Abstract

In 2013, OPTN/UNOS mandated that transplant centers collect data on living kidney donors (LKDs) at 6-months, 1-year, and 2-years post-donation, with policy-defined thresholds for the proportion of complete living donor follow-up (LDF) data submitted in a timely manner (60 days before or after the expected visit date). While mandated, it was unclear how centers across the country would perform in meeting thresholds, given potential donor and center-level challenges of LDF. To better understand the impact of this policy, we studied SRTR data for 31,615 LKDs between 1/2010-6/2015, comparing proportions of complete and timely LDF form submissions pre- and post-policy implementation. We also used multilevel logistic regression to assess donor- and center-level characteristics associated with complete and timely LDF submissions. Complete and timely 2-year LDF increased from 33% pre-policy (1/2010-1/2013) to 54% post-policy (2/2013-6/2015) (p<0.001). In an adjusted model, the odds of 2-year LDF increased by 22% per year pre-policy (p<0.001) and 23% per year post-policy (p<0.001). Despite these annual increases in LDF, only 43% (87/202) of centers met the OPTN/UNOS-required 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year LDF thresholds for LKDs who donated in 2013. These findings motivate further evaluation of LDF barriers and the optimal approaches to capturing outcomes after living donation.

Introduction

More than 5,500 individuals become living kidney donors (LKDs) each year in the United States (1). The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) maintains a national registry of LKDs. Much of our current knowledge of post donation outcomes for LKDs comes from studies that have linked this registry to external data sources, including other registries and administrative claims (2–7). Due to incomplete follow-up in the registry, most granular inferences about post-donation and long-term health outcomes have been limited to single-center or small multi-center studies (8–32). A survey published in 2013 reported that approximately 40% of transplant centers lost contact with over 75% of LKDs within 2-years post-donation (33). Barriers to living donor follow-up (LDF) frequently reported by transplant centers include donor inconvenience for medical tests, out-of-date contact information, lack of reimbursement for follow-up services, and direct and indirect costs to donors (33).

In 2013, the OPTN/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) responded to a Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) directive to develop policies regarding living donor care (informed consent, evaluation, and follow-up) in accordance with other OPTN policies (34). This 2013 OPTN/UNOS policy requires transplant centers to achieve specific thresholds for collecting and reporting clinical and laboratory data for LKDs at 6-months, 1-year and 2-years post-donation, respectively (35). For LKDs donating after December 31, 2014, transplant centers are required to report clinical data for 80% and laboratory data for 70% of donors (35).

Given the challenges faced by donors and centers alike and the lack of direct reimbursement mechanisms for follow-up costs (36), we hypothesized that compliance with the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF mandate would vary across centers. To understand the impact of this policy change, we explored the national landscape of LDF and identified donor- and center-level characteristics associated with complete and timely LDF using multilevel logistic regression.

Methods

Data source

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) external release made available in June 2016. The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by members of the OPTN, and has been described elsewhere (2). The HRSA, US Department of Health and Human Services, provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

Study population

We studied 31,615 LKDs who donated between January 1, 2010 and June 30, 2015, 13,496 (42.7%) of whom donated after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF policy on February 1, 2013. Follow-up data through February 29, 2016 were included.

Policy definitions

Transplant centers were encouraged to submit LDF forms before 2013, and required to do so after the policy change. Under the 2013 OPTN/UNOS policy, LDF forms collect data on nine clinical and two laboratory components (35). The clinical components are: vital status, income, loss of medical insurance, recent hospitalizations, kidney-related complications, dialysis, hypertension, diabetes, and cause of death (if applicable). The laboratory components are serum creatinine and urine protein levels. According to the OPTN/UNOS policy definitions, complete LDF forms must contain responses to all clinical and laboratory components and timely LDF forms must be submitted within a 60-days window before or after the 6-month, 1-year, or 2-year donation anniversary. According to the policy guidelines, centers were considered non-compliant if they missed any reporting threshold at any time point.

Policy reporting thresholds

Under the 2013 OPTN/UNOS policy, the minimum reporting thresholds for clinical and laboratory data increased over time. Centers were required to submit clinical data for at least 60% of LKDs and laboratory data for at least 50% of LKDs who donated between February 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013. For donations occurring between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2014, clinical and laboratory data were required to be reported for 70% and 60% of LKDs, respectively. For donations after January 1, 2015, submission of clinical data and laboratory data were required for 80% and 70% of LKDs, respectively.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Using the policy submission guidelines, we studied 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year post-donation LDF. We excluded donors with insufficient post-donation follow-up time, restricting analyses of 2-year LDF to 2013 LKDs and 1-year LDF to 2013 and 2014 LKDs. For complete reporting, centers were required to capture only vital status for donors who died. Donors who died prior to the end of a given follow-up window (60 days after their expected visit date) were considered eligible for LDF at that time point and ineligible for future time points. Donors who were marked lost to follow-up for any time period were considered eligible for future follow-up time points.

Statistical Analysis

We used multilevel logistic regression to measure: a) the association between the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy implementation and complete and timely LDF form submission and b) the association of donor- and center-level characteristics with incomplete or non-timely LDF.

We modeled change in LDF in two ways, allowing for different assumptions about the underlying temporal trends. The first set of models used a policy period indicator to estimate the effect of the policy period (pre vs post). These models calculated the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of complete and timely LDF, after adjusting for calendar time and donor- and center-level characteristics (described below). An aOR above 1 indicated that there was a higher chance of complete and timely LDF in the post-implementation period, after adjusting for relevant covariates. The second set of models used a difference-in-differences (DID) framework to estimate the marginal change in the rate of LDF by policy period and allowing the LDF rate to differ by policy period (pre vs post). This DID model captured not only direct policy-related changes in LDF measured post-implementation, but also potential policy-related changes that occurred prior to actual implementation while the policy was being discussed and considered. A ratio of marginal change above 1 indicated that the LDF rate grew faster after the policy was implemented.

Functional forms of categorical variables were chosen using commonly published standards or residual plot analyses. The specifications of the random effects models were assessed using likelihood-ratio tests. Confidence intervals were reported as per the method of Louis and Zeger (37). All analyses were performed using Stata 14.2/MP for Linux (College Station, TX).

Model specification

We adjusted for donor characteristics, including age, sex, race (African-American vs. non-African-American), ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic), geographic location relative to the transplant center (in-state, out-of-state, or international), educational attainment (high school or lower, attended college, college degree, or post-graduate degree), marital status (single, married, divorced/separated, or widowed), relationship to the kidney recipient (spouse, non-spousal family member, kidney exchange participant, or other), employment status, insurance status, history of hypertension, history of smoking, body mass index (BMI), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) immediately prior to donation. We also adjusted for center characteristics, including LKD program size (defined as the median number of LKDs per year during the study period). Recipient characteristics (age, sex, race, and insurance status) were examined during exploratory data analyses and excluded from our final models as they did not appear to confound the associations of interest. All statistical models contained random intercepts to adjust for center-based clustering. The addition of a third level to adjust for region-based clustering was explored but was excluded from the final models as there was no observed variance across regions. After exploring levels and patterns of missingness in both the general study population and the post-policy subgroup, we assumed that these covariates were missing-at-random (MAR). We imputed missing covariate values using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) incorporating fully conditional specification of prediction equation (38). For sensitivity analyses, we restricted to complete-cases (LKDs with no missing baseline covariates).

Results

Study Population

Compared to the pre-policy period (January 2010 – January 2013), LKDs in the post-policy period (February 2013 – June 2015) were less likely to be biological relatives of the recipient and were more likely to be older (≥65 years old), insured, employed, and college educated, have a history of smoking, history of hypertension, lower pre-donation eGFR, and live outside the US (Table 1). Of 31,615 LKDs in our study population, 26,301 (83%) had no missing baseline covariates. The characteristics with the highest levels of missing data were insurance status (9%) and education (6%). Of the 13,496 LKDs who donated post-policy, 12,227 (91%) had no missing baseline covariates. In this group, the characteristics with the highest levels of missing data were also insurance status (4%) and education (4%).

Table 1. LKD characteristics in the United States, before and after 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy implementation.

| LKD Characteristic | Pre-Implementation (January 2010 – January 2013) |

Post-Implementation (February 2013 – June 2015) |

p-value1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 18,119 | 13,496 | |

| Female | 62% | 62% | 0.6 |

| Age category | <0.001 | ||

| 18–34 | 29% | 30% | |

| 35–54 | 55% | 53% | |

| 55–64 | 14% | 15% | |

| 65+ | 2% | 3% | |

| African-American | 11% | 11% | 0.1 |

| Hispanic | 14% | 14% | 0.4 |

| History of hypertension | 3% | 4% | <0.01 |

| History of smoking | 25% | 27% | <0.001 |

| BMI category | 0.4 | ||

| <19 | 2% | 1% | |

| 19–24 | 34% | 33% | |

| 25–29 | 42% | 43% | |

| ≥30 | 22% | 23% | |

| eGFR prior to donation2 | <0.01 | ||

| 0–80 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 14% | 14% | |

| 80–99 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 34% | 36% | |

| ≥100 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 52% | 50% | |

| Educational attainment | <0.001 | ||

| Post-college graduate | 13% | 15% | |

| College degree | 29% | 32% | |

| Attended college | 29% | 26% | |

| High School or less | 29% | 27% | |

| Marital status | 1.0 | ||

| Married/life partner | 63% | 63% | |

| Single | 27% | 27% | |

| Divorced/separated | 9% | 9% | |

| Widowed | 1% | 1% | |

| Relationship to recipient | <0.001 | ||

| Spouse | 13% | 13% | |

| Non-spousal family member | 52% | 49% | |

| KPD | 13% | 16% | |

| Other | 22% | 22% | |

| Employed prior to donation | 82% | 83% | 0.049 |

| Insured prior to donation | 84% | 87% | <0.001 |

| Geographic location (relative to transplant center) | <0.001 | ||

| In-state | 70% | 67% | |

| Out-of-state | 27% | 27% | |

| International | 3% | 6% |

p-values obtained by χ2 test

Calculated using CKD-EPI creatinine equation (2009)

Proportions of 2-year LDF by policy period

The proportion of complete and timely LDF form submissions increased each year between 2010 and 2015 for clinical and laboratory data for 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year LDF (Figure 1). Post-policy, complete and timely 2-year LDF increased independently for clinical data (49% to 65% of LKDs, p<0.001) and for laboratory data (37% to 56% of LKDs, p<0.001) (Table 2). For clinical data, the level of 2-year LDF reporting in the post-policy period varied by component from vital status (73%), readmission since last visit (68%), kidney complications (68%), maintenance dialysis (68%), diabetes (68%), working for income (67%), hypertension (66%), to cause of death (when applicable) (50%). For laboratory data, reporting was higher for serum creatinine (60%) than urine protein (56%) for 2-year LDF post-policy. Complete and timely submission of both clinical and laboratory data together, the primary outcome, increased from 33% to 54% post-policy for 2-year LDF (p<0.001).

Figure 1. Timely and complete LDF for LKDs January 2010 – June 2015.

The proportion of timely and complete LDF forms increased every year for each form type. Timely and complete 6-month LDF form submissions increased from 45% for clinical forms in 2010 to 81% in 2015. Similarly, timely/complete submissions for 6-month laboratory forms increased from 36% in 2010 to 76% in 2015.

Table 2. Proportions of complete and timely LDF, before and after 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy implementation.

| Pre-implementation (January 2010 – January 2013) |

Post-implementation (February 2013 – June 2015) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Complete and Timely LDF Component1 |

6 months N=18,119 |

1 year N=18,115 |

2 years N=18,110 |

6 months N=13,496 |

1 year4 N=11,652 |

2 years5 N=6,181 |

| Vital Status (Alive or Died) | 69% | 71% | 63% | 83% | 78% | 73% |

| Working for Income (Yes or No) | 55% | 56% | 51% | 77% | 73% | 67% |

| Readmission since last Visit (Yes or No) | 65% | 64% | 56% | 81% | 75% | 68% |

| Kidney Complications (Yes or No) | 65% | 64% | 56% | 81% | 75% | 68% |

| Maintenance Dialysis (Yes or No) | 64% | 64% | 56% | 80% | 75% | 68% |

| Developed Hypertension (Yes or No) | 62% | 61% | 53% | 79% | 74% | 66% |

| Diabetes (Yes or No) | 64% | 63% | 55% | 80% | 75% | 68% |

| Cause of Death2 | 50% | 20% | 39% | 50% | 100% | 50% |

|

| ||||||

| Complete Clinical Data | 53% | 53% | 49% | 76% | 71% | 65% |

|

| ||||||

| Serum Creatinine | 53% | 49% | 43% | 75% | 69% | 60% |

| Urine Protein3 | 44% | 41% | 37% | 72% | 66% | 56% |

|

| ||||||

| Complete Laboratory Data | 43% | 40% | 37% | 72% | 65% | 56% |

|

| ||||||

| Complete Clinical and Laboratory Data | 37% | 35% | 33% | 68% | 62% | 54% |

Loss of medical insurance excluded; this variable was not included in the SRTR 2016 Quarter 2 external release

If applicable

Urine protein or protein-creatinine ratio

Excludes donors in 2015

Excludes donors in 2014–2015

Changes in LDF form submission post-policy

LDF increased each year from 2010 to 2015 in all analytical models. In the indicator model, the post-policy period was associated with higher odds of complete and timely 6-month (aOR: 1.611.781.96), 1-year (aOR: 1.361.511.67), and 2-year LDF (aOR: 1.091.211.35) (Table 3). In the DID model, the pre-policy odds of complete and timely 6-month LDF increased by 20% (aOR: 1.191.201.22) per year. Post-policy, the rate of change increased 78% per year (aOR: 1.291.321.36) and this marginal change was statistically significant (p<0.01) (Table 4). Post-policy, the odds of 1-year LDF increased by 29% (aOR: 1.251.291.34) per year, and the odds of 2-year LDF increased by 23% (aOR: 1.131.231.36) per year. The rate of change in complete and timely 1-year and 2-year LDF were not statistically different in the pre- vs post-policy periods (marginal change ratio p=0.2 and p=0.4, respectively). The donor characteristics associated with increased odds of 2-year LDF were consistent across both the indicator and marginal change models and include female sex, younger age, college-level education or higher, and residence in the same state as the transplant center. There were no differences in inferences between the primary results using multiple imputation and the complete-case sensitivity analyses (data not shown).

Table 3. LDF form submission after the implementation of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy compared to before the LDF policy.

These models assume a linear temporal trend over the entire study period and a constant effect of the OPTN/UNOS LDF policy in the post-implementation period. This model provides the odds ratio (OR) of complete and timely LDF in the post-implementation period compared to the pre-implementation period. In both the unadjusted and adjusted models, complete and timely submission of LDF forms increased for all form types after the implementation of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy.

| Complete and Timely LDF |

Unadjusted1 OR (p-value) |

Adjusted2 OR (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| 6-month | 1.60 1.76.1.95 (<0.001) | 1.61 1.78 1.96 (<0.001) |

| 1-year | 1.36 1.50 1.67 (<0.001) | 1.36 1.51 1.67 (<0.001) |

| 2-year | 1.09 1.20 1.34 (<0.001) | 1.09 1.21 1.35 (<0.001) |

Unadjusted for donor-level characteristics.

Models adjusted for donor demographics, BMI, history of hypertension, history of smoking, eGFR, education status, marital status, relationship to recipient, employment status, income status, geographic location, and median LKD program size.

Table 4. Change in the rate of LDF after implementation of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS policy.

These difference-in-differences models assess separate associations with calendar time before and after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF policy on February 1, 2013 using linear splines. For example, from the unadjusted model, 2-year LDF increased by 22% each year prior to the implementation of the policy, and 37% each year after the implementation of the policy, but this marginal change was not statistically different (p=0.5). In both the unadjusted and adjusted models, there was a statistically significant increase in the rate of timely and complete 6-month LDF following the implementation of the 2013 LDF policy, but no evidence of a difference in LDF at 1- and 2-years.

| Unadjusted1 | Adjusted2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Complete and Timely LDF |

Pre-Policy Annual Change3 |

Post-Policy Annual Change |

Marginal Change p-value |

Pre-Policy Annual Change |

Post-Policy Annual Change |

Marginal Change p-value |

| 6-month | 1.181.201.21 | 1.281.321.35 | <0.01 | 1.191.201.22 | 1.291.321.36 | <0.01 |

| 1-year | 1.181.191.21 | 1.241.291.33 | 0.2 | 1.181.201.22 | 1.251.291.34 | 0.2 |

| 2-year | 1.201.221.23 | 1.131.231.35 | 0.5 | 1.211.221.24 | 1.131.231.36 | 0.4 |

Unadjusted for donor-level characteristics.

Models adjusted for donor demographics, BMI, history of hypertension, history of smoking, eGFR, education status, marital status, relationship to recipient, employment status, income status, geographic location, and median LKD program size.

The annualized change was calculated by dividing the estimated rate of LDF from the DID models by the number of years in that time period (i.e. 3.08 years pre-policy and 2.42 years post-policy).

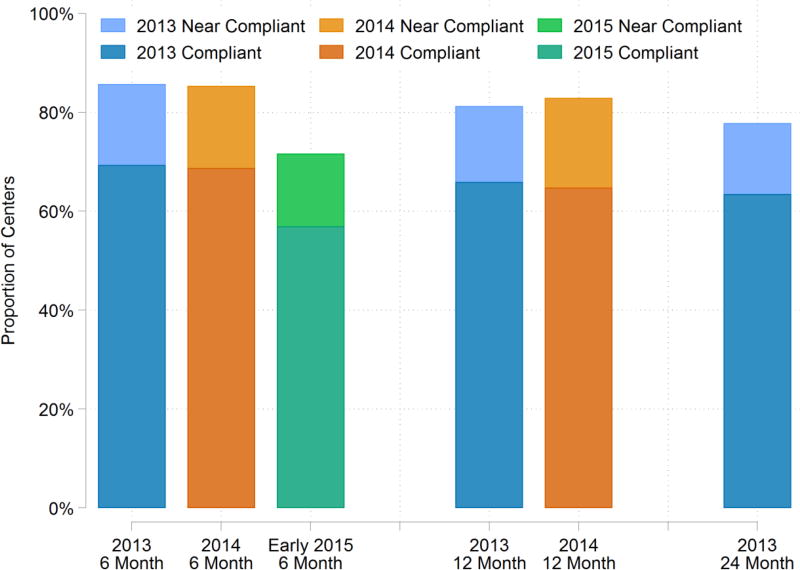

Center LDF submission by policy-defined thresholds

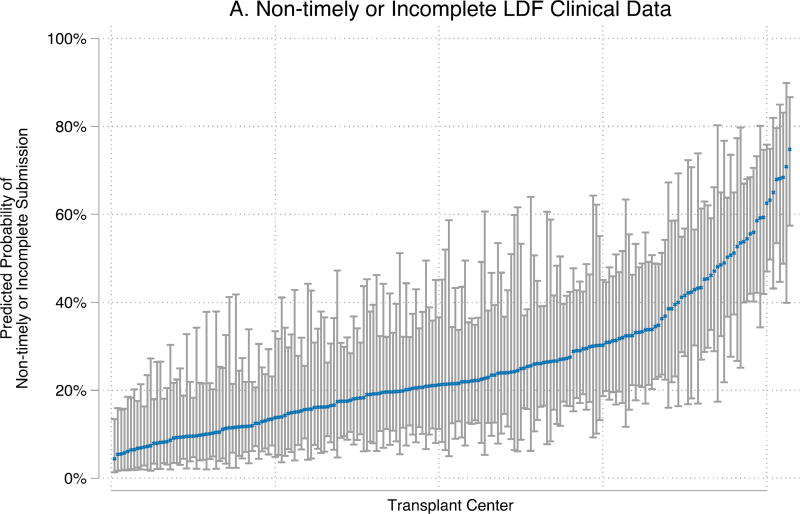

Only 43% (87/202) of centers submitted complete and timely 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year LDF forms that met the policy-defined thresholds for 2013 LKDs. (Table 5). An additional 23% of centers (46/202) submitted complete LDF forms for 2013 LKDs at the policy-defined threshold level outside the required reporting time window. Among centers not meeting policy-defined thresholds for 2013 LKDs, the median proportion of complete and timely 2-year LDF was 59% (IQR: 41–79%) for clinical data and 50% (IQR: 33–67%) for laboratory data (Figure 3). Fifty-five percent (113/204) of centers submitted complete and timely 6-month and 1-year LDF forms at the level required by the policy for LKDs in 2014, and 57% (108/190) met required thresholds for 2015 LKDs. Among centers not meeting policy requirements for LDF, the proportion of complete and timely LDF ranged from 0% to the threshold of compliance. Of these centers, 65% fell below the minimum thresholds due to incomplete forms.

Table 5. Center compliance with 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy.

In order to meet the requirements of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy, a transplant center has to submit timely and complete 6-month, 1-, and 2-year LDF forms. Full compliance with this policy can only be ascertained for the 2013 cohort, but data from the 2014 and 2015 cohorts are shown for reference. The 2015 cohort only includes LKDs from January – June 2015, so it is possible that the proportion of centers meeting compliance thresholds will change as more data become available.

| Donation year |

6-month LDF compliance – N (%) |

6-month & 1-year LDF compliance – N (%) |

6-month, 1-, & 2-year LDF compliance – N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (N=202) | 140 (69%) | 117 (58%) | 87 (43%) |

| 2014 (N=204) | 140 (69%) | 113 (55%) | Data not available |

| 2015 (N=190) | 108 (57%) | Data not available | Data not available |

Figure 3. Distribution of timely and complete LDF among transplant centers for LKDs February 2013 – June 2015.

The variation in LDF form submission among centers persisted over time. A number of non-compliant centers were close to meeting the minimum thresholds for compliance, but several centers fell far below these requirements even as the thresholds increased each year. The minimum thresholds were 60% for clinical data and 50% for lab data on LKDs who donated in 2013, 70% for clinical data and 60% for lab data on LKDs who donated in 2014, and 80% for clinical data and 70% for lab data on LKDs who donated in 2015.

Incomplete or non-timely 6-month LDF post-policy

Centers were more likely to submit incomplete or non-timely clinical 6-month LDF data forms with clinical data for LKDs who were aged 18–34 (aOR vs ages 35–54: 1.141.271.42), had a history of smoking (aOR vs no smoking: 1.071.181.30), had a high school education or less (aOR vs. college degree: 1.0041.131.27), were single (aOR vs married: 1.101.231.38), were a non-spousal family member of the recipient (aOR vs spouse: 1.101.281.49), were not related to the recipient (aOR vs spouse: 1.021.211.43), were not employed at the time of donation (aOR vs. employed: 1.011.141.28), lived out-of-state (aOR vs in-state: 1.121.241.37), or lived outside the US (aOR vs in-state: 1.461.742.08) (Table 6). LKDs followed by centers with a median program size of 45–86 donors per year (quartile 3) had a 70% higher odds or non-timely or incomplete clinical data submission (aOR vs 1–19 LKDs per year: 1.041.662.64).

Table 6. Characteristics associated with non-timely or incomplete 6-month LDF form submission after the implementation of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015).

| Clinical | Lab | Combined | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Characteristic | aOR | p-value | aOR | p-value | aOR | p-value |

| Male | 0.991.081.19 | 0.1 | 1.101.201.31 | <0.001 | 1.051.141.24 | <0.001 |

| Age category (reference: 35–54) | ||||||

| 18–34 | 1.141.271.42 | <0.001 | 1.171.291.44 | <0.001 | 1.181.301.44 | <0.001 |

| 55–64 | 0.720.830.96 | 0.01 | 0.640.730.84 | <0.001 | 0.670.760.87 | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 0.510.690.94 | 0.02 | 0.450.600.80 | <0.001 | 0.450.590.78 | <0.001 |

| African-American | 0.921.061.23 | 0.4 | 0.901.031.18 | 0.7 | 0.941.071.22 | 0.3 |

| Hispanic | 0.810.941.08 | 0.4 | 0.700.800.91 | <0.001 | 0.730.830.95 | 0.01 |

| Month (one-unit change) | 0.620.660.70 | <0.001 | 0.660.700.75 | <0.001 | 0.640.680.72 | <0.001 |

| History of hypertension | 0.660.861.11 | 0.3 | 0.660.841.07 | 0.2 | 0.670.851.07 | 0.2 |

| History of smoking | 1.071.181.30 | <0.001 | 1.071.181.29 | <0.001 | 1.091.191.30 | <0.001 |

| BMI category (reference: 19–24) | ||||||

| <19 | 0.861.221.72 | 0.3 | 0.961.341.87 | 0.1 | 0.891.241.72 | 0.2 |

| 25–29 | 0.991.101.22 | 0.1 | 1.011.111.22 | 0.03 | 1.031.131.24 | 0.01 |

| ≥30 | 0.911.031.16 | 0.7 | 1.061.181.32 | <0.001 | 1.031.151.28 | 0.02 |

| Donor eGFR1 category prior to donation (reference: ≥100) | ||||||

| <80 | 0.840.981.14 | 0.8 | 0.901.031.19 | 0.7 | 0.891.021.17 | 0.8 |

| 80–99 | 0.870.971.07 | 0.5 | 0.840.921.02 | 0.1 | 0.890.981.08 | 0.7 |

| Educational attainment (reference: college degree) | ||||||

| Post-college graduate degree | 0.850.991.14 | 0.9 | 0.871.001.14 | >0.9 | 0.901.031.17 | 0.7 |

| Attended college | 0.941.061.20 | 0.3 | 0.911.011.13 | 0.8 | 0.931.031.15 | 0.6 |

| High school or less | 1.001.141.28 | 0.04 | 1.041.161.31 | 0.01 | 1.051.171.31 | 0.01 |

| Marital status (reference: married) | ||||||

| Single | 1.111.241.38 | <0.001 | 1.021.141.26 | 0.02 | 1.031.141.26 | 0.01 |

| Divorced/separated | 0.971.131.32 | 0.1 | 0.901.041.21 | 0.6 | 0.891.031.19 | 0.7 |

| Widowed | 0.530.871.44 | 0.6 | 0.671.051.65 | 0.8 | 0.570.891.39 | 0.6 |

| Relationship to Recipient (reference: spouse) | ||||||

| Non-spousal family member | 1.101.281.49 | <0.001 | 1.241.431.65 | <0.001 | 1.221.411.62 | <0.001 |

| Kidney exchange (KPD) | 0.991.181.41 | 0.1 | 1.101.301.54 | <0.001 | 1.071.261.48 | 0.01 |

| Other | 1.011.201.42 | 0.03 | 1.101.281.51 | <0.001 | 1.111.291.51 | <0.001 |

| Not working for Income | 1.021.151.29 | 0.02 | 0.981.091.23 | 0.1 | 1.011.131.26 | 0.03 |

| Not insured | 0.911.051.20 | 0.5 | 0.931.051.20 | 0.4 | 0.951.081.23 | 0.2 |

| Geographic location (reference: In-state) | ||||||

| Out-of-State | 1.131.251.39 | <0.001 | 1.261.381.53 | <0.001 | 1.291.421.56 | <0.001 |

| International | 1.501.792.14 | <0.001 | 1.431.692.01 | <0.001 | 1.421.682.00 | <0.001 |

| Median LKD program size (reference: quartile 1: 1–19 LKDs/year) | ||||||

| Quartile 2: 20–44 LKDs/year | 0.761.081.55 | 0.7 | 0.711.001.42 | >0.9 | 0.721.061.54 | 0.8 |

| Quartile 3: 45–86 LKDs/year | 1.051.672.65 | 0.03 | 0.801.251.96 | 0.3 | 0.891.462.38 | 0.1 |

| Quartile 4: ≥87 LKDs/year | 0.741.302.30 | 0.4 | 0.851.472.57 | 0.2 | 0.811.492.74 | 0.2 |

Calculated using CKD-EPI creatinine equation (2009)

Similarly, transplant centers were more likely to submit non-timely or incomplete 6-month LDF forms with laboratory data for LKDs who were male (aOR vs female: 1.111.211.31), aged 18–34 (aOR vs aged 35–54: 1.171.301.44), had BMI between 25–29 (aOR vs BMI 19–24: 1.011.111.22), had a high school education or less (aOR vs. college degree: 1.041.171.30), single (aOR vs married: 1.011.131.25), were a non-spousal family member of the recipient (aOR vs spouse: 1.241.431.65), participated through a kidney exchange (aOR vs spouse: 1.111.311.55), were not related to the recipient (aOR vs spouse: 1.101.291.51), lived out-of-state (aOR vs in-state: 1.241.371.51), or lived outside the US (aOR vs in-state: 1.401.661.97) (Table 6). There were no differences in inferences drawn between the primary results and the complete-case sensitivity analyses (data not shown).

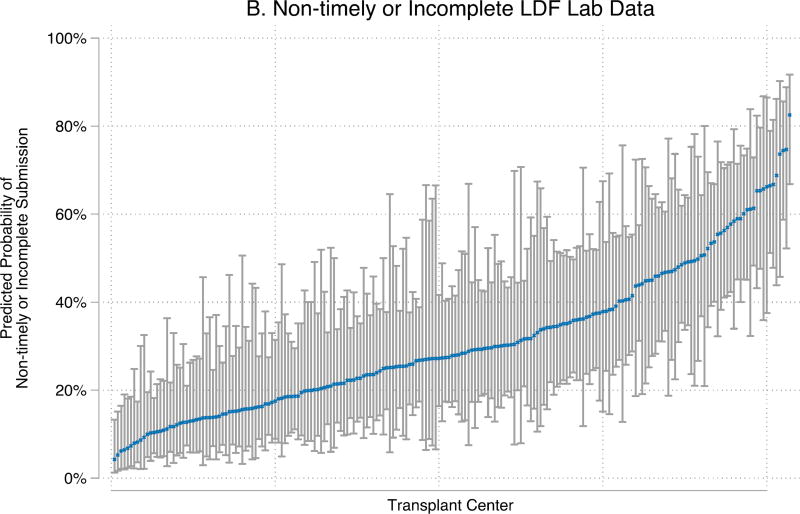

Center-level variation in LDF form submission

The odds of non-timely or incomplete LDF form submission varied significantly by center (p<0.001) (Figure 4). For 6-month LDF, center-level variation accounted for 19% and 20% (inter-class correlation (ICC): 0.150.190.24; 0.160.200.25) of the variance of non-timely or incomplete submission of clinical and laboratory data, respectively.

Figure 4. Transplant center-level variability in non-timely or incomplete 6-month LDF for LKDs February 2013 – June 2015.

Center-level probabilities for a reference donor are represented by dots and calculated from empirical Bayes estimates. The reference donor is female, between 35–54 years old, non-African-American, non-Hispanic, had no history of hypertension or smoking prior to donation, married, spouse of kidney recipient, obtained a college degree, was working for income at the time of donation, was insured at the time of donation, had BMI between 19–24 at the time of donation, had eGFR ≥ 100 prior to donation, went to a small transplant center (1–19 donors/year), donated in 2015, and currently lives in-state. These figures demonstrate that the same donor could have had very different experiences with LDF depending on which transplant center she attended.

Discussion

In this study of national registry data, we found that the proportion of complete and timely LDF form submission increased each year between 2010 and 2015. The proportion of LKDs with complete and timely 2-year LDF increased from 33% to 54% after the implementation of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS LDF policy. Our DID model showed a pre-policy increase in LDF of 20% per year for 6-month and 1-year LDF and 22% per year for 2-year LDF. These pre-policy increases in LDF may be attributable to the public comment process and consensus conferences (39). Despite increases in LDF, only 43% of centers met all the policy requirements for 2013 LKDs.

Studies have shown that post-donation follow-up presents logistical and financial challenges for both donors and centers (33, 40). Despite the 2013 policy change, these barriers remain as there is no formal mechanism to reimburse donors or centers for the costs of complying with this LDF mandate. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Provider Manual revisions clarified that the 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up required by the OPTN/UNOS are not allowable as organ acquisition costs on the Medicare Cost Report, and cannot be billed to the recipient’s Medicare as routine or complication-related care (36). Thus, options for covering the costs of follow-up for donors to Medicare beneficiaries include requiring donors to use their own insurance, or establishing separate charitable funds for centers attempting to legally cover follow-up costs for their donors.

Center-based initiatives to provide long-term donor follow-up and support through integrated laboratory and clinical monitoring, expansion of preventive health strategies, and social networks between past, current and future donors are being pilot tested (41). A recent single-center study suggests that initiatives with dedicated program resources can result in more accurate and complete follow-up (42). In addition, the SRTR has recently enrolled several transplant centers in a HRSA-sponsored pilot “Living Donor Collective” to test the feasibility of LDF through the SRTR. Finally, efforts could be made to clarify that the National Organ Transplant Act prohibition on ‘valuable consideration’ for an organ does not include the provision of routine, mandated follow-up care.

In conclusion, 57% of transplant centers did not meet national reporting thresholds under the 2013 OPTN/UNOS mandate despite yearly increases in LDF since 2010. This study was not able to determine additional barriers to LDF submission; however, the identification of donor- and center-level characteristics associated with non-timely or incomplete might inform future studies. Another limitation of this study was the availability of follow-up data since the implementation of the 2013 OPTN/UNOS policy. Center-level compliance with the policy could only be assessed for 2013 LKDs. However, since the OPTN/UNOS policy requires all thresholds to be met, we show that only 55% of centers have the potential to meet the policy-defined thresholds for 2014 LKDs (Table 5). Future research is needed to define the optimal time points, data elements, form of data capture, and most effective implementation strategies to systematically capture and study outcomes after living kidney donation.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Change in Complete and Timely 6-month LDF Form Submission Associated with Post-Policy Implementation (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S2: Change in Complete and Timely 1-year LDF Form Submission Associated with Post-Policy Implementation (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S3: Change in Complete and Timely 2-year LDF Form Submission Associated with Post-Policy Implementation (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S4: Marginal Change Post-Policy Implementation Associated with Complete and Timely 6-month LDF Form Submission (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S5: Marginal Change Post-Policy Implementation Associated with Complete and Timely 1-year LDF Form Submission (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S6: Marginal Change Post-Policy Implementation Associated with Complete and Timely 2-year LDF Form Submission (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S7: Characteristics Associated with in Incomplete and Non-timely 6-month LDF form submission after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015)

Table S8: Characteristics Associated with in Incomplete and Non-timely 1-year LDF form submission after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015)

Table S9: Characteristics Associated with in Incomplete and Non-timely 2-year LDF form submission after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015)

Figure S1: Timeliness of LDF form submissions for donations January 2010 – June 2015

Figure 2. Proportion of transplant centers compliant with LDF form submission for LKDs February 2013 – June 2015.

Some transplant centers submitted complete information outside of the 120-day reporting period. These centers were marked as near compliant in the figure. Some centers were compliant with 6-month LDF for the 2013 cohort but non-compliant for a later LDF reporting time. On the other hand, some centers were non-compliant with 6-month LDF reporting but compliant with later time points. Thus, while there seems to be little change in the proportion of transplant centers in the 2013 cohort between 6-month, 1-, and 2-year follow-up, only 43% of centers were fully compliant in this cohort.

Acknowledgments

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR, UNOS/OPTN, or the US Government. Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Grant Numbers 4R01DK096008-04, 5K01DK101677-02, and 5K24DK101828-03, 1F32DK109662-01 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Grant Number K01HS024600.

Abbreviations

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- BMI

body mass index

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- DID

difference-in-differences

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- ICC

interclass correlation

- LKD

living kidney donor

- LDF

living donor follow-up

- MAR

missing at random

- MICE

multiple imputation by chained equations

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.OPTN/UNOS. National Data Reports, Transplants by Donor Type. 2017 Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/#.

- 2.Massie AB, Kuricka L, Segev DL. Big data in organ transplantation: registries and administrative claims. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1723–1730. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Saab G, Salvalaggio PR, Axelrod D, et al. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(8):724–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Axelrod D, Davis CL, McCabe M, et al. Depression Diagnoses after Living Kidney Donation: Linking United States Registry Data and Administrative Claims. Transplantation. 2012;94(1):77. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318253f1bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, Mehta SH, Singer AL, Taranto SE, et al. Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2010;303(10):959–966. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Luo X, Kumar K, Brown RS, et al. Outcomes of live kidney donors who develop end-stage renal disease. Transplantation. 2016;100(6):1306–1312. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, Montgomery RA, McBride MA, Wainright JL, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579–586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lentine KL, Segev DL. Understanding and Communicating Medical Risks for Living Kidney Donors: A Matter of Perspective. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2016 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016050571. ASN. 2016050571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn JF, Nylander WA, Jr, Richie RE, Johnson HK, MacDonell RC, Jr, Sawyers JL. Living related kidney donors. A 14-year experience. Annals of surgery. 1986;203(6):637. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198606000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Elinder C-G, Stenbeck M, Tydén G, Groth C-G. Kidney Donors Live Longer. Transplantation. 1997;64(7):976–978. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matas AJ, Payne WD, Sutherland DE, Humar A, Gruessner RW, Kandaswamy R, et al. 2,500 living donor kidney transplants: a single-center experience. Annals of surgery. 2001;234(2):149–164. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller IJ, Suthanthiran M, Riggio RR, Williams JJ, Riehle RA, Vaughan ED, et al. Impact of renal donation. Long-term clinical and biochemical follow-up of living donors in a single center. The American journal of medicine. 1985;79(2):201–208. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizvi SAH, Naqvi SAA, Jawad F, Ahmed E, Asghar A, Zafar MN, et al. Living kidney donor follow-up in a dedicated clinic. Transplantation. 2005;79(9):1247–1251. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000161666.05236.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siebels M, Theodorakis J, Schmeller N, Corvin S, Mistry-Burchardi N, Hillebrand G, et al. Risks and complications in 160 living kidney donors who underwent nephroureterectomy. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2003;18(12):2648–2654. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borchhardt KA, Yilmaz N, Haas M, Mayer G. Renal funcation and glomergular permselectivity late after living related donor transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;62(1):47–51. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199607150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chavers BM, Michael AF, Welland D, Najarlan JS, Mauer SM. Urinary albumin excretion in renal transplant donors. The American journal of surgery. 1985;149(3):343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(85)80104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiesel M, Carl S, Staehler G, editors. Transplantation proceedings. Elsevier; 1997. Living donor nephrectomy: a 28-year experience at Heidelberg University. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toronyi E, Alföldy F, Jaray J, Remport A, Hidvegi M, Dabasi G, et al. Evaluation of the state of health of living related kidney transplantation donors. Transplant International. 1998;11(S1) doi: 10.1007/s001470050426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahous SA, Stephan A, Blacher J, Safar ME. Aortic stiffness, living donors, and renal transplantation. Hypertension. 2006;47(2):216–221. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000201234.35551.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hakim RM, Goldszer RC, Brenner BM. Hypertension and proteinuria: long-term sequelae of uninephrectomy in humans. Kidney international. 1984;25(6):930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talseth T, Fauchald P, Skrede S, Djøseland O, Berg KJ, Stenstrøm J, et al. Long-term blood pressure and renal function in kidney donors. Kidney international. 1986;29(5):1072–1076. doi: 10.1038/ki.1986.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres VE, Offord KP, Anderson CF, Velosa JA, Frohnert PP, Donadio JV, et al. Blood pressure determinants in living-related renal allograft donors and their recipients. Kidney international. 1987;31(6):1383–1390. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gossmann J, Wilhelm A, Kachel HG, Jordan J, Sann U, Geiger H, et al. Long-Term Consequences of Live Kidney Donation Follow-Up in 93% of Living Kidney Donors in a Single Transplant Center. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(10):2417–2424. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson CF, Velosa JA, Frohnert PP, Torres VE, Offord KP, Vogel JP, et al., editors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 1985. The risks of unilateral nephrectomy: status of kidney donors 10 to 20 years postoperatively. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincenti F, Amend WJ, Kaysen G, Feduska N, Birnbaum J, Duca R, et al. Long term Renal Function in Kidney Donors: Sustained Compensatory Hyperfiltration With No Adverse Effects1. Transplantation. 1983;36(6):626–629. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198336060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iglesias-Marquez R, Calderon S, Santiago-Delpí E, Rive-Mora E, Gonzalez-Caraballo Z, Morales-Otero L, editors. Transplantation proceedings. Elsevier; 2001. The health of living kidney donors 20 years after donation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saran R, Marshall S, Madsen R, Keavey P, Tapson J. Long-term follow-up of kidney donors: a longitudinal study. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 1997;12(8):1615–1621. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.8.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Najarian JS, McHugh L, Matas A, Chavers B. 20 years or more of follow-up of living kidney donors. The Lancet. 1992;340(8823):807–810. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldfarb DA, Matin SF, Braun WE, Schreiber MJ, Mastroianni B, Papajcik D, et al. Renal outcome 25 years after donor nephrectomy. The Journal of urology. 2001;166(6):2043–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim HN, Foley R, Tan L, Rogers T, Bailey RF, Guo H, et al. Long-term consequences of kidney donation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(5):459–469. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fehrman-Ekholm I, Nordén G, Lennerling A, Rizell M, Mjörnstedt L, Wramner L, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease among live kidney donors. Transplantation. 2006;82(12):1646–1648. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000250728.73268.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wafa EW, Refaie AF, Abbas TM, Fouda MA, Sheashaa HA, Mostafa A. End-stage renal disease among living-kidney donors: single-center experience. Exp Clin Transplant. 2011;9(1):14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Waterman AD, Dew MA, Davis CL, McCabe M, Wainright JL, Forland CL, et al. Living-donor follow-up attitudes and practices in US kidney and liver donor programs. Transplantation. 2013;95(6):883–888. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31828279fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Response to Solicitation on Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Living Donor Guidelines. Sect. 2006;116 [Google Scholar]

- 35.OPTN. Policy 18 Living Donor Data Submission Requirements. 2016 Jan 21;:210. ed2016. [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare Provider Reimbursement Manual. Organ Donation and Transplant Reimbursement. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louis TA, Zeger SL. Effective communication of standard errors and confidence intervals. Biostatistics. 2009;10(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Buuren S, Brand JP, Groothuis-Oudshoorn C, Rubin DB. Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation. Journal of statistical computation and simulation. 2006;76(12):1049–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leichtman A, Abecassis M, Barr M, Charlton M, Cohen D, Confer D, et al. Living kidney donor follow-up: state-of-the-art and future directions, conference summary and recommendations. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(12):2561–2568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Karp SJ, Johnson SR, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. Practices and barriers in long-term living kidney donor follow-up: a survey of US transplant centers. Transplantation. 2009;88(7):855–860. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b6dfb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulkarni S, Thiessen C, Formica R, Schilsky M, Mulligan D, D’Aquila R. The Long-Term Follow-up and Support for Living Organ Donors: A Center-Based Initiative Founded on Developing a Community of Living Donors. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(12):3385–3391. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keshvani N, Feurer I, Rumbaugh E, Dreher A, Zavala E, Stanley M, et al. Evaluating the Impact of Performance Improvement Initiatives on Transplant Center Reporting Compliance and Patient Follow-Up After Living Kidney Donation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(8):2126–2135. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Change in Complete and Timely 6-month LDF Form Submission Associated with Post-Policy Implementation (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S2: Change in Complete and Timely 1-year LDF Form Submission Associated with Post-Policy Implementation (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S3: Change in Complete and Timely 2-year LDF Form Submission Associated with Post-Policy Implementation (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S4: Marginal Change Post-Policy Implementation Associated with Complete and Timely 6-month LDF Form Submission (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S5: Marginal Change Post-Policy Implementation Associated with Complete and Timely 1-year LDF Form Submission (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S6: Marginal Change Post-Policy Implementation Associated with Complete and Timely 2-year LDF Form Submission (January 2010 – June 2015)

Table S7: Characteristics Associated with in Incomplete and Non-timely 6-month LDF form submission after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015)

Table S8: Characteristics Associated with in Incomplete and Non-timely 1-year LDF form submission after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015)

Table S9: Characteristics Associated with in Incomplete and Non-timely 2-year LDF form submission after the implementation of the OPTN/UNOS LDF Policy (February 2013 – June 2015)

Figure S1: Timeliness of LDF form submissions for donations January 2010 – June 2015