Abstract

Depression currently affects 350 million people worldwide and 19 million Americans each year. Women are 2.5 times more likely to experience major depression than men, with some women appearing to be at a heightened risk during the menopausal transition. Estrogen signaling has been implicated in the pathophysiology of mood disorders including depression; however, the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, the role of estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes, ERα and ERβ, in the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and serotonin (5-HT) signaling was investigated; two pathways that have been hypothesized to be interrelated in the etiology of depression. The analyses in ERα-/- and ERβ-/- mouse models demonstrated that BDNF was significantly downregulated in ERβ-/- but not ERα-/- mice, and the ERβ-/--mediated effect was brain-region specific. A 40% reduction in BDNF protein expression was found in the hippocampus of ERβ-/- mice; in contrast, the changes in BDNF were at a much smaller magnitude and insignificant in the cortex and hypothalamus. Further analyses in primary hippocampal neurons indicated that ERβ agonism significantly enhanced BDNF/TrkB signaling and the downtream cascades involved in synaptic plasticity. Subsequent study in ERβ mutant rat models demonstrated that disruption of ERβ was associated with a significantly elevated level of 5-HT2A but not 5-HT1A in rat hippocampus, indicating ERβ negatively regulates 5-HT2A. Additional analyses in primary neuronal cultures revealed a significant association between BDNF and 5-HT2A pathways, and the data showed that TrkB activation downregulated 5-HT2A whereas activation of 5-HT2A had no effect on BDNF, suggesting that BDNF/TrkB is an upstream regulator of the 5-HT2A pathway. Collectively, these findings implicate that the disruption in estrogen homeostasis during menopause leads to dysregulation of BDNF–5-HT2A signaling and weakened synaptic plasticity, which together predispose the brain to a vulnerable state for depression. Timely intervention with an ERβ-targeted modulator could potentially attenuate this susceptibility and reduce the risk or ameliorate the clinical manifestation of this brain disorder.

Keywords: Menopausal depression, estrogen receptor β (ERβ), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, hippocampus

1. Introduction

Depression is a chronic, reoccurring neuropsychiatric disease that currently affects 350 million people worldwide including 6.7% of Americans (World Health Organization, 2012). Although significant progress has been made in the development of antidepressants, current treatments yield a therapeutic efficacy in only 60% of depressed patients (Rush et al., 2009) and are associated with several unfavorable side effects (Feighner, 1999; Holm and Markham, 1999). Moreover, the mechanism of action underlying the therapeutic effect of antidepressants is currently unknown. These facts underscore the importance of understanding the mechanistic etiology of depression and developing novel therapeutic methods based on that understanding.

Depression disproportionately affects men and women. Epidemiological data have revealed that women are 2.5 times more likely to experience major depression than men (Weissman et al., 1984), with some women appearing to be at a heighted risk during the menopausal transition (Campbell et al., 2017; Pratt LA, 2014), a period characterized by irregular cycling coupled with fluctuations in gonadal steroid hormone levels. Moreover, several clinical studies have demonstrated significantly reduced depression and mood-related symptomology in menopausal patients undergoing estrogen therapy (ET) when compared to placebo controls (Schmidt et al., 2000; Soares et al., 2001). It has been suggested that estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, act as the primary regulators of ET-mediated antidepressant effects, however, their specific roles remain controversial. On one hand, post-partum rats treated with an ERα agonist demonstrated reduced depressive behavior in multiple tests suggesting a primary regulatory role for ERα (Furuta et al., 2013). In contrast, ovariectomized (OVX) rats treated with an ERβ agonist (Walf et al., 2009; Weiser et al., 2009) exhibited significantly less depressive behavior than rats treated with vehicle or an ERα agonist (Yang et al., 2014); an effect that was absent in ERβ-/- mice (Walf et al., 2009), indicating that ERβ signaling may play a key role in the mechanism of ET in depression. These disparities require further molecular-level investigations.

Serotonin (5-HT) is central to the monoamine hypothesis of depression (Coppen, 1967). Increased 5-HT bioavailability in the synapses and thus increased 5-HT function has been shown to effectively relieve depressive symptoms (Delgado et al., 1990). 5-HT induces its wide range of actions through a myriad of receptors, the expression and function of which has also been heavily studied in an attempt to unravel the pathophysiology of depression. Studies have reported a decrease in the 5-HT1A receptor signaling (Hirvonen et al., 2008) and an increase in the 5-HT2A receptor signaling (Shelton et al., 2009) in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of depressed patients when compared to control subjects, which was reversed in the subjects treated with antidepressants (Celada et al., 2004), implicating the involvement of these receptors in the etiology of depression.

Although 5-HT signaling is highly implicated in depression, contradictory reports (for review see (Hinz et al., 2012)) and the inability of the monoamine hypothesis to explain certain clinical findings such as therapeutic lag (Frazer and Benmansour, 2002) have shifted the research focus towards novel alternative mechanisms of depression (Duman and Monteggia, 2006). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is essential to the more recent and clinically relevant neurotrophic hypothesis of depression. Several clinical and animal studies (Dwivedi et al., 2003; Lippmann et al., 2007) have reported a decrease in the mRNA and protein expression levels of BDNF and TrkB in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of depressed subjects when compared with control subjects, which was reversed by chronic but not acute antidepressant treatment (Xu et al., 2003). In addition, mice heterozygous for a BDNF null allele (BNDF+/-) and overexpressing TrkB transgenic gene were found to be resistant to antidepressants (Saarelainen et al., 2003), indicating that BDNF/TrkB signaling is required for the therapeutic effects of antidepressants. Although behavioral and clinical studies strongly support a connection between depression and BDNF signaling, the short half-life of BDNF in systemic circulation (Sakane and Pardridge, 1997) and its blood-brain barrier (BBB) impermeability (Sakane and Pardridge, 1997) hinders its use as a therapeutic agent.

Both the monoaminergic and neurotrophic hypotheses of depression fall short of providing a viable therapeutic window, thus it is highly possible that the key for understanding and successfully treating depression may be found by examining the interaction of these two divergent signaling pathways. 5-HT signaling has been shown to regulate BDNF/TrkB signaling in the hippocampus (Vaidya et al., 1997). Parallel to these studies, BNDF infusion in the midbrain has been reported to increase 5-HT turnover and promote phenotype and function of serotonergic neurons (Siuciak et al., 1996). Additionally, the Val66Met BDNF mouse model exhibits a compromised selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) response (Yu et al., 2012), while BNDF+/- mice demonstrate reduced 5-HT1A (Hensler et al., 2007) and increased 5-HT2A sensitivity (Trajkovska et al., 2009) in the hippocampus. These observations suggest a possible intertwined interaction of these two different signaling molecules, thus highlighting an important avenue for further investigation.

The goal of this study was to investigate the role of ERs in the regulation of BDNF and 5-HT signaling in the female brain. The analyses in ERα-/- and ERβ-/- animal models demonstrated brain region-specific regulation of BDNF by ERβ but not ERα. Additionally, the data indicate that 5-HT2A and not 5-HT1A is negatively regulated by ERβ. Taken together, these results suggest that ERβ-mediated regulation of BDNF–5-HT2A signaling could play a major role in both the development and intervention of depressive disorders in menopausal women.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

4,4′,4″-(4-Propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl) trisphenol (PPT; ERα agonist), 2,3-bis(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile (DPN; ERβ agonist), 4-[2-Phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl) pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol (PHTPP; ERβ antagonist), 4-Iodo-2,5-dimethoxy-α-methylbenzeneethanamine hydrochloride (DOI; 5-HT2A/2C agonist), 7,8-Dihydroxy-2-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (7,8 DHF; TrkB agonist), and 4-(4-Fluorobenzoyl)-1-(4-phenylbutyl)piperidine oxalate (4F 4PP oxalate; 5-HT2A antagonist) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). Chemicals were dissolved at 10-50 mM in analytically pure ethanol and further diluted in culture medium to the final working concentrations (PPT: 100 nM, DPN: 100 nM, PHTPP: 1 μM, DOI: 3 μM, 7,8 DHF: 10 μM, and 4F 4PP oxalate: 10 μM) immediately prior to use. The sources of other materials are indicated in the experimental methods described below.

2.2. Animal models

The use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kansas and followed NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Embryonic day-18 fetuses derived from time-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were used to obtain primary hippocampal neuronal cultures for in vitro experiments. In vivo experiments were carried out in ERα-/- and ERβ-/- mouse and rat models. ERα-/- and ERβ-/- mouse models (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were created by using a targeting vector containing a neomycin resistance gene driven by the mouse phosphoglycerate kinase promoter to introduce stop codons into exon 2 or exon 3 for ERα-/- and ERβ-/- respectively. The construct was introduced into 129P2/OlaHsd-derived E14TG2a embryonic stem (ES) cells (BK4 subline). Correctly targeted ES cells were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to obtain chimeric animals. These mice were then backcrossed to C57BL/6J for eight generations. The line was then bred to C57BL/6NTac from which homozygotes were generated. The ERβ mutant rats were generated using zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) mediated genome editing to target deletion of exon 3 (Ex 3-/-) and exon 4 (Ex 4-/-) in the ERβ gene (Cameron et al., 1995) and are available at the Rat Resource and Research Center (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO). The Ex 3-/- mutation results in a frameshift and a null mutation, whereas the Ex 4-/- mutation results in a DNA binding deficient ERβ variant protein. Animals (mice at 6 months of age and rats at 6 and 10 months of age) were euthanized via thoracotomy and cortical, hippocampal and hypothalamic brain regions were immediately dissected and flash frozen in dry ice (n=5 for each genotype and age group).

2.3. Primary hippocampal neurons

Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons were prepared from embryonic day-18 fetuses derived from time-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats. Briefly, after dissected from the brains of the rat fetuses, the hippocampi were treated with 0.02% trypsin in Hank's balanced salt solution (137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 0.34 mM Na2HPO4·7H2O, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES) at 37 °C for 5 min and dissociated by repeated passage through a series of fire-polished constricted Pasteur pipettes. Cells were plated at a density of 5×105 on 0.1% polyethylenimine-coated 60 mm petri dishes. Neurons were grown in phenol-red free Neurobasal medium (NBM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with B27, 5 U/ml penicillin, 5 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.5 mM glutaMAX and 25 μM glutamate at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for the first 3 days and NBM without glutamate afterwards. Cultures grown in serum-free NBM yielded approximately 99.5% neurons and 0.5% glial cells.

2.4. Protein extraction

Primary hippocampal neuronal cultures were treated at 5 days in vitro (DIV) with respective chemicals for 4 days unless other duration of treatment is indicated. Following the treatment, cultures were washed with cold PBS (pH 7.2), lysed in cold lysis buffer (N-PER, Thermo Scientific, MA)and then harvested with a cell scraper, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Protein concentrations were determined via BCA Assay (Pierce Biotechnology, IL). For tissue protein extraction, 30 mg of hippocampal, cortical and hypothalamic tissue samples were homogenized using a Bullet Blender 24 Homogenizer (Next Advance, NY) in T-PER (Pierce Biotechnology, IL) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science, IN) and 100 μL 0.5 mm glass beads (Next Advance, NY) at speed 8 for 3 min at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 8 min at 4°C. Supernatants were transferred to new microcentrifuge tubes and protein concentrations were determined via BCA Assay (Pierce Biotechnology, IL).

2.5. Western blot

Equal amounts of total protein (20 μg/lane) were loaded and separated by 10% Glycine SDS-PAGE/Tricine SDS-PAGE. Resolved proteins were transferred to 0.2 μm pore-sized PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, CA) and blocked with 5% Blotting Grade Blocker (BioRad, CA) in TBST (100 mL 10× TBS (200 mM Tris, 1.5 mM NaCl, pH 7.6), 10 mL 10% Tween-20, 890 mL ddH2O) for 1 hr at RT followed by incubation with customized dilutions of primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Following overnight incubation, membranes were washed 3 times for 10 min in TBST at RT, followed by incubation with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000; Pierce) for 1 hr at RT. Blots were again washed 3 times for 10 min in TBST. Bands were visualized using chemiluminescence with an ECL detection kit (BioRad) and scanned using the C-Digit Blot Scanner (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Relative intensities of the immunoreactive bands were quantified using image digitizing software, Image Studio Version 4.0 (LI-COR). Membranes were stripped in 5 mL Restore PLUS Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific) for 8 min at RT and re-probed with the indicated loading control. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-BDNF (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX), rabbit polyclonal anti-TrkB (1:1000; Abcam, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-pTrkB (targeting Y515 phosphorylation site; 1:1000; Bioworld Technology Inc., MN), rabbit polyclonal anti-PSD95 (1:500; Alomone Labs, IL), rabbit monoclonal anti-Synaptophysin (1:1000; Abcam, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-VAMP2 (1:2000; Enzo Life Sciences, NY), rabbit polyclonal anti-5-HT1A (1:1000; Abcam, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-5-HT2A (1:20,000; a generous gift from Dr. Nancy Muma), rabbit polyclonal anti-β Actin (1:3000; Thermo Scientific, MA), and mouse monoclonal anti-β Tubulin (1:3000; Thermo Scientific, MA).

Validation of specificity of BDNF antibody

For BDNF protein expression, densitometry of the mature form of BDNF (mBDNF) was performed. mBDNF has been shown to exist in monomeric form with a molecular mass of 14 kDa (Koo et al., 2013; Yan et al., 1997) and trimeric form with a molecular mass of 42 kDa (Dunham et al., 2009; Spires et al., 2004; Wessels et al., 2015). The antibody used in the study detected both of these forms (Fig. 1a) and the expression level of each form is presented individually.

Figure 1. ERβ, not ERα, knockout downregulates BDNF and TrkB in female mouse hippocampus.

a) Validation of specificity of BDNF antibody. Western blots show both the monomeric (14 kDa) and trimeric (42 kDa) forms of mature BDNF in mouse hippocampal protein lysates. b) BDNF regulation by ERs was examined in three brain regions of ERα-/- and ERβ-/- female mice. Data indicate that: b-c) BDNF is not regulated by either ER in mouse cortex and hypothalamus; d-e) ERβ but not ERα regulates BDNF and TrkB protein expression in mouse hippocampus. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation, n=5. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. For comparisons between two groups, Student's t-test was used; for comparisons involving multiple groups, one-way or two-way ANOVA with Turkey's or Dunnett's post-hoc test were used. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad software Inc., CA). The statistical significance was indicated by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. ERβ, not ERα, knockout downregulates BDNF and TrkB in female mouse hippocampus

Using ERα-/- and ERβ-/- mouse models, the involvement of ERα and ERβ in the regulation of BDNF in different regions of the female brain was examined. Cortical, hypothalamic and hippocampal tissues were harvested from 6-month-old ERα-/- and ERβ-/- female mice (n=5/group) and probed for both monomeric (14 kDa) and trimeric (42 kDa) BDNF immunoreactivity (Figure 1). The data show no significant difference in BDNF expression levels in cortical tissues derived from either ER-/- model indicating that BDNF is not regulated by ER signaling in the mouse cortex (Figure 1b, monomeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 0.4, p=0.6870; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 2.99, p=0.1254). Similarly, no change in BDNF expression was detected in the hypothalamus of ERα-/- and ERβ-/- mice (Figure 1c, monomeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 0.439, p=0.6635; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 1.33, p=0.3320). In contrast, hippocampal BDNF levels were significantly reduced in ERβ-/- mice but not ERα-/- mice (Figure 1d, monomeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 12.76, p=0.0075; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 7.23, p=0.0048). Further analyses demonstrated a 50% decrease in the expression of the BDNF receptor, TrkB, in ERβ-/- but not ERα-/- mice (Figure 1e, F(2,6) = 13.81, p=0.0057). Collectively, these data indicate that ERβ, but not ERα, regulates the BDNF and TrkB expression level in the hippocampus of the female mouse brain.

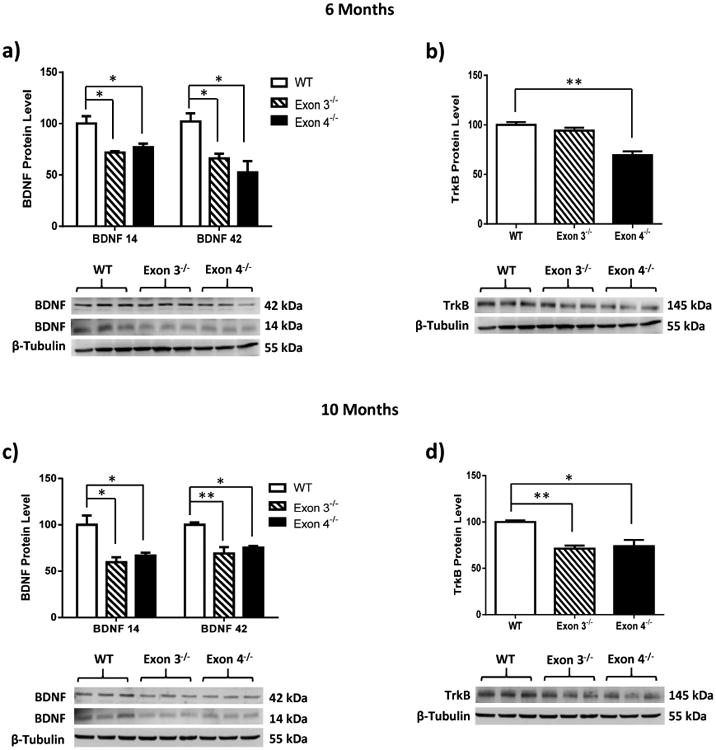

3.2. ERβ disruption downregulates BDNF and TrkB in female rat hippocampus

To further validate the findings from ER-/- mouse models, BDNF and TrkB expression levels were examined in two different ERβ mutant rat models in which the ERβ gene was disrupted by targeted deletion of exon 3 (Exon 3-/-) or exon 4 (Exon 4-/-). Animals were sacrificed at 6 months and 10 months of age (n= 5/group) and hippocampal tissues were collected and probed for BDNF immunoreactivity. Consistent with the findings in ERβ-/- mice, BDNF expression was significantly reduced in the hippocampus of both ERβ mutant rat models at 6 months (Figure 2a, monomeric BDNF: F(2, 6) = 10.07, p=0.0121; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 7.67, p=0.0222) and 10 months of age (Figure 2c, monomeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 9.90, p=0.0126; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 13.99, p=0.005). Additionally, a similar decrease in expression levels of TrkB was detected in Exon 4-/- rats at 6 months (Figure 2b, TrkB: F(2,6) = 25.52, p=0.0012) and both ERβ mutant rat models at 10 months of age (Figure 2d, TrkB: F(2,6) = 13.23, p=0.0063). These findings indicate that ERβ regulates the BDNF and TrkB expression level in the rat hippocampus and the importance of the ERβ DNA binding domain in mediating estrogen actions.

Figure 2. ERβ disruption downregulates BDNF and TrkB in female rat hippocampus.

BDNF and TrkB regulation by ERβ was further examined in the hippocampus of a-b) 6-month-old and c-d) 10-month-old ERβ mutant female rats. ERβ mutant rats with deletions of exon 3 or exon 4 leads to a significant reduction in the expression levels of BDNF and TrkB in rat hippocampus. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation, n=5. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

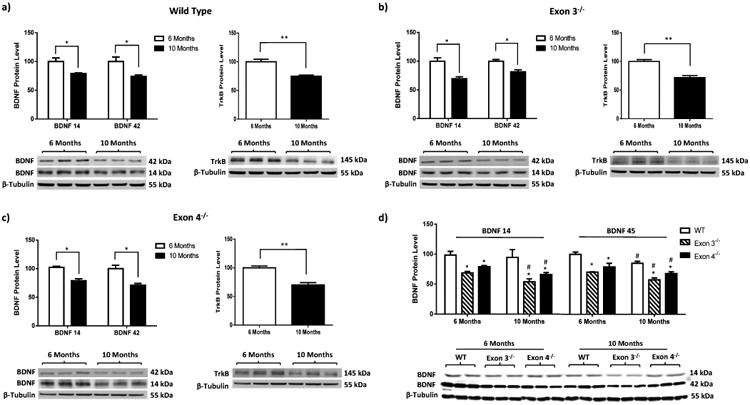

3.3. BDNF is more significantly impacted by ERβ status than aging

To better understand the biological significance of ERβ-mediated regulation of BDNF, an age-dependent comparison of hippocampal BDNF immunoreactivity was performed in 6-month and 10-month-old wild type and ERβ mutant rats (Figure 3). Consistent with the literature, the data indicated that aging from 6 months to 10 months leads to a significant decrease in BDNF and TrkB expression levels in all three rat models (Figure 3a-c). The comparison of both factors (ERβ status and age) on the same western blot revealed that ERβ disruption results in a 30%-40% decrease in BDNF expression levels while aging resulted in a 10%-15% reduction. Though both the aging process and disruption of ERβ result in a significant decline in BDNF expression levels, the data indicate that ERβ disruption more significantly impacts BDNF suggesting that the regulation of BDNF by ERβ is more prominent than the regulation of BDNF by aging (Figure 3d, monomeric BDNF: two-way ANOVA, Interaction: p=0.3062; column factor (effect of genotype): p=<0.0001; row factor (effect of aging): p=0.0040); trimeric BDNF: two-way ANOVA, Interaction: p=0.8742; column factor (effect of genotype): p=<0.0001; row factor (effect of aging): p=0.0011).

Figure 3. BDNF is more significantly impacted by ERβ status than aging.

BDNF regulation by ERβ and aging was comparatively examined in the hippocampus of 6 and 10-month-old ERβ mutant female rats. Data indicate that: a-c) Aging decreases BDNF and TrkB protein expression in rat hippocampus irrespective of ERβ status; d) ERβ disruption exerts a more prominent impact on BDNF in comparison to aging. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation, n=5. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. #p<0.05 comparison between 6 Months and 10 Months group.

3.4. ERβ activation upregulates BDNF and TrkB in primary hippocampal neurons

As ERβ deficiency was shown to significantly and negatively impact BDNF and TrkB expression, possible effects of ERβ activation on BDNF and TrkB expression levels was examined in primary hippocampal neurons treated with the ER subtype-specific agonists PPT (ERα agonist) and DPN (ERβ agonist). The data indicate that specific activation of ERβ but not ERα resulted in increased expression of BDNF in primary hippocampal neurons (Figure 4a, monomeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 28.06, p=0.0009; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 16.07, p=0.0039). The data also revealed that ERβ activation resulted in increased phosphorylation of the TrkB receptor (Figure 4b, F(2,6) = 14.76, p=0.0048). The ERβ-mediated upregulation of BDNF and TrkB was abolished in neurons pre-treated with the ERβ-specific antagonist PHTPP (Figure 4b, monomeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 8.9, p=0.0159; trimeric BDNF: F(2,6) = 69.51, p<0.001; TrkB: F(2,6) = 14.76, p=0.0048).

Figure 4. ERβ activation upregulates BDNF/TrkB signaling and synaptic markers in primary hippocampal neurons.

Primary hippocampal neurons were treated with PPT (100 nM), DPN (100 nM), or DPN (100 nM) in combination with PHTPP (1 μM). Data indicate that: a) Activation of ERβ but not ERα results in a significant increase in BDNF protein expression in primary hippocampal neurons; b-c) Activation of ERβ also leads to an increase in the expression levels of pTrkB and synaptic proteins synaptophysin, VAMP2, and PSD95; ERβ agonism-mediated increase was reverted back to basal levels in neurons co-treated with ERβ antagonist PHTPP. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation, n=3. *p<0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001.

3.5. ERβ activation upregulates the expression levels of synaptic proteins in primary hippocampal neurons

Antidepressants have been reported to increase the expression and function of proteins related to synaptic plasticity (O'Leary et al., 2009; Sairanen et al., 2007). Therefore, we assessed whether ERβ activation in primary hippocampal neurons would mimic the effects of antidepressant treatment. DPN and DPN plus PHTPP-treated neurons were harvested and probed for expression of the synaptic plasticity markers synaptophysin (major synaptic vesicle protein p38), VAMP2 (vesicle-associated membrane protein 2) and PSD95 (postsynaptic density protein 95) (Figure 4c). The data indicate that ERβ activation significantly upregulated the expression levels of synaptophysin, VAMP2, and PSD95 (Figure 4c, Synaptophysin: F(2,6) = 13.34, p=0.0062; VAMP2: F(2,6) = 14.30, p=0.0052; PSD95: F(2,6) = 28.6, p=0.0009). The DPN-mediated increased protein expression of all three markers was attenuated or abolished in neurons pre-treated with the ERβ-specific antagonist PHTPP, indicating that ERβ is a potential regulator of synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons that is likely mediated by BDNF signaling.

3.6. ERβ disruption upregulates 5-HT2A but has no effect on 5-HT1A in female rat hippocampus

After determining that ERβ does regulate BDNF expression in the hippocampus, we further examined the role of ERβ in the regulation of 5-HT signaling in the female rat hippocampus. As 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A have been implicated in the etiology of depression, our investigation was focused on these two 5-HT receptors. The data indicate that ERβ disruption had no effect on 5-HT1A expression levels in female rat hippocampus at either 6 months or 10 months of age (Fig. 5a and 5b, 6 month animals (5a): F(2,6) = 1.579, p=0.2812; 10 month animals (5b): F(2,6) = 0.9962, p=0.4231). However, ERβ disruption resulted in a nearly 15% increase in expression levels of 5-HT2A in the hippocampus of 6-month-old animals. In addition, this dysregulation was enhanced in 10-month-old ERβ mutant rats which showed nearly 40% increase in the expression level of 5-HT2A receptors (Fig. 5a and 5b, 6 month animals (5a): F(2,6) = 9.16, p=0.0150; 10 month animals (5b): F(2,6) = 34.63, p=0.0005). These results indicate that ERβ regulates 5-HT2A but not 5-HT1A in the female rat hippocampus, which may be enhanced by aging.

Figure 5. a-b) ERβ disruption upregulates 5-HT2A but has no effect on 5-HT1A in female rat hippocampus.

ERβ regulation of serotonergic receptors, 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A, was examined in the hippocampus of ERβ mutant female rats. Data indicate that ERβ mutant rats with deletions of exon 3 or exon 4 leads to an increase in 5-HT2A protein expression but has no effect on 5-HT1A in the hippocampus of both 6 and 10-month-old rats. c-d) TrkB activation downregulates 5-HT2A in primary hippocampal neurons. Interaction between BDNF/TrkB and 5-HT2A signling was examined in primary hippocampal neurons. Data indicate that: c) Activation of BDNF/TrkB negatively regulates 5-HT2A; d) Activation of 5-HT2A does not regulate BDNF/TrkB. Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation, n=3. *p<0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001.

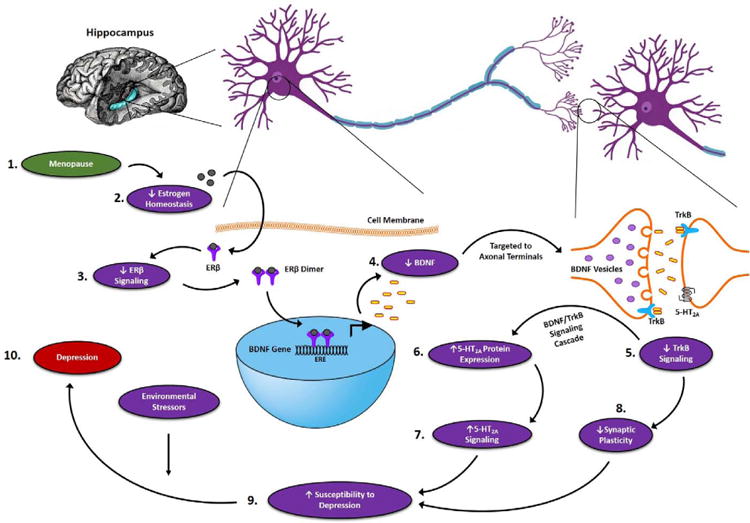

Figure 6. ERβ regulation of BDNF–5-HT2A signaling in the hippocampus of female brain.

Based on the above findings, we hypothesize that: (1) the onset of menopause results in (2) an irregular profile of estrogen in the brain. Disruption of estrogen homeostasis (3) decreases the activation of ERβ signaling in the brain. Decresed ERβ signaling results in reduced transcription of the BDNF gene, (4) decreasing BDNF protein levels in the hippocampus. Decreased BDNF protein levels leads to (5) decreased TrkB signaling, which through unknown mechanisms (6) increases 5-HT2A protein expression and (7) 5-HT2A-mediated signaling. The decrease in BDNF/TrkB signaling also leads to (8) downregulation of synaptic proteins, thus weakening the synaptic strength. Decreased BDNF/TrkB signaling and increased 5-HT2A signaling along with decreased neuroplasticity predispose the brain to (9) an increased risk of developing depression, which could be exacerbated by environmental stressors leading to (10) the onset of depression.

3.7. Activation of TrkB downregulates 5-HT2A in primary hippocampal neurons

In order to determine the possible interaction between the BDNF/TrkB and 5-HT2A-medaited signaling pathways, primary hippocampal neurons were treated with agonists of TrkB (7,8 DHF) or 5-HT2A receptor (DOI) and 5-HT2A and BDNF protein expression were examined via immunoblot analyses. The data demonstrate a 30-35% decrease in the levels of 5-HT2A after 7 days of treatment with 7, 8 DHF (Figure 5c, 4-day treatment: t=1.128, p=0.3580; 7-day treatment: t=7.547, p=0.0080) while treatment with DOI did not induce a significant change in the expression levels of either BDNF or pTrkB (Figure 5d, monomeric BDNF: F(3,8) = 1.914, p=0.2059; trimeric BDNF: F(3,8) = 0.9540, p=0.4596; pTrkB: F(3,8) = 0.6413, p=0.6096).

4. Discussion

This study sought to elucidate the role of ERs in the regulation of BDNF and 5-HT signaling, both of which have been highly implicated in the etiology of depression (Coppen, 1967; Duman and Monteggia, 2006). Analyses in ERα-/- and ERβ-/- mouse models demonstrated that BDNF was significantly downregulated in ERβ-/- but not ERα-/- mice, and the ERβ-mediated response was limited to the hippocampus. This brain region-specific regulation of BDNF is intriguing as it parallels clinical (Dwivedi et al., 2003) and preclinical observations (Duman and Monteggia, 2006; Lippmann et al., 2007) reporting decreased mRNA and protein levels of BDNF and TrkB in the hippocampus of depressed subjects, an observation which was reversed by chronic antidepressant treatment (Balu et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2003). These regional specificities could be related to the most robust expression of ERβ (Osterlund et al., 2000; Osterlund and Hurd, 2001) and BDNF (Conner et al., 1997; Ernfors et al., 1990; Hohn et al., 1990; Kawamoto et al., 1996; Yan et al., 1997) in hippocampal formation in comparison to other brain regions.

A number of studies have reported decreased BDNF mRNA in ovariectomized animals which was reversed by estradiol treatment (Cavus and Duman, 2003; Singh et al., 1995). Although this estrogen-mediated action has been extensively studied in the past, the underlying mechanism is still not clearly understood. Some studies have implicated the role of ERα (Calabrese et al., 2013) whereas other reports have supported a role for ERβ in mediating this effect (Li et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014). The results of this study showed that BDNF and its receptor TrkB are regulated specifically by ERβ and not ERα as only ERβ-/- animals showed decreased BDNF and TrkB expression in specific brain regions. This finding indicates that estrogen exerts its effects via ERβ, at least in the hippocampus, suggesting that the decreased estrogen signaling in menopause can lead to a subsequent disruption of ERβ signaling creating a deficit in BDNF signaling. The demonstrated regulation of BDNF by ERβ could possibly be occurring through the regulation of gene expression of BDNF by ERβ as an estrogen response element (ERE) has been reported in the BDNF gene (Sohrabji et al., 1995).

Antidepressants have been reported to increase the expression and function of proteins related to synaptic plasticity (O'Leary et al., 2009; Sairanen et al., 2007). Our data demonstrates that activation of ERβ results in a two-fold increase in the synaptic vesicle structural protein, Synaptophysin, 50% increase in VAMP2, a SNARE protein involved in the docking of vesicles to the presynaptic membrane, and a 50% increase in the expression of the postsynaptic density protein PSD95 when compared to vehicle treated neurons. These findings are in line with the outcomes of research studies which reported a similar increase in levels of synaptic proteins in the hippocampus of mice following treatment with ERβ but not ERα specific agonists (Liu et al., 2008), although contradictory results have also been reported (Jelks et al., 2007). Hence our data lend further support that ERβ agonism is indeed capable of inducing positive changes in synaptic proteins in hippocampal neurons. Accordingly, it is logical to postulate that the decreased ERβ signaling during the menopausal transition can lead to a downregulation of these synaptic proteins via decreased BDNF signaling, thus resulting in a weakened ability to adapt to environmental stressors, which have been associated with the onset of depressive episodes.

The monoamine theory is the oldest hypothesis proposed for understanding the etiology of depression (Schildkraut, 1965) and 5-HT is an important player in this hypothesis (Coppen, 1967). There are very few studies that have analyzed potential molecular mechanisms underlying the interactions of estrogen, BDNF, and 5-HT signaling, three signaling pathways that appear to converge in the hippocampus (for review see (Scharfman and MacLusky, 2006)). In the present study, expression levels of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A were analyzed, as these serotonergic receptors have been implicated in depressive disorders (for review see (Naughton et al, 2000)). Analyses in both 6 and 10-month-old ERβ mutant rats revealed an significant increase in expression levels of 5-HT2A, but there were no significant changes in the expression of the 5-HT1A receptor. These results correspond with clinical findings that have reported an increase in 5-HT2A receptor expression in depressed patients (Shelton et al., 2009) and antidepressant treatments ranging from SSRIs to monoamine oxidase inhibitors induce a downregulation of 5-HT2A receptor in postsynaptic regions in the brain (for review see (Gray and Roth, 2001)). Thus there appears to be a possibility that decreased ERβ signaling in menopause leads to a dysfunction in both BDNF and 5-HT2A signaling, which precipitates the onset of depression.

In order to determine whether the ERβ-regulated BDNF and 5-HT2A signaling pathways interact with one another, a direct approach of stimulating either 5-HT2A or TrkB signaling in primary hippocampal neurons followed by analyses of the expression levels of other signaling molecules was performed. There have been previous reports indicating that BDNF can regulate 5-HT2A (Trajkovska et al., 2009) in the hippocampus and vice versa (Vaidya et al., 1997). Our data revealed that 5-HT2A activation by DOI didn't lead to a significant change in the expression level of BDNF and pTrkB; in contrast, treatment with 7, 8 DHF significantly downregulated 5-HT2A in hippocampal neurons. These results indicate that BDNF is not being regulated by 5-HT2A, at least at the level of protein, but 5-HT2A is being regulated by BDNF in the hippocampus. Thus it is possible that during menopause decreased BDNF signaling leads to increased 5-HT2A activity, which heightens susceptibility for the development of mood disorders. Moreover, antidepressants have been shown to induce their effects after two to three weeks of time and the regulation we saw in our study mimics that time frame strengthening the possibility of antidepressants working via 5-HT2A receptor signaling.

Overall, the findings of this study are insightful but there remain issues that need to be futher addressed. Pro-BDNF is not only a precursor of mature BDNF but has been shown to act as a signaling molecule on its own. It has been proposed that mature and pro-BDNF exist in an equilibrium (Lu et al., 2005); interruption of the equilibrium potentially contributes to the development of depression. One of the weaknesses of this study is that the levels of pro-BDNF were not measured; however, the absence of these data does not reduce the significance of the findings. Changes in the mature form of BDNF were evident indicating a dyshomeostasis in the equilibrium, which would impact susceptibility to depression. Secondly, the use of neuronal cultures derived from both male and female fetuses represents another limitation of the study and the results obtained from these cultures need to be further examined in sex-specific neuronal populations. Lastly, it has been reported that ERβ knockout animals do not develop depression-like phenotype (Walf et al., 2009), suggesting that the loss of ERβ function alone is not sufficient to trigger a depressive episode, but instead requires interactions with environmental stressors to reach the threshold to cause depression.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide evidence for a possible mechanistic cascade underlying the increased susceptibility of depression in menopausal women (Figure 6). Based on these results, we hypothesize that menopause disrupts estrogen homeostasis which decreases the stimulation of ERβ-mediated estrogen signaling in the brain. The attenuated ERβ signaling leads to reduced transcription of the BDNF gene, thus decreasing the BDNF protein level in the hippocampal region of the brain. Decreased level of BDNF and reduced BDNF/TrkB signaling weakens synaptic strength thus compromising the brain's ability to adapt and increasing the risk of depression. Attenuated BDNF/TrkB signaling also increases the activity of 5-HT2A, which could contribute to the increased susceptibility to depression. These molecular changes are escalated in the presence of environmental stressors and lead to the development of depression in menopausal women. Further research is highly warranted to examine the pathophysiological and pharmacological significance of these mechanistic findings in the context of menopausal depression.

Highlights.

ERβ but not ERα regulates BDNF/TrkB signaling in the hippocampus of female brain.

ERβ agonism positively regulates synaptic proteins in hippocampal neurons.

ERβ disruption upregulates 5-HT2A but not 5-HT1A protein expression in the female hippocampus.

TrkB signaling negatively regulates 5HT2A protein expression in hippocampal neurons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Nancy Muma for providing the 5-HT2A antibody (Singh et al., 2007). This work was supported by grants from the NIH-funded Institutional Development Award (P20GM103418), the KUMC Institute for Reproductive Health and Regenerative Medicine, and the KU general research and start-up funds to LZ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balu DT, Hoshaw BA, Malberg JE, Rosenzweig-Lipson S, Schechter LE, Lucki I. Differential regulation of central BDNF protein levels by antidepressant and non-antidepressant drug treatments. Brain Res. 2008;1211:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese F, Guidotti G, Racagni G, Riva MA. Reduced neuroplasticity in aged rats: a role for the neurotrophin brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neurobiology of aging. 2013;34:2768–2776. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron S, Wallis C, Blakely A. Setting up an HIV-testing service with same-day results. Nursing times. 1995;91:33–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KE, Dennerstein L, Finch S, Szoeke CE. Impact of menopausal status on negative mood and depressive symptoms in a longitudinal sample spanning 20 years. Menopause. 2017;24:490–496. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavus I, Duman RS. Influence of estradiol, stress, and 5-HT2A agonist treatment on brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in female rats. Biological psychiatry. 2003;54:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celada P, Puig MV, Amargos-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F. The therapeutic role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. J Psychiatr Neurosci. 2004;29:252–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner JM, Lauterborn JC, Yan Q, Gall CM, Varon S. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:2295–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppen A. The biochemistry of affective disorders. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science. 1967;113:1237–1264. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, Aghajanian GK, Landis H, Heninger GR. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Archives of general psychiatry. 1990;47:411–418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham JS, Deakin JF, Miyajima F, Payton A, Toro CT. Expression of hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptors in Stanley consortium brains. Journal of psychiatric research. 2009;43:1175–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y, Rizavi HS, Conley RR, Roberts RC, Tamminga CA, Pandey GN. Altered gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and receptor tyrosine kinase B in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Archives of general psychiatry. 2003;60:804–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernfors P, Wetmore C, Olson L, Persson H. Identification of cells in rat brain and peripheral tissues expressing mRNA for members of the nerve growth factor family. Neuron. 1990;5:511–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feighner JP. Mechanism of action of antidepressant medications. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 1999;60(4):4–11. discussion 12-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer A, Benmansour S. Delayed pharmacological effects of antidepressants. Molecular psychiatry. 2002;7(1):S23–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta M, Numakawa T, Chiba S, Ninomiya M, Kajiyama Y, Adachi N, Akema T, Kunugi H. Estrogen, predominantly via estrogen receptor alpha, attenuates postpartum-induced anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in female rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:3807–3816. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Roth BL. Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5-HT(2A) receptors by agonists and antagonists. Brain research bulletin. 2001;56:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensler JG, Advani T, Monteggia LM. Regulation of serotonin-1A receptor function in inducible brain-derived neurotrophic factor knockout mice after administration of corticosterone. Biological psychiatry. 2007;62:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz M, Stein A, Uncini T. The discrediting of the monoamine hypothesis. International journal of general medicine. 2012;5:135–142. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S27824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Hirvonen J, Karlsson H, Kajander J, Lepola A, Markkula J, Rasi-Hakala H, Nagren K, Salminen JK, Hietala J. Decreased brain serotonin 5-HT1A receptor availability in medication-naive patients with major depressive disorder: an in-vivo imaging study using PET and [carbonyl-11C]WAY-100635. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum. 2008;11:465–476. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohn A, Leibrock J, Bailey K, Barde YA. Identification and characterization of a novel member of the nerve growth factor/brain-derived neurotrophic factor family. Nature. 1990;344:339–341. doi: 10.1038/344339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm KJ, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression. Drugs. 1999;57:607–631. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelks KB, Wylie R, Floyd CL, McAllister AK, Wise P. Estradiol targets synaptic proteins to induce glutamatergic synapse formation in cultured hippocampal neurons: critical role of estrogen receptor-alpha. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:6903–6913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0909-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto Y, Nakamura S, Nakano S, Oka N, Akiguchi I, Kimura J. Immunohistochemical localization of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 1996;74:1209–1226. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JH, Kwon IS, Kang EB, Lee CK, Lee NH, Kwon MG, Cho IH, Cho JY. Neuroprotective effects of treadmill exercise on BDNF and PI3-K/Akt signaling pathway in the cortex of transgenic mice model of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of exercise nutrition & biochemistry. 2013;17:151–160. doi: 10.5717/jenb.2013.17.4.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, Banasr M, Dwyer JM, Iwata M, Li XY, Aghajanian G, Duman RS. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329:959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1190287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, Bress A, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM, Monteggia LM. Long-term behavioural and molecular alterations associated with maternal separation in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3091–3098. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Day M, Muniz LC, Bitran D, Arias R, Revilla-Sanchez R, Grauer S, Zhang G, Kelley C, Pulito V, Sung A, Mervis RF, Navarra R, Hirst WD, Reinhart PH, Marquis KL, Moss SJ, Pangalos MN, Brandon NJ. Activation of estrogen receptor-beta regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity and improves memory. Nature neuroscience. 2008;11:334–343. doi: 10.1038/nn2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Pang PT, Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrn1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton M, Mulrooney JB, Leonard BE. A review of the role of serotonin receptors in psychiatric disorders. Hum Psychopharm Clin. 2000;15:397–415. doi: 10.1002/1099-1077(200008)15:6<397::AID-HUP212>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary OF, Wu X, Castren E. Chronic fluoxetine treatment increases expression of synaptic proteins in the hippocampus of the ovariectomized rat: role of BDNF signalling. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:367–381. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Gustafsson JA, Keller E, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression within the human forebrain: distinct distribution pattern to ERalpha mRNA. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2000;85:3840–3846. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptors in the human forebrain and the relation to neuropsychiatric disorders. Progress in neurobiology. 2001;64:251–267. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt LA, B D. NCHS data brief, no 172. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Gaynes BN, Nierenberg AA. STAR*D: revising conventional wisdom. CNS drugs. 2009;23:627–647. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarelainen T, Hendolin P, Lucas G, Koponen E, Sairanen M, MacDonald E, Agerman K, Haapasalo A, Nawa H, Aloyz R, Ernfors P, Castren E. Activation of the TrkB neurotrophin receptor is induced by antidepressant drugs and is required for antidepressant-induced behavioral effects. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:349–357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00349.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen M, O'Leary OF, Knuuttila JE, Castren E. Chronic antidepressant treatment selectively increases expression of plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Neuroscience. 2007;144:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakane T, Pardridge WM. Carboxyl-directed pegylation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor markedly reduces systemic clearance with minimal loss of biologic activity. Pharmaceutical research. 1997;14:1085–1091. doi: 10.1023/a:1012117815460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, MacLusky NJ. Estrogen and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in hippocampus: Complexity of steroid hormone-growth factor interactions in the adult CNS. Front Neuroendocrin. 2006;27:415–435. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut JJ. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. The American journal of psychiatry. 1965;122:509–522. doi: 10.1176/ajp.122.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PJ, Nieman L, Danaceau MA, Tobin MB, Roca CA, Murphy JH, Rubinow DR. Estrogen replacement in perimenopause-related depression: a preliminary report. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2000;183:414–420. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton RC, Sanders-Bush E, Manier DH, Lewis DA. Elevated 5-HT 2A receptors in postmortem prefrontal cortex in major depression is associated with reduced activity of protein kinase A. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1406–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Meyer EM, Simpkins JW. The effect of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement on brain-derived neurotrophic factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cortical and hippocampal brain regions of female Sprague-Dawley rats. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2320–2324. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Shi J, Zemaitaitis BW, Muma NA. Olanzapine increases RGS7 protein expression via stimulation of the Janus tyrosine kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling cascade. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2007;322:133–140. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Boylan C, Fritsche M, Altar CA, Lindsay RM. BDNF increases monoaminergic activity in rat brain following intracerebroventricular or intraparenchymal administration. Brain Res. 1996;710:11–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of general psychiatry. 2001;58:529–534. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F, Miranda RCG, Toranallerand CD. Identification of a Putative Estrogen Response Element in the Gene Encoding Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11110–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spires TL, Grote HE, Varshney NK, Cordery PM, van Dellen A, Blakemore C, Hannan AJ. Environmental enrichment rescues protein deficits in a mouse model of Huntington's disease, indicating a possible disease mechanism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:2270–2276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1658-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovska V, Santini MA, Marcussen AB, Thomsen MS, Hansen HH, Mikkelsen JD, Arneberg L, Kokaia M, Knudsen GM, Aznar S. BDNF downregulates 5-HT(2A) receptor protein levels in hippocampal cultures. Neurochemistry international. 2009;55:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya VA, Marek GJ, Aghajanian GK, Duman RS. 5-HT2A receptor-mediated regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the hippocampus and the neocortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:2785–2795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Koonce CJ, Frye CA. Adult female wildtype, but not oestrogen receptor beta knockout, mice have decreased depression-like behaviour during pro-oestrus and following administration of oestradiol or diarylpropionitrile. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:442–450. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser MJ, Wu TJ, Handa RJ. Estrogen receptor-beta agonist diarylpropionitrile: biological activities of R- and S-enantiomers on behavior and hormonal response to stress. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1817–1825. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leaf PJ, Holzer CE, 3rd, Myers JK, Tischler GL. The epidemiology of depression. An update on sex differences in rates. Journal of affective disorders. 1984;7:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(84)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels JM, Leyland NA, Agarwal SK, Foster WG. Estrogen induced changes in uterine brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptors. Human reproduction. 2015;30:925–936. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Depression 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Steven Richardson J, Li XM. Dose-related effects of chronic antidepressants on neuroprotective proteins BDNF, Bcl-2 and Cu/Zn-SOD in rat hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:53–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q, Rosenfeld RD, Matheson CR, Hawkins N, Lopez OT, Bennett L, Welcher AA. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein in the adult rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1997;78:431–448. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Tao J, Xu L, Zhao N, Chen J, Chen W, Zhu Y, Qiu J. Estradiol decreases rat depressive behavior by estrogen receptor beta but not alpha: no correlation with plasma corticosterone. Neuroreport. 2014;25:100–104. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Wang DD, Wang Y, Liu T, Lee FS, Chen ZY. Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism alters vulnerability to stress and response to antidepressants. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:4092–4101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5048-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]