Abstract

Introduction

Perianal fistulas are a common problem. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment is a new technique for the management of this difficult condition. We describe our initial experience with the technique to facilitate the treatment of established perianal fistulas.

Methods

We reviewed a prospectively maintained database relating to consecutive patients undergoing video-assisted anal fistula treatment in a single unit.

Results

Seventy-eight consecutive patients had their perianal fistulas treated with video-assistance from November 2014 to June 2016. Complete follow-up data were available in 74 patients, with median follow-up of 14 months (interquartile range 7–19 months). There were no complications and all patients were treated as day cases. Most patients had recurrent disease, with 57 (77%) having had previous fistula surgery. At follow-up, 60 (81%) patients reported themselves ‘cured’ (asymptomatic) including 5 patients with Crohn’s disease and one who had undergone 10 previous surgical procedures. Logistical stepwise regression did not demonstrate any statistically significant factors that may have been considered to affect outcome (age, gender, diabetes, previous I&D, Crohn’s disease, smoking, type of fistula).

Conclusions

Our data have shown that video-assisted anal fistula treatment is safe and effective in the management of perianal fistulas in our patients and this suggests it may be applied to all patients regardless of comorbidity, underlying pathology or type of fistula.

Keywords: Proctology, Anal fistula

Introduction

A perianal fistula is an epithelial lined tract that forms a pathological communication between the anal canal or rectum and the skin of the perianal region. Ninety per cent of cases are thought to be cryptoglandular or abscess-related in origin, the remaining being secondary to Crohn’s disease, trauma, malignancy, diverticular disease or radiotherapy.1 It is a common condition, with an estimated incidence of 8.6 per 100,000, predominantly affecting males between 30–50 years of age, with a male to female ratio of 1.8 to 1.2

Established complex perianal fistulas are difficult to treat, with surgical intervention aiming to control sepsis and preserve continence. Commonly used techniques include a one-step fistulotomy if low or fistulectomy with the initial placement of a cutting or loosely fitting drainage Seton, with a view to definitive management at a later date once the patient is sepsis free. These procedures are, however, associated with an unpredictable degree of postoperative sphincter dysfunction.5–8

Efforts to reduce damage to the sphincter complex have resulted in the development of numerous surgical approaches. The use of collagen plugs, fibrin glues and more invasive procedures such as mucosal flap advancement techniques and ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract all aim to avoid muscular injury.9–11 However, success rates in terms of recurrence or postoperative incontinence have been variable.12 First described by Meinero in 2011,13 video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) is an endoscopic, minimally invasive approach for the treatment of complex perianal fistulas. It enables the surgeon to view the fistulous tract directly with minimal trauma to the anal sphincters. This paper briefly describes this new technique and presents a review of a single-centre experience with VAAFT in terms of patient-reported resolution of symptoms and which factors, if any, can be used to predict those patients who will benefit from this relatively new procedure.

Materials and Methods

A prospectively maintained database of consecutive patients undergoing VAAFT since November 2014 was reviewed and data collated for analysis. Data collected included patient demographics, type of fistula (intersphincteric, trans-sphincteric, etc.), comorbidities, smoking status and previous fistula surgery. Patients were clinically assessed for recurrence of symptoms at a planned postoperative review and asked to describe themselves as ‘cured’ or symptomatic. Comparisons were made using Student’s t test with Yates correction (or Fisher’s exact test) for nominal data and log-rank test for nonparametric data. The VAAFT procedure was reviewed by the trust lead for implementation of new surgical techniques on the basis of peer-reviewed literature. As an established alternative treatment for perianal fistulas, it was considered by the trust that ethics committee approval was not required as long as both VAAFT and conventional options were discussed during the preoperative consent process.

VAAFT surgical technique

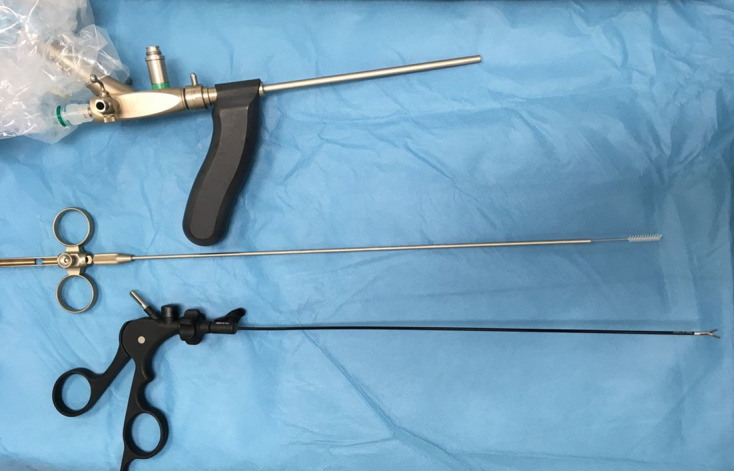

VAAFT is performed using a fistuloscope (Fig 1) manufactured by Karl Storz GmbH, a ball-ended mono-polar electrode, an endobrush and endoscopic forceps. The fistuloscope has an eight-degree angled eyepiece, is equipped with a 3.3 × 4.7 mm twin optical and working channels and has an operative length of 18 cm. Continuous irrigation is provided by glycine–mannitol 1% solution. There are two phases to the procedure: a diagnostic and an operative phase.8

Figure 1.

Fistuloscope (Karl Storz GmbH).

Diagnostic phase

The diagnostic phase delineates the fistulous tract, accurately locates the internal opening and identifies possible secondary tracts or abscess cavities. Circumferentially excising the local scar tissue found at the external opening facilitates insertion of the fistuloscope and liberal use of the irrigation fluid opens up the tract(s) as far as the internal opening. With good endoscopic views of the tract lumen, the surgeon can advance the fistuloscope under direct vision thereby defining the fistula.

Operative phase

Following its delineation, the full length of the fistulous tract is cauterised from within, using the ball-ended monopolar electrode placed down the working channel. Necrotic tissue and/or hair can then be removed with an endobrush or grasping forceps with continuous irrigation ensuring that all waste material is eliminated via the internal opening. Finally, closing the internal opening by fashioning a mucosal advancement flap completes the operation.

Results

Seventy-eight patients were included in our analysis and follow-up data were obtained in 74. Demographic data are presented in Table 1. The median length of follow-up was 14 months (interquartile range, IQR, 7–19 months). At follow-up, 60 patients (81%) reported themselves as ‘cured’ (asymptomatic). The median length of time patients experienced symptoms prior to their first VAAFT was 11 months (IQR 5–17 months). Duration of follow-up was comparable across the symptomatic and the cured groups (P = 0.4). There was no significant difference in the number of patients who reported themselves to be ‘cured’ at follow-up across patients who smoked (P = 0.4), those with diabetes (P = 0.5) or those with Crohn’s disease (P = 0.4). Similarly, there was no difference in the distribution of age between those patients who reported themselves cured and those who were still symptomatic at follow-up (P = 0.9). The gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists grade and type of fistula were also not significant across the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics for those self-reporting as ‘cured’.

| Variable | Patients | P value | |

| (n) | Cured (n) | ||

| Male | 48 | 36 | 0.141 |

| Female | 26 | 23 | |

| ASA grade: | |||

| 1 | 34 | 26 | 0.173 |

| 2 | 35 | 30 | |

| 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | |

| Crohn’s disease | 7 | 5 | 0.435 |

| Diabetes | 7 | 6 | 0.565 |

| Smoking | 12 | 11 | 0.468 |

| Previous procedures: | |||

| 0 | 12 | 7 | 0.652 |

| 1 | 15 | 9 | |

| 2–3 | 21 | 19 | |

| 4–5 | 7 | 5 | |

| > 6 | 6 | 5 | |

| Type of fistula: | |||

| Intersphincteric | 5 | 5 | 0.154 |

| Trans-sphincteric | 63 | 52 | |

| Suprasphincteric | 4 | 2 | |

| Horseshoe | 1 | 1 | |

| Non-anal | 1 | 0 | |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists

Of 3 patients who had diabetes and smoked, two reported themselves as cured at follow-up. Among those seven patients with Crohn’s disease, five reported themselves cured at follow-up after a single VAAFT procedure. Nine patients underwent a second VAAFT and three underwent a third; four and one reported themselves as cured at follow-up, respectively, (Fig 2). VAAFT was carried out as a daycase procedure in all cases with no immediate complications or emergency readmissions in this group of patients.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram.

The majority of the patients had previous surgical interventions prior to VAAFT. The median number of procedures pre-VAAFT was two (IQR 1–4), one individual had ten procedures prior to their VAAFT; this patient self-reported as cured after a single VAAFT. Mucosal rectal advancement flap was performed in every VAAFT as part of the procedure so has not been considered as a variable for analysis. Ten patients had also undergone at least one previous unsuccessful fistulotomy; of these, eight reported themselves cured during follow-up.

When comparing patients who had undergone an examination under anaesthetic and Seton insertion as an index procedure with those patients who had a primary VAAFT, there was no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.803; Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients with Seton prior to video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) compared with no Seton.

| Cured by one VAAFT | Cured by the end of the study | |

| Seton prior to VAAFT (n = 38) | 27 | 31 |

| No Seton prior to VAAFTa (n = 36) | 24 | 29 |

a May have been examined under anaesthesia prior to VAAFT but no active intervention.

Discussion

This single-centre study of prospectively maintained data has shown VAAFT to be safe and effective in the management of perianal fistulas. The procedure can be applied to all patients regardless of comorbidity, underlying pathology or type of fistula present.

Fistulas can be classified into four groups according to the path of the tract: intersphincteric, trans-sphincteric, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric.1 A more commonly used system is to classify fistulas as simple or ‘complex’. Complex fistulas are fistulas that involve more than one-third of the sphincter muscle fibres, have multiple tracts or involve other organs.

Complex fistulas are described as fistulas that traverse the sphincters whose internal opening arises 50% or more of the sphincter length above the anal verge. As a result, sphincter function preservation is a priority after sepsis control. Anorectal sepsis has been shown to be associated with systemic comorbidities such as diabetes, high body mass index and smoking.3–5 Numerous systemic and local factors are thought to affect the rate of healing, although no single aetiology or associated comorbidity has been identified to allow a uniform mode of treatment; hence the myriad of techniques historically and currently employed in the management of perianal fistula.

Our results are slightly lower than those reported by Meinero and Mori, whose one-year healing rate was 87.1%.13 This could be due to patient selection. Even though VAAFT is still offered to all patients as the primary procedure, during the diagnostic phase patients who are found to have abscesses involving the tract, including side branches, have the tract cleaned and diathermy applied without flap reconstruction. A Seton is inserted at this stage and the patient is listed for a repeat procedure in six weeks. Some patients have been found to have a discharging sinus for up to six months prior to reporting resolution of symptoms. This finding has also changed our management strategy with longer postoperative follow-up being offered before further intervention.

Fistula management imposes a financial burden on the NHS. Examination of the clinic visits and surgical interventions of the first 40 patients who underwent VAAFT revealed that 70 scans were performed on our patient cohort prior to VAAFT. These mainly consisted of magnetic resonance imaging, although two patients underwent an endoanal ultrasound and three had urgent computed tomography. A total of 99 operations were performed, of which 24 were as an emergency and most commonly involved an incision and drainage of an abscess, while 75 interventions were elective and usually involved examination under ultrasound (with or without Seton insertion or change). There were 198 outpatient appointments for our patients.

While breaking down the financial burden for our cohort, we estimated the cost of scans to be £13,160; emergency interventions cost £27,432, elective operations £63,225 and outpatient reviews £16,830. The total cost of scans, interventions and clinic appointments was estimated at £7,328 for an individual who had one or two previous procedures prior to VAAFT (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patients undergoing video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) anal fistula management burden and outcomes.

| Pre-VAAFT interventions (n) | Patients (n) | Median scans | Median inpatient stays | ||

| (n) | (range) | (n) | (range) | ||

| 0 | 18 | 1 | 0–2 | 0 | |

| 1–2 | 33 | 1 | 0–4 | 2 | 0–5 |

| 3–4 | 14 | 2 | 0–5 | 5 | 0–9 |

| ≥ 5 | 10 | 5 | 2–10 | 14 | 0–23 |

The findings from this prospective study are encouraging in a difficult group of patients. When treatment options are considered in the complex fistula group, the success of the treatment has to be put into context with the rate of recurrence and reduced continence. Several sphincter-sparing techniques are currently available with variable rates of recurrence and reduced continence. Early data from VAAFT is very promising when the parameters above are considered (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of rates of success, recurrence and reduced continence.

| Procedure | Success rate (%) | Recurrence rate (%) | Reduced continence rate (%) |

| Fistulotomy14–16 | 93–96 | 0–26 | 82 |

| Loose Seton17–19 | 75 | 17 | 26 |

| Cutting Seton20,21 | 98 | 4–8 | 0–63 |

| Fistulectomy22,23 | 67–89 | 5–12 | 0–10 |

| Advancement flap24,25 | 60–93 | 7–33 | 8–31 |

| Fistula plug26,27 | 35–87 | 13–65 | 0 |

| LIFT10,28 | 60–93 | 6–35 | 9 |

| VAAFT | 60–93 | 6–35 | 9 |

The limitations of this study include the potential for single-centre bias, lack of long-term follow-up and lack of objective evidence of sphincter dysfunction or healing (for example, using anal manometry and magnetic resonance imaging, respectively), although it can be debated whether this is necessary if patients report being asymptomatic.

A subgroup analysis comparing outcome to the number of prior operations before VAAFT showed that those who had previous operations, most commonly Setons, did not have a better healing rate. It was hypothesised that the Seton would keep the fistula tract sepsis free. This was not the case in our series, with no significant differences in the groups of patients when comparing those who had a Seton in place or had undergone multiple Seton changes with those patients who had VAAFT as the primary procedure. This finding presents an interesting area for further investigation: should fistulas be initially managed by VAAFT, thereby reducing the morbidity associated with the insertion of a Seton?

In this series, 69% of the patients were symptom free after a single VAAFT. Of the 23 patients who were still symptomatic, only four needed excision of sinuses and in three cases the trans-sphincteric fistula had become superficial and could be laid open. It is unclear as to the mechanism of the superficialisation of a deep fistula tract but this has been seen in other groups of patients including patients who had been treated with Permacol collagen paste and lift procedures.

At the end of the study, 20% of patients were still symptomatic. One possible reason is occult side branches not being identified and cauterised during the operation. The use of hybrid procedures (for example, VAAFT plus LIFT or VAAFT plus Permacol paste) might be a way forward for tackling these fistulas that are ‘non-healers’ despite VAAFT.

At follow-up, patients were simply asked whether they were still symptomatic from their fistula or not. For future consideration, it would be useful to conduct a formal quality of life and continence survey before and after surgery, as well as pain scoring and recovery time post-surgery. Even though reported as minimal by Meinero and Mori in their series, most patients needed significant analgesia at discharge owing to the internal opening being very close to the dentate line and difficulty with raising a mucosal flap due to scarring from previous procedures.13 This finding has also made us look for alternatives to the closure of the internal opening.

We also advocate a change of practice when it comes to managing discharging sinuses (for example following incision and drainage of an acute perianal abscess). We advocate examination under anaesthesia and VAAFT as first-line treatment in this group of patients. The change in practice will reduce the need for magnetic resonance imaging and multiple clinic reviews, thereby reducing the burden on radiology and outpatient clinics.

Conclusions

The study data has shown VAAFT to be safe and effective in the management of perianal fistulas. The procedure can be useful in the management of complex anal fistulas in all patients regardless of comorbidity, underlying pathology or type of fistula present.

References

- 1.Parks A, Gordon P, Hardcastle J. A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1976; (1): 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sainio P. Fistula-in-ano in a defined population. Incidence and epidemiological aspects. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1984; (4): 219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindell T, Fletcher W, Krippaehne W. Anorectal suppurative disease: a retrospective review. Am J Surg 1973; (2): 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D, Yang G, Qiu J et al. Risk factors for anal fistula: a case–control study. Tech Coloproctol 2014; (7): 635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devaraj B, Khabassi S, Cosman B. Recent smoking is a risk factor for anal abscess and fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 2011; (6): 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks C, Ritchie J. Anal fistulae at St Mark's Hospital. Br J Surg 1977; (2): 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Tets W, Kuijpers H. Continence disorders after anal fistulotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; (12): 1,194–1,197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ommer A, Wenger F, Rolfs T, Walz M. Continence disorders after anal surgery: a relevant problem? Int J Colorectal Dis 2008; (11): 1,023–1,031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond T, Porrett T, Scott S et al. Management of idiopathic anal fistula using cross-linked collagen: a prospective phase study. Colorectal Dis 2009; (1): 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong K, Kang S, Kalaskar S, Wexner S. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) to treat anal fistula: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol 2014; (8): 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sileri P, Boehm G, Franceschilli L et al. Collagen matrix injection combined with flap repair for complex anal fistula. Colorectal Dis 2012; : 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narang S, Keogh K, Alam N et al. A systematic review of new treatments for cryptoglandular fistula in ano. Surgeon 2017; (1): 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meinero P, Mori L. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT): a novel sphincter-saving procedure for treating complex anal fistulae. Tech Coloproctol 2011; (4): 417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ratto C, Litta F, Parello A et al. Fistulotomy with end-to-end primary sphincteroplasty for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 2013; (2): 226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arroyo A, Pérez-Legaz J, Moya P et al. Fistulotomy and sphincter reconstruction in the treatment of complex fistula-in-ano. Ann Surg 2012; (5): 935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy H, Zegarra J. Fistulotomy without external sphincter division for high anal fistulae. Br J Surg 1990; (8): 898–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subhas G, Gupta A, Balaraman S et al. Non-cutting Setons for progressive migration of complex fistula tracts: a new spin on an old technique. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011; (6): 793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eitan A, Koliada M, Bickel A. The use of the loose Seton technique as a definitive treatment for recurrent and persistent high trans-sphincteric anal fistulas: a long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; (6): 1,116–1,119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joy H, Williams J. The outcome of surgery for complex anal fistula. Colorectal Dis 2002; (4): 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raslan S, Aladwani M, Alsanea N. Evaluation of the cutting Seton as a method of treatment for perianal fistula. Ann Saudi Med 2016; (3): 210–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton V, Chen C, Lubowski D. Long-term results of the cutting Seton for high anal fistula. A N Z Surg 2015; (10): 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobisch A, Stelzner S, Hellmich G et al. Total fistulectomy with simple closure of the internal opening in the management of complex cryptoglandular fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2012; (7): 750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christiansen J, Ronholt C. Treatment of recurrent high anal fistula by total excision and primary sphincter reconstruction. Int J Colorectal Dis 1995; (4): 207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bondi J, Avdagic J, Karlbom U et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing collagen plug and advancement flap for trans-sphincteric anal fistula. Br J Surg 2017; (9): 1,160–1,166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balciscueta Z, Uribe N, Balciscueta I et al. Rectal advancement flap for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular anal fistulas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017; (5): 599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung W, Kazemi P, Ko D et al. Anal fistula plug and fibrin glue versus conventional treatment in repair of complex anal fistulas. Am J Surg 2009; (5): 604–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ky A, Sylla P, Steinhagen R et al. Collagen fistula plug for the treatment of anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; (6): 838–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanwani A, Nor A, Amri N. Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT): a sphincter-saving technique for fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2010; (1): 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]