Abstract

Objective:

We characterized leading YouTube videos featuring alcohol brand references and examined video characteristics associated with each brand and video category.

Method:

We systematically captured the 137 most relevant and popular videos on YouTube portraying alcohol brands that are popular among underage youth. We used an iterative process to codebook development. We coded variables within domains of video type, character sociodemographics, production quality, and negative and positive associations with alcohol use. All variables were double coded, and Cohen’s kappa was greater than .80 for all variables except age, which was eliminated.

Results:

There were 96,860,936 combined views for all videos. The most common video type was “traditional advertisements,” which comprised 40% of videos. Of the videos, 20% were “guides” and 10% focused on chugging a bottle of distilled spirits. While 95% of videos featured males, 40% featured females. Alcohol intoxication was present in 19% of videos. Aggression, addiction, and injuries were uncommonly identified (2%, 3%, and 4%, respectively), but 47% of videos contained humor. Traditional advertisements represented the majority of videos related to Bud Light (83%) but only 18% of Grey Goose and 8% of Hennessy videos. Intoxication was most present in chugging demonstrations (77%), whereas addiction was only portrayed in music videos (22%). Videos containing humor ranged from 11% for music-related videos to 77% for traditional advertisements.

Conclusions:

YouTube videos depicting the alcohol brands favored by underage youth are heavily viewed, and the majority are traditional or narrative advertisements. Understanding characteristics associated with different brands and video categories may aid in intervention development.

Early initiation of alcohol consumption is associated with negative consequences such as other drug use, automobile accidents, development of chronic alcohol use disorders, violence, and early sexual activity and is the leading cause of premature death among adolescents and young adults (Connery et al., 2014; Hingson et al., 2002; Marshall, 2014; World Health Organization, 2016). Despite our understanding of the impact of alcohol use on adolescents, consumption remains high: U.S. nationally representative data indicate that 34.9% are current drinkers, defined as having a complete alcoholic drink during the past 30 days, and 20.8% of adolescents have consumed five alcoholic beverages within a couple of hours at least once in the past 30 days (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

Many sociodemographic, personal, and environmental factors are linked to alcohol use in adolescence and young adulthood (Marshall, 2014; McCambridge et al., 2011; Patrick & Schulenberg, 2013). However, exposures to alcohol in media messages are emerging as particularly important factors (Anderson et al., 2009; Hanewinkel et al., 2014; McClure et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2015). For example, youth are exposed to approximately 2–4 alcohol advertisements daily via various media outlets, including television and online sources (Collins et al., 2016) and about 35 references to alcohol use daily in popular music, and the vast majority of these messages associate alcohol use with social, sexual, and financial success (Primack et al., 2008, 2012).

Exposures to both narrative (e.g., movies and TV shows) and persuasive (e.g., advertisements and merchandising) media messages involving alcohol are associated with negative outcomes (Anderson et al., 2009; Engels et al., 2009; Grenard et al., 2013; McClure et al., 2009; Tanski et al., 2015). For example, watching popular music videos that contain content relating to alcohol use has been independently associated with earlier drinking onset, increased consumption, and decreases in the perceived risks of drunk driving (Beullens & van den Bulck, 2008; Robinson et al., 1998; van den Bulck & Beullens, 2005). Additionally, exposure to brand-specific advertisements is associated with increased consumption of popular brands (Ross et al., 2014), and that association has been found to be a dose–response relationship (Barry, 2016).

The combination of alcohol ad exposure and a positive affective reaction to those ads appears to influence some youth to subsequently drink and experience drinking-related problems to a greater extent (Grenard et al., 2013). Further, youth exposed to peers’ video content related to drinking and alcohol brands may develop more favorable norms and expectancies related to drinking and, ultimately, more alcohol use. Indeed, the associations between alcohol marketing and underage binge drinking have been found to be mediated by variables related to norms for peers being drunk, alcohol expectancies, having a favorite brand, and drinker identity (McClure et al., 2013).

Some of the fastest growing media exposures are Internet based (Barry et al., 2016; McClure et al., 2016). This is an important area for research because Internet access is widely available to youth, with 92% of teens reporting daily use (Lenhart, 2015). News reports indicate that alcohol industry digital media marketing spending has grown rapidly; but because digital media marketing is much less expensive than traditional marketing, the full impact of this growth is not shown in the percentage of the industry’s marketing budget spent on digital enterprises alone (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014). Youth are heavily exposed to alcohol online; for example, about 45% of YouTube videos to which adolescents are exposed contain alcohol imagery, and 7% of these videos contain alcohol branding (Cranwell et al., 2016).

Although many studies have investigated the effect of alcohol advertisements on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, little research has been done on video sharing platforms such as YouTube (Moreno & Whitehill, 2014). Video sharing platforms can combine the compelling high production values of traditional visual media with influential peer-to-peer dialogue (Huang et al., 2016; Oksanen et al., 2015). A 2014 study found that, of children who use the Internet, 85% had watched online video clips at least once during the previous month, compared with 76% who had used the Internet for schoolwork, and 71% who had visited a social networking profile (Mascheroni & Ólafsson, 2014). YouTube is currently the most popular video sharing site, with more than 1 billion unique users monthly. Furthermore, the frequency at which people access YouTube daily on the Internet has increased 40% per year for the past several years, and viewing videos on mobile devices recently increased year over year by 100% (YouTube, 2016).

Prior research has examined representations of alcohol intoxication on YouTube. This research helped elucidate the volume of exposure; for example, 70 systematically obtained videos related to alcohol intoxication had been viewed about a third of a billion times (Primack et al., 2015). This research also found that humor was juxtaposed with alcohol use in 79% of videos and that motor vehicle use was present in 24% of videos (Primack et al., 2015). Another study found that 44% of videos involved some type of alcohol brand appearance (ABA) (Primack et al., 2015). ABAs are important to assess because they may function as advertising, whether or not they are paid for or sanctioned by the alcohol industry (Primack et al., 2014). Furthermore, developing brand recognition is a crucial step in the marketing of any product, and companies attempt to create positive associations with their brands through product placement activities (Barry, 2016; Cranwell et al., 2015). Moreover, brand recognition and having a favorite brand are independent, potent risk factors for the initiation and maintenance of the use of these substances among adolescents (Henriksen et al., 2008; Volk et al., 1996).

Our first aim was to systematically obtain a set of YouTube videos that include ABAs for brands popular among youth. We focused on youth-oriented brands because of the value in intervening with this demographic. Second, we aimed to characterize the content of these ABA-containing videos. Finally, we aimed to determine what video characteristics were associated with each specific brand and each video type (e.g., advertisement vs. music video).

Method

Search algorithm and quality control

Based on previous research demonstrating brands of alcohol reported as favored and popular among underage drinkers (Siegel et al., 2013a; Tanski et al., 2011), as well as those appearing in popular music (Siegel et al., 2013b), we chose eight search strings reflecting a variety of brands across several types of alcoholic beverages. The brands were “Bud Light” (beer), “Coors Light” (beer), “Grey Goose” (vodka), “Hennessey” (cognac), “Jack Daniel’s” (whiskey), “Mike’s Hard Lemonade” (flavored alcohol drink), “Patron” (tequila), and “Smirnoff” (flavored alcohol and also vodka). We attempted to optimize each search term so as to improve sensitivity and specificity. For example, when we experimented with using “Jack Daniel” instead of “Jack Daniel’s,” there were a large number of false-positive results based on the name “Daniel.”

Video data were collected via the YouTube Application Programming Interface on September 19, 2013, and analyses were conducted through mid-2014. Our sample included all videos in the first 20 hits for each search, consistent with other studies in the area (Carroll et al., 2013; Gordon et al., 2001; Leighton & Srivastava, 1999; Madan et al., 2003; Primack et al., 2015). For each key term, we used this strategy under two separate conditions: (a) sorting videos by search term “relevance” according to YouTube’s internal algorithm and (b) sorting by “view count” to capture the most popular videos for each term. This was done to assess both content that is most commonly viewed as well as content that is most likely to come up in searches by youth (Carroll et al., 2013; Primack et al., 2015). This resulted in an initial pool of 320 videos (8 terms × 20 hits × 2 methods of sorting). There was little overlap in the video lists returned by the view count and relevance methods of sorting.

We then eliminated duplicate videos, defined as those in which more than half of the content or footage was identical (n = 81; 25%). We also eliminated irrelevant videos (n = 102; 32%), which we defined as those that did not contain any references to any type of alcohol brand. Videos in which English was not the primary language (i.e., more than half of the dialogue was in a non-English language) were excluded. After eliminating extraneous videos, there remained 137 videos to analyze for alcohol-related content. We expected this number of videos to be sufficient for content analysis based on prior similar work in this area (Carroll et al., 2013; Primack et al., 2015).

To ensure data integrity and facilitate analysis, we carefully retained appropriate video identification numbers and links as they were represented on the day of the search, as in Primack et al. (2015).

Codebook development

Codebook development followed general procedures established by Crabtree and Miller (1999) in their adaptation of qualitative research methods for health-oriented research. Three researchers with qualitative research experience independently examined 10 pilot videos and performed “in vivo” coding, which involved the development of descriptive codes based solely on the audiovisual material. Coders then met to discuss and compare their codes, adding, deleting, and collapsing codes together as necessary. Coders then coded a second series of 10 pilot videos with the new tentative codebook and met again to combine codes. This iterative process continued for four iterations until a final codebook was determined. To preserve the integrity of the final data set, pilot training videos were not part of the final sample.

This grounded theory approach was subsequently supplemented by existing theory-based information. It was appropriate to begin with grounded theory, which involves developing codes purely based on the data, in order to fully capture the richness of the data (Strauss & Corbin, 2007). We also felt it was important to add codes identified by prior content analyses related to media exposures and substance use (Forsyth & Malone, 2010; Gruber et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2010; Primack et al., 2012). For example, prior research based on Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2001) suggests that uptake of risky behaviors is increased when viewers are exposed to messages that juxtapose those behaviors with positive characteristics, such as humor and attractiveness (Bandura, 2001; Fischer et al., 2011). Therefore, although the initial codebook did not contain explicit assessment of humor and attractiveness, these variables were added for conceptual reasons. Similarly, we added variables describing alcohol-related behaviors known to be associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, such as active intoxication, injury, and dependence.

To finalize the codebook, all codes were operationally defined for clarity, conciseness, and relevance to the videos. Specific examples of each code were provided to improve reproducibility and clarity. The final codebook is available from the authors.

Coding procedures

We followed general coding procedures outlined in prior similar research (Carroll et al., 2013; Forsyth & Malone, 2010; Primack et al., 2015). Two trained coders worked independently to review and code the entire sample of videos. Training consisted of an ordered sequence of activities including didactic components and practice coding on other videos. Although other content analyses only include double coding for a small proportion of texts (Crabtree & Miller, 1999), we opted to double code all videos because this was feasible and because it improved the ultimate value of the data. For the variables coded, we computed interrater reliability, expressed in terms of Cohen’s κ (Cohen, 1960). Although nearly all coefficients were in the excellent range (κ > .80) in the final coding, coders’ impression of the age of participants was not reliable. Therefore, this variable was omitted from the analyses. For all other variables, coders and the principal investigator worked together to achieve consensus for the few disagreements that remained.

Measures

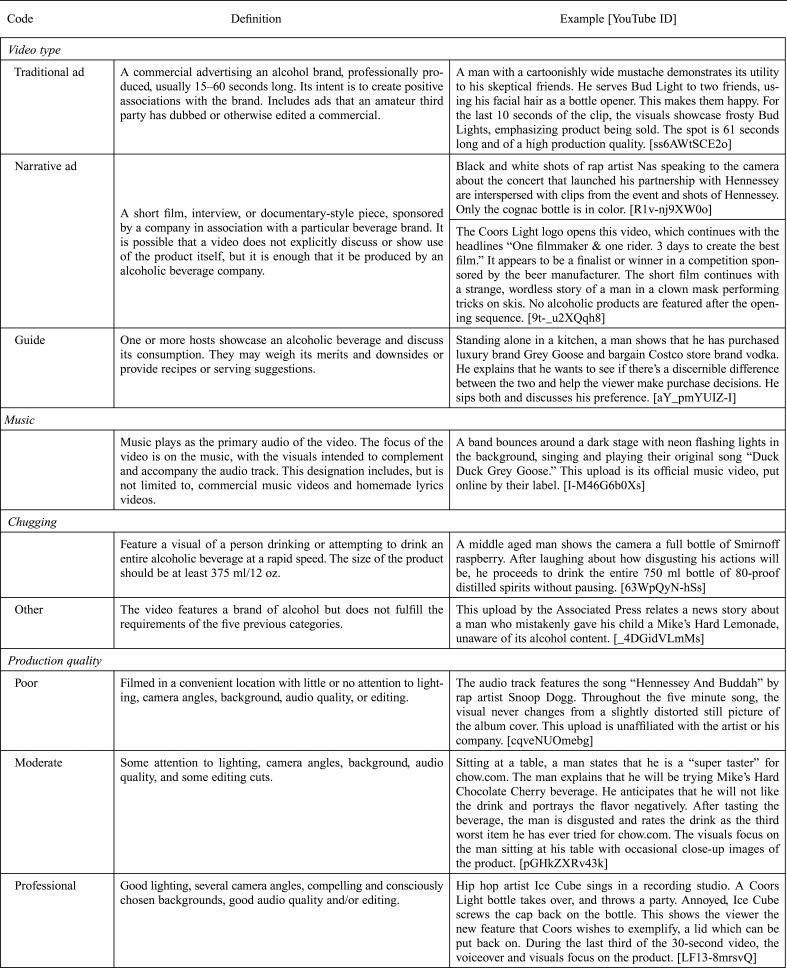

Our final codebook contained 21 codes that broadly represented five categories: video type, production quality, character sociodemographics, negative associations with alcohol use, and positive associations with alcohol use (Table 1).

Table 1.

Coding examples selected from the final sample of 137 videos

| Code | Definition | Example [YouTube ID] |

|

Video type

| ||

| Traditional ad | A commercial advertising an alcohol brand, professionally produced, usually 15–60 seconds long. Its intent is to create positive associations with the brand. Includes ads that an amateur third party has dubbed or otherwise edited a commercial. | A man with a cartoonishly wide mustache demonstrates its utility to his skeptical friends. He serves Bud Light to two friends, using his facial hair as a bottle opener. This makes them happy. For the last 10 seconds of the clip, the visuals showcase frosty Bud Lights, emphasizing product being sold. The spot is 61 seconds long and of a high production quality. [ss6AWtSCE2o] |

| Narrative ad | A short film, interview, or documentary-style piece, sponsored by a company in association with a particular beverage brand. It is possible that a video does not explicitly discuss or show use of the product itself, but it is enough that it be produced by an alcoholic beverage company. | Black and white shots of rap artist Nas speaking to the camera about the concert that launched his partnership with Hennessey are interspersed with clips from the event and shots of Hennessey. Only the cognac bottle is in color. [R1v-nj9XW0o] |

| The Coors Light logo opens this video, which continues with the headlines “One filmmaker & one rider. 3 days to create the best film.” It appears to be a finalist or winner in a competition sponsored by the beer manufacturer. The short film continues with a strange, wordless story of a man in a clown mask performing tricks on skis. No alcoholic products are featured after the opening sequence. [9t-_u2XQqh8] | ||

| Guide | One or more hosts showcase an alcoholic beverage and discuss its consumption. They may weigh its merits and downsides or provide recipes or serving suggestions. | Standing alone in a kitchen, a man shows that he has purchased luxury brand Grey Goose and bargain Costco store brand vodka. He explains that he wants to see if there’s a discernible difference between the two and help the viewer make purchase decisions. He sips both and discusses his preference. [aY_pmYUIZ-I] |

|

Music

| ||

| Music plays as the primary audio of the video. The focus of the video is on the music, with the visuals intended to complement and accompany the audio track. This designation includes, but is not limited to, commercial music videos and homemade lyrics videos. | A band bounces around a dark stage with neon flashing lights in the background, singing and playing their original song “Duck Duck Grey Goose.” This upload is its official music video, put online by their label. [I-M46G6b0Xs] | |

|

Chugging

| ||

| Feature a visual of a person drinking or attempting to drink an entire alcoholic beverage at a rapid speed. The size of the product should be at least 375 ml/12 oz. | A middle aged man shows the camera a full bottle of Smirnoff raspberry. After laughing about how disgusting his actions will be, he proceeds to drink the entire 750 ml bottle of 80-proof distilled spirits without pausing. [63WpQyN-hSs] | |

| Other | The video features a brand of alcohol but does not fulfill the requirements of the five previous categories. | This upload by the Associated Press relates a news story about a man who mistakenly gave his child a Mike’s Hard Lemonade, unaware of its alcohol content. [_4DGidVLmMs] |

|

Production quality

| ||

| Poor | Filmed in a convenient location with little or no attention to lighting, camera angles, background, audio quality, or editing. | The audio track features the song “Hennessey And Buddah” by rap artist Snoop Dogg. Throughout the five minute song, the visual never changes from a slightly distorted still picture of the album cover. This upload is unaffiliated with the artist or his company. [cqveNUOmebg] |

| Moderate | Some attention to lighting, camera angles, background, audio quality, and some editing cuts. | Sitting at a table, a man states that he is a “super taster” for chow.com. The man explains that he will be trying Mike’s Hard Chocolate Cherry beverage. He anticipates that he will not like the drink and portrays the flavor negatively. After tasting the beverage, the man is disgusted and rates the drink as the third worst item he has ever tried for chow.com. The visuals focus on the man sitting at his table with occasional close-up images of the product. [pGHkZXRv43k] |

| Professional | Good lighting, several camera angles, compelling and consciously chosen backgrounds, good audio quality and/or editing. | Hip hop artist Ice Cube sings in a recording studio. A Coors Light bottle takes over, and throws a party. Annoyed, Ice Cube screws the cap back on the bottle. This shows the viewer the new feature that Coors wishes to exemplify, a lid which can be put back on. During the last third of the 30-second video, the voiceover and visuals focus on the product. [LF13-8mrsvQ] |

|

Negative associations with alcohol use

| ||

| Aggression | Aggressive behavior noted in a “serious” context. | Blurry footage shot at a party event sponsored by Ciroc. The rapper Diddy can be heard shouting profanity at one of the guests for drinking competitor product Grey Goose. He repeatedly yells phrases including “Put that shit down!” and “Get the fuck out of here!” The guest responds with similar language and tone. [V5FDh5v9whY] |

| Addiction | Specific reference to being a “drunk” or an “addict,” depiction of physical tolerance or withdrawal, or similar language or representation. | Country music singer Chase Rice’s picture shows throughout the video, with the audio featuring his song “Jack Daniel’s and Jesus.” Lyrics include “It’s my fault that I ain’t called my momma in a month of Sundays. She’ll smell the whiskey through that phone. I can’t stand to hear her heartbreak.” [sCNQPPcY3us] |

| Intoxication | Apparent slurring of speech, awkwardness of movement, reduction of social inhibitions, or other signs of acute intoxication. | A promotional video from the Smirnoff Ice Summer Tour. This was filmed during a tour stop in Venezuela. People dance and party with cups in their hands. The dancing becomes wilder as the video continues. The escalating inebriation is additionally evident as people yell and cheer, drop drinks, and splash each other in pools. [mV9vL4hozoU] |

| Injury | An injury that might require a hospital or physician visit. | A woman believes her date has a stripper pole in his living room. She begins to dance around it. In reality, it is a fireman’s pole that allows upstairs neighbors to quickly descend in search of Bud Light. One such neighbor lands directly on her head, knocking her to the ground. At the end of the commercial, a second neighbor lands on the first, repeating the injurious physical comedy. [pc-V4K1-bQc] |

| This beer advertisement features a preppy man showing off his pure-bred dog. He directs the pet to retrieve a Bud Light from a cooler. In response, an average man commands his mutt to do the same. The dog responds by biting the preppy man’s crotch, causing him to throw his bottle of Bud Light to the mutt’s owner. [NFg3HBMJyV4] | ||

| Vehicle use | A member of the focal group comes in physical contact with a motor vehicle. | The lyrics to the featured song, “I’m on Patron,” mention vehicles multiple times. The chorus repeats “I’m gone, so gone, so throwed, can I get a ride home,” indicating that the narrator is too inebriated to operate an automobile. The lyric “If I get pulled over TV Jonny pay my bond” suggests he may decide to drive regardless. [1jX2XeL4lYU] |

| In this 30-second Smirnoff spot, the model Amber Rose visits two parties. Their theming suggests first Smirnoff Fluffed, then Smirnoff Whipped. To facilitate transportation between the glamorous events, she is chauffeured in a retro car. The happy, laughing protagonist rides accompanied by two more glamorous persons. [kIgaNxbR6zQ] | ||

|

Positive associations with alcohol use

| ||

| Humor | Containing content likely humorous to the intended audience.a | A man asks a squirrel to guard his Bud Light. As soon as he walks away, his friend tries to drink the beverage. The squirrel jumps on the thief’s face and punches him with tiny fists. The short ad contains both physical and verbal gags. [kiTarkl31Gw] |

| Attractiveness | Containing people likely to be physically attractive to the intended audience.a | Musical artist Trina sings and dances in her music video. She is slim with a curvy figure, high cheek bones, and full lips. She wears makeup and is dressed to accentuate her attractive physical qualities. [OTMlvJLAMCk] |

Notes: Character sociodemographics were also noted; these are not listed in this table because descriptions were not necessary. aIntended audience is conceptualized as a typical U.S. adolescent.

Video type.

Six mutually exclusive categories represented traditional advertisement, narrative advertisement, guide, music, chugging, and other. During the iterative code development process, the explicit decision was made for this category to be a mutually exclusive categorical variable instead of multiple dichotomous variables. This was done because the data naturally fell into mutually exclusive categories with very little overlap.

Production quality.

Production quality was assessed as poor, moderate, or professional. This was deemed as an important variable to capture because it was noted during the grounded theory process and because the perception of the “professional” nature of a video can add to its influence.

Character sociodemographics.

This category included five dichotomous variables that captured sex and race/ethnicity. Coders focused on primary individuals, defined as those individuals pictured in an active role in the video, such as speaking, performing music, or interacting directly with a speaker or performer. Binary variables enabled coders to describe pictured individuals as male or female and White or Black; because there were so few characters that could be clearly identified as Hispanic or Latino, Asian or Pacific Islander, or Native American, these categories were combined into “other race/ethnicity.”

Categories were not mutually exclusive because a video might picture both females and males and individuals of multiple racial and/or ethnic groups.

Negative associations with alcohol use.

This category contained five dichotomous codes, as follows: aggression, addiction, intoxication, injury, and vehicle use.

Positive associations with alcohol use.

Two dichotomous codes indicated whether alcohol was associated with the positive characteristics of humor and attractiveness. Because these factors can be subjective, these were defined as likely to be humorous or attractive to the typical adolescent viewer, the intended audience of the video.

Analysis

Because the purpose of this study was a content analysis, our analyses focused on quantitative descriptive data and qualitative representative examples of each of the codes. We first assessed each of the video characteristics according to the specific brand of the video’s focus. We also examined coded video characteristics for each of the video types (e.g., traditional advertisement, narrative advertisement, guide). Because all variables were categorical or dichotomous, we used chi-square tests (α = .05; two tailed) to define statistical significance. Tests were conducted using Stata Version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Sample

The 137 videos lasted a median of 129 (interquartile range [IQR] = 61–258) seconds. Each video had been viewed a median of 116,650 (IQR = 12,377–384,973) times, for a total of 96,860,936 views for all videos combined. Included videos were published to YouTube between February 4, 2006, and September 10, 2013. The number of days a video had been online before data collection view count was associated with view count (r = .31) and “dislikes” (r = .21) but not “likes” (r = .04). The videos had a median of 302 (IQR = 44–1027) “like” designations and 11 (IQR = 2–81) “dislike” designations each.

Code frequencies

The most common video type was “traditional advertisements,” which comprised 40% (n = 55) of videos. “Narrative advertisements” comprised 12% (n = 16) of the sample. One fifth (20%) of videos were classified as “guides” (n = 27), and 13% (n =18) were classified as primarily music related. Ten percent (n = 14) of videos were “chugging” demonstration videos, and only 7 videos did not fall into any of these categories.

The majority of videos (61%, n = 84) were classified as professional in terms of production quality. About one fourth (26%, n = 36) were classified as poor, and the remaining 12% (n = 17) were classified as moderate.

While 95% (n = 130) of videos featured males, only 40% (n = 55) featured females. Further, 77% of videos (n = 106) depicted White individuals, 34% (n = 46) depicted Black individuals, and 12% (n = 16) depicted individuals within other racial/ethnic categories (e.g., Hispanic and Asian).

Alcohol intoxication was apparent in 19% (n = 26) of videos, but addiction was only coded in 3% (n = 4) of videos. Aggression and injuries were uncommonly identified (2% and 4%, respectively). Motor vehicle use was coded in 8% (n = 11) of videos. Nearly half (47%, n = 65) of videos contained humor, and 31% (n = 42) were classified as including attractive primary characters.

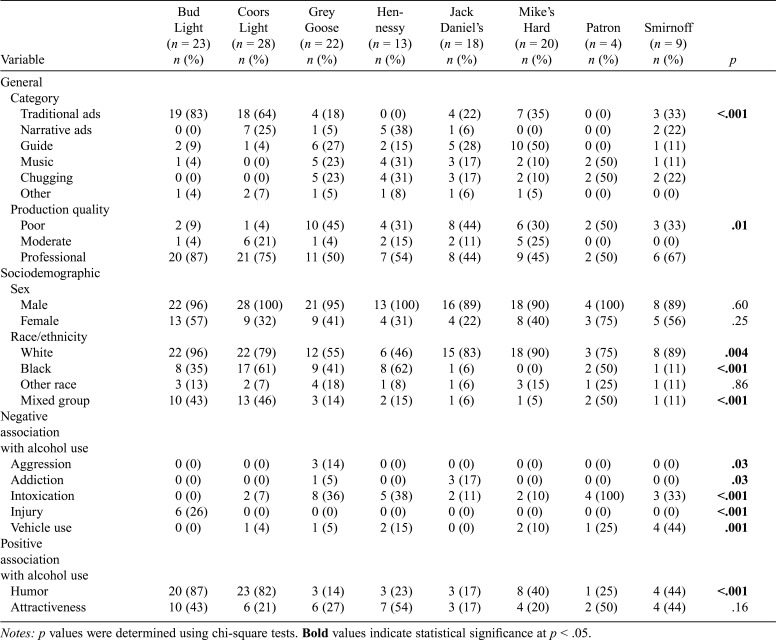

Associations between video characteristics and brands

There were significant differences in the category of video according to each specific brand referenced (p < .001; Table 2). For example, 83% of videos related to Bud Light were traditional advertisements, but only 18% of Grey Goose videos and none of the Patron videos were traditional advertisements.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 137 YouTube videos according to brand

| Variable | Bud Light (n = 23) n (%) | Coors Light (n = 28) n (%) | Grey Goose (n = 22) n (%) | Hennessy (n =13) n (%) | Jack Daniel’s (n = 18) n (%) | Mike’s Hard (n = 20) n (%) | Patron (n = 4) n (%) | Smirnoff (n = 9) n (%) | p |

| General Category | |||||||||

| Category | |||||||||

| Traditional ads | 19 (83) | 18 (64) | 4(18) | 0 (0) | 4 (22) | 7 (35) | 0 (0) | 3 (33) | <.001 |

| Narrative ads | 0(0) | 7 (25) | 1 (5) | 5 (38) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | |

| Guide | 2 (9) | 1 (4) | 6 (27) | 2 (15) | 5 (28) | 10 (50) | 0 (0) | 1(11) | |

| Music | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 5 (23) | 4(31) | 3 (17) | 2 (10) | 2 (50) | 1(11) | |

| Chugging | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (23) | 4(31) | 3 (17) | 2 (10) | 2 (50) | 2 (22) | |

| Other | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | 1 (5) | 1 (8) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Production quality | |||||||||

| Poor | 2 (9) | 1 (4) | 10 (45) | 4(31) | 8 (44) | 6 (30) | 2 (50) | 3 (33) | .01 |

| Moderate | 1 (4) | 6(21) | 1 (4) | 2 (15) | 2 (11) | 5 (25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Professional | 20 (87) | 21 (75) | 11 (50) | 7 (54) | 8 (44) | 9 (45) | 2 (50) | 6 (67) | |

| Sociodemographic Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 22 (96) | 28 (100) | 21 (95) | 13 (100) | 16 (89) | 18 (90) | 4(100) | 8 (89) | .60 |

| Female | 13 (57) | 9 (32) | 9(41) | 4(31) | 4 (22) | 8 (40) | 3 (75) | 5 (56) | .25 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 22 (96) | 22 (79) | 12 (55) | 6 (46) | 15 (83) | 18 (90) | 3 (75) | 8 (89) | .004 |

| Black | 8 (35) | 17 (61) | 9(41) | 8 (62) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | 1(11) | <.001 |

| Other race | 3(13) | 2 (7) | 4(18) | 1 (8) | 1 (6) | 3 (15) | 1 (25) | 1(11) | .86 |

| Mixed group | 10 (43) | 13 (46) | 3(14) | 2(15) | 1 (6) | 1 (5) | 2 (50) | 1(11) | <.001 |

| Negative association with alcohol use | |||||||||

| Aggression | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3(14) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .03 |

| Addiction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .03 |

| Intoxication | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | 8 (36) | 5 (38) | 2 (11) | 2 (10) | 4(100) | 3 (33) | <.001 |

| Injury | 6 (26) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Vehicle use | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 2(15) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 1 (25) | 4 (44) | .001 |

| Positive association with alcohol use | |||||||||

| Humor | 20 (87) | 23 (82) | 3(14) | 3 (23) | 3 (17) | 8 (40) | 1 (25) | 4 (44) | <.001 |

| Attractiveness | 10 (43) | 6(21) | 6 (27) | 7(54) | 3 (17) | 4 (20) | 2 (50) | 4 (44) | .16 |

Notes: p values were determined using chi-square tests. Bold values indicate statistical significance at p < .05.

Production quality was also significantly associated with brand (p < .01). For example, more Bud Light videos were in the professional production category compared with Jack Daniel’s (87% vs. 44%).

White and Black race were significantly associated with brand. However, there were no differences with regard to gender and the other race/ethnicity category.

We found significant associations between each of the negative alcohol characteristics and brand. For example, all Patron videos but none of the Bud Light videos portrayed intoxication. Intoxication among other brands ranged from 7% to 38% of videos. Only Grey Goose and Jack Daniel’s videos were coded as referring to addiction or dependence (5% and 17%, respectively). Only Grey Goose videos portrayed aggressive behaviors (14%), and only Bud Light videos were coded as containing injuries (26%). Last, the proportion of videos with vehicle use ranged from 0% for Bud Light and Jack Daniel’s to 44% for Smirnoff.

For positive associations, the majority of Bud Light and Coors Light videos featured humor (87% and 82%, respectively), whereas brands such as Grey Goose and Jack Daniel’s were less likely to contain humor (14% and 17%, respectively). There was no significant association between the portrayal of attractiveness and the specific brand mentioned.

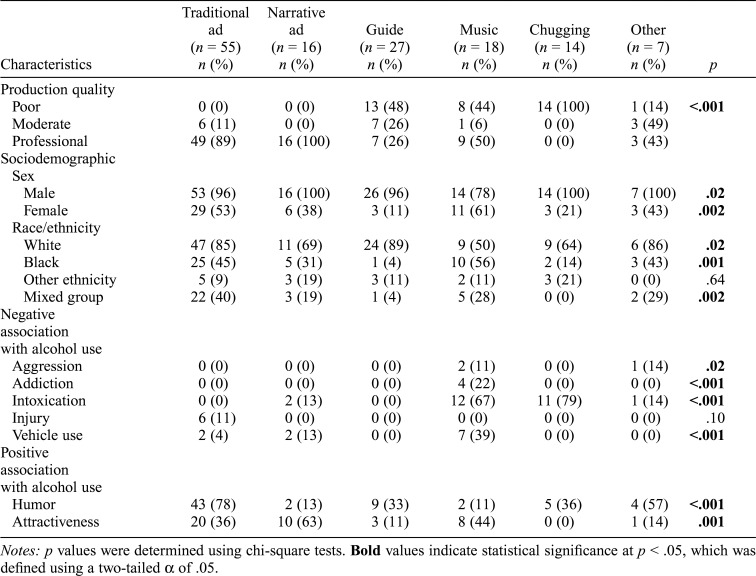

Associations between video characteristics and video types

Significant associations exist between negative alcohol characteristics and video categories (Table 3). For example, intoxication was most present in chugging demonstrations (79%), whereas addiction was only portrayed in music-related videos (22%). Similarly, aggression and vehicle use were most likely to appear in videos categorized for music (11% and 39%, respectively). There was no significant association between the presence of injury and video category.

Table 3.

Characteristics of 137 YouTube videos according to video type

| Characteristics | Traditional ad (n = 55) n (%) | Narrative ad (n = 16) n (%) | Guide (n = 27) n (%) | Music (n = 18) n (%) | Chugging (n = 14) n (%) | Other (n = 7) n (%) | P |

| Production quality | |||||||

| Poor | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (48) | 8 (44) | 14 (100) | 1 (14) | <.001 |

| Moderate | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 7 (26) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (49) | |

| Professional | 49 (89) | 16 (100) | 7 (26) | 9 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | |

| Sociodemographic Sex | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 53 (96) | 16 (100) | 26 (96) | 14 (78) | 14 (100) | 7 (100) | .02 |

| Female | 29 (53) | 6 (38) | 3 (11) | 11 (61) | 3 (21) | 3 (43) | .002 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 47 (85) | 11 (69) | 24 (89) | 9 (50) | 9 (64) | 6 (86) | .02 |

| Black | 25 (45) | 5 (31) | 1 (4) | 10 (56) | 2 (14) | 3 (43) | .001 |

| Other ethnicity | 5 (9) | 3 (19) | 3 (11) | 2 (11) | 3 (21) | 0 (0) | .64 |

| Mixed group | 22 (40) | 3 (19) | 1 (4) | 5 (28) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | .002 |

| Negative association with alcohol use | |||||||

| Aggression | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | .02 |

| Addiction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Intoxication | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 12 (67) | 11 (79) | 1 (14) | <.001 |

| Injury | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | .10 |

| Vehicle use | 2 (4) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 7 (39) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| Positive association with alcohol use | |||||||

| Humor | 43 (78) | 2 (13) | 9 (33) | 2 (11) | 5 (36) | 4 (57) | <.001 |

| Attractiveness | 20 (36) | 10 (63) | 3 (11) | 8 (44) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | .001 |

Notes: p values were determined using chi-square tests. Bold values indicate statistical significance at p < .05, which was defined using α two-tailed a of .05.

We identified significant associations between both of the positive alcohol characteristics and video categories. Videos containing humor ranged from 11% for music-related videos to 78% for traditional advertisements (Table 3). Finally, attractiveness was most prevalent in narrative advertisements (63%).

Discussion

It is noteworthy that videos such as these have been viewed so many times. One implication of this is that this medium provides an alternative for companies that seek exposure to their brands outside of usual venues such as billboards, television advertisements, and event sponsorships. Although the vast majority of the videos retrieved were not uploaded by companies themselves, corporate entities may still have influenced the content and/or placement of these messages. For example, alcohol companies sponsor concerts, parties, and music videos (Siegel et al., 2013b).

The most common videos were traditional advertisements. However, these videos were not uploaded by companies themselves. Instead, they were posted by ordinary users and usually featured humor. This finding suggests that social media tends to amplify many of the persuasive messages created and promoted by the alcohol industry. In addition, because the reposted advertisements represent peer-to-peer communication—as opposed to industry-to-peer communication—they may be particularly influential.

Fully 10% of the videos featured a man chugging a full bottle of distilled spirits. In each case, he took careful pains to demonstrate that there was no trick photography by clearly opening the sealed bottle and then immediately drinking the entire contents in 22 seconds. In one video with more than 650,000 views and more than 4,000 “like” designations, the host chugged vodka (750 ml of 40% alcohol) in less than 30 seconds while in an inpatient rehabilitation unit for alcoholism. Impressionable youth viewing these videos may develop maladaptive attitudes regarding factors such as the immediate dangers of binge drinking and the seriousness of rehabilitation.

All videos portrayed the presence of at least one human being. Whereas 95% of videos featured males, only about half of videos portrayed females, consistent with prior research. One reason for this disparity may be simply because males exhibit more frequent episodic drinking relative to females (Chavez et al., 2011). Another possibility is that alcohol use is generally perceived as more socially acceptable for males (de Visser & McDonnell, 2012). Because more males are featured, future interventions debunking alcohol-related myths propagated on social media may be useful to target toward males.

We noted a wide variation between negative and positive aspects of alcohol use; whereas only 2%–4% of videos portrayed aggression, addiction, or injuries, about half of videos portrayed humor. This is a common pattern in media portrayals, because producers often like to emphasize the fun, compelling aspects of alcohol use while downplaying the serious consequences that may be unappealing to users (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014; Primack et al., 2015; Robinson et al., 1998). Nearly all of the negativity was seen in music videos, some of which tend to portray “gritty” aspects of reality to increase affect. However, overall levels of negativity were still very low; for example, only 2 of 18 music videos portrayed aggression and only 4 of 18 portrayed addiction.

We noted that each brand was associated with a distinct set of characteristics. For example, all Patron videos but none of the Bud Light videos portrayed intoxication. This may have been because Patron videos were almost all music videos in which individuals were drinking excessively, whereas Bud Light videos were generally advertisements in which beer was being linked to a fun, friendly, humorous lifestyle. In these situations, portraying intoxication may have been limited by alcohol industry self-regulation codes. For example, the Beer Institute (2015) and Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (2011) codes contain social responsibility clauses stating that alcohol advertising should not depict excessive or irresponsible drinking. It should be noted, however, that the alcohol industry is not always faithful to its own guidelines (Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, 2004).

In 2012, YouTube added an “Age Gate” to block inappropriate content from underage users (Barry et al., 2015). However, official alcohol companies’ YouTube channels are still highly accessible to underage youth (Barry et al., 2015). It is also important to note that in the present study the advertisement videos were not all posted by the alcohol company; some were shared by other users.

Another example of distinct brand associations was that the majority of Bud Light and Coors Light videos featured humor (87% and 82%, respectively), whereas brands such as Grey Goose and Jack Daniel’s were much less likely to contain humor (14% and 17%, respectively). Beer brands often used advertisements as a distinctive tactic to connect their product with humor (Jernigan & Rushman, 2014; Primack et al., 2015).

Limitations

We collected our videos at only one point in time. We tried to minimize this limitation by sampling according to both popularity and relevance, but we acknowledge that our results may not be generalizable to other samples of user generated and posted videos. Although the selected videos reflect brands popular at the time of collection, alcohol preference among underage youth varies over time. Similarly, the selected brands may not be generalizable to brands outside of the scope of this investigation.

Another necessary limitation is that subjectivity is inherent in the coding of variables such as production quality, humor, and attractiveness. Although we took steps to minimize this concern—such as developing a comprehensive codebook with detailed criteria and double coding—this remains a potential limitation.

Caution should be exercised concerning certain figures, such as the view count, provided by YouTube. For example, this count does not represent unique users, and it does not distinguish between U.S. and international users. It was also beyond the scope of this study to examine the comments associated with each of the primary videos. Although it is appropriate at this early stage of research to begin with the primary videos, it will be exciting for future research to delve into the potentially rich discussion around these primary videos.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, our work suggests that Internet videos depicting alcohol brands have been heavily viewed, generally represent traditional advertisements reposted by users, often include humor, and infrequently depict negative consequences of alcohol use. The stark differences between the representation of alcohol brands on YouTube and true known clinical associations with alcohol use may provide an opportunity for educational interventions. Finally, understanding the ways that specific brands are portrayed may help public health practitioners develop tailored interventions based on brands, which are associated with strong loyalty by consumers in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research. We thank Michelle Woods for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

This research was supported by ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research.

References

- Anderson P., de Bruijn A., Angus K., Gordon R., Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol and Alcoholism . 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology . 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. E. Alcohol advertising influences underage brand-specific drinking: Evidence of a linear dose-response relationship. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse . 2016;42:1–3. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1104319. doi:10.3109/00952990.2015.1104319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. E., Bates A. M., Olusanya O., Vinal C. E., Martin E., Peoples J. E., Montano J. R. Alcohol marketing on Twitter and Instagram: Evidence of directly advertising to youth/adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism . 2016;51:487–492. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv128. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. E., Johnson E., Rabre A., Darville G., Donovan K. M., Efunbumi O. Underage access to online alcohol marketing content: A YouTube case study. Alcohol and Alcoholism . 2015;50:89–94. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu078. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agu078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer Institute. Washington, DC: Author; 2015. Advertising and marketing code . Retrieved from http://www.beerinstitute.org/assets/uploads/general-upload/2015-Beer-Ad-Code-Brochure.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Beullens K., Van den Bulck J. News, music videos and action movie exposure and adolescents’ intentions to take risks in traffic. Accident Analysis and Prevention . 2008;40:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.07.002. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M. V., Shensa A., Primack B. A. A comparison of cigarette-and hookah-related videos on YouTube. Tobacco Control . 2013;22:319–323. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050253. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth. Washington DC: Author; 2004. Clicking with kids: Alcohol marketing and youth on the internet . Retrieved from http://www.camy.org/_docs/resources/reports/archived-reports/clicking-with-kids-exec-sum.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the prevalence of alcohol use: National YRBS: 1991–2013 . 2016. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trends/us_alcohol_trend_yrbs.pdf .

- Chavez P. R., Nelson D. E., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D. Impact of a new gender-specific definition for binge drinking on prevalence estimates for women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine . 2011;40:468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement . 1960;20:37–46. doi:10.1177/001316446002000104. [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. L., Martino S. C., Kovalchik S. A., Becker K. M., Shadel W. G., D’Amico E. J. Alcohol advertising exposure among middle school-age youth: An assessment across all media and venues. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs . 2016;77:384–392. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.384. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connery H. S., Albright B. B., Rodolico J. M. Adolescent substance use and unplanned pregnancy: Strategies for risk reduction. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America . 2014;41:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.02.011. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree B. F., Miller W. L. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. Doing qualitative research . [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell J., Murray R., Lewis S., Leonardi-Bee J., Dockrell M., Britton J. Adolescents’ exposure to tobacco and alcohol content in YouTube music videos. Addiction . 2015;110:703–711. doi: 10.1111/add.12835. doi:10.1111/add.12835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell J., Opazo-Breton M., Britton J. Adult and adolescent exposure to tobacco and alcohol content in contemporary YouTube music videos in Great Britain: A population estimate. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health . 2016;70:488–492. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206402. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser R. O., McDonnell E. J. That’s OK. He’s a guy: A mixed-methods study of gender double-standards for alcohol use. Psychology & Health . 2012;27:618–639. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.617444. doi:10.1080/08870446.2011.617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distilled Spirits Council of the United States. Washington DC . Author; 2011. Code of responsible practices for beverage alcohol advertising and marketing . Retrieved from http://www.discus.org/assets/1/7/May_26_2011_DISCUS_Code_Word_Version1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Engels R. C. M. E., Hermans R., van Baaren R. B., Hollenstein T., Bot S. M. Alcohol portrayal on television affects actual drinking behaviour. Alcohol and Alcoholism . 2009;44:244–249. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp003. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P., Greitemeyer T., Kastenmuller A., Vogrincic C., Sauer A. The effects of risk-glorifying media exposure on risk-positive cognitions, emotions, and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin . 2011;137:367–390. doi: 10.1037/a0022267. doi:10.1037/a0022267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth S. R., Malone R. E. “I’ll be your cigarette—light me up and get on with it”: Examining smoking imagery on YouTube. Nicotine & Tobacco Research . 2010;12:810–816. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq101. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. B., Barot L. R., Fahey A. L., Matthews M. S. The Internet as a source of information on breast augmentation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery . 2001;107:171–176. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200101000-00028. doi:10.1097/00006534-200101000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard J. L., Dent C. W., Stacy A. W. Exposure to alcohol advertisements and teenage alcohol-related problems. Pediatrics . 2013;131:e369–e379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1480. doi:10.1542/peds.2012–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E. L., Thau H. M., Hill D. L., Fisher D. A., Grube J. W. Alcohol, tobacco and illicit substances in music videos: A content analysis of prevalence and genre. Journal of Adolescent Health . 2005;37:81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.034. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R., Sargent J. D., Hunt K., Sweeting H., Engels R. C. M. E., Scholte R. H. J, Morgenstern M. Portrayal of alcohol consumption in movies and drinking initiation in low-risk adolescents. Pediatrics . 2014;133:973–982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3880. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L., Feighery E. C., Schleicher N. C., Fortmann S. P. Receptivity to alcohol marketing predicts initiation of alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health . 2008;42:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.005. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R., Heeren T., Levenson S., Jamanka A., Voas R. Age of drinking onset, driving after drinking, and involvement in alcohol related motor-vehicle crashes. Accident Analysis and Prevention . 2002;34:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(01)00002-1. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(01)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Kornfield R., Emery S. L. 100 million views of electronic cigarette YouTube videos and counting: Quantification, content evaluation, and engagement levels of videos. Journal of Medical Internet Research . 2016;18:e67. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4265. doi:10.2196/jmir.4265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D. H., Rushman A. E. Measuring youth exposure to alcohol marketing on social networking sites: Challenges and prospects. Journal of Public Health Policy . 2014;35:91–104. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.45. doi:10.1057/jphp.2013.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Paek H. J., Lynn J. A content analysis of smoking fetish videos on YouTube: Regulatory implications for tobacco control. Health Communication . 2010;25:97–106. doi: 10.1080/10410230903544415. doi:10.1080/10410230903544415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton H. V, Srivastava J. First 20 precision among World Wide Web search services (search engines) Journal of the American Society for Information Science . 1999;50:870–881. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097–4571(1999)50:10<870::AID-ASI4>3.0.CO;2-G. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. Teens, social media & technology overview 2015: Smartphones facilitate shifts in communication landscape for teens . Pew Research Center . 2015 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/09/teens-social-media-technology-2015/ [Google Scholar]

- Madan A. K., Frantzides C. T., Pesce C. E. The quality of information about laparoscopic bariatric surgery on the Internet. Surgical Endoscopy . 2003;17:685–687. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8610-7. doi:10.1007/s00464-002-8610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E. J. Adolescent alcohol use: Risks and consequences. Alcohol and Alcoholism . 2014;49:160–164. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt180. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agt180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascheroni G., Ólafsson K. 2014. Net children go mobile: Risks and opportunities 2nd ed. Milan, Italy: Educatt. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.3590.8561 [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J., McAlaney J., Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: A systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Medicine . 2011;8(2):e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413. doi:10.1371/journal. pmed.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Stoolmiller M., Tanski S. E., Engels R. C. M. E., Sargent J. D. Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing-specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2013;37(Supplement 1):E404–E413. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Stoolmiller M., Tanski S. E., Worth K. A., Sargent J. D. Alcohol-branded merchandise and its association with drinking attitudes and outcomes in US adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine . 2009;163:211–217. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.554. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure A. C., Tanski S. E., Li Z., Jackson K., Morgenstern M., Li Z., Sargent J. D. Internet alcohol marketing and underage alcohol use. Pediatrics . 2016;137(2):e20152149. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2149. doi:10.1542/peds.2015–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M. A., Whitehill J. M. Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews . 2014;36:91–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen A., Garcia D., Sirola A., Nasi M., Kaakinen M., Keipi T., Räsänen P. Pro-anorexia and anti-pro-anorexia videos on YouTube: Sentiment analysis of user responses. Journal of Medical Internet Research . 2015;17(11):e256. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5007. doi:10.2196/jmir.5007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Schulenberg J. E. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews . 2013;35:193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., Colditz J. B., Pang K. C., Jackson K. M. Portrayal of alcohol intoxication on YouTube. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2015;39:496–503. doi: 10.1111/acer.12640. doi:10.1111/acer.12640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., Dalton M. A., Carroll M. V., Agarwal A. A., Fine M. J. Content analysis of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs in popular music. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine . 2008;162:169–175. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., McClure A. C., Li Z., Sargent J. D. Receptivity to and recall of alcohol brand appearances in U.S. popular music and alcohol-related behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2014;38:1737–1744. doi: 10.1111/acer.12408. doi:10.1111/acer.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., Nuzzo E., Rice K. R., Sargent J. D. Alcohol brand appearances in US popular music. Addiction . 2012;107:557–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03649.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. P., Siegel M. B., DeJong W., Ross C. S., Naimi T., Albers A., Jernigan D. H. Brands matter: Major findings from the Alcohol Brand Research Among Underage Drinkers (ABRAND) project. Addiction Research & Theory . 2015;24:32–39. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2015.1051039. doi:10.3109/16066359.2015.1051039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T. N., Chen H. L., Killen J. D. Television and music video exposure and risk of adolescent alcohol use. Pediatrics . 1998;102(5):e54. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.5.e54. doi:10.1542/peds.102.5.e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. S., Maple E., Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Ostroff J., Jernigan D. H. The relationship between brand-specific alcohol advertising on television and brand-specific consumption among underage youth. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2014;38:2234–2242. doi: 10.1111/acer.12488. doi:10.1111/acer.12488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M., DeJong W., Naimi T. S., Fortunato E. K., Albers A. B., Heeren T., Jernigan D. H. Brand-specific consumption of alcohol among underage youth in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research . 2013a;37:1195–1203. doi: 10.1111/acer.12084. doi:10.1111/acer.12084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel M., Johnson R. M., Tyagi K., Power K., Lohsen M. C., Ayers A. J., Jernigan D. H. Alcohol brand references in U.S. popular music, 2009–2011. Substance Use & Misuse . 2013b;48:1475–1484. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.793716. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.793716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A., Corbin J. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . [Google Scholar]

- Tanski S. E., McClure A. C., Jernigan D. H., Sargent J. D. Alcohol brand preference and binge drinking among adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine . 2011;165:675–676. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.113. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanski S. E., McClure A. C., Li Z., Jackson K., Morgenstern M., Li Z., Sargent J. D. Cued recall of alcohol advertising on television and underage drinking behavior. JAMA Pediatrics . 2015;169:264–271. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3345. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulck J., Beullens K. Television and music video exposure and adolescent alcohol use while going out. Alcohol and Alcoholism . 2005;40:249–253. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh139. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agh139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk R. J., Edwards D. W., Lewis R. A., Schulenberg J. Smoking and preference for brand of cigarette among adolescents. Journal of Substance Abuse . 1996;8:347–359. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90197-2. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(96)90197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization youth violence and alcohol fact sheet . 2016. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/ft_youth.pdf .

- YouTube 2016. Statistics . Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/yt/press/statistics.html