Abstract

Objective:

Stem cell-based therapies are promising in regenerative medicine for protecting and repairing damaged brain tissues after injury or in the context of chronic diseases. Hypoxia can induce physiological and pathological responses. A hypoxic insult might act as a double-edged sword, it induces cell death and brain damage, but on the other hand, sublethal hypoxia can trigger an adaptation response called hypoxic preconditioning or hypoxic tolerance that is of immense importance for the survival of cells and tissues.

Data Sources:

This review was based on articles published in PubMed databases up to August 16, 2017, with the following keywords: “stem cells,” “hypoxic preconditioning,” “ischemic preconditioning,” and “cell transplantation.”

Study Selection:

Original articles and critical reviews on the topics were selected.

Results:

Hypoxic preconditioning has been investigated as a primary endogenous protective mechanism and possible treatment against ischemic injuries. Many cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the protective effects of hypoxic preconditioning have been identified.

Conclusions:

In cell transplantation therapy, hypoxic pretreatment of stem cells and neural progenitors markedly increases the survival and regenerative capabilities of these cells in the host environment, leading to enhanced therapeutic effects in various disease models. Regenerative treatments can mobilize endogenous stem cells for neurogenesis and angiogenesis in the adult brain. Furthermore, transplantation of stem cells/neural progenitors achieves therapeutic benefits via cell replacement and/or increased trophic support. Combinatorial approaches of cell-based therapy with additional strategies such as neuroprotective protocols, anti-inflammatory treatment, and rehabilitation therapy can significantly improve therapeutic benefits. In this review, we will discuss the recent progress regarding cell types and applications in regenerative medicine as well as future applications.

Keywords: Angiogenesis Factor, Cell Transplantation, Endogenous Stem Cells, Genome Editing, Hypoxia, Hypoxic Preconditioning, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells, Neurological Disorders, Tumor

INTRODUCTION

Pluripotent stem cells, regardless of their cell source, are capable of self-renewal and give rise to multiple specialized cell types, even to a complete adult organism.[1] This has allowed rapid progress in stem cell biology. However, transplanted cells seem to be rejected by the host and don’t to survive long enough for functional integration to might occur. The creation of adult-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) allows autologous applications for disease treatments to become one of the most exciting areas in stem cell therapy.[2] To evaluate the approaches that might have provided promising options for regenerative medicine, especially for the treatment of the heterogeneous plethora of neurological disorders, we summarized the recent experimental results and further discussed the potential improvement of transplanted cell survival after hypoxic preconditioning.

ISCHEMIC CONDITIONS IN BRAIN DISORDERS

Hypoxia or lower oxygen levels might occur in daily life, in different parts of the body, and under a variety of conditions (For example, individuals in mountainous regions can adapt to hypoxia generated by lower oxygen levels at higher elevations, which allow managing to maintain normal physiological functions in plateau residents). In the nervous system, ischemic/hypoxic conditions are more likely to happen after brain disorders as neuronal activities consume a large amount of oxygen and glucose for maintenance of normal brain activities. Embryos and newborns have a significantly higher ability to survive hypoxic and ischemic conditions. It is well known that bone marrow cells survive well in the physiologically hypoxic conditions (1–6% O2) in the bone marrow. In addition, blood oxygen and glucose levels in the brain, or an ischemic event caused by occlusion of blood vessels, could greatly influence cell survival and brain functions.[3,4] Although decreased energy demands prevail under hypoxic and ischemic conditions as a compensatory response, severe ischemia leads to neuronal cell death and injuries to other systems, such as disruption of the blood-brain barrier due to damage to endothelial cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM). On the other hand, manipulation of hypoxic conditions within the sublethal range in physiological and pathological conditions shows a priming effect of improving the tolerance of cells, tissues, and the whole body to future insults. Translation of hypoxic preconditioning into clinical applications has been an active research area. We summarize the adaptive changes focusing on cellular signaling pathways and gene regulation following hypoxia and hypoxic preconditioning as well as the potential clinical application of preconditioning in cell-based therapies.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL ETIOLOGY OF BRAIN DISORDERS

Neurological disorders are associated with degeneration of neurons and gradual losses of neural functions. Due to the phenotypic heterogeneity, complicated neuronal connectivity, and the multitude of interactions among neurons, astrocytes, microglial cells, oligodendrocytes, and stem/progenitor cells, neurological disorders are often regarded as some of the most complicated disease conditions to decipher and treat.[5,6,7] Recent research has identified multiple factors and key mechanisms that regulate distinct cell plasticity, such as cell type-specific differentiation and culture protocols. These specific manipulations of cells (e.g., stem cell-derived/differentiated neurons in vitro) highlight the potential for the treatment of central nervous system (CNS) disorders such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson's disease (PD), and Alzheimer's disease (AD).[8] However, there is still a great unmet translational need for improving the disease models and effective translation of therapeutic interventions. So far, much effort has been done to increase the feasibility and efficacy of cell-based therapies. In this review, we highlight the major types of endogenous and exogenous stem cells and discuss the recent progress in cell-based therapy for CNS disorders.

Neural stem cells (NSCs) and neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the adult brain are mainly located in two regenerative niches: the subventricular zone (SVZ) flanking the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus (DG) in the hippocampus.[9,10,11,12,13,14] In rodent models, neurons originating from these two areas have distinct destinies: the neuroblasts derived from the SVZ migrate along the rostral migratory stream, become interneurons, and integrate with other cells in the olfactory bulb. The newborn neurons of the SGZ differentiate and assimilate into the local neural network of the hippocampus where they are involved in learning, memory, and mood regulation.[14] Interestingly, human SVZ neurogenesis exhibits an evolutionary divergence which shows a remarkable difference from other vertebrates. In humans, it was shown that long-distance migration of SVZ-derived NPCs to the olfactory bulbs is virtually nonexistent, while there is abundant neurogenesis from the SVZ into the adjacent striatum.[15,16]

Neurogenic activities in the SVZ and SGZ may be upregulated following stroke.[17,18] Endogenous NPCs proliferate after ischemia and differentiate into neuroblasts and astrocytes, which subsequently migrate along the route from the SVZ to the infarct region.[19,20,21] Increasing evidence suggests that some factors, such as lipid accumulation, suppress the homeostatic and regenerative functions of NSCs (e.g., perturbation of the microenvironmental fatty acid metabolism in AD impedes neural regeneration[22]). Accumulating evidence unveils that NPC functions are regulated by different signals, which should be taken into consideration when optimizing cell-based therapies.[23,24,25,26,27] Identification and modification of inhibitory factors might help to augment the brain's adaptive endogenous regeneration to various neurological disorders and improve stem cell-mediated brain repair.

HYPOXIA AND DISEASES

Hypoxia and mobilization of endogenous stem cells

The activation of chemokine receptors can increase the number of migrating NPCs (e.g., the CXC chemokine receptor type 4 [CXCR4], which is the cognate receptor for stromal-derived factor 1 [SDF-1], crucial for coupling neurogenesis with angiogenesis after stroke and directing the migration of neuroblasts to the infarct region[28]). In addition, C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2), the cognate receptor for monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, is upregulated in migrating neuroblasts following ischemia and is critical for proper destination targeting.[29]

Neurotrophic and growth factors also play important roles in the regulation of adult regeneration, including, but not limited to, granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), insulin growth factor (IGF-1), glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).[30,31,32] G-CSF and IGF-1 can reduce NPC death through altering key survival pathways (e.g., the phosphoinositide 3 kinase-Akt pathway). Several recent clinical trials demonstrated the ability of G-CSF to both mobilize endogenous bone marrow cells and exert its neuroprotective effects to promote stroke recovery.[33] BDNF and noggin, another developmental protein, can actively recruit NPCs to form new medium spiny projection neurons (MSNs) and ameliorate the progressive impairment of motor function and cognition associated with Huntington's disease (HD).[34] In addition to growth factors, anti-inflammatory drugs such as indomethacin, noncoding RNA, and hormones can also increase endogenous NPC proliferation.[35,36] Together, these studies corroborate the principle that factors that promote neurogenesis might contribute to better cell-based therapies for neurological disorders.

Mobilization of stem cells from the bone marrow also has great therapeutic potential.[37] Plerixafor (also known as age-related macular degeneration (AMD)-3100, an inhibitor of CXCR4) significantly increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2 (VEGFR-2)-positive cells in the peripheral blood, elevated SDF-1 levels, and promoted blood vessel formation in an ischemic flap model. Hypoxia-induced upregulation of CXCR4 has been studied in CD34+ cells and cardiac progenitor cells in vitro and after transplantation (including in utero or intravenously), which resulted in facilitated recruitment of donor CD34+ cells to the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury.[38] Co-culture of neurons with SDF-1-secreting olfactory ensheathing cells after oxygen–glucose deprivation (OGD) treatment showed enhanced neurite outgrowth.[39] G-CSF could mobilize CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells and effective to reduce the microglial responses in the preterm brain following hypoxic-ischemic injury.[40] Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), erythropoietin (EPO), G-CSF, and interleukin-10 (IL-10) showed synergistic effects for increasing the homing and differentiation of NSCs and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) into the peri-infarct/lesion regions.[41,42,43,44] Fasudil, an inhibitor of Rho kinase, significantly increases cellular G-CSF levels, contributing to NSC mobilization to treat hypoxia/reperfusion injury. Mobilization of intravenously injected endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) can be induced by shock wave treatment from the peripheral blood to ischemic hind limbs.[45] In chronic hypoxia secondary to pulmonary hypertension, when migratory adaption to SDF-1 and cell adhesion are significantly inhibited, hypoxic EPCs with upregulated VEGFR-2+/SCA-1+/CXCR-4+ (SCA-1: stem cell antigen 1) seem insufficient to stimulate the remodeling of the vascular network.[46] Enhancement of EPO/EPOR is demonstrated to attenuate hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension, while EPOR (-/-) mice fail in the mobilization of EPCs to pulmonary endothelium and to other tissue after hypoxic-ischemic injury.[47]

Key mechanisms underlying hypoxia and hypoxic adaptation

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) is a critical mediator in hypoxia and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced responses, which is involved in the activation of many cytokines, chemokines, transcription factors, and growth factors in response to hypoxia in almost all kinds of cells.[48,49] HIF-1α was stabilized to upregulate β-catenin transcription in myelogenous leukemia stem cells.[50] Hypoxic adaptation increases the expression of glucose transporter isoform 3 in the neuro-2A neuroblastoma cells through regulation of the activator protein 1, cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), HIF-1α, and hypoxia response element.[51] In hypoxia-treated mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the glucose-6-phosphate transporter is significantly increased through upregulation of HIF-1α, aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), and AhR nuclear translocator.[52] In a γ-radiation model, HIF-1α expression and activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (m-TOR) contribute to the development of radio-resistance.[53] Recent investigations suggest a regulatory role of HIF proteins on microRNA (miRNA) expression under hypoxic conditions. HIF-1α can bind to the placental growth factor (PlGF) promoter and regulate the synthesis for miRNA-214 to target PlGF posttranscription regulation in sickle cell disease and cancer.[54] Hypoxia promotes proliferation of BMSCs, and miRNA-210 was reported to be involved in the BMSC proliferation through an interaction with the HIF pathway.[55] Under lethal OGD, BMSCs also show upregulated miRNA-34a, a pro-apoptotic signal molecule which promotes oxidative stress and causes mitochondrial dysfunction through repressing silent-mating-type information regulation 2 homolog 1 and activating forkhead box O3.[56] Significant changes in hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) might occur during OGD. The CSE/H2S system has thus been considered a potential target to protect BMSCs against apoptosis in transplantation therapy. In neurons after OGD, DJ-1 proteins (encoded by PARK7) translocate into the mitochondria, where mitigation of oxidative stress may mediate neuroprotection after hypoxia and ischemia.[57]

The levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) in the brain after ischemia and in hippocampal slice cultures after OGD are associated with glial activation. MMPs are also migratory factors for stem cells. In humans, hypoxia treatment of CD34+ umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells (UCHSCs) results in the upregulation of cAMP-1-activated exchange protein (Epac-1) and MMPs, facilitating cellular engraftment, migration, and differentiation after transplantation into ischemic brains.[58] MMPs are further subclassified into transmembrane types (MT-1 to MT-3, and MT-5) and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored types (MT-4 and MT-6). When exposed to pro-inflammatory cytokines and hypoxia, the MMP inhibition in BMSCs is mediated by the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1, which is considered an important mechanism to protect the ECM. In vivo studies confirmed the decreased myelin density in the white matter after cerebral hypoperfusion[59,60,61] (e.g., cilostazol, an activator of cyclic AMP, which reversed the white matter loss and promoted oligodendrocyte differentiation). The neuregulin-1 isotype β-1/ErbB4 signaling was involved in protecting oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) during and after a hypoxic event. In hypoxic culturing conditions (3% O2) and methylprednisolone co-treatment, the spinal cord-derived neural progenitors downregulated HIF-1α and the hairy and enhancer of split-1, a downstream Notch signaling mediator. HIF-1α depletion in ES cells showed significant reduction in sex-determining region Y box (SOX)-1 and elevation in BMP-4, supporting the potential mechanism underlying hypoxia-mediated neural commitment and differentiation.

Hypoxic and ischemic preconditioning in vivo

Sublethal ischemia has been demonstrated to be effective for an enhanced tolerance to lethal ischemia in the brain and the heart. Protective effects after hypoxic or ischemic preconditioning involve neural plasticity processes and adaptive responses in the brain. Hypoxia-preconditioned cells and tissue show changes in physiology, neurochemical, and neuroelectrophysical properties.[62] Investigations of sublethal hypoxic pretreatment in vivo as well as in vitro might provide new strategies for the therapy or prevention of CNS disorders and injuries.

Ischemic tolerance in the CNS can be induced by hypoxic preconditioning. In adult animals after fetal tracheal occlusion, the blood pressure could drop to an extremely low level within several minutes, and severe physiological responses might occur. Although respiratory frequency and cardiovascular activity can be regulated to control the oxygen balance, the protective mechanisms after preconditioning hypoxia have been proven to be more than these systemic controls. Repeated autohypoxic models in which animals were placed into sealed chambers have been utilized to study hypoxic tolerance by the measurement of grasping behaviors.[63]

Hypoxia, cancer, and cancer stem cells

Hypoxia is one of the common players in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. The cancer stem cell niche, recently identified in many types of tumors, demonstrates a hypoxic environment for tumor self-renewal. There is evidence that low ROS conditions contribute to the tumor stemness.[64] Hypoxia in tumors may lead to an elevation of octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT-4), the master pluripotency factor, and one of the cancer cell stemness markers.[65] Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF-4), NANOG, and OCT-4 increase dedifferentiation and cell resistance to chemotherapeutic agents and hypoxic injury.[66,67] In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells, hypoxia can significantly upregulate nestin through transforming growth factor β-1 (TGFβ-1)/mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD-4) signaling.[68] Hypoxia induces CD24 (a marker for tumor formation and metastasis) through HIF-1α binding to the promoter in many cancers.[69] HIF-1α and the MT-1 MMP signaling has been also identified for oncogenic cell migration.[70] In medulloblastoma cells, hypoxia can stabilize the interactions between HIF-1α and Notch proteins, causing an expansion of CD133+/nestin+ cell subpopulations.[71] In melanoma cells, HIF induction, in response to hypoxia, results in greater melanoma proliferation, migration, and metastasis through SNAIL1 activation and E-cadherin downregulation.[72] Cobalt chloride (CoCl2) exposure (to mimic the effect of hypoxia) activates HIF-1α/pAkt and upregulates genes required for metabolite transport and metabolism in tumor cells (such as glioblastomas). The miRNA regulation may be involved in the maintenance of the cancer stem cell phenotype.[73,74] One of the HIF-regulating factors, EPO, has been shown to promote tumorigenesis by activating Janus kinase (JAK)/STAT signaling.[75] In Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg tumor cells, Notch-1 and JAK/STAT pathway are activated, whose inhibition results in apoptosis for treating classical Hodgkin lymphoma.[76] In an experimental glioma model, tumor cells expressed CD133, nestin, VEGF, sodium calcium ex-changers, and showed hybrid cell death after chemotherapy drug treatment.[77,78] Hypoxia also inhibits HIF-1α degradation, which is BMP dependent.[79] Further studies suggest HIF-1 and VEGF as two angiogenic targets that can be used for diagnosis and blocked for treating cancers.[80,81,82] Anthracycline chemotherapy is effective in inhibiting HIF-1, which blocks the mobilization of circulating progenitors to the tumor angiogenesis.[83]

STEM CELLS AND CELL THERAPY

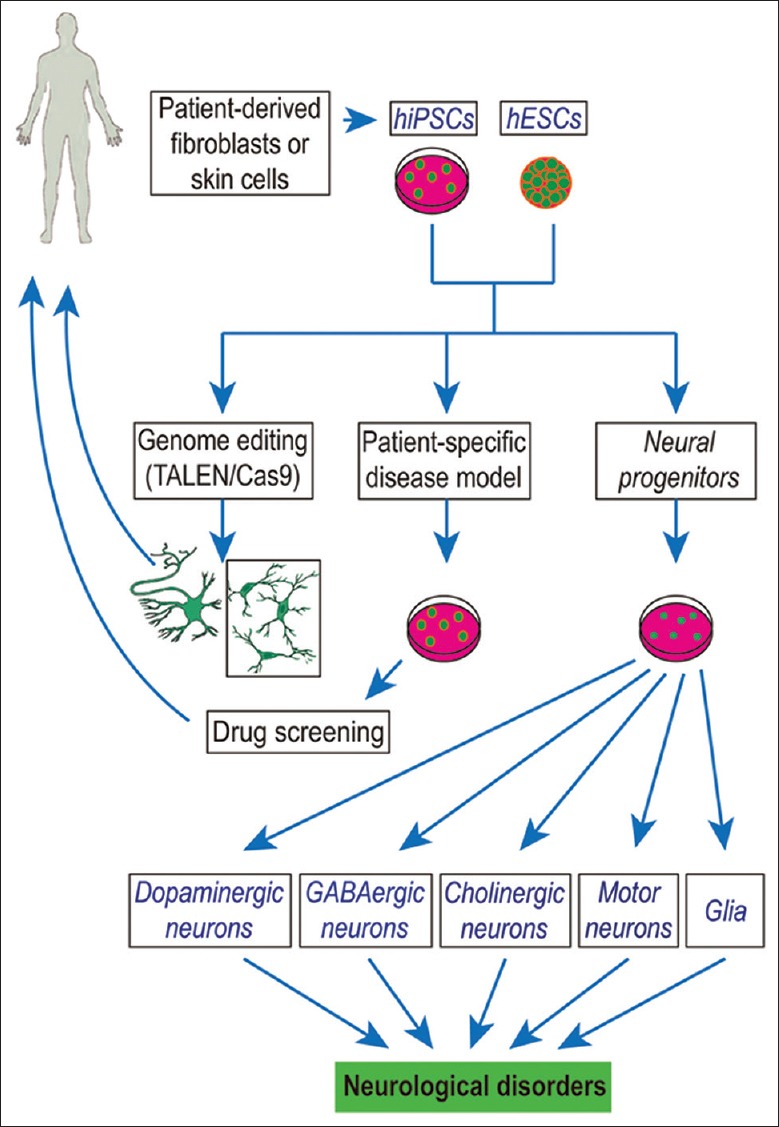

Stem cells are major sources of cell-based therapy [Figure 1]. They can be classified as totipotent cells, naïve pluripotent stem cells, primed pluripotent cells, and tissue-specific multipotent stem cells. Totipotent cells, characteristic of the zygote and early blastomeres, can develop into all tissues, including extra-embryonic tissue. While both naïve and primed pluripotent cells can form a teratoma, the two different pluripotent states have distinct molecular differences. Naïve stem cells are in a ground state, harboring the prerequisite potential to differentiate into all embryonic lineages and develop into chimeric blastocysts. It possesses high clonogenicity and does not carry specification markers.[84] Primed pluripotent cells, which do not produce chimeras, express FGF-5 specification marker and have low clonogenicity. For pluripotency markers, naïve stem cells display greater levels of pluripotency marker proteins, including OCT-4, NANOG, SOX-2, KLF-2, and KLF-4, while primed cells lose KLF-2 and KLF-4 expression. Aside from the naïve and primed pluripotent states, a study discovered an intermediate pluripotent stage between the two states.[85] The tissue-specific multipotent stem cell has the least differentiating potency among all stem cell types, with the ability to form tissue-specific cell types.[86,87]

Figure 1.

Human ESCs- and iPSCs-derived neuronal and glial cell therapeutics. This sketch shows the potential use of human ESCs- and iPSCs-derived neuronal and glial cells to treat the neurological disorders. ESCs: Embryonic stem cells; iPSCs: Induced pluripotent stem cells; TALEN: Transcription activator-like effector nucleases.

Human embryonic stem cells

The success in generation and culture of ESCs from mice, primates, and human embryos has been considered a milestone of stem cell research. ESCs are a useful tool for exploring early embryonic development, modeling pathological processes of diseases, and developing therapeutics through drug discovery and potential cell replacement.[88,89,90] The human ESCs (hESCs) now hold a great promise for regenerative medical treatments as the cells can generate any cell type of the body. The hESCs are mainly defined as primed pluripotent cells, which are different from and show less plasticity than the murine ESCs. It remains unclear whether human-naïve pluripotent stem cells, obtained either by continued transgene expression or through specific chemical manipulation of the culturing microenvironment, are analogous to mouse counterparts.[91,92,93,94,95] Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to validate the findings from these reports using naïve hESCs generated from different strains and laboratories in future studies.

Differentiation of hESCs in vitro has been achieved at very high efficiencies into various transplantable progenitors/precursors and terminally differentiated neuronal and glial cell types, which include cortical glutamatergic, striatal γ-aminobutyric acid gamma aminobutyric acid-ergic, forebrain cholinergic, midbrain dopaminergic, serotonergic, and spinal motor neurons, as well as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes.[96,97,98,99,100,101,102] These differentiated cells, including neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, have been exogenously transplanted and evaluated in animal models. Translation into the clinic is ongoing for various neurological disorders, including: (1) PD, in which nigro-striatal neurons are lost before other neurons, (2) HD, in which MSNs are lost, resulting in striatal atrophy, and (3) glial and myelin disorders.[103,104,105,106] Other disorders, including AD and Lewy body disease, which involve a multitude of neuronal cell types, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and spinal muscular atrophy, which are multicentric and diffuse neurodegenerative disorders, remain poor targets for stem cell-based therapies. To date, it is widely accepted that glial metabolic deficiencies might contribute to disease progression in ALS, in which neurons might be the paracrine victims of glial dysfunction. As such, cell-based treatment approaches for ALS and other neurodegenerative disorders have thus shifted the focus away from neuronal replacement toward glial replacement.[107] If successful, such studies might herald the application of hESC-derived glia for treating ALS and related disorders.

Induced pluripotent stem cells

The iPSCs are pluripotent cells that are artificially de-differentiated from adult somatic cells by several transcription factors or small-molecule compounds and have ignited the field of lineage reprogramming.[108,109] There are epigenetic differences between iPSCs and ESCs, which include expressions of unique genetic signatures, teratoma formation capacity, and the differentiation potency and flexibility (e.g., dissimilar differentiation potential into various transplantable neural cells[110]). Furthermore, compared to ESCs, iPSCs can be more amenable as donor cells for cell replacement therapy, in vitro disease models, and drug screening.[111,112,113] First, iPSCs are derived from adult somatic cells, which can be easily obtained from patients, and then banked and stored. Second, cultures of hiPSCs and hESCs are technically similar, but the generation of iPSCs harbors much less ethical concern and opposition.[114] Third, given the somatic cell source and the autologous nature of iPSCs, cell therapy using iPSCs should have no immune rejection in theory, or at least minimize the risk of immune system rejection. However, a recent report suggests that some unusual gene expressions in transplanted cells derived from the iPSCs may trigger an immune response.[115]

The miPSCs and hiPSCs provide a powerful tool for developmental biology research and translational medicine. To develop and achieve fast improvement in pharmaceutical agents, iPSCs combined with microfluidic technology have provided bio-screening platforms, allowing for high-throughput preclinical drug screening and advancing the search for new pharmacological therapies. Furthermore, iPSCs allow for greater experimental interrogation and convenience compared to transgenic animal models when determining clinically relevant doses and the short- and long-term adverse effects.

One of the most exciting features of iPSCs is the potential use of reprogrammed somatic cells to establish disease-relevant phenotypes in vitro and to simulate and recapitulate the molecular signatures of pathogenesis in an early stage. This has been implemented in a variety of neurological disorders, such as familial dysautonomia, Rett syndrome, HD, AD, ALS, PD, and schizophrenia.[116,117,118,119,120,121] According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-established ethical guidelines and standards, the hiPSC repositories of personalized cell lines from patients can be developed and banked, and the iPSC technology can be used to model disease and screen drugs. Genetic modifications or enhancements of patient iPSCs are being tested (e.g., reinfusion treatment for patients with sporadic diseases). Genome editing of hiPSCs uses programmable nucleases including transcription activator-like effector nucleases and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats Cas9 technology.[122,123,124] Genome editing has greatly expanded our vision for understanding of pathological processes by studying cellular/disease models, and human cells and tissue, in which the programmable nucleases can directly correct/introduce genetic mutations. Compared to traditional drug therapy, therapeutic genome editing strategies provide an alternative method to treat both genetic diseases and diseases with genetic and environmental factors, such as hemophilia and severe combined immunodeficiency.[125] A combination therapy with iPSCs and genome editing is proposed as a new therapy to introduce protective mutations, to correct deleterious mutations, to eliminate the antigenic/immunogenic signals in the iPSCs, or to destroy foreign viral DNAs in the human body.[126] In the absence of exogenous template DNA, the programmable nucleases create a double strand break (DSB) in desired regions, but due to the error-prone nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) mechanism of re-ligation, an insertion/deletion (indel) mutation is frequently created at the DSB site. NHEJ-based genome editing has been tested in several proof-of-concept studies for treating genetic diseases. The reported editing on fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR-3) for achondroplasia and dystrophin for Duchenne muscular dystrophy specifically inactivated the mutant allele, corrected the disease mutation, and shut down the expression of pathogenic gene product.[127] Another example was to treat trinucleotide repeat disorders, such as fragile X syndrome and HD. To ablate the triple repeats, a pair of single-guide RNAs was applied to target both sides during the expansion. NHEJ-based genome editing antagonized a viral infection in several proof-of-concept experiments including hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus.[128,129,130] Other than NHEJ, the high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR)-based mechanism of genome editing was studied to treat deleterious loss-of-function mutations, such as cystic fibrosis and β-thalassemia. HDR-based genome editing provides an exogenous repair template of a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide and a donor plasmid to correct a mutated allele to be wild type. It could also integrate therapeutic transgenes into a genomic safe harbor site.

Mesenchymal stem cells

MSCs derived from the bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, and adipose tissue could exert immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects in CNS disease models such as stroke and MS.[131] The bone marrow-derived MSCs were shown to promote neuronal survival and remove amyloid plaques in a rat AD model.[132] Overexpression of some neurogenic/angiogenic factors such as VEGF in the transplanted MSC cells might help improve memory and induce neovascularization/neurogenesis within the adult brains. Clinical trials demonstrated safety and feasibility of MSC transplantation in acute and chronic stroke with no tumorigenicity reported following cellular transplantation.[133]

Fetal neural progenitor cells

Fetal NPCs, which can differentiate into functional neurons and multiple types of neuroglia, are an ideal platform to bridge the gap between traditional model systems and human biology.[134,135,136,137] The differentiation of fetal hNPCs in vitro could recapitulate brain development. Recent efforts intending to measure the transcriptome from the fetal human brain provide an unbiased in vivo standard using single-cell approaches and genome-wide transcriptome analyses.[138,139] The studies suggested that the fetal hNPCs have a stronger matching genomic overlap with the in vivo cortex compared to hiPSCs, allowing for the identification of specific neurodevelopmental processes related to pathophysiology of developmental disorders. Fetal hNPCs were investigated in clinical trials for the treatment of spinal cord injury (SCI) and AMD, but the safety has not yet been verified.

PRECONDITIONING IN STEM CELL THERAPY

Hypoxia-regulated cell differentiation and regeneration

NSC phenotypes and repair mechanisms have been studied as a regenerative therapy in CNS diseases. Normally, hypoxic conditions and intracellular ROS levels help maintain the proliferation and self-renewal of NSCs in the brain.[140] HIF-1α overexpression can promote NSC proliferation and differentiation after intracerebral hemorrhage and hypoxic/ischemic injury. HIF-1α has been shown to promote the ESC differentiation into dopaminergic neurons.[141] Studies about hippocampal CA1 neurogenesis suggest that the attenuated Notch-1 signaling by an inhibitor of γ-secretase might determine the neuronal lineage differentiation. Leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 are dramatically increased after hypoxic-ischemic injury, which activate LIF receptor (LIFR)/glycoprotein (gp130) and Notch-1 for expansion of NSCs in the brain.[142] Metformin, a well-tolerated oral medication, promotes adult neurogenesis through activation of atypical protein kinase C/CREB-binding protein pathway. Preclinical studies using hypoxic-ischemic injury models have shown that treatment using metformin can alleviate sensorimotor defects and reduce ischemia-reperfusion injury.[143,144]

Hypoxia-ischemia has been shown to cause accumulation of HIF-1α and an increase in VEGF/VEGFR in endothelial cells and EPO/EPOR in glial cells.[145,146,147] In hypoxic conditions of 3% oxygen, upregulation of angiogenic factors (such as angiotensin II [Ang II], angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE], and Ang II receptor Type 1 [AT1R]) and some specification transcriptional factors (such as the SOX-2) was observed. Ang II pretreatment activated the AT1R/HIF-1α/ACE axis in rat BMSCs and promoted VEGF production and the angiogenic response. Co-culturing of stem cells from apical papilla and human umbilical venous endothelial cells resulted in the formation of endothelial tubules, which was bolstered by hypoxic conditions.[148] Involvement of miRNA-31 and miRNA-720 in vascularization by EPCs was also reported in coronary artery disease, and this phenomenon was directed by HIF-1α signaling.

Glial progenitor cells in the SVZ and the white matter are activated and expanded after ischemia, and this can be further augmented by treatments, including uridine diphosphoglucose glucose, GDNF, epidermal growth factor, EPO, or memantine to differentiate into oligodendrocytes.[149,150] Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonates induces cell death in committed neural precursors but stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of immature neural progenitors for brain repairs.[151] Transplantation of stem cells such as UCBMCs might promote the proliferation and neuronal differentiation of endogenous NSCs. Neurogenin-1 upregulation and BMP-4 downregulation have been identified as putative mediators of these activities.[152]

Hypoxia-ischemia induces repair mechanisms of endogenous stem cells, and more recently identified, stemness of resident cells via reprogramming.[153] In MSCs, hypoxia regulates miRNA-302, which supports their reprogramming into pluripotent states. The combination of hypoxia and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) together induces the expression of OCT-4 and NANOG in L87 cells and primary MSCs.[154] After inhibition by FGF-2, the proliferation of human MSCs is inhibited, leading to an osteogenic or an adipogenic differentiation.[155] In 2% oxygen conditions and ECM adhesion, viability and multi-potentiality can be preserved in transplantation therapy. In slice culture models, hypoxic preexposure will markedly reduce the survival of seeded stem cells on the slices. Methylprednisolone, a widely used glucocorticoid or corticosteroid drug, inhibits the endogenous brain repair mechanisms after treating SCI through changing a variety of growth and angiogenic factors.[156] Maintaining NSC renewal by drug-inducing Notch-1, OCT-4, and SOX-2 expressions may promote regeneration after SCI.[157] Differentiation and survival of progenitor/stem cells might also be affected in hypoxic, starvation, and ischemic conditions.

An ischemic insult to the cortex can markedly increase the expression of SDF-1 in the ischemic region, which is a chemoattractant for directional migration of neuroblasts expressing CXCR-4.[158] Hypoxia can induce migration in various types of cells, including BMSCs, cardiac SCA-1+ progenitors, ESCs/iPSCs, NSCs, and many tumor cells.[159,160,161,162,163] The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis and hypoxia are mediators for BMSC/EPC migration in the bone marrow, the peripheral blood, and many other organs.[83,164,165] Upon hypoxic stimuli, IL-8 is upregulated and activated in acute myeloid leukemia immune cells, which show greater migration out of the stem cell niche.[166]

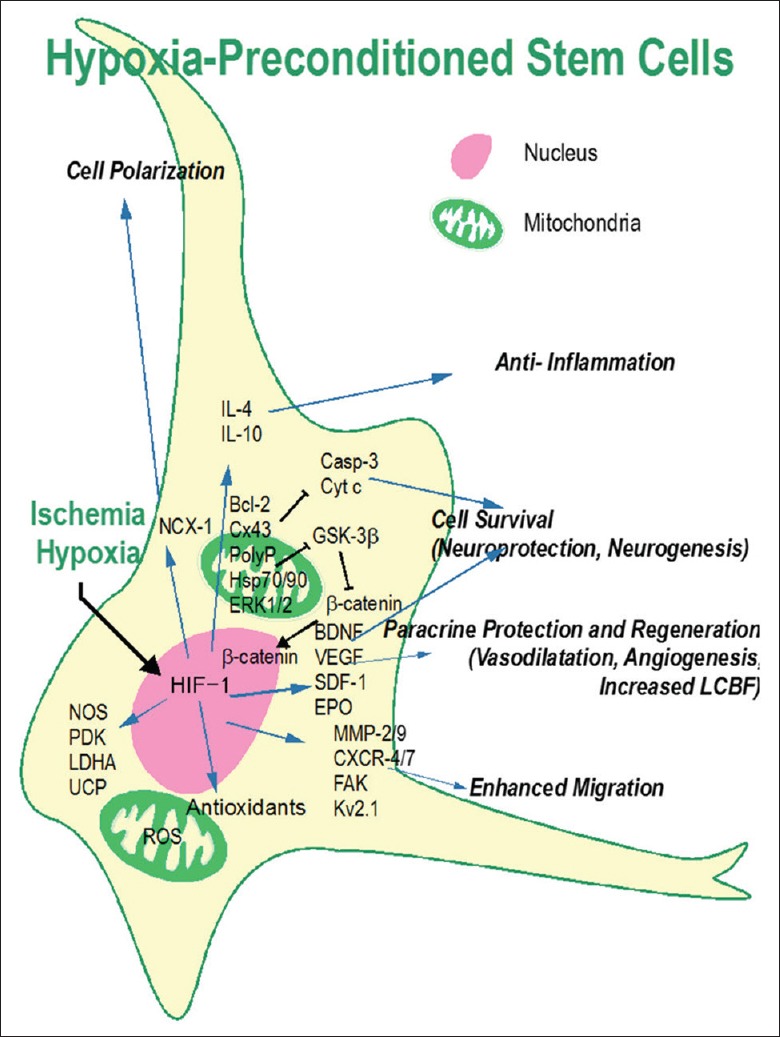

Transplantation of stem cells

Stem cell transplantation holds a great promise for vascular diseases and many other degenerative disorders.[167,168,169] As a therapeutic goal for cell transplantation, stimulated angiogenesis ameliorates hypoxia and provides nutrient support, which might help functional recovery through regenerative mechanisms. Transplantation of BMSCs in the acute phase exerts neuroprotective benefits after ischemia. Our group and others demonstrated that hypoxic-preconditioned BMSCs and neural progenitors showed significant increases in the survival of transplanted cells, homing to the lesion sites, neuronal differentiation, and functional benefits after stroke.[42,159,163,170] Multiple cellular and molecular mechanisms and the beneficial effects of transplantation of hypoxic-preconditioned cells were summarized in previous reviews[2,171] [Figure 2]. More recently shown in different animal models, hypoxic preconditioning combined with IL-7 overexpression in rat BMSCs was shown to increase the migration capacity and fusion potential with renal epithelial cells.[172] Hypoxic preconditioning might also combine with other anti-apoptotic/oxidative stress pretreatment on MSCs to show greater fusion with host cells and regenerating capacity after ischemia or for treating diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Recent studies have attempted to use conditioned medium from OGD-treated neurons to precondition human UCMSCs, showing greater pro-angiogenic effects.[173] Conditioned medium from UCMSCs subjected to hypoxia could further enhance mitogenic activity of cardiac SCA-1+ progenitors, indicating a paracrine mechanism.[174] Hypoxia-treated hMSCs contain an enriched secretome of trophic factors which might provide a suitable preconditioning strategy for enhanced differentiation of NPCs after transplantation.[175]

Figure 2.

Mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of hypoxic preconditioning. The hypoxic preconditioning strategy was designed to mimic and utilize endogenous protective mechanisms to promote neuroprotection, tissue regeneration, and brain function recovery. Hypoxic preconditioning directly induces HIF-1 upregulation that increases BDNF, SDF-1, VEGF, EPO, and many other genes which can stimulate neurogenesis, angiogenesis, vasodilatation, and increase cell survival. HIF-1 expression regulates antioxidants, survival signals, and other genes related to cell adhesion, polarization, migration, and anti-inflammatory responses. Partially adapted from a previous publication (Wei L, et al. Stem cell transplantation therapy for multifaceted therapeutic benefits after stroke. Prog Neurobiol 2017.). AhR: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; AP-1: Activator protein 1; ARNT: AhR nuclear translocator; ASC: Adipose tissue-derived stromal stem cell; BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMP-4: Bone morphogenetic protein 4; BMSC: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell; Casp: Caspase; CBP: CREB-binding protein; CNS: Central nervous system; CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein; Cx43: Connexin 43; CSE: Cystathionine γ-lyase; CXCR-4: CXC chemokine receptor 4; Cyt c: Cytochrome c; Epac: Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP; EGF: Epidermal growth factor; EPC: Endothelial progenitor cell; EPO: Erythropoietin; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ESC: Embryonic stem cell; FAK: Focal adhesion kinase; FGF-2: Fibroblast growth factor-2; FoxO-3: Forkhead box O3; GDNF: Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; G-6-PT: Glucose-6-phosphate transporter; GLUT-3: Glucose transporter isoform-3; GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta; H2S: Hydrogen sulfide; Hes1: Hairy and enhancer of split 1; H/I: Hypoxia-ischemia; HIF-1α: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha; HRE: Hypoxia response element; Hsp: Heat shock protein; IL-10: Interleukin 10; JAK: Janus kinase; LIF: Leukemia inhibitory factor; LIFR: LIF receptor; miRNAs: microRNAs; MECP2: Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2; MIF: Migration inhibitory factor; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinase; MSCs: Mesenchymal stem cells; N2A: Neuro 2A; NCX-1: Sodium–calcium exchanger-1; NGN-1: Neurogenin-1; NOS: nitric oxide synthase; NSC: Neural stem cell; OCT-4: Octamer-binding transcription factor-4; OGD: Oxygen-glucose deprivation; OPC: Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell; PDAC: Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PDK: Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PlGF: Placental growth factor; polyP: Polyphosphate; RasGAP: Ras-GTPase-activating protein; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; SCA-1: Stem cell antigen-1; SCAP: Stem cell from apical papilla; SCI: Spinal cord injury; SDF-1: Stromal-derived factor-1; STAT-3: Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3; SIRT-1: Silent-mating-type information regulation 2 homolog-1; SVP: Saphenous vein-derived pericyte; SVZ: Subventricular zone; TGFβ-1: Transforming growth factor β-1; TIMP-1: Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase; UCHSCs: Umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells; UDPG: Uridine diphosphoglucose-glucose; UCP: Uncoupling protein; UVECs: Umbilical venous endothelial cells; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor.

Transplantation of BMSCs engineered with miRNA-377 along with direct repression of VEGF transcription showed significantly reduced vessel density and increased fibrosis in the infarcted myocardium.[176] Delivery of saphenous vein-derived pericyte progenitor cells in myocardial infarction models demonstrates a novel role of miRNA-132 in paracrine activation by targeting Ras-GTPase-activating protein and methyl-CpG-binding protein 2.[177] Stem cells cultured in hypoxic conditions show enhanced differentiation potential. Compared to 20% oxygen in vitro conditions, vascularization by the adipose-derived stromal stem cells (ASCs) was significantly decreased in moderate (2% oxygen) and severe (0.2% oxygen) hypoxia conditions.[178] Interestingly, this in vitro test showed an unchanged level of VEGF, indicating an independent pathway for the angiogenesis control.[178] Another group showed that severe hypoxia (0.2% oxygen) dramatically increased both transcriptional and translational levels of VEGF-A and Ang in ASCs.[179] Released VEGF-A was an apoptosis inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle cells controlled by TGF-β/SMAD-3.[179] Sublethal CoCl2 treatment on OPC induced a chemical hypoxic stress and suppressed the oligodendroglial differentiation.[180] CoCl2(0.5 mmol/L) also increased Eph family receptor-interacting protein B2 (ephrin B2), HIF-1α, and VEGF.

As a means of improving survival and oxidative resistance of BMSCs for transplantation therapy, chemical preconditioning (e.g., H2S, LPA, MIF, and pitavastatin) has been suggested.[170,181] A three-dimensional culture of cardiac SCA-1+ progenitors showed improved cell survival under hydrogen peroxide and anoxia/reoxygenation in the ischemic heart after transplantation.[182] An elevation of Sonic hedgehog, Wnt, and BDNF signaling in the SVZ or transplanted cells may promote the regenerative processes of neural progenitors in hypoxic-ischemic injury models.[183,184] Following adipose stem cell transplantation, animals housed in an environment allowing voluntary physical exercises showed even better functional recovery after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury.[185] Co-treatment of rat BMSCs with laminin micro-carriers releasing angiogenic VEGF shows some synergistic effects, including angiogenesis and enhanced immature neuron migration toward ischemic core regions.[186] Combination therapy using viral VEGF overexpression and BMSCs might result in the smallest size of infarct and the best functional recovery. Many other growth factors (FGF, GDF-5, IGF-1, and TGF-β) have been suggested for combination therapy with cell transplantation to treat intervertebral disc degeneration and enhancing nucleus pulposus-like differentiation of MSCs.[187]

CONCLUSIONS

Stem cell research has made a rapid progress and great hope for treating a wide spectrum of neurological disorders. Expansion of the repertoire of available stem cell subtypes and an increased understanding of their differentiation potency bring us one step closer toward clinical translation. Furthermore, stem cell models provide far-reaching applications for translational medicine studies, including in vitro disease models to elucidate developmental and pathological mechanisms. Exogenous stem cells and NPCs investigated for treating neurological disorders originate from a variety of sources, including ESCs derived from the inner mass of blastocysts, iPSCs reprogrammed from somatic cells, MSCs, or even adult NS/NPCs.[188] In addition, a combination of hESCs and hiPSCs with gene-editing technologies might provide enhanced cell replacement, trophic support, drug delivery, and immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. Many clinical trials are under way. Transplantation of lineage-committed cells and the control in the quality and number of transplanted cells have eliminated the risk of tumorigenesis. Efforts are still needed to detect and eliminate cancer stem cells and continuously prevent tumor formation. Another concern is that the cells after transplantation might trigger transplant rejection by the immune system in the long term. This concern is partially resolved now by utilizing autologous iPSCs reprogrammed from the host's own somatic cells. Increasing evidence also suggests that MSCs are low immunogenicity cells and show immunosuppressing effects after transplantation.[189] Other issues include optimization of the transplantation window and anatomic site, as well as generation of pure and specific differentiated cells. Hypoxic and ischemic models have been widely used in the research and development of new drugs and clinical therapy. Preconditioning benefits are induced by an adaptation after a sublethal stimulus and an enhanced resistance to the lethal injury, with many survival and regenerative genes involved. Among them, the upstream signaling mediators, especially HIF-1α, might have a great potential as targets for drug development for neuroprotection and neuroregeneration. Transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned cells appears to be the first feasible strategy to take the advantage of hypoxic tolerance in clinical applications. Furthermore, preconditioning treatments on remote tissues or organs (remote preconditioning) demonstrate great therapeutic efficacy with a high translational potential. While they both serve therapeutic purposes individually, hypoxic preconditioning and stem cell therapy display tremendous synergistic effects together that warrant further preclinical and eventually clinical studies.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81371355, No. 81500989, and No. 81671191), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 7142045), the NIH grants (No. NS062097, No. NS085568, and No. NS091585).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Peng Lyu

REFERENCES

- 1.Jaenisch R, Young R. Stem cells, the molecular circuitry of pluripotency and nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2008;132:567–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei L, Wei ZZ, Jiang MQ, Mohamad O, Yu SP. Stem cell transplantation therapy for multifaceted therapeutic benefits after stroke. Prog Neurobiol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.03.003. pii: S0301-008230115-0. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang MQ, Zhao YY, Cao W, Wei ZZ, Gu X, Wei L, et al. Long-term survival and regeneration of neuronal and vasculature cells inside the core region after ischemic stroke in adult mice. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:480–98. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12425. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei L, Yu SP, Gottron F, Snider BJ, Zipfel GJ, Choi DW. Potassium channel blockers attenuate hypoxia-and ischemia-induced neuronal death in vitro and in vivo. Stroke. 2003;34:1281–6. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065828.18661.FE. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000065828.18661.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox IJ, Daley GQ, Goldman SA, Huard J, Kamp TJ, Trucco M. Stem cell therapy. Use of differentiated pluripotent stem cells as replacement therapy for treating disease. Science. 2014;345:1247391. doi: 10.1126/science.1247391. doi: 10.1126/science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabar V, Studer L. Pluripotent stem cells in regenerative medicine: Challenges and recent progress. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:82–92. doi: 10.1038/nrg3563. doi: 10.1038/nrg3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinbeck JA, Studer L. Moving stem cells to the clinic: Potential and limitations for brain repair. Neuron. 2015;86:187–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.002. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Chen S, Li JY. Human induced pluripotent stem cells in Parkinson's disease: A novel cell source of cell therapy and disease modeling. Prog Neurobiol. 2015;134:161–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.009. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirschenbaum B, Nedergaard M, Preuss A, Barami K, Fraser RA, Goldman SA. In vitro neuronal production and differentiation by precursor cells derived from the adult human forebrain. Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:576–89. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.6.576. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.6.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pincus DW, Keyoung HM, Harrison-Restelli C, Goodman RR, Fraser RA, Edgar M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2/brain-derived neurotrophic factor-associated maturation of new neurons generated from adult human subependymal cells. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:576–85. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430505. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy NS, Wang S, Jiang L, Kang J, Benraiss A, Harrison-Restelli C, et al. In vitro neurogenesis by progenitor cells isolated from the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 2000;6:271–7. doi: 10.1038/73119. doi: 10.1038/73119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004;427:740–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst A, Frisén J. Adult neurogenesis in humans- common and unique traits in mammals. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst A, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Perl S, Tisdale J, et al. Neurogenesis in the striatum of the adult human brain. Cell. 2014;156:1072–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.044. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergmann O, Liebl J, Bernard S, Alkass K, Yeung MS, Steier P, et al. The age of olfactory bulb neurons in humans. Neuron. 2012;74:634–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergmann O, Spalding KL, Frisén J. Adult neurogenesis in humans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a018994. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018994. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei ZZ, Zhang JY, Taylor TM, Gu X, Zhao Y, Wei L. Neuroprotective and regenerative roles of intranasal Wnt-3a administration after focal ischemic stroke in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0271678X17702669. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1177/0271678x17702669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Wei ZZ, Zhang JY, Zhang Y, Won S, Sun J, et al. GSK-3ß inhibition induced neuroprotection, regeneration, and functional recovery after intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke. Cell Transplant. 2017;26:395–407. doi: 10.3727/096368916X694364. doi: 10.3727/096368916x694364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sultan S, Li L, Moss J, Petrelli F, Cassé F, Gebara E, et al. Synaptic integration of adult-born hippocampal neurons is locally controlled by astrocytes. Neuron. 2015;88:957–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.037. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parent JM, Vexler ZS, Gong C, Derugin N, Ferriero DM. Rat forebrain neurogenesis and striatal neuron replacement after focal stroke. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:802–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.10393. doi: 10.1002/ana.10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song M, Yu SP, Mohamad O, Cao W, Wei ZZ, Gu X, et al. Optogenetic stimulation of glutamatergic neuronal activity in the striatum enhances neurogenesis in the subventricular zone of normal and stroke mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;98:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.11.005. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton LK, Dufresne M, Joppé SE, Petryszyn S, Aumont A, Calon F, et al. Aberrant lipid metabolism in the forebrain niche suppresses adult neural stem cell proliferation in an animal model of Alzheimer's disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.001. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villeda SA, Luo J, Mosher KI, Zou B, Britschgi M, Bieri G, et al. The ageing systemic milieu negatively regulates neurogenesis and cognitive function. Nature. 2011;477:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10357. doi: 10.1038/nature10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katsimpardi L, Litterman NK, Schein PA, Miller CM, Loffredo FS, Wojtkiewicz GR, et al. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science. 2014;344:630–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141. doi: 10.1126/science.1251141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim DA, Alvarez-Buylla A. Adult neural stem cells stake their ground. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:563–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.006. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollis ER, 2nd, Ishiko N, Yu T, Lu CC, Haimovich A, Tolentino K, et al. Ryk controls remapping of motor cortex during functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:697–705. doi: 10.1038/nn.4282. doi: 10.1038/nn.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollis ER, 2nd, Ishiko N, Pessian M, Tolentino K, Lee-Kubli CA, Calcutt NA, et al. Remodelling of spared proprioceptive circuit involving a small number of neurons supports functional recovery. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6079. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7079. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13007–16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-06.2006. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4323-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan YP, Sailor KA, Lang BT, Park SW, Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1213–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babona-Pilipos R, Droujinine IA, Popovic MR, Morshead CM. Adult subependymal neural precursors, but not differentiated cells, undergo rapid cathodal migration in the presence of direct current electric fields. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi T, Ahlenius H, Thored P, Kobayashi R, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Intracerebral infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor promotes striatal neurogenesis after stroke in adult rats. Stroke. 2006;37:2361–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000236025.44089.e1. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000236025.44089.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Jiang M, Xu C, Chen J, Li B, Wang J, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-primed bone marrow: An excellent stem-cell source for transplantation in acute myelocytic leukemia and chronic myelocytic leukemia. Chin Med J. 2015;128:20–4. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.147790. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.147790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawada H, Takizawa S, Takanashi T, Morita Y, Fujita J, Fukuda K, et al. Administration of hematopoietic cytokines in the subacute phase after cerebral infarction is effective for functional recovery facilitating proliferation of intrinsic neural stem/progenitor cells and transition of bone marrow-derived neuronal cells. Circulation. 2006;113:701–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.563668. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.563668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benraiss A, Toner MJ, Xu Q, Bruel-Jungerman E, Rogers EH, Wang F, et al. Sustained mobilization of endogenous neural progenitors delays disease progression in a transgenic model of Huntington's disease. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:787–99. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.014. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang R, Chopp M. Treatment of stroke with erythropoietin enhances neurogenesis and angiogenesis and improves neurological function in rats. Stroke. 2004;35:1732–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000132196.49028.a4. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000132196.49028.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoehn BD, Palmer TD, Steinberg GK. Neurogenesis in rats after focal cerebral ischemia is enhanced by indomethacin. Stroke. 2005;36:2718–24. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190020.30282.cc. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000190020.30282.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang LL, Chen D, Lee J, Gu X, Alaaeddine G, Li J, et al. Mobilization of endogenous bone marrow derived endothelial progenitor cells and therapeutic potential of parathyroid hormone after ischemic stroke in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang YL, Zhu W, Cheng M, Chen L, Zhang J, Sun T, et al. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the benefit of cardiac progenitor cell therapy for treatment of myocardial infarction by inducing CXCR4 expression. Circ Res. 2009;104:1209–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197723. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.109.197723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shyu WC, Liu DD, Lin SZ, Li WW, Su CY, Chang YC, et al. Implantation of olfactory ensheathing cells promotes neuroplasticity in murine models of stroke. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2482–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI34363. doi: 10.1172/jci34363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jellema RK, Lima Passos V, Ophelders DR, Wolfs TG, Zwanenburg A, De Munter S, et al. Systemic G-CSF attenuates cerebral inflammation and hypomyelination but does not reduce seizure burden in preterm sheep exposed to global hypoxia-ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2013;250:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.09.026. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu SP, Lee SD, Lee HT, Liu DD, Wang HJ, Liu RS, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor activating HIF-1alpha acts synergistically with erythropoietin to promote tissue plasticity. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song M, Mohamad O, Gu X, Wei L, Yu SP. Restoration of intracortical and thalamocortical circuits after transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells into the ischemic brain of mice. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:2001–15. doi: 10.3727/096368912X657909. doi: 10.3727/096368912x657909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun H, Yang HL. Calcium phosphate scaffolds combined with bone morphogenetic proteins or mesenchymal stem cells in bone tissue engineering. Chin Med J. 2015;128:1121–7. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.155121. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.155121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma HC, Wang X, Wu MN, Zhao X, Yuan XW, Shi XL. Interleukin-10 contributes to therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells for acute liver failure via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling pathway. Chin Med J. 2016;129:967–75. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.179794. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.179794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tepeköylü C, Wang FS, Kozaryn R, Albrecht-Schgoer K, Theurl M, Schaden W, et al. Shock wave treatment induces angiogenesis and mobilizes endogenous CD31/CD34-positive endothelial cells in a hindlimb ischemia model: Implications for angiogenesis and vasculogenesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:971–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.01.017. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsboom G, Pokreisz P, Gheysens O, Vermeersch P, Gillijns H, Pellens M, et al. Sustained endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction after chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1017–26. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0562. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satoh K, Kagaya Y, Nakano M, Ito Y, Ohta J, Tada H, et al. Important role of endogenous erythropoietin system in recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. Circulation. 2006;113:1442–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583732. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.583732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang M, Nguyen P, Jia F, Hu S, Gong Y, de Almeida PE, et al. Double knockdown of prolyl hydroxylase and factor-inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor with nonviral minicircle gene therapy enhances stem cell mobilization and angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124 11 Suppl:S46–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014019. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.110.014019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogle ME, Yu SP, Wei L. Primed for lethal battle: A step forward to enhance the efficacy and efficiency of stem cell transplantation therapy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:527. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.06.003. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giambra V, Jenkins CE, Lam SH, Hoofd C, Belmonte M, Wang X, et al. Leukemia stem cells in T-ALL require active Hif1a and Wnt signaling. Blood. 2015;125:3917–27. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-609370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-609370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thamotharan S, Raychaudhuri N, Tomi M, Shin BC, Devaskar SU. Hypoxic adaptation engages the CBP/CREST-induced coactivator complex of Creb-HIF-1a in transactivating murine neuroblastic glucose transporter. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E583–98. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00513.2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00513.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lord-Dufour S, Copland IB, Levros LC, Jr, Post M, Das A, Khosla C, et al. Evidence for transcriptional regulation of the glucose-6-phosphate transporter by HIF-1alpha: Targeting G6PT with Mumbaistatin analogs in hypoxic mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:489–97. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0855. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salama S, Diaz-Arrastia C, Patel D, Botting S, Hatch S. 2-Methoxyestradiol, an endogenous estrogen metabolite, sensitizes radioresistant MCF-7/FIR breast cancer cells through multiple mechanisms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.080. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonsalves CS, Li C, Mpollo MS, Pullarkat V, Malik P, Tahara SM, et al. Erythropoietin-mediated expression of placenta growth factor is regulated via activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a and post-transcriptionally by miR-214 in sickle cell disease. Biochem J. 2015;468:409–23. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141138. doi: 10.1042/bj20141138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang HW, Huang TS, Lo HH, Huang PH, Lin CC, Chang SJ, et al. Deficiency of the microRNA-31-microRNA-720 pathway in the plasma and endothelial progenitor cells from patients with coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:857–69. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303001. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.113.303001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang F, Cui J, Liu X, Lv B, Liu X, Xie Z, et al. Roles of microRNA-34a targeting SIRT1 in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:195. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0187-x. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaneko Y, Tajiri N, Shojo H, Borlongan CV. Oxygen-glucose-deprived rat primary neural cells exhibit DJ-1 translocation into healthy mitochondria: A potent stroke therapeutic target. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014;20:275–81. doi: 10.1111/cns.12208. doi: 10.1111/cns.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin CH, Lee HT, Lee SD, Lee W, Cho CW, Lin SZ, et al. Role of HIF-1a-activated Epac1 on HSC-mediated neuroplasticity in stroke model. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;58:76–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.05.006. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi BR, Kim DH, Back DB, Kang CH, Moon WJ, Han JS, et al. Characterization of white matter injury in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Stroke. 2016;47:542–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011679. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.115.011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fowler JH, McQueen J, Holland PR, Manso Y, Marangoni M, Scott F, et al. Dimethyl fumarate improves white matter function following severe hypoperfusion: Involvement of microglia/macrophages and inflammatory mediators. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0271678X17713105. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1177/0271678x17713105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyamoto N, Pham LD, Hayakawa K, Matsuzaki T, Seo JH, Magnain C, et al. Age-related decline in oligodendrogenesis retards white matter repair in mice. Stroke. 2013;44:2573–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001530. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.113.001530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu X, Yu SP, Fraser JL, Lu Z, Ogle ME, Wang JA, et al. Transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells improves infarcted heart function via enhanced survival of implanted cells and angiogenesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.071. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shao G, Lu GW. Hypoxic preconditioning in an autohypoxic animal model. Neurosci Bull. 2012;28:316–20. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1222-x. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shi X, Zhang Y, Zheng J, Pan J. Reactive oxygen species in cancer stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:1215–28. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4529. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng J, Li W, Kang B, Zhou Y, Song J, Dan S, et al. Tryptophan derivatives regulate the transcription of Oct4 in stem-like cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7209. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8209. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar SM, Liu S, Lu H, Zhang H, Zhang PJ, Gimotty PA, et al. Acquired cancer stem cell phenotypes through Oct4-mediated dedifferentiation. Oncogene. 2012;31:4898–911. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.656. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li QJ, Cai JQ, Liu CY. Evolving molecular genetics of glioblastoma. Chin Med J. 2016;129:464–71. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.176065. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.176065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Su HT, Weng CC, Hsiao PJ, Chen LH, Kuo TL, Chen YW, et al. Stem cell marker nestin is critical for TGF-ß1-mediated tumor progression in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:768–79. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0511. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.mcr-12-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas S, Harding MA, Smith SC, Overdevest JB, Nitz MD, Frierson HF, et al. CD24 is an effector of HIF-1-driven primary tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5600–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3666. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-11-3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Proulx-Bonneau S, Guezguez A, Annabi B. A concerted HIF-1a/MT1-MMP signalling axis regulates the expression of the 3BP2 adaptor protein in hypoxic mesenchymal stromal cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pistollato F, Rampazzo E, Persano L, Abbadi S, Frasson C, Denaro L, et al. Interaction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a and Notch signaling regulates medulloblastoma precursor proliferation and fate. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1918–29. doi: 10.1002/stem.518. doi: 10.1002/stem.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu S, Kumar SM, Martin JS, Yang R, Xu X. Snail1 mediates hypoxia-induced melanoma progression. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:3020–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.038. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Carolis S, Bertoni S, Nati M, D’Anello L, Papi A, Tesei A, et al. Carbonic anhydrase 9 mRNA/microRNA34a interplay in hypoxic human mammospheres. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231:1534–41. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25245. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang BC, Ma J. Role of MicroRNAs in malignant glioma. Chin Med J. 2015;128:1238–44. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.156141. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.156141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou B, Damrauer JS, Bailey ST, Hadzic T, Jeong Y, Clark K, et al. Erythropoietin promotes breast tumorigenesis through tumor-initiating cell self-renewal. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:553–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI69804. doi: 10.1172/jci69804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu Y, Sattarzadeh A, Diepstra A, Visser L, van den Berg A. The microenvironment in classical Hodgkin lymphoma: An actively shaped and essential tumor component. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;24:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.07.002. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen D, Song M, Mohamad O, Yu SP. Inhibition of Na+/K+-ATPase induces hybrid cell death and enhanced sensitivity to chemotherapy in human glioblastoma cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:716. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-716. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Song M, Chen D, Yu SP. The TRPC channel blocker SKF 96365 inhibits glioblastoma cell growth by enhancing reverse mode of the Na(+)/Ca(2+) exchanger and increasing intracellular Ca(2+) Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:3432–47. doi: 10.1111/bph.12691. doi: 10.1111/bph.12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pistollato F, Chen HL, Rood BR, Zhang HZ, D’Avella D, Denaro L, et al. Hypoxia and HIF1alpha repress the differentiative effects of BMPs in high-grade glioma. Stem Cells. 2009;27:7–17. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0402. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aprelikova O, Pandolfi S, Tackett S, Ferreira M, Salnikow K, Ward Y, et al. Melanoma antigen-11 inhibits the hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase 2 and activates hypoxic response. Cancer Res. 2009;69:616–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0811. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-0811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gu Y, Zhang M, Li GH, Gao JZ, Guo L, Qiao XJ, et al. Diagnostic values of vascular endothelial growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor for benign and malignant hydrothorax. Chin Med J. 2015;128:305–9. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.150091. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.150091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ding JB, Chen JR, Xu HZ, Qin ZY. Effect of hyperbaric oxygen on the growth of intracranial glioma in rats. Chin Med J. 2015;128:3197–203. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.170278. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.170278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee SP, Youn SW, Cho HJ, Li L, Kim TY, Yook HS, et al. Integrin-linked kinase, a hypoxia-responsive molecule, controls postnatal vasculogenesis by recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to ischemic tissue. Circulation. 2006;114:150–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595918. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.595918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rossant J. Stem cells and early lineage development. Cell. 2008;132:527–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.039. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang KH, Li M. Clonal isolation of an intermediate pluripotent stem cell state. Stem Cells. 2013;31:918–27. doi: 10.1002/stem.1330. doi: 10.1002/stem.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.De Los Angeles A, Ferrari F, Xi R, Fujiwara Y, Benvenisty N, Deng H, et al. Hallmarks of pluripotency. Nature. 2015;525:469–78. doi: 10.1038/nature15515. doi: 10.1038/nature15515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Dynamic pluripotent stem cell states and their applications. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17:509–25. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.10.009. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wei ZZ, Yu SP, Lee JH, Chen D, Taylor TM, Deveau TC, et al. Regulatory role of the JNK-STAT1/3 signaling in neuronal differentiation of cultured mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2014;34:881–93. doi: 10.1007/s10571-014-0067-4. doi: 10.1007/s10571-014-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cui L, Jiang J, Wei L, Zhou X, Fraser JL, Snider BJ, et al. Transplantation of embryonic stem cells improves nerve repair and functional recovery after severe sciatic nerve axotomy in rats. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1356–65. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0333. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Takashima Y, Guo G, Loos R, Nichols J, Ficz G, Krueger F, et al. Resetting transcription factor control circuitry toward ground-state pluripotency in human. Cell. 2014;158:1254–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Theunissen TW, Powell BE, Wang H, Mitalipova M, Faddah DA, Reddy J, et al. Systematic identification of culture conditions for induction and maintenance of naive human pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:471–87. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.002. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ware CB, Nelson AM, Mecham B, Hesson J, Zhou W, Jonlin EC, et al. Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:4484–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319738111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319738111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Duggal G, Warrier S, Ghimire S, Broekaert D, Van der Jeught M, Lierman S, et al. Alternative routes to induce naïve pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2686–98. doi: 10.1002/stem.2071. doi: 10.1002/stem.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pastor WA, Chen D, Liu W, Kim R, Sahakyan A, Lukianchikov A, et al. Naive human pluripotent cells feature a methylation landscape devoid of blastocyst or germline memory. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.019. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ma L, Hu B, Liu Y, Vermilyea SC, Liu H, Gao L, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived GABA neurons correct locomotion deficits in quinolinic acid-lesioned mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:455–64. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.021. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu Y, Weick JP, Liu H, Krencik R, Zhang X, Ma L, et al. Medial ganglionic eminence-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells correct learning and memory deficits. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:440–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2565. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nilbratt M, Porras O, Marutle A, Hovatta O, Nordberg A. Neurotrophic factors promote cholinergic differentiation in human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1476–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00916.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bissonnette CJ, Lyass L, Bhattacharyya BJ, Belmadani A, Miller RJ, Kessler JA. The controlled generation of functional basal forebrain cholinergic neurons from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:802–11. doi: 10.1002/stem.626. doi: 10.1002/stem.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Patani R, Hollins AJ, Wishart TM, Puddifoot CA, Alvarez S, de Lera AR, et al. Retinoid-independent motor neurogenesis from human embryonic stem cells reveals a medial columnar ground state. Nat Commun. 2011;2:214. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1216. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lu J, Zhong X, Liu H, Hao L, Huang CT, Sherafat MA, et al. Generation of serotonin neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:89–94. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3435. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goldman SA, Kuypers NJ. How to make an oligodendrocyte. Development. 2015;142:3983–95. doi: 10.1242/dev.126409. doi: 10.1242/dev.126409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Benraiss A, Goldman SA. Cellular therapy and induced neuronal replacement for Huntington's disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:577–90. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0075-8. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0075-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Barker RA, Mason SL, Harrower TP, Swain RA, Ho AK, Sahakian BJ, et al. The long-term safety and efficacy of bilateral transplantation of human fetal striatal tissue in patients with mild to moderate Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84:657–65. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302441. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang S, Bates J, Li X, Schanz S, Chandler-Militello D, Levine C, et al. Human iPSC-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells can myelinate and rescue a mouse model of congenital hypomyelination. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:252–64. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.002. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barker RA, Drouin-Ouellet J, Parmar M. Cell-based therapies for Parkinson disease-past insights and future potential. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:492–503. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.123. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]