Abstract

Crescentic glomerulonephritis (GN) is one of the common causes of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN). Pauci-immune crescentic GN is usually associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). However, patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN who lack ANCAs have recently been reported. Approximately 10–30 % of patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN lack ANCAs. The clinical characteristics of patients with ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic GN are not entirely the same as patients with ANCA-positive GN, and this suggests that ANCA-negative and ANCA-positive pauci-immune crescentic GN might be different disease entities. We report a patient with ANCA-negative crescentic GN complicated with multiple opportunistic infections (Candida albicans, herpes simplex virus, and Cytomegalovirus) in the digestive tract during the course of immunosuppressive therapy. After antifungal and antiviral therapies including itraconazole, valaciclovir, and ganciclovir, she recovered from multiple opportunistic infections. The occurrence of comorbid opportunistic infections during the course of immunosuppressive therapy may not be rare in the elderly. However, a case of multiple opportunistic infections limited to the digestive tract is very rare.

Keywords: Crescentic glomerulonephritis, ANCA-negative, Candida albicans, Herpes simplex virus, Cytomegalovirus, Esophagitis, Colitis, Opportunistic infection

Introduction

Pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis (GN) is one of the common causes of crescentic GN, especially in the elderly. Most patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN have anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), which activates neutrophils, leading to small-vessel vasculitis [1]. However, patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN who lack ANCAs have been reported [2, 3]. Recently, Chen et al. [2, 4] reported that the clinical characteristics of patients with ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic GN are not entirely the same as patients with ANCA-positive GN, and proposed that ANCA-negative and ANCA-positive pauci-immune crescentic GN might be different disease entities.

Opportunistic infection is not a rare complication in patients treated with glucocorticoid therapy. Use of glucocorticoids increases the risk of viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections in various organs, and the risk of infection depends on the dose and duration of treatment [5, 6]. However, it is rare for multiple opportunistic infections in digestive tract to occur in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative and nontransplant patient during treatment with glucocorticoids alone [7].

We report a patient with ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic GN who developed multiple opportunistic infections limited to the digestive tract during the course of treatment with glucocorticoids alone, and discuss the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case report

A 79-year-old woman was referred to the division of nephrology for leg edema lasting for at least a month, microscopic hematuria, and acute worsening of renal function. She had undergone curative gastrectomy 5 years previously. Since then, she had received a medical check-up every 6 months without medication. Five months before admission, her serum creatinine was 0.67 mg/dL, and urinalysis was normal. On admission, her blood pressure was 180/72 mmHg, pulse was 80/min, and temperature was 36.4 °C. Physical examination showed edema of both legs and vesicular breath sounds in the right lower lung. Laboratory test results were: white blood cell count 7.7 × 103/μL, hemoglobin 8.3 g/dL, platelets 139 × 103/μL, serum total protein 6.3 g/dL, serum albumin 3.0 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 36.7 mg/dL, serum creatinine 2.25 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein 1.5 mg/dL. Her serum immunoglobulin and complement levels were: IgG 1,581 mg/dL, IgA 184 mg/dL, IgM 255 mg/dL, C3 50 mg/dL, and C4 21 mg/dL. Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA, proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCA, and anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) antibody were undetectable. An indirect immunofluorescent assay against cytoplasmic and perinuclear ANCA was also negative. Tests for the surface antigen of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and antibodies against hepatitis C virus (HCV) were negative. A serum test for cryoglobulin precipitation was negative. Urinalysis revealed 1+ protein, 4+ occult blood, and 1+ leukocytes and was negative for sugar. Urinary sediment showed more than 100 erythrocytes (including dysmorphic erythrocytes) and 1–4 leukocytes per high-power field. Urinary protein excretion was 0.79 g/day. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the lung revealed reticular pattern in the right lower lung without signs of hemorrhage.

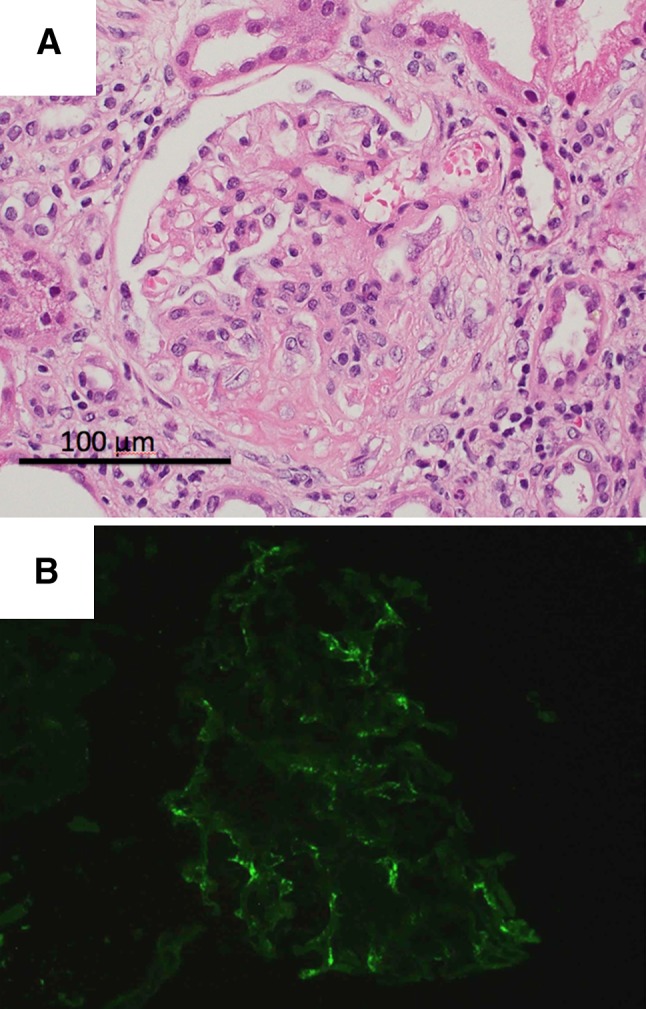

Renal biopsy was performed 7 days after admission. Light microscopic examination revealed 12 glomeruli, of which 7 were globally sclerotic. Among the remaining 5 glomeruli, 3 had fibrocellular crescents, while 2 looked normal (Fig. 1a). Neither mesangial cell proliferation nor mesangial matrix expansion could be seen in any glomerulus. There were focal infiltrations of inflammatory cells composed of lymphocytes and monocytes in the interstitial compartment, together with fibrosis. Neutrophil infiltration was not apparent in the glomeruli or interstitium. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed negative staining for IgG, IgM, C3, and C4, but positive staining for IgA in the mesangium (Fig. 1b). On the basis of these findings, we made a diagnosis of ANCA-negative crescentic GN with IgA deposition.

Fig. 1.

a Light micrographs showing fibrocellular crescent formation [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) ×400]. b Immunofluorescence microscopy showing slight positive staining for IgA in the mesangium

After treatment with intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg/day) pulse therapy for 3 days, oral prednisolone therapy was initiated at dosage of 30 mg/day for 3 weeks. We administered only trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole as preventive agents. The serum creatinine level had worsened to 3.35 mg/dL 14 days after admission, but it finally improved to 1.23 mg/dL after the therapy and the occult blood disappeared. We could also prevent involvement of other organs by the ANCA-negative vasculitis. She was discharged 37 days after admission, and followed up regularly in our outpatient clinic.

Two weeks after discharge, she developed anorexia and nausea. Fever, abdominal pain, and dysphagia were not remarkable. To examine the cause of these symptoms, she was readmitted 1 month after the previous discharge. On admission, her blood pressure was 110/62 mmHg, pulse was 110/min, and temperature was 36.8 °C. She was severely dehydrated. Laboratory test results on the second admission were: white blood cell count 13.6 × 103/μL (91.7 % neutrophils, 4.4 % lymphocytes, 3.4 % monocytes, and 0.5 % eosinophils), hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, platelets 188 × 103/μL, serum total protein 5.1 g/dL, serum albumin 3.2 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 66.3 mg/dL, serum creatinine 3.31 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein 14.6 mg/dL. Her serum immunoglobulin and complement levels were: IgG 517 mg/dL, IgA 90 mg/dL, IgM 61 mg/dL, C3 75 mg/dL, and C4 34 mg/dL. Urinalysis revealed 1+ protein, but was negative for occult blood and leukocytes. Blood culture was negative. CT scans of neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis revealed no signs of lymphadenopathy, pneumonia, pleural effusion, osteomyelitis or abscess formation. She seemed to improve for a while during central venous hyperalimentation. However, anorexia remained. Gastroscopy performed on day 2 demonstrated multiple discrete shallow ulcers with plaques in the middle and lower esophagus (Fig. 2a). A biopsy specimen from the ulcer edge revealed fungal hyphae and spores by Grocott staining (Fig. 2b), and multinucleated giant cells with homogeneous ground-glass intranuclear inclusions characteristic of herpes virus (Fig. 2c) were observed. The culture of the plaque was positive for Candida albicans. Immunohistochemical staining of the specimen for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 and type 2, and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) was not clear. However, both the endoscopic and histologic findings were highly suggestive of herpes esophagitis; we thus diagnosed the patient with Candida and herpes esophagitis. A 2-week course of intravenous itraconazole (200 mg/day) and valaciclovir (1000 mg/day) relieved her symptoms gradually until a week after the initiation of the therapy, when she developed rapidly worsening anorexia, dysphagia, and watery diarrhea. Clostridium difficile toxin A was not detectable in her stool. Gastroscopy performed on day 20 revealed multiple punched-out ulcers in the gastroesophageal junction (Fig. 3a). The findings of discrete shallow ulcers and plaques seen in the previous gastroscopy had disappeared. Colonoscopy performed on day 23 also revealed an annular ulcer in the ascending colon (Fig. 3b). Biopsy specimens from both the esophagus and colon showed multiple large cells with both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions, typical for CMV cytopathic effect. No findings of tuberculosis were seen. Immunohistochemistry for Cytomegalovirus was positive in both specimens (Fig. 4a, b). Positive CMV antigenemia (C7HRP) showing 169 positive cells per 50,000 white blood cells confirmed the diagnosis of CMV esophagitis and colitis. We administered ganciclovir (500 mg/day) for 19 days. After the treatment, her symptoms improved, and she could be discharged 38 days after readmission. Her clinical course after the second admission is outlined in Fig. 5.

Fig. 2.

a Gastroscopy showing multiple discrete shallow ulcers with plaques in the middle and lower esophagus.b Confirmation of Candida esophagitis by Grocott staining (×400). The fungal hyphae and spores were stained. c Herpes simplex virus infection of the esophagus, producing characteristic multinucleated cells with homogeneous ground-glass intranuclear inclusions (H&E ×400)

Fig. 3.

a Gastroscopy showing punched-out ulcers in the gastroesophageal junction. b Colonoscopy revealing an annular ulcer in the ascending colon

Fig. 4.

a Confirmation of Cytomegalovirus esophagitis by CMV immunohistochemistry. The intranuclear viral inclusions were stained brown (×400). b Confirmation of Cytomegalovirus colitis by CMV immunohistochemistry (×400)

Fig. 5.

Clinical course after the second admission

Discussion

The majority of patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN have ANCA seropositivity [1]. Recently, however, cases with ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic GN have been accumulated [2, 3]. Chen et al. [2] reported that, in their study of 85 patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN, approximately 30 % of patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN lacked ANCAs and that there were clinical differences between those with and without ANCA: ANCA-negative patients were younger, had fewer extrarenal symptoms, showed a greater degree of proteinuria, and exhibited poorer renal outcomes than ANCA-positive patients. To explain these differences, they proposed that ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic GN might be a different disease entity from ANCA-positive vasculitis [2, 4]. In our case, both the clinical presentations, such as age at onset and rapidly progressing course of the disease, and the histological findings of crescentic GN without ANCA seropositivity are consistent with this newly proposed disease entity, except for the slight positive staining for IgA in the mesangium. Considering that the IgA deposition did not accompany mesangial cell proliferation or matrix expansion, it is difficult to diagnose the patient with IgA nephropathy or purpura nephritis with crescents. Nonpathogenic IgA deposition in the mesangium is not rare, although the IgA deposition may have some pathogenic role in this case [8]. Therefore, we finally made a diagnosis of ANCA-negative crescentic GN with IgA deposition.

What is interesting in our case is that the patient developed multiple opportunistic infections in the digestive tract during the course of treatment. Opportunistic infection is not a rare complication of immunosuppressive therapy in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), especially in patients treated with prolonged immunosuppression or other immunosuppressants, including cyclophosphamide [9, 10]. In this case, we used only glucocorticoids as induction treatment to avoid the risk of infection. When she was readmitted for multiple opportunistic infections, she was treated with 15 mg prednisolone daily, and the cumulative dose reached 1,315 mg in addition to 1,500 mg methylprednisolone at the initiation of the therapy. A daily dose of 15 mg prednisolone is not believed to cause severe immunosuppression [5, 6]. The cumulative dose including pulse therapy, however, may increase the risk of infection about 2- to 4-fold [5, 11]. In addition, she also had had aggravating factors such as renal dysfunction, old age, undernutrition, proton-pump inhibitor use, and postgastrectomy state [12]. These factors might have predisposed her to develop opportunistic infections. Some studies showed that the risk factors for Candida esophagitis in non-HIV patients were diabetes mellitus, therapy with corticoids, malignancies, broad-spectrum antibodies, liver cirrhosis, and proton-pump inhibitor [13]. However, there have been few cases in which a non-HIV and nontransplant patient developed multiple opportunistic infections limited to the digestive tract during treatment of nephritis with glucocorticoids alone. Mucosal barrier injury by one organism may prompt others to infect. Ulcers of the digestive tract caused by ischemia resulting from angiitis can be sites of infection; however, we could not identify such findings in her biopsy specimens.

The first reason why we chose relatively aggressive treatment was that progressive renal dysfunction and hematuria with dysmorphic erythrocytes were suggestive of high activity of ANCA-negative nephritis. On the other hand, very active lesions, such as cellular crescents or necrotizing glomeruli, were not observed in this biopsy specimen, and the proportion of global sclerosis was high. It is believed that such cases are resistant to aggressive immunosuppressive therapy. In this case, there was a discrepancy between the clinical and biopsy findings. Taking into account the possibility of sampling error, we thought we were permitted to choose relatively aggressive treatment in order to decrease the risk of dialysis. The second reason was that the prognosis of ANCA-negative RPGN is poorer, as compared with that of ANCA-associated RPGN [2]. Bomback et al. reported ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis in the very elderly and showed that elderly patients treated with immunosuppression had significantly lower incidence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) at 1-year biopsy (36 %) compared with untreated patients (73 %), while there was no significant difference in 1-year mortality rate between these groups. However, when follow-up was extended beyond 2 years, immunosuppression was associated with lower risk of death [14]. This conclusion might be true of ANCA-negative glomerulonephritis in the very elderly, although further studies are needed to define appropriate treatment. In this case, we succeeded in protecting renal function and controlling the activity of ANCA-negative nephritis, but our treatment might induce excessive immunosuppression and gut infections. Considering her aggravating factors, we should be more careful of the prednisolone dose and administer preventive agents, such as amphotericin and itraconazole.

In summary, we report a case of ANCA-negative crescentic GN complicated with multiple opportunistic infections in the digestive tract during the course of treatment with glucocorticoids alone. Cases of multiple opportunistic infections limited to the digestive tract are very rare. We could make a diagnosis of Candida, herpes, and CMV esophagitis and colitis. By administration of itraconazole, valaciclovir, and ganciclovir, she recovered. However, we should evaluate whether the benefits of immunosuppression exceed the risk, taking the patient’s background into consideration.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Morgan MD, Harper L, Williams J, Savage C. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm-associated glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1224–1234. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen M, Yu F, Wang SX, Zou WZ, Zhao MH, Wang HY. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-negative pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:599–605. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberger U, Fakhouri F, Vanhille P, Beaufils H, Mahr A, Guillevin L, Lesavre P, Noël LH. ANCA-negative pauci-immune renal vasculitis: histology and outcome. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2005;20:1392–1399. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Kallenberg CG, Zhao MH. ANCA-negative pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:313–318. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuck AE, Minder CE, Frey FJ. Risk of infectious complications in patients taking glucocorticoids. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:954–963. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.6.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutolo M, Seriolo B, Pizzorni C, Secchi ME, Soldano S, Paolino S, Montagna P, Sulli A. Use of glucocorticoids and risk of infections. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;8:153–155. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sendi P, Wolf A, Graber P, Zimmerli W. Multiple opportunistic infections after high-dose steroid therapy for giant cell arteritis in a patient previously treated with a purine analog. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:922–924. doi: 10.1080/00365540500540475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldherr R, Rambausek M, Duncker WD, Ritz E. Frequency of mesangial IgA deposits in a non-selected autopsy series. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 1989;4:943–946. doi: 10.1093/ndt/4.11.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki Y, Takeda Y, Sato D, Kanaguchi Y, Tanaka Y, Kobayashi S, Suzuki K, Hashimoto H, Ozaki S, Horikoshi S, Tomino Y. Clinicoepidemiological manifestations of RPGN and ANCA-associated vasculitides: an 11-year retrospective hospital-based study in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20:54–62. doi: 10.1007/s10165-009-0239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosch X, Guilabert A, Espinosa G, Mirapeix E. Treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298:655–669. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon WG, Abrahamowicz M, Beauchamp ME, Ray DW, Bernatsky S, Suissa S, Sylvestre MP. Immediate and delayed impact of oral glucocorticoid therapy on risk of serious infection in older patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case-control analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1128–1133. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly JP, Blijlevens NM, de Pauw BE. Infections in the immunocompromised host: general principles. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principle and practice of infectious diseases. 7. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2009. pp. 3781–3791. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chocarro Martínez A, Galindo Tobal F, Ruiz-Irastorza G, González López A, Alvarez Navia F, Ochoa Sangrador C, Martín Arribas MI. Risk factors for esophageal candidiasis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s100960050437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bomback AS, Appel GB, Radhakrishnan J, Shirazian S, Herlitz LC, Stokes B, D’Agati VD, Markowitz GS. ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis in the very elderly. Kidney Int. 2011;79:757–764. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]