Abstract

Background

Peri-implantitis (PI) is an inflammatory condition that affects the tissues surrounding dental implants. Although the pathogenesis of PI is not fully understood, evidence suggests that the etiology is multifactorial and may include a genetic component.

Objective

To investigate the role of genetics in peri-implantitis development.

Methods

Four-week-old C57BL/6J, C3H/HeJ and A/J male mice had their left maxillary molars extracted. Implants were placed in the healed extraction sockets. Upon osseointegration, ligatures were placed around the implant head for one or four weeks to induce PI. Micro-computed tomography scanning was used to measure volumetric bone loss. Histological analyses were also performed to evaluate collagen organization and the relative presence of neutrophils and osteoclasts.

Results

Radiographically, C57BL/6J mice displayed the greatest amount of bone loss in ligature-treated mice followed by C3H/HeJ and A/J at one and four weeks. Histologically, at one week, C57BL/6J mice presented with the highest numbers of neutrophils and osteoclasts. At four weeks, C57BL/6J mice presented with the most active bone remodeling compared to the other two strains.

Conclusions

There were significant differences in the severity of peri-implantitis among different mouse strains, suggesting that the genetic framework can affect implant survival and success. Future work is needed to dissect the genetic contribution to the development of peri-implantitis.

Keywords: murine, dental implant, bone loss, genetics

Introduction

Peri-implantitis (PI) is characterized by soft tissue inflammation and progressive bone loss around dental implants (1). According to Derks et al., PI affects 45% of patients who received dental implants, with 14.56% of the patients having moderate to severe disease (2). Although PI shares similar characteristics with periodontitis, PI appears to progress more aggressively, and if left untreated can lead to implant loss (3). Given that 450,000 implants are placed in the United States a year (4), PI is a significant clinical concern due to the cumulative number of implants delivered over time.

The pathophysiology of PI is not well understood and a gold standard protocol for treating the condition has not been defined (5–7). Risk factors for PI appear to be similar to those for periodontitis, and include the presence of excess restoration cement, previous periodontal diseases, poor oral hygiene, diabetes, and host or genetic influences (8, 9). While genetic factors have shown to be a significant determinant in the development of periodontitis (10–12), including 50% heritability (10), the genetic contribution to PI is largely unknown. However, several studies have started to investigate genetic mediators in PI using clinical cohorts. Indeed, Laine et al, showed that polymorphisms in IL-1RN were associated with northern Caucasian patients with PI (13). Furthermore, in a clinical study of chronic periodontitis and PI, Casado et al, found that specific BRINP3 polymorphisms and low levels of BRINP3 expression were associated with PI (14). Moreover, it is well documented that previous periodontitis history and environmental factors increase risk for PI, and Garcia-Delaney et al, utilized a clinical study to investigate polymorphisms in IL-1 in smoking patients (15). The incidence of PI was significantly higher in patients with a previous history of periodontitis and both groups shared similar IL-1 polymorphisms. However, there was no increased risk of PI in heavy smokers with IL-1 polymorphisms, suggesting that previous PD risk and host factors may play a larger role in PI risk than environmental factors (15).

We therefore hypothesize that the genetic framework of the individual affects peri-implantitis susceptibility and progression. The goal of this study is to examine whether there is a genetic influence in the susceptibility to PI by employing a murine model using three genetically different inbred mouse strains. Mice are good candidates for this type of translational study because they share similar functional, structural and genetic traits with humans, and can serve as a foundation for identifying genetic variations associated with various stages of PI development, which would be difficult to study in humans (16, 17).

Materials & Methods

Animals

Four-week-old C57BL/6J (n=22), C3H/HeJ (n=22), and A/J (n=21) male mice (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were used following the guidelines of the Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee of the University of California, Los Angeles. In addition, the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines for animal research and submission of studies were followed (18). For the duration of the study, mice were fed a soft diet ad libitum (Bio Serve; Frenchtown, NJ).

Tooth Extraction and Implant Placement

Four-week-old male mice had their first, second, and third maxillary left molars extracted. After eight weeks of natural healing, titanium implants were placed in the extraction sockets. Specialized smooth-surfaced titanium implants were machine fabricated from 6AL4V titanium rods (D.P. Machining Inc., La Verne, CA). Implant specifications were as follows: the threaded surface of the implant was 1.0mm long and 0.5mm in diameter. Each mouse received one implant, as previously described (19). In brief, following anesthetization, a mesio-distal incision was made using a 12D in the maxillary keratinized tissue in the area corresponding to the second molar using the contralateral right side as a reference. Full thickness buccal and palatal flaps were elevated and osteotomy was performed using a manual rotation 0.3mm diameter hand drill (BIG Kaiser Precision Tooling Inc., Hoffman Estates, IL). Titanium implants were screwed into the extraction socket in a clockwise direction. Implants were allowed to osseointegrate for four weeks following placement (19). During the course of tooth extraction and implant placement, mice were given oral antibiotics ad libitum as previously reported (19).

Induction of Peri-Implantitis

Four weeks after implants were placed, osseointegration was assessed clinically based first on the presence/absence of the implant fixture and second by manually applying bucco-lingual wiggling forces to the implants to check for stability. Radiographically, bone levels around the implant fixtures were evaluated based on the distance between the implant head and the bone crest circumferentially (described below).

At four weeks after placement, PI was induced using the silk ligature model previously described (19). Animals were randomly separated into experimental and control groups (n≥5/group/strain/time point). In the experimental ligature group, 6-0 silk ligatures (P.B.N Medicals, Stenløse, Denmark) were tied immediately apical to the implant head. The control group did not receive ligatures. Animals also received an interperitoneal injection of 25mg/Kg calcein (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) at seven and three days before sacrifice.

One or four weeks after ligature placement, the mice were sacrificed, their maxillae harvested and the specimens clinically imaged using a digital optical microscope (Keyence® VHX-1000, Osaka, Japan). Maxillae were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 hours and subsequently stored in 70% EtOH. In the experimental group, if the ligature was not present at the end of the experimental period, the specimen was excluded from the data analysis.

Micro-Computed Tomography Analysis

Maxillae harvested at the one-week and four-week time points were scanned utilizing micro-computed tomography (microCT) (Model 1172; SkyScan, Kontich, Belgium) at 10μm resolution. Volumetric bone loss was measured using CTAn (V.1.16 Bruker, Billerica, MA). Samples were oriented using DataViewer (V.1.5.2 Bruker, Billerica, MA) with the long axis of the implant head being parallel to the sagittal and coronal axes and perpendicular to the axial axis.

Using CTAn, volumetric measurements were taken starting at the 10th slice below the junction of the implant head and the shaft, which would represent a normal volume of soft tissue (biologic soft tissue seal) where bone would not exist in any of the samples, to the alveolar bone crest’s first image. By subtracting the measurement from the implant head to the level of 10th slice, all specimens were normalized to evaluate bone loss. Circumferential volumetric measurements were taken in the axial plane. A single blinded examiner oriented the images and performed the volumetric analysis. Data from each group was averaged to determine the amount of circumferential volumetric bone loss per group.

Histology

Undecalcified samples

Samples from the one-month time point were embedded in methyl methacrylate as previously described, ground coronally to a final thickness of approximately 20μm (Scientific Solutions, LLC, MN), and stained with toluidine blue (19). Samples were imaged using an OLYMPUS BX51 microscope with either bright field, for toluidine blue staining, or a FITC filter, for calcein labeling (Shinjuku Tokyo, Japan).

Decalcified Samples

Maxillae harvested at one and four weeks were first decalcified in 15% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), which was followed by implants being unscrewed in a counterclockwise direction from the specimen. Five μm-thick sections were cut sagittaly using a microtome (McBain Instruments, Chatsworth, CA) as previously described (20). Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and with picrosirius red to assess collagen organization (Polysciences, Inc. Warrington, PA). Picrosirius red-stained slides were imaged in bright field, as well as, under polarized light (OLYMPUS U-Pot lens, Shinjuku Tokyo, Japan). Samples from the one-week time point were additionally stained with Tartrate Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP, Sigma-Aldrich, MO) to assess osteoclast counts, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed utilizing an anti-neutrophil antibody (NIMP-R14, 1:250, Abcam) to assess neutrophil infiltration. Antigen retrieval was performed using 0.5% trypsin for 20 min. at room temperature. Anti-rat secondary (1:200) was incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. The immunoreaction was visualized using Dako AEC substrate chromogen (Agilent Technologies, CA). For TRAP staining, the bone area adjacent to and surrounding the implant head and shaft was used to quantitate osteoclasts, which was achieved by counting multinucleated TRAP+ cells (n=3/group/strain) after the sections were digitally imaged using Aperio Image Scope model V11.1.2.752 (Vista, CA).

Statistical Analysis

The differences between the two groups with respect to the number of implants present at the end of the experimental periods was calculated using the Chi Squared (Fisher’s exact) test (Prism 5, GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA). The data was set up as a contingency table with variables for either the presence (success) or absence (failure) of the implant after four weeks of osseointegration. For volumetric bone loss (n≥4/group/time point) and osteoclast counts (n=3/group/time point), values were averaged for each group (mean ± standard error of the mean) and the statistical differences between and among groups were evaluated using a Student’s t-test and a two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test with a 95% confidence interval. Significance levels were as follows: p≤0.05*, p≤0.01**, p≤0.001*** (Prism 5, GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA).

Results

Clinical and Radiographic Assessment of Implant Osseointegration

Initial implant osseointegration was assessed clinically at four weeks after implant fixture placement (before ligature installation). Clinical evaluation of implant osseointegration as revealed by the presence/absence of implants in the mouth and, if present, clinical signs of mobility, showed no statistical differences among the three different mouse strains. C3H/HeJ mice had 12 of 22 implants initially placed, C57BL/6J mice had 14 of 22 and A/J mice had 14 of 21 implants remaining. None of the surviving implant fixtures showed any detectable mobility.

Implant osseointegration was analyzed radiographically at later time points (five and eight weeks after implant placement). Interestingly, there was a statistical difference in the circumferential bone volume around the axial portion of the implants at the end of the osseointegration period among the three strains. The C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J groups revealed a statistically significantly greater circumferential volumetric absence of bone around the axial portion of the implants as compared to A/J in control groups (Fig. 1D and 1E).

Figure 1. Clinical and radiographical implant assessment at one and four weeks.

(A) Representative clinical images of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) groups one and four weeks after ligature placement. 20X magnification. (B) Representative sagittal micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) images of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) C3H/HeJ, A/J, and C57BL/6J mouse groups four weeks after ligature placement. Notice the reduced alveolar bone in the experimental groups compared to control. (C) Representative axial micro-CT images of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) C3H/HeJ, A/J, and C57BL/6J mouse groups four weeks after ligature placement. Notice the circumferential bone loss around the implants. (D) Graph representing the averaged volumetric bone loss from the implant head to the alveolar bone one week after ligature placement. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (n≥5 for all groups). (E) Graph representing the averaged volumetric bone loss from the implant head to the alveolar bone four weeks after ligature placement. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (n≥5 for all groups).

Clinical Changes in Peri-implantitis Development

Four weeks after implant osseointegration, silk ligatures were placed around the implants in the experimental group while control implants did not receive ligatures. At the end of the experimental periods of one or four weeks after ligature placement, no implants in either the control or experimental (ligature) groups had exfoliated.

Clinically, all ligature treated groups showed increased soft tissue edema compared to their respective controls. C3H/HeJ presented with the most gingival edema in control and ligature groups, at both time points (Fig. 1A).

Radiographic Changes in Peri-Implantitis Development

Radiographically, at one week, there was a statistically significant increase in volumetric bone loss in the C57BL/6J and C3H/HeJ ligature groups compared to their respective controls. A/J mice did not show statistically significant volumetric bone loss differences between the ligature and control groups. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the ligature-treated groups among the three mouse strains. C57BL/6J mice presented with the highest mean volumetric bone loss followed by C3H/HeJ, while A/J mice had the least amount of bone loss (Fig. 1D).

At one month, all three-ligature groups had a statistically significant increase in volumetric bone loss compared to their respective controls. C57BL/6J mice had a statistically higher amount of circumferential bone loss compared to the other two mouse strains (Fig. 1E). Representative radiographic images showed circumferential bone loss around the implants (Fig. 1B and 1C).

Early Histological Changes in Peri-implantitis Development

To assess cellular changes during peri-implantitis development, samples from the control and ligature groups were analyzed histologically through H&E, picrosirius red (collagen composition) and TRAP (osteoclast) staining. In addition, immunohistochemistry was performed to assess neutrophil infiltrate (NIMP-R14).

Histologically, through H&E staining, at one week, the control (no ligature) groups presented with normal epithelial and submucosal architecture and close bone contact was observed in all strains. However, the bone quality in the ligature groups was different among the three different strains. The alveolar bone in the A/J ligature group was largely dense (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the alveolar bone quality in the ligature groups of C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J appeared less dense (Fig. 2A and 2B). Similar findings were observed in the control and ligature groups four weeks after ligature placement (Appendix Figure 1).

Figure 2. Histological evaluation one week after ligature placement.

(A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sagittal sections of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) groups. Note the increased soft tissue edema in experimental groups. 4X magnification. (B) 20X magnification of the area corresponding to the black square in (A). Note the increased alveolar bone porosity in ligature treated groups.

Appendix Figure 1.

Histological evaluation four weeks after ligature placement. (A) Representative H&E stained sections of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) groups. 4X magnification. (B) 20X magnification of the area corresponding to the black square in (A).

Histologically, through picrosirius red staining at one week, the Type 1 collagen in the soft and hard tissue appeared more organized and parallel to the implant head in the control groups. However, in the ligature groups, collagen organization in the soft and hard tissue appeared disrupted and oriented perpendicular to the implant head (Fig. 3A and 3B).

Figure 3. Collagen composition one week after ligature placement.

(A) Representative bright field and picrosirius red stained sagittal sections of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) groups. 10X magnification. (B) 20X magnification of the area corresponding to the white square in (A).

Comparing all three-ligature groups, the C57BL/6J ligature group appeared to have less Type 1 collagen, shown by the decreased yellow birefringence in the area of the soft tissue under polarized light (Fig. 3B). At four-weeks, picrosirius red staining still showed organized parallel Type 1 collagen fibers in all the controls groups. In the ligature treated groups, collagen appeared more disorganized and perpendicular to the implant head (Appendix Figure 2).

Appendix Figure 2.

Collagen composition four weeks after ligature placement. (A) Representative bright field and picrosirius red stained sagittal sections of control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) groups. 10X magnification. (B) 20X magnification of the area corresponding to the black square in (A).

Neutrophils were further evaluated to characterize the onset of peri-implantitis at the one-week time-point. There did not appear to be any differences in the number of neutrophils in the control groups among the three mouse strains. However, one week after ligature placement, C57BL/6J presented with a higher neutrophil number compared to the other two ligature-treated groups (Fig. 4A).

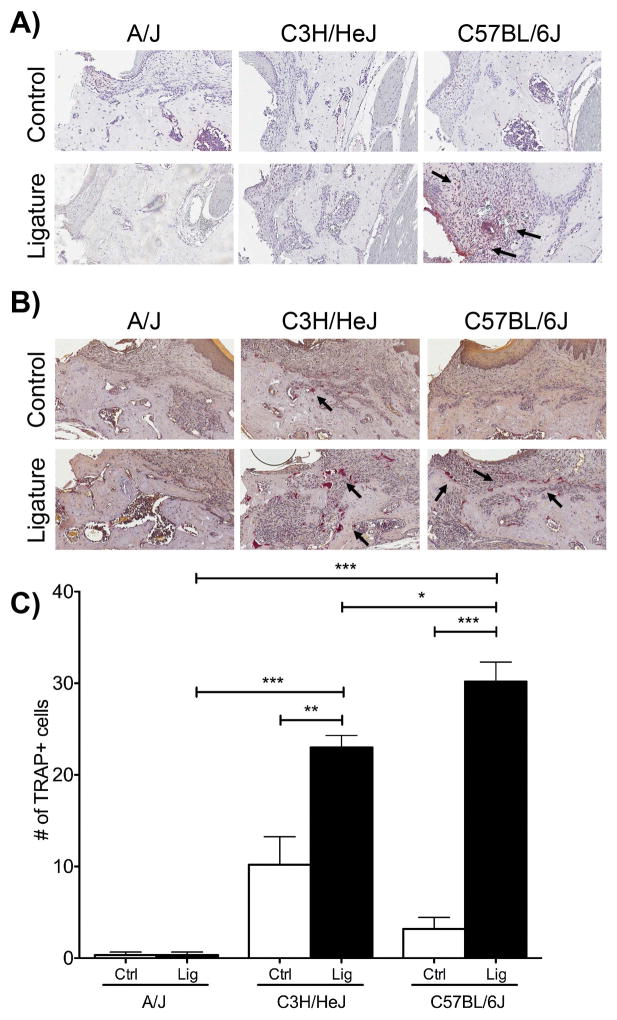

Figure 4. Early assessment in neutrophil and osteoclast numbers.

(A) NIMP-R14 immunohistochemistry, neutrophil staining, in alveolar bone and infiltrated connective tissue adjacent to the implant sites. Implants were removed before embedding the decalcified specimens. 20X magnification. (B) TRAP staining, osteoclastic cells (C) Graph representing the averaged number of osteoclasts in C3H/HeJ, A/J, and C57BL/6J control (no ligature) and experimental (ligature) groups. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 (n≥3 for all groups).

Osteoclasts numbers were evaluated, through TRAP staining, at the one-week time point. Evaluating osteoclast numbers in the control groups, there was no statistical significance in the number of osteoclasts among the three strains. After ligature placement osteoclast numbers were statistically significantly increased in the C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J mice compared to their respective controls. C57BL/6J had the highest number of osteoclasts (30.2 ± 2.131) followed by C3H/HeJ (23.00 ± 1.304) and A/J mice (0.333 ± 0.333) (Fig. 4B and 4C).

Late Histological Changes in Peri-implantitis Development

In order to profile late changes in peri-implantitis development, samples from the four-week time point were further analyzed with toluidine blue staining and calcein labeling on undecalcified samples. Undecalcified toluidine blue (TB) staining at four weeks revealed similar findings to the H&E stain (Fig. 5). TB staining showed bone (blue) in direct contact to the implant threads in all control groups. In the ligature groups, the bone loss is evident in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J with bone levels almost down to the second to third implant threads. Calcein labeling showed increased fluorescence in the C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J strains compared to the A/J strain. The C57BL/6J ligature group showed calcein labeling specifically in the area where the ligature was placed and bone loss had occurred (Fig. 5). These findings are consistent with C57BL/6J ligature mice presenting with the largest amount of volumetric bone loss.

Figure 5. Late Histological Changes in bone-implant interface.

Histology of bone-implant interfaces in ground, undecalcified sections at four weeks after ligature placement by toluidine blue stain and calcein labeling (green fluorescence, FITC). 10X magnification. Note increased green fluorescence in the C57BL/6J experimental (ligature) group as compared to C3H/HeJ and A/J.

Discussion

In this study, we utilized an experimental model of PI (19) on three different mouse strains to investigate the role of different genetic profiles on implant osseointegration and PI susceptibility and development.

Although there was no statistical significance in implant retention among the three strains, there was a statistically significant difference in the volume of circumferential bone around the axial portion of the implants in the control mice among the three different strains implying a genetic influence in the bone level during osseointegration. A/J control mice had a statistically significantly higher bone level around the implant fixture compared to C3H/HeJ and C57BL/6J. These variations in initial implant integration could be due to initial bone modeling or remodeling. Given the initial differences, our study suggests that genetic variations can play a role in the initial bone level after implant placement. These results corroborate with the findings of Cosyn et al, where initial implant osseointegration could be at least partially attributed to genetics (21).

Peri-implantitis development was also statistically significantly different among the three genetically different mouse strains. Specifically, the C57BL/6J ligature group presented with increased circumferential volumetric bone loss, increased osteoclasts numbers, and a higher neutrophil presence compared to the C3H/HeJ and A/J groups. Interestingly, the peri-implantitis data presented here follows a similar pattern observed in our experimental periodontitis model on genetically different mouse strains (11). In our periodontitis study, C57BL/6J was also the most susceptible strain followed by C3H/HeJ and then A/J (11) suggesting pathophysiological correlations between the two conditions. Moreover, our current study concurs with other studies that identified the genetic importance of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as a risk factor for peri-implantitis (21–25). In addition, our data in conjunction with published data, suggests that peri-implantitis, like periodontitis, is a complex trait disease, in which, multiple genetic polymorphisms act in concert to increase disease risk (21–26). Corroborating with a complex trait disease model for peri-implantitis, a meta-analysis evaluating the role of IL-1 in peri-implantitis showed that while there was not a significant effect of IL-1A or IL-1B individually, a composite polymorphism phenotype with IL-1A and IL-1B was associated with an increase risk for implant failure and subsequent peri-implantitis (24).

In our study, the distinct responses to experimental PI observed among the different strains are most likely due to inherent differences in immune response and bone modeling/remodeling. For instance, the antagonistic phenotypes observed in A/J and C57BL/6J have already been evaluated in many systems including, neutrophil physiology, inflammatory infiltrate response, and macrophage response to LPS. Moreover, in vitro studies demonstrated that after LPS stimulation, A/J presents with a decreased neutrophil infiltration and diminished acute inflammation, and A/J macrophages express lower levels of IL-1 compared to C57BL/6J, (27, 28) which is consistent with the reduced neutrophil counts in A/J mice compared to C57BL/6J observed in our present study following PI development. Due to inherent immune and inflammatory host response differences, and their resistance and susceptibility to PI, A/J, C3H/HeJ, and C57BL/6J make suitable animal models for understanding the genetic differences that contribute to peri-implantitis. In addition, understanding if there are differences in the microbiome among these strains is of utmost importance.

As mentioned earlier, animal studies can offer significant insight into the role of genetics in disease development mainly because genetic studies in humans have intrinsic limitations including: lack of environmental control, small samples sizes, the use of specific ethnic cohorts, and the genetic heterogeneity of patient populations (17). Studies of PI have utilized dogs, rats, and non-human primates to investigate the differences between ligature-induced PI and PD, as well as, differences in bacterial colonization in both conditions (29–34). Currently, there are many acceptable models to induce PD, including local delivery of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) through injections, oral gavage, and the use of ligatures placed around molars (35–37). While each model has limitations in study design, clinical correlations can be drawn in order to better understand disease pathogenesis. By evaluating host response differences to experimentally induced PD in mice, de Molon et al revealed that the ligature method produced significant alveolar bone loss in the initial period and that bone loss was maintained throughout the experimental timeline (35). While methods such as oral gavage to induce bacterial colonization via a bacterial cocktail may more accurately represent a disease scenario, studies have shown low reproducibility and high variability in the amount of bone loss (35). None-the-less, through these studies, significant knowledge has been gained including that PI induced in dog models is similar in configuration and size to human defects (38), as well as, biofilm colonization on implants placed in dogs produces a significant increase in the number of inflammatory cells (39). Focusing on rodent models of bacterial-induced peri-implantitis, Freire et al. were able to colonize Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (A.a.) on titanium implants that were subsequently placed in the rat hard palate (40). Through this model, Freire et al. were able to induce bone loss, as well as, establish a bacterial biofilm-mediated rodent peri-implantitis model. Freire et al.’s rodent model differed from ours given that the colonization occurred prior to implant osseointregration (40). However, a recent study by Tzach-Nahman et al, employed a murine model of experimental PI where after implant placement and osseointegration, mice were challenged with P. gingivalis (P.g.) oral gavage (41). Through this model, the authors observed that mice challenged with P.g. exhibited greater bone loss around implants and increased TNF-alpha expression six weeks after infection (41). Although, some information has been gathered about bacterial colonization and host response, detailed differences in bacterial colonization on natural teeth and dental implants, as well as, differences in genetic host response to bacterial colonization and changes in gene expression are areas that need to be further explored.

Animal models, and specifically mice, allow tight environmental control and reproducibility. Additionally, mice share similar oral facial and genetic characteristics to humans and there are large genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic databases available in order to identify genes and signaling pathways that can be translated back to human studies (42–44). Two groups, including our own, have utilized the mouse to interrogate experimental PI (19, 45) with overlapping results, again highlighting the reproducibility of these study designs. Several mouse panels have been developed in order to perform detailed genetic interrogation of diseases including the Collaborative Cross (CC) (46) and the Hybrid Mouse Diversity Panel (HMDP) (47). Herein we utilized three strains that derive several recombinant strains of the HMDP. The HMDP, is a panel of more than 100 classic and recombinant inbred strains genotyped for ~650,00 SNPs, which allows for high mapping resolution and statistical phenotype to genotype association (48). The HMDP has successfully been utilized to dissect complex traits including conditioned fear response, plasma lipids, gene-by-diet interactions in obesity, diabetes, inflammatory responses, and heart failure. (49–55). Most importantly, the HMDP has been successfully employed in translational studies including validation of genetic loci in humans that regulate liver metabolites (55) increasing the validity of our study. Furthermore, mouse strain overlap in both the CC and HMDP, such as A/J and C57BL/6J serving as parental strains for both panels, could facilitate for the CC and/or the HMDP to be utilized.

Additionally, our studies provide useful mouse models for the study of PI by other investigators. For example, if potential PI treatments are explored, the choice of C57BL/6J mice as the experimental strain would provide maximum PI induced bone loss and immunological responses at baseline, such that interventional effects or treatments would be easier to observe. Alternatively, if PI complicating factors are the focus, A/J mice would show low levels of baseline bone loss such that compounding effects would be more clearly depicted.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the genetic framework of an individual could play a role in peri-implantitis susceptibility and progression. While future work is needed to tease out the intricate genetic players in peri-implantitis, our study serves as a foundation for further systematic genetic interrogation of peri-implantitis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIDCR DE023901-01 and a UCLA School of Dentistry Seed Grant. SH was supported by NIH/NIDCR T90 DE022734-01. We would like to thank Dr. Renata Pereira, from the Bone Histomorphometry Core Facility at the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine for her assistance with the undecalcified plastic sections. We would also like to thank the UCLA Tissue Pathology Core Laboratory for the decalcified histological sections. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Mombelli A, Lang NP. The diagnosis and treatment of peri-implantitis. Periodontology 2000. 1998;17:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Derks J, Schaller D, Hakansson J, Wennstrom JL, Tomasi C, Berglundh T. Effectiveness of Implant Therapy Analyzed in a Swedish Population: Prevalence of Peri-implantitis. Journal of dental research. 2016;95:43–49. doi: 10.1177/0022034515608832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carcuac O, Berglundh T. Composition of human peri-implantitis and periodontitis lesions. Journal of dental research. 2014;93:1083–1088. doi: 10.1177/0022034514551754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sullivan RM. Implant dentistry and the concept of osseointegration: a historical perspective. Journal of the California Dental Association. 2001;29:737–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heitz-Mayfield LJ, Lang NP. Comparative biology of chronic and aggressive periodontitis vs. peri-implantitis. Periodontology 2000. 2010;53:167–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faveri M, Figueiredo LC, Shibli JA, Perez-Chaparro PJ, Feres M. Microbiological diversity of peri-implantitis biofilms. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2015;830:85–96. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-11038-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fransson C, Lekholm U, Jemt T, Berglundh T. Prevalence of subjects with progressive bone loss at implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16:440–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klokkevold PR, Han TJ. How do smoking, diabetes, and periodontitis affect outcomes of implant treatment? The International journal of oral & maxillofacial implants. 2007;22(Suppl):173–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a current understanding of their diagnoses and clinical implications. Journal of periodontology. 2013;84:436–443. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.134001. No Authors Given. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michalowicz BS, Diehl SR, Gunsolley JC, et al. Evidence of a substantial genetic basis for risk of adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1699–1707. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiyari S, Atti E, Camargo PM, et al. Heritability of periodontal bone loss in mice. J Periodontal Res. 2015;50:730–736. doi: 10.1111/jre.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinane DF, Shiba H, Hart TC. The genetic basis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2005;39:91–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laine ML, Leonhardt A, Roos-Jansaker AM, et al. IL-1RN gene polymorphism is associated with peri-implantitis. Clinical oral implants research. 2006;17:380–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casado PL, Aguiar DP, Costa LC, et al. Different contribution of BRINP3 gene in chronic periodontitis and peri-implantitis: a cross-sectional study. BMC oral health. 2015;15:33. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Delaney C, Sanchez-Garces MA, Figueiredo R, Sanchez-Torres A, Gay-Escoda C. Clinical significance of interleukin-1 genotype in smoking patients as a predictor of peri-implantitis: A case-control study. Medicina oral, patologia oral y cirugia bucal. 2015;20:e737–743. doi: 10.4317/medoral.20655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mouse Genome Sequencing C. Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flint J, Eskin E. Genome-wide association studies in mice. Nature reviews Genetics. 2012;13:807–817. doi: 10.1038/nrg3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: The ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. Journal of pharmacology & pharmacotherapeutics. 2010;1:94–99. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.72351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pirih FQ, Hiyari S, Barroso AD, et al. Ligature-induced peri-implantitis in mice. Journal of periodontal research. 2015;50:519–524. doi: 10.1111/jre.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirih FQ, Hiyari S, Leung HY, et al. A Murine Model of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Peri-Implant Mucositis and Peri-Implantitis. The Journal of oral implantology. 2015;41:e158–164. doi: 10.1563/aaid-joi-D-14-00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cosyn J, Christiaens V, Koningsveld V, et al. An Exploratory Case-Control Study on the Impact of IL-1 Gene Polymorphisms on Early Implant Failure. Clinical implant dentistry and related research. 2016;18:234–240. doi: 10.1111/cid.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Z, Wang H, Sun Z, Luo W, Wu Y. Expression of IL-22, IL-22R and IL-23 in the peri-implant soft tissues of patients with peri-implantitis. Archives of oral biology. 2013;58:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadkhodazadeh M, Ebadian AR, Amid R, Youssefi N, Mehdizadeh AR. Interleukin 17 receptor gene polymorphism in periimplantitis and chronic periodontitis. Acta medica Iranica. 2013;51:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liao J, Li C, Wang Y, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between common interleukin-1 polymorphisms and dental implant failure. Molecular biology reports. 2014;41:2789–2798. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakic M, Petkovic-Curcin A, Struillou X, Matic S, Stamatovic N, Vojvodic D. CD14 and TNFalpha single nucleotide polymorphisms are candidates for genetic biomarkers of peri-implantitis. Clinical oral investigations. 2015;19:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00784-014-1313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinane DF, Hart TC. Genes and gene polymorphisms associated with periodontal disease. Critical reviews in oral biology and medicine : an official publication of the American Association of Oral Biologists. 2003;14:430–449. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Malley J, Matesic LE, Zink MC, et al. Comparison of acute endotoxin-induced lesions in A/J and C57BL/6J mice. The Journal of heredity. 1998;89:525–530. doi: 10.1093/jhered/89.6.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brandwein SR, Maenz L. Defective lipopolysaccharide-induced production of both interleukin 1 alpha and interleukin 1 beta by A/J mouse macrophages is posttranscriptionally regulated. Journal of leukocyte biology. 1992;51:570–578. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.6.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marinello CP, Berglundh T, Ericsson I, Klinge B, Glantz PO, Lindhe J. Resolution of ligature-induced peri-implantitis lesions in the dog. Journal of clinical periodontology. 1995;22:475–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zechner W, Kneissel M, Kim S, Ulm C, Watzek G, Plenk H., Jr Histomorphometrical and clinical comparison of submerged and nonsubmerged implants subjected to experimental peri-implantitis in dogs. Clinical oral implants research. 2004;15:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber HP, Fiorellini JP, Paquette DW, Howell TH, Williams RC. Inhibition of peri-implant bone loss with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug flurbiprofen in beagle dogs. A preliminary study. Clinical oral implants research. 1994;5:148–153. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrahamsson I, Berglundh T, Lindhe J. Soft tissue response to plaque formation at different implant systems. A comparative study in the dog. Clinical oral implants research. 1998;9:73–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1998.090202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koutouzis T, Eastman C, Chukkapalli S, Larjava H, Kesavalu L. A Novel Rat Model of Polymicrobial Peri-Implantitis: A Preliminary Study. Journal of periodontology. 2017;88:e32–e41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schou S, Holmstrup P, Stoltze K, Hjorting-Hansen E, Fiehn NE, Skovgaard LT. Probing around implants and teeth with healthy or inflamed peri-implant mucosa/gingiva. A histologic comparison in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Clinical oral implants research. 2002;13:113–126. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Molon RS, de Avila ED, Boas Nogueira AV, et al. Evaluation of the host response in various models of induced periodontal disease in mice. Journal of periodontology. 2014;85:465–477. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves DT, Fine D, Teng YT, Van Dyke TE, Hajishengallis G. The use of rodent models to investigate host-bacteria interactions related to periodontal diseases. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2008;35:89–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sartori R, Li F, Kirkwood KL. MAP kinase phosphatase-1 protects against inflammatory bone loss. Journal of dental research. 2009;88:1125–1130. doi: 10.1177/0022034509349306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarz F, Herten M, Sager M, Bieling K, Sculean A, Becker J. Comparison of naturally occurring and ligature-induced peri-implantitis bone defects in humans and dogs. Clinical oral implants research. 2007;18:161–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ericsson I, Berglundh T, Marinello C, Liljenberg B, Lindhe J. Long-standing plaque and gingivitis at implants and teeth in the dog. Clinical oral implants research. 1992;3:99–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1992.030301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freire MO, Sedghizadeh PP, Schaudinn C, et al. Development of an animal model for Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans biofilm-mediated oral osteolytic infection: a preliminary study. Journal of periodontology. 2011;82:778–789. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tzach-Nahman R, Mizraji G, Shapira L, Nussbaum G, Wilensky A. Oral infection with P. gingivalis induces peri-implantitis in a murine model: evaluation of bone loss and the local inflammatory response. Journal of clinical periodontology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maddatu TP, Grubb SC, Bult CJ, Bogue MA. Mouse Phenome Database (MPD) Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:D887–894. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith CM, Finger JH, Hayamizu TF, et al. The mouse Gene Expression Database (GXD): 2014 update. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:D818–824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Blake JA, Kadin JA, Richardson JE Mouse Genome Database G. The mouse genome database: genotypes, phenotypes, and models of human disease. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:D885–891. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen Vo TN, Hao J, Chou J, et al. Ligature induced peri-implantitis: tissue destruction and inflammatory progression in a murine model. Clinical oral implants research. 2017;28:129–136. doi: 10.1111/clr.12770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Churchill GA, Airey DC, Allayee H, et al. The Collaborative Cross, a community resource for the genetic analysis of complex traits. Nature genetics. 2004;36:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/ng1104-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghazalpour A, Rau CD, Farber CR, et al. Hybrid mouse diversity panel: a panel of inbred mouse strains suitable for analysis of complex genetic traits. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2012;23:680–692. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9411-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rau CD, Parks B, Wang Y, et al. High-Density Genotypes of Inbred Mouse Strains: Improved Power and Precision of Association Mapping. G3. 2015;5:2021–2026. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.020784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bennett BJ, Farber CR, Orozco L, et al. A high-resolution association mapping panel for the dissection of complex traits in mice. Genome research. 2010;20:281–290. doi: 10.1101/gr.099234.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis RC, van Nas A, Bennett B, et al. Genome-wide association mapping of blood cell traits in mice. Mammalian genome : official journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society. 2013;24:105–118. doi: 10.1007/s00335-013-9448-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park CC, Gale GD, de Jong S, et al. Gene networks associated with conditional fear in mice identified using a systems genetics approach. BMC systems biology. 2011;5:43. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parks BW, Nam E, Org E, et al. Genetic control of obesity and gut microbiota composition in response to high-fat, high-sucrose diet in mice. Cell metabolism. 2013;17:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parks BW, Sallam T, Mehrabian M, et al. Genetic architecture of insulin resistance in the mouse. Cell metabolism. 2015;21:334–346. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rau CD, Wang J, Avetisyan R, et al. Mapping genetic contributions to cardiac pathology induced by Beta-adrenergic stimulation in mice. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2015;8:40–49. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghazalpour A, Bennett BJ, Shih D, et al. Genetic regulation of mouse liver metabolite levels. Molecular systems biology. 2014;10:730. doi: 10.15252/msb.20135004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]