Abstract

Background

The present study aimed to conduct a systematic review of self-administered shoulder-disability functional assessment questionnaires adapted to Spanish, analyzing the quality of the transcultural adaptation and the clinimetric properties of the new version.

Methods

A search of the main biomedical databases was conducted to locate Spanish shoulder function assessment scales. The authors reviewed the papers and considered whether the process of adaptation of the questionnaire had followed international recommendations, and whether its psychometric properties had been appropriately assessed.

Results

The search identified nine shoulder function assessment scales adapted to Spanish: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH), Upper Limb Functional Index (ULFI), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ), Western Ontario Rotator Cuff index (WORC), Western Ontario Shoulder Instability index (WOSI) and Wheelchair Users Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI). The DASH was adapted on three occasions and the SPADI on two. The transcultural adaptation procedure was generally satisfactory, albeit somewhat less rigorous for the SDQ and WUSPI. Reliability was analyzed in all cases. Validity was not measured for one of the adaptations of the DASH, nor was it measured for the SDQ.

Conclusions

The transcultural adaptation was satisfactory and the psychometric properties analyzed were similar to both the original version and other versions adapted to other languages.

Keywords: cross-cultural adaptation, outcome assessment, questionnaire, shoulder, Spanish version

Introduction

At any given time, shoulder pain may affect up to 18% to 26% of adult individuals,1 with the most usual course being rotator cuff disorders.2 The prevalence of shoulder problems was 17.12% in a primary healthcare setting in Spain.3

More than 40 instruments have been developed for measuring treatment outcomes in shoulder disorders.4–6 Data drawn from physical examinations and/or complementary tests must be completed with assessment of the impact of the disorder from the patient’s point of view (pain, ability to perform certain activities, etc.). The subjective impact of any given disease can vary from one patient to another. Hence, a specific shoulder disorder may affect functional capacity, work performance and/or quality of life differently according to the patient concerned. For example, among older individuals, rotator cuff tears may or may not impact their ability to perform daily functional tasks, whereas, in young people, glenohumeral instability can sometimes be a disease that restricts upper limb activity. Such data, namely patient-reported outcomes, can be obtained by means of self-administered questionnaires. There are over 30 questionnaires,7 none of which has shown itself to be superior to the others.8 Some are applicable to any upper limb disorder and assess it as a whole, regarding it as a single functional unit. There are other questionnaires exclusively designed for the shoulder regions, whether general (for any disease or disorder) or specific (for certain disorders). There are also questionnaires designed for certain subgroups of patients, such as sportspersons and wheelchair users.

It is important to choose questionnaires that are valid, reliable and sensitive to clinical changes. Most have been developed in English-speaking countries for Anglosphere cultures. Hence, if a questionnaire has not been drawn up in the country, geographical region, culture or language in which it is to be applied, an appropriate transcultural adaptation must be made to ensure that it retains the same meaning as the original,9,10 and so prevents erroneous interpretations as a result of cultural or life-style differences. This means, that transcultural adaptation is a more complex process than simple direct or literal translation and, in addition, is no guarantee of the preservation of the psychometric properties in the adapted questionnaire. Accordingly, the psychometric properties of the new version must always be analyzed to ensure that it is a tool equivalent to the original, without any assumptions being made in this respect. In daily practice, healthcare professionals need to assess their results and compare the effectiveness of a given treatment against that reported by other studies. Culturally adapting an existing questionnaire, in preference to developing a new one, is not only more economical, but also may facilitate future comparisons among different populations, provided that conceptual equivalence is successfully achieved. Transcultural adaptation is complex process because it requires changes to both the wording and structure of some questions for the questionnaire to be applied, on an equivalent basis, in populations other than those for which it was created. The use of questionnaires that are not equivalent to the original may give rise to unreliable to confusing results, which could limit the exchange of information among the scientific community.

Spanish is the second most widely spoken language in the world and is witnessing a rise in the number of speakers. In 2015, close on 470 million persons spoke it as their native language.11 Not only is it spoken in Spain and Latin America, with small variations, but also it is habitually used in many other countries. For example, in the USA, over thirty-six million people speak it as their mother tongue. It is thus necessary to have questionnaires adapted to Spanish to ensure that their use is equivalent to that of the original. A systematic review of self-administered shoulder questionnaires adapted to Portuguese was published recently.12 It was found that, although most of the shoulder disability questionnaires had been properly adapted into Brazilian–Portuguese, some of them had either been inadequately tested or had not been tested at all. In 2013,13 questionnaires adapted to Spanish for patients with cervical and lumbar pain were reviewed: no similar reviews of shoulder disorder questionnaires have been published in Spanish.

The present study aimed to conduct a systematic review, by making an exhaustive bibliographic search of self-administered shoulder questionnaires adapted to Spanish, and analyzing both the methodological quality of the transcultural adaptation process and the psychometric properties of the Spanish-language versions.

Methods

Search strategy

We carried out a systematic review of papers that addressed both the transcultural adaptation to Spanish of self-administered questionnaires designed to assess patients with shoulder disabilities, and the process used to validate the resulting Spanish versions. A bibliographic search was made of international electronic databases (MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica dataBASE/EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature/CINAHL and Web of Science) from their date of creation until 31 December 2015. In addition, we searched other databases and directories with bibliographies in Spanish, namely, BIREME (Scielo, Lilacs and IBECS), MEDicina en Español (MEDES), Allied and Complementary Database (AMED), IME and DIALNET. The following search terms and strategy were used in MEDLINE: ‘Outcome’ or ‘Questionnaire’ or ‘Assessment’ or ‘Instruments’ and ‘Shoulder’ or ‘Rotator cuff’ or ‘Upper limb’ and ‘Spanish’ or ‘Spanish version’ or ‘Spanish validation’ or ‘Spanish translation’ or ‘Cross-cultural adaptation’ or ‘Cross-cultural validation’. Similar terms were used to search in other databases. Where necessary, search terms were modified with the assistance of an experienced medical librarian to reflect database vocabularies. In addition, we conducted a manual search using the names of the different shoulder scales as the key word; conducted a search on the Internet, including Google Scholar, to cover other types of publications; and manually examined the references in the papers located.

Selection criteria

Two of the authors reviewed the title and abstract of every paper retrieved. When this suggested that a given paper might be eligible, they then read the full text. We included papers, without language restrictions, reporting observational studies that described the process of transcultural adaptation to Spanish of self-administered questionnaires designed to carry out a functional assessment of patients with shoulder disabilities, and that also analyzed the psychometric properties of the new version. Papers that only analyzed the properties of a previously adapted questionnaire, research protocols and abstracts of conferences were excluded.

Data analysis

Based on the papers selected, two authors structured and analyzed the results of the manuscript. Where any differences of opinion could not be settled, the opinion of a third reviewer was sought. The analysis of the information is described below.

Characteristics of study participants

Data were collected on patients who participated in the study, including country and town, total number of patients included, diagnosis, age, sex, and time taken to complete the questionnaire. Studies were checked to see whether they covered at least 50 patients, which is the ideal minimum number advisable for transcultural adaptation studies.14,15

Assessment of the methodology used to carry out the transcultural adaptation

A check was carried out to ensure that the methodology coincided with the five steps usually recommended in the international bibliography,9,16–20. These steps are: (1) direct translation of the original questionnaire to Spanish (by at least two, independent, bilingual translators whose native language is Spanish); (2) synthesis of translations and resolution of possible disagreements; (3) inverse or back translation (of the consensus Spanish translation into the original language by at least two independent translators who were blinded to the original questionnaire); (4) review by an expert committee to consolidate and develop the pre-final version, ensuring the semantic, idiomatic, experiential and conceptual equivalence of the scale; and (5) pilot testing of the pre-final questionnaire with Spanish-speaking subjects (ideally 30–40), searching for unanswered items and possible problems of comprehension). At each step, we considered whether or not the procedure had been correctly performed (or whether the correction was doubtful), whether it had not been performed, or whether the authors had failed to provide the necessary information.

Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Spanish-language version

The aspects analyzed were: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change.9,15,20–23 Reliability includes internal consistency, test–retest reproducibility, and agreement. Internal consistency is calculated by means of Cronbach’s alpha (α). Where the instrument is made up of subscales, there is the need to calculate the correlation between the items making up each domain and the total scale. Factor analysis is applied to determine the dimensionality of the items. Test–retest reproducibility is calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Agreement is assessed using the standard error of measurement (SEm) and minimal detectable change (MDC90). Validity is measured using correlation coefficients, such as Pearson’s or Spearman’s, and correlation can be direct, indirect or absent. Floor and ceiling effects refer to the percentage of subjects who obtain the lowest and highest possible scores. This should not exceed 15% because, otherwise, the content validity of the scale will be limited because patients with extreme values cannot be distinguished from one another. Sensitivity is the the ability of an instrument to detect important clinical changes across time. The minimum detectable change is mainly measured by reference to effect size (ES) and the standardized response mean (SRM).

Assessment of the direct applicability of scales adapted to one Spanish-speaking country in terms of their possible use in another

We analyzed whether adaptations made in Latin American countries needed some modification to be used in Spain, and vice versa. Despite the fact that the great majority of Spanish words are universal, to ensure comprehension, we assessed whether certain terms needed changing, in cases where they might be seldom used or undergo shifts in nuance or meaning from one culture to another.

Results

The bibliographic search identified eleven relevant papers,24–34 Eight24–31 of these were identified via MEDLINE and the remaining three32–34 were via other sources (two on the Internet and one in the CINAHL database). The manual search failed to locate any relevant papers. These eleven papers yielded nine self-administered questionnaires that had been translated and transculturally adapted to the Spanish population, and in respect of which the clinimetric properties of the new version had been studied. One paper30 published the adaptation of two different questionnaires, thereby giving a total of twelve studies in the eleven papers. In all cases, the original questionnaire had been drawn up in English. There were two questionnaires applicable to any type of upper limb disorder: the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (DASH)24–26 and Upper Limb Functional Index (ULFI).27 There were four general shoulder questionnaires: the Simple Shoulder Test (SST),28 Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI),29.30 Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS)30 and Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ).31 Finally, there were three questionnaires for specific situations: the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index (WORC)32 for patients with rotator cuff disease, the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI)33 for patients with shoulder instability and the Wheelchair Users Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI)34 for patients confined to wheelchairs. The DASH had been adapted and validated on three occasions: two in Spain24,25 and one in Puerto Rico.26 The SPADI had been adapted and validated on two occasions: both in Spain29,30 and practically simultaneously; one of these two adaptations had been carried out jointly with the OSS questionnaire, and both had been published in a single paper.30 In all, there were twelve adaptations for nine questionnaires. Our search located no questionnaire that had been originally developed in Spanish.

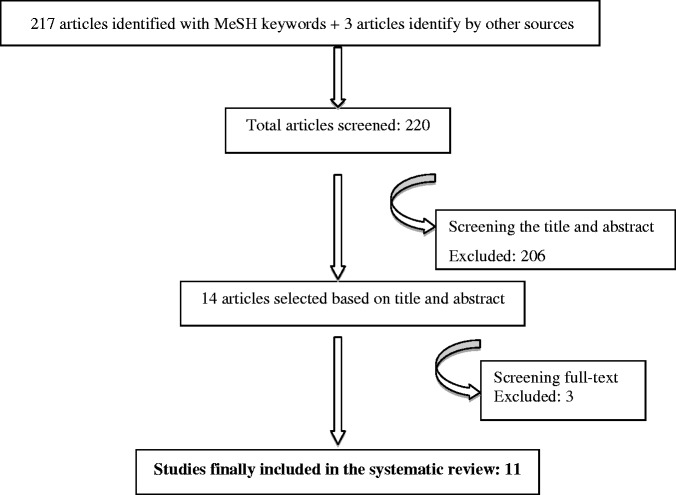

Figure 1.

Flow diagram demonstrating the selection of studies for inclusion. MeSH: Medical Subject Headings.

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the respective populations targeted by the twelve studies. The papers included the adapted scale and instructions for patients in all cases, save for three questionnaires: the adaptation of the DASH in Puerto Rico,26 the OSS30 and the WORC.32 Most of the papers had been published very recently. Six had been published in 201528–30,32,33 and one in 2013.27 Four scales were adapted in Latin American countries26,31–33 and the remainder in Spain.24,25,27–30,34 In eight of the twelve adaptations,25,27–30,32,33 the number of patients exceeded the ideal minimum of 50 recommended for these types of studies. Only one of the three adaptations of the DASH scale, namely the version produced by Hervás et al.,25 included patients with shoulder disabilities; the other two were validated in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome,24 and the version for Puerto Rico was validated in patients after breast cancer surgery.26 The authors who simultaneously adapted the SPADI and OSS questionnaires only included patients intervened for breast cancer;30 in the other adaptation of the SPADI,29 patients with shoulder disorders were included. The adaptation of the WUSPI exclusively included spinal cord injury patients who were wheelchair users.34 The time taken to complete the questionnaire was recorded in only four cases25,30,34 and proved to be similar to that of the original version.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the transcultural-adaptation study populations.

| Scale | Author (year of adaptation) | Country (city or town) | Total number of patients included | Diagnosis | Age (years) | Percentage of women | Completion time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASH24 | Rosales et al. (2002) | Spain (Tenerife) | 42 | Carpal tunnel syndrome | Mean: 54 Range: 34–63 | 85.7% | Not measured |

| DASH25 | Hervás et al. (2006) | Spain (Valencia) | 98 | Different upper limb disorders (73.5% with shoulder problems, essentially: 34.6% subacromial impingement syndrome; 27.3% tendinitis; and 9.1% humerus or scapular (shoulder blade) fractures | Range: 27–76 (over 50%: 25–65) | 64.3 % | 10 |

| DASH26 | Mulero-Portela et al. (2009) | Puerto Rico (San Juan) | 44 | After breast cancer surgery (patients who had undergone operations in the previous 3 years and completed their treatment) | Mean: 52.59 Range: 34–84 | 100% | Not measured |

| ULFI27 | Cuesta-Vargas y Gabel (2013) | Spain (Malaga) | 126 | Different upper limb disorders (56% with shoulder problems, i.e. subacromial impingement syndrome or tendinitis) | Mean: 49 (SD 21) | 54.8 % | Not measured |

| SST28 | Membrilla-Mesa et al. (2015) | Spain (Granada) | 66 | Shoulder pain as a result of different disorders, particularly: 31% humerus fractures; 21.23% calcific tendonitis; and 19.74% rotator cuff tear) | Mean: 51 (SD 12) | 59.13 % | Not measured |

| SPADI29 | Membrilla-Mesa et al. (2015) | Spain (Malaga) | 136 | Shoulder pain as a result of different disorders, particularly: 22.1% bicipital tendinitis, 21.3% humerus fractures, 17.6% rotator cuff tear and 11.8% calcific tendonitis) | Mean: 49.8 (SD 15) | 55.1% | Not measured |

| SPADI30 | Torres-Lacomba et al. (2015) | Spain (Alcalá de Henares) | 120 | After breast cancer surgery (patients with clinical course of less than 6 months) | Mean: 54.2 (SD 11) | 100 % | 3 (SD 1.9) |

| OSS30 | Torres-Lacomba et al. (2015) | Spain (Alcalá de Henares) | 120 | After breast cancer surgery (patients with clinical course of less than 6 months) | Mean: 54.2 (SD 11) | 100 % | 3.4 (SD 1.4) |

| SDQ31 | Álvarez-Nemegyei et al. (2005) | Mexico (Yucatán) | 35 | Shoulder pain as a result of subacromial impingement syndrome | Mean: 55 (SD 9) | 77.1% | Not measured |

| WORC32 | Arcuri et al. (2015) | Argentina (Buenos Aires) | 60 | Tendinitis or rotator cuff tear | Mean: 57 (SD 12.3) Range: 19–76 | 44 % | Not measured |

| WOSI33 | Arcuri et al. (2015) | Argentina (Buenos Aires) | 60 | Shoulder instability | Mean: 40.12 (SD 17) Range: 17–65 | 45% | Not measured |

| WUSPI34 | Arroyo-Aljaro y González-Viejo (2009) | Spain (Barcelona) | 42 | Spinal cord injuries (28.9% cervical, 36.8% upper dorsal and 34.2% lower dorsal) | Median: 40 Range: 15–69 | 19 % | 5 |

DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire; ULFI, Upper Limb Functional Index; SST, Simple Shoulder Test; SPADI, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; SDQ, Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; WORC, Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; WOSI, Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index; WUSPI, Wheelchair Users Shoulder Pain Index.

The DASH has two additional optional modules, each comprising four items, which were adapted in the version by Hervás et al.25 and in that produced in 2009 for Puerto Rican patients.26 Each of the original questionnaires specified the period of time preceding the questionnaire completion date that patients were to take into account when answering. However, in the adaptation of the WUSPI34 and in one of the adaptations of the SPADI,30 the adapted scale failed to give any clear indication of the period of time that patients were expected to analyze when assessing their shoulder status. In general, the transcultural adaptation process of all scales required modifications, albeit of little importance, with respect to the original version. In the three adaptations of the DASH,24–26 no identical questionnaires were obtained. In the version for Puerto Rico,26 some Anglicisms had to be included in view of the fact that the country’s second language is English. Similarly, the two adaptations of the SPADI29,30 were not identical. Even so, the different variants in the two questionnaires were equivalent.

The main results of the evaluation of the methodology used for transcultural adaptation are analyzed in Table 2 (adapted from Puga et al.11). The three versions of the DASH,24–26 the two adaptations of the SPADI,29,30 and the OSS,30 WORC32 and WOSI33 versions rigorously complied with the international recommendations. The SDQ31 and WUSPI34 were the least strict in this respect. Although pilot testing was performed for eight scales,24–26,29,30,32,33 only three24,26,29 included more than 30 subjects. The questionnaires were well accepted by patients, who reported no difficulties in understanding items or completing them.

Table 2.

Assessment of the methodology used for transcultural adaptation of questionnaires.

| Scale | Translation | Summary | Back translation | Analysis by expert committee | Pilot test (number of patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASH24 Rosales et al. (2002) | + | + | + | + | + (50) |

| DASH25 Hervás et al. (2006) | + | + | + | + | + (15) |

| DASH26 Mulero-Portela et al. (2009) | + | + | + | + | + (32) |

| ULFI27 | + | + | + | ? | – |

| SST28 | + | + | + | ? | – |

| SPADI29 Membrilla-Mesa et al. (2015) | + | + | + | + | + (40) |

| SPADI30 Torres-Lacomba et al. (2015) | + | + | + | + | + (20) |

| OSS30 | + | + | + | + | + (20) |

| SDQ31 | − | 0 | − | 0 | – |

| WORC32 | + | + | + | + | + (10) |

| WOSI33 | + | + | + | + | + (10) |

| WUSPI34 | ? | 0 | ? | 0 | – |

DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire; ULFI, Upper Limb Functional Index; SST, Simple Shoulder Test; SPADI, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; SDQ, Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; WORC, Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; WOSI, Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index; WUSPI, Wheelchair Users Shoulder Pain Index; (+), Correctly done; (?), Doubtful; (–), Incorrectly done or not done; (0), No information given as to whether or not done.

The main psychometric properties analyzed in the Spanish versions are listed in Table 3. No study assessed all the metric properties of the new version. In general, the conclusion of the authors of each of the adaptations was that the psychometric properties assessed were acceptable and comparable to those of the original versions.

Table 3.

Principal psychometric properties analyzed in the adapted questionnaires.

| Scale | Total internal consistency (Cronbach's α) | Test–retest reproducibility: number of participants (time between two evaluations) ICC | Instrument of comparison: validity (correlation coefficient) (negative values indicate inverse correlation) | Floor/ceiling effects | Sensitivity ES SRM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASH24 Rosales et al. (2002) | 0.95 | 42 (7 days) 0.97 (95% CI = –1.98 to 0.52) | Not used (not calculated) | – | – |

| DASH25 Hervás et al. (2006) | 0.96 | 30 (7 days to 10 days) 0.96, p < 0.01 | SF-36: physical functioning subscale: –0.509 and pain subscale: –0.693. Significant correlation (p < 0.01) with all SF-36 dimensions in the direction expected under the initial hypothesis | – | 1.03 0.86 |

| DASH26 Mulero-Portela et al. (2009) | 0.97 (item range: 0.44 to 0.85) | Not analyzed | FACT-B: (range 0.096 to 0.682). Significant correlation (p < 0.01) with four of the five FACT-B subscales | No/No | – |

| ULFI27 | 0.94 (item range: 0.92 to 0.96) | 35 (7 days) 0.93 (range 0.92 to 0.95) | EQ-5D-3L: –0.59 (for the pain subscale: –0.51) QuickDASH: not valid (more than 30% of questionnaires with excessive missing answers) Factor structure analysis: unidimensional | – | – |

| SST28 | 0.793 (item range: 0.667 to 0.723) | 21 (2 days) 0.912 (range 0.687 to 0.944) | DASH: –0.73 VAS pain: –0.53 SF-12: physical functioning subscale –0.47 and mental subscale –0.43, con p < 0.001 Factor structure analysis: tridimensional | No/No | – |

| SPADI29 Membrilla-Mesa et al. (2015) | 0.92 (95% CI = 0.91 to 0.95) and 0.82 (95% CI = 0.76 to 0.86) for each of the two factors | 56 (2 days) 0.91 (95% CI = 0.88 to 0.94) with item range of 0.89 to 0.93 | Significant correlations (p < 0.01) in the direction expected under the initial hypothesis DASH: pain subscale 0.80 and disability subscale 0.76 SF-12: total 0.40 (with the physical functioning and mental subscales) SST: pain subscale -0.71 and disability subscale –0.75 VAS pain: pain subscale 0.67 and disability subscale 0.65 Factor structure analysis: bidimensional | – | – |

| SPADI30 Torres-Lacomba et al. (2015) | 0.965 (0.931 on the pain subscale and 0.953 on the function subscale) | 20 (2 days) 0.992 (0.986 in the pain subscale and 0.991 on the function subscale) with p < 0.01 | OSS: –0.674 FACT-B: –0.298 SDQ: 0.432 SF-36: –0.452 to –0.315 (for the physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain and role-emotional dimensions) with p < 0.01 | No/No | Global scale 0.59 0.82 Pain subscale 0.59 0.78 Function subscale 0.82 1.13 p < 0.0001 |

| OSS30 | 0.947 | 20 (2 days) 0.974 | SPADI: –0.674 (pain subscale –0.640 and disability subscale –0.645) FACT-B: –0.343 SDQ: –0.469 SF-36: 0.312 to 0.391 (for the physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain and role-emotional dimensions) with p < 0.01 | No/No | –0.50 –0.70 p < 0.0001 |

| SDQ31 | 0.99 | 35 (1 hour) 0.99 (95% CI = 0.998 to 0.999) | Not used (not calculated) | – | |

| WORC32 | 0.952 (range among the 5 domains: 0.824 to 0.953) | 10 (14 days to 21 days, median 14) 0.909 (95% CI = 0.841 to 0.949) | SST: 0.756 Constant Scale: 0.60 | No/No | |

| WOSI33 | 0.948 (range among the 4 domains: 0.783 to 0.906) | 60 (14 days to 21 days, median 14) 0.851 (95% CI = 0.587 to 0.879) | SST: 0.498 Constant Scale: 0.60 | No/No | |

| WUSPI34 | 0.88 | 8 (not specified) 0.96 | VAS pain (in 8 of 45 patients): 0.90 | Yes/No |

DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire; ULFI, Upper Limb Functional Index; SST, Simple Shoulder Test; SPADI, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; SDQ, Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; WORC, Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; WOSI, Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index; WUSPI, Wheelchair Users Shoulder Pain Index; ICC, Intraclass correlation coefficient; CI, confidence interval; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey; FACT-B, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast; EQ-5D-3L, European Health Questionnaire 5 Dimensions 3 Levels; VAS, Visual analog scale; SF-12, Short Form 12 Health Survey; ES, effect size; SRM, standardized response mean.

In terms of reliability, internal consistency was assessed in all scales, test–retest reproducibility in all but one26 and agreement in only five.27–29,32,33 When the test–retest was performed, there were only six scales,24,25,27,29,31,33 which exceeded the ideal number of patients recommended for this assessment (i.e. 29). Total internal scale consistency was excellent for seven questionnaires,24–27,30–33 good for the WUSPI34 and acceptable for the SST.28 In the case of the adaptation of the SPADI by Membrilla-Mesa et al.,29 it was good for one of the factors and excellent for the other. The test–retest time used was too long for the WORC32 and WOSI questionnaires33 (up to 21 days), and too short for the SDQ31 (1 hour). The ICC was very good in all cases. Agreement was analyzed in five questionnaires.27–29,32,33 In the adaptation to Spanish of the SPADI, Membrilla-Mesa et al.29 only analyzed the MDC95 value, which was 12.2%. In the other four questionnaires, both the SEm and MDC90values were analyzed, with the respective results for the two being: ULFI, 3.52% and 8.03% (equivalent to 2 points of the maximum scale score of 25);27 SST, 2.21% and 6.2%;28 WORC 192.76 (domain range 39.43–63.82) and 533 (domain range 109.21–176.78) for a total scale score range of 0–2100;33 and WOSI, 192.76 (domain range 109.21–176.78) and 533 (domain range 109.21–176.78) for a total scale score range of 0–2100.33

Validity was assessed in all questionnaires, with the exception of the adaptations of the DASH in Puerto Rico26 and the SDQ in Mexico.31 Validity varied according to the comparison instruments used but was generally adequate. The comparators used to validate the WORC and WOSI in Argentina32,33 were the Constant Scale and a version of the SST adapted to the Argentine population, for which there are no data published in the form of a paper.35 Construct validity was only properly assessed in the adaptations of the DASH by Hervás et al.25 and the SPADI by Membrilla-Mesa et al.,29 in that there was a prior hypothesis regarding the correlation of the instruments being compared. Factor structure analysis was performed for only three questionnaires, the ULFI,27 the SST28 and one of the two adaptations of the SPADI,29 with all being adapted by the same work group and the scales proving unidimensional in the first case, tridimensional in the second case and bidimensional in the third case. Only in two cases27,29 was the number of patients used appropriate (> 100). Floor and ceiling effects were not analyzed in five questionnaires,24,25,28,29,31 and, in the remainder, the WUSPI alone displayed evidence of a floor effect.34

Sensitivity was examined in only three scales.25,30 ES and SRM values were obtained for the DASH adapted by Hervás et al.,25 indicating high sensitivity in both cases. For one of the adaptations of the SPADI,30 these values were moderate–high, respectively, for the global scale, and high in both cases for the functional subscale. The ES and SRM values for the OSS questionnaire30 were low.

The clinimetric properties of the two optional DASH modules could not be analyzed in the adaptation of Hervás et al.,25 as a result of the low number of respondents, and were similarly not analyzed in the veraion by Mulero-Portela et al.26 for Puerto Rican patients.

In four questionnaires,26,31–33 the transcultural adaptations were produced in Latin American countries. In three of these cases,31–33 none of the cultural flaws were so marked as to prevent the questionnaire being used in Spain. The introduction of small changes in some of the vocabulary would permit the instruments to be used without problem in Spain: for example, in the adaptation of the SDQ for Mexico31 ‘auto’ could be replaced by ‘coche’ and ‘manubrio’ by ‘manillar’. Similarly, in the case of the adaptations produced in Spain, which might contain words that were inappropriate for subjects of Latin American origin, these could be modified (e.g. by replacing ‘coger’ with ‘agarrar’) and, equally, be applicable there. In the case of the adaptation of the DASH to the Puerto Rican population,26 it was necessary to permit some Anglicisms, which would render it inapplicable to Spain. In Spain, either of the other two versions of the DASH could be used.24,25

Discussion

Outcome measures developed from the patient’s standpoint are important for assessing the effectiveness of treatments administered. Indeed, clinician-made measurements correlate poorly with disability as perceived by patients, which, moreover, is the aspect of most relevance to them.36 At an international level, numerous questionnaires have been developed for assessing patients’ self-perceived impact of their shoulder disorders. There are more than 30 such questionnaires, and they are being increasingly used: each has advantages and disadvantages with respect to the rest, and none is superior to any other. Interest in this issue is growing and a number of reviews have been published in recent years.6–8,22,37–47 Most of the questionnaires have been developed in English-speaking countries. Spanish is the second most widely spoken language in the world, with widespread geographical coverage,11 encompassing countries that use it as an official language, as well as cases where it is spoken by immigrants who reside in countries having other mother tongues. Adapting an already existing scale and ensuring that the new version maintains the psychometric properties of the original, is preferable to creating a wholly new scale. The latter option entails a greater effort in terms of cost and time, and increases the diversity of questionnaires. A single scale facilitates comparisons across different populations. Transcultural adaptation must ensure conceptual equivalence with the original version.

The goal of the present study was to conduct a systematic review of self-administered shoulder questionnaires adapted to Spanish, analyzing both the methodological quality of the transcultural adaptation process and the psychometric properties of the new version obtained. We located eleven papers24–34 on nine questionnaires, six of which had been published in 2015.28–30,32,33 Two were applicable to the entire upper limb: the DASH (adapted on three occasions)24–26 and the ULFI.27 Four were general shoulder questionnaires: the SST,28 SPADI (adapted on two occasions),29,30 OSS30 and SDQ.31 Lastly, there were three questionnaires for specific situations: the WORC32 for patients with rotator cuff disease, the WOSI33 for cases of instability and the WUSPI34 for wheelchair users. Of these, the most widely used at an international level are the DASH, SST, SPADI and OSS.

In the adaptation of three questionnaires only women (intervened for breast cancer) were included in two,26,30 and patients with carpal tunnel syndrome in another.24 This had no relevant influence on the quality of the transcultural adaptation or on the psychometric properties of the questionnaires adapted. Similarly, the fact that four studies24,26,31,34 had fewer than 50 participants, a number lower than the ideally recommended minimum for transcultural adaptation studies, had no special significance.17

There is still no clear international consensus on the optimal approach to carrying out transcultural adaptation:10 indeed, there are over 30 methods and no ‘gold standard’. What does appear to be agreed is that inverse (or back) translation and pilot testing are essential.10 The internationally recognized criteria for the process of adaptation to Spanish were followed with maximum rigor in the three versions of the DASH,24–26 the two adaptations of the SPADI,29,30 and the OSS30 and WOSI31 questionnaires. By contrast, there were important shortcomings in the adaptations of the SDQ31 and WUSPI.34 In general, there were no unduly pronounced cultural flaws, except in the case of the Puerto Rican population in the adaptation of the DASH,26 where some Anglicisms had to be allowed. In the other three questionnaires adapted in Latin American countries,31–33 the introduction of small changes in certain words used would make it possible for these to be used without any problem of comprehension in Spain. Conversely, the same could be carried out with questionnaires adapted in Spain.

When it comes to choosing which questionnaire to use in a specific situation, consideration must be given to methodological criteria (psychometric properties) and practices (time needed for completion and scoring; usefulness for specific disorders). No study assessed all the possible psychometric properties. Reliability was analyzed in a number of ways in all the questionnaires, and validity in all but one of the adaptations of the DASH24 and SDQ.31 In the case of reliability, internal consistency was assessed in all scales, test–retest reproducibility in all but one26 and agreement in only five.27–29,32,33 The psychometric properties analyzed were acceptable and generally similar to those of the original version and other scale versions adapted to other languages.

The DASH is the most widespread and best rated questionnaire, along with its simplified 11-item version (Quick DASH),7 not adapted to Spanish.48 It is the single most transculturally adapted questionnaire.37 The psychometric properties of the version by Hervás et al.,25 produced in Spain, have been studied in depth, although its agreement values have not been analyzed. It is a long questionnaire, which, instead of being specific to the shoulder, addresses the entire upper limb, and would thus be generally preferable for use in research. In this respect, another option would be to use the ULFI, for which transcultural adaptation has been less rigorous:27 in the case of this scale, unlike the DASH, data are available on agreement but not on sensitivity. Only one of the three adaptations of the DASH, the version by Hervas et al.,25 was carried out on patients with shoulder disabilities.

The psychometric properties of the SPADI and OSS have similarly been fully and rigorously analyzed, with the single exception of their agreement values. Both are very short. The OSS questionnaire is the most widely used in the UK,49 and, at an international level, is the most widely adapted and validated general shoulder scale. Even so, it is relatively little used in scientific literature and is not suitable for patients with instability. Aside from being the most sensitive questionnaire, the SPADI is also the instrument that is most widely accepted by the scientific community:50 it would be the first choice for both clinical practice and research,7,8 and would probably also be best for primary care.51

The SST and SDQ questionnaires are likewise short and applicable to any shoulder disability. The former is widely used in the USA7 but, because it only assesses functionality, should be associated with a pain scale. Furthermore, binary replies allow for few nuances or shades of difference. The latter instrument appears to have a notable ceiling effect, an aspect not analyzed in the Spanish version, in which validity was also not examined.

The WORC, WOSI and WUSPI questionnaires are specific for rotator cuff disease, shoulder instability and wheelchair users, respectively. The first two have been adapted to the Argentine population:32,33 both are somewhat long when it comes to their being applied. In the third,34 the quality of the transcultural adaptation and validity assessment was poor, although reliability was good.

Based on the results of our review, within the questionnaires adapted to Spanish, we consider the SPADI to be the first choice for both clinical practice and research on shoulder pain, and the DASH to be generally preferable for use in research to address the entire upper limb, given that it is not specific to the shoulder. Among patients with rotator cuff disease, the SPADI would be preferable to the WORC because the adaptation of the latter is of worse quality. For other specific situations, such as shoulder instability and wheelchair users, there are the WOSI and WUSPI questionnaires, respectively. These adaptations are of inferior quality to that of the SPADI questionnaire.

In the searches conducted, every effort was made to identify and retrieve all relevant questionnaires that had been adapted into Spanish. It has to be said, however, that even though the most commonly used databases (including local databases) were selected, some studies may not have been detected because some journals may not be indexed in these databases. Accordingly, this could be viewed as a limitation of our review. As strong points of our review, it should be stressed that both the rigor of the questionnaire-adaptation process and the psychometric properties studied were analyzed by two authors. Furthermore, the search process was so exhaustive as to render it extremely unlikely that any other published scales adapted to Spanish might have gone undetected.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The paper has not been presented at any society or meeting.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Linaker CH, Walker-Bone K. Shoulder disorders and occupation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheum 2015; 29: 405–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr KP. Rotator cuff disease. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2004; 15: 475–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frau-Escales P, Langa-Revert Y, Querol-Fuentes F, Mora-Amérigo E, Such-Sanz A. Shoulder musculoskeletal disorders in primary care. A cross-sectional study in a health care center of the Valencia Health Care Agency. Fisioterapia 2013; 35: 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvie P, Pollard TC, Chennagiri RJ, Carr AJ. The use of outcome scores in surgery of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg 2005; 87: 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roe Y, Soberg HL, Bautz-Holter E, Ostensjo S. A systematic review of measures of shoulder pain and functioning using the International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 28: 73–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wylie JD, Beckmann JT, Granger E, Tashjian RZ. Functional outcomes assessment in shoulder surgery. World J Orthop 2014; 5: 623–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angst F, Schwyzer HK, Aeschlimann A, Simmen BR, Goldhahn J. Measures of adult shoulder function: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) and its short version (QuickDASH), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Society standardized shoulder assessment form, Constant (Murley) Score (CS), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ), and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63(Suppl 11): S174–S188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt S, Ferrer M, González M, et al. Evaluation of shoulder-specific patient-reported outcome measures: a systematic and standardized comparison of available evidence. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muñiz J, Elosua P, Hambleton RK. Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los tests: segunda edición. Psicothema 2013; 25: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein J, Santo RM, Guillemin F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68: 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Instituto Cervantes. Informe: El español una lengua viva, 2015. http://www.cervantes.es/imagenes/File/prensa/El%20espaol%20una%20lengua%20viva.pdf (accessed 6 February 2016).

- 12.Puga VO, Lopes AD, Costa LO. Assessment of cross-cultural adaptations and measurement properties of self-report outcome measures relevant to shoulder disability in Portuguese: a systematic review. Rev Bras Fisioter 2012; 16: 85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy DR, López M. Neck and back pain specific outcome assessment questionnaires in the Spanish language: a systematic literature review. Spine J 2013; 13: 1667–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1999.

- 15.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46: 1417–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000; 25: 3186–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health 2005; 8: 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramada-Rodilla JM, Serra-Pujadas C, Delclos-Clanchet GL. Adaptación cultural y validación de cuestionarios de salud: revisión y recomendaciones metodológicas. Salud Publica Mex 2013; 55: 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lujan-Tangarife JA, Cardona Arias JA. Construcción y validación de escalas de medición en salud: revisión de propiedades psicométricas. Arch Med 2015; 11: 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munro B. Statistical methods for health care research, Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michener LA, Leggin BG. A review of self-report scales for the assessment of functional limitation and disability of the shoulder. J Hand Ther 2001; 14: 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL, Ostelo RWJG, Bouter LM, de Vet HCW. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: a scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual Life Res 2012; 21: 651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosales RS, Delgado EB, Díez de la Lastra-Bosch I. Evaluation of the Spanish version of the DASH and carpal tunnel syndrome health-related quality-of-life instruments: cross-cultural adaptation process and reliability. J Hand Surg Am 2002; 27: 334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hervás MT, Navarro Collado MJ, et al. Spanish version of the DASH questionnaire. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, validity and responsiveness. Med Clin (Barc) 2006; 127: 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulero-Portela AL, Colón-Santaella CL, Cruz-Gómez C. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire: Spanish for Puerto Rico version. Int J Rehabil Res 2009; 32: 287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuesta-Vargas AI, Gabel PC. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity of the Spanish version of the Upper Limb Functional Index. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11: 126–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Membrilla-Mesa MD, Tejero-Fernández V, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Arroyo-Morales M. Validation and reliability of a Spanish version of Simple Shoulder Test (SST-Sp). Qual Life Res 2015; 24: 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Membrilla-Mesa MD, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Pozuelo-Calvo R, Tejero-Fernández V, Martín-Martín L, Arroyo-Morales M. Shoulder Pain and Disability Index: cross cultural validation and evaluation of psychometric properties of the Spanish version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015; 13: 200–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres-Lacomba M, Sánchez-Sánchez B, Prieto-Gómez V, et al. Spanish cultural adaptation and validation of the shoulder pain and disability index, and the Oxford shoulder score after breast cancer surgery. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015; 13: 63–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Puerto-Ceballos I, Guzmán-Hau W, Bassol-Perea A, Nuño-Gutiérrez BL. Development of a Spanish-language version of the Shoulder Disability Questionnaire. J Clin Rheumatol 2005; 11: 185–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arcuri F, Barclay F, Nacul I. Traducción, adaptación transcultural, validación y medición de propiedades de la versión en español del índice Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC). Artroscopia 2015; 22: 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arcuri F, Nacul I, Barclay F. Traducción, adaptación transcultural, validación y medición de propiedades de la versión en español del índice Western Ontario Shoulder Instability (WOSI). Artroscopia 2015; 22: 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arroyo Aljano R, González-Viejo MA. Validación al castellano del Wheelchair Users Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI). Rehabilitación 2009; 43: 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arcuri F, Barclay F, Nacul I. Translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the Simple Shoulder Test to Spanish. Orthop J Sports Med 2014; 2(4 Suppl): 2325967114S00233–2325967114S00233. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roddey TS, Cook KF, O’Malley KJ, Gartsman GM. The relationship among strength and mobility measures and self-report outcome scores in persons after rotator cuff repair surgery: impairment measures are not enough. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14(1 Suppl S): 95–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St-Pierre C, Desmeules F, Dionne CE, Frémont P, MacDermid JC, Roy JS. Psychometric properties of self-reported questionnaires for the evaluation of symptoms and functional limitations in individuals with rotator cuff disorders: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2016; 38: 103–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang H, Grant JA, Miller BS, Mirza FM, Gagnier JJ. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome instruments for use in patients with rotator cuff disease. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43: 2572–2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roller AS, Mounts RA, DeLong JM, Hanypsiak BT. Outcome instruments for the shoulder. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badalamente M, Coffelt L, Elfar J, et al. Measurement scales in clinical research of the upper extremity, part 2: outcome measures in studies of the hand/wrist and shoulder/elbow. J Hand Surg Am 2013; 38: 407–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roy JS, Esculier JF. Psychometric evidence for clinical outcome measures assessing shoulder disorders. Phys Ther Rev 2011; 16: 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Longo UG, Vasta S, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Scoring systems for the functional assessment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. Sports Med Arthrosc 2011; 19: 310–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright RW, Baumgarten KM. Shoulder outcomes measures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2010; 18: 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Placzek JD, Lukens SC, Badalanmenti S, et al. Shoulder outcome measures: a comparison of 6 functional tests. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32: 1270–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bot SD, Terwee CB, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM, Dekker J, de Vet HC. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 335–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kirkley A, Griffin S, Dainty K. Scoring systems for the functional assessment of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 2003; 19: 1109–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kennedy CA, Beaton DE, Smith P, et al. Measurement properties of the QuickDASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) outcome measure and cross-cultural adaptations of the QuickDASH: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 2013; 22: 2509–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varghese M, Lamb J, Rambani R, Venkateswaran B. The use of shoulder scoring systems and outcome measures in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2014; 96: 590–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Green SE, et al. Core domain and outcome measurement sets for shoulder pain trials are needed: systematic review of physical therapy trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68: 1270–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paul A, Lewis M, Shadforth MF, Croft PR, Van der Windt DA, Hay EM. A comparison of four shoulder-specific questionnaires in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 1293–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]