Key Points

Question

Do copayments reduce the use of home health care among older adults?

Findings

In this case-control study of 36 Medicare Advantage plans, increased copayments for home health care were not associated with changes in the proportion of enrollees receiving home health care, the number of home health episodes per user, or home health days per user.

Meaning

We found no evidence that imposing copayments meaningfully reduces the use of home health care, but such cost sharing may add substantially to the burden of out-of-pocket spending among frail older adults.

This case-control study examines the association of home health copayments with use of home health service among Medicare Advantage enrollees.

Abstract

Importance

Several policy proposals advocate introducing copayments for home health care in the Medicare program. To our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed this cost-containment strategy.

Objective

To determine the association of home health copayments with use of home health services.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A difference-in-differences case-control study of 18 Medicare Advantage (MA) plans that introduced copayments for home health care between 2007 and 2011 and 18 concurrent control MA plans. The study included 135 302 enrollees in plans that introduced copayment and 155 892 enrollees in matched control plans.

Exposures

Introduction of copayments for home health care between 2007 and 2011.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Proportion of enrollees receiving home health care, annual numbers of home health episodes, and days receiving home health care.

Results

Copayments for home health visits ranged from $5 to $20 per visit, which were estimated to be associated with $165 (interquartile range [IQR], $45-$180) to $660 (IQR, $180-$720) in out-of-pocket spending for the average user of home health care. The increased copayment for home health care was not associated with the proportion of enrollees receiving home health care (adjusted difference-in-differences, −0.15 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.38 to 0.09), the number of home health episodes per user (adjusted difference-in-differences, 0.01; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.03), and home health days per user (adjusted difference-in-differences, −0.19; 95% CI, −3.02 to 2.64). In both intervention and control plans and across all levels of copayments, we observed higher disenrollment rates among enrollees with greater baseline use of home health care.

Conclusions and Relevance

We found no evidence that imposing copayments reduced the use of home health services among older adults. More intensive use of home health services was associated with increased rates of disenrollment in MA plans. The findings raise questions about the potential effectiveness of this cost-containment strategy.

Introduction

From 2000 to 2010, Medicare home health care expenditures increased from $8 billion to $19 billion, making home health care one of the fastest growing components of Medicare spending. Under traditional Medicare’s benefit design, home health care is provided at no cost to the patient, which means there is no financial incentive for beneficiaries to restrict their use of these services. To address this concern the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission and the Bowles-Simpson deficit reduction committee have expressed support for the imposition of a copayment for the use of home health care. President Obama’s 2017 budget proposal called for a home health copayment of $100 per episode beginning in 2020 and estimated that this measure would save $1.3 billion over 10 years. Proposed legislation in the US House of Representatives also includes a $100 copayment for each home health episode. Despite this momentum, there is no empirical evidence to guide policymakers about the impact of home health cost sharing in the Medicare program.

Although older adults may be particularly responsive to small changes in outpatient cost sharing, the effects of copayments for home health care may be distinct from those observed for other health services. To receive home health services, the traditional Medicare program requires that patients be homebound. Furthermore, Medicare policy requires physicians to assess and certify patients’ need for home health care during a face-to-face encounter, and home health agencies must submit documentation of this certification for Medicare billing. Patients’ needs for home health care must be recertified every 60 days. These factors suggest that the use and intensity of home health care may be primarily driven by physician decisions rather than patients’ demand. Therefore, increasing home health out-of-pocket costs may not necessarily reduce utilization, especially for frail homebound patients.

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans provide an opportunity to investigate the consequences of home health copayments. Unlike traditional Medicare, these plans have the flexibility to introduce patient cost sharing for this service, in addition to applying other cost-containment strategies, such as prior authorization, utilization review, and restricting its network to more efficient providers. Using a quasiexperimental design, we sought to determine the association between introducing home health copayments and the use of home health services. In addition, given that beneficiaries who receive home health services may opt to leave their plan to avoid copayments, we also assessed rates of disenrollment among MA enrollees who did and did not receive home health services in the year prior to the copayment increase.

Methods

Data Sources

We merged the 2007 to 2011 Medicare Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) with the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), which provides data on the use of home health services. All Medicare-certified home health care providers are required to submit OASIS assessments for all patients (irrespective of insurance) at the start of care, at 60 days, and at discharge. We also acquired information on MA plans’ benefits for Medicare-covered services, including the required copayment for each home health visit and summary data on the average expected monthly out-of-pocket costs (including premiums and cost sharing) in each MA plan. Finally, to estimate potential out-of-pocket spending associated with a given home health copayment level, we merged OASIS data with Medicare home health claims for traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Brown University’s Human Research Protections Office and the CMS Privacy Board approved the study protocol.

Selection of Case and Control MA Plans

The proportion of plans with home health copayments decreased from 21.8% to 12.6% from 2007 to 2011. Because we aimed to examine how plan members responded to new home health copayments, we identified 18 MA plans that introduced copayments for home health visits in any year between 2007 and 2011, hereafter referred to as “case plans.” We matched these 18 case plans to 18 concurrent control MA plans that maintained no cost sharing for home health visits over the same time period in which case plans introduced copayments. For each case plan, we selected control plans in the same region and with similar expected average monthly out-of-pocket payments for medical services throughout the study period. Then we created a propensity score based on plan size and enrollees’ demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, ZIP code–level income) and used one-to-one matching for case and control plans on the basis of nearest match in propensity scores.

Study Population

Our main study cohort included beneficiaries who were enrolled in a study MA plan in the year prior to the introduction of home health copayments. Any beneficiaries who joined the plan after the introduction of copayments were excluded. We also excluded Medicare beneficiaries younger than 65 years of age and those dually-eligible for full Medicaid coverage because Medicaid covers Medicare’s cost sharing. The study included 135 302 enrollees in MA plans that introduced copayments for home health care between 2007 and 2011 and 155 892 enrollees from concurrent control MA plans. Among this population, 10 417 enrollees in case plans and 11 629 in control plans used home health care in the year before the copayment was introduced.

Variables

The main outcome variables for each MA member were: (1) the number of annual home health episodes, (2) the annual duration of home health care (in days), and (3) use of any home health care services. The first 2 outcome variables were restricted to those who used home health care. We only considered utilization that occurred while the member was enrolled in his or her plan. For members that disenrolled in the year when the copayment was introduced, our utilization measure only counted these members’ home health utilization prior to the copayment increase. We measured the share of beneficiaries who disenrolled as an additional outcome.

The number of home health episodes was determined based on admission assessments in OASIS. Days covered by home health care were defined as the duration between the admission date and discharge date for each episode. For persons with concurrent episodes from distinct providers, we summed home health episodes and days.

For our primary utilization analyses, the independent variables were indicator variables for whether the plan was a case plan, whether the episode took place after the copayment introduction, and an interaction of these 2 variables. Covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity (black, white, Hispanic, Asian, or other), and ZIP code–level income derived from national Census data.

Utilization Analyses

We used a difference-in-differences approach by subtracting the change in utilization in control plans from the concurrent change in plans that increased cost sharing. To test the parallel-trends assumption, we evaluated home health utilization in the 2 years prior to the copayment introduction. This analysis was conducted for 11 case plans that had no copayments for 2 years prior to home health copayment increase and submitted valid HEDIS data in each of these 2 years, and each of these plans’ matched control plan. These analyses suggested parallel trends for the proportion of enrollees receiving home health care or the annual number of home health episodes per user. For home health days per user, we observed a modest decline in utilization in case plans relative to controls prior to the copayment (adjusted difference-in-differences, −4.92; 95% CI, −8.27 to −1.57) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

We fitted generalized linear models that included the independent variables and covariates described above. We used generalized estimating equations to account for multiple observations from 1 enrollee and included a plan fixed effect to account for clustered data by plan. We used a 1-part generalized linear model, an identity link, and specified a negative binominal distribution for home health episodes and days and a normal distribution for the proportion of enrollees receiving home health care. All models were weighted by the number of months that subjects were enrolled in their plan. We also performed analyses stratified by the level of copayment increase (≤$14, $15-$19, ≥$20 copayment) and for the following groups: those in the lowest or highest quantile of ZIP code–level income, those with partial Medicaid benefits, and black enrollees.

Disenrollment Analyses

We compared the difference in disenrollment rate between enrollees in case and control plans in the year with the increase of copayments for home health care. We separately estimated the differences in disenrollment rates between case and control plans in 3 levels of home health utilization (none, 1-59 days, and >59 days) prior to copayment increase. We fitted a linear probability model with generalized estimating equations and plan fixed effects.

We stratified disenrollment rates in plans by the level of copayment (ie, <$15, $15-$19, ≥$20). The differences in disenrollment rate between case and control plans were compared within and between different home health copayment levels and levels of baseline utilization.

Estimation of Out-of-Pocket Spending on Home Health Care Associated With Copayment Levels

The data from OASIS include information on admission and discharge dates for home health episodes, but do not include the number of visits associated with a particular episode. We therefore merged 2007 to 2011 OASIS data with Medicare home health claims for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, which report the number of visits per home health episode. Using these merged data, we compared the number of days of home health care for traditional Medicare and MA enrollees; and assessed the correlation between the number of visits and the duration of home health episodes. We also determined the average number of visits and interquartile range (IQR) for the average user of home health care in case plans. By multiplying the estimated number of visits by the copayment for each visit, we derived the potential out-of-pocket costs associated with a particular level of home health copayment.

Results

Characteristics of Enrollees in Case and Control Plans

Prior to the introduction of the copayment, compared with enrollees in control plans, enrollees in case plans were more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities, younger, living in areas with slightly lower income, and have partial Medicaid benefits (Table 1). The magnitudes of these differences were modest.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Medicare Advantage Enrollees in Case and Control Plans.

| Characteristic | Plans | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case (n = 18) | Control (n = 18) | ||

| Enrollees, No. | 135 302 | 155 892 | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 70.9 (9.3) | 72.0 (9.5) | <.001 |

| Female, % | 56.1 | 55.5 | .18 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| White | 78.2 | 78.8 | <.001 |

| Black | 19.1 | 18.8 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.9 | 0.8 | <.001 |

| Asian | 0.6 | 0.5 | <.001 |

| Other | 1.1 | 1.1 | .03 |

| ZIP code–level income, mean (SD), $ | 51 602 (16 640) | 52 528 (18 040) | <.001 |

| Partial Medicaid enrollment, % | 10.7 | 10.0 | <.001 |

Changes in Home Health Utilization in Case and Control Plans

The number of home health days per enrollee during the 12 months before and after the copayment increase is shown in Figure 1. The graph demonstrates parallel trends in utilization in the case and control plans before the introduction of copayments and no visual evidence of a change in utilization in case plans after the introduction of cost sharing. In adjusted analyses, the increased copayment for home health care was not associated with the proportion of enrollees receiving home health care (adjusted difference-in-differences, −0.15; 95% CI, −0.38 to 0.09), the number of home health episodes per user (adjusted difference-in-differences, 0.01; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.03), and home health days per user (adjusted difference-in-differences, −0.19; 95% CI, −3.02 to 2.64) (Table 2). In the plans that introduced home health copayments of $20 or more, the difference-in-differences estimate for the mean number of annual home health episodes was −0.06 (95% CI, −0.11 to −0.02), but the adjusted differences-in-differences for the annual number of health days and the proportion receiving home health care were not significant. We observed no significant reductions in home health utilization for case plans that introduced copayments of $19 or less (Table 2).

Figure 1. Unadjusted Monthly Rate of Home Health Days per Enrollee in the 12 Months Before and 12 Months After the Introduction of Copayments.

Table 2. Changes in the Use of Home Health Services After Introduction of Home Health Copayments in Case and Control Plans.

| Outcomes | Case Plans That Introduced Copayments | Matched Control Plans | Unadjusted Between-Group Difference | Adjusted Between-Group Difference (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Before Copayment Increase | Year With Copayment Increase | Change | Year Before Case Plans Increased Copayment | Year With Increased Copayment in Case Plans | Change | |||

| All Plans | ||||||||

| Proportion of enrollees with home health care, % | 7.46 | 7.76 | 0.30 | 7.23 | 7.48 | 0.25 | 0.05 | −0.15 (−0.38 to 0.09) |

| Home health episodes per user | 1.35 | 1.32 | −0.03 | 1.38 | 1.30 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) |

| Home health days per user | 75.98 | 74.94 | −1.04 | 90.85 | 89.52 | −1.32 | 0.28 | −0.19 (−3.02 to 2.64) |

| Plans With Copayments of $14 or Less | ||||||||

| Proportion of enrollees with home health care, % | 8.05 | 8.65 | 0.59 | 7.62 | 7.90 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.27 (−0.10 to 0.64) |

| Home health episodes per user | 1.36 | 1.33 | −0.03 | 1.45 | 1.29 | −0.15 | 0.12 | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.08) |

| Home health days per user | 78.58 | 80.73 | 2.15 | 99.67 | 97.64 | −2.03 | 4.18 | 0.08 (−4.23 to 4.38) |

| Plans With Copayments of $15-$19 | ||||||||

| Proportion of enrollees with home health care, % | 7.43 | 7.28 | −0.15 | 4.91 | 4.99 | 0.08 | −0.23 | −0.31 (−0.73 to 0.11) |

| Home health episodes per user | 1.34 | 1.32 | −0.02 | 1.28 | 1.26 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.003 (−0.04 to 0.05) |

| Home health days per user | 78.78 | 69.56 | −9.22 | 65.64 | 58.45 | −7.20 | −2.02 | −0.54 (−5.75 to 4.68) |

| Plans With Copayments of $20 or More | ||||||||

| Proportion of enrollees with home health care, % | 6.72 | 7.11 | 0.39 | 8.48 | 8.88 | 0.40 | −0.01 | −0.41 (−0.87 to 0.05) |

| Home health episodes per user | 1.36 | 1.32 | −0.05 | 1.32 | 1.33 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.02) |

| Home health days per user | 68.67 | 71.55 | 2.88 | 87.72 | 89.93 | 2.21 | 0.67 | −0.07 (−5.45 to 5.31) |

In stratified analyses, home health copayments were not associated with significant changes in home health utilization for any population subgroups with the exception of enrollees in the lowest quartile of ZIP code–level income. In this subgroup, the difference-in-differences estimates for the mean number of annual home health episodes and for the annual number of health days were 0.05 (95% CI, 0.004-0.10) and 7.19 (95% CI, 0.26-14.20), respectively, but the estimate for the proportion receiving home health care was not significant (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

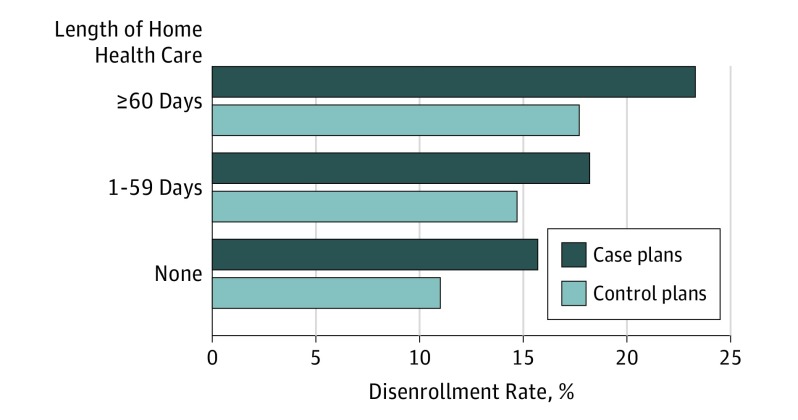

Rates of Disenrollment in Case and Control Plans

During the year that the copayment was introduced, we observed higher disenrollment rates from case plans (17.9%) relative to disenrollment from control plans (13.3%; P < .001). In both case and control plans, the rate of disenrollment increased with greater baseline utilization of home health care. The disenrollment rates were consistently higher in the case plans compared with the control plans across 3 utilization groups (Figure 2). In adjusted analyses, we observed a 5.3 percentage point (95% CI, 4.1-6.5) greater rate of disenrollment in case plans relative to control plans among enrollees who used 1 to 59 days of home health care in the year. We also observed a 6.4 percentage point (95% CI, 4.7-8.1) greater rate of disenrollment in case plans relative to control plans among enrollees using 60 or more days of home health care in the year before the copayment was introduced.

Figure 2. Disenrollment Rates From Case and Control Plans by Duration of Home Health Care During the Year Before the Copayment Increase.

Across every level of copayment and for both case and control plans, we consistently observed an association between greater baseline use of home health services and higher rates of disenrollment (Table 3).

Table 3. Disenrollment Rate Differences Between Case and Control Plans by Level of Copayment Increase and Baseline Level of Home Health Utilization.

| Home Health Care Copay, $ | Group | No. of Patients in Year Before Copayment Increase | Disenrollment Rate in Year With Copayment Increase, % | P Valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1-59 Days | 60 or More Days | None | 1-59 Days | 60 or More Days | |||

| ≤14 | Case | 47 955 | 2327 | 1489 | 14.4 | 15.9 | 22.4 | <.001 |

| Control | 78 992 | 3471 | 2474 | 12.3 | 16.3 | 19.7 | <.001 | |

| 15-19 | Case | 40 510 | 1780 | 1112 | 16.7 | 19.9 | 23.4 | <.001 |

| Control | 32 826 | 1095 | 398 | 8.6 | 12.1 | 16.6 | <.001 | |

| ≥20 | Case | 37 667 | 1654 | 808 | 16.2 | 19.7 | 25.0 | <.001 |

| Control | 33 817 | 1708 | 1111 | 10.1 | 13.0 | 13.6 | <.001 | |

We used a test for linear trend in increasing disenrollment across these three utilization categories to obtain the P values.

Estimation of Out-of-Pocket Spending Associated With Copayment Levels

We found a correlation of 0.8 between the number of days spent in home health care according to OASIS and the number of home health visits as determined by traditional Medicare claims. Among enrollees in traditional Medicare, the average user of home health care received 37 annual visits (IQR, 10-40). Among enrollees in case plans, we estimated the average user received 33 annual visits (IQR, 9-36). Case plans introduced copayments ranging from $5 to $20. A $5 home health visit copayment would translate to approximately $165 in annual out-of-pocket costs for an average user of home health care with an IQR of $45 to $180. A $20 home health visit copayment would translate to $660 in annual out-of-pocket spending of $660 for an average user of home health care, with an IQR of $180 to $720.

Discussion

We examined the association of introducing home health copayments in a large, nationally representative sample of MA enrollees. The plans in this study introduced copayments of $5 to $20 per home health visit, which we estimate would translate to $165 to $660 in out-of-pocket spending for the average user of home health services. Despite cost sharing at these levels, we did not find evidence that introducing home health copayments was associated with reduced use of home health services. In stratified analyses, we found no association between the introduction of copayments and declines in utilization even among plans that introduced the largest copayments and among low-income subgroups. Finally, we found higher disenrollment rates from both case and control plans among enrollees with greater use of home health care.

This study extends evidence to a new service in the cost-sharing literature. Proponents of increasing “skin in the game” for Medicare beneficiaries assert that greater cost sharing encourages patients to consider costs and refrain from using services where the expected value is less than the out-of-pocket expense. For example, the RAND Health Insurance Experiment found that increased cost sharing reduced aggregate health care spending and use. In contrast, our findings suggest that the introduction of home health copayments was not associated with fewer days covered by home health care or lower rates of home health episodes. It may be difficult for elderly patients, particularly those with functional impairments and frailty, to reduce their use of home health care in response to out-of-pocket costs. Home health care may also substitute for visit to a medical facility (where there will likely be a copayment) for therapy, treatment, or minor procedures. Another potential explanation for our results is that the duration and intensity of home health care may be strongly influenced by providers’ decisions and treatment protocols such that patients may not be able to terminate care early or be presented with other alternatives. Thus, our finding that patients did not reduce their use of home health care in the face of substantial increases in out-of-pocket costs is concerning, given prior evidence that out-of-pocket medical spending may crowd out spending on other nonmedical necessities such as food, housing, transportation, and personal care expenses, with adverse consequences for seniors’ health and welfare.

Across every level of copayment and for both case and control plans, we consistently observed an association between greater baseline use of home health services and higher rates of disenrollment. Our findings extend previous work demonstrating that the persons with intensive care needs, including those with prior hospitalizations and long-term and short nursing home stays, are more likely to exit MA plans, compared with those who do not use these services. Further study of the reasons for disenrollment is urgently needed, because the benefits of managed care may be attenuated if patients exit their plans once they have complex medical needs.

Unlike traditional Medicare, MA plans can exercise a number of strategies to reduce health services utilization, such as providing feedback and incentives to providers to reduce utilization, restricting the network of contracted providers, and implementing prior authorization procedures. It is possible that the plans that introduced copayments may have been particularly motivated to reduce home health spending via these techniques. However, despite these available strategies, home health utilization did not decline in these plans relative to concurrent trends in control plans.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that unmeasured differences between case and control plans influenced our results. Second, our study findings may not be generalizable to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Although there are differences between these 2 populations, we found that the duration of home health care was similar among traditional Medicare and MA enrollees in case plans. Third, we do not have claims data from MA plans to directly measure the number of home health visits per MA member. However, among traditional Medicare enrollees, the duration of home health care exhibited a high degree of correlation with the number of home health visits. Furthermore, our estimates of home health utilization in MA plans align with findings from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Conclusions

The introduction of home health copayments among MA plans was not associated with lower use of home health services. More intensive use of home health services was associated with increased rates of disenrollment in MA plans. Our study suggests that imposing copayments does not meaningfully reduce the use of home health services, but may add substantially to the burden of out-of-pocket spending among frail older adults.

eTable 1. Use of Home Health Services among Case and Control Plans with Two Years of Data Prior to Copayment Increase

eTable 2. Difference-in-Difference Estimates in Use of Home Health Services for Enrollees with in Highest Level of Copayment Increase, Black Enrollees, Those Living in the Highest and Lowest Quartile of Area-level Socioeconomic Status, and Those with Partial Dual Eligibility

References

- 1.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) Health care spending and the Medicare program, June 2011. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/june-2016-data-book-health-care-spending-and-the-medicare-program.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2016.

- 2.National Association of Home Care & Hospice President’s budget includes provisions for home health copays, additional payment cuts for post-acute care providers. http://www.nahc.org/NAHCReport/nr140305_1/. Accessed September 6, 2016.

- 3.The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform The moment of truth: Report of the national commission on fiscal responsibility and reform. Washington DC: The White House, December 2010.

- 4.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) Medicare payment policy: Report to the Congress, March 2011. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/Mar11_EntireReport.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed September 6, 2016.

- 5.US Department of Health & Human Services HHS FY 2017. Budget in Brief - CMS – Medicare. http://www.hhs.gov/about/budget/fy2017/budget-in-brief/cms/medicare/index.html. Accessed September 6, 2016.

- 6.Trivedi AN, Rakowski W, Ayanian JZ. Effect of cost sharing on screening mammography in Medicare health plans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):375-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trivedi AN, Swaminathan S, Mor V. Insurance parity and the use of outpatient mental health care following a psychiatric hospitalization. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2879-2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi AN, Moloo H, Mor V. Increased ambulatory care copayments and hospitalizations among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(4):320-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. Patient cost-sharing and hospitalization offsets in the elderly. Am Econ Rev. 2010;100(1):193-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) Report to the Congress: Variation and innovation in Medicare, June 2003.

- 11.Bach PB. Cost sharing for health care—whose skin? Which game? N Engl J Med. 2008;358(4):411-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newhouse JP, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al. Some interim results from a controlled trial of cost sharing in health insurance. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(25):1501-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis K, Stremikis K, Doty MM, Zezza MA. Medicare beneficiaries less likely to experience cost- and access-related problems than adults with private coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1866-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briesacher BA, Ross-Degnan D, Wagner AK, et al. Out-of-pocket burden of health care spending and the adequacy of the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy. Med Care. 2010;48(6):503-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare Advantage and joining Traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1675-1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper AL, Trivedi AN. Fitness memberships and favorable selection in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):150-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Newhouse JP. New risk-adjustment system was associated with reduced favorable selection in medicare advantage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(12):2630-2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser Family Foundation Medicare Advantage 2010. data spotlight: Benefits and Cost-sharing. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8047.pdf. Accessed September 6, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Use of Home Health Services among Case and Control Plans with Two Years of Data Prior to Copayment Increase

eTable 2. Difference-in-Difference Estimates in Use of Home Health Services for Enrollees with in Highest Level of Copayment Increase, Black Enrollees, Those Living in the Highest and Lowest Quartile of Area-level Socioeconomic Status, and Those with Partial Dual Eligibility