Abstract

Background

Establishing a non-abstinence cocaine use outcome as clinically meaningful has been elusive, in part due to the lack of association between cocaine use outcomes and meaningful indicators of long-term functioning.

Methods

Using data pooled across 7 clinical trials evaluating treatments for cocaine (N = 718), a dichotomous indicator of functioning was created to represent a meaningful outcome (‘problem-free functioning’ - PFF), defined as the absence of problems across non-substance-related domains on the Addiction Severity Index. Its validity was evaluated at multiple time points (baseline, end-of-treatment, terminal follow-up) and used to explore associations with cocaine use.

Results

The percentage of participants meeting PFF criteria increased over time (baseline = 18%; end-of-treatment = 32%; terminal follow-up = 37%). At each time point, ANOVAs indicated those who met PFF criteria reported significantly less distress on the Brief Symptom Inventory and less perceived stress on the Perceived Stress Scale. Generalized linear models indicated categorical indices of self-reported cocaine use at the end of treatment were predictive of the probability of meeting PFF criteria during follow-up (β = −0.01, p < 0.01; 95% CI: −0.008 to −0.003), with those reporting 0 days or 1–4 days (‘occasional’ use) in the final month of treatment showing an increased likelihood of achieving PFF.

Conclusions

Initial validation of a proxy indicator of problem-free functioning demonstrated criterion validity and sensitivity to change over time. Frequency of cocaine use in the final month of treatment was associated with PFF during follow-up, with strongest associations between PFF and abstinence or ‘occasional’ use.

Keywords: Cocaine, Clinically meaningful outcome, Functioning, Addiction severity index

1. Introduction

The development and evaluation of treatments for cocaine use disorder has been hindered by the lack of a meaningful indicator of treatment success other than sustained abstinence (Donovan et al., 2012; Kiluk et al., 2016). Achievement of sustained abstinence is broadly accepted as clinically meaningful (McCann et al., 2015; Winchell et al., 2012) and the only valid endpoint accepted by the US Food and Drug Administration evaluating pharmacotherapies for drug use disorders (FDA: Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee, 2013). At the same time, it is increasingly regarded as an overly stringent and restrictive outcome, given the chronic relapsing nature of substance use disorders (Hser et al., 2008; McLellan et al., 2000; McLellan et al., 2014). Moreover, there is as yet no consensus regarding the ideal duration of abstinence needed to define a meaningful indicator of treatment success (Winchell et al., 2012).

Outcomes other than sustained abstinence, such as measures of cocaine reduction or short-term abstinence, may be more feasible and practical as endpoints in clinical trials of relatively short duration. For such an outcome to be considered ‘clinically meaningful’, it must demonstrate an association with long-term improvement in the multiple physical and psychosocial problems/consequences that characterize the disorder (Kiluk et al., 2016; Winchell et al., 2012). Yet measuring change in an individual’s functioning in these areas is challenging, due to issues such as the relatively short duration of most clinical trials and the extent to which the physical and psychosocial problems used as indicators of functioning are directly or indirectly related to drug use (McLellan et al., 1981). Moreover, there is little consensus regarding how best to measure functioning (Tiffany et al., 2012), which may include indicators such as quality of life indices (e.g., WHO Quality of Life), consequences of drug use (e.g., Inventory of Drug Use Consequences; Tonigan and Miller, 2002), or problem severity across a range of life domains (e.g., Addiction Severity Index - ASI; McLellan et al., 2006). While many clinical trials have demonstrated significant reductions in cocaine use (or greater rates of abstinence) over time, few have established an association between a specific level of reduction (or duration of abstinence) and meaningful indices of long-term functional improvement on these measures (Kiluk et al., 2016).

Our recent work provided some indications of an association between reduced cocaine use within treatment and fewer psychosocial problems during follow-up of up to one-year duration (Carroll et al., 2014a; Kiluk et al., 2014). Using data pooled from five randomized clinical trials (n = 434), we found that higher rates of cocaine abstinence during treatment (latent construct indicated by the percentage of days abstinent, maximum consecutive days abstinent, and percentage of cocaine positive urines) was associated with fewer days of psychosocial problems (self-reported ‘days of problems’ items across domains on the ASI) during follow-up (Kiluk et al., 2014). In separate analyses, we also found that several common cocaine use outcome measures were associated with a proxy measure of ‘good functioning’ at follow-up, which was a dichotomous variable defined as zero days of cocaine use and zero days of legal, employment, or psychiatric problems in the 28 days prior to interview as measured by the ASI (Carroll et al., 2014a). While our results showed some promise of this proxy measure as a potential indicator of treatment success, the validity of the measure was not examined; moreover, it did not clarify the relationship between cocaine use and the absence of problems in these areas, as the criteria for ‘good functioning’ included a requirement of sustained abstinence from cocaine.

Thus, in these analyses we built on our prior work by exploring the extent to which cocaine use (or specified duration of abstinence) is associated with an indicator of good functioning as defined by the absence of reported problems across the medical, employment, legal, family/social, and psychological domains on the ASI (i.e., removal of cocaine use criterion from prior measure), labelled here as ‘problem-free functioning’ (PFF). This study addressed three research questions: (1) to what extent was the PFF indicator consistent with other indicators of functioning (e.g., criterion validity)?; (2) to what degree did PFF status change across time (e.g., from baseline to end-of-treatment and follow-up)?; and (3) to what extent did measures of cocaine use at end-of-treatment predict PFF during follow-up?

2. Methods

2.1. Overview

Data for these analyses were drawn from a pooled dataset of 7 independent randomized controlled trials evaluating various behavioral and pharmacologic treatments for cocaine dependent individuals in different outpatient settings (Carroll et al., 2008, 2004, 2014b, 1998, 2016, 2012; Carroll et al., in press). The prior pooled dataset of 5 clinical trials reported in Carroll et al. (2014a), was expanded to include 2 recently completed trials. See Table 1 for an overview of the 7 trials. All trials shared a number of common characteristics: (1) similar inclusion/exclusion criteria; (2) interview-based assessments occurred at least weekly during treatment period, as well as at each follow-up visit after treatment termination (up to 12-months after treatment); and (3) at least weekly urine collection during 8- or 12-week treatment period and at each follow-up visit.

Table 1.

Overview of trials included in pooled dataset.

| Study | Behavioral Treatment Conditions | Medication Treatment Conditions | Length of Treatment (Weeks) | Length of Follow-up (Months) | N and sample | Citation for primary trial findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CBT vs TSF vs Clinical Management | Disulfiram vs no med | 12 | 12 | 122 cocaine and alcohol dependent outpatients | Carroll et al. (1998) |

| 2 | CBT vs IPT | Disulfiram vs placebo | 12 | 12 | 121 cocaine dependent outpatients | Carroll et al. (2004) |

| 3 | TSF + TAU vs TSF | Disulfiram vs placebo | 12 | 12 | 121 cocaine dependent methadone-maintained | Carroll et al. (2012) |

| 4 | CM + CBT vs CBT | Disulfiram vs placebo | 12 | 12 | 99 cocaine-dependent outpatients | Carroll et al. (2016) |

| 5 | CBT4CBT + TAU vs TAU | -- | 8 | 6 | 45 cocaine-dependent outpatients | Carroll et al. (2008) |

| 6 | CBT4CBT + TAU vs TAU | -- | 8 | 6 | 101 cocaine dependent methadone-maintained | Carroll et al. (2014b) |

| 7 | CBT4CBT + TAU vs TAU | Galantamine vs placebo | 12 | 6 | 120 cocaine dependent methadone-maintained | Carroll et al., in press |

Note: CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; TSF = Twelve-Step Facilitation; IPT = Interpersonal Therapy; TAU = Treatment As Usual; CM = Contingency Management; CBT4CBT = Computer Based Training for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

2.2. Participants

Participants in all trials: (1) were at least 18 years of age, (2) met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for current (past 30 days) cocaine abuse or dependence, (3) were psychiatrically stable for outpatient treatment, and (4) did not require alcohol or other drug detoxification. Table 1 displays sample sizes for each study. Study #5 (Carroll et al., 2008) included a general outpatient sample of substance users (N = 77), but only those who reported cocaine as their primary drug (n = 45) were included in the pooled dataset.

2.3. Assessments

See Table 2 for the schedule of assessments across trials. All trials assessed cocaine use with a Timeline Follow-back method (Robinson et al., 2014; Sobell and Sobell, 1992) for measuring self-reported cocaine use, as well as urine toxicology screens at each assessment. The common assessment battery included:

Table 2.

Common assessment battery schedule across trials.

| Assessment | Administration schedule

|

# of trials |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Weekly | Monthly | Post | FU | ||

| Demographic and Patient Characteristics | X | 7 | ||||

| Substance Use Calendar/TLFB | X | X | X | X | 7 | |

| Urine drug screen & breathalyzer | X | X | X | X | 7 | |

| Addiction Severity Index (ASI) | X | X | X | X | 7 | |

| Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) | X | X | X | X | 6 | |

| Risk Assessment Battery (RAB) | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | X | X | X | 4 | ||

2.3.1 Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992)

The Addiction Severity Index is an interview-based assessment for measuring the severity of problems across several domains (e.g., medical, legal, employment, family/social, psychological). For the current study, the participants’ report of the number of days in the past 28 that s/he experienced problems in that given domain was used as the indicator of problem severity. This was chosen based on our prior work (Kiluk et al., 2014) and the noted limitations of the composite scores (Makela, 2004; Melberg, 2004; Wertz et al., 1995).

2.3.2 Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983)

The Brief Symptom Inventory is a 53-item self-report instrument for measuring the level of distress regarding a number of symptoms using a 5-point Likert scale. It includes nine subscales: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism.

2.3.3 Risk Assessment Battery (RAB; Navaline et al., 1994)

The Risk Assessment Battery is a self-administered questionnaire used as a measure of HIV risk behaviors. It includes subscales for evaluating drug risk and sex risk, which are combined to yield a measure of total risk.

2.3.4 Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983)

The Perceived Stress Scale is a 10-item self-report instrument used for measuring the degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as stressful. Participants indicate how often in the past week they have experienced certain feelings or thoughts (e.g., “felt unable to control important things in your life”) using a 5 point Likert-type scale (from “never” = 0, to “very often” = 4). Scores are summed and averaged to produce a total score.

2.4. Data analysis

A dichotomous variable to indicate PFF was created using an aggregate of responses to the “days of problems” items across the 5 non-alcohol/drug domains on the ASI. If the sum of the responses to the items representing days of legal, medical, family/social, and psychological problems was equal to 0, then the PFF variable was coded “YES”; if the sum was greater than 0, then PFF was coded “NO”. A dichotomous outcome was chosen as it more readily lends itself to clinical interpretation than a continuous outcome (Falk et al., 2010). The number of participants meeting PFF criteria was calculated at several time points: baseline (week 0), end-of-treatment (week 8 or 12, depending on the duration of treatment in each trial), and terminal follow-up interview (6- or 12-months following end-of-treatment, see Table 1). Chi-square and ANOVAs compared demographic and baseline characteristic differences for individuals who met/did not meet PFF criteria at baseline. Criterion validity was evaluated with ANOVAs, comparing scores on measures of psychological functioning (e.g., BSI, PSS) and risk-taking (e.g., RAB) by PFF criteria status at each assessment point. In terms of association with cocaine use, we evaluated the extent to which continuous and discrete cocaine use measures (Carroll et al., 2014a) differed by PFF status at concurrent time points using ANOVAs and Chi-square. Generalized linear models evaluated potential end-of-treatment cocaine use categories as predictors of PFF during follow-up. Models analyzed the time-varying outcome of PFF status at each follow-up (1-, 3-, 6-, 12-months following end-of-treatment) with cocaine use categories as a predictor. Two separate models were evaluated due to the differing follow-up periods across studies (Study #s 1–4 included all 4 follow-up assessment points; Study #s 5–7 included only the first 3 follow-up assessment points).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

A total of 718 participants had data available for determination of PFF status at baseline, 580 (81%) at end-of-treatment, and 564 (79%) at terminal follow-up. The pooled sample was predominantly male (n = 457; 64%), single (n = 533; 74%), unemployed (n = 446; 62%), and had at least a high school education (n = 548; 76%) with an average age of 37 years (SD = 8.7). The distribution of self-reported race/ethnicity included a slight majority White/Caucasian (n = 369; 51%), with 36% Black/African-American (n = 258), 11% Hispanic (n = 79), and 2% reported “other.” Participants reported using cocaine 14.1 (SD = 8.7) days out of the 28-day period prior to baseline, with an average of 9.4 years (SD = 7.6) of cocaine use in their lifetime. The primary route of cocaine administration was smoking (73%).

3.2. Problem-free functioning: frequency and validity

At baseline, 129 participants (18%) met PFF criteria. Chi-square tests indicated a differential distribution according to racial/ethnic category [χ2 (3, 715) = 8.29, p < 0.05], with fewer Caucasians meeting PFF compared to non-PFF (43% vs. 53%), and more Hispanics meeting PFF than non-PFF (17% vs. 10%). Results of ANOVAs and Chi-squares indicated several characteristics differed according to PFF status in expected directions: a greater percentage of participants meeting PFF criteria were employed compared to those not meeting PFF criteria (46% vs. 36%, respectively; χ2 = 4.12, p < 0.05); fewer participants meeting PFF reported receiving public financial assistance compared to non-PFF (36% vs. 48%, respectively; χ2 = 6.2, p < 0.01). There were no differences in terms of cocaine severity; self-reported days of cocaine use in the 28-day period prior to baseline did not differ according to whether participants met PFF criteria (M = 15.3, SD = 8.7) or not (M = 13.9, SD = 8.6), nor did lifetime years of cocaine use (M = 9.7 vs. M = 9.4, respectively).

In terms of PFF status over time, 185 (32%) participants met PFF criteria at end-of-treatment, and 211 (37%) met PFF criteria at terminal follow-up. Of those who met PFF criteria at end-of-treatment, only 29% (n = 54) had met PFF criteria at baseline; whereas the majority (60%) continued to meet PFF at terminal follow-up. The distribution of days of problems across ASI domains at each time point indicated the psychological and employment domains were most likely to have ≥1 days of problems reported: 41% and 37% of participants reported at least 1 day of psychological or employment problems at end-of-treatment, respectively. Participants reporting ≥1 day of problems on other ASI domains were comparatively small: medical = 14%, family = 15%, social = 9%, legal = 6%.

Regarding criterion validity, results of ANOVAs evaluating differences on the BSI, PSS, and RAB by PFF status at each time point are displayed in Table 3. There were significant differences (p < 0.01) by PFF status on the BSI and PSS at each time point, with those meeting PFF criteria consistently demonstrating lower scores (indicating less symptom distress or perceived stress) compared to those not meeting PFF criteria. Those meeting PFF at baseline also demonstrated lower drug and sex risk scores on the RAB than those not meeting PFF. There were no differences on the drug risk score at end-of-treatment, nor were there any risk score differences on the RAB at terminal follow-up.

Table 3.

Scale score differences on BSI, PSS, and RAB according to Problem-Free Functioning status.

| Instrument (Baseline) |

Problem-Free Functioning | F | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||

| M | SD | n | M | SD | n | ||

| BSI | |||||||

| Anxiety | 0.76 | 0.77 | 485 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 104 | 25.55** |

| Depression | 1.00 | 0.83 | 485 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 104 | 3.14** |

| Hostility | 0.70 | 0.71 | 485 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 104 | 13.27** |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.84 | 0.85 | 485 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 104 | 27.91** |

| OCD | 1.00 | 0.85 | 485 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 104 | 18.93** |

| Paranoia | 0.92 | 0.78 | 485 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 104 | 26.68** |

| Phobic | 0.44 | 0.67 | 485 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 104 | 9.57** |

| Psychoticism | 0.77 | 0.77 | 485 | 0.40 | 0.58 | 104 | 20.93** |

| Somatization | 0.63 | 0.63 | 485 | 0.38 | 0.47 | 104 | 15.25** |

| PSS | |||||||

| Total Score | 18.90 | 6.00 | 304 | 17.20 | 5.60 | 58 | 3.93* |

| RAB | |||||||

| Drug Risk | 0.90 | 2.80 | 315 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 59 | 4.08* |

| Sex Risk | 4.00 | 3.10 | 316 | 2.90 | 2.40 | 59 | 7.15* |

| Total Scaled Score | 0.08 | 0.07 | 315 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 59 | 10.6** |

| (End-of-Treatment) | |||||||

| BSI | |||||||

| Anxiety | 0.45 | 0.66 | 290 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 136 | 27.05** |

| Depression | 0.67 | 0.84 | 290 | 0.27 | 0.54 | 136 | 26.64** |

| Hostility | 0.44 | 0.68 | 290 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 136 | 27.65** |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.50 | 0.74 | 290 | 0.28 | 0.63 | 136 | 8.92** |

| OCD | 0.71 | 0.80 | 285 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 133 | 37.50** |

| Paranoia | 0.58 | 0.68 | 290 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 136 | 14.34** |

| Phobic | 0.34 | 0.58 | 290 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 136 | 20.05** |

| Psychoticism | 0.50 | 0.68 | 290 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 136 | 15.68** |

| Somatization | 0.40 | 0.55 | 290 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 136 | 16.64** |

| PSS | |||||||

| Total Score | 18.40 | 6.90 | 181 | 15.00 | 6.50 | 84 | 14.70** |

| RAB | |||||||

| Drug Risk | 0.33 | 1.48 | 236 | 0.20 | 1.1 | 108 | 0.59 |

| Sex Risk | 3.41 | 2.57 | 236 | 2.69 | 2.23 | 108 | 6.34* |

| Total Scaled Score | 0.06 | 0.05 | 236 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 108 | 6.51* |

| (Terminal Follow-up) | |||||||

| BSI | |||||||

| Anxiety | 0.57 | 0.74 | 223 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 135 | 10.32** |

| Depression | 0.76 | 0.85 | 223 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 135 | 14.03** |

| Hostility | 0.58 | 0.77 | 223 | 0.28 | 0.52 | 135 | 16.20** |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.70 | 0.87 | 223 | 0.38 | 0.67 | 135 | 13.85** |

| OCD | 0.92 | 0.96 | 163 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 93 | 11.71** |

| Paranoia | 0.73 | 0.80 | 223 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 135 | 14.41** |

| Phobic | 0.41 | 0.67 | 223 | 0.19 | 0.37 | 135 | 12.80** |

| Psychoticism | 0.56 | 0.71 | 223 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 135 | 10.01** |

| Somatization | 0.53 | 0.67 | 223 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 135 | 9.28** |

| PSS | |||||||

| Total Score | 18.70 | 6.80 | 181 | 15.00 | 6.90 | 100 | 18.65** |

| RAB | |||||||

| Drug Risk | 0.50 | 2.1 | 165 | 0.17 | 1.05 | 101 | 2.15 |

| Sex Risk | 2.61 | 2.78 | 165 | 2.36 | 2.13 | 101 | 0.66 |

| Total Scaled Score | 0.05 | 0.06 | 165 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 101 | 2.07 |

p < .05

p < .01

3.3. Problem-free functioning: association with cocaine use outcomes

Results of ANOVAs and Chi-square examining cocaine use outcome measures by PFF status at end-of-treatment are displayed in Table 4. Participants meeting PFF criteria at end-of-treatment reported a greater percentage of days abstinent [F(1549) = 4.27, p < 0.05], fewer days of cocaine use in the final month of treatment [F(1572) = 6.47, p < 0.05] and were more likely to achieve at least 3 consecutive weeks of abstinence (χ2 = 9.31, p < 0.01) than those not meeting PFF criteria. The percentage of cocaine negative urine samples during treatment (based on number of total samples submitted) did not differ according to PFF criteria. However, among those who submitted at least three urine samples during treatment, those meeting PFF criteria were more likely to have 75% of all samples negative for cocaine compared to those not meeting PFF criteria (χ2 = 6.30, p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Cocaine Use Outcome Measures According to Problem-Free Functioning at End of Treatment.

| Problem-Free | Functioning Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | YES | |||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Continuous Measure | M (SD) | n | M (SD) | n | F | p |

| Days of cocaine use in final month of treatment | 8.3 (8.0) | 391 | 6.5 (7.4) | 183 | 6.47 | 0.01 |

| Percentage of days abstinent during treatment | 68.5 (27.4) | 377 | 73.6 (25.9) | 174 | 4.27 | 0.04 |

| Maximum consecutive days of abstinence during treatment | 18.7 (21.6) | 381 | 22.3 (25.4) | 180 | 3.14 | 0.08 |

| Percentage of cocaine negative urine samples during treatment | 56.2 (38.5) | 354 | 55.8 (38.6) | 167 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Dichotomous Measure | n | % | n | % | χ2 | p |

| Achieved at least 3 weeks of consecutive abstinence | 125 | 31.8 | 83 | 44.9 | 9.31 | < 0.01 |

| 75% of urines submitted were cocaine negative (≥ 3 urines submitted during treatment) | 53 | 13.4 | 40 | 21.6 | 6.30 | 0.01 |

A similar pattern of results was evident during the follow-up period. Those meeting criteria for PFF at terminal follow-up reported fewer days of cocaine use in the final follow-up month compared to those not meeting PFF criteria (M = 3.9, SD = 6.9 vs. M = 5.2, SD = 7.7, respectively; F(1559) = 3.94, p < 0.05). Also, those meeting PFF criteria reported a greater percentage of days abstinent during the entire follow-up period than those not meeting PFF criteria (M = 83.4, SD = 20.1 vs. M = 77.7, SD = 25.5, respectively; F(1562) = 7.72, p < 0.05). There were no differences in the percentage of participants who submitted a cocaine positive urine sample at the terminal follow-up interview according to PFF status.

3.4. Cocaine use categories and long-term problem-free functioning status

To explore potential cocaine frequency categories for distinguishing the likelihood of meeting PFF criteria, we examined the distribution of reported cocaine use days during the final month of treatment for those who met PFF at end-of-treatment. Results indicated 29% (n = 53) of the 183 participants who met PFF criteria at end-of-treatment reported 0 days of cocaine use in the final treatment month. Notably, 25% (n = 45) of those who met PFF criteria reported 1–4 days of cocaine use in the final month. Thus the majority (54%) of those who met PFF criteria at end-of-treatment reported fewer than 5 days of cocaine use in the final treatment month. Of those who met PFF at end-of-treatment and reported at least 5 days of cocaine use, 33% (n = 61) reported 5–14 days of cocaine use, and 13% (n = 24) reported 15–28 days of cocaine use. We included these non-abstinent categories (in addition to abstinence; 0 days) in generalized linear models to reflect ‘mild’ (i.e., ‘occasional’; 1–4 days), ‘moderate’ (5–14 days), and ‘heavy’ (15–28 days) frequency of cocaine use.

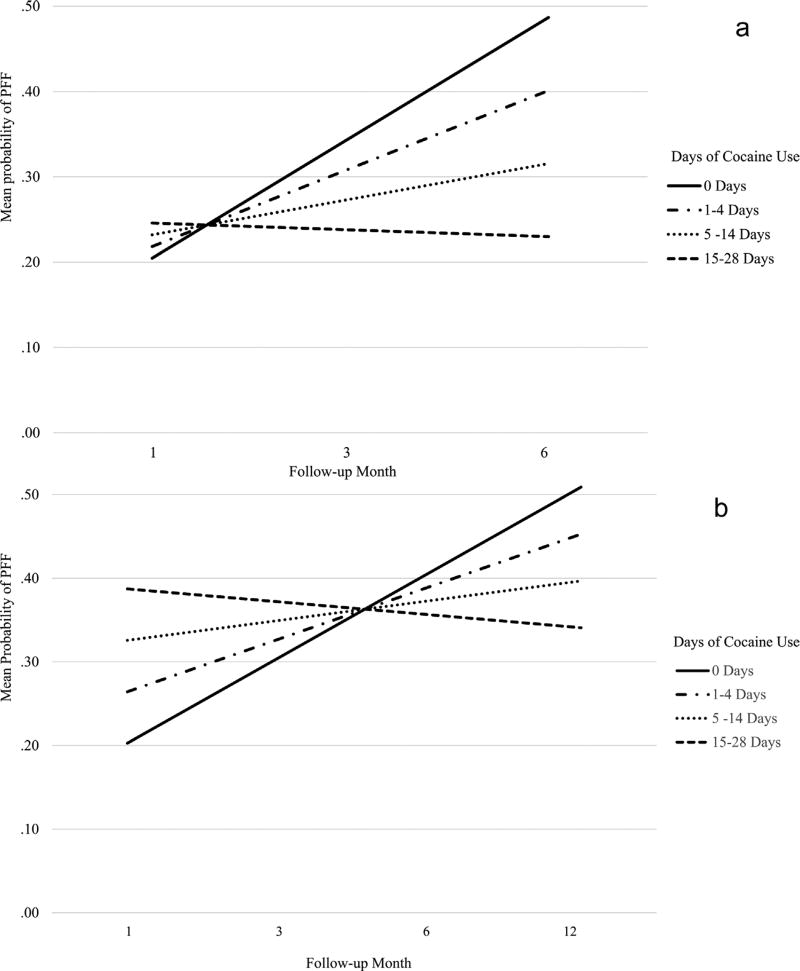

Results of generalized linear models examining the relationship between end-of-treatment cocaine use frequency categories and PFF during follow-up were as follows: in the model examining the studies with a 6-month follow-up period (Study #s 5–7; N = 252; Observations = 725), results indicated a significant interaction of cocaine use category x PFF status during follow-up (β = −0.05, p < 0.01; 95% CI: −0.071 to −0.028). In the model examining the studies with a 12-month follow-up period (Study #s 1–4; N = 356; Observations = 1291), results also indicated a significant interaction of cocaine use category x PFF criteria status during follow-up (β = −0.01, p < 0.01; 95% CI: −0.008 to −0.003). The significant interaction terms in both models indicated the lower cocaine use frequency categories had a greater increase in the probability of meeting PFF criteria during follow-up. These results are displayed graphically in Fig. 1a and b. Those reporting cocaine abstinence in the final month of treatment appeared to have the greatest increase in the likelihood of meeting PFF criteria at each follow-up interview; a comparatively smaller increase was found for those reporting ‘mild’ cocaine use (1–4 days). However, those reporting ‘moderate’ cocaine use (5–14 days) appeared to have only a slight increase, and those reporting ‘heavy’ use (15–28 days) had a reduction in the likelihood of meeting PFF criteria during follow-up.

Fig. 1.

(a) Probability of Meeting Good Functioning at Follow-up Based on Treatment Termination Cocaine Use Frequency Categories (Study #s 5–7). Caption: Generalized linear models examining probability of meeting good functioning criteria at each follow-up time point (1-, 3-, 6-months) according to cocaine use frequency categories at end-of-treatment. N = 252, Observations = 725. (b) Pbrobability of Meeting Good Functioning at Follow-up Based on Treatment Termination Cocaine Use Frequency Categories (Study #s 1–4). Caption: Generalized linear models examining probability of meeting good functioning criteria at each follow-up time point (1-, 3-, 6-, 12-months) according to cocaine use frequency categories at end-of-treatment. N = 356, Observations = 1291.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the validity of a novel proxy indicator of ‘problem-free functioning’ across a range of functional domains, and explored its relationship with cocaine use in one of the largest pooled datasets of cocaine clinical trials. The main findings were as follows: (1) those meeting PFF criteria at each time point had significantly lower scores on measures of psychiatric symptom distress and perceived stress than those not meeting PFF criteria; (2) the proportion of individuals meeting PFF criteria increased from baseline to the end-of-treatment, and further increased at the terminal follow-up interview; (3) those meeting PFF criteria at end-of-treatment reported significantly less cocaine use during treatment than those not meeting PFF; and (4) less cocaine use in the final month of treatment increased the probability of meeting PFF criteria at subsequent follow-up interviews. Taken together, the data are more consistent with a continuous relationship between PFF and cocaine use, with the likelihood of meeting PFF decreasing as cocaine use increases. Although a clear non-abstinence based cocaine use outcome that might predict the likelihood of good long-term functioning was not established here, this study may lay the groundwork for future exploration of potential cocaine use categories as meaningful outcomes.

This study utilized an alternative approach to evaluating levels of cocaine use that might be associated with improved long-term functioning by first defining an unequivocally positive functional outcome (i.e., the absence of recent problems across a range of life domains), and then exploring its relationship with cocaine use. While there are inherent limitations in dichotomizing a frequency variable, PFF demonstrated some promise as a tool for validating a meaningful cocaine use outcome measure. First, comparison of scores on validated assessments offered some indication of concurrent validity, such that those who met PFF criteria had less symptom distress, less perceived stress, and engaged in fewer risky behaviors. Second, participants who met PFF criteria at end-of-treatment reported less cocaine use during the entire treatment period, as well as in the final month of treatment, and were more likely to have at least 75% of urine samples submitted negative for cocaine. This suggests less frequent cocaine use, including continuous periods of self-reported and objectively verified cocaine abstinence, is more likely to be associated with a positive functional outcome than more frequent cocaine use, consistent with prior findings (Ghitza et al., 2007; Kiluk et al., 2014).

In terms of identifying a meaningful cocaine use outcome, individuals who reported cocaine abstinence in the final month of treatment were most likely to meet PFF criteria at end-of-treatment, and had greater probability of meeting PFF criteria up to 12-months after treatment. This is consistent with the prevailing acceptance of sustained abstinence as a valid endpoint for clinical trials evaluating pharmacotherapies for drug use disorders (Food and Drug Administration: Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee, 2013). It also advances our prior work (Kiluk et al., 2014) by indicating the timing of abstinence within treatment (i.e., final month of treatment) that was associated with a defined, positive long-term functional outcome. If replicated in other studies, a 28-day period of abstinence could represent a viable alternative to current requirements of long-term abstinence as the only viable indicator of treatment success and in turn move the field away from the relatively insensitive requirement of sustained abstinence (McLellan et al., 2000). Similarly, these data also indicated some support for a potentially meaningful distinction between occasional (i.e., ‘mild’) and more frequent cocaine use, as individuals reporting 1–4 days of cocaine use in the final month of treatment had a greater probability of meeting PFF criteria at end-of-treatment and at each follow-up interview than those reporting greater than 4 days of use. The increase in probability of meeting PFF for those reporting ‘mild’ cocaine use appeared similar to that found for those reporting abstinence, and was clearly different than those reporting more frequent use (‘moderate’ or ‘heavy’ use). This offers some promise in the search for a meaningful non-abstinence cocaine use endpoint analogous to efforts toward supporting ‘no heavy drinking days’ as a meaningful outcome (Falk et al., 2010). Again, this preliminary finding requires replication in multiple samples prior to being accepted as a meaningful endpoint.

The strengths of this study include the size and diversity of the sample, and the methodological rigor of the randomized clinical trials from which the data originate, particularly the comparatively high rates of follow-up. This pooled sample of 718 treatment seeking, cocaine-dependent individuals represents one of the largest and fairly complete data sets with this population. That being said, there are a number of limitations to be considered when interpreting these findings. In addition to the multiple statistical issues associated with dichotomization (e.g., loss of information on individual differences, loss of power; MacCallum et al., 2002), the PFF variable is based on self-report rather than objectively verified clinical data. While the ASI has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid (Alterman et al., 2000; Bovasso et al., 2001; Calsyn et al., 2004; McDermott et al., 1996; McLellan et al., 2006), some individuals may have falsely denied the existence of problems in the areas assessed. Relatedly, most of the significant relationships between PFF and cocaine use indicators were found for self-reported cocaine use rather than urine results. However, interpretation of measures based solely on urine toxicology is complicated by the various assumptions related to missing data (National Research Council, 2010). For instance, continuous measures such as the percentage of negative urine samples can be calculated multiple ways depending on how missing urine samples are handled, which can yield wildly different estimates of levels of drug use (Carroll et al., 2014a). Also, the dichotomous measure based on the submission of at least 75% of urines negative for cocaine was associated with PFF status, and rates of discrepancy between self-report and urine toxicology results were fairly low in these data (7–16% across trials), offering support for the accuracy of self-reported cocaine use. This study did not evaluate the effect of treatment on PFF status because the seven clinical trials included multiple combinations of behavioral and pharmacotherapies, often with active control conditions, making comparison between active and control conditions quite complicated in this pooled dataset. Lastly, the definition of PFF as zero days of problems may be overly strict and thus may fail to capture meaningful improvement in functioning. Our prior work considered the ‘days of problems’ items as a continuous variable, and found less cocaine use within treatment was associated with fewer problems during follow-up (Kiluk et al., 2014); the current study offered a novel approach that could be more easily interpreted clinically.

In sum, cocaine abstinence in the final month of treatment may potentially be a meaningful endpoint for clinical trials as it is related to concurrent positive functioning, and also predictive of long-term positive functioning. Furthermore, occasional cocaine use (i.e., 1–4 days per month; ‘mild’) appears worthy of further evaluation as a meaningful non-abstinence outcome. Exploration of the relationship between end-of-treatment abstinence (or occasional use) and long-term ‘problem-free functioning’ in other data is warranted, and may have significant benefit for future clinical trials of pharmacotherapies for cocaine or other drug use disorders. Although this proxy indicator of functioning may be a useful tool for evaluating cocaine use outcomes, other indicators of long-term positive functioning should be developed and explored. These indicators might include objectively verified data regarding employment and mental health status, as these were the domains in which participants most commonly reported problems. Defining and validating indices of treatment success (i.e., good outcome) should be a first step toward evaluating clinically meaningful reductions in cocaine use.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grants: R21DA041661 (Kiluk/Carroll, mPI), R01DA030369-04S1 (Carroll/Paris, mPI), and P50DA009241 (Carroll, PI). Support was also provided in part by Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations, Innovations, Opportunities, and Networks (ACTTION), a public-private partnership with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). NIDA and ACTTION had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Author Kiluk designed the study, planned the analyses and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Authors Babuscio and Nich contributed to the statistical analyses, interpretation of data, and the written manuscript. Author Carroll designed the 7 trials that contributed data to this study, contributed to the interpretation of analyses, and the written manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Author Carroll is a member of CBT4CBT, LLC, which makes CBT4CBT available to qualified clinical providers and organizations on a commercial basis. Dr. Carroll works with Yale University to manage any potential conflicts of interest. Authors Kiluk, Babuscio, and Nich declare no conflicts of interest.

A version of this report was presented at a meeting at the US FDA offices in October 2016, which was sponsored by ACTTION. We gratefully acknowledge the meeting participants for their feedback.

References

- Alterman AI, McDermott PA, Cook TG, Cacciola JS, McKay JR, McLellan AT, Rutherford MJ. Generalizability of the clinical dimensions of the Addiction Severity Index to nonopioid-dependent patients. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2000;14:287–294. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth. APA Press; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso GB, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Cook TG. Predictive validity of the Addiction Severity Index’s composite scores in the assessment of 2-year outcomes in a methadone maintenance population. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2001;15:171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsyn DA, Saxon AJ, Bush KR, Howell DN, Baer JS, Sloan KL, Malte CA, Kivlahan DR. The Addiction Severity Index medical and psychiatric composite scores measure similar domains as the SF-36 in substance-dependent veterans: concurrent and discriminant validity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance-Katz E, Rounsaville BJ. Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction. 1998;93:713–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Fenton LR, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Shi J, Rounsaville BJ. Efficacy of disulfiram and cognitive-behavioral therapy in cocaine-dependent outpatients: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;64:264–272. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Martino S, Nich C, Babuscio T, Gordon MA, Portnoy GA, Rounsaville BJ. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction. a randomized clinical trial of ‘CBT4CBT’. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:881–888. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Shi JM, Eagan D, Ball SA. Efficacy of disulfiram and Twelve Step Facilitation in cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, DeVito EE, Decker S, LaPaglia D, Duffey D, Babuscio TA, Ball SA. Towards empirical identification of a clinically meaningful indicator of treatment outcome for drug addiction: features of candidate indicators and evaluation of sensitivity to treatment effects and relationship to one year cocaine use follow-up outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014a;137:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, Gordon MA, Portnoy G, Marino D, Ball SA. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy: efficacy and durability of CBT4CBT among cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2014b;171:436–444. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Petry NM, Eagan DA, Shi JM, Ball SA. A randomized factorial trial of disulfiram and contingency management to enhance cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Devito EE, Shi J, Nich C, Sofuoglu M. A randomized trial of galantamine and computerized cognitive behavioral therapy for methadone maintained individuals with cocaine use disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11669. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Lichtenstein T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Bigelow GE, Brigham GS, Carroll KM, Cohen AJ, Gardin JG, Hamilton JA, Huestis MA, Hughes JR, Lindblad R, Marlatt GA, Preston KL, Selzer JA, Somoza EC, Wakim PG, Wells EA. Primary outcome indices in illicit drug dependence treatment research: systematic approach to selection and measurement of drug use endpoints in clinical trials. Addiction. 2012;107:694–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson M, Ryan M, Johnson B, Stout R, Litten RZ. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcoholclinical trials. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:2022–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food, Drug Administration: Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee. Probuphine (buprenorphine Hydrochloride Subdermal Implant) for Maintenance Treatment of Opioid Dependence. Silver Spring; MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Epstein DH, Preston KL. Psychosocial functioning and cocaine use during treatment: strength of relationship depends on type of urine-testing method. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Evans E, Huang D, Brecht ML, Li L. Comparing the dynamic course of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine use over 10 years. Addict. Behav. 2008;33:1581–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, Witkiewitz K, Babuscio TA, Carroll KM. What happens in treatment doesn’t stay in treatment: cocaine abstinence during treatment is associated with fewer problems at follow-up. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014;82:619–627. doi: 10.1037/a0036245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Carroll KM, Duhig A, Falk DE, Kampman K, Lai S, Litten RZ, McCann DJ, Montoya ID, Preston KL, Skolnick P, Weisner C, Woody G, Chandler R, Detke MJ, Dunn K, Dworkin RH, Fertig J, Gewandter J, Moeller FG, Ramey T, Ryan M, Silverman K, Strain EC. Measures of outcome for stimulant trials: ACTTION recommendations and research agenda. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol. Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makela K. Studies of the reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity Index. Addiction. 2004;99:398–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00665.x. discussion 411–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann DJ, Ramey T, Skolnick P. Outcome measures in medication trials for substance use disorders. Curr. Treat. Opt. Psychiatry. 2015;2:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott PA, Alterman AI, Brown LS, Zaballero A. Construct refinement and confirmation for the Addiction Severity Index. Psychol. Assess. 1996;8:182–189. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O’Brien CP, Kron R. Are the addiction-related problems of substance abusers really related? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1981;169:232–239. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argerious M. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Cacciola JC, Alterman AI, Rikoon SH, Carise C. The addiction severity index at 25 origins, contributions and transitions. Am. J. Addict. 2006;15:113–124. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Starrels JL, Tai B, Gordon AJ, Brown R, Ghitza U, Gourevitch M, Stein J, Oros M, Horton T, Lindblad R, McNeely J. Can substance use disorders be managed using the chronic care model? Review and recommendations from a NIDA consensus group. Public Health Rev. 2014;35 doi: 10.1007/BF03391707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melberg HO. Three problems with the ASI composite scores. J. Subst. Use. 2004;9:120–126. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. The prevention and treatment of missing data in clinical trials. In: Committee on National Statistics, D.o.B.a.S.S.a.E, editor. Panel on Handling Missing Data in Clinical Trials. The National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Navaline HA, Snider EC, Petro CJ, Tobin D, Metzger D, Alterman AI, Woody GE. Preparation for AIDS vaccine trials: an automated version of the Risk Assessment Battery. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1994;10:281–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the Timeline Followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014;28:154–162. doi: 10.1037/a0030992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Humana Press; New Jersey: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Friedman L, Greenfield SF, Hasin DS, Jackson R. Beyond drug use: a systematic consideration of other outcomes in evaluations of treatments for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2012;107:709–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR. The inventory of drug use consequences (InDUC): test-retest stability and sensitivity to detect change. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2002;16:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz JS, Cleaveland BL, Stephens RS. Problems in the application of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) in rural substance abuse services. J. Subst. Abuse. 1995;7:175–188. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winchell C, Rappaport BA, Roca R, Rosebraugh CJ. Reanalysis of methamphetamine dependence treatment trial. CNS Neurosci. Therap. 2012;18:367–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Quality of Life Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol. Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]