Abstract

Purpose

This chapter examines birth outcomes of patients enrolled in Familias Sanas (Healthy Families), an educational intervention designed to reduce health disadvantages of low-income, immigrant Latvia mothers by providing social support during and after pregnancy.

Methodology/approach

Using a randomized control-group design, the project recruited 440 pregnant Latina women, 88% of whom were first generation. Birth outcomes were collected through medical charts and analyzed using regression analysis to evaluate if there were any differences between patients enrolled in Familias Sanas compared to those patients who followed a typical prenatal course.

Findings

Control and intervention groups were found to be similar with regard to demographic characteristics. In addition, we did not observe a decrease in rate of a number of common pregnancy-related complications. Likewise, rates of operative delivery were similar between the two groups as were fetal weight at delivery and use of regional anesthesia at delivery.

Research limitations/implications

The lack of improvements in birth outcomes for this study was perhaps because this social support intervention was not significant enough to override long-standing stressors such as socioeconomic status, poor nutrition, genetics, and other environmental stressors.

Originality/value of chapter

This study was set in an inner-city, urban hospital with a large percentage of patients being of Hispanic descent. The study itself is a randomized controlled clinical trial, and data were collected directly from electronic medical records by physicians.

Keywords: Birth outcomes, social support, intervention, pregnant Latina women

Background

Hispanics/Latinos arc the largest ethnic/racial minority group with more than 50 million people (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Since 2000, Latinos accounted for half or more of the population growth in the nation (US Census Bureau, 2011) with a fertility rate of 2.4 compared to 1.8 for non-Hispanic whites (Passel, Livingston, & Cohn, 2012). Latinos arc also disproportionately represented among the nation's poor; more than 30% or Latinos aged 18 years or younger are living in poverty (Martin, Hamilton, & Ventura, 2011). Thus, Latino individuals, particularly those of Mexican heritage, bear a disproportionate burden of economic disadvantage among Latinos and consequently, carry a disproportional vulnerability to disease, disability, and death associated with preventable health conditions (CDC, 2011). Birth outcomes can impact not only Latinos more disparately than non-Hispanic Whites, but within Hispanic sub-groups, differences in birth outcomes emerge as well. For example, while Cuban women have low infant mortality and preterm birth (Hummer, Eberstein, & Nam, 1992), Mexican women have a higher risk of delivering a preterm and low-weight baby (Singh & Yu, 1996; Zambrana, Scrimshawe, Collins, & Dunkel-Schetter, 1997) and a higher risk of receiving inadequate prenatal care (Frisbic & Song, 2003).

One way to reduce these disparities is through culturally grounded health promotional activities which can influence knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors (Novilla et al., 2006; Padilla & Villalobos, 2006). For Mexican/Mexican American women, offering choices and counseling in health care decisions need to resonate culturally and draw on the strength of culture rather than view culture as a barrier to receiving healthcare (Padilla & Villalobos, 2006). One aspect of Mexican culture that has been shown to significantly influence health outcomes is social support, which embraces the values of familism, respect, and collectiveness (Padilla & Villalobos, 2006). Social support in general has been shown to be a “major factor predicting their excellent birth weight outcomes in spite of very low SES levels” (McDuffie, Beck, Bischoff, Cross, & Orleans, 1996, p. 3).

Given that the importance of prenatal care for maternal and child health is well established (Alexander & Kotelchuck, 2001) and the promotion of medical care can improve pregnancy-related outcomes and potentially reduce societal cost (Cefalo & Moos, 1995), understanding disparities faced by Mexican/Mexican American women is not only an examination of health care access, quality, and utilization, but also a consideration of programs that can encourage, promote, and support better health outcomes for Mexican/Mexican American women.

Barriers to Utilization and Receipt of Care

The unique stressors often faced by Mexican women, particularly for immigrant women, through limited financial resources, cultural beliefs regarding health and illness, lack of social support, and inadequate English language mastery, have been associated with poorer birth outcomes (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006). Utilization of prenatal care is lower for Hispanic women compared to non-Hispanic women, and among Hispanic women, Mexican/Mexican American women utilize less prenatal care than other Hispanic subgroups (Collins & Shay, 1994; Guendelman & English, 1995; Singh & Yu, 1996). The long-term benefits of receiving prenatal care expand past the mother's health to the child's health as well. Hispanic mothers who receive prenatal care not only have better overall health outcomes for the baby (Singh & Yu, 1996; Zambrana et al., 1997) but are also more likely to utilize well-child services including immunizations and well-child visits (Kogan, Alexander, Jack, & Allen, 1998; Moore & Hepworth, 1994; Wiecha & Gann, 1994).

Limited financial resources, living in poverty, and lacking health insurance are key barriers which create disparities in access to and utilization of health care for Mexican/Mexican Americans (Pérez-Escamilla, Garcia, & Song, 2010). Studies consistently report that immigrants, both citizen and noncitizen, are less likely to have and maintain consistent health insurance compared to U.S.-born individuals (Carrasquillo, Carasquillo, & Shea, 2000; Thamer, Richard, Casebeer, & Ray, 1997; Trevino, Moyer, Valdez, & Stroup-Benham, 1991), and even when an immigrant transitions from being undocumented to documented, having health insurance remains significantly less than the general U.S. adult population (Brown, Ojeda, Lara, & Valenzuela, 1999) – 33% in the Latino population compared to 16% in the general US population (McDonald & Hertz, 2008). Lack of health care access is also influenced by limited English proficiency, being foreign-born, and being a noncitizen (DuBard & Gizlice, 2008). Spanish-speaking individuals are less likely to have health insurance, a regular source of care, and utilize preventive medicine compared to English-speaking individuals (DuBard & Gizlice, 2008). While immigrants, in general, are less likely to utilize health care, if insured, immigrants have similar utilization rates as U.S.-born individuals (Siddiqi, Zuberi, & Nguyen, 2009). Latinos arc more likely to have multiple risk factors for the receipt of health insurance and health care utilization, including work status (i.e., having an employer offering health insurance) and residency status (i.e., having access to government-funded health insurance) (Marcelli, 2004). Even when health insurance is present, living in poverty presents the challenge of paying for office visits, prescriptions, and health insurance premiums (Amirehsani, 2010).

Cultural norms and beliefs can influence the perceptions of the importance to seek medical care during and after pregnancy, and the provider-patient relationship can be shaped by cultural assumptions and expectations (Carrillo, Green, & Betancourt, 1999). Cultural beliefs shape the interpretation of the origins of the illness (etiology) and the best methods of healing. These cultural beliefs, if not addressed, can often act as barriers to care (Eshiett & Parry, 2003). Hispanic women receiving prenatal care report concerns about receiving “humanistic care” from providers and other health care professions. Having the personal processes of healthcare (respect, caring, understanding, patience, and dignity), the availability of Spanish-speaking healthcare providers and the inclusion of family members in healthcare decisions were of utmost importance to the women (Berry, 1999; Warda, 2000). Having not only ethnic concordance, but language and gender concordance, can impact the quality of care. Spanish-speaking patients have been found to be at a double disadvantage in encounters with English-speaking monolingual physicians. For example, Hispanic women are more likely to feel embarrassed during medical procedures, particularly if the medical provider is a male (Byrd, Mullen, Selwyn, & Lorimor, 1996) Feeling embarrassed or being ignored can result in less treatment adherence and poorer medical outcomes (Rivadencyra, Elderkin-Thompson Silver, & Waitzkin, 2000). Lack of culturally similar social support networks may also act as a barrier to utilization, particularly for immigrants who have lived in the United States for a longer period of time or for those who art U.S born. Immigrant women, who have lived in the United States longer, tend to become more socially integrated into the host culture and create new social networks to take the place of those in Mexico (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006). As social networks arc replaced and acculturation occurs, women of Mexican heritage adopt poorer health behaviors, particularly during pregnancy (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006). These “Americanized” health behaviors include using substances during pregnancy like cigarettes, alcohol, or illicit drugs (Vega, Kolody, Hwang, Noble, & Porter 1997; Wolff & Portis, 1996) and eating a diet poor in nutrition (Harley, Eskenazi, & BlocK, 2005). These “Americanized” health behaviors have been linked to poorer health outcomes, such as low birth weight and preterm babies, for U.S.-born Mexican American women (Singh & Yu, 1996; Zambrana et al., 1997).

Culturally Grounded Health Promotional Activities

During the past three decades, social support has been cited as having a positive impact on a wide array of health outcomes and behaviors during pregnancy (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006), including increased birth weight (Feldman, Dunkel-Schettcr, Sandman, & Wadhwa, 2000), reduced rates of complications during pregnancy (Norbeck & Anderson, 1989), carlier initiation of prenatal care (Zambrana et al., 1997), higher use of prenatal vitamins (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006), and lower rates of smoking (Schaffer & Lia-Hoagberg, 1997).

Engaging community members in the provision of health education has been identified as an effective strategy to provide social support and bridge the cultural gap between providers and patients. These community members, often called promotoras de salud (health promoters), live in the communities they serve, distribute health information, encourage utilization of health care services, and reinforce Mexican cultural practices and beliefs (Larkey, 2006; McGladc, Saha, & Dahlstrom, 2004; Ramos, May, & Ramos, 2001). This approach has been successfully used in the Latino community through the engagement of paraprofessional women from the community (Hunter et al., 2004; Larkey, 2006) to have a positive impact on utilization, access, and overall health outcomes (Hunter et al., 2004; Larkey, 2006).

The focus of this study is to examine birth outcomes of patients enrolled in Familias Sanas (Healthy Families), an educational intervention designed to reduce health disadvantages or low-income, immigrant Latina mothers by providing social support during and after pregnancy. The original study sought to determine if participants enrolled in the intervention utilized the postpartum visit at rates higher than those seen in the control group (Marsiglia, Bermudez-Parsai, & Coonrod, 2010). This secondary study seeks to evaluate birth outcomes in the intervention and control groups with the intent to determine if improved outcomes were seen in the group receiving social support.

Familias Sanas sought to empower women to take an active part in the management of their health by encouraging them to advocate for themselves. In partnership with Women's Care Clinic at Maricopa Integrated Health Systems, the overall aim of Familias Sanas was to increase Latina mothers' access to and utilization of interconception care as a means of enhancing the overall well-being of the mothers and their children. In addition to visiting with a health care professional, the patient met with a prenatal partner during each clinic visit of the pregnancy at the Women's Care Clinic at Maricopa Integrated Health Systems, a prenatal clinic located at a major urban hospital in the Southwest United States. Prenatal partners used this opportunity to establish rapport with the patient. In the following meetings the prenatal partner provided education on prenatal care, discussed the patient's concerns, and developed a plan for regular prenatal and postpartum visits. Participants in the intervention group met with prenatal partners from 1 to 20 times, from the time of recruitment to the time they delivered their babies.

Familias Sanas took a one-on-one approach connecting Latino patients to Latino female professional health educators that served as prenatal partners. Prenatal partners were Master Level students, bilingual and bicultural, and highly experienced and committed to work with the Latino population. These partners provided basic health education, translating (culturally as well as linguistically) and reinforcing the medical advice provided to pregnant women by the health care professionals. They also worked with the patient to identify barriers to care and possible solutions, building on existing cultural assets and empowering patients to utilize those assets. Prenatal partners helped women navigate the health care system and empower them to advocate for themselves. The education component of Familias Sanas was based on a book that the clinic distributed among all pregnant women that sought medical services at the Clinic: “Hola Bebe.” This book is divided in chapters that contribute casy-to-read information about each month of a woman's pregnancy and including things they could do to increase the likelihood of experiencing a healthy pregnancy (e.g., taking folic acid, attending medical appointments), and how to get ready for the birth of the baby. The book is beautifully illustrated and appealing, even to mothers with low literacy levels. The Familias Sanas team prepared five minute summaries of each chapter, and utilized the book illustrations to put together a short curriculum that was used as the educational piece. In addition, the Familias Sanas team focused on support and empowerment. During the educational sessions, prenatal partners encouraged women to discuss/share any issues related to their pregnancies and to medical care. When women shared concerns or had questions, prenatal partners helped them brainstorm ways to ask those questions from their health care providers. Patients were empowered to go back to the health care provider for clarifications and/or answers to their questions.

Methods

Using a randomized control-group design, the project recruited 440 pregnant Latina women attending the Women's Care Clinic at Maricopa Integrated Health Systems, a hospital providing services to a low-income, prisoner, or immigration-detainee populations who arc mostly receiving Medicaid/Medicarc insurance. In order to participate, women needed to (1) self-identify as Latina/Hispanic, (2) be 18 years of age or older, and (3) be less than 35-wecks pregnant. Patients meeting the inclusion criteria were recruited for the study during their first clinic visit between December 1, 2007 and April 30, 2009. The 440 participants were near evenly distributed between the two conditions (intervention N = 221; control N = 219). Sealed envelopes with the group assignment (treatment or control) and with accompanying baseline assessment instruments were maintained at the clinic. Each patient in the treatment condition received the intervention from her first clinic visit (i.e., recruitment into the study) until birth and was followed for two months after birth with prenatal partners (as described above). Each patient in the control condition received care as usual. Control group participants were recruited into the study during their first clinic visit and were followed until two months after birth.

Sample

The vast majority of women were of Mexican origin (81%) and first generation (88%) with a mean age of 27 (SD=5.95) The average annual income was $15,792, with 78% of womcn reporting annual incomes of less than $20,000. While 68% of women reported less than a high school degree, one quarter (25%) had completed less than six years of schooling.

Data Collection

Upon enrollment, participants completed a baseline survey which asked questions about acculturation, social support, stress, and demographics. To obtain medical outcomes for the participants and babies, electronic medical charts were reviewed to collect information about the following variables: age, gravity and parity, length of hospital stay, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, maternal medical complication of diabetes, hypertension, Preeclampsia, post-partum fever, hemorrhage, route of delivery, induction of labor, use of epidural, and whether or not the patient planned to breastfeed after delivery. The chart review was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Maricopa Medical Center prior to data extraction. This information was found in the scanned archives of the medical record, including the standard history forms, the delivery note, the admission history and physical examination, the discharge summary, and nursing delivery notes. Data were collected by healthcare providers familiar with the delivering facility and the record-keeping system. In total, out of the 440 patients enrolled in the study, we were able to collect complete data on 356 of the participants with 169 in the control group and 187 in the intervention group. Outcome data were not available on 84 of the initially enrolled patients for a variety of reasons including transfer of care, delivery outside of our hospital system, and loss of pregnancy prior to term. We did not collect delivery information on patients that did not deliver at Maricopa Medical Center.

Measures

Medical outcome measures were collected on both the baby and the mother. Gestational age is measured as the age of the fetus at the time of birth with a full-term gestational age equal to 40 weeks, though average gestational age ranges between 38 and 42 weeks. Birth weight of the baby is measured in grams, with an average full-term baby weighing between 2700 and 4000 grams. Length of stay in the hospital measured, in days, the total days from admission to discharge. Anesthesia was measured by use of an epidural during delivery. Induction refers to if the labor was induced. Delivery route refers to delivery of the baby through a vaginal delivery, a cesarean section (C Section), or an operative vaginal delivery (vaginal delivery through use of forceps or vacuum). Numerous maternal complication data were collected including the presence of gestational hypertension (GHNT), chronic hypertension (CHNT), preeclampsia (PreEcc), gestational diabetes (GDM), diabetes prior to pregnancy (PreDM), postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), and maternal postpartum fever (Fever). Data were reviewed using regression analysis to evaluate if there was any difference in birth or delivery outcomes of the patients who had a prenatal partner compared to those patients who followed a typical prenatal course.

Results

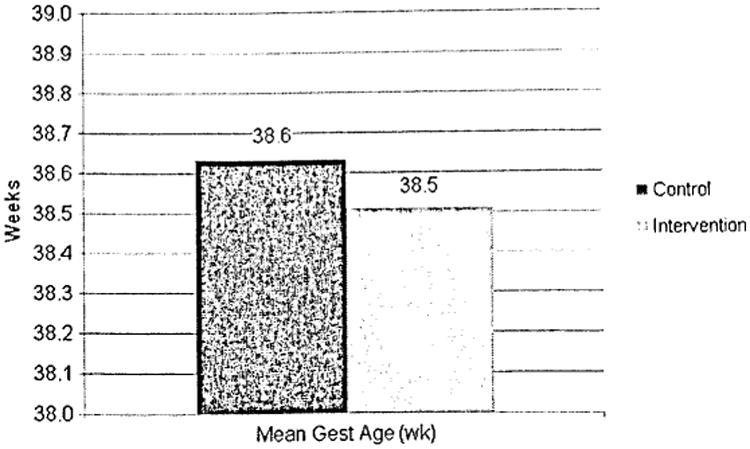

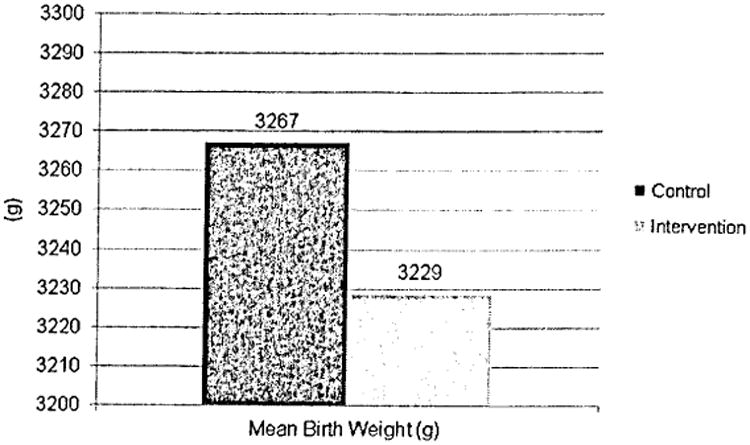

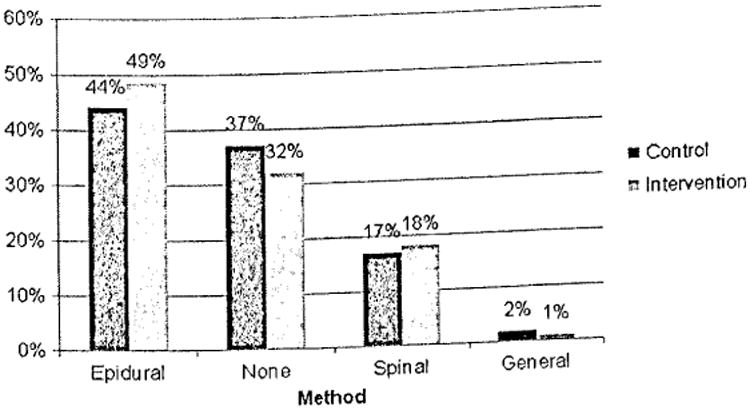

Control and intervention groups were found to be similar with regard to demographic characteristics. The mean age of the participants was 26 in the control and 27 in the intervention group. Mean gravidity and parity were the same with mean gravidity of 3 and mean parity of 2. The mean gestational age at delivery was 38.5 weeks for the control group and 38.6 weeks for the intervention and intervention group (Fig. 1). Mean birth weights were 3,267 grams and 3,229 grams for the control and the intervention group, respectively (Fig. 2). Length of the hospital stay postdelivery was an average of 3.3 days for the control group and 3.6 for the intervention patients (Fig. 3). When investigating the mode of anesthesia, 44% of control participants utilized epidural compared to 49% of the intervention group. The percentage of patients who used no anesthesia was 37% and 32%, respectively; a spinal (typically used with cesarean section) was utilized 17% in the control and 18% in the intervention and general anesthesia which is used in an emergency setting was 2% and 1 %, respectively (Fig. 4). None of these findings were found to be statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Gestational Age.

Fig. 2.

Birth Weight.

Fig. 3.

Length of Stay.

Fig. 4.

Anesthesia.

Maternal medical complications occurred with similar frequency in the control and intervention groups. There was no statistically significant difference in outcomes of hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, postpartum hemorrhage, and maternal fever (Fig. 5). Likewise, induction rates were similar between the intervention and control groups at 15.5% and 17%, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Induction and Maternal Complication Data.

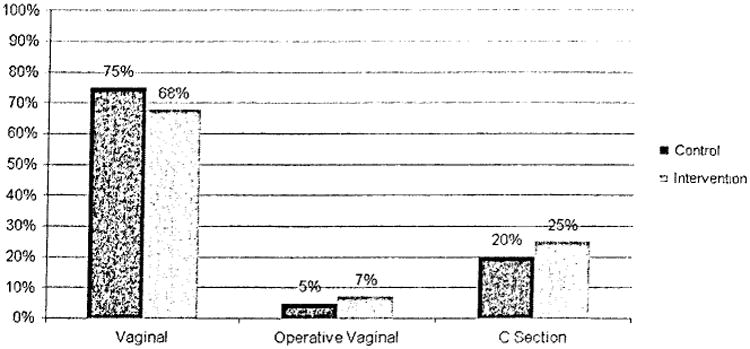

Delivery route was also investigated. The number of patients with spontaneous vaginal delivery was 75% in the control compared to 68% in the intervention group. Operative vaginal delivery, comprising both forceps and vacuum deliveries occurred 5% and 7%, respectively. A cesarean section totaled 20% of the patients in the control group and 25% in the intervention group (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Delivery Route.

Conclusions

Families Sanas was originally designed to evaluate if pairing prenatal care patients with a Prenatal Partner/Promotora would increase compliance with the postpartum visit. In the primary study, patients in the intervention group did have a higher rate of postpartum follow up than a control group of patients who did not have contact with the prenatal partner during the course of prenatal care (Marsiglia et al., 2010). This study was a secondary analysis of the aforementioned study which aimed to determine if patients in the intervention group experienced improved birth outcomes compared to patients who did not have contact with a prenatal partner. We did not observe a decrease in rate of a number of common pregnancy-related complications. Likewise, rates of operative delivery were similar between the two groups as were fetal weight at delivery and use of regional anesthesia at delivery.

One of the greatest strengths of this study is that it was a randomized controlled clinical trial. The control and intervention groups were found to be similar in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics. Furthermore, the outcome information was obtained directly from electronic medical records by physicians familiar with collecting the clinical data assessed. Therefore the outcome data arc felt to be detailed and accurate. The study was performed at an inner-city, urban hospital with a large percentage of patients being of Hispanic descent. This allowed for relatively easy recruitment of patients from this often under-studied population.

However, significant differences were not seen in birth outcomes between the women intervention and control groups. This could be explained by the fact that there were a large number of patients for whom delivery information was not available. Although there was a large number initially recruited, nearly one quarter of enrolled patients did not have data available to collect – meaning they either delivered elsewhere or had a miscarriage. Additionally, this is a secondary analysis of a prior study. The original study was designed to investigate compliance with postpartum follow-up visit; improvement in birth outcomes was not a goal targeted in the study design. It could be that there was more emphasis on the postpartum follow-up and less on prenatal care, or that the study was not tailored to the goal of altering delivery outcomes. Since there was a statistical difference in the number of patients returning for postpartum follow up in the original study, one could postulate those same patients will be more likely to continue to receive well-woman visits for themselves in the future. As noted previously, Hispanic mothers who receive prenatal care have better health outcomes for baby and are more likely to utilize well-child visits and have their children immunized (Kogan et al., 1998; Moore & Hepworth, 1994; Singh & Yu, 1996; Wiecha & Gann, 1994; Zambrana et al., 1997). It may be that women who were encouraged to present for the postpartum visit will be more likely to continue to access healthcare services for their children although this outcome was unfortunately not assessed in this secondary outcome study. Women enrolled in the intervention were better able to deal with complications, have improved mental health or exhibit a decrease in postpartum depression, although again this secondary analysis did not examine these outcomes. Decreased postpartum depression has been seen in low-income women with improved quality of social support (Collins, Dunkel-Schetter, Lobel & Scrimshaw, 1993).

One final explanation for the lack of improvement in birth outcomes for this study may be that this social support intervention was not significant enough to override long-standing stressors such as socioeconomic status, poor nutrition, genetics, and other environmental stressors (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006; Pércz-Escamilla, Garcia, & Song, 2010). In the initial study patients were eligible to participate if they presented for prenatal care at less than 34 weeks gestation – relatively late in pregnancy. Some of the documented benefits of culturally grounded health promotional activities include increased birth weight (Feldman et al., 2000), earlier initiation of prenatal care (Zambrana et al., 1997), higher use of prenatal vitamins (Harley & Eskenazi, 2006), and lower rates of smoking (Schaffcr & Lia-Hoagberg, 1997). It is likely that many of the patients assessed in this study were admitted to the intervention too late in pregnancy to see measurable health benefits by the time of delivery. Many of the obstetric complications which were evaluated in the secondary analysis, in particular preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, are felt to be established early in the pregnancy or even prior to pregnancy, making it less likely that an intervention begun at entry into prenatal care would have a measurable clinical benefit.

There are many factors that affect the health of a pregnancy including preconception health of the patient, genetics, socioeconomics, and prior birth history. While it is has been demonstrated that Mexican women have a higher risk of delivering a preterm and low-weight baby (Singh & Yu, 1996; Zambrana et al., 1997), the exact mechanisms at play are still unknown. For Mexican women, when compared to other Mexican women, the role of social support may not have as significant of a role as these other factors. Social support is an important part of women's lives; however, it is unclear if it has any role in improving birth outcomes in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Hispanic Health Services Grant Program/Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, award 1H0CMS03207. It was hosted by the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, an exploratory center of excellence on minority health and health disparities research funded by award P20MD002316 of the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alexander GR, Kotelchuek M. Assessing the role and effectiveness of prenatal care: History, challenges, and directions for future research. Public Health Report. 2001;116(4):306–316. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50052-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirehsani KA. Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes in an emerging latino community: Evaluation of health disparity factors and interventions. Home Health Care Management Practice. 2010;22:470–478. [Google Scholar]

- Berry AB. Mexican American women's expressions of the meaning of culturally congruent prenatal care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 1999;10(3):203–212. doi: 10.1177/104365969901000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ER, Ojeda VD, Lara LM, Valenzuela A. undocumented immigrants Changes in health insurance coverage with legalized immigration status. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd TL, Mullen PD, Selwyn BJ, Lorimor R. Initiation of prenatal care by low-income Hispanic women in Houston. Public Health Reports. 1996;111(6):536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O, Carasquillo A, Shea S. Health insurance coverage of immigrants living in the United States: Differences by citizenship status and country of origin. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:917–923. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo JE, Green AR, Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural primary care. A patient- based approach. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;130:829–834. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cefalo RC, Moos MK. Preconceptional health care: A practical guide. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Health disparities and inequalities report – Center 2011 Morbidity and mortality weekly report,supplement. Vol. 60. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Collins J, Shay D. Prevalence of low birth weight among Hispanic infants with United States-born and foreign-born mothers: the effect of urban poverty. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1994;139(2):184–192. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lobel M, Scrimshaw SC. Social support in pregnancy: Psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:1243–1258. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBard CA, Gizlice Z. Language spoken and differences in health status, access to care, and receipt of preventive services among US Hispanics. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(11):2021–2028. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshiett MU, Parry EH. Migrants and health: A cultural dilemma clinical Medicine. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians. 2003;3(3):229–231. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.3-3-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(5):715–725. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbie WP, Song SE. Hispanic pregnancy outcomes: Differentials over time and current risk factor effects. Policy Studies Journal. 2003;31(2):237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S, English P. Effect of United States residence on birth outcomes among Mexican immigrants: an exploratory study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142(9):S30–S38. doi: 10.1093/aje/142.supplement_9.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley K, Eskenazi B. Time in the United Slates, social support and health behaviors during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(2006):3048–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley K, Eskenazi B, Block G. The association of time in the US and diet during pregnancy in low-income women of Mexican descent. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2005;19(2):125–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Eberstein IW, Nam C. Infant mortality differentials among hispanic groups in Florida. Social Forces. 1992;70:1055–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JB, de Zapien JG, Papenfuss M, Fernandez ML, Meister J, Giuliano AR. The impact of a promotora on increasing routine chronic disease prevention among women aged 40 and older at the US-Mexico border. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(4 suppl):18S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan M, Alexander C, Jack B, Allen M. The association between adequacy of prenatal care utilization and subsequent pediatric care utilization in the United States. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1):25–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkey L. Las mujeres saludables: Reaching Latinas for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer prevention and screening. Journal of community health. 2006;31(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-8190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelli EA. The unauthorized residency status myth: Health insurance coverage and medical care use among Mexican immigrants in California. Migraciones Internacionales. 2004;2(4):5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Bermudez-Parsai M, Coonrod D. Familias sanas: An intervention designed to increase rates of postpartum visits among Latinas. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21:119–131. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: Final data for 2009 National vital statistics reports. 1. Vol. 60. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie R, Beck A, Bischoff K, Cross J, Orleans M. Effect of frequency of Prenatal care visits on perinatal outcome among low-risk women. JAMA. 1996;275:847–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald M, Hertz Rp. A profile of uninsured persons in the United States. Pfizer Facts. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.pfizer.com/filcs/products/Profile_of_uninsured_persons_in_the_United_States.pdf.

- McGlade MS, Saha S, Dahlstrom ME. The Latina paradox: An opportunity for restructuring prenatal care delivery. Journal Information. 2004;94(12) doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore P, Hepworth J. Use of perinatal and infant health services by Mexican-American medicaid enrollees. JAMA. 1994;272(4):297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbeck JS, Anderson NJ. Psychosocial predictors of pregnancy outcomes in low-income Black, Hispanic, and White women. Nursing Research. 1989;38(4):204–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novilla M, Lelinneth B, Barnes MD, De La Cruz NG, Williams PN, Rogers J. Public health perspectives on the family. Family & Community Health. 2006;29(1):28–42. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla YC, Villalobos G. Cultural responses to health among Mexican American women and their families. Family & Community Health. 2006;30(1S):S24–S33. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel J, Livingston G, Cohn D. Explaining why minority births now outnumber White births. [Accessed on January 20, 2012];Pew Research Social & Demographic Trends. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/20l2/05/l7/explaining-why-minority-births-now-outnumber-white-births/

- Pérez-Escamilla R, Garcia J, Song D. Health care access among Hispanic immigrants: ¿Alguien está escuchando? [Is anybody listening?] NAPA Bulletin. 2010;34:47–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4797.2010.01051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos IN, May M, Ramos KS. Field action report. Environmental health training of promotoras in colonias along the Texas-Mexico border. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;4(91):4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.4.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivadeneyra R, Elderkin-Thompson V, Silver RC, Waitzkin H. Patient centeredness in medical encounters requiring an interpreter. The American Journal of Medicine. 2000;108(6):470–474. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer MA, Lia-Hoagberg B. Effects of social support on prenatal care and health behaviors of low-income women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1997;26(4):433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi A, Zuberi D, Nguyen QC. The role of health insurance in explaining immigrant versus non-immigrant disparities in access to health care: Comparing the United States to Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(10):1452–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Yu S. Adverse pregnancy outcomes: Differences between US and foreign-t born women in major US racial and ethnic groups. American Journal of public Health. 1996;86(6):837–843. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.6.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thamer M, Richard C, Casebeer AW, Ray NF. Health insurance coverage among foreign-born US residents: The impact of race, ethnicity, and length of residence. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevino FM, Moyer ME, Valdez RB, Stroup-Bcnham CA. Health insurance coverage and utilization of services by Mexican Americans, mainland Puerto Ricans and Cuban Americans. JAMA. 1991;265:233–237. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460020087034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 131. Washington, DC: 2011. Statistical abstract of the Untied States: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compenindia/statab/ [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Kolody B, Hwang J, Noble A, Porter PA. Perinatal drug use among immigrant and native-born Latinas. Substance Use & Misuse. 1997;32(1):43–62. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warda MR. Mexican Americans' perceptions of culturally competent care. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2000;22(2):203–224. doi: 10.1177/01939450022044368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiecha J, Gann P. Does maternal prenatal care use predict infant immunization delay? Family Medicine. 1994;26(3):172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff CB, Portis M. Smoking, acculturation, and pregnancy outcome among Mexican Americans. Health Care for Women International. 1996;17(6):563–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrana RE, Scrimshawe SC, Collins N, Dunkel-Schetter C. Prenatal health behaviors and psychological risk factors in pregnant women of Mexican origin. The role of acculturation. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(6):1022–1026. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]