Abstract

Objective:

This study attempted to determine if Housing First (HF) decreased suicidal ideation and attempts compared to treatment as usual (TAU) amongst homeless persons with mental disorders, a population with a demonstrably high risk of suicidal behaviour.

Method:

The At Home/Chez Soi project is an unblinded, randomised control trial conducted across 5 Canadian cities (Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal, Moncton) from 2009 to 2013. Homeless adults with a diagnosed major mental health disorder were recruited through community agencies and randomised to HF (n = 1265) and TAU (n = 990). HF participants were provided with private housing units and received case management support services. TAU participants retained access to existing community supports. Past-month suicidal ideation was measured at baseline and 6, 12, 18, and 21/24 months. A history of suicide attempts was measured at baseline and the 21/24-month follow-up.

Results:

Compared to baseline, there was an overall trend of decreased past-month suicidal ideation (estimate = –.57, SE = .05, P < 0.001), with no effect of treatment group (i.e., HF vs. TAU; estimate = –.04, SE = .06, P = 0.51). Furthermore, there was no effect of treatment status (estimate = –.10, SE = .16, P = 0.52) on prevalence of suicide attempts (HF = 11.9%, TAU = 10.5%) during the 2-year follow-up period.

Conclusion:

This study failed to find evidence that HF is superior to TAU in reducing suicidal ideation and attempts. We suggest that HF interventions consider supplemental psychological treatments that have proven efficacy in reducing suicidal behaviour. It remains to be determined what kind of suicide prevention interventions (if any) are specifically effective in further reducing suicidal risk in a housing-first intervention.

Keywords: suicide, homelessness, Housing First, randomised controlled trial, longitudinal study, community mental health services

Abstract

Objectif:

Cette étude tentait de déterminer si l’approche Logement d’abord (LD) a diminué l’idéation suicidaire et les tentatives de suicide comparativement au Traitement habituel (TH) chez les personnes sans abri souffrant de troubles mentaux, une population ayant manifestement un risque élevé de comportement suicidaire.

Méthode:

Le projet At Home/Chez Soi est un essai randomisé contrôlé sans insu mené dans 5 villes canadiennes (Vancouver, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montréal, Moncton) de 2009 à 2013. Des adultes sans abri ayant reçu un diagnostic de trouble de santé mentale majeur ont été recrutés dans des organismes communautaires et randomisés à Logement d’abord (n = 1265) et au Traitement habituel (n = 990). Les participants à Logement d’abord ont reçu un logement privé et des services de soutien de la gestion des cas. Les participants au Traitement habituel ont conservé l’accès aux soutiens communautaires existants. L’idéation suicidaire du mois précédent a été mesurée au départ, puis à 6, 12, 18, et 21 mois sur 24. Les antécédents de tentatives de suicide ont été mesurés au départ puis au suivi de 21 mois sur 24.

Résultats:

Comparativement au départ, il y a eu une tendance générale à la diminution de l’idéation suicidaire du mois précédent (Estimation = –0,57; ET = 0,05; p < 0,001), sans effet du groupe de traitement (c.-à-d., Logement d’abord contre Traitement habituel; Estimation = –0,04; ET = 0,06; p = 0,51). En outre, il n’y avait pas d’effet du type de traitement (Estimation = –0,10; ET = 0,16, p = 0,52) sur la prévalence des tentatives de suicide (LD = 11,9 %, TH = 10,5 %) durant le suivi de deux ans.

Conclusion:

Cette étude n’a pas réussi à prouver que l’approche Logement d’abord est supérieure au Traitement habituel pour réduire l’idéation suicidaire et les tentatives de suicide. Nous suggérons que les interventions de Logement d’abord envisagent des traitements psychologiques supplémentaires qui se sont révélés efficaces pour réduire le comportement suicidaire. Il reste à déterminer quel type d’interventions de prévention du suicide (le cas échéant) sont particulièrement efficaces pour réduire davantage le risque de suicide dans une intervention de Logement d’abord.

Introduction

Homelessness is associated with poor mental and physical health outcomes as well as high rates of mortality.1,2 Individuals who are homeless experience some of the highest rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts of any measured cohort.3 The magnitude of this risk is understood to be linked to a high prevalence of major mental disorders4 (e.g., drug/alcohol abuse and dependence) in addition to trauma, poor medication compliance, high rates of poverty, and limited social support networks.5 Similarly, high prevalence of homelessness comorbidities such as psychosis and alcohol dependence have been demonstrated across other studies.6,7 Amongst homeless individuals, Eynan et al.4 found that those with DSM-IV diagnoses of psychotic or mood disorders exhibited disproportionately high frequencies of suicidal ideation, at 100% and 64%, respectively. Comparing these values to the national lifetime average of 13.4% stresses the concerning level of risk demonstrated by this population.8

Although there is substantial literature regarding risk factors for suicidality in the general population, the extant literature on risk factors for homeless individuals is relatively limited. Suicidal behaviour is significantly related to comorbidity of mental disorders and addictions, coupled with poverty and social isolation.9,10 Unfortunately, these exacerbating factors also make treatment challenging. In a large study examining treatment of substance use disorders, it was noted that homeless individuals were significantly more likely to use emergency departments, were less likely to use outpatient resources, and had a greater likelihood of being arrested for a felony.11 Traditional community resources are not necessarily designed to address these unique risk factors of homelessness. Identifying and understanding demographic characteristics related to suicidality in this high-risk population may therefore be of notable clinical value.

Housing First (HF) is a treatment approach that is relatively new in practice and research; however, its principles have been used by an increasing number of cities over the past few decades.12–14 The model involves the provision of permanent, private housing units to qualifying individuals, with consumer choice on services and housing location being fundamental. Examination of HF programs in Vienna, Austria, identified that this aspect was crucial, presumably to ameliorate the stigma normally associated with living in state-run supportive housing units and the detriment it may have on long-term outcomes.15 HF has been shown to improve housing stability and quality of life.12,16 It has previously been demonstrated that lower quality of life is related to increased suicidal ideation.17 Furthermore, a 2013 review of homelessness literature noted a strong negative relationship between housing stability and completed suicides.6 It is therefore plausible that an intervention shown to improve housing stability, such as HF, may concomitantly reduce suicidal behaviour.

Objectives

In this study, we analysed data from a large unblinded pragmatic randomised controlled trial (At Home/Chez Soi) in Canada.18-24 Based on high rates of suicidal behaviour among homeless individuals and previous work showing improvements in quality of life and mental health among people receiving HF and moving out of poor neighbourhoods,25 we hypothesised that HF would reduce suicidal ideation and attempts compared to treatment as usual (TAU).

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted across 5 Canadian cities (Moncton, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, and Winnipeg) as an unblinded, randomised control trial, conducted under real-world conditions (i.e., pragmatic). Research was conducted in accordance with the At Home/Chez Soi Trial Protocol.22 Ethics approval was obtained through institutional review boards for the national At Home/Chez Soi project, as well as at each site and participating university. It was previously determined that a sample size of greater than 100 per group, per site would be required to detect a medium effect size for the trial’s primary outcomes (including housing stability and quality of life).23 The ability to detect changes in suicidal behaviour was assisted by the trial’s large sample size. Participants were recruited between 2009 and 2011, through community agencies such as drop-in centres and hospitals. Consent was obtained to undergo eligibility screening. Eligibility criteria included being of legal age of majority, being homeless or precariously housed,22 and the diagnosis or presence of a serious mental disorder (major depressive, manic or hypomanic episode, posttraumatic stress disorder, mood disorder with psychotic features, psychotic disorder) as identified by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).18 Current substance use or alcohol use disorders did not exclude participants from the study, but participants were required to also meet criteria for one of the aforementioned diagnoses to meet eligibility criteria. Participants were excluded if they did not meet eligibility criteria, if they were not legal residents of Canada, or if they were already clients of assertive community treatment (ACT)/intensive case management (ICM) programs.

Intervention

The intervention group was HF, while the control was TAU. HF was further subdivided into ACT and ICM case management modalities. Prior to randomisation, participants were individually assessed to determine their level of need using the ACT eligibility criteria.26 This assessment included the Multnomah Community Ability Score (MCAS), MINI, and an eligibility-screening questionnaire. High-need individuals were defined as having an MCAS score of 61 or lower and diagnosis of current psychotic or bipolar disorder. Additionally, they identified as having 2 or more hospitalisations for mental illness in the past 5 years, comorbid substance use, or recent arrests/incarceration(s). Those determined to be of high need were assigned to the ACT group after randomisation. All others were categorised as moderate need and assigned to ICM after randomisation, which involves less-intensive provision of services than the ACT program.23 Randomisation was completed by a computerised algorithm, which adaptively controlled the number of participants in each group to achieve equality. Those randomised into HF were immediately connected with either the ACT or ICM services, depending on their prior needs assessment. ICM/ACT service provision may include home visits, medication dispensing, phone calls, and so on. Those randomised into TAU were directed to existing community resources, which include supports, such as homeless outreach and support centers, and mental health resources.

HF participants were provided housing within the community, with the goal of placement within 6 weeks of entering the program. It was preferred that all housing be ‘permanent’ in the form of individual apartments, as opposed to supportive (continuum or congregate housing with built-in mental health supports, often temporary in nature).27 Rent was subsidised so that participants would not have to pay more than 30% of their income for rent. HF participants were neither required to seek/undergo psychiatric treatment nor maintain sobriety. Participants were, however, required to meet with support service providers, consistent with the aforementioned ICM/ACT models, at least once a week. Participants were not required to use additional resources unless they chose to do so.

Procedure

Data were collected from each group in the form of interviews, during which a member of the At Home/Chez Soi project administered an extensive series of questionnaires addressing the domains of demographics, housing, work, physical/mental health, and service use, amongst others. Ethnicities and gender were self-reported. Interviews were conducted between June 2009 and October 2013. Interviews were conducted at baseline and 6-, 12-, 18-, and 21/24-month time points. (In some cases, the comprehensive 24-month interview was combined with the less-intensive 21-month interview for logistical reasons.)

Measures

Suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation was assessed using a question from the 14-item Modified Colorado Symptom Index (MCSI), which asked, ‘In the past month, how often did you feel like hurting or killing yourself?’28 Participants responded on a 5-point scale from not at all to at least every day. Any response greater than not at all was coded as positive for the presence of suicidal ideation. Participants were administered the MCSI at baseline and 6-, 12-, 18-, and 21/24-month time points. Participants were directed to available mental health resources if this or any other question elicited or suggested suicidal ideation/mental deterioration during the interview.

Suicide attempts

The presence of lifetime suicide attempts was assessed using a question from the MINI 6.0.0,29 which was administered at the baseline interview. Participants were asked the yes/no question, ‘In your lifetime, did you ever make a suicide attempt?’ The presence of a suicide attempt during the course of the 2-year study was assessed at the 21/24-month interview with the question, ‘Since you started this study, that is, in the past 2 years, have you attempted suicide?’

Analytic Strategy

Suicidal ideation

Linear growth modeling (LGM) was used in Mplus 7.1 to model changes in suicidality over time, given the repeated measurement nature of participants’ self-reported suicidality. Because LGM permits participants to differ in both their starting level of suicidality (i.e., intercept) as well as their rate of suicidality change over time (i.e., slope), it is possible to examine the influence of predictors on these growth model parameters.30,31

First, we identified a basic model to describe the prevalence of suicidality (as a binary outcome variable) over time, including intercept (i.e., baseline suicidality) and slope (i.e., changes in suicidality over time) values. A maximum likelihood estimator was specified that uses a logistic model for categorical outcomes and a numerical integration algorithm.30 Consistent with standard LGM procedures, the mean of the intercept was fixed at 0, while the mean of the slope and variances of the intercept and slope factors were allowed to vary. This allowed us to determine if there was significant whole-group change in suicidality over time and/or significant between-subject variance in suicidality slope or intercept.

Next, we examined the role of sociodemographics, psychiatric diagnoses, and intervention status in predicting both baseline suicidality and changes in suicidality over time. This included an investigation of whether treatment status (i.e., participation in the HF intervention vs. TAU) predicted initial presence of suicidality (i.e., intercept) or change in suicidality over time (i.e., slope). In addition, this model controlled for (and examined the effects of) sociodemographics (age, gender, ethnicities, education, income, lifetime homelessness), baseline psychiatric diagnosis (mood disorder, PTSD, panic disorder, psychotic disorder, substance or alcohol use disorder), and lifetime suicide attempt history (presence vs. absence) covariates.

Suicide attempts

A logistic regression was conducted in Mplus 7.1 to determine the influence of intervention status on suicide attempts during the intervention period. In addition to measuring the influence of HF v. TAU intervention status on suicide attempts during the study period, we also controlled for (and examined the effects of) the sociodemographic factors listed above.

Missing Data

At baseline, there were minimal missing data across variables (<0.1%-5.2%). The one exception was ethnicities, in which 13.3% of participants had missing data. Longitudinally, 14.3% to 22.2% of suicidal ideation and 20.2% of suicide attempt data were missing at a given time point. Intervention status was not related to missing suicidal behaviour data at any time point (P > 0.05). Given the nature of the study population, it was anticipated that there would be a potentially large amount of missing data. Therefore, in all models, a full-information maximum likelihood estimator allowed us to estimate parameters using all available data from participants due to pairwise deletion, so participants with missing data could be included in analyses.

Results

Sociodemographics

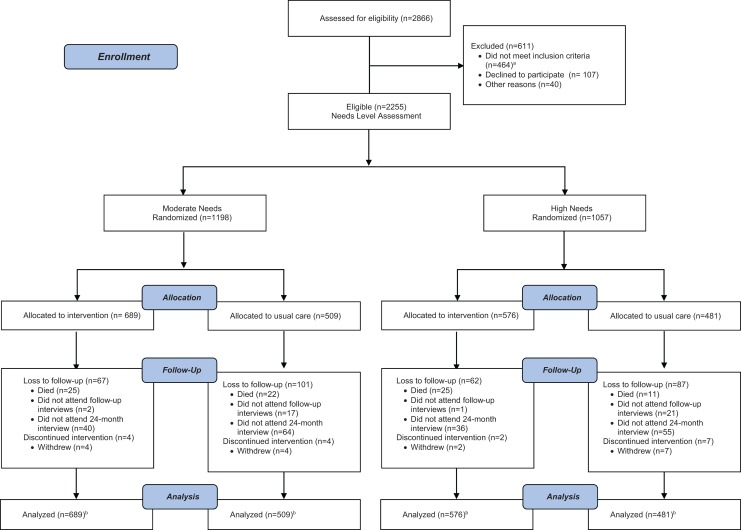

Of the 2866 participants assessed for eligibility, 2255 were included in the trial, and 2221 were included in this analysis (Figure 1). Of those analysed, 67.9% were male, 49.0% were white, and 24.8% were aboriginal. As per our inclusion criteria, all participants had a diagnosed baseline mental disorder, with the most prevalent being mood disorders (56.5%). In addition, two-thirds of the sample (67.4%) met criteria for substance/alcohol abuse (Table 1). Baseline rates of lifetime suicide attempts were high (55.4%), as was past-month suicidal ideation (37.3%). Participants were randomised into HF (n = 1236) and TAU (n = 985).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants throughout the study (CONSORT). aParticipants were excluded from the study if they did not meet the study inclusion criteria with respect to (1) age, (2) homelessness status, and (3) the presence of a mental disorder based on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview or (4) if they were currently served by an assertive community treatment (ACT) or intensive case management team or (5) lacked legal status in Canada. bThirty-four participants (29 in the intervention group, 5 in the usual care group) were excluded from the final analysis as per national trial protocol.22

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic Sample Descriptives.

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 2221; 100%) | Housing First (n = 1236; 55.7%) | Treatment as Usual (n = 985; 44.3%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | |||

| Years, mean (SD) | 40.89 (11.23) | 40.78 (11.15) | 41.02 (11.33) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 1508 (67.9) | 834 (67.5) | 674 (68.4) |

| Female | 603 (31.2) | 395 (32.0) | 298 (30.3) |

| Other | 20 (0.9) | 7 (0.6) | 13 (1.3) |

| Ethnicities, n (%) | |||

| White | 940 (49.0) | 555 (50.5) | 385 (47.0) |

| Indigenous | 475 (24.8) | 276 (25.1) | 199 (24.3) |

| Other | 504 (26.3) | 268 (24.4) | 236 (28.8) |

| Baseline psychiatric diagnoses, n (%) | |||

| Mood disorder (MDE and manic) | 1255 (56.5) | 699 (56.6) | 556 (56.4) |

| PTSD | 645 (29.0) | 360 (29.1) | 285 (28.9) |

| Panic disorder | 511 (23.0) | 270 (21.8) | 241 (24.5) |

| Psychotic disorder | 1095 (49.3) | 640 (48.2) | 499 (50.7) |

| Substance or alcohol use disorder | 1498 (67.4) | 823 (66.6) | 675 (68.5) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| < High school | 1241 (56.1) | 704 (57.2) | 537 (54.7) |

| ≥ High school diploma | 970 (43.7) | 526 (42.8) | 444 (45.3) |

| Monthly income at baseline, n (%) | |||

| $0.00 to $399.99 | 654 (29.4) | 362 (29.3) | 292 (29.6) |

| $400.00 to $799.99 | 740 (33.3) | 403 (32.6) | 337 (34.2) |

| $800.00 to highest | 827 (37.2) | 471 (38.1) | 356 (36.1) |

| Lifetime homelessness at baseline, n (%) | |||

| <12 months | 640 (28.8) | 357 (28.9) | 283 (28.7) |

| 12-36 months | 576 (25.9) | 313 (25.3) | 263 (26.7) |

| >36 months | 1005 (45.2) | 566 (45.8) | 439 (44.6) |

Percentages are valid percentage of sample and exclude missing data. MDE, major depressive episode; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Suicidal Ideation

The basic growth model indicated a significant overall decline in suicidal ideation over time (slope: estimate = –.57, SE = .05, P < 0.001), as well as significant variance in both intercept (estimate = 2.53, SE = .38, P < 0.001) and slope (estimate = .22, SE = .05, P < 0.001). Descriptively, rates of suicidal ideation decreased from 37.3% to 21.3% in the entire study population between baseline and 21/24-month time points (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptives of Outcome Variables.

| Variable | Total Sample (N = 2221; 100%), n (%) | Housing First (n = 1236; 55.7%), n (%) | Treatment as Usual (n = 985; 44.3%), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide attempts (% yes) | |||

| Baseline (past month) | 113 (5.6) | 63 (5.6) | 50 (5.6) |

| Lifetime | 1167 (55.4) | 652 (55.6) | 515 (54.0) |

| Prevalence during 2-year study period | 200 (11.3) | 124 (11.8) | 76 (10.5) |

| Suicide ideation (past month) | |||

| Prevalence (> never) | |||

| Baseline | 814 (37.3) | 442 (36.4) | 372 (38.4) |

| Month 6 | 470 (26.5) | 262 (24.5) | 208 (29.5) |

| Month 12 | 470 (24.7) | 277 (24.8) | 193 (24.6) |

| Month 18 | 384 (22.2) | 219 (21.3) | 165 (23.5) |

| End | 378 (21.3) | 232 (22.1) | 146 (20.1) |

In the full-growth model, treatment condition (HF vs. TAU) did not predict significant variance in suicidal ideation baseline rates (intercept) or changes over time (slope). There were, however, multiple covariate predictors of suicidal ideation intercept and slope (Table 3). Specifically, a higher baseline rate of suicide ideation was predicted by younger age and presence of various mental disorders, including mood disorder, PTSD, panic disorder, psychotic disorder, and substance use disorder. A positive slope (higher likelihood of suicidal ideation over time) was predicted by aboriginal ethnicities relative to white ethnicities.

Table 3.

Predictors of Change in Suicidal Ideation during the 2 Years of At Home/Chez Soi Housing First Intervention.

| Baseline Predictors of Suicidal Ideation Frequency | Growth Model Intercept, Estimate (SE) | Growth Model Slope, Estimate (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male reference group | .01 (.05) | .09 (.06) |

| Age | ||

| Continuous, in years | –.01* (.00) | .00 (.00) |

| Ethnicities | ||

| Aboriginal (vs. white) | –.16 (.07) | .24** (.08) |

| Other (vs. white) | –.07 (.07) | .03 (.07) |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | ||

| Presence (vs. absence) | .02 (.05) | .03 (.05) |

| Baseline psychiatric diagnoses | ||

| Mood disorder (MDE and manic) | .59*** (.05) | .17 (.11) |

| PTSD | .34*** (.06) | .04 (.07) |

| Panic disorder | .22** (.06) | –.05 (.06) |

| Psychotic disorder | .14** (.05) | .08 (.06) |

| Substance or alcohol use disorder | .22*** (.06) | .02 (.06) |

| Income | ||

| $500 to $1000 (vs. <$500) | .05 (.07) | –.00 (.06) |

| >$1000 (vs. <$500) | –.05 (.07) | –.03 (.07) |

| Education | ||

| ≥ High school equivalent (vs. < high school equivalent) | –.00 (.05) | .03 (.05) |

| Lifetime homelessness | ||

| 3-12 months (vs. <3 months) | .03 (.07) | –.04 (.07) |

| >1 year (vs. <3 months) | –.06 (.06) | –.05 (.06) |

| Intervention status | ||

| Housing First (vs. TAU) | .07 (.05) | –.01 (.05) |

MDE, major depressive episode; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; TAU, treatment as usual.

*P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Suicide Attempts

The logistic regression models predicting suicide attempts from intervention status and covariates also indicated no significant relationship between intervention status and suicide attempts (estimate = .10, SE = .16, P > 0.05). Covariates that predicted higher rates of suicide attempts over the 2-year project period included younger age, lifetime homelessness less than 3 months, and a baseline diagnosis of either mood disorder or PTSD. Notably, a lifetime history of suicide attempts at baseline was not predictive of the presence of suicide attempts during the study (Table 4). Models predicting suicidality and suicide attempts were also run separately for ICM and ACT groups, but no intervention effects were found, and sociodemographic and mental health results were highly similar.

Table 4.

Predictors of Suicide Attempt during the 2 Years of At Home/Chez Soi Housing First Intervention (at 24-Month Interview).

| Predictors of Suicide Attempt during the 2-Year Study | Estimate (SE) | Logistic Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | (ref) | 1.00 |

| Female (vs. male) | 0.12 (0.16) | 1.13 (0.87-1.46) |

| Age | ||

| (Continuous) | –0.02* (0.01) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

| Ethnicities | ||

| White | (ref) | 1.00 |

| Indigenous | 0.40 (0.20) | 1.49 (1.07-2.08) |

| Other | –0.37 (0.24) | 0.69 (0.46-1.03) |

| Lifetime suicide attempt | ||

| No attempt | (ref) | 1.00 |

| Attempt | 0.05 (0.16) | 1.05 (0.80-1.37) |

| Baseline psychiatric diagnoses (no diagnosis as ref) | ||

| Mood disorder | 0.53** (0.19) | 1.70 (1.25-2.31) |

| PTSD | 0.39* (0.17) | 1.47 (1.12-1.95) |

| Panic disorder | 0.25 (0.18) | 1.38 (0.95-1.72) |

| Psychotic disorder | 07 (0.17) | 1.08 (0.82-1.42) |

| Substance or alcohol use disorder | 0.34 (0.20) | 1.40 (1.00-1.95) |

| Income | ||

| <$500 | (ref) | 1.00 |

| $500 to $1000 | 0.01 (0.20) | 1.01 (0.73-1.39) |

| >$1000 | 0.17 (0.21) | 1.18 (0.83-1.67) |

| Education | ||

| ≥ High school equivalent | (ref) | 1.00 |

| < High school equivalent | –0.14 (0.16) | 0.87 (0.67-1.14) |

| Lifetime homelessness | ||

| <3 months | (ref) | 1.00 |

| 3-12 months | –0.49* (0.21) | 0.61 (0.44-0.86) |

| >1 year | –0.45* (0.19) | 0.64 (0.47-0.87) |

| Intervention status | ||

| Treatment as usual | (ref) | 1.00 |

| Housing First | 0.10 (0.16) | 1.11 (0.85-1.44) |

PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

*P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

There are 3 main findings from the current study. First, during the 2 years of follow-up, HF was not associated with reductions in suicidal ideation or attempts compared to TAU. Second, both intervention and control groups experienced similarly significant drops in suicidal ideation over the course of the 2-year study. Third, the baseline presence of mood disorder, PTSD, panic disorder, psychotic disorder, and substance use disorder was associated with later suicidal behaviour.

There is an absence of published literature examining the impact of HF on suicidal behaviour for comparison. In our study, it is possible that there was regression to the mean with nonspecific impact of both TAU and HF arms having reductions in suicidal behaviour. Given the intensive, longitudinal nature of our trial, participants from both groups interacted with the At Home/Chez Soi team repeatedly over the course of 2 years. As a result, the TAU group may have been too ‘active’ a control condition to see a difference between groups. One may consider that engagement in the trial could have provided individuals in both groups with a sense of social connection, apparent concern for their well-being, and a sense of purpose. Research by Okamura et al.32 suggests that ‘perceived emotional social support is a significant protective factor for recent suicidal ideation’, more so than instrumental support. It is therefore plausible that outcomes in the control group improved because they experienced the research team as a caring social support. Furthermore, participants in the TAU group may have developed a sense of hope that, as the trial concluded, they could be able to take advantage of the resources provided to the HF group.

While it is possible that HF’s lack of demonstrated efficacy over TAU in this trial is due to type II error, the large sample size reduces this possibility, and negligible observed effect sizes suggest that both groups were relatively similar. Another key consideration is that the HF intervention arms did not have any evidence-based interventions focused on suicidal behaviour. A recent systematic review of suicide prevention strategies identifies specific interventions that may be effective at reducing suicidality, including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), certain pharmacotherapy interventions, and restricting lethal means.33 Crucially, these therapies only work if they are directed towards suicidal behaviour and its features, and they are not effective if reducing suicidal behaviour is not the primary intent of the therapy.34 This has recently been defined as the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide (CAMS) approach, which identifies suicidality as a target of intervention rather than a symptom of pathology.35 Furthermore, this has resulted in the creation of specific Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP) programs.36 Given that HF is not a suicide-focused intervention, these methods may be effective within the HF model, as they can be offered as options within the program, without breaking the HF tenet of not forcing treatment compliance. However, the efficacy of any particular method remains to be determined.

Our investigation also discovered relationships between suicidal behaviour and a variety of mental disorders. In particular, we found that baseline mood disorder and PTSD were significant predictors of both higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. These findings are consistent with previous findings within similar populations, as well as in the general population.4,10,37 These findings underscore the importance of treatment of these disorders to reduce risk for suicidal behaviour.

Age was found to be inversely related to both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. An inverse relationship was also discovered between suicide attempts and lifetime homelessness. This is consistent with current literature, describing that homeless persons are more likely to be younger and become homeless earlier in life.38-40 Although chronic homelessness (>1 year consecutively homeless) is related to poorer clinical outcomes than those homeless for shorter periods,2 it seems that individuals with recent onset of homelessness (i.e., < 3 months) are at an exaggerated risk for suicidality. Homelessness often results from the coalescing of multiple factors, often culminating in an acute life event/stressor when one first loses stable housing.41,42 Taking these factors into account, we suggest that rates of suicidal behaviour may be higher initially, due to the combined impacts of being homeless and unresolved stressors, such as employment difficulties and relationship challenges.43 This is consistent with literature describing an increased number of acute stressing life events amongst individuals who have attempted suicide.44 Individuals who are older and/or have been homeless for a longer period of time may have either resolved their past life stressors or have better emotional regulation or developed coping skills, which may result in lower rates of suicidal behaviour. This emphasises the importance of early intervention amongst newly homeless young persons in the prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour.

A few notable limitations were present within this study. As detailed earlier, there was variation between trial sites in the provision and implementation of the program. Similarly, there is a potential for selection bias during recruitment. This trial was also unblinded, although this was necessary given its nature. Despite having trained interviewers surveying the participants, the trial is still based on questionnaires and may be affected by response bias and/or errors in recall. Suicidal ideation and attempts were each assessed through a single question and may not comprehensively assess either condition, potentially masking differences between groups. Furthermore, the use of the MCSI and MINI to measure suicidal ideation and attempts, respectively, does not take into account the potential impact of other self-harm behaviour. Independent variables such as childhood abuse, exposure to trauma, and specific self-harm behaviour were not studied. While the missing data were collectively not statistically different in any measure from the group that remained in the trial, the absolute number of missing data was high. The findings are not generalizable to completed suicides. This study’s strengths include its large, multisite sample population, 2-year longitudinal data, and comprehensive participant follow-up.

Conclusions

This research fails to find evidence that HF is superior to TAU in reducing suicidal ideation and attempts. Equally significant decreases in suicidal ideation in both groups may in part be due to actively engaging all participants in the trial with comprehensive surveys given by research team members and increasing perceived social/interpersonal support. While we suggest that HF should not be used solely as a mechanism to decrease suicidal behaviour, its previously demonstrated positive effects on quality of life and housing stability may set the stage for improved long-term follow-up and enhanced access to care. HF models may benefit from the addition of suicide-focused therapies such as CBT, DBT, restriction of lethal means, novel CBT-SP programs, and/or utilisation of the CAMS approach to successfully decrease suicidal behaviour in this high-risk group. Clinicians should continue to be cognizant of the high prevalence of suicidality amongst the homeless population and should not reduce their index of concern for suicidal behaviour when engaging with the participants of HF programs.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Trial Registration: International Standard Randomized Control Trial Number Register Identifier: ISRCTN42520374 (http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN42520374).

Trial Protocol: Goering PN, Streiner DL, Adair C, Aubry T, Barker J, Distasio J, Hwang SW, Komaroff J, Latimer E, Somers J, et al. The At Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a Housing First intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000323.

Role of the Sponsors: The Mental Health Commission of Canada oversaw the conduct of the study and provided training and technical support to the service teams and research staff throughout the project. However, the funder had no role in the analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

List of At Home/Chez Soi Investigators: National Team: Carol E. Adair, PhD; Tim Aubry, PhD; Paula Goering, PhD; Geoffrey Nelson, PhD; Myra Piat, PhD; Sanjeev Sridharan, PhD; David Streiner, PhD; Sam Tsemberis, PhD. Moncton: Saïd Bergheul, PhD; Jimmy Bourque, PhD; Paul-Émile Bourque, PhD; Pierre-Marcel Desjardins, PhD; Stefanie R. LeBlanc, MA; Danielle Nolin, PhD; Sarah Pakzad, PhD; John Sylvestre, PhD. Montreal: Jean-Pierre Bonin, PhD; Anne G. Crocker, PhD; Henri Dorvil, PhD; Marie-Josée Fleury, PhD; Roch Hurtubise, PhD; Eric A. Latimer, PhD; Alain Lesage, MD; Christopher McAll, PhD; Catherine Vallée, PhD; Helen-Maria Vasiliadis, PhD. Toronto: Ahmed M. Bayoumi, MD; Stephen W. Hwang, MD; Bonnie Kirsch, PhD; Maritt Kirst, PhD; Kwame McKenzie, MD; Rosane Nisenbaum, PhD; Patricia O’Campo, PhD; Vicky Stergiopoulos, MD. Winnipeg: James M. Bolton, MD; Daniel G. Chateau, PhD; Jino Distasio, PhD; Murray W. Enns, MD; Laurence Y. Katz, MD; Patricia J. Martens, PhD; Jitender Sareen, MD; Mark J. Smith, MSc. Vancouver: Lauren Currie, MPH; James Frankish, PhD; Michael R. Krausz, MD, PhD: Lawrence McCandless, PhD; Akm Moniruzzaman, PhD; Tonia L. Nicholls, PhD; Anita Palepu, MD; Michelle L. Patterson, PhD; Stefanie N. Rezansoff, MSc; Christian G. Schutz, MD, PhD; Julian M. Somers, PhD; Verena Strehlau, MD; Denise Zabkiewicz, PhD.

References

- 1. Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O’Connell JJ, et al. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(8):625–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Desai RA, Liu-Mares W, Dausey DJ, et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a sample of homeless people with mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(6):365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eynan R, Langley J, Tolomiczenko G, et al. The association between homelessness and suicidal ideation and behaviors: results of a cross-sectional survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(4):418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frederick TJ, Kirst M, Erickson PG. Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation among street-involved youth in Toronto. Adv Ment Health. 2012;11(1):8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bauer LK, Baggett TP, Stern TA, et al. Caring for homeless persons with serious mental illness in general hospitals. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(1):14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fekadu A, Hanlon C, Gebre-Eyesus E, et al. Burden of mental disorders and unmet needs among street homeless people in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Med. 2014;12:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Government of Canada. The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gopikumar V, Narasimhan L, Easwaran K, et al. Persistent, complex and unresolved issues: Indian discourse on mental ill health and homelessness. Econ Pol Wkly. 2015;50(11):42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldstein G, Luther JF, Haas GL. Medical, psychiatric and demographic factors associated with suicidal behavior in homeless veterans. Psychiatry Res. 2012;199(1):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krupski A, Graves MC, Bumgardner K, et al. Comparison of homeless and non-homeless problem drug users recruited from primary care safety-net clinics. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;58:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schiff JW, Rook J. Housing first: where is the evidence? Toronto, ON: Homeless Hub Press; 2012:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(4):651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsemberis S, Kent D, Respress C. Chronically homeless persons with co-occurring disorders in Washington, DC. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weinzierl C, Wukovitsch F, Novy A. Housing first in Vienna: a socially innovative initiative to foster social cohesion. J Hous Built Environ. 2016;31(3):409–422. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stergiopoulos V, Gozdzik A, O’Campo P, et al. Housing first: exploring participants’ early support needs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(167):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fairweather-Schmidt AK, Batterham PJ, Butterworth P, et al. The impact of suicidality on health-related quality of life: a latent growth curve analysis of community-based data. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goering P, Veldhuizen S, Watson A, et al. National At Home/Chez Soi Final Report. Calgary, AB: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2014:48.

- 19. Macnaughton E, Nelson G, Goering P. Bringing politics and evidence together: policy entrepreneurship and the conception of the At Home/Chez Soi housing first initiative for addressing homelessness and mental illness in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2013;82:100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson G, Macnaughton E, Curwood SE, et al. Collaboration and involvement of persons with lived experience in planning Canada’s At Home/Chez Soi project. Health Soc Care Community. 2016;24(2):184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nelson G, Macnaughton E, Goering P, et al. Planning a multi-site, complex intervention for homeless people with mental illness: the relationships between the national team and local sites in Canada’s At Home/Chez Soi project. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;51(3-4):347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goering PN, Streiner DL, Adair C, et al. The At Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: a pragmatic, multi-site, randomised controlled trial of a Housing First intervention for homeless individuals with mental illness in five Canadian cities. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stergiopoulos V, Hwang SW, Gozdzik A, et al. Effect of scattered-site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management on housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness. JAMA. 2015;313(9):905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Macnaughton E, Stefanic A, Nelson G, et al. Implementing Housing First across sites and over time: later fidelity and implementation evaluation of a pan-Canadian multi-site Housing First program for homeless people with mental illness. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;55(3-4):279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337(6101):1505–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Program Standards for ACT Teams. Toronto, ON: Ontario ACT Association; 2004. Updated 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Macnaughton EL, Goering PN, Nelson GB. Exploring the value of mixed methods within the At Home/Chez Soi housing first project: a strategy to evaluate the implementation of a complex population health intervention for people with mental illness who have been homeless. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(7, suppl 1):eS57–eS63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Conrad KJ, Yagelka JR, Matters MD, et al. Reliability and validity of a modified Colorado Symptom Index in a national homeless sample. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3(3):141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: statistical analysis with latent variables: user’s guide. Los Angeles (CA): Muthén & Muthén; 1998. –2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duncan T, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling: concepts, issues, and applications. 2nd ed Mahwah (NJ; ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Okamura T, Ito K, Morikawa S, et al. Suicidal behavior among homeless people in Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(4):573–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):646–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Modif. 2008;32(1):77–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. The Joint Commission. Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. Sentinel Event Alert. 2016;(56):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chaudhury SR, Chesin MS, Stanley B. Cognitive-behavioral approaches to treating the suicidal patient In: Lamis DA, Kaslow NJ, eds. Advancing the science of suicidal behavior: understanding and intervention. New York: Columbia University, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2014. p 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoertel N, Franco S, Wall MM, et al. Mental disorders and risk of suicide attempt: a national prospective study. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(6):718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christensen RC. Commentary on suicide and homelessness: what differentiates homeless persons who died by suicide from other suicides in Australia? A comparative analysis using a unique mortality registry. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(4):591–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ha Y, Narendorf SC, Santa Maria D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to shelter utilization among homeless young adults. Eval Program Plann. 2015;53:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gaetz S, Donaldson J, Richter T, Gulliver T. État de l’itinérance au Canada. Toronto, ON: Canadian Homelessness Research Network Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. McVicar D, Moschion J, van Ours JC. From substance use to homelessness or vice versa? Soc Sci Med. 2015;136-137:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clark J, Peiperl L, Veitch E, et al. Homelessness is not just a housing problem. PLoS Med. 2008;5(12):1639–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN, Cole SR, et al. Ongoing life stressors and suicidal ideation among HIV-infected adults with depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:322–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baca-Garcia E, Parra CP, Perez-Rodriguez MM, et al. Psychosocial stressors may be strongly associated with suicide attempts. Stress Health. 2007;23(3):191–198. [Google Scholar]