Abstract

Background

Women in medicine may feel pressure to choose between the competing demands of career goals and being a dedicated spouse and parent.

Objective

The purpose of this survey study is to report on the current opinions of female dermatologists with regard to family planning, maternity leave, and career success.

Methods

We surveyed 183 members of the Women’s Dermatologic Society using a 13-question survey that was approved for distribution by the institutional review board committee of the University of Connecticut Health Center.

Results

We found that women were most likely to have children while they were residents (51%), despite the fact that residents were more likely to report barriers to childbearing at this career stage. These barriers included length of maternity leave, appearing less committed to residency responsibilities compared with peers, and inadequate time and privacy to breast feed. Strategies to achieve a work-life balance included hiring in-home help and working part-time. Of note, many women commented on the need for more family planning resources at work.

Conclusion

Thought should be given to future administrative strategies that can lessen the burden of parents who are dermatologists and have academic ambitions.

Keywords: work-life balance, parenting, childbearing, maternity leave, family planning

Introduction

Among the various specialties, dermatologists are traditionally known as physicians who are the most satisfied and more than half of those surveyed report that they are content with their work-life balance (Shanafelt et al., 2012). However, recent data from the Mayo Clinic found that dermatologists had the greatest increase in self-reported professional burnout among all specialties from 32% in 2011 to 57% in 2014 (Shanafelt et al., 2015). Although common stressors have been identified that put all physicians at a greater risk for burnout and emotional exhaustion (e.g., demanding and increasing workloads, loss of autonomy over work, balancing family demands [Shanafelt et al., 2015]), opinions on work-life balance and specifically those of female physicians have not been well investigated. Previous authors have shown that women are more dissatisfied than men with career advancement opportunities and less likely to hold leadership positions (Rizvi et al., 2012, Sadeghpour et al., 2012, Strong et al., 2013). In fact, only 19% of permanent dermatology department chairs are women (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2014). Despite these findings, the intricacies of family and career planning are infrequently discussed.

Our survey study explores issues related to childbearing, maternity leave, and career satisfaction among female dermatologists. Although statistically significant findings were limited due to response rate, our research provides qualitative insight into the current opinions of female dermatologists on work-life balance.

Methods

A 13-question survey was approved by the institutional review board committee of the University of Connecticut Health Center (IRB# 16-200-2) for email distribution to 1200 members of the Women’s Dermatologic Society. The survey was displayed using a third-party online survey collection site. The authors had full access to the survey responses including individual responses. Questions included general demographic information (age, marital status, number of children) as well as specific questions about work and family life.

Results

Respondents

Of the 1200 female dermatologists who were surveyed, 183 participated in the survey (response rate, 15.3%). Four surveys were excluded from the study because the respondents did not complete the survey beyond the first or second questions. Of the 179 responses that were included, 56% of women had children and 44% did not, and 78.8% were married and 21.2% were not. The age group distribution of the respondents was 26 to 35 years (52%), 36 to 45 years (21.8%), 46 to 55 years (12.3%), 56 to 65 years (9.5%), 66 to 75 years (3.9%), and 75 + years (0.5%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of respondents

| Age range (years) | With children (n = 102) | Without children (n = 77) | Total (n = 179) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26-35 | 35 | 58 | 93 |

| 36-45 | 28 | 11 | 39 |

| 46-55 | 19 | 3 | 22 |

| 56-65 | 13 | 4 | 17 |

| 66-75 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| > 75 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Childbearing

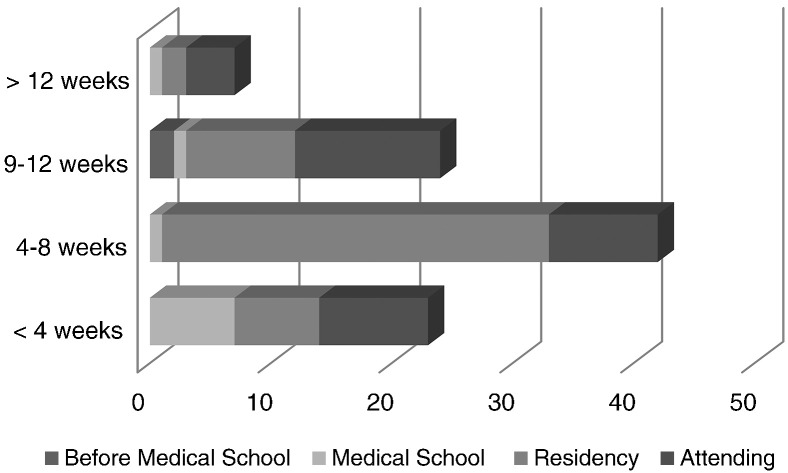

Of the women who had children, the responses to the question “At what point in your training did you have your first child?” showed that 2% had their first child prior to enrolling in medical school, 11% during their medical school years, 51% as a resident, and 36% as an attending physician (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Length of maternity leave versus career stage.

Maternity leave

Responses to the question “Were you able to negotiate the length of your maternity leave?” showed that 41% of respondents (n = 97) negotiated their maternity leave including 64.3% of attending physicians and 33.3% of residents. When asked “How much time did you take for maternity leave?”, of the 96 women who answered the question, 25% took less than 4 weeks, 42.7% took 4 to 8 weeks, 25% took 9 to 12 weeks, and 7.3% were able to take more than 12 weeks of maternity leave.

Support of colleagues

In response to the question “Were your colleagues supportive of your maternity leave?”, 81% of women (n = 92) reported they received support from their coworkers during maternity leave.

Work-life satisfaction

Forty percent of women with children (n = 91) answered yes in response to the question “Did you feel you missed out on your child(ren)’s milestones?”

Career goals

When asked “Did you sacrifice your ideal job because of your spouse’s career choices?”, 20.2% of women with children (n = 89) reported that they had but 9.8% of women who did not have children (n = 51) reported likewise. Of the 69 women without children who responded to the question “Did you choose success in your career rather than a family?”, 36% reported that they did.

Discussion

Many female physicians have become successful clinicians, researchers, and parents despite the unique demands of the medical profession. Our goal was to explore the satisfaction of female dermatologists with their experiences in navigating career goals and family planning and identify current perceived barriers to personal success. Of the respondents who did not have children, 36% reported that they chose career success over starting a family and 31.6% specifically commented that they still planned to have children later in life. Although we did not specifically ask for the reasons why women chose not to have children, Willet et al. (2010) reported that the most concerning barrier for female physicians was the potential need to extend their residency training if they became pregnant, causing them to be significantly less likely to have a child during residency training than male residents.

The free responses in our survey confirmed that the barriers to childbearing were perceived to be especially high during residency. These barriers include the perception that women who have children during residency training are less committed to their jobs than male peers and concerns of overburdening fellow residents. One woman stated that “[t]here is no way to be an excellent resident and study as I should if I had children during residency.” Another woman commented that “[o]ther residents have to work twice as hard if someone has a baby so there is ill-disguised animosity when people start having kids.” Some programs were described as outwardly unsupportive and one of our 180 respondents indicated that all her male co-residents had babies yet she, as a female, was discouraged from doing the same. However, it is interesting to note that despite these issues, we found that a slight majority of female dermatologists had their first child during residency (51%). We acknowledge that many resident programs do work hard to accommodate family planning and the comments reported above do not represent all dermatology programs.

Another challenge of childbearing is maternity leave. Gunn et al. (2014) surveyed women in academic leadership positions who were responsible to mentor younger female physicians and found that the majority did not know, or incorrectly cited, their institution’s maternity leave policies. A lack of discussion and opportunity to advocate may be contributing to the dissatisfaction that our respondents reported with the time allotted for maternity leave. Additionally, although the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 allows for 12 weeks of unpaid leave for any employee who has completed a full year of employment, the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) guidelines allow for a maximum of 14 weeks away from the program over 3 years of residency (American Board of Dermatology, 2016, U.S. Department of Labor, 2016). Time away includes vacation and sick time as well as maternity leave.

If a resident exceeds this maximum amount of time, they are at risk of extending their residency and perhaps delaying sitting for the board examination (American Board of Dermatology, 2016, Peart et al., 2015). This creates a potential conflict for residents who desire a longer bonding period with their baby, more time to recover from a complicated pregnancy, or who may need additional time for other reasons. One resident reported, “I was only given 6 weeks for maternity leave, in comparison to the 3 months allotted for most working women; this discrepancy deeply bothered me and was very disheartening, as medical professionals should understand best the needs of a newborn baby and mom.”

In 2001, the Women in Dermatology Society called for the ABD to increase scheduling flexibility due to the growing number of female dermatologists and stated that having children during residency should be an “anticipated event,” especially because 62% of dermatology residents are women (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2015, Peart et al., 2015). Unfortunately, administrative challenges including finding an appropriate balance between flexibility for leave, sufficient coverage of the practice, and adequate and uniform training, are quite challenging and complex. Although ABD guidelines have not yet changed, by law, women do have the option to extend their residency to allow for a longer maternity leave. The ABD has even allowed these residents to sit for their board examinations without delaying graduation, especially when the program director rates their performance as above average (Peart et al., 2015).

More women now also choose to breastfeed after childbirth, which provides another challenge for the working dermatologist (Allen et al., 2013, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Sattari et al., 2010, Sattari et al., 2016 found that only two-thirds of female physicians who intended to breastfeed for 1 year could reach this goal. The others were deterred by inadequate time at work to breastfeed or pump, leading to an inadequate milk supply. In 2016, Sattari et al. (2010) found that among 72 internal medicine physicians who intended to breastfeed their children, only 40% were able to do so for 12 months. While our survey did not directly explore breastfeeding practices among female dermatologists, respondents reported difficulties in stepping away from their clinic to pump breast milk and finding a private location to do so. One physician commented, “I have pumped in so many gross hospital bathrooms; it is seriously troubling.” Fortunately, the need to support breastfeeding has gained recognition in many workplaces including hospitals. Lactation programs and policy improvements can lead to significantly higher breastfeeding rates among hospital employees (Spatz et al., 2014).

Overall, many women in our survey did report excellent childbearing experiences while maintaining the ability to pursue a successful clinical career. One of the critical factors that was necessary to achieve this balance was an increased flexibility in certain areas of life such as hiring help or working part-time. Many women identified supportive spouses as vital to their work-life balance and some even reported that their partners forewent their own career goals to raise the children.

In the clinic, women especially emphasized the importance of supportive mentors and colleagues. Our survey found that 81% of respondents felt supported by their colleagues during their pregnancy. One resident commented on her experience, “I did not sleep the night before I was going to tell my program director I was pregnant. I was nervous he would be angry or upset at me. Nothing could be further from the truth… He instantly beamed the biggest smile I’ve seen, hugged me, and said, ‘this is the best news I’ve heard and I am so thrilled for you!' He continued, ‘This will make you a better physician … and a better person. You will understand pediatric dermatology and how to empathize with families in a way residency will not be able to teach you, and your maternity leave will be an education in itself.'” Studies have shown that a healthy work-life balance is positively associated with mentorship as well as an environment that focuses on the development of female leaders (Pololi et al., 2013, Zhuge et al., 2011). Medical cultures that adapt to support women who strive to be both caring mothers and successful physicians significantly improve work-to-family conflict (Westring et al., 2014).

Although we intentionally focused on the experiences of female dermatologists, future exploration of male dermatologists’ perceptions of work-life balance and parenting would also be insightful. Additionally, the limitations of this study include those that are inherent to a survey. The response rate was low (15.3%) and limited the statistical significance of the findings. Responses were also subject to responder bias. Although the age group of 26 to 35 years was represented the most in this study (52%), the number of women with and without children who responded was fairly equal (56% vs. 44%). It is also unclear whether institutions and cultures across the United States were equally represented.

Conclusions

Although some female physicians have been able to accomplish both professional and personal goals with high satisfaction, others have struggled with the competing demands of career goals and family life. Our survey questioned female dermatologists on their personal experiences with parenting, maternity leave, and career success. The majority of respondents with children had their first child during residency training despite the fact that barriers were perceived as the highest at this time.

In our survey, women commented that the length of maternity leave, inadequate time and logistics for breastfeeding, and the lack of support from their colleagues and superiors were major contributors to stressful work environments. Women found ways to lessen the competing demands of work and family life by working part-time, hiring in-home help, or relying on supportive family members. The development of new strategies to better support issues of childbearing and maternity leave, especially in the design of residency programs, may be advantageous to further provide female dermatologists with the flexibility they need to enjoy their families, maintain their personal health, and continue pursuing their career goals in medicine.

Acknowledgments

It is fitting that an article on work-life balance and parenting should find itself in an issue dedicated to Dr. Jane Grant-Kels. I have had the pleasure of knowing Dr. Grant-Kels for more than 25 years as I first met her when I was in medical school. Back in the early 1980s, the culture of medicine was quite different and Dr. Grant-Kels was unique. She integrated anecdotes about her children and parenting into her lectures and her daily work life. She seamlessly managed to be an involved, mother-of-two, female department head, an expert in dermatology, and a dermatopathologist. She provided a unique and refreshing example of a woman who could accomplish a great deal professionally while maintaining a nurturing motherly persona that she was not afraid to embrace.

I subsequently worked in academic dermatology, mainly because of Dr. Grant-Kels, and have been a colleague in her department for many years. She mentored me through two pregnancies and two adoptions and ensured that my children and my family never had to take a backseat to my career. I realize that not all women (or men) have been given that opportunity especially in the medical field. It is important that we continue to improve working conditions and mentor those who choose to have a family. In an era where medicine is more complicated than ever and physician burnout is increasing, an emphasis on a healthy work-life balance benefits all of us. Thank you, Dr. Grant-Kels, for modeling this before it became popular!

References

- Allen J.A., Li R., Scanlon K.S., Perrine C.G., Chen J., Odom E. Vol. 62. 2013. Progress in increasing breastfeeding and reducing racial/ethnic differences – United States, 2000-2008 births; pp. 77–80. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Board of Dermatology Guidelines for determining adequacy of clinical training [Internet] 2016. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/residency-training/leave-of-absence-guidelines.aspx [cited 2016 February 22]. Available from:

- Association of American Medical Colleges The state of women in academic medicine: The pipeline and pathways to leadership [Internet] 2014. https://www.aamc.org/members/gwims/statistics/ [cited 2015 January 12]. Available from:

- Association of American Medical Colleges Number of active residents, by type of medical school, GME specialty, and gender [Internet] 2015. https://www.aamc.org/data/448482/b3table.html [cited 2015 January 12]. Available from:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Breastfeeding report card [Internet] 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/reportcard.htm [cited 2016 January 5]. Available from:

- Gunn C.M., Freund K.M., Kaplan S.A., Raj A., Carr P.L. Knowledge and perceptions of family leave policies among female faculty in academic medicine. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peart J.M., Klein R.S., Pappas-Taffer L., Lipoff J.B. Parental leave in dermatology residency: Ethical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:707–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pololi L.H., Civian J.T., Brennan R.T., Dottolo A.L., Krupat E. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: Gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi R., Raymer L., Kunik M., Fisher J. Facets of career satisfaction for women physicians in the United States: A systematic review. Women Health. 2012;52(4):403–421. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.674092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghpour M., Bernstein I., Ko C., Jacove H. Role of sex in academic dermatology: Results from a national survey. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:809–814. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattari M., Levine D., Betram A., Serwint J.R. Breastfeeding intentions of female physicians. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:297–302. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2009.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattari M., Serwint J.R., Shuster J.J., Levine D.M. Infant-feeding intentions and practices of internal medicine physicians. Breastfeed Med. 2016;11:173–179. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2015.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T.D., Boone S., Tan L., Dyrbye L.N., Sotile W., Satele D. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt T.D., Hasan O., Dyrbye L.N., Sinsky C., Satele D., Sloan J. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general U.S. working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatz D.L., Kim G.S., Froh E.B. Outcomes of a hospital-based employee lactation program. Breastfeed Med. 2014;9(10):510–514. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong E.A., De Castro R., Sambuco D., Stewart A., Ubel P.A., Griffith K.A. Work-life balance in academic medicine: Narratives of physician-researchers and their mentors. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1596–1603. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2521-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division. Family and Medical Leave Act [Internet] 2016. http://www.dol.gov/whd/fmla/ [cited 2016 February 22]. Available from:

- Westring A.F., Speck R.M., Sammel M.D., Scott P., Conant E.F., Tuton L.W. Culture matters: The pivotal role of culture for women’s careers in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2014;89:658–663. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willet L.L., Wellons M.F., Hartig J.R., Roenigk L., Panda M., Dearinger A.T. Do women residents delay childbearing due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85:640–646. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuge Y., Kaufman J., Simeone D.M., Chen H., Velazquez O.C. Is there still a glass ceiling for women in academic surgery? Ann Surg. 2011;253:637–643. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182111120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]