Abstract

Background: Since the initial appearance in the 1980s, Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) have increased in prevalence and emerged as a major antimicrobial-resistant pathogen. The source of these antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the developed world is an area of active investigation.

Methods: A standard internet search was conducted with a focus on the epidemiology and potential sources of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the developed world.

Results: The last decade has witnessed several major changes in the epidemiology of these bacteria: replacement of TEM and SHV-type ESBLs by CTX-M-family ESBLs, emergence of Escherichia coli ST131 as a prevalent vehicle of ESBL, and spread of ESBL-producing E. coli in the community. The most studied potential sources of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in humans in the community include food and companion animals, the environment and person-to-person transmission, though definitive links are yet to be established. Evidence is emerging that international travel may serve as a major source of introduction of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae into the developed world.

Conclusions: ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae has become a major multidrug-resistant pathogen in the last two decades, especially in the community settings. The multifactorial nature of its expansion poses a major challenge in the efforts to control them.

Keywords: Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase, epidemiology, source

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance constitutes one of the greatest challenges in modern medicine. For the treatment of infections caused by Gram-negative pathogens, the most commonly used classes of antimicrobial agents include fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations thanks to their track records of efficacy, safety and availability in both oral and parenteral formulations. Resistance to these agents would compromise the efficacy of empiric treatment of suspected Gram-negative infections and limit the therapeutic options for their definitive treatment as well.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) are β-lactamases that can hydrolyze penicillins and cephalosporins. Therefore, enteric Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae become resistant to these classes of β-lactam agents when they acquire an ESBL gene and produce the enzyme. ESBLs are pervasive worldwide, with over 1.5 billion people colonized with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae by one estimate.1 The vast majority of this burden falls on the developing countries, but the prevalence of ESBL-producing organisms is also on the rise in the developed countries. In this review, we will discuss the historic background of ESBL, then summarize the current knowledge on the epidemiology and potential sources of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the developed world, defined as North America, Europe, Oceania and parts of East Asia for the purpose of the review.

Classic ESBLs

ESBLs are defined as β-lactamases that are capable of hydrolyzing one or more oxyimino-β-lactams, such as cefotaxime, ceftazidime and aztreonam, at a rate generally >10% of that of benzylpenicillin.2 In the clinical microbiology laboratory, production of an ESBL by gram-negative bacteria is defined by (i) reduced susceptibility to one or more of the following agents (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefpodoxime or aztreonam), and (ii) potentiation of the activity of these agents in the presence of clavulanic acid, which is a β-lactamase inhibitor and clinically available as a component of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid.

It had been known for decades that most Klebsiella pneumoniae strains produced SHV-type non-ESBL β-lactamase, and some Escherichia coli strains produced TEM-type non-ESBL β-lactamase.3 These ‘classic’ enzymes such as SHV-1 and TEM-1 can hydrolyze ampicillin, but cannot not hydrolyze oxyimino-cephalosporins including ceftriaxone, cefotaxime and ceftazidime, which were specifically designed to resist hydrolysis by these enzymes. However, these non-ESBL β-lactamases evolved into ESBLs in the 1980s by acquiring specific amino acid substitutions that altered the substrate specificity to allow for hydrolysis of oxyimino-cephalosporins, thus conferring the bacteria with resistance to these agents.4 These TEM- and SHV-type ESBLs were typically encoded on transferable plasmids, and primarily found in E. coli and K. pneumoniae, but also in other gram-negative bacteria. In the 1990s, outbreaks of ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae were reported from U.S. hospital and nursing homes.5,6 These strains produced TEM- and SHV-type ESBLs and were resistant to oxyimino-cephalosporins, and cross-resistance to other classes of agents (e.g. gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) was common. Today, SHV-type ESBLs account for just over 10% of ESBLs, mostly found in K. pneumoniae, whereas TEM-type ESBLs have become uncommon in the U.S.7

CTX-M-Group ESBLs

CTX-M-group β-lactamases are a group of ESBLs that are distinct from TEM and SHV ESBLs. As a new family, CTX-M ESBLs were first reported in 1989 in Germany as CTX-M-1 (for cefotaximase-Munich).8 These enzymes were increasingly reported in the 1990s and, by early 2000s, surpassed TEM and SHV ESBLs as the most frequently identified group of ESBLs. Six groups of CTX-M ESBLs have been recognized: CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2, CTX-M-8, CTX-M-9, CTX-M-25 and KLUC, with each group differing by ≥10% in amino acid sequence identity, and there are numerous minor variants within the groups.9 Nonetheless, they share two common attributes: (i) the bla genes encoding these enzymes very likely originated from the chromosome of various species of the genus Kluyvera, which belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae but rarely causes human infections, and (ii) these ESBLs preferentially hydrolyze cefotaxime over ceftazidime, which is the opposite of TEM and SHV ESBLs. Interestingly, Kluyvera spp. are usually susceptible to cephalosporins despite the possession of chromosomal CTX-M-group genes. These blaCTX-M genes have been captured by mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as ISEcp1 or ISCR1 and mobilized from the Kluyvera genomes to plasmids in E. coli. Incidentally, some of these MGEs provide active promoter sequences that allow for increased expression of blaCTX-M, thereby conferring clinically relevant level of cephalosporin resistance in E. coli.10

CTX-M-group ESBLs are now by far the most common ESBLs globally, both in the developing and developed worlds, and are found on various plasmid incompatibility groups, but sometimes also integrated into the chromosome.9 They are produced by species across the family Enterobacteriaceae, with E. coli being the most common host, followed by K. pneumoniae. The most common CTX-M ESBLs found in humans worldwide are CTX-M-15 which belongs to the CTX-M-1 group, followed by CTX-M-14 belonging to the CTX-M-9 group.9 In animals, on the other hand, CTX-M-1, which is the canonical enzyme in the CTX-M-1 group, appears to predominate.11 The other CTX-M groups are more geographically limited, with the CTX-M-2 group commonly reported from South America and Japan, the CTX-M-8 group from South America and the CTX-M-25 group from Israel.9

Besides the TEM, SHV and CTX-M-group ESBLs, some other groups of ESBLs are sporadically identified, but they remain relatively rare and are not discussed further (e.g. GES, PER and VEB-group ESBLs).8

Emergence of CTX-M-Producing E. coli ST131

While strains belonging to various clonal lineages of E. coli, K. pneumoniae and other species of Enterobacteriaceae can produce ESBLs, there is a particularly strong association between E. coli sequence type (ST) 131 and production of CTX-M-group ESBLs.12E. coli ST131 was initially recognized as a common clonal lineage producing CTX-M-15 from several countries in Europe, Asia and North America, around the time when introduction of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) enabled direct molecular epidemiological comparison of strains studied in laboratories from different countries.13,14 Further work by Johnson and colleagues as well as Beaston and coworkers led to the identification of a sub-lineage within ST131, termed H30 or clade C, as the core clone which is resistant to fluoroquinolones and driving the global expansion of CTX-M-producing E. coli in both healthcare and community settings.15,16 It is now understood that E. coli ST131 has evolved over many decades, and propagated more recently when it acquired fluoroquinolone resistance in the 1980s and subsequently also blaCTX-M-15.17 More recently, E. coli ST131 H30 has been associated with CTX-M-group ESBLs other than CTX-M-15, highlighting the dynamic and ongoing evolution of this multidrug-resistant E. coli lineage.18E. coli ST131 is predominant in many countries across the developed world, is associated with multidrug resistance and virulence, and has the ability to readily colonize and transmit among human hosts. Therefore it is considered the most significant high-risk clone among ESBL-producing E. coli.19

Burden of ESBL-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in the Developed World

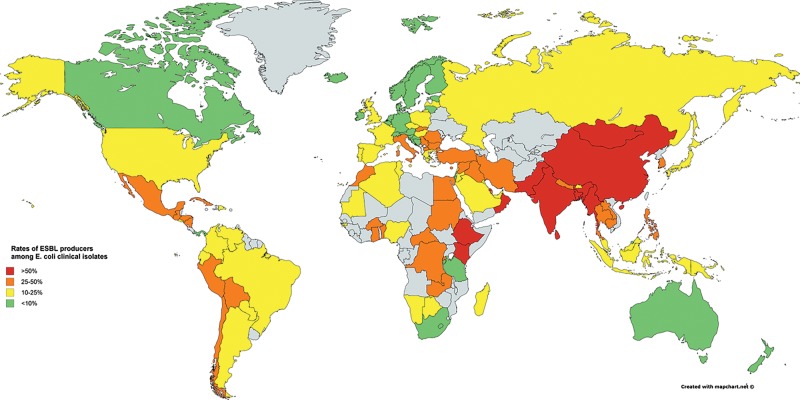

Rates of ESBL production have steadily increased over the last decade for both E. coli and K. pneumoniae in the developed world (Figure 1). The rates of ESBL producers among E. coli urinary strains at U.S. hospitals increased from 7.8% in 2010 to 18.3% in 2014, but this was as high as 27.7% for strains representing hospital-acquired infection in 2014, the majority of which produced CTX-M-15.20 Co-resistance to non-β-lactam agents was also common, with fluoroquinolone susceptibility generally below 30%. For K. pneumoniae, 16.3% of clinical strains collected from hospitals across U.S. between 2011 and 2013 were ESBL producers, the majority of which produced CTX-M-group ESBLs.21 This was in contrast to a different but similarly structured surveillance study that reported only 2.5 to 3.4% of K. pneumoniae strains collected between 1997 and 2000 to demonstrate ESBL phenotypes.22

Figure 1.

Estimated rates of ESBL producers among E. coli clinical isolates. Most of the data were adopted from ‘Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014’ published by the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en/). Grey indicates countries with insufficient data

In Europe, the rates of ESBL producers differ significantly for both E. coli and K. pneumoniae depending on the regions, with very low rates observed in Northern European countries and much higher rates seen in Eastern and Southern European countries.23,24 Less than 10% of E. coli and K. pneumoniae produce ESBL in Canada, but the rates appear to be increasing.25 In Japan, the rates of ESBL producers are around 30% in E. coli and 10% in K. pneumoniae when using the rates of cefotaxime resistance as surrogates.26 The rates are lower in Australia and New Zealand, ranging between 10 and 15% for these species.27

The ESBL production rates are much lower for outpatients who mostly present with E. coli community-associated strains. Among female outpatients in the U.S. presenting with E. coli urinary tract infection for example, ceftriaxone resistance rates were 3.3% for children, 4.5% for adults age ≤64 year old and 9.5% for adults age ≥65 years old in 2012.28

Among children, the overall prevalence of ESBL production among Enterobacteriaceae increased from 0.26% in 1999–2001 to 0.92% in 2010–2011 at U.S. hospitals.29 The latter prevalence, when broken down into the healthcare setting, ranged from 0.6% among outpatients to 7.3% among ICU patients. The majority of the strains were E. coli reflecting the most common causative species of infections among children. Also, non-susceptibility (resistance or intermediate resistance) to non-β-lactam agents was common, ranging from 28.8% to nitrofurantoin to 66.1% to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

In addition to hospitalized and community-dwelling patients, another population that merits attention is residents of long-term care facilities (LTCFs). While data remain limited, some recent studies from Europe report high rates of rectal colonization with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae among residents of LTCFs,30,31 and this population may also constitute a significant healthcare-associated reservoir of E. coli ST131.32,33

Diarrheal illness due to ESBL-producing E. coli remains rare in the developed world and is usually ascribed to recent overseas travel,34 but association of blaCTX-M-14 with enteroaggregative E. coli ST131 has been suggested in a survey from Japan.35

Spread of ESBLs in the Community

In the first decade since the emergence of ESBLs, ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae was considered a healthcare-associated problem, as outbreaks of infections by these organisms were occurring in hospitals or other health care facilities such as nursing homes.36 However, reports on ESBL-producing E. coli infections occurring among patients without previous exposure to health care (such as recent hospitalization, attendance at haemodialysis clinics or receipt of home care) started to appear at the turn of the century.37 Indeed, this spread and abundance of ESBL-producing E. coli in the community settings is one of the defining features of the epidemiology of ESBLs in the developed world in the 21st century.

The first major evidence of this epidemiological shift was presented by Rodríguez-Baño and colleagues, which demonstrated that nearly half of ESBL-producing E. coli infection cases observed at a hospital in Seville, Spain between 2001 and 2002 represented community-onset infections.33 The risk factors for ESBL production included diabetes mellitus, recent use of fluoroquinolones, and hospital admission within the preceding year. CTX-M was the most predominant ESBL type, followed by TEM and SHV. Similar observations were made around the same time in the United Kingdom,38 Italy39 and other countries, all pointing to the emergence of community-associated infections due to CTX-M-producing E. coli. This phenomenon was later observed in the U.S. as well, in North Carolina then across the continental U.S.40,41 In the latter study, the majority were ST131 and carried blaCTX-M-15, demonstrating that E. coli ST131 is a driving force for the spread of ESBL into the community,40 in addition to hospitals and nursing homes which had been and continue to be their other major ecological niche in humans.32

Potential Sources of ESBLs in the Developed World

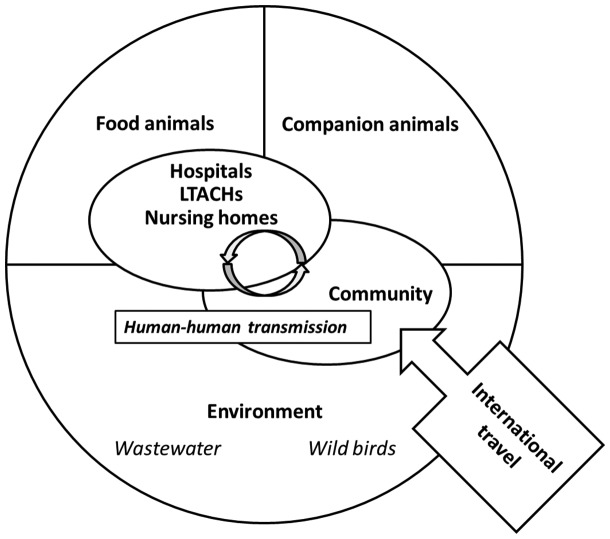

Intestinal colonization typically precedes the onset of infection by Gram-negative bacteria including ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae.42 The overall annual increase in the prevalence of fecal carriage was estimated to be approximately 5%, which is consistent with the steady rise in the incidence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections.43 These observations have motivated numerous investigations aimed at identifying the source of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae leading to intestinal colonization with these organisms. Broadly speaking, five sources have been postulated as contributing to this rising prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonization in the developed world (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual scheme of the ecology of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriacae in the developed world

Food Animals

More than three quarters of all antimicrobial use is in livestock and not humans, administered for treatment of infection (in particular respiratory tract infection and diarrheal disease), prevention of infection and sometimes for the purpose of growth promotion.44 ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, in particular E. coli and non-typhoidal Salmonella, are commonly identified in food-producing animals in Europe. For example, over 90% of retail poultry meat in southern Spain contained ESBL-producing E. coli in 2010, up from just over 60% in 2007.45 In the Netherlands, a survey of retail packaged meat products conducted in 2009 showed that almost 80% of chicken samples contained ESBL producers, most of which were E. coli, whereas the rates were much lower in beef and pork.46 CTX-M-1 was the most common ESBL in both chicken and human isolates. Furthermore, common STs of ESBL-producing E. coli were shared between isolates from meat and stool of patients hospitalized in the same region, with a notable exception of E. coli ST131 which was found only in humans, leading the investigators to conclude that chicken was a plausible source of ESBL genes in humans but perhaps not of E. coli ST131. Similar findings were reported by another group in the Netherlands.47 However, when some of these human and poultry strains were re-examined using whole genome sequencing, the strains that were previously considered related between animals and humans had numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) suggesting their separate origins.48 Instead, reconstruction of plasmid sequences showed that a nearly identical plasmid backbone, in this instance of the IncI1 of group, was found in multiple human and poultry strains, suggesting that certain plasmids may serve as carriers of ESBL genes from livestock animals to humans. This notion was further supported by a recent European study where IncI1 plasmids harboring blaCTX-M-1 were commonly identified in animal isolates and were also seen in human E. coli isolates across various STs.49

Data are much scarcer in the United States, but the rates of contamination by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae appear to be much lower than in Europe. In a survey of retail chicken, turkey, pork and ground beef conducted in Pennsylvania between 2006 and 2007, only one of the chicken samples contained ESBL-producing E. coli.50 More recently, CTX-M-producing E. coli was recovered from 7% of retail meat products purchased in three Midwestern states in 2012.51 However, over 50% of them contained E. coli producing CMY-2, an acquired AmpC-type β-lactamase that confers cephalosporin resistance but is not an ESBL due to the lack of inhibition of its activity by commonly used β-lactamase inhibitors.

Companion Animals

Companion animals are increasingly drawing attention as a potential source, or vector of ESBL-producing Enterobaceriaceae because of their physical proximity and frequent close contacts with their owners. In a surveillance study of diseased dogs and cats across Europe, 1.6% carried ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in stool, most of which harbored blaCTX-M, but included only 2 E. coli ST131 isolates, suggesting that companion animals may be a source of ESBL genes in general but are unlikely to be a major source of this epidemic clone.52 The ESBL carriage rates were much higher in the Netherlands, with approximately a quarter of dogs screened carrying ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in their stool.53 Furthermore, when dogs were screened longitudinally over 6 months, again in the Netherlands, over 80% of the dogs carried an ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae strain at some point, suggesting that many dog owners are intermittently exposed to these bacteria. ESBL-producing E. coli from cats and dogs belonged to various STs, but carried blaCTX-M genes on plasmids that were common in humans such as IncF and IncI1.54 In the U.S., 3.1% of diseased dogs and cats carried ESBL-producing E. coli, with the predominance of blaCTX-M-15 harbored on IncF and IncI1 plasmids.55 Therefore, as with food animals, companion animals may serve as a source of ESBL-encoding plasmids to humans.

Humans

Person-to-person transmission, especially within household, has also been postulated as a means of spread of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. When family members of patients who had community-acquired infections due to ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae were screened for fecal carriage in Spain, 9 of 54 were colonized in the gastrointestinal tract, and 6 of them were colonized with a strain that had identical banding patterns by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, strongly indicating transmission within households.56 In the Netherlands, when 84 household members of 74 patients who had ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infection were followed for 18 months with periodic fecal surveillance, more than half of them had ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae at some point.57 An extensive household outbreak of CTX-M-15-producing E. coli ST131 has also been reported from the U.S., where 2 siblings had urinary tract infection and 4 other family members were colonized by the same strain.58 The limited evidence suggests that, once introduced to households, person-to-person transmission can be a significant means of the spread of ESBL-producing bacteria in the community.

Environment

Environmental contamination with ESBL-producing Enterob acteriaceae is increasingly reported, more in the developing world but also in the developed world. Of particular interest is wastewater, which captures consequence of human activities and has the potential for extensive environmental contamination. In a longitudinal survey of various wastewater sources in France, ESBL-producing E. coli could be recovered from most samples, mostly harboring blaCTX-M, at significantly higher counts in hospital wastewater than community wastewater.59 Indeed, proportions of ESBL producers among E. coli are consistently higher in hospital effluents than community effluents, likely reflecting the higher rates of ESBL carriage among inpatients over community dwellers and also the difference in the levels of selective pressure from residual antibiotics in wastewater.60 The STs found in wastewater are also reflective of those common in humans. For example, E. coli ST131 carrying blaCTX-M-15 was the predominant clone among ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae recovered from the outflow of a wastewater treatment plant in Czech Republic.61

Another entity that has been investigated as a potential environmental source of ESBL producers is wildlife, especially birds. In a survey of carcasses of wild birds in the Netherlands, mostly representing aquatic species such as gulls, waterfowl and waders, 12.3% of the fecal samples grew ESBL-producing E. coli, representing various ESBL genes including blaCTX-M, blaSHV and blaTEM.62 In another study of wild birds, stool of nestlings was collected in Germany and Mongolia. ESBL-producing E. coli was identified in 13.8% and 10.8% of German and Mongolian nestlings of raptors, respectively. Interestingly, the dominant ESBL gene was blaCTX-M-1 in Germany and blaCTX-M-9 in Mongolia, which likely reflected the local epidemiology in humans.63 Even a higher carriage rate has been reported in gulls in Spain (74.8%) in a study across Europe, which was predominated by E. coli carrying blaCTX-M-1 or blaCTX-M-14.64 While the overall contribution is difficult to quantify, birds that can freely migrate between urban and agricultural lands may play a role in the spread of ESBL-producing bacteria across geographic areas and ecological niches.

International Travel

Over 1 billion people cross international borders for tourism alone every year, and the number is expected to grow. In a meta-analysis of studies reporting fecal colonization of healthy individuals with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, the pooled estimated prevalence of colonization was high across the developing regions: 46% in the West Pacific, 22% in Southeast Asia and 22% in Africa. On the other hand, the colonization prevalence was much lower yet still significant in the developed regions: 4% in Europe and 2% in the Americas.43 The disparity in the prevalence of carriage of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the developing and developed worlds and commoditization of international travel create an opportunity for these organisms to be transported by colonized travelers. The first study to support this hypothesis came from Canada, in which risk factors for community-associated ESBL-producing E. coli infection were investigated.65 In this study, history of overseas travel was a strong risk factor for such infection (odds ratio [OR], 5.7). In particular, history of travel to India had an extraordinary OR of 145.6. A similarly designed study from the U.S. also singled out travel to India in the past year as a strong risk factor for community-onset ESBL-producing E. coli infection (OR, 14.4).66 The actual risks of ESBL colonization during travel to the developing world have been estimated in several studies using pre-travel and post-travel fecal screening. The common theme with these studies is the high colonization rates upon returning from India, or more broadly South Asia, ranging up to 70% of returning travelers.67–70 Other commonly identified risk factors included traveler’s diarrhea, use of antibiotics and length of the trip. Medical tourism, where patients from the developed countries travel to countries with lower medical costs to receive health care such as elective surgeries, may also play a role in the importation of multidrug-resistant bacteria including ESBL-producing ones.71 However, prolonged carriage after returning to the developed world may be uncommon, with most travelers losing carriage by 3 months after return.72,73 Nonetheless, the magnitude of the acquisition risk and the number of travelers make travel to developing countries a highly plausible source of ESBL acquisition in the developed countries.

Conclusions

ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae have increased in prevalence and emerged as a major antimicrobial-resistant pathogen in the developed world. This increase has coincided with a shift in the ESBL types (from TEM and SHV to CTX-M group) and spread of ESBL-producing E. coli into the community. Of particular epidemiological concern is dissemination of ESBL-producing E. coli ST131, which is characterized by high rates of co-resistance to fluoroquinolones and other classes of agents. The rapid dissemination of ESBL-producing organisms is likely multifactorial, but potential contributing sources include animals (both food and companion), the environment, importation through travel and direct transmission within households and the community. The steady and continued increase of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections and the associated antimicrobial use has a potential to further select for even more resistant pathogens such as carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01AI104895, R21AI123747 to Y. D., R01AI072219, R01AI063517, R01AI100560 to R. A. B.), the Department of Veterans Affairs Research and Development (grant number I01BX001974 [to R. A. B.]), and the VISN 10 Geriatrics Research, Education and Clinical Center (to R. A. B.).

Conflicts of interest: Y.D. has served on advisor boards for Shionogi, Meiji, Tetraphase, Achaogen, Allergan, Curetis, received speaking fee from Merck, and received research funding from Merck and The Medicines Company for studies unrelated to this work. All other authors: no potential.

References

- 1. Woerther PL, Burdet C, Chachaty E, Andremont A.. Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26:744–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bush K, Jacoby GA.. Updated functional classification of β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:969–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paterson DL, Bonomo RA.. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005; 18:657–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kliebe C, Nies BA, Meyer JF, Tolxdorff-Neutzling RM, Wiedemann B.. Evolution of plasmid-coded resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1985; 28:302–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiener J, Quinn JP, Bradford PA. et al. Multiple antibiotic-resistant Klebsiella and Escherichia coli in nursing homes. JAMA 1999; 281:517–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Quale JM, Landman D, Bradford PA. et al. Molecular epidemiology of a citywide outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:834–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castanheira M, Mendes RE, Jones RN, Sader HS.. Changing of the frequencies of β-lactamase genes among Enterobacteriaceae in US hospitals (2012-2014): activity of ceftazidime-avibactam tested against β-lactamase-producing Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:4770–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bauernfeind A, Grimm H, Schweighart S.. A new plasmidic cefotaximase in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Infection 1990; 18:294–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. D'Andrea MM, Arena F, Pallecchi L, Rossolini GM.. CTX-M-type β-lactamases: a successful story of antibiotic resistance. Int J Med Microbiol 2013; 303:305–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poirel L, Lartigue MF, Decousser JW, Nordmann P.. ISEcp1B-mediated transposition of blaCTX-M in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:447–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seiffert SN, Hilty M, Perreten V, Endimiani A.. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative organisms in livestock: an emerging problem for human health? Drug Resist Updat 2013; 16:22–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banerjee R, Johnson JR.. A new clone sweeps clean: the enigmatic emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4997–5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V. et al. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61:273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coque TM, Novais A, Carattoli A. et al. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14:195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B. et al. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:919–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Stanton-Cook M. et al. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:5694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Pankhurst L . et al. Modernizing medical microbiology informatics G. evolutionary history of the global emergence of the Escherichia coli epidemic clone ST131. mBio 2016; 7:e02162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matsumura Y, Johnson JR, Yamamoto M, Kyoto-Shiga Clinical Microbiology Study G, Kyoto-Shiga Clinical Microbiology Study G et al. CTX-M-27- and CTX-M-14-producing, ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli of the H30 subclonal group within ST131 drive a Japanese regional ESBL epidemic. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:1639–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mathers AJ, Peirano G, Pitout JD.. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015; 28:565–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lob SH, Nicolle LE, Hoban DJ, Kazmierczak KM, Badal RE, Sahm DF.. Susceptibility patterns and ESBL rates of Escherichia coli from urinary tract infections in Canada and the United States, SMART 2010-2014. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 85:459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castanheira M, Mills JC, Costello SE, Jones RN, Sader HS.. Ceftazidime-avibactam activity tested against Enterobacteriaceae isolates from U.S. hospitals (2011 to 2013) and characterization of β-lactamase-producing strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:3509–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones RN, Biedenbach DJ, Gales AC.. Sustained activity and spectrum of selected extended-spectrum β-lactams (carbapenems and cefepime) against Enterobacter spp. and ESBL-producing Klebsiella spp.: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (USA, 1997-2000). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2003; 21:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jones RN, Flonta M, Gurler N, Cepparulo M, Mendes RE, Castanheira M.. Resistance surveillance program report for selected European nations (2011). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 78:429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2014. 2015. (http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/antimicrobial-resistance-europe-2014.pdf.)

- 25. Denisuik AJ, Lagace-Wiens PR, Pitout JD. et al. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-, AmpC β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from Canadian hospitals over a 5 year period: CANWARD 2007-11. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68 Suppl 1:i57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance. Annual open report 2014 (all facilities). 2016. (http://www.nih-janis.jp/english/report/open_report/2014/3/1/ken_Open_Report_Eng_201400_clsi2012.pdf.)

- 27. Mendes RE, Mendoza M, Banga Singh KK. et al. Regional resistance surveillance program results for 12 Asia-Pacific nations (2011). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57:5721–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanchez GV, Babiker A, Master RN, Luu T, Mathur A, Bordon J.. Antibiotic resistance among urinary isolates from female outpatients in the United States in 2003 and 2012. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:2680–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Logan LK, Braykov NP, Weinstein RA, Laxminarayan R.. Program CDCEP. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in children: Trends in the United States, 1999-2011. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014; 3:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hogardt M, Proba P, Mischler D, Cuny C, Kempf VA, Heudorf U.. Current prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms in long-term care facilities in the Rhine-Main district, Germany, 2013. Euro Surveill 2015; 20(26):21171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ludden C, Cormican M, Vellinga A, Johnson JR, Austin B, Morris D.. Colonisation with ESBL-producing and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a long-term care facility over one year. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:168.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Banerjee R, Johnston B, Lohse C, Porter SB, Clabots C, Johnson JR.. Escherichia coli sequence type 131 is a dominant, antimicrobial-resistant clonal group associated with healthcare and elderly hosts. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34:361–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodriguez-Bano J, Navarro MD, Romero L. et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in nonhospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:1089–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Reuland EA, Sonder GJ, Stolte I. et al. Travel to Asia and traveller's diarrhoea with antibiotic treatment are independent risk factors for acquiring ciprofloxacin-resistant and extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae–a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 71:1076–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Imuta N, Ooka T, Seto K. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) isolated in Japan revealed the emergence of CTX-M-14-producing EAEC O25:H4 clones related to ST131. J Clin Microbiol 2016; 54:2128–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jacoby GA. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases and other enzymes providing resistance to oxyimino-β-lactams. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1997; 11:875–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arpin C, Coulange L, Dubois V. et al. Extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae strains in various types of private health care centers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:3440–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Woodford N, Ward ME, Kaufmann ME. et al. Community and hospital spread of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004; 54:735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brigante G, Luzzaro F, Perilli M. et al. Evolution of CTX-M-type β-lactamases in isolates of Escherichia coli infecting hospital and community patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005; 25:157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Doi Y, Park YS, Rivera JI. et al. Community-associated extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56:641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Freeman JT, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ.. Emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in community hospitals throughout North Carolina: a harbinger of a wider problem in the United States? Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:e30–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Donskey CJ. Antibiotic regimens and intestinal colonization with antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43 Suppl 2:S62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvanitis M, Grigoras C, Mylonakis E.. Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:310–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hollis A, Ahmed Z.. Preserving antibiotics, rationally. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:2474–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Egea P, Lopez-Cerero L, Torres E. et al. Increased raw poultry meat colonization by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the south of Spain. Int J Food Microbiol 2012; 159:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Overdevest I, Willemsen I, Rijnsburger M. et al. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes of Escherichia coli in chicken meat and humans, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1216–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leverstein-van Hall MA, Dierikx CM, Cohen Stuart J. et al. Dutch patients, retail chicken meat and poultry share the same ESBL genes, plasmids and strains. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:873–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de Been M, Lanza VF, de Toro M. et al. Dissemination of cephalosporin resistance genes between Escherichia coli strains from farm animals and humans by specific plasmid lineages. PLoS Genet 2014; 10:e1004776.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Day MJ, Rodriguez I, van Essen-Zandbergen A. et al. Diversity of STs, plasmids and ESBL genes among Escherichia coli from humans, animals and food in Germany, the Netherlands and the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016; 71:1178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Doi Y, Paterson DL, Egea P. et al. Extended-spectrum and CMY-type β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in clinical samples and retail meat from Pittsburgh, USA and Seville, Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010; 16:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mollenkopf DF, Cenera JK, Bryant EM. et al. Organic or antibiotic-free labeling does not impact the recovery of enteric pathogens and antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli from fresh retail chicken. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2014; 11:920–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bogaerts P, Huang TD, Bouchahrouf W. et al. Characterization of ESBL- and AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae from diseased companion animals in Europe. Microb Drug Resist 2015; 21:643–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hordijk J, Schoormans A, Kwakernaak M. et al. High prevalence of fecal carriage of extended spectrum β-lactamase/AmpC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in cats and dogs. Front Microbiol 2013; 4:242.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dahmen S, Haenni M, Chatre P, Madec JY.. Characterization of blaCTX-M IncFII plasmids and clones of Escherichia coli from pets in France. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68:2797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shaheen BW, Nayak R, Foley SL. et al. Molecular characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in clinical Escherichia coli isolates from companion animals in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:5666–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Valverde A, Grill F, Coque TM. et al. High rate of intestinal colonization with extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing organisms in household contacts of infected community patients. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46:2796–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haverkate MR, Platteel TN, Fluit AC. et al. Quantifying within-household transmission of ESBL-producing bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 23:46.e1–46.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Madigan T, Johnson JR, Clabots C. et al. Extensive household outbreak of urinary tract infection and intestinal colonization due to extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:e5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brechet C, Plantin J, Sauget M. et al. Wastewater treatment plants release large amounts of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli into the environment. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:1658–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hocquet D, Muller A, Bertrand X.. What happens in hospitals does not stay in hospitals: antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospital wastewater systems. J Hosp Infect 2016; 93:395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Dolejska M, Frolkova P, Florek M. et al. CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli clone B2-O25b-ST131 and Klebsiella spp. isolates in municipal wastewater treatment plant effluents. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66:2784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Veldman K, van Tulden P, Kant A, Testerink J, Mevius D.. Characteristics of cefotaxime-resistant Escherichia coli from wild birds in the Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 2013; 79:7556–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Guenther S, Aschenbrenner K, Stamm I. et al. Comparable high rates of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in birds of prey from Germany and Mongolia. PLoS One 2012; 7:e53039.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Stedt J, Bonnedahl J, Hernandez J. et al. Carriage of CTX-M type extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in gulls across Europe. Acta Vet Scand 2015; 57:74.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Laupland KB, Church DL, Vidakovich J, Mucenski M, Pitout JD.. Community-onset extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli: importance of international travel. J Infect 2008; 57:441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Banerjee R, Strahilevitz J, Johnson JR. et al. Predictors and molecular epidemiology of community-onset extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection in a Midwestern community. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34:947–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kantele A, Laaveri T, Mero S. et al. Antimicrobials increase travelers' risk of colonization by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:837–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ostholm-Balkhed A, Tarnberg M, Nilsson M. et al. Travel-associated faecal colonization with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae: incidence and risk factors. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68:2144–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yaita K, Aoki K, Suzuki T. et al. Epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli in the stools of returning Japanese travelers, and the risk factors for colonization. PLoS One 2014; 9:e98000.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kuenzli E, Jaeger VK, Frei R. et al. High colonization rates of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in Swiss travellers to South Asia- a prospective observational multicentre cohort study looking at epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:528.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chen LH, Wilson ME.. The globalization of healthcare: implications of medical tourism for the infectious disease clinician. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1752–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ruppe E, Armand-Lefevre L, Estellat C. et al. High rate of acquisition but short duration of carriage of multidrug-desistant Enterobacteriaceae after travel to the tropics. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pires J, Kuenzli E, Kasraian S. et al. Polyclonal intestinal colonization with extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae upon traveling to India. Front Microbiol 2016; 7:1069.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]