased. The population-adjusted incidence of death following rTAA in patients 70–80 years of age also decreased considerably (7.1 to 3.0 per million), although this was concurrent with a strong decline in admission for rTAA. Similar declining trends were seen in the national WONDER data from the CDC, with rTAA mortality among patients less than 70 years declining from 1.0 to 0.8 per million between 2003–2004 and 2011–2012, and 42 to 22 per million among those aged 80 and above.

Perioperative complications

In addition to favorable mortality, TEVAR was associated with a lower incidence of cardiac complications (17% vs. 31%, P<.001), paraplegia (4% vs. 6%, P=.031), respiratory complications (33% vs. 43%, P<.001), wound dehiscence (0.9% vs. 4%, P<.001), postoperative infection (0.6% vs. 4%, P<.001), and bleeding complications (14% vs. 18%, P=.015) compared to open repair. Additionally, those undergoing TEVAR had a significantly shorter hospital stay (14 days vs. 17 days, P<.001), and were more likely to be discharged to home (27% vs. 21%, P=.002).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that since its introduction, the utilization of endovascular repair has rapidly increased for the treatment of rTAA, and is currently the primary mode of treatment. Aside from replacing open repair, the use of TEVAR has led to an increase in the proportion of rTAA patients being treated surgically, particularly among patients older than 80. As a result, the majority of patients admitted for rTAA now undergo surgical repair. TEVAR was associated with favorable outcomes compared to open repair, despite TEVAR patients being older and having more comorbidities. Due to the shift from open repair to TEVAR, and the shift from nonoperative treatment to TEVAR, overall mortality following rTAA admission declined over the study period.

The feasibility of endovascular repair in an acute setting for rTAA was first described in 1997.7 In 2004, Scheinert et al. reported a 30-day mortality of 9.7% among a cohort of 31 rTAA patients.10 Other series reported similar encouraging results, with mortality ranging between 3.1% and 24.6%. Comparing these outcomes to historic results for open repair with mortality of up to 45%,2, 6 Mitchell et al. concluded that TEVAR has become the treatment of choice for acute thoracic aortic surgical emergencies.13 However, comparative studies were unable to establish an absolute survival benefit of TEVAR over open repair.4, 11, 14 Jonker et al. evaluated morbidity and mortality after both operative approaches, and demonstrated that TEVAR was associated with a lower rate of perioperative adverse events in a multi-institutional study. Mortality, however, was not significantly reduced in TEVAR patients.4 These findings were supported by Patel et al. who also demonstrated a lower incidence of adverse events in a composite outcome measure.14

When Gopaldas et al. utilized the NIS in an effort to assess national rTAA outcomes on a national level for the years both treatments were available (2006–2008), neither mortality nor complication rates differed between TEVAR and open repair.16. Conversely, a recent study also utilizing NIS data up until 2008 found that TEVAR was associated with a reduction in perioperative mortality compared to open repair.15 In this study, however, open repairs as far back as 1998 were compared to TEVAR patients treated in 2008, which resulted in substantially higher in-hospital mortality after open repair of 53% compared to 29% in the Gopaldas study. In the present study using more recent data, we limited comparative analysis to data after the introduction of TEVAR. In contrast to Gopaldas et al., we found that perioperative morbidity and mortality following TEVAR was significantly lower compared to open repair. This difference is most likely due to the fact that the present study included more than four times the number of TEVAR cases, and the consequent increase in statistical power. Our results are in line with a retrospective analysis of Medicare beneficiaries in which Goodney et al. found significantly lower perioperative mortality in TEVAR patients compared to those undergoing open repair.21

Our study, similar to previous studies utilizing the NIS, is unable to assess long-term follow-up. However, previous reports have shown equivalent survival at 1- and 5-years, despite a substantially lower perioperative mortality after TEVAR.21–23 Patel et al. had similar 5-year findings in a cohort of 69 RTAA patients, although no significant differences in survival were observed in the perioperative period either.14

Mortality among patients undergoing nonoperative treatment was lower than expected, which is similar to previous studies using national registries for the identification of acute aortic pathologies.17 In our study, mortality among the nonoperative treatment group was approximately 60%, which is considerably lower compared to previous studies reporting rates exceeding 90%.1 This difference is most likely due to the fact that the NIS uses in-hospital mortality, while a substantial proportion of these patients are transferred to other hospitals, hospice facilities, or discharged to home. A subanalysis within the nonoperative treatment group demonstrated that 29% of nonoperatively treated patients were transferred to other hospitals, and 1% left against medical advice. Mortality among the remaining cohort was 87%, with 13% being discharged to home, with or without assisting care. This suggests the decrease in rTAA mortality through increased eligibility for surgery to be even greater than demonstrated in the present study.

While increases in the proportion of patients undergoing surgery were observed in all age groups, treatment changed most significantly among patients aged 80 and over after the introduction of TEVAR, with surgical treatment increasing by a factor of three since 2003–2004. This is similar to the increase in operative treatment among elderly abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) patients observed after the introduction of endovascular repair for AAA.24 These trends were also apparent after population-adjustment, with substantial increases in the number of surgical interventions per million, and a concurrent decline in in-hospital death. Aside from elderly patients, TEVAR also appeared to be preferred for patients with increased comorbidities, as evidenced by increased rates of coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease and hypertension among TEVAR patients compared to those undergoing open repair. This phenomenon has been demonstrated for elective abdominal and thoracic aortic surgery, and may explain the improved mortality trend for open repair due to patients with severe comorbidities now offered the endovascular alternative instead of invasive open repair.25, 26 Despite the improved outcomes associated with open repair in more recent years, a subanalysis for the years 2010–2012 demonstrated that TEVAR remains associated with favorable perioperative outcomes in this later period.

Previous studies have indicated that the introduction of endovascular repair and the consequent increase in elective repairs may have contributed to a decline in ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms.24, 27 In the present study, Figure 3 illustrates that for rTAA the decline in admissions and deaths started prior to the introduction of TEVAR. Nevertheless, the prevention of rupture through increased elective repair may very well have contributed to the decline ruptures and deaths in patients with TAA in the period thereafter. Other contributing factors may be the increased focus on familial screening programs and improved cardiovascular risk factor modification, including the decline in smoking in the US during the last decades.28, 29 Similar to previous studies assessing the role of endovascular repair, we found that TEVAR was more commonly performed in urban teaching hospitals.30–32 This was expected, as novel technologies and techniques such as TEVAR are typically introduced first to high volume academic centers.

This study has several limitations that should be addressed. First, since the NIS is an ICD-9 based database, it does not provide detailed operative or clinical data, including hemodynamic status at admission, time to surgery, and the use of conduits. Consequently, we are unable to assess the role of hemodynamics on operative selection, or establish the clinical implications of various patient and operative factors. Anatomic data are also lacking which may impact the choice of open repair vs. TEVAR and may also impact outcome. Additionally, previous studies have indicated that evaluation of surgical complications from administrative databases should be interpreted with caution, since documentation of non-fatal perioperative outcomes may be troubled.33–35 Because some complications may have been documented as comorbid conditions, these baseline characteristics could interfere with the adjusted analysis. Therefore, the multivariable model was tested without the inclusion of myocardial infarction and heart failure. No notable changes were observed with regard to the adjusted difference in mortality between TEVAR and open repair. Furthermore, only a limited number of diagnoses can be reported per patient. As a result, common comorbidities may be underreported in the sickest patients, leading to confounding for less severe cases. Since these protective risk estimates do not accurately reflect the association with mortality, we decided to exclude these variables from further analyses. Although the exclusion avoided unwanted interference with the outcomes, the underreporting of these comorbidities precluded purposeful selection as a means for constructing the multivariable model.

In conclusion, this study shows that TEVAR has been increasingly utilized since its introduction, and appears to be associated with significantly lower perioperative morbidity and mortality than traditional open surgical repair. In addition to replacing open repair as the dominant surgical approach for rTAA nationally, TEVAR has broadened treatment eligibility, with the majority of patients presenting with rTAA now undergoing operative intervention. As a result of the shift from open repair and nonoperative treatment to TEVAR, overall in-hospital mortality following rTAA admission has decreased in recent years.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the 2016 SCVS Annual Symposium (March 12–16, Las Vegas, NV)

References

- 1.Johansson G, Markstrom U, Swedenborg J. Ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysms: a study of incidence and mortality rates. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(6):985–8. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schermerhorn ML, Giles KA, Hamdan AD, Dalhberg SE, Hagberg R, Pomposelli F. Population-based outcomes of open descending thoracic aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(4):821–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford ES, Hess KR, Cohen ES, Coselli JS, Safi HJ. Ruptured aneurysm of the descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aorta. Analysis according to size and treatment. Ann Surg. 1991;213(5):417–25. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199105000-00006. discussion 25–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonker FH, Verhagen HJ, Lin PH, Heijmen RH, Trimarchi S, Lee WA, et al. Open surgery versus endovascular repair of ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5):1210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girardi LN, Krieger KH, Altorki NK, Mack CA, Lee LY, Isom OW. Ruptured descending and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(4):1066–70. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03849-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbato JE, Kim JY, Zenati M, Abu-Hamad G, Rhee RY, Makaroun MS, et al. Contemporary results of open repair of ruptured descending thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(4):667–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semba CP, Kato N, Kee ST, Lee GK, Mitchell RS, Miller DC, et al. Acute rupture of the descending thoracic aorta: repair with use of endovascular stent-grafts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8(3):337–42. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(97)70568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dake MD, Miller DC, Semba CP, Mitchell RS, Walker PJ, Liddell RP. Transluminal placement of endovascular stent-grafts for the treatment of descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(26):1729–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412293312601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doss M, Wood JP, Balzer J, Martens S, Deschka H, Moritz A. Emergency endovascular interventions for acute thoracic aortic rupture: four-year follow-up. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(3):645–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheinert D, Krankenberg H, Schmidt A, Gummert JF, Nitzsche S, Scheinert S, et al. Endoluminal stent-graft placement for acute rupture of the descending thoracic aorta. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(8):694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morishita K, Kurimoto Y, Kawaharada N, Fukada J, Hachiro Y, Fujisawa Y, et al. Descending thoracic aortic rupture: role of endovascular stent-grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1630–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amabile P, Rollet G, Vidal V, Collart F, Bartoli JM, Piquet P. Emergency treatment of acute rupture of the descending thoracic aorta using endovascular stent-grafts. Ann Vasc Surg. 2006;20(6):723–30. doi: 10.1007/s10016-006-9096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell ME, Rushton FW, Jr, Boland AB, Byrd TC, Baldwin ZK. Emergency procedures on the descending thoracic aorta in the endovascular era. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(5):1298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.05.010. discussion 302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel HJ, Williams DM, Upchurch GR, Jr, Dasika NL, Deeb GM. A comparative analysis of open and endovascular repair for the ruptured descending thoracic aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(6):1265–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilic A, Shah AS, Black JH, 3rd, Whitman GJ, Yuh DD, Cameron DE, et al. Trends in repair of intact and ruptured descending thoracic aortic aneurysms in the United States: a population-based analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147(6):1855–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopaldas RR, Dao TK, LeMaire SA, Huh J, Coselli JS. Endovascular versus open repair of ruptured descending thoracic aortic aneurysms: a nationwide risk-adjusted study of 923 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(5):1010–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong MS, Feezor RJ, Lee WA, Nelson PR. The advent of thoracic endovascular aortic repair is associated with broadened treatment eligibility and decreased overall mortality in traumatic thoracic aortic injury. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(1):36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.009. discussion 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ultee KH, Soden PA, Chien V, Bensley RP, Zettervall SL, Verhagen HJ, et al. National trends in utilization and outcome of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for traumatic thoracic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HCUP. Introduction to the NIS 2010. [updated July 2016; cited 2016 November] Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2010.jsp.

- 20.National cause-specific age adjusted mortality data on the occurence of death due to thoracic aortic injury between 1999–2013[Internet] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 06/29/2015] Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html.

- 21.Goodney PP, Travis L, Lucas FL, Fillinger MF, Goodman DC, Cronenwett JL, et al. Survival after open versus endovascular thoracic aortic aneurysm repair in an observational study of the Medicare population. Circulation. 2011;124(24):2661–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.033944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conrad MF, Ergul EA, Patel VI, Paruchuri V, Kwolek CJ, Cambria RP. Management of diseases of the descending thoracic aorta in the endovascular era: a Medicare population study. Ann Surg. 2010;252(4):603–10. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f4eaef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai ND, Burtch K, Moser W, Moeller P, Szeto WY, Pochettino A, et al. Long-term comparison of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) to open surgery for the treatment of thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(3):604–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.049. discussion 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schermerhorn ML, Bensley RP, Giles KA, Hurks R, O’Malley AJ, Cotterill P, et al. Changes in abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture and short-term mortality, 1995–2008: a retrospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2012;256(4):651–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4f91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lederle FA, Freischlag JA, Kyriakides TC, Matsumura JS, Padberg FT, Jr, Kohler TR, et al. Long-term comparison of endovascular and open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1988–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker KL, Shuster JJ, Martin TD, Hess PJ, Jr, Klodell CT, Feezor RJ, et al. Practice patterns for thoracic aneurysms in the stent graft era: health care system implications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(6):1833–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giles KA, Pomposelli F, Hamdan A, Wyers M, Jhaveri A, Schermerhorn ML. Decrease in total aneurysm-related deaths in the era of endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(3):543–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.067. discussion 50–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat. 2014;10(260):1–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, Bersin RM, Carr VF, Casey DE, Jr, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with thoracic aortic disease. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(14):e27–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meguid RA, Brooke BS, Perler BA, Freischlag JA. Impact of hospital teaching status on survival from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(2):243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park BD, Azefor N, Huang CC, Ricotta JJ. Trends in treatment of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: impact of endovascular repair and implications for future care. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(4):745–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.12.028. discussion 54–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ultee KH, Soden PA, Chien V, Bensley RP, Zettervall SL, Verhagen HJ, et al. National trends in utilization and outcome of thoracic endovascular aortic repair for traumatic thoracic aortic injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(5):1232–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawson EH, Louie R, Zingmond DS, Brook RH, Hall BL, Han L, et al. A comparison of clinical registry versus administrative claims data for reporting of 30-day surgical complications. Ann Surg. 2012;256(6):973–81. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826b4c4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bensley RP, Yoshida S, Lo RC, Fokkema M, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, et al. Accuracy of administrative data versus clinical data to evaluate carotid endarterectomy and carotid stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fokkema M, Hurks R, Curran T, Bensley RP, Hamdan AD, Wyers MC, et al. The impact of the present on admission indicator on the accuracy of administrative data for carotid endarterectomy and stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(1):32–8 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.