Abstract

Purpose:

To develop a fast 2D method for MRI near metal with reduced B0 in-plane and through-slice artifacts.

Methods:

Recent Multi-spectral imaging (MSI) approaches reduce artifacts in MR images near metal, but require 3D imaging of multiple excited volumes regardless of imaging geometry or artifact severity. The proposed 2D MSI method rapidly excites a limited slice and spectral region using gradient reversal between excitation and refocusing pulses, then uses standard 2D imaging, with the process repeating to cover multiple spectral offsets that are combined as in other MSI techniques. 2D MSI was implemented in a spin-echo-train sequence and validated in phantoms and in vivo by comparing it with standard spin-echo imaging and existing MSI techniques.

Results:

2D MSI images for each spatial-spectral region follow isocontours of the dipole-like B0 field variation, and thus frequency variation, near metal devices. Artifact correction in phantoms and human subjects with metal is comparable to 3D MSI methods, and superior to standard spin-echo techniques. Scan times are reduced compared with 3D MSI methods in cases where a limited number of slices is needed, though signal-to-noise ratio is also reduced as expected.

Conclusion:

2D MSI offers a fast and flexible alternative to 3D MSI for artifact reduction near metal.

Keywords: Metal, Artifact, Multi-spectral Imaging, SEMAC, MAVRIC

Introduction

Numerous medical conditions are treated very successfully using implanted metal devices, including dental fillings, spinal fixations, stabilization hardware and total joint replacements. Although many of these devices do not pose a safety risk in MRI, magnetic susceptibility differences between metal and tissue cause a variation of the static magnetic field [1], causing artifacts that include signal loss, geometric distortion, and hyperintense “pile-up” artifacts [2]. The severity of such artifacts depends on the the size, shape and composition of the metal device, its orientation in the magnetic field, the strength of the magnetic field, and numerous imaging parameters [3].

Multi-spectral imaging (MSI) approaches such as SEMAC (slice encoding for metal artifact correction), MAVRIC (multi-acquisition variable-resonance image combination), MAVRIC-SL (selective MAVRIC) and others have shown promise for artifact-reduced imaging near metal [4–7]. These methods all excite multiple “bins” (frequency bands in MAVRIC, or distorted slices in SEMAC or MAVRIC-SL) whereby frequency-encode distortion is limited by the range of resonances excited in each bin, and phase-encoding in the other two directions avoids distortion. In general the 3D imaging of these methods is slow and inflexible, in spite of the use of partial Fourier, parallel imaging and compressed sensing [8–10] to reduce encoding times. Alternatively, reduced-excitation-region approaches using varied excitation/refocusing pulse bandwidths in combination with SEMAC or MAVRIC can reduce scan times by reducing the encoded field-of-view (FOV) [11]. Although scan times are long, promising applications of 3D MSI methods have been demonstrated for post-operative imaging of the hip [12,13], spine [14], and knee [15], or near dental implants [16].

Here we investigate 2D MSI, a fast, reduced-artifact 2D imaging alternative that offers considerable flexibility when the number of slices is limited (e.g. for localization), or when off-resonance variation is small (near smaller devices or metals with relatively small susceptibility variations). 2D MSI limits the spatial extent of each excited volume to the slice of interest, while also limiting the spectral extent to limit readout distortion, and can equivalently be considered a 2D version of the original MAVRIC or SEMAC approaches, adding slice-selectivity or frequency-selectivity respectively.

Methods

The excitation and imaging regions for both purely-spectral and spatially-selective approaches to MSI, along with the proposed 2D MSI method, are shown in Fig. 1. The presence of metal results in large and complex variations in the magnetic field that would cause severe spatial distortions in standard slice-selective imaging [3]. The existing MSI methods use 3D encoding to resolve the shape of excited regions resulting in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) benefits, but increased scan times. While selective methods may reduce the extent of the encoded FOV [5,6], these methods remain inflexible when a small volume of interest is required, since additional slices (olor and red in Fig. 1 must be excited away from the metal to include regions with larger frequency offsets. Inspired by efforts to limit the excited (and thus encoded) volumes in MSI methods [11] we demonstrate the 2D MSI method [17], which aims to completely avoid the need for 3D encoding, as suggested in ref. [18].

Figure 1:

Excited regions and imaging strategies with purely-spectral MAVRIC (a), selective approaches such as SEMAC or MAVRIC-SL (b), and the proposed 2D MSI (c). Existing methods excite frequency bands (a) or slice/slab regions in the presence of a gradient (b), and use 3D encoding to resolve the image. 2D MSI aims to excite a finite spatial and spectral extent so that only 2D encoding is necessary, to reduce the time needed when the volume is limited. [1.5 column]

All images were acquired on a 3.0T GE Discovery MR750 system with gradients capable of 50 mT/m maximum amplitude and 200 mT/m/ms slew rates. Receive coils varied by experiment as described below. All human subjects signed informed consent as approved by our institution’s investigational review board (IRB).

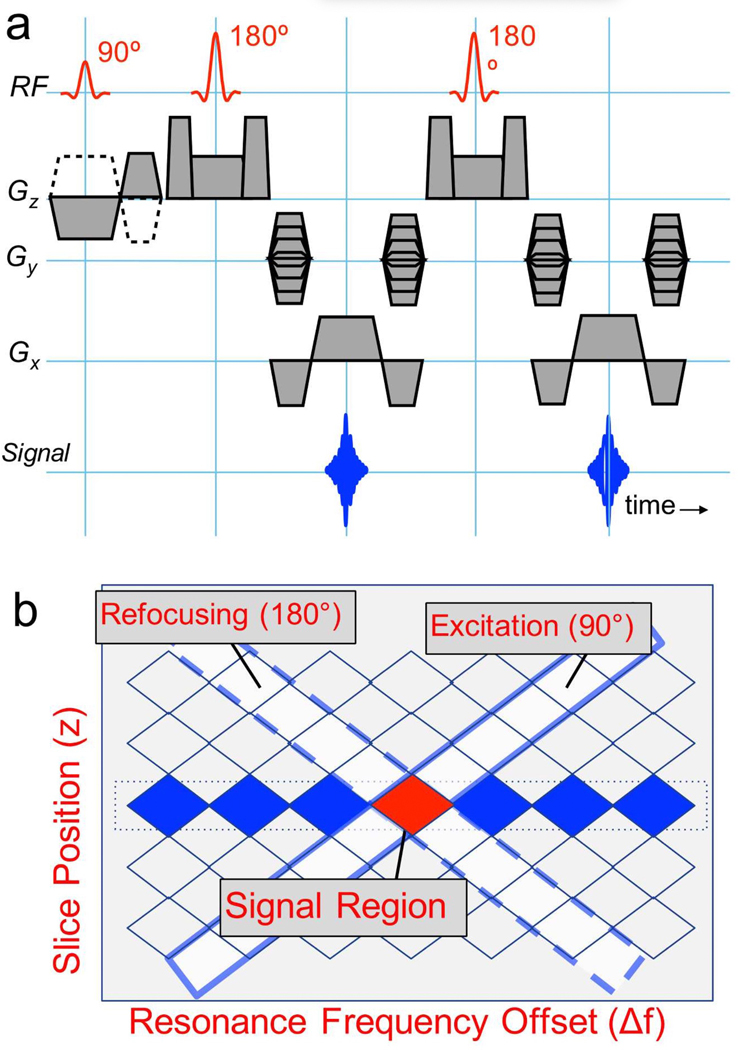

To selectively excite both a limited slice and limited (but large) bandwidth, we used a simple gradient-reversal technique (Fig. 2). The slice-selection gradient polarity was inverted during the excitation RF with respect to that of all refocusing RF pulses, so that only spins experiencing both excitation and refocusing produce signal. This approach has been used previously for fat suppression [19], and to suppress off-resonance signal near metal to increase needle conspicuity and/or to reduce artifacts [20,21]. For the ith slice at location zi and jth resonance offset (Δfj), excitation and refocusing pulse modulation frequencies fi,j and respectively are calculated simply as fi,j = γ/2πGzzi + Δfj and where Gz is the selection gradient amplitude for excitation and γ is the gyromagnetic ratio. The receive frequency can be set to Δfj for fast image combination. However, it could be preferable to use no receive frequency offset so that spins are aligned regardless of Δfj, and then use a deblurring approach during image combination based on a field-map extracted from the data itself.

Figure 2:

(a) The 2D MSI pulse sequence is a standard 2D spin-echo-train sequence, but the selection and refocusing gradients for the excitation (90°) pulse are negated. In practice, slice-refocusing gradients are typically combined with crusher pulses, and the refocusing RF pulse flip angles are usually reduced from 180°, and modulated over the echo train. (b) Gradient reversal between excitation and refocusing RF pulses results in an “inner-volume” excitation in frequency-slice space (on-resonance band at center slice position is highlighted in red). For a given slice location on-resonance, the modulation frequency for excitation (fi,j) and refocusing () pulses has opposite sign, since the gradients are opposite. Additional frequency bands centered at frequencies Δfj are excited by adding Δfj (equal sign) to excitation and refocusing pulse frequencies to include all frequencies at a given slice location (blue regions). [1 column wide]

With the exception of phantom validation (see below), we used a single-shot fast-spin-echo (FSE) pulse sequence with variable refocusing angles. (We chose to use single-shot 2DMSI because it is unlikely to replace MAVRIC-SL, but rather offer a fast localizer or fast add-on scan for applications where fewer slices are needed or where the distortion is lower.) The RF pulses for excitation and refocusing were identical, but scaled for different flip angles, and were 480 μs sinc-like Shinnar-Le Roux pulses with approximately 1.2 kHz bandwidth at half-maximum, aimed at minimizing echo spacing. Frequency bands (Δfj) were spaced 900 Hz apart, and scanned in an odd-then-even order to reduce saturation effects between adjacent bins. Acquisitions used high receive bandwidth of ±125 kHz (651 Hz/pixel), to limit in-plane distortion to within about ±0.7 pixels, and half-Fourier phase encoding to reduce echo-train blurring compared with center-out phase encoding. Acquired data were demodulated during acquisition by the frequencies Δfj. By default, data from different frequency bins were combined using a root-mean-square (RMS) approach or complex sum as specified, with the RMS generally improving SNR at a cost of minor shading.

To evaluate the artifact correction abilities of different sequences, we imaged an agar phantom (at isocenter) with a titanium shaft / cobalt-chromium head shoulder replacement. In order to match parameters as closely as possible, 2D MSI was compared with both SEMAC and 2D FSE by directly modifying the SEMAC sequence by (1) flipping the excitation gradient and (2) turning off slice phase encoding and VAT gradients as appropriate. The SEMAC scan excited 24 slices and encoded each with 24 z phase encodes in 9:22 minutes (25% speedup using elliptical k-space sampling). The 2D MSI scan excited 24 interleaved frequency bins for slice, then repeated this for all 24 slices for scan times of 0:32 min per slice, and 12:48 min total. FSE used the identical sequence as 2D MSI with 24 interleaved slices, but with a single frequency bin and without gradient reversal, for 0:32 min total scan time. For all sequences, we imaged at 3T with TR/TE=3000/12 ms, 2mm-thick slices, 384×120 matrix over 24×18cm FOV, with ±125 kHz receive bandwidth (651 Hz/pixel), 1.2 kHz RF bandwidth, echo-train-length (ETL) of 8, and no parallel imaging. Note that the purpose of this comparison was not to achieve faster imaging, but rather to compare artifact reduction.

To illustrate the 2D MSI method in vivo, we scanned the knee of a subject who had titanium screws used for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, using a standard 8-channel transmit/receive knee coil. This is an example of an application where the metal artifact is small, and may not justify longer scans. Coronal single-shot FSE with a 744 ms scan time per slice was compared with coronal 2D MSI using interleaved single-shot FSE acquisitions for each of 19 frequency bins spaced 800 Hz apart, with modulated refocusing angles to enable a 548 ms repetition time, and total scan time of 10 s per slice. Other scan parameters were a TE of 36 ms, 18×18 cm2 FOV, 384×256 matrix, 488 Hz/pixel readout bandwidth, and 4 mm slice thickness. The 2D MSI reconstruction was performed using a simple sum-of-squares bin combination, then repeated using the center-of-mass field map and deblurring procedure described in ref. [6].

We compared the same 2D MSI method as described for the knee experiment to single-shot FSE and MAVRIC-SL in a subject with spinal hardware including stainless steel pedicle screws, using a standard 12-channel spine coil (GE Healthcare). All scans used a 26×18 cm2 FOV with 384×256 in-plane matrix, sagittal scan plane, and a readout bandwidth of 488 Hz/pixel. 2D MSI and single-shot FSE acquired 10 slices, each 5 mm thick for total scan times of 1:56 and 0:22 respectively. 2D MSI images were acquired sequentially with 16 frequency bins, in 12 seconds/slice. MAVRIC-SL used a 4 mm slice thickness with 22 spectral bins and an echo-train-length of 24 for a scan time of 7:16. Images were compared qualitatively for their ability to discern nerve roots, and for size of artifact.

Results

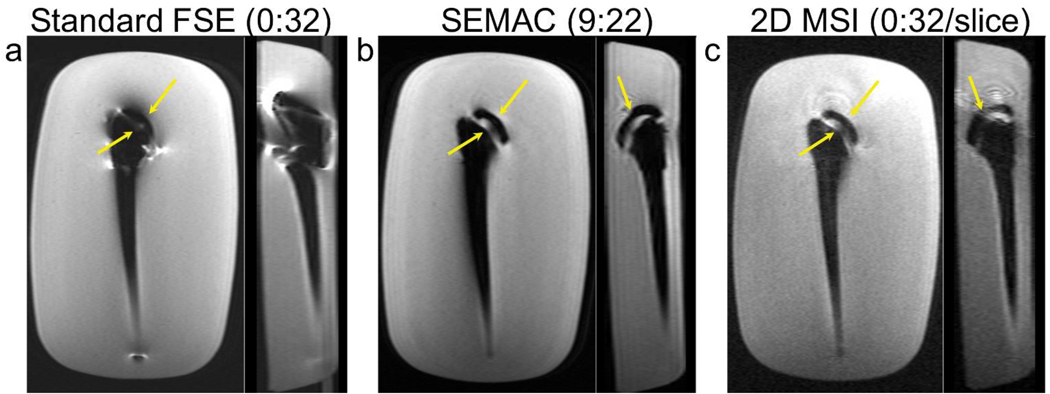

Images from the FSE, SEMAC and 2D MSI acquisitions in a phantom with a total shoulder replacement are shown in Fig. 3. The in-plane image, corresponding to a coronal view for the clinical usage of this device, and the orthogonal “sagittal” view are shown for each sequence. In-plane and through-slice distortion artifacts near metal are substantially reduced by both the SEMAC and 2D MSI sequences (arrows in Fig. 3). Comparing SEMAC to 2D MSI, the depiction of the implant head and neck regions are quite similar, indicating similar artifact correction. SEMAC images have higher SNR, since slice-phase-encoding leads to additional averaging like any 3D acquisition compared with 2D, and also have less “ripple” artifact. The ripple artifact is likely due to the diamond-shaped profiles (Fig. 2b) of slices in 2D MSI, meaning the sequence is sensitive to the amount of frequency overlap of adjacent excited frequency bands.

Figure 3:

Comparison of FSE (a), SEMAC (b) and 2D MSI (c) images in a total-shoulder-replacement phantom. The acquired plane, corresponding to coronal when the device is oriented in a patient (left), and a “sagittal” reformat (right) are shown for each scan. FSE images show severe distortion artifacts near the device. These are substantially reduced, both in-plane and through-slice in both SEMAC and 2D MSI, with similar depiction of the device structure between the latter methods. SEMAC images have higher SNR than 2D MSI due to averaging, and reduced ripple. [1.5 columns wide]

Images from the knee of a subject with titanium screws used for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction are shown in Fig. 4. Images from individual frequency bands, spaced 800 Hz apart, show the decomposition of the spatial and spectral information by 2D MSI, and the deblurring reconstruction [6] improves sharpness in the readout direction. The 2D MSI image avoids some through-slice distortion evident in FSE, which would probably otherwise not be identified as such.

Figure 4:

Demonstration of 2D MSI component images in a subject with titanium screw in his knee. (a) Images acquired for frequency offsets of −2 to 2 kHz. (b) Field map obtained using a center-of-mass combination of component images. (c) Single-shot 2D fast spin echo (d) Single-shot 2D MSI images without deblurring and (e) Single-shot 2D MSI images with deblurring, showing sharper resolution in the frequency-encode (S/I) direction (solid arrows). Note that there is some minor through-slice artifactual signal (dotted arrows) and signal loss (dashed arrow) in (c) that is avoided in (d) and (e). [1.5 columns wide]

Figure 5 shows single-shot FSE (SSFSE), 2D MSI and MAVRIC-SL images in a subject with spinal hardware. The signal void size is slightly larger in 2D MSI than MAVRIC-SL, but smaller than that of SSFSE. Through-slice distortions in SSFSE obscure nerve roots that are visible in both 2D MSI and MAVRIC-SL. In this example, 2D MSI offers a 72% scan-time reduction compared with MAVRIC-SL, since a smaller number of slices can be excited and imaged while covering the full width of the spine. In MAVRIC-SL (or SEMAC) acquisitions, a wider range of slice coverage is necessary in order to excite signal near the metal. Note that the use of modulated flip angles in 2D MSI reduces blurring due to T2 decay over the echo train, which would otherwise be much worse than that of MAVRIC-SL.

Figure 5:

Comparison of SSFSE (a), 2D MSI (b) and MAVRIC-SL (c) in a subject with spinal fixation hardware includig pedicle screws. The L5 nerve root and surrounding area is obscured in standard SSFSE images by signal loss (solid white arrow) and through-slice distortion (dotted white arrow), but comparably visible in 2D MSI and MAVRIC-SL (yellow arrows). [1.5 columns wide]

Discussion

2D MSI uses a simple gradient reversal between slice-selection and refocusing pulses in a spin-echo train to offer rapid inner-volume excitation of spatially and spectrally selective regions. Multiple spectral regions are excited and imaged to build up the information in a slice, with minimal readout distortion in each region because of the limited frequency range. We have demonstrated the artifact correction capability compared with 3D MSI (SEMAC), shown how the spectral regions are used to build up slice content in a knee example, and demonstrated faster scanning for spinal imaging near metal. Further applications and considerations for 2D MSI are described below. While these examples are typical of our experience, given the different types, shapes and sizes of metal devices, and different needs of applications, 2DMSI will require more testing in a clinical setting to tune it for routine use in different applications.

The relative scanning efficiencies of 2D MSI and 3D selective MSI techniques depend on the application - primarily the range of resonance offsets and the spatial range of desired slices. Although prior work has shown that areas of extreme frequency gradients or very large frequency offsets may be not recoverable due to additional effects [22,23], we will ignore these effects for simplicity in this discussion. Assuming an excitation bandwidth (or increment) B, number of slices of interest N, and frequency range ±Δf, 2D MSI would require 2Δf/B times as many excitations as standard spin-echo imaging, regardless of the number of slices of interest. SEMAC would require 2Δf/B z-direction phase encodings, as well as 2Δf/B extra slices in the worst case, for a scan increase over spin echo of a factor of

| (1) |

The second term in parentheses is the key difference - to excite frequency offsets in a central slice requires excitation of additional outer slices in SEMAC, as well as z-direction phase-encoding for these outer slices. Thus when N is small, the advantages of 2D MSI are more clear. Another point is that a minimum number of z-direction phase encodes is needed for Fourier encoding, so this may further reduce efficiency of 3D selective MSI methods. Similar to the MAVRIC technique, another advantage of 2D MSI is that a limited spectral coverage can be directly prescribed without artifacts (aside from signal voids) as could be seen in Fig. 4a where for example only 3 spectral bins could be included. However, as mentioned above, the SNR benefit of averaging in 3D methods is a considerable advantage compared with 2D MSI.

While this work describes a simple implementation of 2D MSI, some additional limitations should be considered. First, the SNR is lower than in 3D MSI due to less averaging, which may limit the usable image resolution. In some cases, the background frequency gradients can partially cancel the crusher gradients leading to excitation of additional out-of-slice signal that can increase distortion artifacts. The gradient reversal increases sensitivity to gradient timing or delays as well as eddy currents, which could manifest as a loss of CPMG. However, carefully tuning delays was sufficient to avoid non-CPMG effects due to timing errors. Further experimentation using phase-cycling for CPMG could be useful to better understand this effect. Gradient non-linearity might cause the same slice shift and distortion effects away from isocenter as in standard spin-echo methods, and may also stretch the diamond shape of excited regions due to different gradient slope.

2D MSI can be implemented as an interleaved multi-shot or single-shot spin-echo sequence. In cases of multi-shot imaging, the excitation order would be important to minimize saturation between bands. To avoid saturation in mulit-slice imaging, the excitation order could interleave slices in the innermost loop, just as in standard multi-shot 2D imaging. In our single-shot FSE method, we interleaved odd then even frequencies, which was sufficient even when the slice loop was the outer loop.

The 2D MSI excitation characteristics could be further explored in greater detail. The profile used here is diamond-shaped in the f-z plane (Fig. 2b). The requirements of this profile are high spectral bandwidth in order to cover the full spectrum in a low number of excitations, and time-efficient excitation. Although standard spectral-spatial pulses [24] could achieve more accurate profiles, the bandwidth is limited and time efficiency is lower. The gradient-reversal technique shown is very fast, but results in a rough profile, and spectral tails that could degrade image quality. Additionally, the increased ripple artifact in 2D MSI (Fig. 3) may be evidence that the diamond-shaped profiles (Fig. 2b) result in sensitivity to the amount of frequency overlap between adjacent excited frequency bands. Instead, the slice (or refocusing) gradient could be turned off completely, leading to a parallelogram-shaped region which may have advantages for frequency selectivity, but other limitations. Complete investigation of pulse profiles remains as future work. This investigation could include more thorough experiments regarding ripple artifacts, which result from the spatial off-resonance variation and the spectral profiles, but manifest differently to those of SEMAC or MAVRIC as previously investigated [25].

A simple application of 2D MSI is as a scout scan for MRI near metal. Because frequency components are scanned sequentially, one option is to scan outward from 0 Hz offset until no more signal is observed, then repeat this process in the other direction, as can be seen in Fig. 4a. This obtains the distribution of frequencies in an excited slice region, in addition to a usable 2D MSI image. It should be noted that there are alternatives to obtain the frequency distribution, such as using low-resolution MAVRIC [26], or turning off the readout gradient in SEMAC or other selective approaches [27,28], which may be better suited depending on the application.

Conclusion

2D multi-spectral imaging (MSI) offers a more flexible approach than 3D MSI methods, which can reduce scan times for many applications, while offering comparable correction of artifacts due to B0 variations near metal. 2D MSI may be attractive as a localizer scout that offers both spectral information and diagnostic combined images.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants: R21-EB019723, R01-EB017739, P41-EB015891 and GE Healthcare

References

- [1].Schenck JF. The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Med Phys 1996; 23:815–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ladd ME, Erhart P, Debatin JF, Romanowski BJ, Boesiger P, McKinnon GC. Biopsy needle susceptibility artifacts. ”Magn Reson Med.” 1996; 36:646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Koch K, Hargreaves B, Pauly K, Chen W, Gold G, King K. Magnetic resonance imaging near metal implants. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2010; 32:773–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Koch KM, Lorbiecki JE, Hinks RS, King KF. A multispectral three-dimensional acquisition technique for imaging near metal implants. Magn Reson Med 2009; 61:381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lu W, Pauly KB, Gold GE, Pauly JM, Hargreaves BA. SEMAC: Slice encoding for metal artifact correction in MRI. Magn Reson Med 2009; 62:66–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Koch K, Brau A, Chen W, Gold G, Hargreaves B, Koff M, McKinnon G, Potter H, King K. Imaging near metal with a MAVRIC-SEMAC hybrid. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2011; 65:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Li G, Nittka M, Paul D, Lauer L. MSVAT-SPACE for fast metal implants imaging. In: Proceedings 19th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Montreal, Montreal, 2011. p. 3171. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hargreaves B, Chen W, Lu W, Alley M, Gold G, Brau A, Pauly J, Pauly K. Accelerated slice encoding for metal artifact correction. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2010; 31:987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Worters P, Sung K, Stevens K, Koch K, Hargreaves B. Compressed-sensing multispectral imaging of the postoperative spine. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2013; 37:243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Otazo R, Nittka M, Bruno M, Raithel E, Geppert C, Gyftopoulos S, Recht M, Rybak L. Sparse-semac: rapid and improved semac metal implant imaging using sparse-sense acceleration. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2016;. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].den Harder CJM, van Yperen GH, Blume UA, Bos C. Off-resonance suppression for multispectral MR imaging near metallic implants. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2015; 73:233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hayter C, Koff M, Shah P, Koch K, Miller T, Potter H. MRI after arthroplasty: comparison of MAVRIC and conventional fast spin-echo techniques. American Journal of Roentgenology 2011; 197:W405–W411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nawabi DH, Gold S, Lyman S, Fields K, Padgett DE, Potter HG. MRI predicts ALVAL and tissue damage in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res 2014; 472:471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee YH, Lim D, Kim E, Kim S, Song HT, Suh JS. Usefulness of slice encoding for metal artifact correction (SEMAC) for reducing metallic artifacts in 3-T MRI. Magn Reson Imaging 2013; 31:703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sutter R, Ulbrich E, Jellus V, Nittka M, Pfirrmann C. Reduction of metal artifacts in patients with total hip arthroplasty with slice-encoding metal artifact correction and view-angle tilting MR imaging. Radiology 2012; 265:204–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gunzinger JM, Delso G, Boss A, Porto M, Davison H, von Schulthess GK, Huellner M, Stolzmann P, VeitHaibach P, Burger IA. Metal artifact reduction in patients with dental implants using multispectral three-dimensional data acquisition for hybrid PET/MRI. EJNMMI physics 2014; 1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hargreaves BA, Taviani V, Yoon D. Fast 2D imaging for distortion correction near metal implants. In: Proceedings 22nd Scientific Meeting of the ISMRM, Milan 2014, Milan, 2014. p. 615. [Google Scholar]

- [18].den Harder CJM, Bos C, Blume UA. Restriction of the imaging region for MRI in an inhomogeneous magnetic field, September 2012, European Patent App. EP2500742A1. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Park H, Kim D, Cho Z. Gradient reversal technique and its applications to chemical-shift-related NMR imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine 1987; 4:526–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Butts K, Pauly JM, Daniel BL, Kee S, Norbash AM. Management of biopsy needle artifacts: Techniques for RF-refocused MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 9:586–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bos C, den Harder CJ, van Yperen G. MR imaging near orthopedic implants with artifact reduction using view-angle tilting and off-resonance suppression. In: Proceedings 18th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Stockholm, Stockholm, 2010. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Koch KM, King KF, Carl M, Hargreaves BA. Imaging near metal: the impact of extreme static local field gradients on frequency encoding processes. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2014; 71:2024–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Smith MR, Artz NS, Wiens C, Hernando D, Reeder SB. Characterizing the limits of MRI near metallic prostheses. ”Magn Reson Med.” 2015; 74:1564–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Meyer C, Pauly J, Macovski A, Nishimura D. Simultaneous spatial and spectral selective excitation. Magn Reson Med 1990; 15:287–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].den Harder CJM, van Yperen GH, Blume UA, Bos C. Ripple artifact reduction using slice overlap in slice encoding for metal artifact correction. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2015; 73:318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kaushik SS, Marszalkowski C, Koch KM. External calibration of the spectral coverage for three-dimensional multispectral MRI. Magn Reson Med 2016; 76:1494–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hargreaves B, Gold G, Pauly J, Pauly K. Adaptive slice encoding for metal artifact correction. In: Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, Stockholm, 2010. p. 3083. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li G, Nittka M, Paul D, Zhang W. Distortion scout in metal implants imaging. In: Proceedings 19th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Montreal, Montreal, 2011. p. 3169. [Google Scholar]