Abstract

Despite divergent evolutionary origins, the organization of olfactory systems is remarkably similar across phyla. In both insects and mammals, sensory input from receptor cells is initially processed in synaptically dense regions of neuropil called glomeruli, where neural activity is shaped by local inhibition and centrifugal neuromodulation prior to being sent to higher order brain areas by projection neurons. Here we review both similarities and several key differences in the neuroanatomy of the olfactory system in honey bees, mice and humans, using a combination of literature review and new primary data. We have focused on the chemical identity and the innervation patterns of neuromodulatory inputs in the primary olfactory system. Our findings show that serotonergic fibers are similarly distributed across glomeruli in all three species. Octopaminergic/tyraminergic fibers in the honey bee also have a similar distribution, and possibly a similar function, to noradrenergic fibers in the mammalian OBs. However, preliminary evidence suggests that human OB may be relatively less organized than its counterparts in honey bee and mouse.

Keywords: human olfaction, honey bee, antennal lobe, noradrenaline, octopamine, serotonin

Introduction

The olfactory bulb (OB) and antennal lobe (AL) are the initial areas of olfactory processing in mammals and insects, respectively (Hildebrand and Shepherd 1997). In both structures sensory inputs arrive via axons of olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) whose cell bodies are located in peripheral structures (olfactory epithelium, antennae) (Doty 2012; Feinstein and Mombaerts 2004; Galizia and Rossler 2010; Halász and Shepherd 1983; Huart et al. 2013; Maresh et al. 2008; Nagayama et al. 2014; Patel and Pinto 2014; Schmuker et al. 2011). ORNs typically express one olfactory receptor (OR) that gives rise to the range of odors that an ORN responds to (Buck and Axel 1991; Vosshall et al. 2000; Zhang and Firestein 2002). Axons from neurons expressing the same OR converge to the same glomerulus, a region of neuropil that coarsely represents one “channel” of sensory input. The molecular mechanism of signal transduction of mammalian ORs is different from insects, which express the unique OR with a second OR that is common across all ORNs (Kaupp 2010; Missbach et al. 2014; Silbering and Benton 2010; Vosshall and Hansson 2011). However, olfactory coding in ORNs in both phyla still occurs through combinatorial coding using somewhat broadly tuned ORs.

Several principal projection neurons (PNs in insects and Mitral/Tufted cells in mammals) typically sample a single glomerulus with their primary dendrites. They project to deeper brain structures while also experiencing both local lateral inhibition as well as feedback and neuromodulation from distant cells providing centrifugal inputs (Shepherd 2003).

While this overall architecture represents a coarse generalization of most animals’ primary olfactory structures, in the following sections we describe in greater detail the species-specific anatomy of these structures and cell types, and highlight both surprising similarities but also key distinctions that potentially make each species’ olfactory system unique. These data provide important comparative information regarding olfactory coding strategies and may assist computational modeling of specific and potentially important features of the olfactory system.

Results

The human OB (Table 1, Figure 1) in a healthy individual is approximately 11 mm long and has a discontinuous glomerular layer concentrated on the rostral and ventral side of the OB where the olfactory nerve enters (Bhatnagar et al. 1987). Its cytoarchitecture was first described by Camillo Golgi (Golgi 1875), reproduced in (Sarnat and Yu 2016), and further studied and discussed by Cajal (Ramon y Cajal 1911). Its neurochemical composition has been described in several publications (Baker 1986; Doty 2012; Huart et al. 2013; Maresh et al. 2008; Ohm et al. 1988a; Ohm et al. 1988b; Ohm et al. 1991; Ohm et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1993; Smith et al. 1991). The human OB has the typical layered organization of a mammalian OB (Figure 1), with each glomerulus associated with a stereotypical group of neurons involved in the processing of olfactory information (Bhatnagar et al. 1987; Golgi 1875; Maresh et al. 2008). The adult human OB has a less strictly layered organization compared with non-human primates, other mammals (Smith et al., 1991) and even to humans during prenatal development (Humphrey 1940; Kharlamova et al. 2015; Sarnat and Yu 2016).

Table 1.

The composition of the olfactory glomerular module in human, mouse, and honey bee

| Number of Odorant Receptors (OR) | Number of Glomeruli | Number of Output Neurons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GD: glomerular diameter | |||

|

| |||

| Human | ~350 (1) | ~5,500 (4) | ~8 (7)? Mitral and ? |

| Olfactory epithelium | Average GD 60 μm | Tufted | |

| Olfactory bulb | 16 glomeruli/1 OR | cells/glomerulus | |

|

| |||

| Mouse | ~1100 (2) | ~3700 (5) glomeruli | ~8 (8) Mitral and 4.5 |

| Olfactory epithelium | GD between 50–100 μm | Tufted | |

| Olfactory bulb | 2–3 glomeruli per OR | cells/glomerulus | |

|

| |||

| Honey bee | ~170 (3) | ~160–170 (6) | ~5–6 (6) Projection |

| Antenna | GD between 20–65μm | Neurons/glomerulus | |

| Antennal lobe | 1 glomerulus per OR | ||

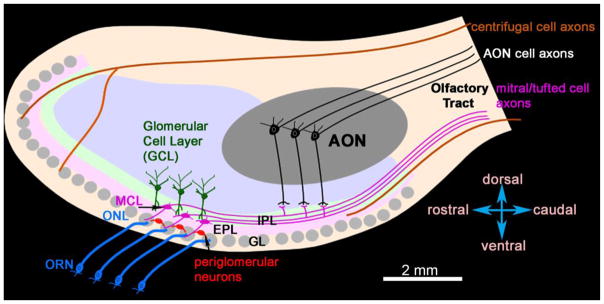

Figure 1. Schematic of a human olfactory bulb (OB) (sagittal view).

The description of the cell layers and size of the human OB are derived from Bhatnagar et al. 1987, Golgi, 1885, and Ramon y Cajal, 1911. The olfactory nerve layer (ONL), where axons of Olfactory Receptor Neurons (ORN) enter and terminate in the glomeruli that are located in the Glomerular Layer (GL). Periglomerular cells are neurons that arborize in the glomerulus and/or interconnect the glomeruli in GL. Mitral cells are located in the Mitral Cell Layer (MCL). Together with tufted cells (not shown here) mitral cells extend dendrites into the GL and External Plexiform Layer (EPL) and project axons into the Internal Plexiform Layer (IPL). The axons of the mitral and tufted cells leave the OB via the ventrolateral part of the olfactory tract. Granule cells are in the Granule Cell Layer (GCL); they lack axons, and/their dendrites are in EPL, IPL, and GCL. The Anterior Olfactory Nucleus is in the OB in human, and its pyramidal cells have their dendrites in the IPL and GCL. There are axons from centrifugal neurons that arrive at the OB via OT, the exact organization of their fibers in the OT is not well studied in human. The axons of centrifugal neurons end in all layers of the OB. Scale bar: 2mm

The OB in the adult mouse (Figure 2, Table 1) is up to 3mm long (Richard et al. 2010; Rodriguez-Gil et al. 2015). It also has a layered organization with structural organization similar to the human OB (Imai 2014; Maresh et al. 2008; Whitman and Greer 2009).

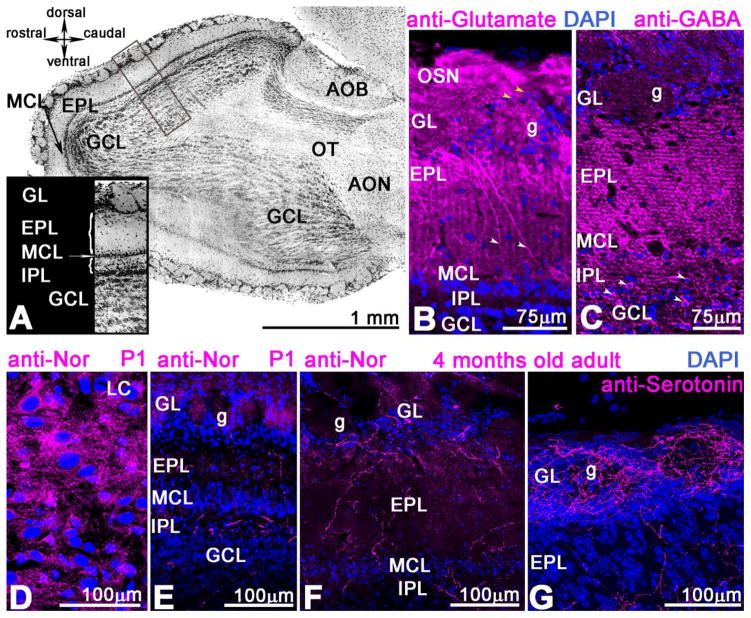

Figure 2. Cytoarchitecture of mouse OB.

A. Sagittal view of the adult OB with all cells labeled with DAPI (nuclear marker). The DAPI is blue in B–G. The insert shows the cellular organization of the bulb including cell layers and neuropil containing axons. The following layers are noted: the ORN from olfactory epithelium branches into the olfactory glomerular layer (GL) surrounded by local interneurons; periglomerular (PG) cells; EPL- external plexiform layer with axons and dendrites of Mitral and Tufted cells; MCL- mitral cell layer; IPL- internal plexiform layer, GCL- granule cell layer. B. The anti-glutamate immunostained ORNs terminating in the glomeruli and periglomerular interneurons (yellow arrowhead); Mitral cells stained with anti-glutamate have long primary dendrites in the EPL (white arrowhead) and glomerulus (g). The anti-glutamate antibody does not label the mitral cell axons in the IPL. C. Anti-GABA mostly labels the glomerular cell bodies (white arrow) in the GCL and is highly dense in the EPL; a few PG cells that surround glomerulus (g) express GABA as well. D. The noradrenaline-containing cell bodies are in the locus coeruleus of newly born mice (P1); they send their axons throughout the brain including the OB (E). These fibers are highly distributed in the GCL, but somewhat less in EPL and between glomeruli (g). F. Noradrenaline in the 6 months old adult mouse is less dense in the IPL layer and distributed between glomeruli (g). G. In the 6 months old mouse the serotonin fibers originating from cell bodies located in the raphe nucleus are abundant in the OB, especially in the glomeruli. Scale bar: A=1mm, B C =75μm; D–G=100 μm

The honey bee AL (Figure 3, Table 1) is functionally analogous to the mammalian OB. Early comparative studies in the AL of other insects (locust and moth) noted in great details the similarities and differences in the anatomy of early olfactory processing compared with mammals (Hildebrand and Shepherd 1997). In (Imai 2014) the functional similarities and differences between the principal cells of the fruit fly AL and mouse OB were discussed, and the total neuronal composition of the fruit fly AL was recently published by (Berck et al. 2016). Honey bees have a highly organized and efficient AL neuronal network (Brill et al. 2013; Carcaud et al. 2015; Kropf et al. 2014; Menzel and Giurfa 1999; Nishino et al. 2009; Rybak 2012; Sachse and Galizia 2003; Smith 2012). Honey bees have a broad spectrum of complex olfactory learning behaviors that can be studied under laboratory conditions, in which in vivo neuroimaging, molecular biology, and electrophysiological recording can be coupled with behavioral assays (Carcaud et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2015; Daly et al. 2004a; Daly et al. 2004b; Fernandez et al. 2009; Krofczik et al. 2008; Locatelli et al. 2012; Schmuker et al. 2011; Szyszka et al. 2014; Yamagata et al. 2009). The discovery of modulatory VUM neurons in the honey bee by (Hammer 1993; Hammer and Menzel 1998) has opened the door to an understanding of how olfactory neuromodulation might work in other species as well (Fellous and Linster 1998; Linster and Hasselmo 1997; Linster and Smith 1997; Montague 2016).

Figure 3. Biogenic amines in honey bee AL.

A. Schematic of pathways in the antennal lobe (AL) and brain. B. The synaptic marker synapsin defines glomerular and aglomerular neuropils in the antennal lobe. C. Sensory information from axons of olfactory receptor neurons (ORN) enters via the T1–T4 tracts of the antennal nerve from the antenna and divides each glomerulus into two functionally distinctive areas: cortex (ORN labeled with tracer neurobiotin ends in the cortex, D) and core (absence of ORN ends D). C, E. The uPNs, AL output neurons, have dendrites in both cortex and core and connect AL with a calyx of mushroom bodies via two major tracts: l-and m-APT. F. Anti-GABA is in whole glomerulus. G. Local Neurons (LN) express anti-GABA and consist of two types: LN homo and LN het. The aglomerular neuropil of AL is characterized by a high density of ORN axons (C), uPNs, ml-APT1,2 mPNs (A), LNs (G). Both glomerular and algomerular neuropil are necessary for odor computation; while the glomerulus is the functional unit that receives ORN input and processes the odor via uPNs to higher brain areas, the aglomerular neuropil is the major area where the AL neurons receive the global modulatory signal octopaminergic (A,H), serotoninergic (C,I) and dopaminergic (J,K), despite a lack of synaptic machinery. Each monoamine fibers are distributed differently in glomerulus: octopamine in cortex area (H,L), serotonin in whole glomerulus (I,L), dopamine in fibers between glomerulus (J,K,L). Scale bar: B=75μm; D–F, H–J=10 μm; K=100 μm.

Olfactory Receptor Neurons

The first layer in the human OB is composed of axons of the olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs, also “olfactory sensory neurons”) that enter the OB and are ensheathed by glial cells (Figure 1, Table 1). Each ORN expresses only one type of odorant receptor (OR), and there are 350–400 ORs identified in the human genome (Glusman et al. 2001; Young et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2007). Each ORN type targets ~16 glomeruli (Maresh et al. 2008).

In mice, by contrast, there are ~1200 ORs (Zhang et al, 2007), but each ORN sends its axons to only 2–3 glomeruli per hemibulb (Table 1). Thus, there are a greater number of distinct sensors, but fewer processing channels per sensor, compared with the human OB. Some of these ORs are exclusively expressed in the vomeronasal organ, a parallel olfactory pathway that targets the accessory olfactory bulb (AOB) and is involved in the detection of non-volatile odorants (Mucignat-Caretta et al. 2012). No structure strictly analogous to the AOB has been identified in the adult human olfactory system (Bhatnagar et al. 1987), however its status during development remains controversial (see review by (Meredith 2001)).

In the honey bee, the olfactory pathway begins with antennae where ORNs have their dendrites and cell bodies, with axons reaching the AL via the antennal nerve (Fig. 3A). The honey bee has approximately 170 olfactory receptor genes (Robertson and Wanner 2006). The sensory information from ORNs enters the AL via the T1–T4 tracts (Fig. 3C). These tracts subdivide the AL into four regions (Abel et al. 2001; Yamagata et al. 2009). Tracts T5 and T6 from the antennal nerve carry mechanosensory fibers to the dorsal lobe and subesophageal ganglion (SEG). There are ORs responsive to volatile odorants as well the ORs that specialize in processing pheromones; ORNs for the latter converge in only few glomeruli and are differentially regulated in the queen, worker bees and drones (Wanner et al. 2007a; Wanner et al. 2007b). Honey bee ORNs have a distinct group of receptors from moths, mosquitoes, and flies, with the exception of the generic AmOr2 receptor, which is required for signal transduction in insects (Robertson and Wanner 2006; Sato et al. 2008). In insects, the OR signaling mechanisms uses an ionotropic receptor that is formed by a complex of a single type of OR with a common (across ORNs) OR co-receptor OR83b, first described in the fruit fly (Larsson et al. 2004; Vosshall and Hansson 2011). Thus, in insects, the odor ligand directly activates an ionotropic receptor, while in mammals it acts via a ligand-gated metabotropic receptor to indirectly activate an ion channel (for a detailed review see (Silbering and Benton 2010)).

Glomeruli

The second layer of the OB is the glomerular layer (Glomerular Layer, GL, Figure 1, Table 1). In rodents, each glomerulus receives projections from ORNs expressing the same OR (Buck and Axel 1991; Mombaerts et al. 1996), although it is unknown if this principle is universal among mammals. The human OB has on average 5500 ± 830 glomeruli (Maresh et al. 2008) in the GL, with each glomerulus containing glutamatergic axons from the ORNs and dendrites of glutamatergic mitral and tufted cells. That ORNs are glutamatergic is well-established in rodents (Berkowicz et al. 1994), but in humans the only evidence for this is the presence of vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT2) in the glomeruli (Maresh et al. 2008). Periglomerular (PG) cells are also located in this layer and express dopamine and GABA (Alizadeh et al. 2015; Hoogland and Huisman 1999; Ohm et al. 1990; Smith et al. 1991).

The mouse OB contains ~3,700 glomeruli (Richard et al. 2010; Rodriguez-Gil et al. 2015). In the mouse, a typical glomerulus is innervated by ~8 mitral cells and ~4.5 tufted cells (Liu et al. 2016) (Table 1). The overall excitatory/inhibitory composition of the neurons associated with each glomerulus has been described extensively (Halász and Shepherd 1983; Mori et al. 1999; Murphy et al. 2005; Schoppa and Urban 2003; Shipley and Ennis 1996). Here we used anti-glutamate antibodies to demonstrate that each glomerulus has glutamatergic ORNs synapsing onto glutamatergic mitral/tufted cell dendrites and periglomerular cells (Fig. 2A, B, insert). These periglomerular cells are glutamate- and GABA-positive (Fig. 2A, B, insert; Fig 2B, C) but some are also known to use dopamine (DA) as a neurotransmitter (Baker 1986). However, there are additional DA cell types located in the GL of the mammalian OB including the short axon cell, initially described by Ramon y Cajal (Ramon y Cajal 1911), which is believed to facilitate inter-glomerular communication (Liu et al. 2013). There is currently a debate as to whether all DA neurons in the OB should be classified as short axon cells (Kosaka and Kosaka 2016).

The number of glomeruli in the antennal lobe has been estimated at ~165 with counts ranging from 160–175 (Fonta et al. 1993; Galizia and Menzel 2001; Galizia et al. 1999). They represent the projection targets of four of the antennal nerve tracts: the T1 dorsal tract population with 71 glomeruli, the T2 lateral, internal tract population including 6 glomeruli, the T3 tract ventral population with 81 glomeruli and the T4 tract posterior population with seven glomeruli (Fonta et al. 1993). The number of honey bee AmORs is approximately equal to the number of glomeruli in the honey bee antennal lobe (160–170), consistent with a general one-receptor/one-neuron/one-glomerulus relationship (Robertson and Wanner 2006). Each glomerulus is identified by regions of increased synaptic density (revealed by the presynaptic marker anti-synapsin in Fig. 3B) in contrast to the aglomerular neuropil (the area without synapses, surrounded by glomeruli Fig. 3B). The diameter of the adult honey bee glomerulus varies between 15–60 μm, although the overall volume varies across the lifespan (Brown et al. 2002), reflecting plasticity in the AL neurons driven in part by odor processing. The ORN endings divide each glomerulus into two functionally distinct areas: a cortex (where ORN axons terminate) and a core (without ORN axons, Fig. 3D). In Figure 3D, we directly labeled these ORN endings using the neural tracer neurobiotin injected into the antenna. As with the mammalian OB, each glomerulus receives ORNs expressing a single type of OR in the cortex area (Table 1).

The size of the OB and AL and the numbers of glomeruli in these species (~165 in honey bee, ~3600 in mouse, and up to 5500 in human) differ substantially. Surprisingly, the diameter of a glomerulus is more similar in all three species, varying between 20–100 μm (Table 1), 20–60 μm in honey bee, from 45–100 μm in mouse and an average 60 μm in human. The size and synaptic organization of glomeruli may reflect a similar optimization of early olfactory processing in all three species.

Projection neurons

The OB sends output to other brain areas via mitral cells and tufted cells, whose apical and lateral dendrites traverse the External Plexiform Layer (EPL). Here these cell types also make dendro-dendritic synapses with inhibitory granule cells and axo-dendritic synapses with centrifugal fibers from neuromodulatory neurons (Rall et al. 1966; Shepherd 2003). The EPL also contains the cell bodies of the tufted cells, while the somata of the mitral cells make up the deeper, narrower mitral cell layer (MCL). Because the MCL is easily identified anatomically, the mitral cells have been more thoroughly investigated. In humans, there are ~51000 mitral cells at age 25, with a loss of ~520 mitral cells per year thereafter (Bhatnagar et al. 1987). It is not clear from these studies if the counts were only of mitral cells or of mitral and tufted cells together. In humans it is not established (to our knowledge) that mitral and tufted cells are glutamatergic, but it is only assumed from other mammalian studies. Many details regarding the organization of mitral and tufted cells in the human brain are still unknown. The axons of both mitral and tufted cells leave the OB through the Internal Plexiform Layer (IPL), and continue to other brain areas via the olfactory tract. These two cell types are believed to form parallel pathways for odor processing (Fukunaga et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2016).

In the mouse OB the mitral and tufted cells each extend an apical dendrite into a single glomerulus and their lateral dendrites spread through the EPL (Fig. 2B). Both cell types send axons to piriform cortex via the Internal Plexiform Layer (IPL) and fasciculate in the olfactory tract. Tufted cells also target the anterior olfactory nucleus (AON), at least in rodents (Haberly and Price 1977). Links between olfactory and auditory processing in humans have long been known (Belkin et al. 1997; Piesse 1857), and in mice the olfactory tubercle is a site of convergence for mitral cells and for auditory information (Wesson and Wilson 2010).

In keeping with the analogy to the mammalian OB, honey bee projection neurons (PNs) are analogues of mitral and tufted cells (Fig. 3A, Table 1). Odor information processed by uniglomerular projection neurons (uPNs) is sent to higher odor processing centers (lateral horn and mushroom bodies) where it converges with information from other sensory modalities, such as visual input (in the mushroom body) and with signals from reward-processing modulatory neurons. Dye injection into a single glomerulus (n=3, Table 1) identified at least five uPNs per glomerulus (similar to Rybak 2012); each uPN has dendrites in both glomerular cortex and core, and connects AL to the lateral horn and calyx of mushroom bodies via two major tracts: l- and m-antenno-protocerebral tracts (APTs) (Fig. 3A, C, E). In addition to the cholinergic uPNs, the AL also contains GABAergic multiglomerular (m)PNs, which target the lateral horn, but not the mushroom body (Fig. 3A), and have dendrites only in the glomerular cortex but not the core (Kirschner et al. 2006; Sinakevitch et al. 2013). uPNs connect the antennal lobe to the mushroom body and lateral horn by two major tracts that represent ventral and dorsal glomerular areas of the AL, differing in the specificity of odor processing: generalized odor for l-APT and specialized for m-APT (Carcaud et al. 2015; Yamagata et al. 2009). With the mushroom body and lateral horn as invertebrate analogues of piriform cortex and AON, respectively, could these two tracts correspond to the mitral and tufted cell pathways in the mammalian OB?

Local Inhibitory cells

The deepest layer of the human OB consists of mostly GABAergic granule cells (Ohm et al. 1990), the largest population of interneurons in the OB (Smith et al. 1991). This Granule Cell Layer (GCL) receives centrifugal fibers from various other brain areas, including from pyramidal neurons of the anterior olfactory nucleus (AON), a major part of which is located within the OB in humans (Kundua et al. 2013). Along with periglomerular cells (which provide intraglomerular inhibition), granule cells (which provide interglomerular inhibition) act as the local interneurons of the olfactory module (Doty 2012; Halász and Shepherd 1983; Mori et al. 1999; Shipley and Ennis 1996). The granule cells extend one long apical dendrite into EPL, where it branches extensively, and synapses onto the lateral dendrites of mitral and tufted cells (Fig. 1, 2A, C).

In the AL the analogues of periglomerular and granule cells are local interneurons (LNs) (Dacks et al. 2010; Galizia et al. 1999; Kreissl et al. 2010; Meyer et al. 2013; Schafer and Bicker 1986; Sinakevitch et al. 2011). GABA immunoreactivity is distributed in both the core and cortex of each glomerulus (Fig. 3F). LNs come in two types: homo and hetero (het) LNs, which branch preferentially in the glomerular core and cortex, respectively (Fig. 3G; (Fonta et al. 1993; Galizia and Sachse 2010)). Each glomerulus has at least two glomerulus-specific het-LNs that have dendrites in both core and cortex and interconnect neighboring glomeruli via the core area (het-LN, Fig. 3F, G). In each glomerulus there is at least one GABAergic and one histaminergic het-LN (Dacks et al. 2010; Sinakevitch et al. 2013); both connect with at least 70 glomeruli but exclusively in the core area (Fonta et al. 1993; Girardin et al. 2013). Additionally, there are at least 20 homo-LNs (Fig. 3F, G), co-expressing GABA and allatostatin, an inhibitory neuropeptide, whose neurites branch in the glomerular core (Kreissl et al. 2010). This glomerular core, where inhibitory LNs target both PNs and other LNs, may thus be analogous to the mammalian EPL, as both are serving as a major site of interglomerular inhibition. The remaining aglomerular neuropil of the AL is characterized by neuronal axons from ORNs that organize in tracts T1–T4 (Fig. 3C), l- and m- uPNs, ml-APT mPNs (Fig. 3A), het and homo LNs (Fig. 3G), and neuromodulatory neurons. The aglomerular neuropil, with its abundance of axons, could be the analogue of the IPL in mammals.

Olfactory tract

The olfactory tract carries afferent axons of principal neurons from the OB to higher brain centers, including the AON and piriform cortex. It also carries centrifugal projections of central neurons into the OB. In the human OB the olfactory tract carries some very long, myelinated axons from mitral cells, but the precise anatomical structure and targeting is unclear (Sarnat and Yu 2016). The mouse olfactory tract has a clear dorso-ventral and lateral distribution of both axons that enter and those that leave the olfactory bulb (Kang et al. 2011; Ramon y Cajal 1911). Similarly, exiting fibers of the AL are organized into dorso-ventral tracts (from l- and m-APT neurons) and a ventro-lateral distribution (from the AL neurons located ventrally (Kirschner et al. 2006; Sinakevitch et al. 2013).

Neuromodulation

In the OB, the primary neuromodulatory circuits are centrifugal axons from cholinergic, noradrenergic and serotoninergic neurons whose somata lie in other brain areas (Doty 2012). These axons arrive via the olfactory tract and branch in the GCL, IPL, EPL, and GL. Dopamine (DA) is released by dopaminergic cells located in the OB itself. In the honey bee, all cell bodies of analogous monoaminergic cells are located outside the AL, primarily in the subesophageal ganglia (Fig. 3L); reviewed in (Bicker 1999), a center that receives gustatory sensory input and contains motoneurons innervating muscles involved in feeding behavior and head movements. The anatomical organization of these neuromodulators in the AL and OB in the honey bee, mouse, and human are summarized in Table 2 and schematized in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Primary antibodies and cellular markers used in this study

| Antibodies/marker | Host | Dilution | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPI (4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) | 1:50000 | Nuclear marker | ||

| Neurobiotin | 2% in water | Dye neuronal tracer | ||

| Anti-synapsin | Mouse monoconal | 1:1000 | DHB | Presynaptic marker in insects |

| Anti-serotonin | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:1000 | Millipore | Serotoninergic profile |

| Anti-glutamate | Rabbit-polyclonal | 1:1000 | GEMAC | Glutamatergic profile |

| Anti-GABA | Rabbit-polyclonal | 1:100 | GEMAC | GABAergic profile |

| Anti-noradrenaline | Rabbit-polyclonal | 1:500 | GEMAC | Noradrenergic profile |

| Anti-dopamine | Rabbit-polyclonal | 1:500 | GEMAC | Dopaminergic profile |

| Anti-octopamine | Rabbit-polyclonal | 1:500 | GEMAC | Octopaminergic profile |

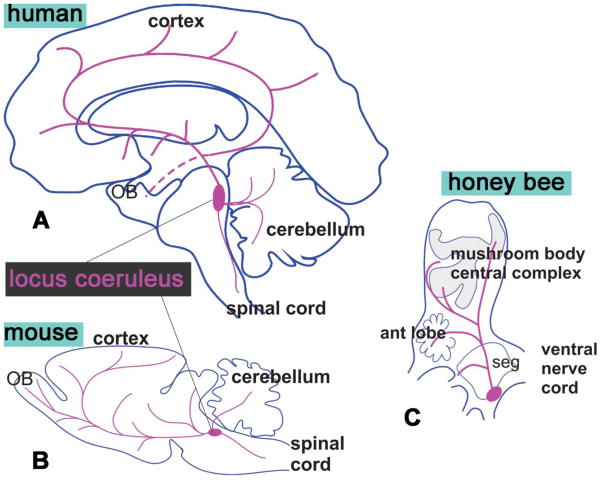

Figure 4. Schematic comparison of the distribution of noradrenaline in human and mouse and of octopamine/tyramine (an analogue of noradrenaline) in the honey bee.

In human (A), and mouse (B) the noradrenergic cell bodies are in locus coeruleus. C. A sagittal schematic of bee shows cell bodies of the octopaminergic/tyraminergic cells in the caudal area called subesophageal ganglion (SEG) that receives gustatory input and innervates the mouthpart of the bees.

Noradrenaline/Octopamine

In the mammalian OB, the main source of noradrenaline is the Locus Coeruleus (LC), review in (Feinstein et al. 2016; Szabadi 2013), which contains about 45000–60000 putatively noradrenergic (NA) neurons in a healthy young adult human (Baker et al. 1989). The number of cell bodies in adult mouse LC number ~1500 (Sturrock and Rao 1985), and a large proportion of these (40%) project to the rat main OB.

NA modulation in mice has been investigated extensively (Eckmeier and Shea 2014; Linster et al. 2011), since NA is required for many olfactory learning tasks in the mouse and “might have a finely tuned action on the OB depending on the type of olfactory behavior at stake” (Vinera et al. 2015). NA instantaneously regulates odor processing in the OB, and the response of neurons in the glomerular module naturally depends upon the expression of postsynaptic noradrenergic receptors (Szabadi 2013). The primary mechanism of action for NA is thought to be direct suppression of granule cell activity (Linster et al. 2011), resulting in disinhibition of mitral and tufted cells, increasing instantaneous gain and facilitating OB plasticity. In Figure 2D we noted NA-labeled cell bodies in the LC of neonatal mice. At this stage, NA labeled fibers are abundant in the GCL, IPL, EPL and each glomerulus is surrounded by its own set of fibers (Fig. 2E) At 6 months of age these fibers are still distributed in the same layers, but more sparsely (Fig. 2F). This is similar to the innervation pattern previously shown in rats (Shipley et al. 1985), where fibers originating from cells located in LC are distributed within GCL and IPL and sparsely innervate the MCL, EPL and GL. In contrast to neonatal mice, we observed that NA fibers are not homogenously distributed in adult mice; instead, in the adult these fibers have more extensive branching in the GCL as well as the GL, suggesting potential sharpening of functional neuromodulation by NA during development (Fig. 2 E, F).

Octopaminergic/tyraminergic fibers in the honey bee AL emanate from ventral unpaired median (VUM) neurons (Fig. 3A, H, L; (Hammer 1993; Hammer and Menzel 1998; Kreissl et al. 1994; Sinakevitch et al. 2005)), target multiple glomeruli, and have a similar distribution (and possible function) to the NA fibers in mammalian OB. In both cases the organization is similar: the cell bodies are in a caudal region of the brain (LC in mammals and SEG in insects) and innervated by gustatory sensory neurons, the cells then send their fibers throughout the brain (including olfactory areas, Fig. 4). Octopamine is not distributed throughout the glomeruli but only in the glomerular cortex, targeting AL neurons that branch there (Fig. 3H), much as NA is primarily found surrounding but not penetrating the glomerulus in mouse OB. Both NA and octopamine/tyramine play significant roles in odor learning and discrimination (Eckmeier and Shea 2014; Linster et al. 2011; Roeder 2005; Veyrac et al. 2008; Vinera et al. 2015).

Serotonin

Serotonin (5-HT) has been shown to play a role in olfactory associative conditioning and short-term memory (Fletcher and Chen 2010; Moriizumi et al. 1994). 5-HT innervation of the OB originates from cell bodies in the raphe nuclei, with the GCL and GL innervated by the dorsal and medial raphe nucleus, respectively (Steinfeld et al. 2015). Figure 2G illustrates 5-HT immunoreactivity in adult mouse OB glomeruli and, in contrast to the NA immunostaining (Fig. 2F), the GL is thoroughly innervated by 5HT-immunoreactive fibers. Overall, 5-HT reactivity is present in all layers of the OB (see also (McLean and Shipley 1987)). 5-HT also inhibits granule cells and is involved in OB plasticity (Dugue and Mainen 2009; Huang et al. 2017; Petzold et al. 2009).

In humans, serotoninergic fibers from neurons of the dorsal and medial raphe nucleus also innervate the OB, with anti-serotonin immunoreactivity present in each layer of the human OB but especially concentrated in the GL (Smith et al. 1993).

Serotoninergic fibers in the honey bee AL originate from the deutocerebral giant neuron (DCG) whose cell body lies just outside of the AL in the lateral cell cluster where the AL connects with the SEG (Fig. 3C, I, L; (Dacks et al. 2006; Rehder et al. 1987)) and these fibers are distributed throughout the entire glomerulus (Fig. 3I), just as in mammals. In both phyla the cell bodies lie outside of the primary olfactory structure and innervation is very tightly organized in the glomeruli and less dense in other areas.

Dopamine

Each glomerulus in the mouse, as well as in the human, has associated dopaminergic neurons. These were originally thought to be PG cells or possibly a subclass of tufted cells but because they target multiple glomeruli they are best classified as so-called short axon cells (Bonzano et al. 2016; Kiyokage et al. 2010). These DA cells belong to two classes, one that targets ~6 glomeruli each, and a rarer class that targets nearly 40 (Kiyokage et al. 2010).

In contrast, in the honey bee, the dopaminergic fibers are absent in glomeruli. Instead, they innervate the neuropil just outside of and surrounding the glomerulus, and are especially concentrated in the aglomerular neuropil (Fig. 3C, J–L; (Schafer and Rehder 1989)). Little is known about the computational properties of this aglomerular neuropil, characterized by the absence of synaptic machinery. However, because the DA innervation is outside of the glomeruli, it is possible that at least four DA neurons modulate (potentially indirectly) the output of many glomeruli at once. If so, this would match the behavior of the short-axon cell in the OB, which also targets multiple glomeruli. However, unlike the DA cells that modulate the AL, which are driven by gustatory and motor states, it is less clear what determines the output of the DA cells in the OB.

Glia

Every layer of the OB also contains glial cells, which are essential to the metabolism of these neurotransmitters (Garcia-Gonzalez et al. 2013; Shipley and Ennis 1996). The AL also contains glia, but these do not penetrate deeply into core structures of glomeruli (Hahnlein and Bicker 1996).

Conclusion

Here we compared the structural and functional neuroanatomical organization of the mouse OB and honey bee AL, two animal model systems frequently investigated to understand olfactory coding. In spite of abundant literature on the human OB, much is still unknown about the cellular composition and chemical neuroanatomy of the primary olfactory system in healthy human adults. However, because the monoamine-containing modulatory neurons (serotonin, noradrenaline/octopamine) have a similar distribution and function in both phyla, the study of neuromodulation in both mouse and honey bee may help secure a broad-based understanding of animal olfaction that will apply to humans as well.

Materials and Methods

Honey bees (Apis mellifera)

Adult New World Carniolan™ pollen foragers from colonies maintained at Arizona State University.

Mice (Mus musculas)

Animal experiments were performed in compliance with protocols approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and within the guidelines established by NIH for the use and care of laboratory animals. Mice were maintained on a 12 hour light/dark cycle in standard housing conditions with food and water provided ad libitum. All mice used in this study were of a mixed genetic background.

Immunocytochemistry

Table 1 describes the antibodies and markers used here to reveal the neurotransmitter/neuromodulator distribution in the honey bee AL and mouse OB. For anti-serotonin and anti-synapsin staining, the fixative was 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (PBS). For octopamine, noradrenaline, dopamine, GABA and glutamate, the fixative was mixture 1.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.5% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer in the presence of 1 % sodium metabisulfite (SMB) or only 3.75 % glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer with 1% SMB.

Adult mice were anesthetized with tribromoethanol (Avertin, 250mg/kg), while neonatal mice were cryoanesthetized. Transcardial perfusions were then performed using the fixative optimized for the corresponding antibodies. Brains were then dissected and postfixed for 16 hours at 4 C. Bee brains were dissected under the fixative and left overnight at 4° C (one ml for each brain). Six adult mice and 4 postnatal day 1 (P1) mice were used in our experiments.

To examine octopamine, noradrenaline, dopamine, GABA, and glutamate immunoreactivity, olfactory bulbs and honey bee brains were incubated for 15 minutes in 0.05 M Tris-HCl-SMB buffer pH 7.5 containing 0.5% NaBH4 immediately after fixation. For anti-serotonin, and anti-synapsin staining the tissue was washed in PBS and for all immunocytochemical steps PBS with 0.5% Triton X100 was used (TX). Tissue was embedded in 4% agarose, and 60–300μm sections were collected using a vibratome (Leica 1000). After washing in 0.05M Tris-HCl-SMB buffer with 0.5% TX, sections were pre-incubated with 5% normal donkey serum for one hour; then the primary antibodies diluted in 0.05 Tris-HCl-SMB-TX buffers were applied for 24 hours at room temperature, pH 7.5. After washing in 0.05M Tris-HCl-TX, F(ab′)2 fragments of donkey anti-rabbit (or mouse) antibodies conjugated to either Cy3 or Cy5 were diluted 1:250 in 0.05M Tris-HCl-TX and used as the secondary antibody for 12 hours. After a final wash in Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.5, the sections were mounted on slides. DAPI (4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used as a fluorescent marker of cell nuclei in mouse brains. The DAPI was added in the last wash before mounting on a slide. For neurobiotin staining of the honey bee projection neurons the protocol described in Sinakevitch et al., 2013 was followed.

To test the specificity of immunostaining, working dilutions of the antibodies were preincubated overnight with corresponding small molecules conjugated to BSA obtained from GEMAC. The staining was abolished after these procedures.

Confocal Microscopy

Data were collected on a Leica SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, Bensheim, Germany) using a Leica HCX PLAPO CS 40x oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture: 1.25) with appropriate laser and filter combinations. Stacks of optical sections at one μm spacing were processed using Leica software (1024 x 1024 pixel resolution) either as a single slice or flattened confocal stacks (maximum intensity projections). Size, resolution, contrast and brightness of final images were adjusted with Adobe Photoshop software. The schematic drawings were done in Canvas X2017 software (ACD systems).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ryan Brackney for discussion of the work. Research on the honey bee was performed under awards to BHS from NIH-NIGMS (GM113967), NSF (1556337) the Human Frontiers Science Foundation. Research on the mouse was performed under an award from the Arizona Alzheimer’s Consortium (ADHS14-052688, BHS) and NIH R01-NS097537 to JN. RCG is supported by NIMH (R01MH106674) and NIBIB (R01EB021711). We thank the NIMBioS Workshop Olfactory Modeling. (March 1–4th, 2016, Knoxville, TN) for group discussion of the mammalian OB organization.

References

- Abel R, Rybak J, Menzel R. Structure and response patterns of olfactory interneurons in the honeybee, Apis mellifera. J Comp Neurol. 2001;437:363–383. doi: 10.1002/cne.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh R, Hassanzadeh G, Soleimani M, Joghataei Mt, Siavashi V, Khorgami Z, Hadjighassem M. Gender and age related changes in number of dopaminergic neurons in adult human olfactory bulb. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2015;69:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2015.07.003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchemneu.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker H. Species differences in the distribution of substance P and tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1986;252:206–226. doi: 10.1002/cne.902520206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KG, Tork I, Hornung JP, Halasz P. The human locus coeruleus complex: an immunohistochemical and three dimensional reconstruction study. Exp Brain Res. 1989;77:257–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00274983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkin K, Martin R, Kemp SE, Gilbert AN. Auditory Pitch as a Perceptual Analogue to Odor Quality. Psychological Science. 1997;8:340–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00450.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berck ME, et al. The wiring diagram of a glomerular olfactory system. eLife. 2016;5:e14859. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowicz DA, Trombley PQ, Shepherd GM. Evidence for glutamate as the olfactory receptor cell neurotransmitter. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:2557–2561. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar KP, Kennedy RC, Baron G, Greenberg RA. Number of mitral cells and the bulb volume in the aging human olfactory bulb: a quantitative morphological study. Anat Rec. 1987;218:73–87. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092180112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicker G. Biogenic amines in the brain of the honeybee: Cellular distribution, development, and behavioral functions. Microscopy research and technique. 1999;44:166–178. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19990115/01)44:2/3<166::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonzano S, Bovetti S, Gendusa C, Peretto P, De Marchis S. Adult Born Olfactory Bulb Dopaminergic Interneurons: Molecular Determinants and Experience-Dependent. Plasticity Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2016;10:189. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill MF, Rosenbaum T, Reus I, Kleineidam CJ, Nawrot MP, Rossler W. Parallel processing via a dual olfactory pathway in the honeybee. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2443–2456. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4268-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Napper RM, Thompson CM, Mercer AR. Stereological analysis reveals striking differences in the structural plasticity of two readily identifiable glomeruli in the antennal lobes of the adult worker honeybee. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8514–8522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08514.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcaud J, Giurfa M, Sandoz JC. Parallel Olfactory Processing in the Honey Bee Brain: Odor Learning and Generalization under Selective Lesion of a Projection. Neuron Tract Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2015;9:75. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2015.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Marachlian E, Assisi C, Huerta R, Smith BH, Locatelli F, Bazhenov M. Learning modifies odor mixture processing to improve detection of relevant components. J Neurosci. 2015;35:179–197. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2345-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacks AM, Christensen TA, Hildebrand JG. Phylogeny of a serotonin-immunoreactive neuron in the primary olfactory center of the insect brain. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:727–746. doi: 10.1002/cne.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacks AM, Reisenman CE, Paulk AC, Nighorn AJ. Histamine-immunoreactive local neurons in the antennal lobes of the hymenoptera. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:2917–2933. doi: 10.1002/cne.22371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly KC, Christensen TA, Lei H, Smith BH, Hildebrand JG. Learning modulates the ensemble representations for odors in primary olfactory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004a;101:10476–10481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.04019021010401902101. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly KC, Wright GA, Smith BH. Molecular features of odorants systematically influence slow temporal responses across clusters of coordinated antennal lobe units in the moth Manduca sexta. J Neurophysiol. 2004b;92:236–254. doi: 10.1152/jn.01132.200301132.2003. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL. Olfaction in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Neurobiology of Disease. 2012;46:527–552. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.026. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugue GP, Mainen ZF. How serotonin gates olfactory information flow. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:673–675. doi: 10.1038/nn0609-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckmeier D, Shea SD. Noradrenergic Plasticity of Olfactory Sensory Neuron Inputs to the Main Olfactory Bulb. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:15234–15243. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0551-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein DL, Kalinin S, Braun D. Causes, consequences, and cures for neuroinflammation mediated via the locus coeruleus: noradrenergic signaling system. J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 2):154–178. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein P, Mombaerts P. A contextual model for axonal sorting into glomeruli in the mouse olfactory system. Cell. 2004;117:817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellous JM, Linster C. Computational models of neuromodulation. Neural Comput. 1998;10:771–805. doi: 10.1162/089976698300017476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez PC, Locatelli FF, Person-Rennell N, Deleo G, Smith BH. Associative conditioning tunes transient dynamics of early olfactory processing. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:10191–10202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1874-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher ML, Chen WR. Neural correlates of olfactory learning: Critical role of centrifugal neuromodulation. Learn Mem. 2010;17:561–570. doi: 10.1101/lm.941510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonta C, Sun XJ, Masson C. Morphology and Spatial-Distribution of Bee Antennal Lobe Interneurons Responsive to Odors. Chem Senses. 1993;18:101–119. doi: 10.1093/chemse/18.2.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga I, Berning M, Kollo M, Schmaltz A, Schaefer AT. Two distinct channels of olfactory bulb output. Neuron. 2012;75:320–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizia CG, Menzel R. The role of glomeruli in the neural representation of odours: results from optical recording studies. Journal of insect physiology. 2001;47:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(00)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizia CG, Rossler W. Parallel olfactory systems in insects: anatomy and function. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:399–420. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galizia CG, Sachse S. Odor Coding in Insects. In: Menini A, editor. The Neurobiology of Olfaction. Frontiers in Neuroscience. Boca Raton (FL): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Galizia CG, Sachse S, Rappert A, Menzel R. The glomerular code for odor representation is species specific in the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:473–478. doi: 10.1038/8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez D, Murcia-Belmonte V, Clemente D, De Castro F. Olfactory system and demyelination. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2013;296:1424–1434. doi: 10.1002/ar.22736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin CC, Kreissl S, Galizia CG. Inhibitory connections in the honeybee antennal lobe are spatially patchy. J Neurophysiol. 2013;109:332–343. doi: 10.1152/jn.01085.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glusman G, Yanai I, Rubin I, Lancet D. The complete human olfactory subgenome. Genome Res. 2001;11:685–702. doi: 10.1101/gr.171001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golgi C. Sulli fina struttura dei bulbi olfattorii. Riv Sper Freniatr. 1875;1:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Haberly LB, Price JL. The axonal projection patterns of the mitral and tufted cells of the olfactory bulb in the rat. Brain Research. 1977;129:152–157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahnlein I, Bicker G. Morphology of neuroglia in the antennal lobes and mushroom bodies of the brain of the honeybee. J Comp Neurol. 1996;367:235–245. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960401)367:2<235::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halász N, Shepherd GM. Neurochemistry of the vertebrate olfactory bulb. Neuroscience. 1983;10:579–619. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90206-3. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4522(83)90206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer M. An Identified Neuron Mediates the Unconditioned Stimulus in Associative Olfactory Learning in Honeybees. Nature. 1993;366:59–63. doi: 10.1038/366059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer M, Menzel R. Multiple sites of associative odor learning as revealed by local brain microinjections of octopamine in honeybees. Learn Memory. 1998;5:146–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand JG, Shepherd GM. Mechanisms of olfactory discrimination: converging evidence for common principles across phyla. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:595–631. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogland PV, Huisman E. Tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive structures in the aged human olfactory bulb and olfactory peduncle. J Chem Neuroanat. 1999;17:153–161. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(99)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Thiebaud N, Fadool DA. Differential serotonergic modulation across the main and accessory olfactory bulbs. The Journal of physiology. 2017 doi: 10.1113/jp273945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huart C, Rombaux P, Hummel T. Plasticity of the human olfactory system: the olfactory bulb. Molecules. 2013;18:11586–11600. doi: 10.3390/molecules180911586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T. The development of the olfactory and the accessory olfactory formations in human embryos and fetuses. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1940;73:431–468. doi: 10.1002/cne.900730305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T. Construction of functional neuronal circuitry in the olfactory bulb. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2014;35:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.07.012. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang N, Baum MJ, Cherry JA. Different Profiles of Main and Accessory Olfactory Bulb Mitral/Tufted Cell Projections Revealed in Mice Using an Anterograde Tracer and a Whole-Mount, Flattened Cortex Preparation. Chemical Senses. 2011;36:251–260. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupp UB. Olfactory signalling in vertebrates and insects: differences and commonalities. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:188–200. doi: 10.1038/nrn2789. doi: http://www.nature.com/nrn/journal/v11/n3/suppinfo/nrn2789_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharlamova AS, Barabanov VM, Saveliev SV. Development of human olfactory bulbs in prenatal ontogenesis: An immunochistochemical study with markers of presynaptic terminals (anti-SNAP-25, synapsin-I, and synaptophysin) Russian Journal of Developmental Biology. 2015;46:137–147. doi: 10.1134/s1062360415030054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner S, Kleineidam CJ, Zube C, Rybak J, Grunewald B, Rossler W. Dual olfactory pathway in the honeybee, Apis mellifera. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:933–952. doi: 10.1002/cne.21158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyokage E, et al. Molecular identity of periglomerular and short axon cells. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:1185–1196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3497-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka T, Kosaka K. Neuronal organization of the main olfactory bulb revisited. Anatomical Science International. 2016;91:115–127. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreissl S, Eichmuller S, Bicker G, Rapus J, Eckert M. Octopamine-like immunoreactivity in the brain and subesophageal ganglion of the honeybee. J Comp Neurol. 1994;348:583–595. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreissl S, Strasser C, Galizia CG. Allatostatin immunoreactivity in the honeybee brain. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:1391–1417. doi: 10.1002/cne.22343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krofczik S, Menzel R, Nawrot MP. Rapid odor processing in the honeybee antennal lobe network. Front Comput Neurosci. 2008;2:9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.10.009.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf J, Kelber C, Bieringer K, Rössler W. Olfactory subsystems in the honeybee: sensory supply and sex specificity. Cell and tissue research. 2014;357:583–595. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-1892-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundua K, Nandyb S, Tapadarc A, RKG, AS, SP Histological observations on the anterior olfactory nucleus in human. Journal of the Anatomical Society of India. 2013;62:62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson MC, Domingos AI, Jones WD, Chiappe ME, Amrein H, Vosshall LB. Or83b encodes a broadly expressed odorant receptor essential for Drosophila olfaction. Neuron. 2004;43:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.019S0896627304005264. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster C, Hasselmo M. Modulation of inhibition in a model of olfactory bulb reduces overlap in the neural representation of olfactory stimuli. Behavioural brain research. 1997;84:117–127. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)83331-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster C, Nai Q, Ennis M. Nonlinear effects of noradrenergic modulation of olfactory bulb function in adult rodents. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2011;105:1432–1443. doi: 10.1152/jn.00960.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linster C, Smith BH. A computational model of the response of honey bee antennal lobe circuitry to odor mixtures: overshadowing, blocking and unblocking can arise from lateral inhibition. Behavioural brain research. 1997;87:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)02271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Savya S, Urban NN. Early Odorant Exposure Increases the Number of Mitral and Tufted Cells Associated with a Single Glomerulus. J Neurosci. 2016;36:11646–11653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0654-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Plachez C, Shao Z, Puche A, Shipley MT. Olfactory bulb short axon cell release of GABA and dopamine produces a temporally biphasic inhibition-excitation response in external tufted cells. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2916–2926. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3607-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli FF, Fernandez PC, Villareal F, Muezzinoglu K, Huerta R, Galizia CG, Smith BH. Nonassociative plasticity alters competitive interactions among mixture components in early olfactory processing. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1111/ejn.12021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresh A, Gil DR, Whitman MC, Greer CA. Principles of Glomerular Organization in the Human Olfactory Bulb - Implications for Odor Processing. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean JH, Shipley MT. Serotonergic afferents to the rat olfactory bulb: I. Origins and laminar specificity of serotonergic inputs in the adult rat. J Neurosci. 1987;7:3016–3028. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-10-03016.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel R, Giurfa M. Cognition by a mini brain. Nature. 1999;400:718–719. doi: 10.1038/23371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith M. Human Vomeronasal Organ Function: A Critical Review of Best and Worst Cases. Chemical Senses. 2001;26:433–445. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Galizia CG, Nawrot MP. Local interneurons and projection neurons in the antennal lobe from a spiking point of view. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:2465–2474. doi: 10.1152/jn.00260.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missbach C, Dweck HKM, Vogel H, Vilcinskas A, Stensmyr MC, Hansson BS, Grosse-Wilde E. Evolution of insect olfactory receptors. eLife. 2014;3:e02115. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P, et al. Visualizing an olfactory sensory map. Cell. 1996;87:675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR. There Are No Killer Apps but Connecting Neural Activity to Behavior through Computation Is Still a Good Idea. In: Redish D, Gordon JA, Lupp J, editors. Computational Psychiatry: New Perspectives on Mental iIlness vol. 20 series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2016. pp. 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Nagao H, Yoshihara Y. The Olfactory Bulb: Coding and Processing of Odor Molecule Information. Science. 1999;286:711. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriizumi T, Tsukatani T, Sakashita H, Miwa T. Olfactory disturbance induced by deafferentation of serotonergic fibers in the olfactory bulb. Neuroscience. 1994;61:733–738. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucignat-Caretta C, Redaelli M, Caretta A. One nose, one brain: contribution of the main and accessory olfactory system to chemosensation. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy. 2012;6:46. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2012.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GJ, Darcy DP, Isaacson JS. Intraglomerular inhibition: signaling mechanisms of an olfactory microcircuit. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:354–364. doi: 10.1038/nn1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama S, Homma R, Imamura F. Neuronal organization of olfactory bulb circuits. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2014:8. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino H, Nishikawa M, Mizunami M, Yokohari F. Functional and topographic segregation of glomeruli revealed by local staining of antennal sensory neurons in the honeybee Apis mellifera. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:161–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.22064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm TG, Braak E, Probst A. Somatostatin-14-like immunoreactive neurons and fibres in the human olfactory bulb. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1988a;179:165–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00304698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm TG, Braak E, Probst A, Weindl A. Neuropeptide Y-like immunoreactive neurons in the human olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 1988b;451:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90774-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm TG, Muller H, Braak E. Calbindin-D-28k-like immunoreactive structures in the olfactory bulb and anterior olfactory nucleus of the human adult: distribution and cell typology--partial complementarity with parvalbumin. Neuroscience. 1991;42:823–840. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90047-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohm TG, Muller H, Ulfig N, Braak E. Glutamic-acid-decarboxylase-and parvalbumin-like-immunoreactive structures in the olfactory bulb of the human adult. J Comp Neurol. 1990;291:1–8. doi: 10.1002/cne.902910102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RM, Pinto JM. Olfaction: anatomy, physiology, and disease. Clin Anat. 2014;27:54–60. doi: 10.1002/ca.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold GC, Hagiwara A, Murthy VN. Serotonergic modulation of odor input to the mammalian olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nn.2335. doi: http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v12/n6/suppinfo/nn.2335_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piesse GWS. The Art of Perfumery. 1857. [Google Scholar]

- Rall W, Shepherd GM, Reese TS, Brightman MW. Dendrodendritic synaptic pathway for inhibition in the olfactory bulb. Experimental Neurology. 1966;14:44–56. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(66)90023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramon y Cajal S. Histology of the nervous system of man and vertebras. Paris: Maloine; 1911. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rehder V, Bicker G, Hammer M. Serotonin-immunoreactive neurons in the antennal lobes and suboesophageal ganglion of the honeybee. Cell and tissue research. 1987;247:59–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00216547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richard MB, Taylor SR, Greer CA. Age-induced disruption of selective olfactory bulb synaptic circuits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15613–15618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007931107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HM, Wanner KW. The chemoreceptor superfamily in the honey bee, Apis mellifera: expansion of the odorant, but not gustatory, receptor family. Genome Res. 2006;16:1395–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.5057506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Gil DJ, Bartel DL, Jaspers AW, Mobley AS, Imamura F, Greer CA. Odorant receptors regulate the final glomerular coalescence of olfactory sensory neuron axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:5821–5826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417955112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder T. Tyramine and octopamine: ruling behavior and metabolism. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:447–477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak J. The digital honey bee atlas. In: Galizia CG, Eisenhardt D, Giurfa M, editors. Honeybee Neurobiology and Behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sachse S, Galizia CG. The coding of odour-intensity in the honeybee antennal lobe: local computation optimizes odour representation. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2119–2132. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnat HB, Yu W. Maturation and Dysgenesis of the Human Olfactory Bulb. Brain Pathology. 2016;26:301–318. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Pellegrino M, Nakagawa T, Nakagawa T, Vosshall LB, Touhara K. Insect olfactory receptors are heteromeric ligand-gated ion channels. Nature. 2008;452:1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature06850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer S, Bicker G. Distribution of GABA-like immunoreactivity in the brain of the honeybee. J Comp Neurol. 1986;246:287–300. doi: 10.1002/cne.902460302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer S, Rehder V. Dopamine-like immunoreactivity in the brain and suboesophageal ganglion of the honeybee. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:43–58. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuker M, Yamagata N, Nawrot MP, Menzel R. Parallel representation of stimulus identity and intensity in a dual pathway model inspired by the olfactory system of the honeybee. Front Neuroeng. 2011;4:17. doi: 10.3389/fneng.2011.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa NE, Urban NN. Dendritic processing within olfactory bulb circuits. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:501–506. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd G. The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. 5. Oxford University Press; Oxford, New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley MT, Ennis M. Functional organization of olfactory system. Journal of neurobiology. 1996;30:123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199605)30:1<123::AID-NEU11>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley MT, Halloran FJ, de la Torre J. Surprisingly rich projection from locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb in the rat. Brain Res. 1985;329:294–299. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbering AF, Benton R. Ionotropic and metabotropic mechanisms in chemoreception: ‘chance or design’? EMBO reports. 2010;11:173–179. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinakevitch I, Mustard JA, Smith BH. Distribution of the octopamine receptor AmOA1 in the honey bee brain. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinakevitch I, Niwa M, Strausfeld NJ. Octopamine-like immunoreactivity in the honey bee and cockroach: comparable organization in the brain and subesophageal ganglion. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488:233–254. doi: 10.1002/cne.20572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinakevitch IT, Smith AN, Locatelli F, Huerta R, Bazhenov M, Smith BH. Apis mellifera octopamine receptor 1 (AmOA1) expression in antennal lobe networks of the honey bee (Apis mellifera) and fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) Front Syst Neurosci. 2013;7:70. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BH, Huerta R, Bazhenov M, Sinakevitch I. Distributed Plasticity for Olfactory Learning and Memory in the Honey Bee Brain The digital honey bee atlas. In: Galizia CG, Eisenhardt D, Giurfa M, editors. Honeybee Neurobiology and Behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. pp. 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Baker H, Greer CA. Immunohistochemical analyses of the human olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1993;333:519–530. doi: 10.1002/cne.903330405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RL, Baker H, Kolstad K, Spencer DD, Greer CA. Localization of tyrosine hydroxylase and olfactory marker protein immunoreactivities in the human and macaque olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 1991;548:140–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91115-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld R, Herb JT, Sprengel R, Schaefer AT, Fukunaga I. Divergent Innervation of the Olfactory Bulb by Distinct Raphe Nuclei. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2015;523:805–813. doi: 10.1002/cne.23713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock RR, Rao KA. A quantitative histological study of neuronal loss from the locus coeruleus of ageing mice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1985;11:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1985.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabadi E. Functional neuroanatomy of the central noradrenergic system. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:659–693. doi: 10.1177/0269881113490326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szyszka P, Gerkin RC, Galizia CG, Smith BH. High-speed odor transduction and pulse tracking by insect olfactory receptor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:16925–16930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412051111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veyrac A, Sacquet J, Nguyen V, Marien M, Jourdan F, Didier A. Novelty Determines the Effects of Olfactory Enrichment on Memory and Neurogenesis Through Noradrenergic Mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;34:786–795. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinera J, Kermen F, Sacquet J, Didier A, Mandairon N, Richard M. Olfactory perceptual learning requires action of noradrenaline in the olfactory bulb: comparison with olfactory associative learning. Learn Mem. 2015;22:192–196. doi: 10.1101/lm.036608.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosshall LB, Hansson BS. A Unified Nomenclature System for the Insect Olfactory Co-Receptor. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosshall LB, Wong AM, Axel R. An Olfactory Sensory Map in the Fly. Brain Cell. 2000;102:147–159. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00021-0. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner KW, Anderson AR, Trowell SC, Theilmann DA, Robertson HM, Newcomb RD. Female-biased expression of odourant receptor genes in the adult antennae of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Mol Biol. 2007a;16:107–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanner KW, Nichols AS, Walden KK, Brockmann A, Luetje CW, Robertson HM. A honey bee odorant receptor for the queen substance 9-oxo-2-decenoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007b;104:14383–14388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705459104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesson DW, Wilson DA. Smelling sounds: olfactory-auditory sensory convergence in the olfactory tubercle. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:3013–3021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6003-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman MC, Greer CA. Adult neurogenesis and the olfactory system. Progress in Neurobiology. 2009;89:162–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.003. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata N, Schmuker M, Szyszka P, Mizunami M, Menzel R. Differential odor processing in two olfactory pathways in the honeybee. Front Syst Neurosci. 2009;3:16. doi: 10.3389/neuro.06.016.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JM, Friedman C, Williams EM, Ross JA, Tonnes-Priddy L, Trask BJ. Different evolutionary processes shaped the mouse and human olfactory receptor gene families. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:535–546. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, De la Cruz O, Pinto JM, Nicolae D, Firestein S, Gilad Y. Characterizing the expression of the human olfactory receptor gene family using a novel DNA microarray. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Firestein S. The olfactory receptor gene superfamily of the mouse. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:124–133. doi: 10.1038/nn800. doi: http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v5/n2/suppinfo/nn800_S1.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]