Abstract

Objective

Previous studies have indicated that patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), display significant differences in their kinetic and kinematic gait characteristics when compared to healthy, aged-matched controls. The ability of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to ambulate is also limited. These limitations are likely due to pathology-driven muscle morphology and physiology alterations establish in PAD and COP, respectively. Gait changes in PAD were compared to gait changes due to COPD to further understand how altered limb muscle due to disease can alter walking patterns. Both groups were independently compared to healthy controls. It was hypothesized that both patients with PAD and COPD would demonstrate similar differences in gait when compared to healthy controls.

Methods

Patients with PAD (n =25), patients with COPD (n =16), and healthy older control subjects (n =25) performed five walking trials at self-selected speeds. Sagittal plane joint kinematic and kinetic group means were compared.

Results

Peak values for hip flexion angle, braking impulse, and propulsive impulse were significantly reduced in patients with symptomatic PAD compared to patients with COPD. After adjusting for walking velocity, significant reductions (p < 0.05) in the peak values for hip flexion angle, dorsiflexor moment, ankle power generation, propulsion force, braking impulse, and propulsive impulse were found in patients with PAD compared to healthy controls. No significant differences were observed between patients with COPD and controls.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that while gait patterns are impaired for patients with PAD, this is not apparent for patients with COPD (without PAD). PAD (without COPD) causes changes to the muscle function of the lower limbs that affects gait even when subjects walk from a fully rested state. Altered muscle function in patients with COPD does not have a similar effect.

Keywords: Gait, Peripheral artery disease, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Vascular disease, Kinematics, Kinetics

1. Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are diseases that produce substantial exercise limitation in the affected patients [1,2]. Patients with either disease generally present with reduced muscular strength [3–6]. Previous studies have suggested that PAD significantly alters locomotor function [7–10] whereas, functional changes are not as pronounced in patients with COPD [11,12]. The impairments arising from these pathologies at a functional level, challenges the ability of affected patients to maintain independent living. Therefore, a primary focus for patients with PAD and patients with COPD is the assessment and rehabilitation of physical function. Physical activity produces a higher metabolic energy demand that requires an increased supply of oxygenated blood to the muscles compared to resting conditions. PAD substantially affects the delivery of blood to the legs even at submaximal exercise levels [13]. The effect of COPD differs with the delivery of oxygenated blood not limiting in patients at submaximal exercise levels [14]. Whether the deficiencies arising from these diseases impair gait biomechanics in a similar manner is not known, but it is important for exercise rehabilitation protocols.

1.1. Peripheral artery disease

PAD is a disease characterized by atherosclerosis, which is blockage of arteries due to plaque accumulation, and causes reduced supply of oxygenated blood to peripheral tissues. The most common symptom associated with PAD is intermittent claudication, defined as ischemia induced discomfort, pain, or cramping, which causes the patient to stop walking [10]. Advanced biomechanical analyses have determined the kinetic and kinematic alterations in patients with PAD [7–10]. Prior to claudication onset, patients with PAD have a significantly decreased propulsive (anterior-posterior) and vertical components of ground reaction forces (GRF) compared to healthy controls. Patients with PAD also demonstrate functional impairments through decreased walking speed and cadence [10]. In addition, patients with PAD present with greater ankle plantarflexion angle during early stance, reduced time to peak plantarflexion, and increased time to peak dorsiflexion [10]. These kinematic changes result in an altered rollover shape of the foot, which interferes with the optimal transfer of energy that typically occurs in healthy individuals [15]. Patients with PAD have significantly reduced peak ankle power generation at push-off, hip power generation at toe off, hip power absorption in mid stance, and knee power absorption in early and late stance [7,8]. Changes to the optimal gait result in less efficient walking patterns that corroborate with insufficient oxygen delivered to the leg muscles; increasing claudication pain and decreasing quality of life overall.

1.2. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In 2010, COPD was reported to be the third leading cause of death in the United States with over 137,000 reported cases [16]. COPD is characterized by progressive and persistent expiratory airflow limitations associated with chronic inflammation of the airway [17]. COPD limits ventilation causing dynamic hyperinflation when expiratory time is insufficient to permit lung emptying [18]. This can occur during physical activity and imposes constraints on tidal volume, and leads to dyspnea [12,19]. Patients with COPD may experience exacerbations, or acute instances of disease worsening [20]. One-third of patients with severe COPD experience 15 min or less of physical activity each day [21]. Studies have indicated that slow-twitch oxidative (type-1) muscle fibers decrease in favor of fast-twitch (type-2) anaerobic muscle fibers in this population [22]. This shift suggests decreased endurance during physical activity in patients with COPD. The severity of COPD symptoms is correlated with gait abnormalities [11], with severe COPD linked to slower walking speeds [23,24], reduced cadence [25], reduced step length, increased double support time [26] and more altered step time and width variability [27]. These may be associated with balance deficiencies detected for patients with COPD [28]. Muscular deficiencies have also been observed with a reduction in push-off force following a no-rest condition [5,29], and patients with COPD found to have weaker dorsiflexor and plantar flexor muscles and greater fatigability of distal leg muscles [4].

The mechanisms of impairment differ between the pathologies. In PAD, physical activity induced ischemia restricts blood supply. In COPD, airflow is restricted due to altered lung structure. Our group and others have previously demonstrated that oxygen delivery was not the only factor limiting function in PAD patients, but that mitochondrial dysfunction restricts the efficient use of the already limited nutrients and oxygen further lowering the energy levels of pathologic muscle [13,30–33]. Patients with COPD also exhibit altered muscle mitochondria function with evidence of decreased mitochondrial density and biogenesis, impaired mitochondrial respiration, and increased mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species in biopsies of the vastus lateralis [34,35].

Limitations in blood supply to the muscles can be reversed by surgery for patients with PAD, however these interventions do not enable patients to return to the activity levels of healthy subjects [36,37]. Medication can be used to improve the endurance in patients with COPD who do not develop muscle fatigue during exercise, but may not be effective when contractile fatigue is present [38]. It is important to understand how the different disease mechanisms, alter the ability of lower limb muscles to contribute to efficient gait. Currently, there are no guidelines on whether exercise intervention should be prescribed to patients with COPD and if so, what those exercise programs should entail. Those programs that do exist for patients with PAD [39] are not standardized and the effectiveness may vary. The understanding of how disease mechanisms in PAD and COPD alter lower limb function is useful information in determining how to mitigate the effect of these diseases [40,41]. It can potentially facilitate the design of specific interventions or recommendations for supervised exercise programs aimed to restore gait and independence to patients with PAD and patients with COPD.

The aim of this research was to differentiate the functional alterations associated with each disease by investigating changes in gait kinetics and kinematics associated with PAD prior to the onset of pain and compare them to the changes in gait of patients with COPD while at rest. We hypothesized that after accounting for reduced walking velocity, both PAD and COPD patient groups would have similarly altered kinematic and kinetic gait characteristics compared to healthy individuals during a rested condition.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Three groups of subjects were recruited for the analysis: 1) patients with bilateral PAD (fontaine stage II), 2) patients with COPD, and 3) healthy elderly control subjects. The University’s Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Review Board at the Omaha VA Medical Center approved all study procedures. Informed consent was obtained for each individual involved in the study. All subjects were able to understand instructions and independently perform the required experimental tasks, such as walking on a treadmill.

Twenty-five patients with PAD were recruited from the vascular surgery clinics of the Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center of Nebraska and Western Iowa, and the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha. Patients were screened and evaluated by two board-certified vascular surgeons. The screening procedure included a detailed medical history, physical examination, computerized tomographic angiography, hemodynamic assessment and direct evaluation and observational analysis of walking impairments. Ankle-brachial index levels below 0.9 and symptomatic claudication were inclusion criteria. Patients were excluded from participating in the study if they had gait deficiencies caused by comorbidities, such as cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular, or musculoskeletal disease. Additionally, patients with PAD who experienced pain or discomfort during walking for reasons other than claudication pain such as arthritis, low back pain, peripheral neuropathy, or musculoskeletal pain were excluded from this study.

Sixteen patients with COPD were recruited from the Pulmonary Clinical Studies Unit at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the general clinics of the Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center of Nebraska and Western Iowa to participate in the study. All patients with COPD were screened by a board-certified nurse practitioner. The patients were diagnosed with COPD by a combination of history, clinical exam, and lung function testing. All patients had a measured FEV1/FVC (represents the proportion of a person’s vital capacity that they are able to expire in the first second of forced expiration) less than 0.7 [42]. Patients were free from other co-morbidities that affect gait including musculoskeletal problems, PAD (all patients had an ankle-brachial index greater than 0.9), or neurologic disorders.

Twenty-five, age, height, and body mass matched, healthy individuals, were recruited for this study. Participants presented with no cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular, or musculoskeletal disease or pain. Individuals were excluded if they presented with a history of back or lower extremity injury, surgery that affected the subject’s mobility, or any other process limiting the ability to walk, such as neurologic disorders. These individuals had an FEV1/FVC greater than 0.7 and an ankle-brachial index greater than 0.9.

2.2. Study design and procedures

All participants underwent a biomechanical data collection protocol. Subjects wore a tight fitting suit to enable accurate placement of 33 retro-reflective markers on specific anatomical locations in accordance with a modified Helen Hayes marker set as described previously [10,43]. Subjects walked over a 10 m path at their self-selected speed while 3-dimensional marker trajectories (Motion Analysis Corp, Santa Rosa, CA; 60 Hz) and ground reaction forces were simultaneously collected (600 Hz; Kistler Group, Winterhur, Switzerland).

Each subject walked across the pathway until five valid trials were obtained for each foot. Subjects were instructed to walk forward naturally so they did not intentionally target the force plate. A valid trial met the following criteria: 1) no unnatural gait alterations (change in step length or cadence) before or after foot contact with the force plate; 2) heel-strike and toe-off events within the boundaries of the force plate; and 3) contact with the force plate with only one foot. To ensure pain or fatigue was not present during any of the trials, subjects were seated for a minimum of one minute between trials, or for as long as was required for pain to completely subside.

2.3. Data analysis

Foot strikes from the right limb were analyzed for all healthy controls and patients with COPD. In PAD, the affected limb with the lowest ankle-brachial index and greatest symptoms of claudication was chosen for analysis as this was considered the primary mobility-limiting limb. Marker trajectories were filtered with a zero lag, low-pass Butterworth filter with cutoff frequencies chosen using the method described by Jackson [44]. Kinematic and ground reaction force kinetic data were combined and analyzed (Visual 3D, C-Motion Inc., Germantown, MD) using an inverse dynamics method to quantify the peak joint moments and powers which occurred during the gait cycle [45]. Forces, joint moments, and joint powers were normalized to body mass. The peak values for vertical, anterior-posterior, and medial-lateral forces; and peak sagittal joint angles, moments, and powers served as the dependent variables for analysis of the lower extremity.

2.4. Statistical analysis

A 1 × 3 ANOVA analyzed differences between groups (mean ± SD) for each dependent variable (SPSS version 22 software, IBM, Armonk, NY). When a significant main effect occurred, (α= 0.05; Bonferroni correction applied where appropriate) a Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was conducted. Additionally, separate ANCOVA models were used to investigate the association of disease condition with dependent variable after adjusting for walking velocity. The ANCOVA analysis was performed due to the known differences in walking velocity between groups [10,22,23].

3. Results

Subject groups were of similar age, height and body mass, while a significant difference in walking velocity was found (Table 1). Post-hoc testing showed that patients with PAD walked slower than controls. The patients with COPD had an FEV1/FVC of 0.51 (±0.16). All patients with PAD except three, were affected bilaterally and had an ankle-brachial index of 0.44 (±0.20) for the most affected leg and 0.63 (±0.26) for the lesser (bilateral patients)/non-affected (unilateral patients) limb.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of age, height, mass, and walking velocity of each group. A significant difference was observed for walking speed, with post-hoc tests indicating the PAD group was significantly different from the Control group.

| Control (n = 25) Mean (SD) |

PAD (n = 25) Mean (SD) |

COPD (n = 16) Mean (SD) |

F2,63 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.4 (6.9) | 64.4 (8.0) | 63.8 (8.8) | 0.686 | 0.507 |

| Height (cm) | 1.72 (0.10) | 1.74 (0.07) | 1.72 (0.09) | 0.589 | 0.558 |

| Mass (kg) | 86.9 (23.6) | 91.3 (24.7) | 88.40 (24.6) | 0.212 | 0.810 |

| Velocity (m/s) | 1.17 (0.16) | 1.02 (0.20) | 1.11 (0.18) | 4.062 | 0.022 |

3.1. ANOVA results (Table 2)

Table 2.

Peak joint angle moment and power, forces, and impulses for each dependent variable. Results of ANOVA and ANCOVA with velocity as a covariate. Variables which have a significant main effect between groups are shown in bold type.

| Dependent Variable Mean (SD) | Control | PAD | COPD | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| (n = 25) | (n = 25) | (n = 16) | F2,63 | p-value | F2,61 | p-value | |

| Peak Angles (degrees) | |||||||

| Plantarflexion Angle | 5.6 (3.3) | 5.9 (4.3) | 7.1 (2.9) | 0.86 | 0.427 | 0.85 | 0.434 |

| Dorsiflexion Angle | 12.9 (4.1) | 13.61 (4.05) | 13.0 (3.2) | 0.25 | 0.778 | 0.18 | 0.837 |

| Knee Flexion Angle | 14.7 (6.1) | 13.58 (5.68) | 14.0 (6.4) | 0.21 | 0.813 | 0.21 | 0.808 |

| Knee Extension Angle | 2.5 (3.7) | 2.86 (3.82) | 2.5 (5.3) | 0.06 | 0.937 | 0.01 | 0.990 |

| Hip Flexion Angle | 37.6 (5.9) | 31.0 (5.2) | 36.5 (6.8) | 8.72a,b | < 0.001 | 4.98a,b | 0.010 |

| Hip Extension Angle | 3.2 (5.0) | 4.6 (4.4) | 4.2 (4.6) | 0.6 | 0.553 | 2.06 | 0.136 |

| Peak Forces (N/Body Weight) | |||||||

| Impact Vertical Force | 1.13 (0.12) | 1.06 (0.08) | 1.09 (0.09) | 3.32a | 0.043 | 1.45 | 0.243 |

| Vertical Force at Midstance | 0.80 (0.12) | 0.81 (0.06) | 0.79 (0.09) | 0.35 | 0.705 | 1.39 | 0.256 |

| Push-off Vertical Force | 1.09 (0.11) | 1.02 (0.06) | 1.08 (0.09) | 4.14a | 0.020 | 3.06 | 0.054 |

| Braking Force | 0.17 (0.04) | 0.13 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.04) | 5.97a | 0.004 | 1.83 | 0.170 |

| Propulsive Force | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.03) | 0.17 (0.04) | 8.52a | 0.001 | 4.00a | 0.023 |

| Medial Force | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.013 | 0.988 | 0.01 | 0.992 |

| Lateral Force | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) | 2.02 | 0.141 | 0.82 | 0.446 |

| Peak Moments (N*m/kg) | |||||||

| Plantarflexor Moment | 1.39 (0.13) | 1.32 (0.24) | 1.41 (0.15) | 1.59 | 0.211 | 0.73 | 0.487 |

| Dorsiflexor Moment | 0.38 (0.10) | 0.25 (0.08) | 0.32 (0.08) | 12.95a,b | < 0.001 | 7.85a | 0.009 |

| Knee Flexor Moment | −0.16 (0.14) | −0.20 (0.13) | −0.20 (0.15) | 0.702 | 0.500 | 1.25 | 0.294 |

| Knee Extensor Moment | 0.74 (0.25) | 0.53 (0.21) | 0.63 (0.22) | 5.12a | 0.009 | 1.92 | 0.155 |

| Hip Flexor Moment | −0.81 (0.22) | −0.71 (0.22) | −0.75 (0.28) | 1.17 | 0.316 | 0.05 | 0.954 |

| Hip Extensor Moment | 0.55 (0.13) | 0.45 (0.11) | 0.57 (0.17) | 4.97a,b | 0.01 | 2.26 | 0.112 |

| Peak Powers (J/kg) | |||||||

| Ankle Power Absorption 1 | −0.60 (0.25) | −0.44 (0.21) | −0.54 (0.23) | 2.87 | 0.064 | 0.28 | 0.760 |

| Ankle Power Absorption 2 | −0.92 (0.41) | −0.71 (0.27) | −0.90 (0.35) | 2.82 | 0.067 | 1.72 | 0.187 |

| Ankle Power Generation | 2.45 (0.49) | 1.96 (0.61) | 2.49 (0.50) | 6.78a,b | 0.002 | 3.42a | 0.039 |

| Knee Power Absorption 1 | −0.94 (0.56) | −0.59 (0.38) | −0.71 (0.44) | 3.46a | 0.037 | 0.96 | 0.388 |

| Knee Power Generation | 0.47 (0.30) | 0.27 (0.16) | 0.41 (0.22) | 4.36a | 0.017 | 1.49 | 0.233 |

| Knee Power Absorption 2 | −0.72 (0.25) | −0.49 (0.27) | −0.66 (0.35) | 4.33a | 0.017 | 1.47 | 0.238 |

| Hip Power Generation 1 | 0.38 (0.19) | 0.28 (0.22) | 0.43 (0.19) | 3.26 | 0.045 | 2.04 | 0.139 |

| Hip Power Absorption | −0.71 (0.28) | −0.58 (0.22) | −0.57 (0.24) | 2.2 | 0.119 | 1.26 | 0.290 |

| Hip Power Generation 2 | 0.66 (0.25) | 0.51 (0.18) | 0.60 (0.25) | 3.04 | 0.055 | 0.45 | 0.639 |

| Impulse (N*s/kg) | |||||||

| Braking Impulse | −0.41 (0.13) | −0.26 (0.06) | −0.40 (0.16) | 10.58a,b | < 0.001 | 7.94a,b | 0.001 |

| Propulsive Impulse | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.40 (0.16) | 10.53a,b | < 0.001 | 9.02a,b | < 0.001 |

Significant post-hoc between Control vs. PAD.

Significant post-hoc between PAD vs. COPD.

3.1.1. Weight acceptance

Kinematic measurements showed a significant main effect for peak hip flexion angle. Post hoc testing showed that this was due to patients with PAD showing less flexion at the hip than both the control group and the patients with COPD. There was no difference in hip flexion between patients with COPD and the control group. Anterior-posterior braking force was significantly lower for the PAD group when compared to the control group, while braking impulse was significantly lower compared to both the control group and the COPD group. Vertical forces during the initial loading phase was decreased for patients with PAD compared to controls. Joint moments revealed a significant main effect for ankle dorsiflexors and hip extensors. Post hoc testing resulted in the patients with PAD having significantly lower ankle and hip moments than the control and COPD groups. Regarding powers, there were significant main effects for knee power absorbed and hip power generated during weight acceptance. Post-hoc tests found that knee power absorbed by patients with PAD was significantly lower than controls.

3.1.2. Single-limb support

The only significant main effects during single limb support were found for knee extensor moments, and knee power generation. Post-hoc tests indicate patients with PAD had significantly reduced knee extensor moment and knee power generation compared to controls.

3.1.3. Propulsion

There were significant main effects for push-off vertical force, anterior-posterior propulsive force, propulsive impulse, ankle power generation, and knee power absorption during the propulsion phase of gait. Post-hoc tests of all these parameters showed values were significantly smaller for patients with PAD than controls. Patients with PAD also generated significantly less ankle power than patients with COPD.

3.2. ANCOVA results (Table 2; Figs. Fig. 1 and Fig. 2)

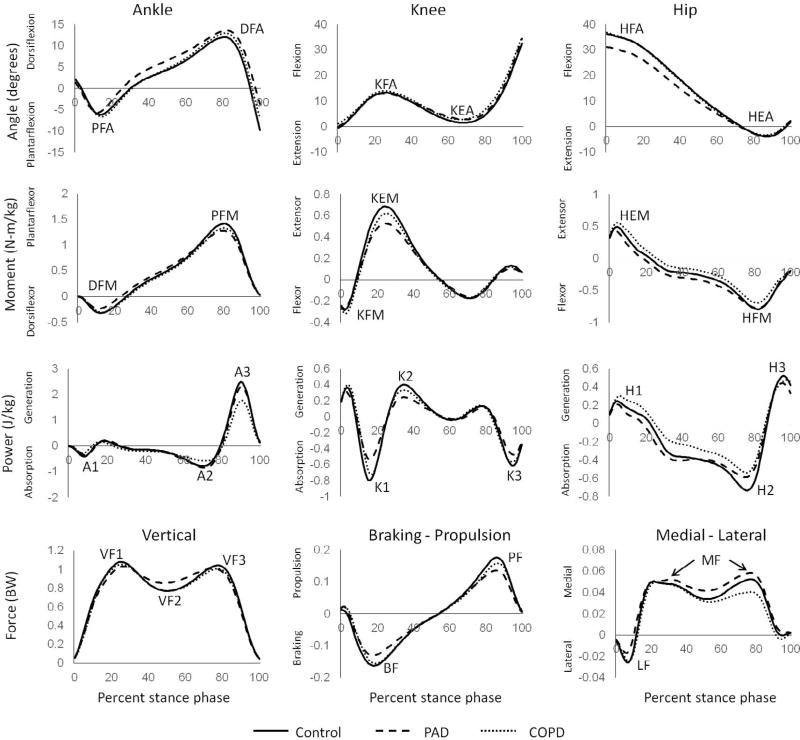

Fig. 1.

Ensemble average stance phase curves showing angles, moments, and powers in the sagittal plane of the ankle, knee and hip and the vertical, braking-propulsion, and medial-lateral forces. Labels for peaks are as follows: PFA – peak plantarflexion angle; DFA – peak dorsiflexion angle; KFA – Peak knee flexion angle; KEA – peak knee extension angle; HFA – peak hip flexion angle; HEA – peak hip flexion angle; DFM – peak dorsiflexor moment; PFM – peak plantarflexor moment; KFM – peak knee flexor moment; KEM – peak knee extensor moment; HFM – peak hip flexor moment; A1–peak ankle power absorption during early stance; A2–peak ankle power absorption during mid to late stance; A3–peak ankle power generation; K1–peak knee power absorption during early stance; K2–peak knee power generation during mid stance; K3–peak knee power absorption during late stance; H1–peak hip power generation during early stance; H2–peak hip power absorption during mid to late stance; H3–peak hip power generation during late stance; VF1–peak vertical force during early stance; VF2–minimum vertical force during midstance; VF3–peak vertical force during late stance; BF – peak braking force; PF – peak propulsive force; MF – peak medial force; LF – peak lateral force. Variable which were significantly different between groups for ANCOVA are indicated by an asterisk (*) next to the name.

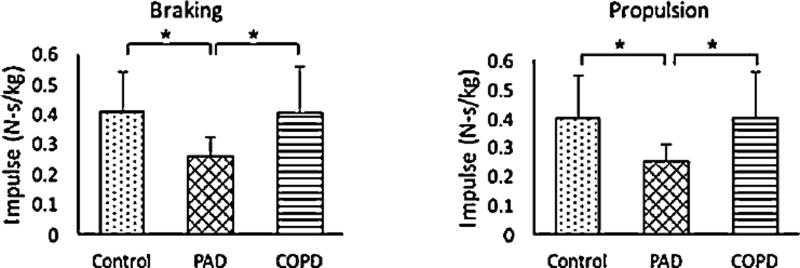

Fig. 2.

Peak braking and propulsive impulses during stance phase for control subjects and patients with PAD and COPD after adjustment for self-selected walking speed. Significant differences * (p < 0.01).

After adjusting for velocity as a covariate significant differences between groups remained for six of the 14 dependent variables that were significant in the ANOVA. Below are the results presented based on phase of gait.

3.2.1. Weight acceptance

Peak hip flexion angle was significantly reduced when compared to the control group and the patients with COPD. Differences observed for unadjusted braking impulses, remained after adjusting for velocity. Patients with PAD exhibited reduced braking impulse when compared to both control subjects, and patients with COPD. Peak ankle dorsiflexor moment was lower for the patients with PAD when compared to the control group but not when compared to the patients with COPD.

3.2.2. Single-limb support

There were no significant main effects during the single-limb support phase of stance.

3.2.3. Propulsion

Ankle power generation at push-off was reduced for patients with PAD when compared to healthy age matched control subjects. Differences at propulsion were observed in propulsive (anterior-posterior) ground reaction force. Patients with PAD produced significantly lower propulsion forces than the control group. Similarly, differences observed for unadjusted propulsion impulses, remained after adjusting for velocity. Patients with PAD produced lower propulsive impulse than control subjects, and patients with COPD.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to compare biomechanical gait abnormalities between patients with PAD, patients with COPD, and controls. All three groups walked at their preferred speed from a rested state. We hypothesized that PAD and COPD patient groups would have altered kinematic and kinetic gait parameters compared to healthy individuals. Our results only partly support this hypothesis. Patients with PAD displayed significant differences in lower limb kinematics and kinetics when compared to both COPD patients and healthy controls, however no significant differences were observed between the patients with COPD and healthy controls.

Patients with symptomatic PAD present with a clinically documentable chronic gait impairment in contrast to healthy elderly controls and patients with COPD. It is apparent from the results that the different mechanisms of PAD and COPD do not cause the same gait alterations for patients that are in a rested condition. The observed differences in the gait of patients with PAD were similar to those observed in previous studies [7–10,46]. Patients with PAD walked more slowly than patients with COPD and control subjects. When patients with PAD were velocity matched to control subjects in an earlier study [8] deficiencies in joint powers continued to be observed. A previous study [29] which did not adjust for walking velocity, showed minimal differences for patients with COPD when walking in a rested condition compared to a control group. Patients with COPD in the current study, walked at a similar speed to the control group, while other studies have reported that patients with COPD walk more slowly than controls [5]. These results suggest that the capacity of rested lower extremity muscles to produce force quickly is more compromised for patients with PAD than those suffering from COPD. Reduced walking speed alone with have an adverse effect on the quality of life of patients with PAD, compared to patients with COPD.

Chronic lower extremity ischemia in PAD has been associated with a well-described myopathy characterized at the histological level by myofiber degeneration, fibrosis and fatty infiltration and at the biochemical level by defective mitochrondrial function, and increased oxidative stress [30,31]. The myopathy of PAD is likely a key contributor to the observed weakness of the dorsiflexor, and hip extensor muscle groups [47,48]. Perhaps more important for forward progression is the inability of the ankle and knee to generate force at the rate of healthy individuals, as reflected in reduced power generation during mid and late stance [49]. The ankle in particular provides a significant proportion of the lower extremity power at push-off [50]. Development of improved exercise and rehabilitation protocols should address the reduced power generation capabilities at the ankle, perhaps by incorporating functional strength exercises.

No differences were observed in the current study for patients with COPD in a rested condition. This study and others in the past demonstrate that PAD myopathy restricts gait capacity even when the patient starts walking after being well rested [7,51]. The differences between groups can likely be attributed to muscle morphological, biochemical and strength alterations found in PAD but not COPD. A number of the evaluated patients with COPD were managing their disease using appropriate medications that optimized their lung function. Nonetheless COPD is associated with fatigue at exercise intensities that would otherwise not create fatigue in this age cohort [52], and previous investigations have suggested that patients with COPD have significantly altered gait following a no rest (after onset of fatigue) condition [29]. Future investigations exploring gait alterations as a function of exercise time and perceived fatigue in patients with COPD as well as cumulative gait alterations that result if both diseases are present concurrently will likely shed additional light into the mobility limitations caused by these diseases. The sample size of 16 patients with COPD may be adequate to reflect the gait of a homogeneous group, however due to the range of COPD phenotypes which may have been present and low severity of disease, gait impairments could have been minimized in the COPD cohort. Blood oxygen levels were not recorded so the level of oxygenation during the test is not known for the patients with COPD.

The results show that gait deficits are apparent in patients with PAD prior to the onset of pain whereas deficits are not apparent in patients with COPD prior to the onset of fatigue. Our data suggest that reduced ankle plantar flexor function is the main source of reduced walking ability for patients with PAD. Reduced peak hip flexion angles likely result from shorter step lengths, which have consistently been documented in patients with PAD [8,53,54]. Future studies should investigate step length in combination with walking speed to determine potential reasons for reduced hip flexion angles in patients with PAD. These data support findings of prior works from our group and others showing that claudicating patients typically gather around the extreme low end of the physical activity continuum and experience a severe decline in all domains of physical function. Future studies are required to determine the ability of different exercise protocols to treat the gait impairments of [55] patients with PAD and COPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Holly DeSiegelaere, Jeff Kaipust and Amanda Fletcher for their roles in data collection.

Dr. Stephen Rennard is employed by AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK and also retains Professorship and a part-time appointment at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA. Dr. Rennard reports personal fees from ABIM, personal fees from Able Associates, personal fees from Advantage Healthcare, personal fees from Align2Action, personal fees from Almirall, personal fees from APT, personal fees from ATS, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Baxter, personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, personal fees from Cheisi, personal fees from CIPLA, personal fees from ClearView Healthcare, personal fees from Cleveland Clinic, personal fees from CME Incite, personal fees from Complete Medical Group, personal fees from COPDFoundation, personal fees from Cory Paeth, personal fees from CSA, personal fees from CSL, personal fees from CTS Carmel, personal fees from Dailchi Sankyo, personal fees from Decision Resources, personal fees from Dunn Group, personal fees from Easton Associates, personal fees from Elevation Pharma, personal fees from FirstWord, personal fees from Forest, personal fees from Frankel Group, personal fees from Gerson, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Gilead, personal fees from Grifols, personal fees from GroupH, personal fees from Guidepoint Global, personal fees from Haymarket, personal fees from HealthStar, personal fees from Huron Cosulting, personal fees from Incite, personal fees from Inthought, personal fees from IntraMed (Forest), personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, personal fees from LEK, personal fees from McKinsey, personal fees from Medical Knowledge, personal fees from Medimmune, personal fees from Methodist Health System, Dallas, personal fees from Navigant, personal fees from NCI Consulting, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Nuvis, personal fees from Pearl, personal fees from Penn Technology, personal fees from Pfizer, personal fees from PlanningShop, personal fees from Prescott, personal fees from Pro Ed Comm, personal fees from ProiMed, personal fees from PSL FirstWord, personal fees from Pulmatrix, personal fees from Quadrant, personal fees from Qwessential, personal fees from Regeneron, personal fees from Saatchi and Saatchi, personal fees from Schlesinger Associates, personal fees from Strategic North, personal fees from Synapse, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Theron, personal fees from WebMD, grants from NHLBI, grants from Nebraska DHHS, grants from Otsuka, grants from Pfizer, grants from GlaxoSmithKline, grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from Nycomed, grants from Astra-Zeneca, grants from Centocor, grants from Almirall, outside the submitted work.

Funding

Funding provided by VA RR & D (1I01RX000604) and NIH (1R01AG034995, P20GM109090, 1R01HD090333).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

Eric Pisciotta, John McCamley, Shane Wurdeman, Iraklis Pipinos, Jason Johanning, Sara Myers, and Jenna Yentes, declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Brass EP, Hiatt WR, Green S. Skeletal muscle metabolic changes in peripheral arterial disease contribute to exercise intolerance: a point-counterpoint discussion. Vasc. Med. 2004;9:293–301. doi: 10.1191/1358863x04vm572ra. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1358863x04vm572ra. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saey D, Côté CH, Mador MJ, Laviolette L, Leblanc P, Jobin J, et al. Assessment of muscle fatigue during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:62–71. doi: 10.1002/mus.20541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mus.20541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott MM, Hoff F, Ferrucci L, Pearce WH, Guralnik JM, Tian L, et al. Lower extremity ischemia, calf skeletal muscle characteristics, and functional impairment in peripheral arterial disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007;55:400–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01092.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagnon P, Maltais F, Bouyer L, Ribeiro F, Coats V, Brouillard C, et al. Distal leg muscle function in patients with COPD. COPD. 2013;10:235–242. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.719047. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2012.719047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roig M, Eng JJ, MacIntyre DL, Road JD, Reid WD. Deficits in muscle strength, mass quality, and mobility in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2011;31:120–124. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181f68ae4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181f68ae4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regensteiner JG, Wolfel EE, Brass EP, Carry MR, Ringel SP, Hargarten ME, et al. Chronic changes in skeletal muscle histology and function in peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 1993;87:413–421. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.87.2.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koutakis P, Johanning JM, Haynatzki GR, Myers SA, Stergiou N, Longo GM, et al. Abnormal joint powers before and after the onset of claudication symptoms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010;52:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wurdeman SR, Koutakis P, Myers SA, Johanning JM, Pipinos II, Stergiou N. Patients with peripheral arterial disease exhibit reduced joint powers compared to velocity-matched controls. Gait Posture. 2012;36:506–509. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.05.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott-Pandorf MM, Stergiou N, Johanning JM, Robinson L, Lynch TG, Pipinos II. Peripheral arterial disease affects ground reaction forces during walking. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007;46:491–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celis R, Pipinos II, Scott-Pandorf MM, Myers SA, Stergiou N, Johanning JM. Peripheral arterial disease affects kinematics during walking. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009;49:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yentes JM, Sayles H, Meza J, Mannino DM, Rennard SI, Stergiou N. Walking abnormalities are associated with COPD: an investigation of the NHANES III dataset. Respir. Med. 2011;105:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.06.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacIntyre NR. Mechanisms of functional loss in patients with chronic lung disease. Respir. Care. 2008;53:1177–1184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiatt WR, Armstrong EJ, Larson CJ, Brass EP. Pathogenesis of the limb manifestations and exercise limitations in peripheral artery disease. Circ. Res. 2015;116:1527–1539. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303566. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Austin KG, Mengelkoch L, Hansen J, Shahady E, Sirithienthad P, Panton L. Comparison of oxygenation in peripheral muscle during submaximal aerobic exercise, in persons with COPD and healthy, matched-control persons. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2006;1:467–475. doi: 10.2147/copd.2006.1.4.467. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/copd.2006.1.4.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen AH, Childress DS, Miff SC, Gard SA, Mesplay KP. The human ankle during walking: implications for design of biomimetic ankle prostheses. J. Biomech. 2004;37:1467–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.01.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Statistics V. Preliminary data for 2010. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2012;60:1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vestbo J. COPD: definition and phenotypes. Clin. Chest Med. 2014;35:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Donnell DE, Ora J, Webb KA, Laveneziana P, Jensen D. Mechanisms of activity-related dyspnea in pulmonary diseases. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009;167:116–132. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.01.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Rio F, Lores V, Mediano O, Rojo B, Hernanz A, López-Collazo E, et al. Daily physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is mainly associated with dynamic hyperinflation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009;180:506–512. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1873OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200812-1873OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson GC, Müllerova H, Locantore N, Hurst JR, Calverley PMA, Vestbo J, et al. Factors associated with change in exacerbation frequency in COPD. Respir. Res. 2013;14:79. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-79. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-14-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Aymerich J, Félez MA, Escarrabill J, Marrades RM, Morera J, Elosua R, et al. Physical activity and its determinants in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1667–1673. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142378.98039.58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000142378.98039.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosker HR, van Mameren H, van Dijk PJ, Engelen MPKJ, van der Vusse GJ, Wouters EFM, et al. Skeletal muscle fibre-type shifting and metabolic profile in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2002;19:617–625. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00762001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00762001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MD, Cutaia M. A novel approach to measuring activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: using 2 activity monitors to classify daily activity. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2010;30:186–194. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181d0c191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181d0c191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karpman C, DePew ZS, LeBrasseur NK, Novotny PJ, Benzo RP. Determinants of gait speed in COPD. Chest. 2014;146:104–110. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahousse L, Verlinden VJa, van der Geest JN, Joos GF, Hofman A, Stricker BHC, et al. Gait patterns in COPD: the rotterdam study. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;46:88–95. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00213214. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00213214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saey D, Debigaré R, LeBlanc P, Mador MJ, Côté CH, Jobin J, et al. Gait characteristics in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:425–430. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-856OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2150131915577207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yentes JM, Rennard SI, Blanke D, Stergiou N. Patients with COPD walk with a more periodic step width pattern as compared to healthy controls. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014;189:A2643. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butcher SJ, Meshke JM, Sheppard S. Reductions in functional balance, coordination, and mobility measures among patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. 2004;24:274–280. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200407000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yentes JM, Schmid KK, Blanke D, Romberger DJ, Rennard SI, Stergiou N. Gait mechanics in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir. Res. 2015;16:31. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0187-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0187-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Z, Swanson SA, Nella AA, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: part 2. Oxidative stress, neuropathy, and shift in muscle fiber type. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2008;42:101–112. doi: 10.1177/1538574408315995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1538574408315995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pipinos II, Judge AR, Selsby JT, Zhu Zhen, Swanson SA, Nella AA, et al. The myopathy of peripheral arterial occlusive disease: part 1. Functional and histomorphological changes and evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2008;41:481–489. doi: 10.1177/1538574407311106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1538574407311106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makris K, Nella A, Zhu Z, Swanson S, Casale G, Gutti TL, et al. Mitochondriopathy of peripheral arterial disease. Vascular. 2007;15:336–343. doi: 10.2310/6670.2007.00054. http://dx.doi.org/10.2310/6670.2007.00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDermott MM. Lower extremity manifestations of peripheral artery disease: the pathophysiologic and functional implications of leg ischemia. Circ. Res. 2015;116:1540–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303517. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puente-Maestu L, Pérez-Parra J, Godoy R, Moreno N, Tejedor A, Gonzaiez-Aragoneses F, et al. Abnormal mitochondrial function in locomotor and respiratory muscles of COPD patients. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;33:1045–1052. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00112408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00112408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer A, Zoll J, Charles AL, Charloux A, de Blay F, Diemunsch P, et al. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction during chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: central actor and therapeutic target. Exp. Physiol. 2013;98:1063–1078. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Afaq A, Patel JH, Gardner AW, Hennebry TA. Predictors of change in walking distance in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing endovascular intervention. Clin. Cardiol. 2009;32:7–11. doi: 10.1002/clc.20553. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/clc.20553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardner AW, Killewich LA. Lack of functional benefits following infrainguinal bypass in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. Vasc. Med. 2001;6:9–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/135886301668561166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saey D, Debigaré R, LeBlanc P, Jeffery Mador M, Côté CH, Jobin J, et al. Contractile leg fatigue after cycle exercise: a factor limiting exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:425–430. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200208-856OC. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200208-856OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quality Statement 3: Supervised Exercise Programms, NICE, 2014. [Accessed 11 June 2017]; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs52/chapter/Quality-statement-3-Supervised-exercise-programmes.

- 40.A Structured Exercise Programme to Increase Pain-free Walking and Improve Quality of Life by Integrating Peripheral Arterial Disease Patients into an Established Cardiac Rehabilitation Programme, NICE, 2016. [Accessed 22 April 2017]; https://www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/a-structured-exercise-programme-to-increase-pain-free-walking-and-improve-quality-of-life-by-integrating-peripheral-arterial-disease-patients-into-an-established-cardiac-rehabilitation-programme.

- 41.PADex, Manchester’s Disease Specific Supervised Exercise Programme for Patients with Intermittent Claudication, NICE, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease GOLD executive summary. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis RB, Õunpuu S, Tyburski D, Gage JR. A gait analysis data collection and reduction technique. Hum. Mov. Sci. 1991;10:575–587. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-9457(91)90046-Z. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson KM. Fitting of mathematical functions to biomechanical data. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME-26. 1979:122–124. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1979.326551. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TBME.1979.326551. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Winter DA. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement. Wiley; New York: 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470549148 2nd: 386. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen SJ, Pipinos I, Johanning J, Radovic M, Huisinga JM, Myers SA, et al. Bilateral claudication results in alterations in the gait biomechanics at the hip and ankle joints. J. Biomech. 2008;41:2506–2514. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.05.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDermott MM, Criqui MH, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, Liu K, Pearce WH, et al. Leg strength in peripheral arterial disease: associations with disease severity and lower-extremity performance. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004;39:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2003.08.038. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2003.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Câmara LC, Ritti-Dias RM, Menêses AL, D’Andréa Greve JM, Filho WJ, Santarém JM, et al. Isokinetic strength and endurance in proximal and distal muscles in patients with peripheral artery disease. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2012;26:1114–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2012.03.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.avsg.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pandy MG, Andriacchi TP. Muscle and joint function in human locomotion. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2010;12:401–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-070909-105259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farris DJ, Sawicki GS. The mechanics and energetics of human walking and running: a joint level perspective. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2011:9. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pipinos II, Sharov VG, Shepard AD, Anagnostopoulos PV, Katsamouris A, Todor A, et al. Abnormal mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003;38:827–832. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00602-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0741-5214(03)00602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deschênes D, Pepin V, Saey D, LeBlanc P, Maltais F. Locus of symptom limitation and exercise response to bronchodilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2008;28:208–214. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000320074.73846.3b. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.HCR.0000320074.73846.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scherer SA, Bainbridge JS, Hiatt WR, Regensteiner JG. Gait characteristics of patients with claudication. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998;79:529–531. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90067-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCully K, Leiper C, Sanders T, Griffin E. The effects of peripheral vascular disease on gait. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1999;54:B291–4. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.7.b291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/54.7.B291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bishop DJ, Granata C, Eynon N. Can we optimise the exercise training prescription to maximise improvements in mitochondria function and content? Biochim. Biophys. Acta – Gen. Subj. 2014;1840:1266–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]