Abstract

Objectives

Blacks and Hispanics are at increased risk for dementia, even after socioeconomic and vascular factors are taken into account. This study tests a comprehensive model of psychosocial pathways leading to differences in longitudinal cognitive outcomes among older blacks and Hispanics, compared to non-Hispanic whites.

Methods

Using data from 10,173 participants aged 65 and older in the Health and Retirement Study, structural equation models tested associations among race/ethnicity, perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, external locus of control, and 6-year memory trajectories, controlling for age, sex, educational attainment, income, wealth, and chronic diseases.

Results

Greater perceived discrimination among blacks was associated with lower initial memory level via depressive symptoms and external locus of control, and with faster memory decline directly. Greater depressive symptoms and external locus of control among Hispanics were each independently associated with lower initial memory, but there were no pathways from Hispanic ethnicity to memory decline.

Discussion

Depression and external locus of control partially mediate racial/ethnic differences in memory trajectories. Perceived discrimination is a major driver of these psychosocial pathways for blacks, but not Hispanics. These results can inform the development of policies and interventions to reduce cognitive morbidity among racially/ethnically diverse older adults.

Keywords: Cognition, Depression, Longitudinal Change, Minority and Diverse Populations

Racial/ethnic inequalities in dementia incidence exist, but mechanisms underlying these disparities are not well understood (Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2016; Tang et al., 2001). Importantly, incident dementia disparities persist despite statistical control for education, illiteracy, stroke history, hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes (Tang et al., 2001). Further, genetic risk factors play a smaller role in conferring risk of both memory decline and dementia incidence among racial/ethnic minorities, as compared to non-Hispanic whites (Marden et al., 2016; Tang et al., 1998). One explanation for persistent disparities despite consideration of these socioeconomic, educational, physical health, and genetic variables is that there are other causes of inequalities that are not captured by these constructs.

A growing body of research suggests that psychosocial experiences may contribute to racial/ethnic inequalities in episodic memory, a primary determinant of dementia risk. For example, daily experiences of discrimination are associated with lower episodic memory performance among blacks (Barnes et al., 2012; Thames et al., 2013). In the Survey of Midlife in the United States, external locus of control, or the belief that life outcomes are disproportionately influenced by outside forces, partially mediates black–white differences in episodic memory and executive functioning (Zahodne, Manly, Smith, Seeman, & Lachman, 2017). An important limitation of these studies is that they are cross-sectional, so it is not possible to separately determine how psychosocial factors influence memory level versus rate of memory change. Cognitive performance at a single point in time reflects a confluence of circumstances that have accumulated throughout the life course (e.g., IQ, educational, and occupational experiences), as well as transient perturbations in cognitive performance and measurement error. In contrast, rate of late-life cognitive change is more likely to reflect processes of aging and age-related disease. Therefore, examining the influence of psychosocial factors on both initial memory level and rate of memory change in a longitudinal framework is critical for advancing knowledge about the role of psychosocial factors in cognitive aging and dementia inequalities (Manly & Mungas, 2015).

Another limitation of existing studies is that they have not tested specific theories about how correlated psychosocial variables influence one another and lead to cognitive impairment. For example, Barnes et al. (2012) found that the association between perceived discrimination and episodic memory performance among blacks was attenuated upon controlling for depressive symptoms, but the authors did not formally test whether depressive symptoms mediated the effect of perceived discrimination on memory performance. Similarly, Zahodne et al. (2017) found that external locus of control was associated with blacks’ lower episodic memory performance independent of perceived discrimination, but the authors did not model the relationship between perceived discrimination and external locus of control to examine potential indirect effects. Thus, the specific roles of these related constructs (i.e., perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and external locus of control) in explaining memory inequalities remains unclear. Finally, the vast majority of studies on psychosocial influences on cognitive disparities have focused on black–white differences despite the fact that Hispanics are also at increased risk of incident dementia (Tang et al., 2001) and are a large and rapidly-growing segment of the U.S. older adult population. While perceived discrimination has been linked to poorer educational, employment, and mental health outcomes among Hispanics (Lee & Ahn, 2012), its relationship to late-life cognition has not yet been established.

The current study tests a comprehensive model of psychosocial pathways leading to poorer longitudinal memory outcomes among older blacks and Hispanics. Based on previous theoretical work on inequity, racism, and locus of control (Lefcourt, 2014; Mirowsky & Ross, 2007; Ross & Mirowsky, 2013), we propose that the discrimination experienced by racial/ethnic minorities can result in both depressive symptoms and a reduced sense of control over life outcomes. These negative psychological consequences of discrimination more proximally influence cognitive performance. In the current study, we tested this model in a longitudinal structural equation modeling framework using six years of data from the Health and Retirement Study.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative sample of Americans aged 50 and older that has been ongoing since 1992 (Sonnega et al., 2014). Details of the HRS longitudinal panel design, sampling, and all questionnaires are available on the HRS website (http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu). Participants in HRS are interviewed in English or Spanish every 2 years. Inclusion criteria for the current study were: (a) age 65 and older at the time of the 2006 assessment wave, (b) available data on the outcome of interest (memory; see below), and (c) self-reported race/ethnicity of non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, or Hispanic (of any race). The 2006 assessment wave was chosen as the baseline occasion because this was the first time the complete psychosocial leave-behind questionnaire, which included measures of perceived discrimination and locus of control, was administered. Characteristics of the 10,173 HRS participants included in the current study are shown in Table 1. All participants provided written informed consent, and all study procedures were approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline, Expressed as Mean (Standard Deviation) Unless Otherwise Specified

| Whole sample N = 10,173 | White N = 8,067 | Black N = 1,313 | Hispanic N = 793 | Significant group differences† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (65–104) | 74.5 (7.3) | 74.8 (7.3) | 73.5 (7.2) | 73.0 (7.0) | H=B<W |

| Gender (% women) | 58.0 | 56.8 | 64.4 | 60.0 | W<H<B |

| Education (0–17) | 12.1 (3.3) | 12.7 (2.7) | 10.8 (3.5) | 8.1 (4.5) | H<B<W |

| Income (thousands) | 48.5 (106.7) | 54.2 (118.0) | 28.0 (30.9) | 24.3 (34.8) | H=B<W |

| Wealth (thousands) | 530.1 (1357.7) | 630.0 (1498.1) | 134.9 (379.9) | 168.5 (295.4) | B=H<W |

| Chronic disease burden (0–6) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) | 1.9 (1.2) | H<W<B |

| Stroke (% yes) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 11.9 | 5.7 | H<W=B |

| Perceived discrimination (6–30) | 8.8 (3.3) | 8.7 (3.2) | 9.5 (3.9) | 8.7 (3.9) | W=H<B |

| Depressive symptoms (0–8) | 1.5 (1.9) | 1.4 (1.8) | 1.8 (2.0) | 2.1 (2.3) | W<B<H |

| External locus of control (1–6) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.3) | W<B<H |

| Immediate recall (0–10) | 5.0 (1.7) | 5.2 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.3 (1.7) | H=B<W |

| Delayed recall (0–10) | 3.9 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.0) | 3.0 (2.0) | 3.3 (1.8) | B<H<W |

Note. B = Black; H = Hispanic; W = White.

†Comparisons based on analyses of variance with Bonferronni-corrected post hoc tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables with p < .05.

Measures

Memory

Cognitive functioning was assessed over the phone with measures of episodic memory and global mental status. Episodic memory was chosen as the outcome in this study because (a) it is highly sensitive to age-related cognitive decline and early dementia (Bäckman, Small, & Fratiglioni, 2001) and (b) previous work on discrimination and cognitive aging has focused on episodic memory (Barnes et al., 2012; Thames et al., 2013; Zahodne et al., 2017). For the memory task, participants hear a list of 10 words that they are asked to recall immediately and following a 5-min delay. In the current study, scores on the immediate and delayed recall trials were combined into a z-score composite based on means/SDs from the baseline (2006) assessment to improve reliability. Secondary analyses examined immediate and delayed recall scores individually.

Discrimination

Perceived discrimination was assessed by a leave-behind questionnaire with five items querying experiences of discrimination in “day-to-day life” (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Items included, “You are treated with less courtesy or respect than other people,” “You receive poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores,” “People act as if they think you are not smart,” “People act as if they are afraid of you,” and “You are threatened or harassed.” Items are rated for frequency on a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = Almost every day to 6 = Never). In the current study, sum scores were reversed prior to analysis so that higher scores correspond to greater perceived discrimination.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms over the past week were assessed as part of the core HRS telephone interview with eight items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) modified for a yes/no format. Higher scores correspond to more depressive symptoms.

External locus of control

External locus of control was assessed by a leave-behind questionnaire with five items querying perceived constraints (Lachman & Weaver, 1998). Items included, “I often feel helpless in dealing with the problems of life,” “Other people determine most of what I can and cannot do,” “What happens in my life is often beyond my control,” “I have little control over the things that happen to me,” and “There is really no way I can solve the problems I have.” Items are rated for agreement on a six-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 6 = Strongly agree). Total scores represent the average score across items, and higher scores correspond to more external locus of control.

Race/ethnicity

Race was queried with the question, “What race do you consider yourself to be: white, black or African American, American Indian, Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or something else?” Ethnicity was queried with the question, “Do you consider yourself Hispanic or Latino?” In the current study, the three categories of non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic were dummy-coded with non-Hispanic white as the reference group and included together in a single model.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics were computed in SPSS. Analyses of variance with post hoc Bonferroni tests were used to compare racial/ethnic groups. Memory trajectories from 2006 to 2012 were modeled using latent growth curve analysis with maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus. Time was parameterized as years from the 2006 assessment wave, and all analyses controlled for age at baseline (2006 assessment wave). In the current sample, participants had an average of 3.2 time points of data (range: 1–4) between 2006 and 2012. Missing data were managed with full information maximum likelihood using all available data at each occasion. Latent variables corresponded to initial memory (intercept) and rate of change in memory over the 6-year follow-up (linear slope).

Primary analyses controlled for age, gender, education, income, wealth, chronic disease burden, and history of stroke. Age was age at the time of the 2006 wave (in years). Gender was a dichotomous variable with male as the reference category. Education was self-reported years of education. Income was total household income from all queried sources (e.g., respondent and spouse earnings, pensions, social security) for the last calendar year at the time of the 2006 wave. Wealth was the net value of total wealth (including second home) at the time of the 2006 wave and was calculated as the sum of assets (e.g., real estate, vehicles, bank accounts, stocks) minus debts (e.g., mortgages, other loans) from all queried sources. Chronic disease burden was the sum of the self-reported presence/absence of the following six chronic diseases at the time of the 2006 wave: hypertension, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart problems, and arthritis. Stroke was a dichotomous variable with absence of self-reported stroke as the reference category.

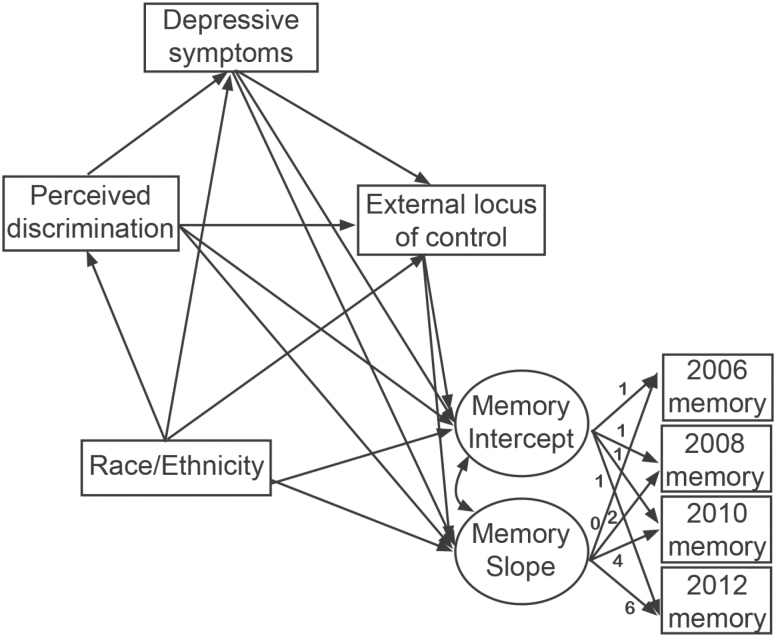

Structural equation modeling was used to estimate direct and indirect effects of race/ethnicity on memory trajectories through the psychosocial variables of interest: perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and external locus of control in a single model. Direct effects reflect associations between race/ethnicity and memory that are independent of perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, external locus of control, and all covariates. Indirect effects reflect the product of all regression coefficients within a given pathway from race/ethnicity to memory (through perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and/or external locus of control), independent of all covariates. As depicted in Figure 1, intercept and slope were regressed onto all predictors of interest and covariates. In addition, external locus of control was regressed onto depressive symptoms, perceived discrimination, and race/ethnicity. Depressive symptoms were regressed onto perceived discrimination and race/ethnicity, and perceived discrimination was regressed onto race/ethnicity. Additional models were run to evaluate the relative fit of all alternative ways of ordering the psychosocial variables. Model fit was evaluated with the following commonly-used indices: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean square residual (SRMR). CFI > 0.95, TLI > 0.95, RMSEA < 0.06, and SRMR < 0.05 were used as criteria for adequate model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 1.

Schematic of all paths estimated by the structural equation model. For simplicity, covariates (i.e., age, gender, education, income, wealth, chronic disease burden, and stroke) are not shown.

Results

Racial/Ethnic Group Differences in Study Variables

As shown in Table 1, there were significant racial/ethnic differences in all study variables. Specifically, whites were older and less likely to be women, reported more education, income, and wealth, reported fewer depressive symptoms and less external locus of control, and recalled more words immediately and following the delay than both non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics. Whites reported fewer chronic diseases and less perceived discrimination than blacks, but more chronic diseases and strokes than Hispanics. Compared to Hispanics, blacks reported more education, more chronic diseases, more strokes, fewer depressive symptoms, more perceived discrimination, and less external locus of control. Blacks and Hispanics performed similarly on immediate recall, but Hispanics recalled more words than blacks following the delay.

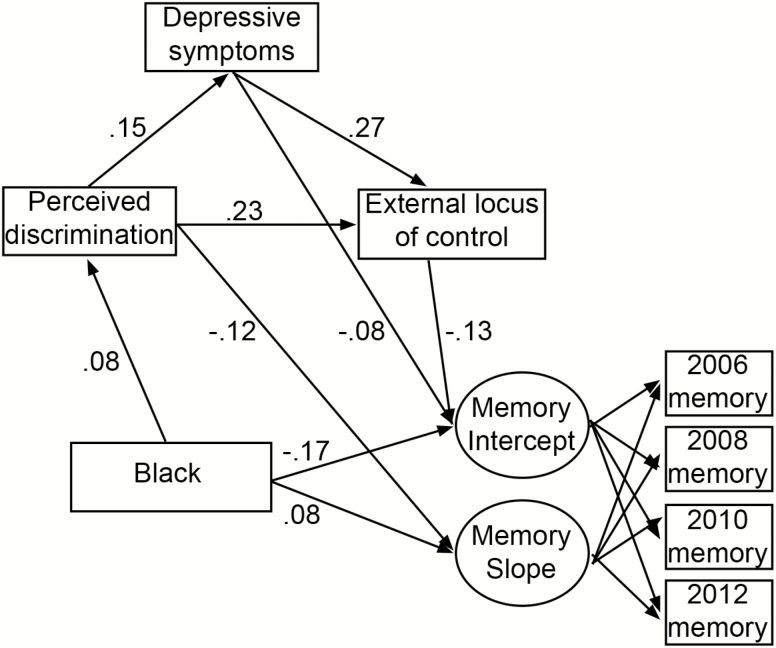

Initial Memory

The model depicted in Figure 1 fit very well: CFI = 0.984; TLI = 0.970; RMSEA = 0.026 (90% CI: 0.023–0.028), SRMR = 0.020. As shown in Table 2, there were significant direct and indirect effects of black race and Hispanic ethnicity on initial memory performance (intercept). As depicted in Figure 2, there were no significant single-mediator pathways from black race to initial memory performance. Rather, all significant indirect effects of black race on initial memory performance started with higher perceived discrimination (standardized estimate = 0.085; SE = 0.016; p < .001). Higher perceived discrimination predicted greater depressive symptoms (standardized estimate = 0.149; SE = 0.014; p < .001), and in turn, greater depressive symptoms predicted lower initial memory performance (standardized estimate = −0.081; SE = 0.012; p < .001). Independent of this path, higher perceived discrimination also predicted greater external locus of control (standardized estimate = 0.228; SE = 0.014; p < .001), and in turn, greater external locus of control predicted lower initial memory performance (standardized estimate = −0.132; SE = 0.018; p < .001). Thus, greater perceived discrimination among blacks led to worse initial memory performance via two independent pathways: through increased depressive symptoms and through increased external locus of control.

Table 2.

Standardized Direct and Indirect Effects of Race/Ethnicity Estimated Within a Single Model

| Non-Hispanic black race | Hispanic ethnicity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial memory level | Rate of memory change | Initial memory level | Rate of memory change | |||||

| Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | Estimate (SE) | p | |

| Direct effect | −0.171 (0.011) | <.001 | 0.084 (0.037) | .021 | −0.039 (0.011) | .001 | 0.072 (0.038) | .056 |

| Specific indirect effects | ||||||||

| Perceived discrimination | 0.003 (0.002) | .053 | −0.010 (0.005) | .048 | 0.000 (0.001) | .987 | 0.000 (0.002) | .987 |

| Depressive symptoms | −0.001 (0.001) | .275 | 0.000 (0.000) | .768 | −0.003 (0.001) | .001 | 0.000 (0.002) | .760 |

| External locus of control | 0.003 (0.002) | .138 | −0.002 (0.002) | .275 | −0.004 (0.002) | .042 | 0.003 (0.002) | .203 |

| Perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms | −0.001 (0.000) | <.001 | 0.000 (0.001) | .760 | 0.000 (0.000) | .987 | 0.000 (0.000) | .987 |

| Depressive symptoms, external locus of control | 0.000 (0.000) | .274 | 0.000 (0.000) | .366 | −0.001 (0.000) | .001 | 0.001 (0.001) | .146 |

| Perceived discrimination, external locus of control | −0.003 (0.001) | <.001 | 0.002 (0.001) | .132 | 0.000 (0.000) | .987 | 0.000 (0.000) | .987 |

| Perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, external locus of control | −0.000 (0.000) | <.001 | 0.000 (0.000) | .136 | 0.000 (0.000) | .987 | 0.000 (0.000) | .987 |

Note. SE = standard error.

Figure 2.

Significant pathways from black race to memory trajectories, estimated within the same model that included Hispanic ethnicity. Numbers represent standardized regression coefficients. For simplicity, non-significant paths (see Figure 1) and covariates (i.e., age, gender, education, income, wealth, chronic disease burden, stroke) are not shown.

In addition to these independent two-mediator paths, there was a third significant indirect effect of black race through all three variables. Specifically, black race was associated with more perceived discrimination (standardized estimate = 0.085; SE = 0.016; p < .001), which predicted greater depressive symptoms (standardized estimate = 0.149; SE = 0.014; p < .001), which predicted greater external locus of control (standardized estimate = 0.266; SE = 0.014; p < .001), which predicted lower initial memory performance (standardized estimate = −0.132; SE = 0.018; p < .001). Thus, depressive symptoms related to perceived discrimination were associated with lower initial memory performance directly, as well as indirectly through external locus of control.

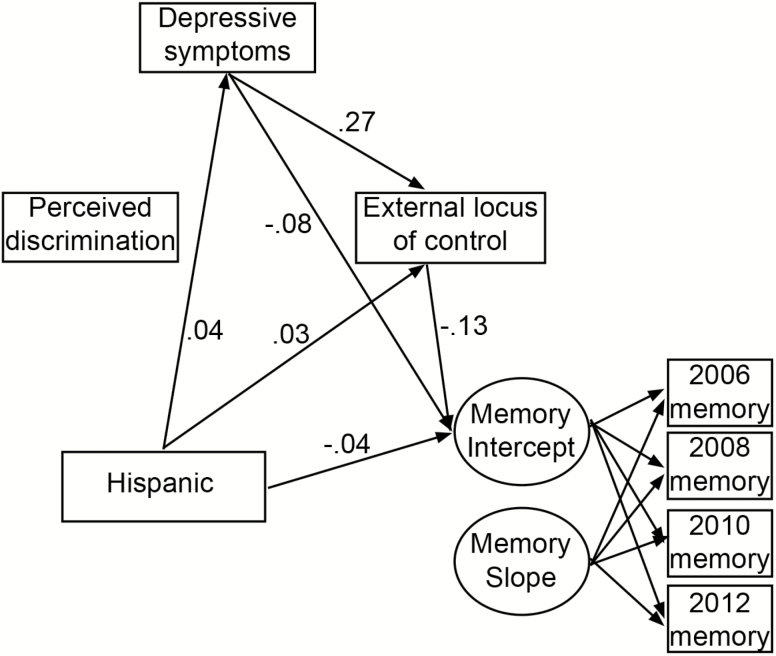

As depicted in Figure 3 and in contrast to black race, Hispanic ethnicity was not associated with perceived discrimination (standardized estimate = 0.000; SE = 0.016; p = .987). There were significant indirect effects of Hispanic ethnicity on initial memory performance through depressive symptoms and external locus of control. Specifically, Hispanic ethnicity was associated with greater depressive symptoms (standardized estimate = 0.040; SE = .010; p < .001), and in turn, greater depressive symptoms predicted lower initial memory performance (standardized estimate = −0.081; SE = .012; p < .001). Independent of this path, Hispanic ethnicity was also associated with greater external locus of control (standardized estimate = 0.032; SE = .015; p = .035), and in turn, greater external locus of control predicted lower initial memory performance (standardized estimate = −0.132; SE = 0.018; p < .001).

Figure 3.

Significant pathways from Hispanic ethnicity to memory trajectories, estimated within the same model that included black race. Numbers represent standardized regression coefficients. For simplicity, non-significant paths (see Figure 1) and covariates (i.e., age, gender, education, income, wealth, chronic disease burden, stroke) are not shown.

In addition to these independent, single-mediator paths through depressive symptoms and external locus of control, there was a third significant indirect effect of Hispanic ethnicity through both variables, such that Hispanic ethnicity was associated with more depressive symptoms (standardized estimate = 0.040; SE = 0.010; p < .001), which predicted greater external locus of control (standardized estimate = 0.266; SE = 0.014; p < .001), which predicted lower initial memory performance (standardized estimate = −0.132; SE = 0.018; p < .001).

Rate of Memory Change

As shown in Table 2, there were significant direct and indirect effects of black race, but not Hispanic ethnicity, on rate of memory change (linear slope). The only significant indirect effect of black race on memory change was through perceived discrimination. Specifically, black race was associated with greater perceived discrimination (standardized estimate = 0.085; SE = 0.016; p < .001), and greater perceived discrimination predicted faster memory decline (standardized estimate = −0.119; SE = 0.056; p = .033). Independent of perceived discrimination, black race was associated with slower memory decline (standardized estimate = 0.084; SE = 0.037; p = .021). Neither depressive symptoms (standardized estimate = −0.013; SE = 0.041; p = .760) nor external locus of control (standardized estimate = 0.094; SE = 0.060; p = .115) was independently associated with memory decline.

Alternative Model Specifications

In order to explore the possibility that the a priori ordering of the psychosocial variables did not best represent the data, we ran five additional models varying the direction of associations among the three psychosocial variables. We then compared the fit of these models to that of the model depicted in Figure 1. Because the only difference between these models was the ordering of the psychosocial variables, degrees of freedom did not differ across models. As shown in Supplementary Table 1, fit of each alternative model was poorer than that of the a priori model, which was evident across all fit indices.

Immediate Versus Delayed Recall

The best-fitting model described above for memory composite scores was re-run separately for immediate recall and delayed recall scores. Direct and indirect effects of black race or Hispanic ethnicity on lower initial memory performance were virtually identical across models of memory composite scores, immediate memory, and delayed memory.

With regard to rate of memory change, a significant direct effect of black race was only found in memory composite (see Table 2) and immediate recall (standardized estimate = 0.111; SE = 0.038; p = .003) models. A significant direct effect of Hispanic ethnicity on rate of memory change was only found in the immediate recall model (standardized estimate = 0.084; SE = 0.038; p = .029). There were no significant indirect effects of Hispanic ethnicity on rates of memory change across the three models. The indirect effect of black race on rate of memory change through perceived discrimination was only significant for memory composite scores (see Table 2) and immediate recall scores (standardized estimate = −0.013; SE = 0.005; p = .015). There was no significant indirect effect of black race on rate of delayed recall change through perceived discrimination (standardized estimate = −0.006; SE = 0.006; p = .294) because perceived discrimination was not independently associated with changes in delayed recall (standardized estimate = −0.073; SE = 0.068; p = .284).

Discussion

The results of this longitudinal study suggest that psychosocial factors (i.e., perceived discrimination, depressive symptoms, and external locus of control) contribute to racial/ethnic inequalities in late-life memory trajectories. For blacks, perceived discrimination not only initiates a cascade of psychological repercussions that culminates in lower memory level, but it also directly predicts faster memory decline. For Hispanics, the primary contributors to the psychological sequelae of depressive symptoms and external locus of control remain unclear, but these factors similarly lead to lower initial memory in this group.

In the current study, blacks reported more perceived discrimination than whites. Further, these discrimination experiences were central to black–white differences in memory trajectories. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that perceived discrimination is associated with lower episodic memory performance among blacks (Barnes et al., 2012; Thames et al., 2013). This study extends these previous findings by including whites to demonstrate that perceived discrimination mediates black–white differences in memory trajectories, and by delineating multiple psychological pathways from discrimination to lower cognitive performance through depressive symptoms and/or external locus of control. This study also extends previous cross-sectional work by modeling longitudinal changes in cognitive performance, thereby providing stronger evidence that perceived discrimination negatively influences processes of aging and disease. Potential physiological mechanisms underlying the negative effects of perceived discrimination on memory trajectories include increased C-reactive protein (Lewis, Aiello, Leurgans, Kelly, & Barnes, 2010), increased hypertension (Lewis et al., 2009), and increased atherosclerotic disease (Lewis et al., 2006). Further, a growing body of animal research supports the view that chronic social stress, which is reflected in the measure of perceived discrimination, causes pathologic changes in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Chen, Huang, & Hsu, 2015; Stankiewicz, Goscik, Majewska, Swiergiel, & Juszczak, 2015; Wu et al., 2014). The current finding that the negative effect of perceived discrimination on memory decline was driven by the immediate recall trial of a word list task hints that cognitive processes such as learning and working memory, which are heavily dependent on the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, may be particularly vulnerable to perceived discrimination.

Of note, there were no significant associations between black race and depressive symptoms or external locus of control independent of perceived discrimination, which is consistent with previous studies showing that blacks have lower rates of mental disorders and higher rates of flourishing than whites (Keyes, 2009). Independent of perceived discrimination, black race was associated with slower episodic memory decline, which has previously been reported for other cognitive domains and may reflect higher mortality selection among black older adults (Wilson, Capuano, Sytsma, Bennett, & Barnes, 2015). Models examining memory trajectories separately for immediate and delayed recall scores suggested that this mortality selection effect may be particularly evident for immediate recall, as opposed to delayed recall.

The finding that Hispanics did not report more perceived discrimination than whites in the current study is consistent with previous work that also used items from the Everyday Discrimination Scale (Lewis, Yang, Jacobs, & Fitchett, 2012). These convergent findings may relate to the item content of this scale. While items are worded to be broadly applicable to discrimination experiences related to many different identities (e.g., ethnicity, gender, age), they were developed based on qualitative interviews with black women (Essed, 1990). Therefore, the scale may better capture core aspects of discrimination experienced by blacks, compared with Hispanics. Levels of discrimination reported by Hispanics can also be moderated by cultural and immigrant variables. For example, lower levels of acculturation (i.e., less time in the United States, lower English proficiency), older age of immigration, and higher ethnic identity have all been associated with lower rates of perceived discrimination among Hispanics in the United States (Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000; Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegria, 2008).

Hispanics in this study reported more depressive symptoms and external locus of control than whites. These findings are likely influenced by multiple sociocultural and immigrant factors. For example, while greater acculturation is negatively associated with external locus of control among Hispanics, longer exposure to U.S. culture is positively associated with depression (Roncancio, Ward, & Berenson, 2011; Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2014). Higher rates of depression among Hispanics in the United States have also been linked to lower rates of antidepressant use, which is due, in part, to lower access to insurance (Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2014). It has also been suggested that the cultural construct of fatalismo, or the general belief that life events are beyond one’s control due to fate, destiny or a higher power, contributes to higher levels of depressive symptoms and external locus of control among Hispanics (Anastasia & Bridges, 2015). However, fatalismo has also been found to facilitate coping in the face of health concerns (Keeley, Wright, & Condit, 2009). Future studies should endeavor to identify cultural (e.g., fatalismo), interpersonal (e.g., ethnic discrimination), and/or social structural (e.g., limited employment opportunities) experiences that drive Hispanic–white disparities in psychological and cognitive outcomes. Of note, Hispanic ethnicity was not associated with rate of memory change, which is consistent with previous studies suggesting that the effects of ethnicity on rate of cognitive changes are negligible in relation to its effects on cognitive level (Gross et al., 2015).

For both blacks and Hispanics, lower initial memory performance was most proximally associated with depressive symptoms and external locus of control. The nature of the link between depressive symptoms and lower episodic memory has been a subject of long-standing and active debate. One possibility is that depressive symptoms are negatively associated with health-promoting behaviors, such as physical activity and a healthy diet (Williams, Plassman, Burke, Holsinger, & Benjamin, 2010). Another possibility is that depressive symptoms are directly linked to vascular or other types of pathology that causes cognitive symptoms. While the current study controlled for self-reported stroke and chronic disease burden, depressive symptoms may indicate the presence of subclinical vascular disease (e.g., reduced cerebral blood flow, white matter disconnection), which can compromise episodic memory (Taylor, Aizenstein, & Alexopoulos, 2013). A third possibility is that chronic elevations in stress in the context of depressive symptoms cause hippocampal damage through a glucocorticoid cascade (Sapolsky, 2001).

While associations between control beliefs and cognitive performance have been established through cross-sectional (Agrigoroaei & Lachman, 2011), longitudinal (Seeman, McAvay, Merrill, Albert, & et al, 1996), and intervention (Rodin, 1983) studies, mechanisms underlying this link have been less extensively studied. Similar to depressive symptoms, external locus of control may reduce health-promoting behaviors (Lachman, Neupert, & Agrigoroaei, 2011). It may also reduce participation in cognitively challenging activities that could enrich cognitive capacity (Bandura, 1981, 1988, 1989). Even if an individual is interested in these beneficial activities, the same societal and institutional forces that promote external locus of control may also limit access to activities and resources. In the short-term, greater external locus of control may interfere with performance by heightening anxiety, cognitive rumination, and/or self-doubt (Bandura & Wood, 1989; Wood & Bandura, 1989). External locus of control has also been associated with suboptimal memory recall strategies (Starnes & Loeb, 1993). Importantly, the finding that depressive symptoms and external locus of control exert independent influences on episodic memory indicates that the association between control beliefs and cognition is not entirely explained by depression, nor vice versa.

Residual direct effects of both black race and Hispanic ethnicity on initial memory in the current study indicate that the socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial variables examined were not sufficient to fully explain racial/ethnic differences. Therefore, additional work is needed to more thoroughly delineate mechanisms of cognitive inequalities. For example, systematic differences in educational quality (Manly, Jacobs, Touradji, Small, & Stern, 2002) and neighborhood characteristics (Rosso et al., 2016) across racial/ethnic groups have also been implicated in cognitive disparities. Another future direction is to incorporate measures of religiosity, which differs across racial/ethnic groups, has been associated with better psychological and cognitive outcomes, and may therefore represent a potential protective factor for some racial/ethnic groups (Inzelberg et al., 2013; Prado et al., 2004). To this end, it may be useful to differentiate between intrinsic, organizational, and non-organizational religiosity, as well as to explore how certain cultural constructs (e.g., fatalismo) might overlap with religiosity. Future studies should also examine Hispanic subgroups, which could not reliably be done in the current study due to sample size. Limitations of this study and other large-scale, national studies include the use of a telephone-administered cognitive test and self-reported health. Therefore, future studies are needed to determine whether these results are similar when face-to-face cognitive testing and objective health measures are employed.

Strengths of this study include the use of longitudinal data in a large, nationally representative sample of older adults, the inclusion of a comprehensive set of socioeconomic covariates, and the use of structural equation modeling to explicitly test comprehensive and alternative models based on theory. Another strength is the focus on both blacks and Hispanics, given that research on Hispanic cognitive aging is relatively underdeveloped despite the rapidly growing population of Hispanic older adults in the United States.

In conclusion, perceived discrimination is a major driver of black–white inequalities in late-life memory trajectories. For both blacks and Hispanics, the psychological factors of depression and external locus of control are most proximally associated with lower memory level. These results can inform the development of policies and interventions to reduce cognitive morbidity among racially/ethnically diverse older adults.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes on Aging (grant numbers NIA R00AG047963 and R01AG054520). The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agrigoroaei S., & Lachman M. E (2011). Cognitive functioning in midlife and old age: Combined effects of psychosocial and behavioral factors. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(Suppl. 1), i130–40. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasia E. A., & Bridges A. J (2015). Understanding service utilization disparities and depression in Latinos: The role of Fatalismo. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17, 1758–1764. doi:10.1007/s10903-015-0196-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckman L., Small B. J., & Fratiglioni L (2001). Stability of the preclinical episodic memory deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 124, 96–102. doi:10.1093/brain/124.1.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1981). Self-referent thought: A developmental analyses of self-efficacy. In J. Flavell & L. Ross (Eds.), Social cognitive development (pp. 200–239). Newark: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1988). Self-regulation of motivation and action through goal systems. In V. Hamilton G. H. Bower, & N. H. Frijda (Eds.), Cognitive perspectives on emotion and motivation (pp. 37–61). Dordrecht, Netherlands: KJuwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1989). Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25, 729–735. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.25.5.729 [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A., & Wood R (1989). Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 805–814. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. L., Lewis T. T., Begeny C. T., Yu L., Bennett D. A., & Wilson R. S (2012). Perceived discrimination and cognition in older African Americans. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 18, 856–865. doi:10.1017/S1355617712000628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. C., Huang C. C., & Hsu K. S (2015). Chronic social stress affects synaptic maturation of newly generated neurons in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 19, pyv097. doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyv097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essed P. (1990). Everyday racism: Reports from women of two cultures. Alameda, CA: Hunter House. [Google Scholar]

- Finch B. K., Kolody B., & Vega W. A (2000). Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 295–313. doi:10.2307/2676322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A. L., Mungas D. M., Crane P. K., Gibbons L. E., MacKay-Brandt A., Manly J. J., … Jones R. N (2015). Effects of education and race on cognitive decline: An integrative study of generalizability versus study-specific results. Psychology and Aging, 30, 863–880. doi:10.1037/pag0000032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., & Bentler P. M (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar]

- Inzelberg R., Afgin A. E., Massarwa M., Schechtman E., Israeli-Korn S. D., Strugatsky R., … Friedland R. P (2013). Prayer at midlife is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline in Arabic women. Current Alzheimer Research, 10, 340–346. doi:10.2174/1567205011310030014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley B., Wright L., & Condit C. M (2009). Functions of health fatalism: fatalistic talk as face saving, uncertainty management, stress relief and sense making. Sociology of Health & Illness, 31, 734–747. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes C. L. (2009). The Black-White paradox in health: flourishing in the face of social inequality and discrimination. Journal of Personality, 77, 1677–1706. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M. E., Neupert S. D., & Agrigoroaei S (2011). The relevance of control beliefs for health and aging. In K. W. Schaie & S. L. Willis (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (pp. 173–190). New York, NY:Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00011-5 [Google Scholar]

- Lachman M. E., & Weaver S. L (1998). The sense of control as a moderator of social class differences in health and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 763–773. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. L., & Ahn S (2012). Discrimination against Latina/os. The Counseling Psychologist, 40, 28–65. doi:10.1177/0011000011403326 [Google Scholar]

- Lefcourt H. M. (2014). Locus of control: current trends in theory and research. Hove: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. T., Aiello A. E., Leurgans S., Kelly J., & Barnes L. L (2010). Self-reported experiences of everyday discrimination are associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels in older African-American adults. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 24, 438–443. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. T., Barnes L. L., Bienias J. L., Lackland D. T., Evans D. A., & Mendes de Leon C. F (2009). Perceived discrimination and blood pressure in older African American and white adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 64, 1002–1008. doi:10.1093/gerona/glp062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. T., Everson-Rose S. A., Powell L. H., Matthews K. A., Brown C., Karavolos K., … Wesley D (2006). Chronic exposure to everyday discrimination and coronary artery calcification in African-American women: the SWAN Heart Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 362–368. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000221360.94700.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T. T., Yang F. M., Jacobs E. A., & Fitchett G (2012). Racial/ethnic differences in responses to the everyday discrimination scale: a differential item functioning analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 175, 391–401. doi:10.1093/aje/kwr287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly J. J., Jacobs D. M., Touradji P., Small S. A., & Stern Y (2002). Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and white elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 8, 341–348. doi:10.1017/S1355617702813157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly J. J., & Mungas D (2015). JGPS special series on race, ethnicity, life experiences, and cognitive aging. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 509–511. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marden J. R., Mayeda E. R., Walter S., Vivot A., Tchetgen Tchetgen E. J., Kawachi I., & Glymour M. M (2016). Using an alzheimer disease polygenic risk score to predict memory decline in black and white americans over 14 years of follow-up. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 30, 195–202. doi:10.1097/WAD.0000000000000137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda E. R., Glymour M. M., Quesenberry C. P., & Whitmer R. A (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 12, 216–224. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J., & Ross C. E (2007). Life course trajectories of perceived control and their relationship to education. American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1339–1382. Doi: 10.1086/511800 [Google Scholar]

- Pérez D. J., Fortuna L., & Alegria M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. doi:10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G., Feaster D. J., Schwartz S. J., Pratt I. A., Smith L., & Szapocznik J (2004). Religious involvement, coping, social support, and psychological distress in HIV-seropositive African American mothers. AIDS and Behavior, 8, 221–235. doi:10.1023/B:AIBE.0000044071.27130.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306 [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J. (1983). Behavioral medicine: Beneficial effects of self control training in aging. International Review of Applied Psychology, 32, 153–181. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1983.tb00901.x [Google Scholar]

- Roncancio A. M., Ward K. K., & Berenson A. B (2011). Hispanic women’s health care provider control expectations: the influence of fatalism and acculturation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22, 482–490. doi:10.1353/hpu.2011.0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C. E., & Mirowsky J (2013). The sense of personal control: social structural causes and emotional consequences. In C. S. Aneshensel J. S. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (Second, pp. 379–402). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_19 [Google Scholar]

- Rosso A. L., Flatt J. D., Carlson M. C., Lovasi G. S., Rosano C., Brown A. F., … Gianaros P. J (2016). Neighborhood socioeconomic status and cognitive function in late life. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183, 1088–1097. doi:10.1093/aje/kwv337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R. M. (2001). Depression, antidepressants, and the shrinking hippocampus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 12320–2. doi:10.1073/pnas.231475998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T., McAvay G., Merrill S., Albert M., & Rodin J (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs and change in cognitive performance: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Psychology and Aging, 11, 538–551. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.11.3.538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnega A., Faul J. D., Ofstedal M. B., Langa K. M., Phillips J. W., & Weir D. R (2014). Cohort profile: The Health and Retirement Study (HRS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43, 576–585. doi:10.1093/ije/dyu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankiewicz A. M., Goscik J., Majewska A., Swiergiel A. H., & Juszczak G. R (2015). The effect of acute and chronic social stress on the hippocampal transcriptome in mice. PLOS ONE, 10, e0142195. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starnes W. R., & Loeb R. C (1993). Locus of control differences in memory recall strategies when confronted with noise. The Journal of General Psychology, 120, 463–471. doi:10.1080/00221309.1993.9711160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M. X., Cross P., Andrews H., Jacobs D. M., Small S., Bell K., … Mayeux R (2001). Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology, 56, 49–56. doi:10.1212/WNL.56.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M. X., Stern Y., Marder K., Bell K., Gurland B., Lantigua R., … Mayeux R (1998). The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA, 279, 751–755. doi:10.1001/jama.279.10.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor W. D., Aizenstein H. J., & Alexopoulos G. S (2013). The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 18, 963–974. doi:10.1038/mp.2013.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames A. D., Hinkin C. H., Byrd D. A., Bilder R. M., Duff K. J., Mindt M. R., … Streiff V (2013). Effects of stereotype threat, perceived discrimination, and examiner race on neuropsychological performance: simple as black and white?Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 19, 583–593. doi:10.1017/S1355617713000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil-Smoller S., Arredondo E. M., Cai J., Castaneda S. F., Choca J. P., Gallo L. C., … Zee P. C (2014). Depression, anxiety, antidepressant use, and cardiovascular disease among Hispanic men and women of different national backgrounds: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of Epidemiology, 24, 822–830. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Yan Yu, Jackson J. S., & Anderson N. B (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351. doi:10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. W., Plassman B. L., Burke J., Holsinger T., & Benjamin S.. (2010). Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 193. (Prepared by the Duke Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290-2007-10066-I; AHRQ Publication No. 10-E005). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. S., Capuano A. W., Sytsma J., Bennett D. A., & Barnes L. L (2015). Cognitive aging in older Black and White persons. Psychology and Aging, 30, 279–285. doi:10.1037/pag0000024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R. E., &Bandura A (1989). Impact of conceptions of ability on self-regulatory mechanisms and complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. V., Shamy J. L., Bedi G., Choi C. W., Wall M. M., Arango V., … Hen R (2014). Impact of social status and antidepressant treatment on neurogenesis in the baboon hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology: Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 39, 1861–1871. doi:10.1038/npp.2014.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne L. B., Manly J. J., Smith J., Seeman T., & Lachman M. E (2017). Socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial mediators of racial disparities in cognition in early, middle, and late adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 32, 118–130. doi:10.1037/pag0000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.