Abstract

Objective

The development of the Transition Readiness Inventory (TRI) item pool for adolescent and young adult childhood cancer survivors is described, aiming to both advance transition research and provide an example of the application of NIH Patient Reported Outcomes Information System methods

Methods

Using rigorous measurement development methods including mixed methods, patient and parent versions of the TRI item pool were created based on the Social-ecological Model of Adolescent and young adult Readiness for Transition (SMART)

Results

Each stage informed development and refinement of the item pool. Content validity ratings and cognitive interviews resulted in 81 content valid items for the patient version and 85 items for the parent version

Conclusions

TRI represents the first multi-informant, rigorously developed transition readiness item pool that comprehensively measures the social-ecological components of transition readiness. Discussion includes clinical implications, the application of TRI and the methods to develop the item pool to other populations, and next steps for further validation and refinement.

Keywords: adolescence, assessment, cancer, chronic illness, transition readiness

Similar to other adolescent and young adults (AYA) with pediatric disease, engagement in adult-oriented follow-up care is suboptimal for the growing population of AYA childhood cancer survivors. Despite being cured of their disease, they are vulnerable to treatment-related morbidities, known as late effects, and are at increased risk for adult cancer (Armstrong etal., 2014; Oeffinger etal., 2006). Guidelines recommend annual life-long follow-up care for surveillance and management of treatment-related late effects (Children's Oncology Group, 2013). Unfortunately, <20% of adult survivors of pediatric cancer receive adult-based medical care related to their prior cancer (Nathan etal., 2008), leaving them at risk for poor self-management and delayed diagnosis of significant cancer-related health problems. Thus, the health of AYA survivors is dependent on the transition to, and sustained engagement in, adult medical care.

The challenges of the transition process for survivors, as is the case for all pediatric populations, are multifaceted and multisystemic given the need to consider multiple stakeholders and aspects of AYA disease management and development. Such challenges are exacerbated by a lack of valid measures of transition readiness to assess stakeholder challenges and inform the transition process (McPheeters etal., 2014; Schwartz etal., 2014). In this study, we describe the development of the Transition Readiness Inventory (TRI) item pool for childhood cancer survivors, which is a set of vetted and refined items before large-scale validation. The study fills the need for more valid transition readiness measures in childhood cancer and beyond, while also serving as a model for the rigorous development of an item pool in a burgeoning and complex area of research.

Transition readiness refers to indications that a patient and those in their support system (e.g., parents and providers) can successfully transition from child-centered to adult-oriented health care (Betz & Telfair, 2007; Telfair, Alexander, Loosier, Alleman-Velez, & Simmons, 2004). Despite calls for evidenced-based assessment of AYA transition readiness (Crowley, Wolfe, Lock, & McKee, 2011; Freed & Hudson, 2006; Henderson, Friedman, & Meadows, 2010; Schwartz etal., 2014; Wood etal., 2014) and national initiatives for improving transition from child-centered to adult-centered health care (e.g., the American Academy of Pediatrics transition algorithm and The Maternal and Child Health Bureau and The National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health “Got Transition” program), few validated measures exist that assess and track transition readiness for AYA patients with chronic health conditions (McPheeters etal., 2014; Schwartz etal., 2014).

In a prior review, the authors identified 56 measures of transition readiness (Schwartz etal., 2014). Of the 56 measures, only 10 reported psychometric data in peer-reviewed publications and met the American Psychological Association Division 54 Evidence-Based Assessment Task Force criteria for a “promising assessment.” No data on the predictive validity for transition outcomes were available, and the measures were not tested in more than one sample. Further, most of the measures were not theoretically informed or developed with rigorous methods of measurement development, such as eliciting stakeholder feedback or assessing multiple indices of validity. To date, the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) represents the most evidence-based transition readiness measure (Sawicki etal., 2011; Wood etal., 2014). However, the TRAQ focuses on broad disease management skills (e.g., filling a prescription and calling the doctor’s office to make an appointment), which may or may not have relevance to off-treatment survivors. Further, the TRAQ does not capture the broad range of social-ecological factors (e.g., beliefs/expectations and motivation) that are theoretically important for transition readiness (Schwartz etal., 2013; Schwartz etal., 2014). Only two transition readiness measures were specifically designed for childhood cancer survivors, and neither measure provides information about the predictive validity to long-term follow-up care, broadly assesses social-ecological components of transition, or assesses potential barriers to continuing treatment in the adult-focused medical system [i.e., The Readiness Transition Questionnaire (J. Gilleland, Amaral, Mee, & Blount, 2012; J. Gilleland etal., 2013); Cancer Worry, Self-Management Skills, and Expectations scales (Klassen etal., 2015)]. Further, neither measure assesses the perspectives or feedback of other key transition stakeholders such as the patient’s parents and providers.

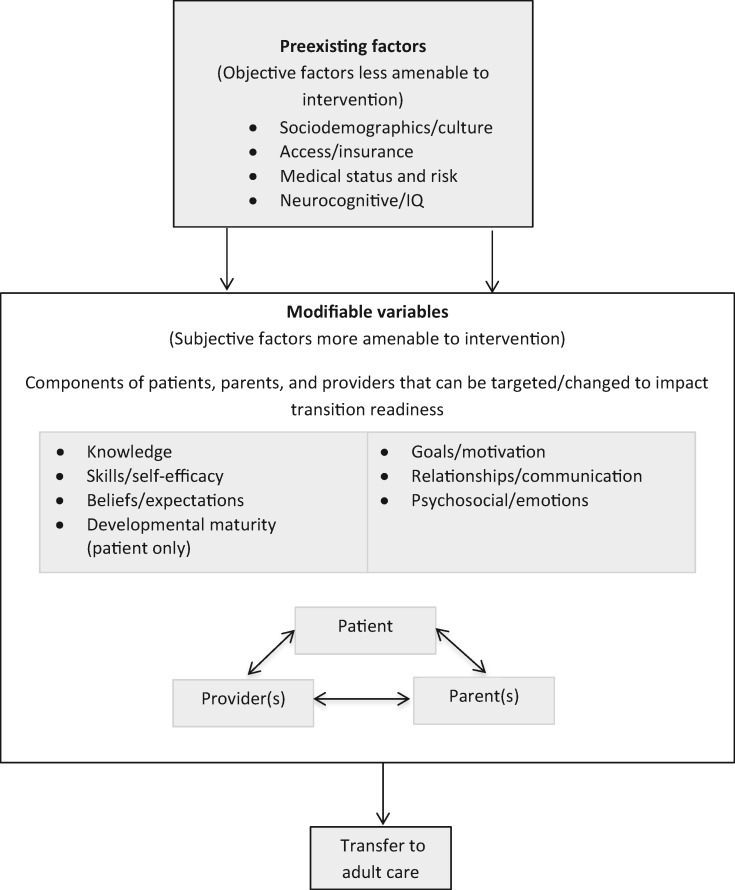

The validated Social-ecological Model of AYA Readiness to Transition (SMART, see Figure 1), which has been applied to multiple pediatric populations (Mulchan, Valenzuela, Crosby, & Sang, 2016; Paine etal., 2014; Pierce & Wysocki, 2015; Szalda etal., 2016), is a model of transition readiness that incorporates multiple systems and components consistent with social ecology and other models of disease management and adaptation to pediatric chronic illness (Schwartz etal., 2011). It can help guide the development of transition readiness measures, as it addresses the need for a more theoretically informed and comprehensive approach. As a systems-based approach, SMART moves beyond the assessment of skills and disease knowledge to measure contextual barriers and facilitators in the transition process that have been deemed important and relevant by multiple stakeholders (Schwartz etal., 2011; 2013). SMART also emphasizes the reciprocal relationship of multiple ecological factors, stakeholders, and systems that influence transition readiness from child-centered to adult-oriented health care. SMART suggests that transition readiness may be influenced by preexisting objective indicators that are less amenable to change (e.g., sociodemographics/culture, health status/risk, access/insurance, and neurocognition/IQ), as well as by subjective indicators that are modifiable and potential targets for intervention (e.g., knowledge, skills/self-efficacy, beliefs/expectations, goals/motivation, relationships/communication, and psychosocial functioning/emotions of patients, parents, and providers). Patient developmental maturity is an overarching component in the model that incorporates the other modifiable components.

Figure 1.

The Social-ecological Model of AYA Readiness to Transition to Adult Care (SMART). Reprinted with permission from JAMA Pediatrics. Original source: Schwartz LA, Brumley LD, Tuchman LK, etal. Stakeholder Validation of a Model of Readiness for Transition to Adult Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2013.

In this article, we describe the development of the SMART-informed and multi-informant TRI item pool for childhood cancer survivors. Measurement development methods were those used and endorsed by NIH’s Patient Reported Outcomes Information System (PROMIS; Cella etal., 2007; DeWalt, Rothrock, Yount, & Stone, 2007). PROMIS standardizes the process of and describes the most rigorous methods of development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures (Cella etal., 2007; DeWalt etal., 2007). Use of PROMIS-endorsed methodology for pediatric PROs has been prioritized nationally, including in pediatric psychology (Forrest etal., 2012). Yet, to our knowledge, no measure in pediatric psychology has been developed explicitly following PROMIS-endorsed methods and steps.

The present study extends the literature by addressing a need for childhood cancer survivorship care with the development of a new transition readiness tool, while also being among the first to develop a transition readiness measure following rigorous PROMIS-endorsed methodology called for in pediatric psychology (Forrest etal., 2012). Given the complexity of the transition readiness construct and the lack of valid measures, the application of such rigorous methods is particularly important for a measure of transition readiness. By applying rigorous PROMIS methods, which includes specifying the domain and qualitative data collection to assess clarity and relevance, we aim to contribute to the conceptualization of transition readiness and describe methods for developing measures for this complex construct. Methods may be replicated to generate theoretically informed, multi-informant transition readiness measures for other AYA disease populations, which would significantly advance the study of and promotion of transition readiness across pediatric populations. Therefore, PROMIS methods described are also intended to serve as an example of the application of such methods to patient reported outcome (PRO) development in pediatric psychology.

Method

Consistent with PROMIS methods and measurement development guidelines proposed by Holmbeck and Devine (2009), item pool development consisted of domain/item bank concept elicitation and specification, item development (e.g., extant instrument identification and literature review, content validity ratings, item concept classification, additional item development), and cognitive interviews for further refinement (Cella etal., 2007; DeWalt etal., 2007; Forrest etal., 2012).

Step 1: Transition Readiness Concept Specification

The SMART model informed the theoretical framework for TRI. The specific methods of SMART development and validation have been described in detail elsewhere (Schwartz etal., 2011; Schwartz etal., 2013) and summarized here. SMART validation methods included the following: (1) incorporating input on SMART from an expert panel of providers in AYA medicine and oncology (i.e., physicians, nurses, and psychologists) and (2) conducting a mixed-methods validation study of SMART, which included focus groups with patients (N = 14) and parents (N = 15), individual interviews with providers (N = 10), and a survey of ratings on the SMART components’ general relevance and importance to AYA patients (Schwartz etal., 2013).

Step 2: Item Classification and Development: Binning and Winnowing, Item Revisions and Development, and Content Validity Ratings

To identify extant transition readiness measures, we conducted an extensive literature review that included a comprehensive, multidatabase search of academic (PsycInfo, Medline, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, PubMed) and online search engines using relevant combinations of the following key words: healthcare transition, medical transition, transition readiness, adult care, transfer, chronic illness, chronic health condition, young adult, adolescent, assessment, questionnaire, checklist, measure, survey, and tool. Additional measures were found via personal correspondence with experts in the field (such as those presented at a conference) and by checking references of extant measures (Schwartz etal., 2012). To be included in the review, a measure needed to meet the following criteria: (1) self-described measure of transition readiness, (2) related to chronic physical health condition(s), and (3) administered in English. We applied the following exclusion criteria for measures in the review: (1) a list of general guidelines, (2) an open-ended worksheet, (3) a single-item measure, (4) a measure that specifically targeted mental health or developmental disorders, (5) not self-identified as a transition readiness measure, and (6) did not assess a theoretically or empirically supported construct of transition readiness. Both generic (intended to be generalizable across conditions) and condition-specific measures were included, as well as measures that were interview-based or questionnaire format. We included measures of patient, parent, and/or provider report of transition readiness.

Per PROMIS guidelines for classification, or “binning” (DeWalt etal., 2007), a research assistant coded items into the 11 SMART components: the four preexisting factors that are less amenable to change (sociodemographics/culture, access/insurance, medical status/risk, and neurocognitive functioning/IQ), the six subjective components that are amenable to change and are potential targets of intervention (knowledge, skills/self-efficacy, beliefs/expectations, goals/motivation, relationships/communication, and psychosocial functioning/emotions), and the one component of development of the patient. Although items may have been relevant to more than one category, they were initially assigned to only one bin. Next, a second, unblinded team member reviewed the binning and noted discrepancies if she felt an item should be assigned to another bin. In the event of item discrepancy, the coders reviewed the binning with the principal investigator (and in team meetings if further discussion was needed) and resolved discrepancies through discussion and consensus about bin assignment or removal (as described below). Such discussion is intended to strengthen the construct conceptualization and assure that the items best represent the intended construct.

To further reduce the items, the multidisciplinary team used the process of “winnowing” to omit items. The same process of binning, using multiple coders, was used. Items were “winnowed” that were unclear (poorly worded, questionable relevance to transition readiness), redundant (multiple items tapping the same content), or not generalizable across medical conditions (DeWalt etal., 2007). For example, items from self-identified disease-specific measures that addressed particular needs of that disease population were omitted. Most items were also revised and reworded for clarity, consistency, and standardized answer response options (e.g., most items formatted to have response options on a 5-point scale indicating level of agreement or frequency). Next, new items were generated to fill gaps of SMART subdomains not adequately covered by existing items.

A national scientific advisory committee (n = 8; same committee that reviewed SMART) representing adolescent medicine, nursing, public health, pediatric psychology, and family medicine professionals with expertise in pediatric oncology, adherence, disease self-management, transition, and survivorship care provided feedback and content validity ratings on the collective item pool (TRI). Committee members rated TRI items for relevance (the degree to which an item represented an associated SMART concept on a 4-point scale, where 1 = not relevant and 4 = highly relevant) and clarity (the degree to which the wording of an item is easy to understand rather than confusing on a 4-point scale, where 1 = very confusing and 4 = very clear) (Grant & Davis, 1997; Lynn, 1986). For an item to be retained, the item’s review needed to result in >80% agreement across experts on content validity, meaning at least seven of the eight reviewers needed to rate both the item’s clarity and relevance as a 3 or 4 (Grant & Davis, 1997; Lynn, 1986). The scientific advisors also provided feedback on technical elements of the measure, suggested additional items or modifications, and commented on the comprehensiveness of addressing SMART and transition readiness. After items that did not meet criteria for retention based on ratings of clarity and relevance were removed, the team met to review the comments and further modify and reduce the item pool. Finally, companion items for the parent report version were developed based on the patient report item pool. Item development for the parent version took place in weekly team meetings, with attention to developing a parent version that reflected their own attributes related to transition readiness as well as their perspectives on their child.

Step 3: Cognitive Interviews and Item Modification

Cognitive interviews involve probing a small group of individuals on their interpretation and understanding of an item, intending to identify problems with the item that result in omission or modification. To identify potential participants for cognitive interviews, we reviewed the schedules and patient summaries of survivorship patients (at least 2 years from end of treatment or 5 years from the date of diagnosis) who attended follow-up care appointments in the Cancer Survivorship Program. We used purposeful sampling (Patton, 2002) to ensure that we tested items across patients/parents with diverse demographic and disease/treatment characteristics, including age (16–19 vs. >20 years old), sex, race/ethnicity (White vs. minority status), time off treatment (less vs. >5 years off treatment), and type of cancer (liquid, solid, or brain tumor diagnosis). Potential subjects were reviewed consecutively and approached if they met the requirements for filling the cells of the various characteristics on which we aimed to select. Participants in the current sample were 21 survivors of pediatric cancer (16–25 years old; 48% male; 89% Caucasian; 59% liquid primary diagnosis) and 23 parents (44–62 years old; 78% mothers; 41% with a bachelors’ and/or professional degree). The institutional review board of the site of the study approved all study procedures. We obtained informed consent from adults (i.e., parents or patients ≥18 years old). For patients who were <18 years old, parents provided consent for the patient, and the patient provided assent. Interviews were completed at the clinic or over the phone.

Participants completed the TRI to get a broad perspective of the content of the measure. Then, they provided feedback on a select group of items via cognitive interviews, which enabled researchers to better understand the thought processes underlying interpretation, information retrieval, and response generation (DeWalt etal., 2007; Irwin, Varni, Yeatts, & DeWalt, 2009). The TRI items were divided into sets of approximately 24 items that included approximately four items from each of the six modifiable SMART components (e.g., knowledge, skills). Grouping items this way resulted in four versions of the cognitive interview for patients, and four parallel versions for parents. The items from the four preexisting SMART components (e.g., demographics, health status) were not included in cognitive interviews to minimize burden and because those items were straightforward items that families would be used to answering (e.g., “How old are you?”; “How is your health insurance provided?”; “How severe are your current medical problems?”).

Participants were interviewed using one of the four sets of TRI items. We designed the purposive sampling plan such that participants with the following characteristics reviewed each set of items: liquid tumor diagnosis, solid tumor diagnosis, <5 years since end of treatment, >5 years since end of treatment, minimal late effects, severe late effects, male, female, adolescent (16–19 years old), young adult (≥20 years old), White, and minority racial/ethnic status. For example, consider that the first participant reviewing one set of items could be a White female teen who finished treatment for leukemia 5 years ago and has minimal late effects. As such, the characteristics of solid tumor, <5 years off treatment, severe late effects, male, young adult, and minority would need to be represented across subsequent participants. The goal was to have a diverse group of subjects, based on our a priori characteristics, review each item set. With regards to the age range, we started with age 16 for eligibility, as this age is when explicit conversations about adult-oriented survivorship care and transition are encouraged (Bashore & Bender, 2016). Patients in our setting are not transferred until their 20s.

Cognitive interviews included both standard probes and item-specific probes (Irwin etal., 2009; Knafl etal., 2007) (Table I). Standard probes included, “In your own words, what do you think this question is asking?” and “How would you change the words to make it more clear?” We also asked a series of item-specific probes to ascertain clarity and relevance of each item. For example, “Can you tell me what you thought of when you read ‘a new health concern’?” and “What does ‘take responsibility’ mean to you?” (Irwin etal., 2009).

Table I.

Cognitive Interview Guide for Sample TRI Item

| TRI Item #16 | How sure are you that you know the names of all your prescribed medications that you take now? |

|---|---|

| 1 = Not at all; 2 = A little; 3 = Somewhat; 4 = Somewhat; 5 = Completely; 6 = I don’t take any medications | |

| Standard probes: | In your own words, what do you think this question is asking? |

| What does this question mean to you? | |

| What did you think of when answering this question? | |

| Was this question easy to understand? | |

| Are there any specific words that are difficult to understand? | |

| How would you change the words to make it clearer? | |

| Was this item hard to answer? If yes, why? | |

| How did you choose your answer? | |

| What do you think about the response choices? | |

| Item-specific probes: | What were you thinking of when you read “prescribed medications”? |

| Would it have been clearer if we had asked, “how confident” instead of “how sure are you”? |

After three initial interviews occurred for an item (and then again after the completion of two more interviews), we sorted feedback by item for patient and parent versions. Study team members discussed the feedback from participants and modified items accordingly. If needed, we also modified item-specific probes to reflect consensus of the feedback and/or assess further issues related to clarity. Subsequently, two additional interviews (a second set) were conducted with the modified items and item-specific probes. Standard probes were not modified to allow consistent collection of data across all items from a set of open-ended questions supported in the literature (Irwin etal., 2009). Several trained interviewers from the study team conducted interviews for each item set to reduce bias of a single interviewer and to increase analytical rigor. In total, each item set was tested in five cognitive interviews with the intended respondent (patient items were tested with patients; parent items were tested with parents).

Results

Step 1 Results: Transition Readiness Concept Specification

As detailed elsewhere (Schwartz etal., 2013), mixed-methods data supported the validity of SMART and additional information was incorporated into the definitions of SMART components as needed. The stakeholders all reported that the SMART components were important and relevant, yet they also differed in what they perceived to be the most important factors, thus supporting the need for multiple reporters in the transition process. Validating SMART was critical for establishing the overall construct and subdomains of TRI.

Step 2 Results: Item Classification and Development: Binning and Winnowing, Item Revisions and Development, and Content Validity Ratings

Literature Review

The review resulted in 37 transition readiness measures that met inclusion criteria. Of the 37 measures, 13 were in peer-reviewed publications and 24 were found on Web sites. Measures included patient report only (n = 19), parent report only (n = 1), provider report only (n = 5), and parent and patient reports (n = 12). Eight measures were disease specific: cystic fibrosis (n = 2), liver disease/transplant (n = 2), kidney transplant (n = 1), spina bifida (n = 1), and sickle cell disease (n = 2). Most used Likert-type response scales (n = 25), and the remaining measures used a checklist or yes/no format (n = 16), multiple choice (n = 4), open-ended (n = 2), or a combination of the above (n = 10). All 37 measures were used for the item development process (Schwartz etal., 2012), which included 1,804 items.

Binning and Winnowing

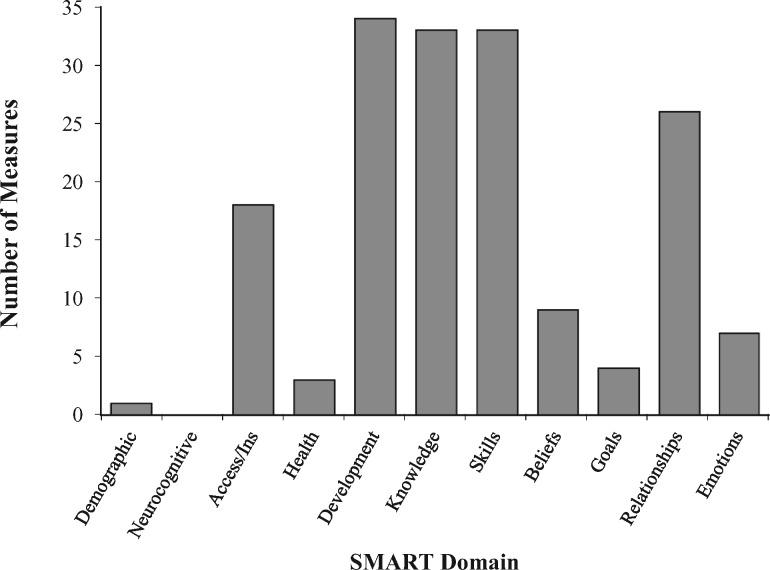

For the binning process, 1,804 items were sorted into the 11 SMART components. To gauge the extent of representativeness of SMART components across extant measures, we graphed the number of measures that had at least one item from each of the SMART domains (Figure 2). Most measures (90%) contained at least one item on developmental maturity, knowledge, and skills/self-efficacy, and 70% of measures also assessed domains of relationships/communication (Figure 2). Notably lacking, however, were measures that incorporated the domains of sociodemographics/culture (3%), neurocognitive functioning/IQ (0%), beliefs/expectations (24%), psychosocial functioning/emotions (19%), and goals/motivations (11%). Thirty-eight percent (n = 684) of the 1,804 identified items were not assigned to a bin or eventually were winnowed because they were related to specific health conditions or treatments (e.g., “What is the proper physiotherapy position?”) or they consisted of the same (or almost the same) item already binned. Thus, we binned 1,120 items across the SMART categories, assigning them to only one bin. Final consensus on binning about SMART domains was: Sociodemographics/Culture (n = 1), Access/Insurance (n = 37), Medical Status/Risk (n = 35), Neurocognitive Functioning/IQ (n = 0), Knowledge (n = 242), Skills/Self-Efficacy (n = 615), Beliefs/Expectations (n = 77), Goals/Motivation (n = 9), Relationships/Communication (n = 73), and Psychosocial functioning/Emotions (n = 31).

Figure 2.

Number of extant transition readiness measures (N = 37) that included at least one item assessing each SMART domain.

It should be noted that during the binning and winnowing process, the decision was made to remove “Developmental Maturity” as a separate category and instead redistribute items across the other bins or eliminate items that were unclear/underspecified (e.g., having developmental maturity to manage disease, being old enough to understand). This is because many items in the Development bin were deemed applicable to other categories after team review (e.g., questions about age related to demographics; questions about maturity applied to skills/self-efficacy, motivation, and so forth). This decision was also made to be consistent with the theoretical validation work of SMART whereby patient, parent, and provider stakeholders deemed Developmental Maturity important, but differed in their interpretation and definition of the construct and felt it was represented by a combination of the other SMART components (Schwartz etal., 2013). Other prior work also supports that development encompasses multiple components (e.g., components related to biology/pubertal status and psychological, cognitive, and social functioning; Holmbeck, 2002). Please note that while most extant measures contained at least one “Development” item, it does not mean that most of the items across measures were “Development” items.

Item Revisions and Development

Following the binning and winnowing process, study team members created additional items to assess SMART components that were not well-represented in other measures, including goals and motivation and objective, preexisting components such as neurocognition/IQ. We also added cancer-specific items to assess medical status and knowledge regarding cancer (e.g., “Did you have a relapse?”). The iterative process of winnowing, revising/combining items, and adding new items resulted in an initial item pool of 160 total items [Sociodemographics/Culture (n = 7), Access/Insurance (n = 3), Medical Status/Risk (n = 3), Neurocognitive Functioning/IQ (n = 1), Knowledge (n = 31), Skills/Self-Efficacy (n = 30), Beliefs/Expectations (n = 16), Goals/Motivation (n = 17), Relationships/Communication (n = 29), and Psychosocial functioning/Emotions (n = 23)]. The number of items differed across the categories given some categories required more items to capture the range of the component as previously defined (e.g., skills/self-efficacy related to managing personal health and transition, communication, adherence, and navigation of the health care system; Schwartz etal. 2013). Because items came from various measures, multiple response-type options were represented, which can pose significant cognitive burden on the participant and difficulty with psychometric evaluation of the measure (DeWalt etal., 2007). Thus, the majority of items were reworked by the multidisciplinary team to use a 5-point Likert-type scale (“How much do you agree…” or “How sure are you…”; 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely) or a frequency Likert-type scale (“How often do you…”; 1 = not at all to 5 = always). A few items used the yes/no response choices (n = 1), a checklist to select the relevant response (e.g., types of academic accommodations; n = 16), or an open-ended response format (n = 5).

Content Validity Ratings

A national scientific advisory committee provided feedback and content validity ratings on the 160 TRI items. Content validity ratings, following the 80% threshold for agreement, revealed 82% of items met criteria for clarity and 93% met criteria for relevance. Items (n = 11) that did not meet the 80% threshold for agreement were removed. Of the TRI items (n = 149) that were retained, the mean clarity rating was 3.66 (range = 3.51–3.71 across SMART components) and mean relevance rating was 3.58 (range = 3.00–3.88 across SMART components) on a scale of 1 to 4. The team also reviewed the comments from the scientific advisors and further modified and reduced the item pool. Several advisors commented that the item pool was too large for a single survey that could be administered in a busy clinic setting (e.g., “need to cut in half at least if possible,” “the full survey should aim for a 15–20 minute duration given the short attention span in this age population”). Further, advisors provided comments on items that indicated the need for further consideration, regardless of content validity scores (e.g., “use this instead of above question,” “not sure if needed”). Thus, to prepare a version of TRI that would be more acceptable and feasible to administer to AYAs in clinical settings, the team used comments from the advisors and collective expertise to collapse and omit items that were not as central to the definitions of the SMART constructs. This resulted in a patient-reported TRI item pool of 109 items.

Companion Item Development

The patient item pool was used to develop the companion parent-report items. For the most part, the parent version has corresponding items to the patient version that report on the parents themselves, or their child, or both. The items of the parent version are not intended to serve as a parent proxy, per se, but to provide parent perspective on items that would reflect corresponding or differing perspectives that may help or hinder the transition process (Schwartz etal., 2011). For example, the parent version asks parents to report on themselves (e.g., “I know the amount (dose) of each medication my child is supposed to take,” “I have talked with my child’s oncology provider about what medical provider he/she will see as an adult for cancer-related follow-up care”), as well as their child (“My child has thought about the transition from a pediatric oncology hospital/provider to an adult one,” “Managing the adult health care system would be easy for my child”). Thus, the parent-report version included more items (n = 115 items) than the patient-report (n = 109 items).

Step 3 Results: Cognitive Interviews and Item Modification

Cognitive Interviews

Ninety-five patient and 103 parent items from the subjective SMART domains were tested in cognitive interviews. Items representing the preexisting SMART components (e.g., demographics) were not subjected to cognitive interviews. After the first set of three interviews per item, we modified 65% of the items based on feedback that the item was difficult to understand, ambiguous, or misinterpreted. Alternative wording was developed, often with phrases used by participants when putting the items in their own words. Common modifications included changes to stems (e.g., many cognitive interview participants preferred “How confident are you…” to “How sure are you…”), response options (e.g., participants suggested adding “don’t know” option for knowledge items, and medical terminology (e.g. the term “healthcare providers” was repeatedly misunderstood as referring to “insurance companies”) to improve clarity. Feedback also informed modification of item-specific questions (probes) for the second set of two interviews.

Items were also omitted. For example, the majority of patients and parents suggested omitting several of the Psychosocial/Emotions items about emotions regarding transferring to an adult provider. Reasons provided for this suggestion included the item (1) did not fit their experience, (2) was difficult to understand, or (3) sounded “awkward.” For example, regarding the item, “When I think about [my child] transferring to an adult provider, I feel proud,” several parents and patients remarked that the descriptor “proud” did not fit their experience. One parent explained, “I am happy that he has grown up, but proud doesn’t seem applicable.” Through discussion and consensus by the multidisciplinary team, incorporating results from the interviews, 28 of 95 (29%) of patient items were removed and 30 of 103 (30%) of parent items were removed.

In almost all categories of the final item pool, some differences exist between patient and parent versions. (See Figure 3 depicting the item totals for each version of TRI). In the items measuring the objective components, parents report on their relationship with the child, whereas only the patients report on personal income, who they live with, and whether they have children. The parent version has 10 more Knowledge items that ask their perspective of their child’s knowledge, in addition to their own knowledge, given findings on deficits in both parent and patient knowledge that would presumably limit motivation to engage in adult follow-up care (Kadan-Lottick etal., 2002; Quillen etal., 2017). Beliefs/Expectations has two additional parent questions reflecting parent perspective on both their and their child’s perceived impact of cultural beliefs on medical decisions, as well as both their and their child’s perceived comfort level with transferring care. Skills/Self-Efficacy has one additional patient question asking the patient about talking about transition to adult care with medical providers. This is consistent with other discrepancies between parent and patient versions in that parents were not asked questions that would reflect the relationship or exchanges between the patient and provider. For example, Goals/Motivation category asks the patient (not parent) about their perspective on their provider’s comfort level with transferring them. Additionally, the Relationship/Communication category asks the patient four additional questions reflecting whether their provider asks their opinion on matters related to their health, as well as three questions reflecting the patient’s comfort level discussing sensitive topics with their provider (sexual health, risk behaviors, disagreement). For the final item pool (see appendix and supplemental material), 14 objective SMART component items (e.g., demographics, treatment history) were added back to the patient version and 12 such items were added back to the parent version. Thus, the patient version has 81 items and the parent version has 85 items.

Figure 3.

Number of items per SMART domain (six subjective domains) in the patient (67 items) and parent versions (73 items) of TRI after the cognitive interviews.

Discussion

The present study described the development of an item pool of a new measure of transition readiness for survivors of childhood cancer. The development of TRI represents the first social-ecological theoretically informed, multi-informant, and content valid item pool to be tested as a measure to inform transition readiness for cancer survivors. To our knowledge, it also represents the first systematic application of NIH PROMIS-endorsed methods for development of a PRO in pediatric psychology, as called for by Forrest and colleagues (2012). We specifically described the detailed and rigorous process to develop the TRI item pool ready for further validation and refinement (Forrest etal., 2012). To date, few transition readiness measures exist that have been validated, and none have closely adhered to the methods endorsed by NIH PROMIS. Thus, this study is not only a contribution to childhood cancer survivorship care in its efforts to develop a survivor transition readiness item pool (ultimately, a validated measure), but it also contributes to the literature on transition readiness assessment development by providing an example of rigorous measurement development that is lacking in the field. The ultimate goal is to use transition readiness assessment to improve the process of transition by identifying modifiable targets of intervention and facilitating continuum of care from pediatrics to adult medicine for childhood cancer survivors.

The results of the current study support the content validity of the TRI item pool, which will be further tested and refined before dissemination for use. The development of TRI, using PROMIS methods, represents an important step in applying the most stringent method of measure development to fill a gap in PROs on transition readiness. Consistent with PROMIS methods, TRI was theoretically informed by SMART (Schwartz etal., 2011; Schwartz etal., 2013), and the SMART domains were used for item pool development. TRI development incorporated feedback from multiple stakeholders and experts via mixed-methods data collection. The process was iterative and purposeful to allow continuous refinement. The feedback and data on the items to date continues to support a social-ecological approach to transition readiness.

Although other transition readiness measures are mostly dominated by a few categories—usually patient skills and knowledge of disease—TRI is the only measure that was derived using a domain-specific approach informed by SMART. By evaluating components such as goals/motivations and expectations/beliefs of AYA survivors, TRI is expected to more comprehensively assess and track transition readiness of AYA survivors from multiple stakeholder perspectives and identify a broad range of modifiable targets of intervention. Such targets of intervention may be based on individual responses (e.g., patient lacks disease management skills) or discrepancies between the parent and child (e.g., parent views patient as less competent or ready than the child; parent and child have differing expectations). Furthermore, unlike existing transition readiness measures, the TRI item pool was informed by multiple stakeholder feedback, which supported its face and content validity of both a patient and parent version.

The present study has several limitations. Although there are many advantages to a measure specifically designed using SMART for AYA childhood cancer survivors, it is also possible that a disease-specific measure may not be readily generalizable for other medical conditions. However, the rigorous methods described in the present study are adaptable for creating disease-specific measures and can inform the adaptation of TRI items for other populations. Second, it is possible that the TRI item pool is not generalizable across AYA childhood cancer survivors owing to differences in practice regarding transition to adult-centered health care. Importantly, there is no current gold standard for transition care as survivors’ age into adulthood. Approximately half of pediatric centers follow their patients indefinitely, with no known strategies for addressing a growing adult survivorship population (Eshelman-Kent etal., 2011). Thus, the TRI will require rigorous psychometric testing across cancer centers to adequately capture the variance of transition readiness attributable to varying transition practices.

It is also important to note that given the iterative and detailed process of using PROMIS-endorsed methods for item pool development, it would be prohibitive for one paper to provide every detail of the process for the TRI item pool development. Further, the rigorous time-consuming process of PROMIS PRO development, especially with a specialized relatively small population like AYA childhood cancer survivors, hinders expedient dissemination of the measure. Our intention was to report on our progress made on a social-ecological approach to transition readiness assessment for childhood cancer survivors, in addition to providing a general overview of our PROMIS-endorsed methods to inform and inspire other rigorous transition readiness measure development or future adaptation of TRI for other disease groups. We encourage others interested in engaging in such rigorous development of PROs to review Forrest and colleagues (2012) detailed description of application of PROMIS methods to pediatric psychology. We also encourage others who are following the PROMIS methodology for transition readiness measure development to use our items in the process of binning and winnowing.

The next phase of TRI development, that will continue to follow PROMIS methods, is a large validation study. Specifically, this will require a large number (100s) of AYA survivors and their parents to complete the TRI and a battery of related transition readiness measures to assess feasibility and psychometrics of the measure (validity, reliability, factor structure), and to calibrate the measure using modern measurement techniques. Calibration is a psychometric process in which the response data from all the respondents are used to develop a scaling of levels of item difficulty and person ability or amount of the latent trait for the entire survey (Reeve etal., 2007). Given the limited number of valid gold standard transition readiness measures to measure construct validity, we will need to not only include measures of transition readiness (e.g., TRAQ) but also measures related to the individual components of SMART that may assess constructs such as self-efficacy, patient/provider trust, and motivation. Ideally, a future large validation study will also entail longitudinal assessment to determine the predictive validity of TRI, including whether TRI predicts adult health care utilization as well as related health care transition outcomes (e.g., overall health/disease control, knowledge, quality of life, and satisfaction with care; Pierce & Wysocki, 2015). Following such analyses using classical and modern measurement techniques, further item modification and omission will take place resulting in the final item bank ready for dissemination and use.

In summary, the present study described the development of the TRI item pool using PROMIS-endorsed PRO measure methodology. Assessing transition readiness based on a social-ecological framework, and from multiple stakeholder perspectives, will provide a more complete assessment of transition readiness, and identify modifiable barriers and facilitators for treatment. Although TRI is not yet finalized, these methods can be applied to the development of other transition readiness measures for other medical conditions and can also serve as an example for other clinicians and researchers interested in the development of other valid PRO measures. Furthermore, the TRI development, involving the establishment of content validity, provides further evidence that transition readiness is complex and multifactorial. Clinical providers should recognize that multiple stakeholder perspectives may influence transition readiness and that many different components may serve as barriers or facilitators. Fortunately, though, the results suggest that many modifiable targets of intervention exist to enhance transition readiness. Thinking “outside the box” beyond patient skills and knowledge will likely be key for the development of future successful transition readiness interventions.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: http://www.jpepsy.oxfordjournals.org/.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the many childhood cancer survivors and their families who participated in addition to the scientific advisory committee who provided feedback.

Funding

This work was supported by grant R21 CA141332, “Transition Readiness of Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer,” awarded by the National Cancer Institute (Dr. Schwartz).

References

- Armstrong G. T., Kawashima T., Leisenring W., Stratton K., Stovall M., Hudson M. M., Sklar C. A., Robison L. L., Oeffinger K. C. (2014). Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashore L., Bender J. (2016). Evaluation of the utility of a transition workbook in preparing adolescent and young adult cancer survivors for transition to adult services: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 33, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz C. L., Telfair J. (2007). Health care transitions: An introduction In Betz C. L., Nehring W. M. (Eds.), Promoting health care transitions for adolescents with special health care needs and disabilities (pp. 3–19). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Cella D., Yount S., Rothrock N., Gershon R., Cook K., Reeve B., Ader D., Fries J. F., Bruce B., Rose M.; PROMIS Cooperative Group. (2007). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care, 45, S3–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children's Oncology Group. (2013). Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers version 4.0. Retrieved from www.survivorshipguidelines.org

- Crowley R., Wolfe I., Lock K., McKee M. (2011). Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 96, 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt D. A., Rothrock N., Yount S., Stone A. A. (2007). Evaluation of item candidates: The PROMIS qualitative item review. Medical Care, 45, S12–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshelman-Kent D., Kinahan K. E., Hobbie W., Landier W., Teal S., Friedman D., Nagarajan R., Freyer D. R. (2011). Cancer survivorship practices, services, and delivery: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) nursing discipline, adolescent/young adult, and late effects committees. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 5, 345–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest C. B., Bevans K. B., Tucker C., Riley A. W., Ravens-Sieberer U., Gardner W., Pajer K. (2012). Commentary: The Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) for children and youth: Application to pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37, 614–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed G. L., Hudson A. J. (2006). Transitioning children with chronic diseases to adult care: Current knowledge, practices, and directions. Journal of Pediatrics, 148, 824–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleland J., Amaral S., Mee L., Blount R. (2012). Getting ready to leave: Transition readiness in adolescent kidney transplant recipients. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37, 85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilleland J., Lee J., Vangile K., Schilling L. H., Record B., Wasilewski-Masker K., Mertens A. C. (2013). Assessment of transition readiness among survivors of childhood cancer. Paper presented at the The National Conference in Pediatric Psychology, New Orleans, LA.

- Grant J. S., Davis L. L. (1997). Selection and use of content experts for instrument development. Research in Nursing and Health, 20, 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson T. O., Friedman D. L., Meadows A. T. (2010). Childhood cancer survivors: Transition to adult-focused risk-based care. Pediatrics, 126, 129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N. (2002). A developmental perspective on adolescent health and illness: An introduction to the special issues. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27, 409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. N., Devine K. A. (2009). Editorial: An author's checklist for measure development and validation manuscripts. J Pediatr Psychol, 34, 691–696. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin D. E., Varni J. W., Yeatts K., DeWalt D. A. (2009). Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 7, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadan-Lottick N., Robison L. L., Gurney J. G., Neglia J. P., Yasui Y., Hayashi R. J., Hudson M., Greenberg M., Mertens A. (2002). Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment. JAMA, 287, 1832–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klassen A. F., Rosenberg‐Yunger Z. R., D'agostino N. M., Cano S. J., Barr R., Syed I., Granek L., Greenberg M. L., Dix D., Nathan P. C. (2015). The development of scales to measure childhood cancer survivors' readiness for transition to long‐term follow‐up care as adults. Health Expectations, 18, 1941–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K., Deatrick J., Gallo A., Holcombe G., Bakitas M., Dixon J., Grey M. (2007). The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Research in Nursing and Health, 30, 224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research, 35, 382–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPheeters M., Davis A. M., Taylor J. L., Brown R. F., Epstein R. A. Jr. (2014). Transition care for children with special health needs. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 900–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulchan S. S., Valenzuela J. M., Crosby L. E., Sang C. D. P. (2016). Applicability of the SMART model of transition readiness for sickle-cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 41, 543–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan P. C., Greenberg M. L., Ness K. K., Hudson M. M., Mertens A. C., Mahoney M. C., Gurney J. G., Donaldson S. S., Leisenring W. M., Robison L. L., Oeffinger K. C. (2008). Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 4401–4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger K. C., Mertens A. C., Sklar C. A., Kawashima T., Hudson M. M., Meadows A. T., Friedman D. L., Marina N., Hobbie W., Kadan-Lottick N. S., Schwartz C L., Leisenring W., Robison L. L.; Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. (2006). Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine C. W., Stollon N. B., Lucas M. S., Brumley L. D., Poole E. S., Peyton T., Grant A. W., Jan S., Trachtenberg S., Zander M., Mamula P., Bonafide C. P., Schwartz L. A. (2014). Barriers and facilitators to successful transition from pediatric to adult inflammatory bowel disease care from the perspectives of providers. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 20, 2083–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. (2002). Purposeful sampling In Patton M. (Ed.), Qualitative research and evaluation methods (pp. 230–246). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. S., Wysocki T. (2015). Topical review: Advancing research on the transition to adult care for type1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40, 1041–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillen J., Li Y., Demski M., Bradley H., Schwartz L., Ginsberg J., Hobbie W. (2017). A matched dyad comparision of parental and survivor knowledge regarding diagnosis, treatment, and future risks: Importance of health literacy and teachable moments. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve B. B., Hays R. D., Bjorner J. B., Cook K. F., Crane P. K., Teresi J. A., Thissen D., Revicki D. A., Weiss D. J., Hambleton R. K., Liu H., Gershon R., Reise S. P., Lai J. S., Cella D.; PROMIS Cooperative Group. (2007). Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Medical Care, 45, S22–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki G. S., Lukens-Bull K., Yin X., Demars N., Huang I., Livingood W., Reiss J., Wood D. (2011). Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: Validation of the TRAQ - Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 160–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L. A., Daniel L. C., Brumley L. D., Barakat L. P., Wesley K. M., Tuchman L. K. (2014). Measures of readiness to transition to adult health care for youth with chronic physical health conditions: A systematic review and recommendations for measurement testing and development. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 588–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L. A., Danzi L., Tuchman L. K., Barakat L., Hobbie W., Ginsberg J. P., Daniel L. C., Kazak A. E., Bevans K., Deatrick J. (2013). Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness to transition to adult care. JAMA Pediatrics, 167, 939–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L. A., Tuchman L. K., Hobbie W., Ginsberg J. P. (2011). A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37, 883–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L. A., Wesley K., Danzi L., Daniel L., Barakat L. P., Bevans K., Deatrick J., Ginsberg J., Hobbie W., Kazak A., Tuchman L. K. (2012). A systematic review of transition readiness measures. Paper presented at the 2012 Conference of the Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine, New Orleans, LA.

- Szalda D., Piece L., Brumley L., Li Y., Schapira M. M., Wasik M., Hobbie W. L., Ginsberg J. P., Schwartz L. A. (2017). Associates of engagement in adult-oriented follow-up care for childhood cancer survivors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 147–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfair J., Alexander L. R., Loosier P. S., Alleman-Velez P. L., Simmons J. (2004). Providers' perspectives and beliefs regarding transition to adult care for adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 15, 443–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood D. L., Sawicki G. S., Miller M. D., Smotherman C., Lukens-Bull K., Livingood W. C., Ferris M., Kraemer D. F. (2014). The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ): Its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Academic Pediatrics, 14, 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.