Abstract

Social defeat in rodents putatively can model hypohedonia. The present studies examined models for assessing hypohedonia-like behavior and tested the hypotheses that 1) individual differences in baseline reward sensitivity predict vulnerability, and 2) defeat elicits changes in pharmacological measures of striatal dopaminergic function. Male Wistar rats (n=142) received repeated defeat (3 “triad” blocks of 3 defeats) or control handling. To determine whether defeat influenced consumption of SuperSac (glucose-saccharin) over an isocaloric, less preferred, glucose solution, a 2-choice paradigm was used. To determine repeated defeat effects on the reinforcing efficacy of SuperSac, a progressive-ratio schedule of reinforcement was used. Amphetamine-induced locomotor activity (0.08 mg/kg, s.c.) was determined as a measure sensitive to striatal dopaminergic function. Defeat reduced SuperSac consumption during the first two triads—an effect seen in the third triad only in defeated rats with High vs. Low baseline SuperSac intake. The characteristic escalation in PR breakpoint for SuperSac normally seen in controls was absent in defeated rats, leading to a significant difference by the third triad. Defeat-induced blunting of the escalation in PR performance was greater in rats with High antecedent PR breakpoints and persisted 2.5 weeks post-defeat. Repeated defeat also blunted amphetamine-induced locomotion 13 days post-defeat. Thus, hypohedonic-like effects of social defeat were detected and accompanied by persistently attenuated striatal dopamine function. Early effects were seen for consumption of differentially-palatable solutions, and persistent effects were seen for the “breakpoint” motivational measure. The results implicate initial reward sensitivity as a risk factor for stress-induced hypohedonia.

Keywords: anhedonia or anhedonic or hypohedonia or reward, major depression or depressive or depressed, repeated or chronic defeat or social stress, motivation or volition or avolition, sugar or glucose or saccharin or SuperSac, amphetamine or dopamine reuptake inhibitor or dopaminergic

1. Introduction

Hypohedonia, the diminished ability to experience pleasure (contrasted from anhedonia, the inability to experience pleasure) is a characteristic feature of major depressive disorder, a negative symptom of schizophrenia, and a component of other neuropsychiatric disorders, such as drug withdrawal in addiction (Paterson and Markou 2007, Der-Avakian and Markou 2012, Der-Avakian et al. 2014). Disorders with hypohedonia are often associated with or precipitated by stress. For example, social stress in humans has been linked to major depression (Allan & Gilbert 1997, Gilbert et al. 2002), and, in rodent models, chronic stress can elicit putatively analogous hyphedonic-like behavior (Katz 1982, Willner et al. 1987). Hypohedonia is associated with altered reward processing; accordingly, stress alters reward processing circuitry (Der-Avakian et al. 2014, Der-Avakian & Markou 2012, Zacharko et al. 1983). The present work seeks to identify behavioral factors that differentiate individual vulnerability to the effects of stress on performance in consummatory and progression-ratio (PR) operant self-administration measures of gustatory hedonic value (Lundy 2008).

Social defeat can cause long-term hypohedonic-like effects in rodents (Der-Avakian et al. 2014, Von Frijtag et al. 2000). The resident-intruder model of social defeat, in particular, involves interaction between a dominant, aggressive male resident rat and an intruder rat, where the intruder is rapidly defeated and submits to a supine position (Miczek et al. 2008). There are marked individual differences in the susceptibility vs. resilience to develop hypohedonic-like behavior following defeat (Der-Avakian et al. 2014). For example, while all rats exposed to chronic social defeat had elevated ICSS reward thresholds on days that they experienced defeat, only a subset of these rats continued to show elevated ICSS thresholds up to 20 days after defeat (Der-Avakian et al. 2014). Analogously, in humans, following the acute stress of a mild electrical shock, only certain (stress-responsive) individuals develop reduced reward sensitivity (Berghorst et al. 2013). The basis for such differences are unclear, but antecedent differences in reward circuit function and/or stress reactivity have been proposed (Berghorst et al. 2013). One study showed that rats with high locomotor responses to a novel environment also had greater basal sucrose consumption, which was decreased following social defeat; in contrast, low locomotor responder rats showed no effect of defeat on sucrose consumption (Hollis et al. 2011). Perhaps relatedly, stress is known to have opposite effects on subsequent alcohol intake in rats, depending on their baseline alcohol preference (Volpicelli et al. 1990).

Many studies of chronic stress have utilized rodent’s consumption of and/or preference for sweet solutions as a measure of gustatory hedonic behavior. Such procedures, popularized in the context of chronic mild stress models of depression (Katz 1982, Willner et al. 1987, Muscat and Willner 1992, Papp 1991), were extended to chronic social stress models (Tamashiro et al. 2007, Herzog et al. 2009), including repeated defeat (Rygula et al. 2005). The most common procedures involve 2-choice access of a dilute sucrose solution (0.9%–1% sucrose) vs. water (Muscat & Willner 1989). A frequent criticism is that reduced intake of the caloric, sweet solution may simply be due to stress-induced reductions in body weight (Forbes et al. 1996, Matthews et al. 1995), which led some investigators instead to assess the intake of non-caloric saccharin vs. water, with inconsistent results (Harris et al. 1997, Grønli et al. 2005, Hatcher et al. 1997, Harkin et al. 2002). To our knowledge, all existing procedures have involved consumption of a sweet solution vs. water, in which only the former contained and/or “signaled” energy, rendering them vulnerable to the body weight criticism. Towards mitigating this alternative interpretation, in the present study, we instead sought to determine whether defeat influences the acceptance and/or preference of a preferred sweet solution over an isocaloric, but less preferred, sweet solution. For this, the 2-choice intake of highly preferred glucose-saccharin mixture (Valenstein et al. 1967), so-called SuperSac, over glucose was compared. In addition, the present study tested the hypothesis that individual differences in baseline reward sensitivity, as defined by initial levels of SuperSac intake, would prospectively predict the individual vulnerability to defeat effects on performance.

While much research has examined the effects of chronic stress, including repeated defeat, on reward consumption, less has examined the effects of social defeat on incentive motivation (Barnes et al. 2013). Progressive ratio (PR) operant responding (Hodos 1961), in which response requirements for successive reinforcers increase exponentially with each reinforcer earned, is a frequently used paradigm for assessing volition (Barnes et al. 2013, Stafford et al. 1998, Arnold & Roberts 1997). Therefore, the present study also sought to determine the time course and persistence of repeated defeat effects on the reinforcing efficacy of SuperSac, as defined by breakpoints on a PR schedule of reinforcement. We also tested the hypothesis that individual differences in antecedent incentive motivation for the SuperSac would predict individual vulnerability to effects of repeated defeat on volition.

In terms of understanding the neurobiological substrates of defeat effects, acute stress is known to alter the striatal circuitry that subserves reward (Porcelli et al. 2012), and dopaminergic transmission previously has been shown to mediate the long-term effects of stress on reward (Montagud-Romero et al. 2016, Huang et al. 2016). Social defeat in adolescence leads to long-term changes in dopaminergic pathways studied in adulthood (Watt et al. 2014, Burke et al. 2013), a finding that could be interpreted as developmental in nature. Whether social defeat experienced in adulthood similarly impacts striatal dopamine function, especially past the acute post-defeat stage is uncertain. To determine this, we investigated the effects of social defeat in a model highly sensitive to changes in striatal dopamine function: amphetamine-induced locomotor activity (Vaccarino et al. 1986, Papp et al. 1993).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

Adult, male Wistar rats (n = 142; 200–225 g on arrival; Charles River, Raleigh, NC, USA) were “intruders” in the resident–intruder defeat models of the present studies. Subjects were single-housed in wire-topped, plastic cages (48×27×20 cm) in a 12-h light/dark (08:00 h lights off), humidity- (60%) and temperature-controlled (22 °C) vivarium. Larger adult, male Long-Evans rats (450–700 g on arrival) were housed in enclosures (48×69×50 cm) with sawdust- covered, stainless steel floors and were territorial “residents” in the defeat model. Each resident used (n = 18) was stably housed with an adult, female Wistar rat (n = 18) that had received electrocauterization of the uterine coils under isoflurane anesthesia (1%–3% in oxygen) to prevent pregnancy. Food and water were available ad libitum unless stated otherwise. Procedures adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Scripps Research Institute.

2.2 Social Defeat

The resident-intruder procedure for social defeat was used in all experiments (Fekete 2009). Due to the strain’s propensity for territoriality and dominance behavior across the lifespan Long-Evans rats were used as residents following the precedent of Miczek and colleagues (Blanchard et al., 1984, Miczek, 1979; Tornatzky and Miczek, 1993, 1994), who developed and characterized the resident–intruder model. Each resident was housed with a sexually mature female Wistar rat for 1 month to promote territorial behavior. Intruders were from the less aggressive Wistar strain, which shows somewhat less social agonistic behavior, (Scholtens and Van de Poll, 1987; Schuster et al., 1993). To potentiate dominance behavior, residents were exposed to “training” intruders—post-pubertal, smaller male Wistar rats—for 12 days before experimental studies. After removing the female from the cage, residents were exposed to different training intruders once per day, for 3 consecutive days at a time, with exposure lasting until the intruder submitted. Training intruders were removed from the home cage immediately after defeat, and females were returned to the cage. Defeat was defined as adoption of a submissive, supine posture by the intruder rat (Miczek, 1979; Tornatzky and Miczek, 1993). Training reduces the mean latency by which residents later achieve submissions over experimental intruders to <90 s and thereby reduces the duration of physical conflict that residents require to attain defeats. Potential residents that injured intruders during training, did not achieve 3 consecutive days of defeat, or had mean defeat latencies >120 s were excluded from the study, yielding the 18 residents from the present studies. Training was conducted during the animals’ dark cycle under red lighting.

On test days, the female mate was removed from the cage before placing the intruder within the enclosure. Intruders were introduced and, upon their submission, were then placed inside a protective wire-mesh enclosure (20×20×32 cm) within the resident’s home cage. Intruders remained in the enclosure for 30 min to provide further psychosocial threat. The wire enclosure prevented physical injury, but allowed auditory, olfactory, visual and limited physical contact (mouth/nose). For all experiments, defeat tests were conducted in three triads. Each triad consisted of once daily defeat tests for three consecutive days; triads were spaced by 3–5 non-test days unless otherwise noted. Non-defeat controls were handled on test days and returned to their homecage without food for 30 min, corresponding to the duration of the “threat” period.

2.3 Expt. 1: Effects of repeated social defeat on voluntary “SuperSac” (vs. glucose) consumption

In lieu of water, rats (n = 16) were maintained with 2-bottle choice, ad libitum access to a highly palatable “SuperSac” solution (Valenstein et.al. 1967), consisting of 3% glucose and 0.125% saccharin (w/v) in water, vs. an isocaloric glucose solution (3% w/v in water). After 14 days of acclimation, consumption appeared stable (<10% variation over 5 days), and rats were assigned to defeat vs. control conditions matched for baseline SuperSac intake with Day 14 intake defined as “baseline” performance. Rats were then subjected to the repeated social defeat paradigm (n = 8, 3 “triads” of daily defeat [9 total defeats] with each triad spaced by 3–5 days) or served as non-defeated controls (n = 8). SuperSac and glucose consumption were measured daily, and preference ratios (SuperSac/(SuperSac+Glucose)) were calculated. Defeats were performed 7–9 hours following dark cycle onset, and 24-hour intake measurements began immediately following defeat.

2.4 Expt. 2: Effects of repeated social defeat on the reinforcing efficacy of SuperSac

In lieu of water, all rats (n = 44) received ad libitum 2-choice access to SuperSac vs. isocaloric glucose in their home cages for 12 days, prepared as above. Rats were then returned to standard water access in the home cage and were allowed to acquire operant self-administration of SuperSac. For operant self-administration, rats were tested individually in Plexiglas test cages (22 × 22 × 35 cm). Cages had a wire-mesh floor and were located in ventilated, sound-attenuating enclosures equipped with a 1.1 W miniature bulb synchronized to the vivarium’s light/dark cycle. Rats could make lever press responses from an “active” lever on the wall of the test cage to obtain delivery of 0.100 ml aliquots of solution governed by a solenoid valve (W.W. Grainger, Lincolnshire, IL) into an adjacent reservoir; depression of a second “inactive” lever resulted in no scheduled consequences. Responses were recorded by an IBM PC-compatible microcomputer with 10 ms resolution.

For acquisition, rats first received two-hour fixed-ratio (FR) 1 operant responding sessions once daily, 3–5 times per week until they attained 200 responses per session. Response requirements were then increased to FR3 (and, for 22 of the rats due to experimenter error, FR10) which involved 11–15 sessions before all rats were switched to a progressive ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement, in which the lever press requirement to obtain a reinforcer exponentially increased with each reinforcer earned per the formula 5*exp((n−1)*0.15)−5 with the progression, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 17, 21, 25, 30… (where n is the number of the reinforcer). Breakpoint was defined as the maximum ratio of lever presses per reinforcer that a rat received without reaching the 14-minute maximum inter-reinforcer interval. Rats received 6–14 PR sessions (180 min max) once daily until group performance during the preceding 5 days varied less than 20% from the mean of those days to establish a baseline PR breakpoint. Potential differences in training history or baseline performance were controlled for in analysis by covarying for baseline PR breakpoint and training cohort. Rats continued once-daily PR sessions while beginning the social defeat paradigm (n = 23) or serving as controls (n = 21) as described. PR sessions took place 23–24 hours after defeat sessions or control handling. To determine the persistence of defeat effects, a subset of rats (n=22; defeated=12, control=10) then were deprived of SuperSac access for 2.5 weeks before receiving a final PR session (with no additional defeat).

2.5 Expt. 3: Effects of repeated social defeat on amphetamine-induced locomotor activity

Five days after completion of the social defeat paradigm, repeated defeat and control rats were habituated to previously described photocell cages for measuring locomotor activity (Izzo et al. 2005) for 3 h/day on 3 consecutive days under infrared lighting. Each of the 16 cages measured 20 × 25 × 36 cm, and was made of wire mesh. Two infrared photocell beams were situated across the long axis 2 cm above the floor. Interruption of a beam was registered by a computer situated in an adjoining room. Background noise was provided by a white noise generator.

On the test day (day 8), rats were placed in the test cages for 60 min (for pre-acclimation) and then injected s.c. with 0.08 mg/kg d-amphetamine, which elicits mesolimbic dopamine-dependent locomotor activity (Vaccarino et al. 1986) or saline. Five days later (day 13), each rat was again habituated for 60 minutes and received the other treatment (d-amphetamine or saline) in counter-balanced fashion. To reduce potential order effects, rats were assigned to receive their initial treatment, within Defeat grouping, matched for total locomotor activity during the first hour of the third habituation day. Locomotor activity was recorded as crossovers (successive interruptions of the two photobeams) for 90 min following each injection.

2.6 Statistical Analyses

Defeat-induced changes in SuperSac intake and PR breakpoint were analyzed using repeated measures 2-way ANOVA with Defeat (Defeat vs. Control) as a between-subjects factor and Triad (1st, 2nd or 3rd block of defeats) as a within-subject factor, covarying for baseline performance (Zhang et al. 2014). Bonferroni-corrected pairwise tests were used to compare performance within specific triads. Because variance of defeated groups differed across defeat triads, the results suggested individual differences in the response to repeated defeat, as expected. To determine whether initial performance differentiated the response to defeat, subjects were defined as initially High vs. Low consuming/responding based on median split of baseline (pre-defeat) performance. Defeat-induced changes then were analyzed differentiating between High vs. Low baseline performance. To facilitate illustration of these follow-up results, data were calculated as % of baseline performance. Follow-up paired t-tests also were used to compare SuperSac consumption during the defeat triads to baseline values. Group differences were assessed by Student’s unpaired t-tests to determine effects of repeated defeat specifically in High vs. Low responders. Differences in preference ratios in the SuperSac intake study were determined by unpaired t-tests. Change in glucose consumption by the final defeat triad was calculated as percent consumption relative to baseline and analyzed by unpaired t-test. Change in body weight, calculated as the difference between the final triad and baseline, was analyzed by unpaired t-tests for defeated vs. control rats. To determine whether rats with a defeat history had increased motor activity in a novel environment, we used a one-tailed t-test. To assess the effect of amphetamine (vs. vehicle) treatment on locomotion in defeated or non-defeated animals over time, we utilized a repeated-measures 3-way ANOVA with Defeat as a between-subjects factor and Drug and Time as within-subjects factors. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA), R (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria), and SPSS 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

3. Results

3.1 Expt. 1: Effects of repeated social defeat on voluntary “SuperSac” (vs. glucose) consumption

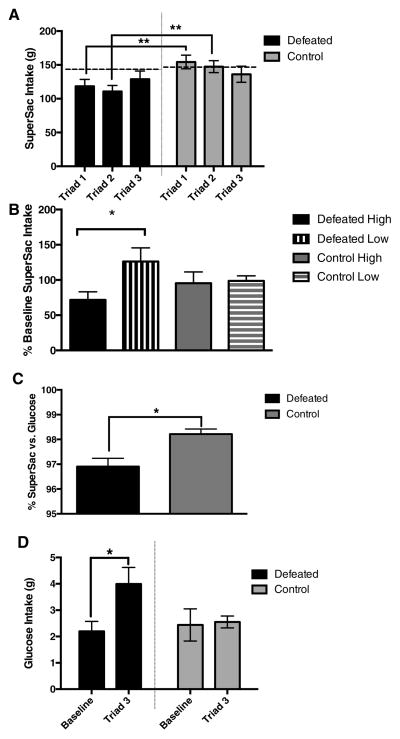

Defeat significantly reduced SuperSac consumption as compared to non-defeated controls (Defeat main effect F(1,13) = 7.562, p = 0.017). Although the Defeat X Triad interaction did not reach significance, inspection of Figure 1A suggested that the effects of repeated defeat on SuperSac intake did not robustly persist into the third triad. Therefore, and also because variance between triads was unequal, we performed Bonferroni-corrected comparisons for each triad and observed that defeated rats consumed significantly less SuperSac compared to non-defeated controls only during the first (t(13) = 3.716, p = 0.003) and second triads (t(13)=3.793, p=0.002). By triad 3, mean SuperSac intake was no longer reduced in defeated animals (t(13)=0.760, p=0.469). Correspondingly, within the defeated animals, there was a significant reduction in SuperSac consumption relative to baseline during triad 1 (t(7)=2.935, p=0.0109) and triad 2 (t(7)=2.223, p=0.0308), but not triad 3 (t(7)=0.092, p=0.5355). In contrast, performance of controls did not differ significantly from baseline during any of the triads (Fig 1A). Intake did not differ between defeated and control animals on non-defeat days (data not shown). As Figure 1B shows, however, when rats were distinguished between those High vs. Low for baseline SuperSac consumption, High baseline rats did still show significantly less SuperSac consumption compared to Low baseline rats in triad 3 (t(6)=2.419, p=0.026) with a trend also for reduced intake from baseline (p=0.07).

Figure 1.

A. Defeat significantly reduced SuperSac consumption as compared to non-defeated controls (Defeat main effect). By Bonferroni-corrected comparisons for each triad, defeated rats consumed significantly less SuperSac compared to both their own baseline consumption (indicated by dashed line) and non-defeated controls only during the first and second triads. B. Repeated defeat reduced SuperSac consumption of High compared to Low baseline rats during the third triad. C. In triad three, defeated rats showed decreased preference ratios for SuperSac (vs. isocaloric glucose) compared to control rats. D. By the third triad, intake of isocaloric glucose significantly increased, relative to baseline, in defeated rats but not non-defeated controls. * p< 0.05, ** p<0.01

During the final triad, defeated rats showed small, but statistically significant, decreases in preference ratios for SuperSac (vs. isocaloric glucose) as compared to control rats (t(14)=3.3333, p= 0.0049)(Fig 1C and Supplementary Table 1). This difference was not pre-existing in baseline preference ratios (t(14)=0.3215 p=0.75). The decreased preference ratios reflected that, by the third triad, the low levels of isocaloric glucose intake significantly increased ~2-fold, relative to baseline, in defeated rats (t(7)=2.103, p=0.0368), an effect absent in non-defeated controls (t(7)=1.29, p=0.8810)(Fig. 1D).

Defeat did not alter total fluid consumption (SuperSac + Glucose) as a main effect (F(1,14)=0.08830, p=0.7707) or in interaction with Triad/Time (F(1,14)=0.011, p=0.9176) (data not shown). No significant defeat- or baseline-related group differences were observed on change in body weight (Defeat: F(1,12)=0.604, p=0.45, High/Low Baseline main effect: F(1,12)=0.3233, p=0.58, Interaction: F(1,12)=0.07916, p=0.78). Furthermore, change in body weight did not correlate significantly with intake or preference in defeated or control rats (not shown).

3.2 Expt. 2: Effects of repeated social defeat on the acquired reinforcing efficacy of SuperSac

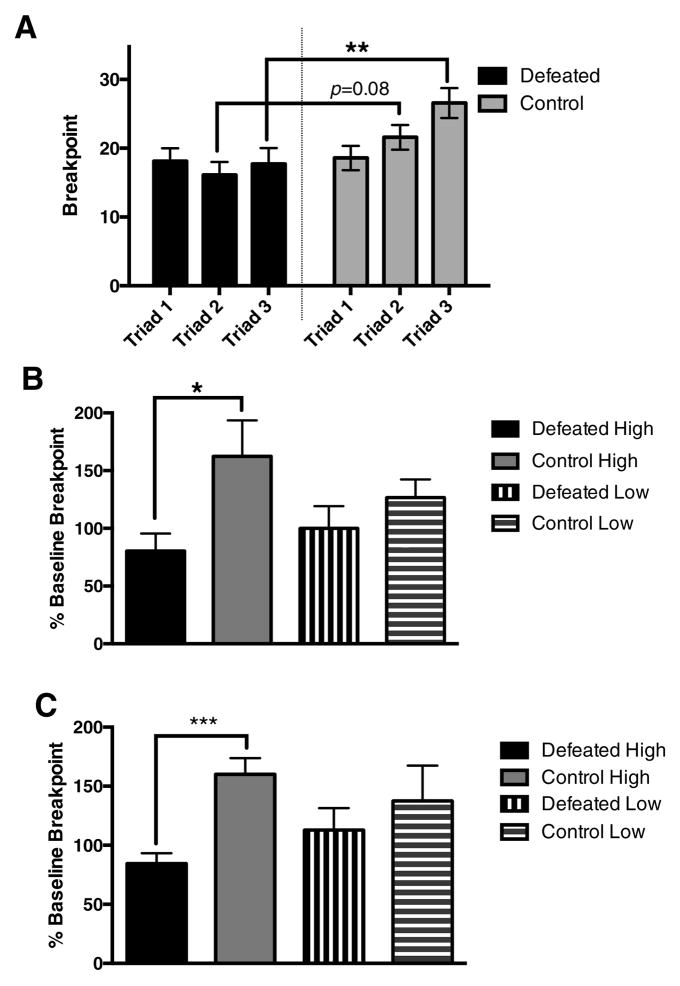

A significant Defeat X Triad linear contrast interaction (F(1,37)=4.734, p=0.036) and main effect of Defeat (F(1, 37)=6.912, p=0.012)), indicated that performance of defeated and control subjects differed across the 3 triads in a time-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 2A, controls normally show escalation of PR breakpoints for SuperSac across the 18-day test period (t(40)=2.8488, p=0.0069). This increase in performance of controls was observed in all three independent cohorts that were tested in the model. Defeated subjects, in contrast, failed to show this increase (t(44)=0.1348, p=0.8934). As a result, PR breakpoints of defeated and control rats did not differ during the first triad of defeats (t(37)=0.154, p=0.88), but, by triad 2, defeated rats tended to be lower than controls (t(37)=1.802, p=0.0797), and by triad 3, their performance was significantly lower than that of controls (t(37)=2.919, p= 0.00595) (Fig 2A).

Figure 2.

A. Defeat significantly blunted the increase in PR breakpoints for SuperSac compared to non-defeated controls (Defeat main effect, Defeat X Triad linear contrast interaction). The blunting of PR breakpoints becomes more evident across triads as controls increase, showing mild blunting by triad 2, and significant blunting by triad 3. B. Defeat only blunted the PR breakpoint increase during triad three, relative to baseline, in High, but not Low, rats as compared to their respective controls C. After 2.5 weeks of SuperSac deprivation, upon renewed access to SuperSac, defeated rats that had an initially High baseline breakpoint persisted in showing blunted breakpoint increase as compared to their controls. * p< 0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001

When rats were categorized as High or Low in baseline PR breakpoints, defeat only blunted the PR breakpoint increase from baseline, in High rats as compared to their respective controls (t(9)=2.5, p=0.0388), an effect that was not significant in Low rats (t(9)=0.5118, p=0.6211) (Fig 2B). After their final defeat, all rats were deprived of SuperSac access (and PR sessions) for 2.5 weeks. Upon renewed access to SuperSac, defeated rats that had an initially High baseline breakpoint persisted in showing blunted breakpoints as compared to their escalated controls (t(9)=4.807, p=0.001), an effect that was not significant in Low baseline rats (Fig 2C).

3.3 Expt. 3: Effects of repeated social defeat on amphetamine-induced locomotor activity

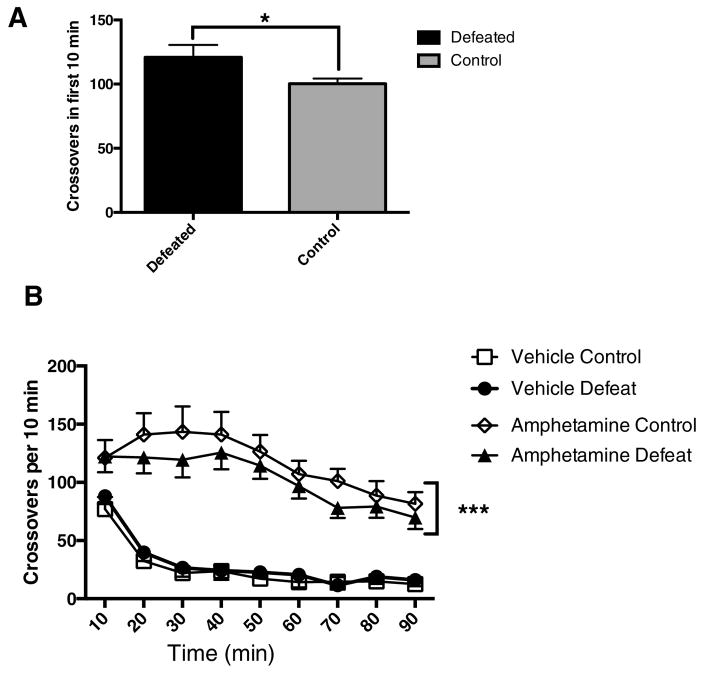

Locomotor activity

Prior to any drug or vehicle treatment, Figure 3A shows that rats that had previously experienced repeated defeat showed increased initial locomotion (10 min) when placed in the locomotor activity chambers for the first time compared to controls (Welch-corrected t(17.37)=1.981, p=0.0318) (Fig 3A). Subsequently, on the test day (day 8 or 13), as Figure 3B shows, a significant Defeat X Amphetamine interaction (F(1, 544)=10.99 p=0.00098; also Defeat: F(1, 544) =6.847, p= 0.0091) reflected that defeated rats showed similar activity to non-defeated controls under saline conditions, but consistently showed less locomotion than non-defeated controls following amphetamine injection. Descriptively, this difference was seen during each of the 9 observation time bins, a difference unlikely to occur by chance (P(X=9)= 0.00195). As expected, main effects of Amphetamine (F(1,544)= 579.953, p<2e-16) and Time (F(1,544)=185.634, p<2e-16) were seen as well.

Figure 3.

A. Prior to drug or vehicle treatment, rats that had previously experienced repeated defeat show increased initial locomotion when placed in the locomotor activity chambers for the first time compared to controls. B. A significant Defeat X Amphetamine interaction reflected that defeated rats showed similar activity to non-defeated controls under saline conditions but consistently showed less locomotion than non-defeated controls following amphetamine injection. * p< 0.05, ***p<0.001

4. Discussion

The present results show that the effects of repeated social defeat on consummatory and operant performance measures of gustatory hedonic value can be detected in modified behavioral models that require little (choice SuperSac intake) or readily available specialized equipment (PR breakpoints) and suggest that greater pre-existing reward sensitivity may associate with greater vulnerability to the effects of defeat. Amphetamine-induced locomotion, a behavior thought to be mediated by striatal dopamine-D2 receptor signaling (Papp et al. 1993), was altered by repeated defeat, consistent with the suggestion that hypohedonic-like behavior (Der-Avakian and Markou 2012) and the effects of repeated defeat (Krishnan et al. 2007, Chaudhury et al. 2013) are associated with altered mesolimbic dopamine functioning. In the consummatory measure, acute effects were seen even during the first triad, but were no longer seen on a mean group basis after repeated triads. Group effects of defeat on PR breakpoint performance were not seen initially, but manifested later as defeated subjects failed to develop the increased willingness to work for SuperSac normally shown by control subjects. This behavioral difference persisted through the post-defeat period similar to the blunting of amphetamine-induced locomotion. The collective results contribute to measuring and understanding the neurobiological basis, and individually-susceptible development of hypohedonic-like behavior following repeated stress.

4.1 Consumption and volition models of gustatory reward value

Previous putative models of stress-induced hypohedonia based on sweet solution intake involved animals choosing between a dilute sugar solution (typically sucrose) vs. water (Muscat & Willner 1989) and were criticized for their inability to dissociate reduction of sucrose consumption from stress-induced decreases in body weight (Forbes et al. 1996, Matthews et al. 1995). Some studies turned to saccharin vs. water as an alternative, but with inconsistent results (Harris et al. 1997, Grønli et al. 2005); as with sucrose, a similar concern that only the sweet solution “signals” energy content also still complicates interpretation of intake of saccharin vs. (non-sweet) water. Towards addressing these concerns, the present model involved 2-choice intake of isocaloric, sweet solutions, but where one solution (SuperSac) was more highly consumed and preferred over the other (Valenstein et al. 1967). Social defeat had fairly immediate effects to decrease daily consumption of the highly palatable SuperSac solution, but not isocaloric glucose, during the first triad of defeat sessions. This effect was still present during the second triad, but was no longer evident on an average basis by the third triad of defeats. Still, defeated rats did on average show a small, but statistically significant, decrease in their preference ratio for SuperSac over glucose by the third defeat triad, an effect associated with a ~2-fold increase in the low levels of intake of (less preferred) glucose.

SuperSac consumption previously was shown to be reduced in a repeated footshock paradigm that did not influence consumption of a sugar solution, suggesting that SuperSac might be a more sensitive measure of detecting hypohedonic-like effects of repeated stress (Dess and Choe 1994). Rather than inducing hypohedonia, an alternative interpretation of both findings is that repeated stress increases the aversive taste properties of saccharin. Both the present and previous studies of SuperSac implicate altered mesolimbic dopamine function in the effects of stress. It remains to be determined directly whether these changes are modulating the appetitive or aversive properties of SuperSac.

The present study, by comparing intake directly to isocaloric glucose, mitigates the concern that the effects of repeated stress on consumption of the palatable SuperSac solution are related to the caloric value of the tastant, unlike criticisms that have been levied against 2-choice comparisons of sugar solutions vs. water (Forbes et al. 1996, Matthews et al. 1995). Also consistent with the intent to dissociate the hypohedonic-like behavior from body weight changes in the present study, defeat did not elicit significant reductions in body weight during the time course studied, and body weight change in the defeated group did not correlate with changes in SuperSac intake or preference ratios.

In contrast to the early but, typically diminishing, effects of repeated defeat on homecage SuperSac intake, in a distinct paradigm, defeated rats did not initially show differences in PR breakpoint during the first defeat triad compared to control animals, suggesting that social defeat was not acutely affecting volition. Rather, defeat prevented the escalation in progressive ratio performance for the highly reinforcing solution that normally develops in unstressed control animals. This steady increase in control performance was seen in each cohort of rats tested and occurred despite evidence of acquisition of fixed-ratio self-administration behavior before the start of testing (FR1 responses: mean=294; FR3 responses; mean=286). Thus, it seems unlikely that defeat was interfering with the acquisition of self-administration behavior per se. Rather, one interpretation is that the restricted nature of PR access led to increased willingness to work for SuperSac by control subjects, expressed as steadily increasing PR responding, similar to what occurs with limited access to palatable high-fat (Wojnicki et al. 2010) or high-sucrose (Spierling et al. 2016) food. Because PR performance of defeated rats did not decrease from their baseline performance, the results do not support an avolition interpretation of differences. Rather, defeated subjects did not show the invigoration of performance for the reinforcer normally seen in controls, leading to a marked group difference by the third defeat triad. To an observer unaware of initial performance, this might be misinterpreted as avolition. The PR method of assessing motivation, notably, is not without critique, and each reinforcer earned may be (differentially) modulating the hedonic state of the animal, and having a confounding effect on the future responses (Arnold & Roberts 1997).

The basis for the different time courses of defeat effects in the consummatory vs. PR models should be interpreted cautiously. Although both experiments included an acclimation period where baseline SuperSac was measured, there were differences in the subsequent training period for operant behavior in the PR experiment. Independent of one another, effects were seen immediately in the consummatory paradigm and in a delayed manner in the PR performance measure, perhaps due to increasing valuation.

The present results are consistent with a recent study where defeated mice underperformed on PR tests for sucrose pellets following chronic social defeat (Bergamini et al. 2016). However, the results differ from a report that social defeat led to persistent increases in operant performance for sucrose solution on a PR schedule (Riga et al. 2015). In the latter study, however, the acquisition of operant responding took place after the defeat exposure, such that stress may have influenced conditioning per se or the learned reward value of the reinforcer.

4.2 Baseline reward motivation and defeat outcome

Rats with higher baseline performance in both the SuperSac intake and PR breakpoint studies were disproportionately more sensitive to the effects of repeated defeat and/or showed more lasting effects. Rats that were identified as being High SuperSac drinkers at baseline continued to show significantly reduced intake during the second and third defeat triads, unlike Low SuperSac drinkers. Defeated rats that had High PR breakpoints at baseline showed larger blunting of breakpoints relative to their respective controls than did defeated Low baseline breakpoint rats. The blunted breakpoint in defeated High baseline rats persisted 2.5 weeks after the final defeat.

Several previous studies support the possibility raised here that greater baseline reward sensitivity may predict increased vulnerability to stress-induced hypohedonia. First, rats that were high in their exploratory response to a novel environment, which has been conceptualized as being related to increased sensation- or reward-seeking and decreases in response to acute social stress (Meerlo et al. 1996), showed defeat-induced decreases in reward sensitivity to a sucrose solution, whereas rats that showed initially low behavioral responses to novelty did not (Hollis et al. 2011). Second, studies in humans have looked at striatal responses to reward as predicting subsequent risk for developing depressive-like symptoms. Relevant to the present findings, one study found that adolescents with greater baseline ventral striatal activation response to “hedonic” rewards showed increased risk for subsequent development of depressive-like symptoms (Telzer et al. 2014). Together, the studies highlight a need for further understanding of the predictive nature of initial reward sensitivity on subsequent risk for stress-induced depressive-like outcomes. Moreover, it needs to be better understood which predictive phenotypes observed in adolescents are only developmental in nature (Luking et al. 2016, Corral-Frías et al. 2016) vs. which are predictive of depressive-like symptoms across the lifespan.

4.3 Repeated defeat alters behavioral measures of striatal dopamine function

Repeated defeat blunted amphetamine-induced locomotion, a behavioral measure sensitive to striatal dopamine function (Papp et al. 1993). Previously, Burke and colleagues showed that animals that were defeated as adolescents showed lasting blunting of amphetamine-induced locomotion (Burke et al., 2010; Burke et al. 2013). The unique reactivity of dopaminergic transmission in adolescence can play a key role in vulnerability for depressive symptoms in adulthood (Telzer 2016), which raised questions as to whether the effects of defeat in adolescence were developmentally-specific. The present study shows that such effects are not (only) developmental in nature, but also occur if animals are defeated as adults. Because we saw an effect at 13 days after defeat, we propose that future work should assess course and causal role of dopaminergic function post-defeat over an extended time course as in our PR experiment. Additionally, further investigation is warranted to determine if there are any antecedent predictors of defeat-induced blunting of amphetamine-induced locomotion.

Several other findings have implicated changes in dopamine function, including D2 receptor-modulated circuitry as found here, in the effects of repeated defeat. Differences in susceptibility to engage in depression-like behavior following repeated social defeat may be mediated by the dopamine D1 receptor (Huang et al. 2016). Pre-defeat treatment with raclopride, a D2-receptor antagonist, or SCH 23390, a D1-receptor antagonist, blocked defeat-induced potentiation of conditioned place preference for cocaine, implicating signaling at both receptors in the pathogenesis of social defeat effects (Montagud-Romero et al. 2016).

4.4 Repeated defeat increased behavioral activity in novel contexts

Consistent with a previous adolescent defeat study (Burke et al. 2010), our drug-naïve defeated animals showed increased locomotion during the first ten minutes of ever being placed in the novel test chamber. Although freezing, immobility, and decreased activity are common anxiogenic-like responses in a novel environment (Koob et al. 1993) or with fear conditioning (van Dijken et al. 1992), increased activity also can be observed as part of classic “fight or flight” panic/fear-like responses, in which escape from a present threat is sought (or, similarly, in relation to anticipated threats). Recent studies suggest that different neuronal ensembles subserve competing immobility/freezing-type responses vs. excitation of body movement in response to perceived threats (Halladay and Blair 2015), with the infralimbic cortex mediating competition between the two responses (Halladay and Blair 2016). Similarly, electrical stimulation of the dorsomedial and dorsolateral periaqueductal grey differentially mediate defensive freezing vs. escape behavior (Vianna et al. 2003). The present results suggest that repeated defeat may bias behavior towards excitation of movement in novel contexts, perhaps consistent with a hyperalert, “preparedness” for flight.

5. Conclusion

The present results show that motivationally-relevant effects of repeated social defeat can be detected in simple, modified behavioral models that use consumption and progressive ratio self-administration measures and suggest the hypothesis that pre-existing greater reward sensitivity is associated with greater vulnerability to the effects of defeat. Acute effects were observed in consummatory behavior. Defeat blunted the increase in progressive ratio performance for a highly reinforcing sweet solution that normally develops in control animals, an effect still evident more than 2 weeks post-defeat. Defeat-induced blunting of amphetamine-induced locomotion suggests persistently attenuated mesolimbic dopamine functioning. Further neurobiological and pharmacological investigations may translate to novel treatment approaches for stress-induced mood disturbance.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Pre-existing reward sensitivity is associated with vulnerability to defeat

Acute effects of social defeat were observed in consummatory behavior

Defeat blunts progressive ratio responding for a reinforcing sweet solution

Defeat may persistently attenuate mesolimbic dopamine functioning

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 DK26741 and R01 DK64871 and by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award P50 AA06420 as well as the Pearson Center for Alcoholism and Addiction Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

The authors thank Dr. George Koob for early intellectual and financial contributions to this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Allan S, Gilbert P. Submissive behaviour and psychopathology. Br J Clin Psychol. 1997;36(Pt 4):467–488. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold JM, Roberts DC. A critique of fixed and progressive ratio schedules used to examine the neural substrates of drug reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57(3):441–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes SA, Der-Avakian A, Markou A. Anhedonia, avolition, and anticipatory deficits: assessments in animals with relevance to the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(5):744–758. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergamini G, Cathomas F, Auer S, Sigrist H, Seifritz E, Patterson M, Gabriel C, Pryce CR. Mouse psychosocial stress reduces motivation and cognitive function in operant reward tests: A model for reward pathology with effects of agomelatine. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(9):1448–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berghorst LH, Bogdan R, Frank MJ, Pizzagalli DA. Acute stress selectively reduces reward sensitivity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:133. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard RJ, Flannelly KJ, Layng M, Blanchard DC. The effects of age and strain on aggression in male rats. Physiol Behav. 1984;33(6):857–861. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke AR, Forster GL, Novick AM, Roberts CL, Watt MJ. Effects of adolescent social defeat on adult amphetamine-induced locomotion and corticoaccumbal dopamine release in male rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burke AR, Renner KJ, Forster GL, Watt MJ. Adolescent social defeat alters neural, endocrine and behavioral responses to amphetamine in adult male rats. Brain Res. 2010;1352:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW, Ferguson D, Tsai HC, Pomeranz L, Christoffel DJ, Nectow AR, Ekstrand M, Domingos A, Mazei-Robison MS, Mouzon E, Lobo MK, Neve RL, Friedman JM, Russo SJ, Deisseroth K, Nestler EJ, Han MH. Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493(7433):532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature11713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corral-Frias NS, Nadel L, Fellous JM, Jacobs WJ. Behavioral and self-reported sensitivity to reward are linked to stress-related differences in positive affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;66:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Der-Avakian A, Markou A. The neurobiology of anhedonia and other reward-related deficits. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35(1):68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Der-Avakian A, Mazei-Robison MS, Kesby JP, Nestler EJ, Markou A. Enduring deficits in brain reward function after chronic social defeat in rats: susceptibility, resilience, and antidepressant response. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(7):542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dess NK, Choe S. Stress selectively reduces sugar + saccharin mixture intake but increases proportion of calories consumed as sugar by rats. Psychobiology. 1994;22:77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fekete EM, Zhao Y, Li C, Sabino V, Vale WW, Zorrilla EP. Social defeat stress activates medial amygdala cells that express type 2 corticotropin-releasing factor receptor mRNA. Neuroscience. 2009;162(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forbes NF, Stewart CA, Matthews K, Reid IC. Chronic mild stress and sucrose consumption: validity as a model of depression. Physiol Behav. 1996;60(6):1481–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert P, Allan S, Brough S, Melley S, Miles JN. Relationship of anhedonia and anxiety to social rank, defeat and entrapment. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1–3):141–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halladay LR, Blair HT. Distinct ensembles of medial prefrontal cortex neurons are activated by threatening stimuli that elicit excitation vs. inhibition of movement. J Neurophysiol. 2015;114(2):793–807. doi: 10.1152/jn.00656.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halladay LR, Blair HT. Prefrontal infralimbic cortex mediates competition between excitation and inhibition of body movements during pavlovian fear conditioning. J Neurosci Res. 2016 doi: 10.1002/jnr.23736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harkin A, Houlihan DD, Kelly JP. Reduction in preference for saccharin by repeated unpredictable stress in mice and its prevention by imipramine. J Psychopharmacol. 2002;16(2):115–123. doi: 10.1177/026988110201600201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris RB, Zhou J, Youngblood BD, Smagin GN, Ryan DH. Failure to change exploration or saccharin preference in rats exposed to chronic mild stress. Physiol Behav. 1997;63(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatcher JP, Bell DJ, Reed TJ, Hagan JJ. Chronic mild stress-induced reductions in saccharin intake depend upon feeding status. J Psychopharmacol. 1997;11(4):331–338. doi: 10.1177/026988119701100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog CJ, Czeh B, Corbach S, Wuttke W, Schulte-Herbruggen O, Hellweg R, Flugge G, Fuchs E. Chronic social instability stress in female rats: a potential animal model for female depression. Neuroscience. 2009;159(3):982–992. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134(3483):943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollis F, Duclot F, Gunjan A, Kabbaj M. Individual differences in the effect of social defeat on anhedonia and histone acetylation in the rat hippocampus. Horm Behav. 2011;59(3):331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang GB, Zhao T, Gao XL, Zhang HX, Xu YM, Li H, Lv LX. Effect of chronic social defeat stress on behaviors and dopamine receptor in adult mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;66:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izzo E, Sanna PP, Koob GF. Impairment of dopaminergic system function after chronic treatment with corticotropin-releasing factor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81(4):701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz RJ. Animal model of depression: pharmacological sensitivity of a hedonic deficit. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;16(6):965–968. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koob GF, Heinrichs SC, Pich EM, Menzaghi F, Baldwin H, Miczek K, Britton KT. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in behavioural responses to stress. Ciba Found Symp. 1993;172:277–89. doi: 10.1002/9780470514368.ch14. discussion 290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krishnan V, Han MH, Graham DL, Berton O, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Laplant Q, Graham A, Lutter M, Lagace DC, Ghose S, Reister R, Tannous P, Green TA, Neve RL, Chakravarty S, Kumar A, Eisch AJ, Self DW, Lee FS, Tamminga CA, Cooper DC, Gershenfeld HK, Nestler EJ. Molecular adaptations underlying susceptibility and resistance to social defeat in brain reward regions. Cell. 2007;131(2):391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luking KR, Pagliaccio D, Luby JL, Barch DM. Reward Processing and Risk for Depression Across Development. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(6):456–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundy RF., Jr Gustatory hedonic value: potential function for forebrain control of brainstem taste processing. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008 Oct;32(8):1601–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews K, Forbes N, Reid IC. Sucrose consumption as an hedonic measure following chronic unpredictable mild stress. Physiol Behav. 1995;57(2):241–248. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00286-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meerlo P, Overkamp GJ, Benning MA, Koolhaas JM, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Long-term changes in open field behaviour following a single social defeat in rats can be reversed by sleep deprivation. Physiol Behav. 1996;60(1):115–119. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miczek KA. A new test for aggression in rats without aversive stimulation: differential effects of d-amphetamine and cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1979;60(3):253–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00426664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miczek KA, Yap JJ, Covington HE., 3rd Social stress, therapeutics and drug abuse: preclinical models of escalated and depressed intake. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;120(2):102–128. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montagud-Romero S, Reguilon MD, Roger-Sanchez C, Pascual M, Aguilar MA, Guerri C, Minarro J, Rodriguez-Arias M. Role of dopamine neurotransmission in the long-term effects of repeated social defeat on the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;71:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muscat R, Willner P. Effects of dopamine receptor antagonists on sucrose consumption and preference. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;99(1):98–102. doi: 10.1007/BF00634461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muscat R, Willner P. Suppression of sucrose drinking by chronic mild unpredictable stress: a methodological analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16(4):507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papp M, Muscat R, Willner P. Subsensitivity to rewarding and locomotor stimulant effects of a dopamine agonist following chronic mild stress. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;110(1–2):152–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02246965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papp M, Willner P, Muscat R. An animal model of anhedonia: attenuation of sucrose consumption and place preference conditioning by chronic unpredictable mild stress. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;104(2):255–259. doi: 10.1007/BF02244188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paterson NE, Markou A. Animal models and treatments for addiction and depression co-morbidity. Neurotox Res. 2007;11(1):1–32. doi: 10.1007/BF03033479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porcelli AJ, Lewis AH, Delgado MR. Acute stress influences neural circuits of reward processing. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:157. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riga D, Theijs JT, De Vries TJ, Smit AB, Spijker S. Social defeat-induced anhedonia: effects on operant sucrose-seeking behavior. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:195. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rygula R, Abumaria N, Flugge G, Fuchs E, Ruther E, Havemann-Reinecke U. Anhedonia and motivational deficits in rats: impact of chronic social stress. Behav Brain Res. 2005;162(1):127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scholtens J, Van de Poll NE. Behavioral consequences of agonistic experiences in the male S3 (Tryon maze dull) rat. Aggress Behav. 1987;13:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuster R, Berger BD, Swanson HH. Cooperative social coordination and aggression: II. Effects of sex and housing among three strains of intact laboratory rats differing in aggressiveness. Q J Exp Psychol B. 1993;46(4):367–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spierling SR, Kreisler AD, Zorrilla EP. Intermittent access to palatable food leads to compulsive self-administration and hyperirritability during withdrawal in rats. The Society for the Study of Ingestive Behavior Annual Meeting; Porto, Portugal. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stafford D, LeSage MG, Glowa JR. Progressive-ratio schedules of drug delivery in the analysis of drug self-administration: a review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;139(3):169–84. doi: 10.1007/s002130050702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamashiro KL, Hegeman MA, Nguyen MM, Melhorn SJ, Ma LY, Woods SC, Sakai RR. Dynamic body weight and body composition changes in response to subordination stress. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(4):440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telzer EH. Dopaminergic reward sensitivity can promote adolescent health: A new perspective on the mechanism of ventral striatum activation. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2016;17:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Galvan A. Neural sensitivity to eudaimonic and hedonic rewards differentially predict adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(18):6600–6605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323014111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tornatzky W, Miczek KA. Long-term impairment of autonomic circadian rhythms after brief intermittent social stress. Physiol Behav. 1993;53(5):983–993. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90278-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaccarino FJ, Amalric M, Swerdlow NR, Koob GF. Blockade of amphetamine but not opiate-induced locomotion following antagonism of dopamine function in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24(1):61–65. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valenstein ES, Cox VC, Kakolewski JW. Polydipsia elicited by the synergistic action of a saccharin and glucose solution. Science. 1967;157(3788):552–554. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3788.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Dijken HH, Mos J, van der Heyden JA, Tilders FJ. Characterization of stress-induced long-term behavioural changes in rats: evidence in favor of anxiety. Physiol Behav. 1992;52(5):945–951. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90375-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vianna DM, Borelli KG, Ferreira-Netto C, Macedo CE, Brandao ML. Fos-like immunoreactive neurons following electrical stimulation of the dorsal periaqueductal gray at freezing and escape thresholds. Brain Res Bull. 2003;62(3):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Volpicelli JR, Ulm RR, Hopson N. The bidirectional effects of shock on alcohol preference in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1990;14(6):913–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb01837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Von Frijtag JC, Reijmers LG, Van der Harst JE, Leus IE, Van den Bos R, Spruijt BM. Defeat followed by individual housing results in long-term impaired reward- and cognition-related behaviours in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2000;117(1–2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watt MJ, Roberts CL, Scholl JL, Meyer DL, Miiller LC, Barr JL, Novick AM, Renner KJ, Forster GL. Decreased prefrontal cortex dopamine activity following adolescent social defeat in male rats: role of dopamine D2 receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231(8):1627–1636. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3353-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willner P, Towell A, Sampson D, Sophokleous S, Muscat R. Reduction of sucrose preference by chronic unpredictable mild stress, and its restoration by a tricyclic antidepressant. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;93(3):358–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00187257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wojnicki FH, Babbs RK, Corwin RL. Reinforcing efficacy of fat, as assessed by progressive ratio responding, depends upon availability not amount consumed. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(4):316–21. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zacharko RM, Bowers WJ, Kokkinidis L, Anisman H. Region-specific reductions of intracranial self-stimulation after uncontrollable stress: possible effects on reward processes. Behav Brain Res. 1983;9(2):129–141. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(83)90123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang S, Paul J, Nantha-Aree M, Buckley N, Shahzad U, Cheng J, DeBeer J, Winemaker M, Wismer D, Punthakee D, Avram V, Thabane L. Empirical comparison of four baseline covariate adjustment methods in analysis of continuous outcomes in randomized controlled trials. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:227–235. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S56554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.