Abstract

Background/Aims

The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act mandates that applicable clinical trials report basic summary results to the ClinicalTrials.gov database within one-year of trial completion or termination. We aimed to determine the proportion of pulmonary trials reporting basic summary results to ClinicalTrials.gov and assess factors associated with reporting.

Methods

We identified pulmonary clinical trials subject to the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (called highly likely applicable clinical trials [HLACTs]) that were completed or terminated between 2008–2012 and reported results by September 2013. We estimated the cumulative percentage of applicable clinical trials reporting results by pulmonary disease category. Multivariable Cox regression modeling identified characteristics independently associated with results reporting.

Results

Of 1,450 pulmonary HLACTs, 380 (26%) examined respiratory neoplasms, 238 (16%) asthma, 175 (12%) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 657 (45%) other respiratory diseases. Most (75%) were pharmaceutical HLACTs and 71% were industry-funded. Approximately 15% of HLACTs reported results within one-year of trial completion, while 55% reported results over the five-year study period. Earlier phase HLACTs were less likely to report results compared to phase 4 HLACTs (phases 1/2, 2 (adj HR 0.41 [95% CI: 0.31–0.54]); phase 2/3 and 3 (adj HR 0.55 [95% CI: 0.42–0.72]); phase N/A (adj HR 0.43 [95% CI: 0.29–0.63]). Pulmonary HLACTs without Food and Drug Administration oversight were less likely to report results compared with those with oversight (adj HR 0.65 [95% CI: 0.51–0.83]).

Conclusions

15% of pulmonary clinical HLACTs report basic summary results to ClinicalTrial.gov within one year of trial completion. Strategies to improve reporting are needed within the pulmonary community.

Keywords: Policy, Clinicaltrials.gov, The Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act, pulmonary, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, transparency, compliance, clinical trials

Background/Aims

As of January 2017, National Institutes of Health has mandated that all clinical studies with more than one human subject and receiving partial or complete NIH funding, report basic summary results to the ClinicalTrials.gov database within one year of completion or termination. Failure to comply can result in penalties such as loss of funding and a $10,000 fine per day of noncompliance.1, 2 The National Institutes of Health policy will cover all forms of biomedical and health-related outcome research including interventional, observational, and feasibility studies. The National Institutes of Health policy is an extension of the 2007 Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act that mandated that “applicable clinical trials” report basic summary results (i.e., participant flow, baseline characteristics, outcomes measures and adverse events) to the database, within one year of trial completion or termination.3–5 “Applicable Clinical Trials” were limited to all non-phase I interventional studies evaluating biologics, drugs, or devices, with at least one study site in the United States, or investigational drug or device trials.6, 7

Public reporting of clinical trial results promotes transparency in clinical research.3, 6, 8–11 In 2000, the ClinicalTrials.gov database was created as a registry of interventional trials. In 2007, mandatory reporting was introduced to reduce reporting and publication bias, promote efficient allocation of research dollars, and to fulfill the ethical obligation to use clinical research results to contribute to our field of knowledge.4, 11–15 A recent study noted that only 13.4% of all applicable clinical trials completed between 2008 through 2012 reported results within one year of completion or termination while 38.3% reported results any time during the five-year study period.16 Nguyen et al. found that 9% of phase II or IV cancer drug trials from 2007–2010 reported results within one year and 31% within 3 years.17, 18 However, the extent to which pulmonary applicable clinical trials report summary results is currently unknown.19

We sought to determine the proportion of applicable clinical trials in pulmonary medicine reporting basic summary results to the ClinicalTrials.gov database and assess factors independently associated with results reporting to inform future implementation strategies.

Methods

Data sources

We identified pulmonary trials likely subject to the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act, called highly likely applicable clinical trials (HLACTs), using an algorithm based on input from the National Library of Medicine.16 The details of the HLACT algorithm were previously reported, and the algorithm steps are outlined in supplement Table E1.16 In brief, we included all registered trials (n=152,611) between January 1, 2008 and September 27, 2013. We excluded trials that did not meet criteria for an applicable clinical trial.16, 20 Additionally, we excluded trials with a “withdrawn” status (i.e. study stopped prior to enrollment of first participant) or a completion date prior to December 2007, which was before enactment of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act. After exclusions, 32,656 clinical trials were identified as HLACTs. We further restricted analysis to HLACTs that were completed or terminated between January 1, 2008 and August 31, 2012 to allow an opportunity to report within one year of study end date.

Validation of HLACT algorithm

Anderson et al.16 confirmed the accuracy of the HLACT algorithm by manually reviewing a random sample of 205 HLACTs and 100 non-HLACTs at high risk for being misclassified. They published the details of their manual review in their original manuscript and the corresponding online supplement. In brief, two reviewers (MA, RC) independently reviewed a sample of HLACT and non-HLACT trials to determine if they were applicable clinical trials and required to report results. Based on the experience of ClinicalTrials.gov staff reviewing the accuracy of trial registration records, Anderson et al. learned that trials at highest risk for being misclassified as a non-HLACTs are those that incorrectly reported that their study did not involve an FDA-regulated intervention type.16 (Personal communication, Dr. Zarin, 10/10/2014). So Anderson et al. sampled trials not identified as HLACTs, targeting studies that did not list their intervention as a drug, device, biologic, genetic or radiation. During manual review, they determined whether these studies did actually use an FDA-regulated medical product.

The methods for evaluating trials for HLACT status were confirmed by Dr. Deborah Zarin and Tony Tse at ClincialTrials.gov. Discrepancies were resolved by group consensus. Of the 205 HLACTs, they found 2 that were not applicable clinical trials and estimated that 4–9 were probably not HLACTs. Of the 100 non-HLACTs, 16–19 trials were actually HLACTs due to the trial sponsors not correctly identifying the intervention type.

Anderson et al. also determined the number of HLACTs that were not legally required to report results. A study sponsor could delay the 12-month deadline for results reporting for several reasons including submitting a “certification of initial use” if the medication product was not approved for market; “certification of new use” if the sponsor intended to see approval of a new use of an approved product; or an extension to delay result for a good cause. Data on trials that submitted certification or extension requests to ClinicalTrials.gov was provided by the National Library of Medicine. These trials are still considered applicable clinical trials, therefore correctly identified by the algorithm, but are not legally required to report results because they submitted a certificate or extension request.16

Identification of pulmonary HLACTs

To identify pulmonary HLACTs, we used medical subject headings terms, which are annotations generated by the National Library of Medicine or study personnel. Pulmonary terms were categorized under the major medical subject headings tree heading of ‘respiratory tract diseases’, and a study was included if at least one medical subject headings term was a respiratory tract disease found in the conditions provided by study personnel or in medical subject headings annotations generated by the National Library of Medicine (online supplement Table E2).21 A pulmonologist (ILR) reviewed terms for relevance and categorized into disease categories, including respiratory neoplasm, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other (online supplement Table E3). Categorization of medical subject headings terms was confirmed by a second pulmonologist (LQ). For HLACTs with more than one pulmonary condition identified, we categorized each study into mutually exclusive categories to minimize overlap of conditions according to the following hierarchical order: respiratory neoplasm, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other.

Characterizing clinical HLACTs

We characterized HLACTs according to their primary purpose, intervention group (i.e., biologic, drug, device, other), phase, Food and Drug Administration oversight authority, funding source, enrollment size, recruitment status, study duration, year of study completion, number of arms, presence of randomization, presence of masking and disease group (i.e., neoplasm, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, other).7, 16, 22, 23 Table E4 in the online supplement contains additional descriptions of trial characteristics.

Outcomes

Our principal outcomes were occurrence of HLACTs summary results being reported in ClinicalTrials.gov within one-year of HLACT completion or termination, and time to reporting of HLACT summary results during our five-year observation period (January 1, 2008 to September 27, 2013). In accordance with the Federal Drug Administration and Amendment Act, we considered HLACTs to have reported results if they recorded at least one basic summary result in the database. According to the Federal Drug Administration Amendment Act, reporting results in a peer-reviewed journal is not considered fulfillment of federal results reporting requirements. We defined a HLACT’s time to reporting results as the number of months between the HLACT’s primary completion date or termination date and the date HLACT results were first uploaded into the database.16

Statistical analysis

We described HLACTs according to disease categories. We used Kaplan-Meier curves to estimate cumulative percentage of HLACTs reporting results within one-year and five-years. We stratified Kaplan-Meier curves by disease category. We compared disease category Kaplan-Meier curves using log-rank test. We constructed multivariable Cox regression models to identify factors independently associated with reporting results. We constructed models that contained phase, oversight, funding source, enrollment, disease group, primary purpose, intervention group, HLACTs status (i.e., completed or terminated), study duration, number of arms, use of randomization, masking, and primary completion year. All p-values were two sided. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons. An aim of this study was to evaluate whether there were time trends in the reporting of results to ClinicalTrials.gov for pulmonary trials, and whether these trends were similar across disease groups. To address this aim we performed interaction testing to evaluate the relationship between disease group and study completion year. Of factors included in the Cox regression model, only total enrollment had missing values with 1.2% missing. We excluded missing values from the analysis. All analyses were performed at Duke Clinical Research Institute using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Pulmonary HLACT characteristics

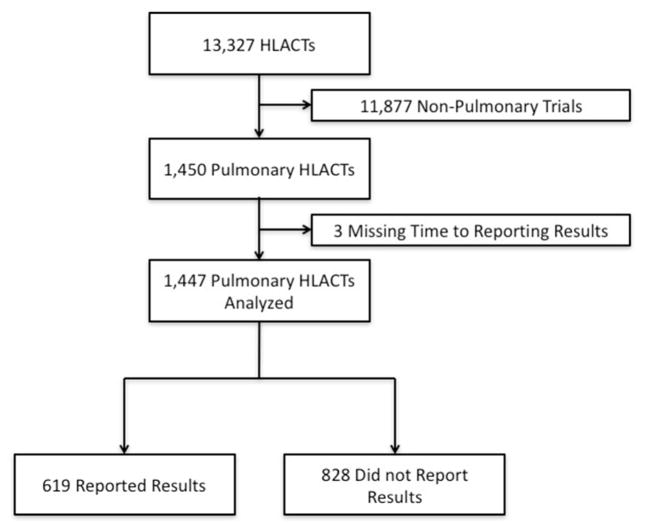

We identified 13,327 HLACTs in ClinicalTrials.gov. We excluded a majority (n=11,877) because they were non-pulmonary HLACTs (Figure 1). Of 1450 pulmonary HLACTs, 74.9% were drug HLACTs, 14.9% were studies of biologics, and 8.6% were device HLACTs. Most of the studies were funded by industry and 60.1% were conducted only in the US. The majority of pulmonary HLACTs were classified as “other respiratory conditions”, 26% focused on respiratory neoplasms, 16% on asthma, and 12% on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The median enrollment for pulmonary HLACTs was 98 subjects (IQR [34–339]) and median study duration was 21 months (IQR [9–38]). Most pulmonary HLACTs were randomized double-blinded (76.7%) and included at least 2 arms (75%). Pulmonary HLACTs phases were diverse with 7% phase 1/2, 40% phase 2, 2% phase 2/3, 26% phase 3, 13% phase 4 and 11% NA (Table 1). See online supplemental Table E5 for additional pulmonary HLACT characteristics.

Figure 1.

Clinical Trials Included in Analysis

HLACTs: Highly likely applicable clinical trials

Table 1.

Pulmonary Highly Likely Applicable Clinical Trials by Disease Category

| All trials N=1450 |

Neoplasm N=380 |

Asthma N=238 |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease N=175 |

Other N=657 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention groupa, n/N (%) | |||||

| Device | 125/1450 (8.6) | 9/380 (2.4) | 13/238 (5.5) | 12/175 (6.9) | 91/657 (13.9) |

| Biological | 216/1450 (14.9) | 44/380 (11.6) | 19/238 (8.0) | 4/175 (2.3) | 149/657 (22.7) |

| Drug | 1086/1450 (74.9) | 310/380 (81.6) | 206/238 (86.6) | 158/175 (90.3) | 412/657 (62.7) |

| Other | 23/1450 (1.6) | 17/380 (4.5) | 0/238 (0.0) | 1/175 (0.6) | 5/657 (0.8) |

| Phase, n/N (%) | |||||

| Phase 1/Phase 2 | 103/1450 (7.1) | 61/380 (16.1) | 8/238 (3.4) | 4/175 (2.3) | 30/657 (4.6) |

| Phase 2 | 579/1450 (39.9) | 252/380 (66.3) | 97/238 (40.8) | 58/175 (33.1) | 172/657 (26.2) |

| Phase 2/Phase 3 | 29/1450 (2.0) | 6/380 (1.6) | 3/238 (1.3) | 1/175 (0.6) | 19/657 (2.9) |

| Phase 3 | 383/1450 (26.4) | 40/380 (10.5) | 65/238 (27.3) | 76/175 (43.4) | 202/657 (30.7) |

| Phase 4 | 192/1450 (13.2) | 3/380 (0.8) | 44/238 (18.5) | 26/175 (14.9) | 119/657 (18.1) |

| N/A | 164/1450 (11.3) | 18/380 (4.7) | 21/238 (8.8) | 10/175 (5.7) | 115/657 (17.5) |

| Oversight authorities, n/N (%) | |||||

| United States: Food and Drug Administration | 1041/1450 (71.8) | 262/380 (68.9) | 181/238 (76.1) | 153/175 (87.4) | 445/657 (67.7) |

| United States: Non-Food and Drug Administration Only | 354/1450 (24.4) | 112/380 (29.5) | 46/238 (19.3) | 18/175 (10.3) | 178/657 (27.1) |

| No United States Oversight Authority | 55/1450 (3.8) | 6/380 (1.6) | 11/238 (4.6) | 4/175 (2.3) | 34/657 (5.2) |

| Funding sourceb, n/N (%) | |||||

| Industry | 1029/1450 (71.0) | 220/380 (57.9) | 191/238 (80.3) | 161/175 (92.0) | 457/657 (69.6) |

| NIH | 217/1450 (15.0) | 123/380 (32.4) | 20/238 (8.4) | 4/175 (2.3) | 70/657 (10.7) |

| Other | 204/1450 (14.1) | 37/380 (9.7) | 27/238 (11.3) | 10/175 (5.7) | 130/657 (19.8) |

| Enrollment (from results data) | |||||

| N | 622 | 134 | 95 | 79 | 314 |

| Median (25th – 75th) | 140 (41– 502) | 50 (21– 118) | 226 (54– 502) | 349 (108– 1055) | 183 (52– 539) |

| Primary completion yearc, n/N (%) | |||||

| 2008 | 367/1450 (25.3) | 95/380 (25.0) | 66/238 (27.7) | 35/175 (20.0) | 171/657 (26.0) |

| 2009 | 310/1450 (21.4) | 78/380 (20.5) | 48/238 (20.2) | 34/175 (19.4) | 150/657 (22.8) |

| 2010 | 299/1450 (20.6) | 85/380 (22.4) | 45/238 (18.9) | 39/175 (22.3) | 130/657 (19.8) |

| 2011 | 316/1450 (21.8) | 76/380 (20.0) | 58/238 (24.4) | 34/175 (19.4) | 148/657 (22.5) |

| 2012 | 158/1450 (10.9) | 46/380 (12.1) | 21/238 (8.8) | 33/175 (18.9) | 58/657 (8.8) |

Mutually exclusive intervention groups defined as follows. If study has device intervention then classified under device. Otherwise if study has biological intervention then classified under biological. Otherwise if study has drug intervention then classified under Drug. Otherwise classified under other.

Funding source derived from lead sponsor and collaborator information.

Study completion year used when primary completion year is missing. If study completion year also missing, verification year is used.

N/A: not applicable

Occurrence and timing of pulmonary HLACTs reporting results

A total of 619 pulmonary HLACTs reported results over the five-year study period, reflecting a cumulative percentage of 55.1% by 5 years for all pulmonary HLACTs. By disease group, 45.3% respiratory neoplasm HLACTs, 50.6% asthma HLACTs, 62.6% of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease HLACTs, and 59.8% of other pulmonary HLACTs reported results within the five-year study period (Figure 2). Approximately 15% (n=52) of pulmonary HLACTs reported results within one-year of the primary completion date. According to disease group, 12.9% respiratory neoplasm, 14.8% asthma, 20% chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and 14.9% of other pulmonary HLACTs reported results within the one-year reporting period.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Percentage of Trials Reporting Results

Pair-wise comparison of result reporting based by disease group over the 5-year study period.

*Neoplasm vs Other p=0.0001; †Neoplasm vs Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) p=0.004; ‡ Asthma vs Other p=0.03; COPD vs Other p=0.85; Asthma vs COPD p=0.07; Neoplasm vs Asthma p=0.29.

# One-year measured at 13 months

The percentage of HLACTs with reported results increased dramatically at the one-year milestone, with gradual incremental change in the percent reporting results during the subsequent years. Among HLACTs reporting results at any time over the five-year study period, the median (interquartile range) reporting time was 29 (16–47) months. When we compared cumulative reporting by disease category, the overall log-rank test identified at least one statistically significant difference between groups (p<0.001). Pairwise comparisons demonstrated that neoplasm HLACTs were less likely to report results compared with “other respiratory” HLACTs (p<0.0001) or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease HLACTs (p=0.004); asthma HLACTs were also less likely to report results than other HLACTs (p=0.03), but were not significantly different from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease HLACTs (p=0.07).

After reviewing the pulmonary HLACTS, we found that 141 of 1447 (9.7%) submitted a certification or extension request within 12 months of termination or completion of the study and 314 (21.7%) submitted a certification or extension request within the 5-year study period. Of the pulmonary HLACTs not reporting results during the study period, 214 of 828 (25.9%) trials potentially had a legally acceptable delay because of they submitted a certification or exemption request at some time during the study period.

Pulmonary HLACTs characteristics independently associated with lower likelihood of reporting and time trends in timely reporting

In multivariable Cox models, pulmonary HLACTs characteristics associated with a lower likelihood of reporting results during the five-year period included earlier HLACT phase, no Food and Drug Administration oversight, and having a non-National Institutes of Health or non-industry funding source. As compared to phase 4 HLACTs, earlier phase HLACTs were less likely to report results: adjusted hazard ratio of 0.41 (95% CI, 0.31–0.54) in phases 1/2 and 2; 0.55 (95% CI, 0.42–0.72) in phase 2/3 and 3; and 0.43 (95% CI, 0.29–0.63) in phase N/A (not applicable). Pulmonary HLACTs without Food and Drug Administration oversight were less likely to report results (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.65, 95% CI: 0.51–0.83) compared to HLACTs with the Food and Drug Administration oversight. Industry-funded and National Institutes of Health funded HLACTs had comparable reporting, but HLACTs with other funding sources (primarily academic or non-National Institutes of Health government trials) were less likely to report results (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.49, 95% CI: 0.34–0.71) when compared with National Institutes of Health funded HLACTs. Differences in results reporting between disease groups were attenuated towards the null (p=0.11) after adjustment for other trial characteristics. Trials that completed follow-up later in our study period had a slightly higher rate of reporting results than trials that completed earlier (adjusted hazard ratio 1.12 for each one year increment in completion year, 95% CI: 1.04 – 1.20). There was no evidence of interaction between disease group and study completion year for timely reporting of pulmonary HLACTs (Table 2), suggesting that the overall improvement in results reporting during our study period was similar across disease groups.

Table 2.

Cox Regression Model for Result Reporting within the 5 Year Study Period

| Characteristic | Adjusted HRa | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Phase | ||

| Phase 4 (reference) | 1.00 | - |

| Phase 1/2 & 2 | 0.41 | (0.31 – 0.54) |

| Phase 2/3 & 3 | 0.55 | (0.42 – 0.72) |

| N/A | 0.43 | (0.29 – 0.63) |

| Oversight | ||

| US the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act Oversight (reference) | 1.00 | - |

| No US the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act oversight | 0.65 | (0.51 – 0.83) |

| Funding source | ||

| NIH (reference) | 1.00 | - |

| Industry | 0.78 | (0.60 – 1.01) |

| Other | 0.49 | (0.34 – 0.71) |

| Total enrollment | ||

| Per 100 participants, for enrollment <600 | 1.10 | (1.05 – 1.17) |

| Per 100 participants, for enrollment >600 | 0.98 | (0.89 – 1.07) |

| Primary completion year | ||

| Primary completion year, per year | 1.12 | (1.04 – 1.20) |

| Disease group | ||

| Other (reference) | 1.00 | - |

| Neoplasm | 0.78 | (0.59 – 1.03) |

| Asthma | 0.77 | (0.60 – 0.98) |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 0.94 | (0.71 – 1.24) |

Adjusted for: primary purpose of trial, intervention group, phase, the Food and Drug Administration oversight, funding source, enrollment size, trial status, primary year of completion, study duration, number of arms, use of randomization, masking, disease studied.

Variables not listed in the table were not statistically significant

N/A: not applicable

Conclusions

In this study of five years of data collected through ClinicalTrials.gov, over half of all pulmonary HLACTs reported results to the Clinicaltrials.gov database since the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act regulations were enacted in 2007. However, only 15% of pulmonary HLACTs reported results within one year of completion or termination, the time mandated by federal regulation. Reporting was particularly low in HLACTs evaluating interventions for asthma, early phase HLACTs, HLACTs without the Food and Drug Administration oversight and those funded by academic institutions or other non-National Institutes of Health federal agencies. Reporting improved in all disease conditions (e.g., asthma, neoplasm, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, other) over the 5-year study period. Our findings demonstrate a need for improved reporting among pulmonary HLACTs overall and identification of specific types of studies for which efforts to improve reporting should be more focused.

Prior studies have examined reporting behaviors for all HLACTs but have not specifically focused on pulmonary HLACTs. Our findings for pulmonary HLACTs were comparable to all HLACTs for reports within one year of HLACTs completion (13.4 % overall versus 15% for pulmonary HLACTs), and pulmonary HLACTs fared better than the overall group for reports within our five-year study window (38.3% overall versus 55.1% for pulmonary HLACTs). However, pulmonary HLACTs had longer median time to reporting (17 months versus 29 months) when compared to reports on all HLACTs, respectively.16 Our finding that early phase HLACTs, HLACTs with no the Food and Drug Administration oversight, and those with other funding sources were less likely to report results during the 5-year study period were similar to findings among all HLACTs. However, Anderson et al. also found that other intervention types (non-drug, non-device, and non-biologic) were less likely to report results during the five-year study period in all HLACTs.16, 24

As of September 21, 2016, the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services have finalized policies to expand mandatory reporting of basic summary results to the ClinicalTrials.gov database.2, 25 In the Final Rule for Clinical Trial Registration and Results, Health and Human Services requires submission of results of all Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act regulated medical products, regardless of approval status, to be reported within one year of trial completion. Additionally, the final rule now requires the submission of full protocol and statistical analysis plan at the time of results submission, more detailed information about adverse events (e.g., collection method and event time-frame), and requires the reporting of race and ethnicity as a part of demographic data.2, 8, 25, 26 The National Institutes of Health has expanded mandatory registration and reporting of basic summary results of all National Institutes of Health funded trials, including those not subject to the Final Rule.8, 25, 27 Failure to comply with the Final Rule may result in civil monetary penalty actions imposed by the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act, public disclosure of non-compliance status, and possible loss of funding for those applicable clinical trials funded by Health and Human Services. Under National Institutes of Health’s policy, an institution may lose funding if it cannot verify registration and results reporting from all National Institutes of Health funded trials.2, 8, 25, 28, 29

Policies requiring results reporting have the potential to transform clinical research by enhancing transparency on the process of research and by minimizing the impact of reporting and publication bias.30 It is well known that studies with negative findings are often not reported as conducted and often do not have their findings published.18, 31 Improved transparency regarding the conduct and outcomes of these studies could decrease the likelihood of redundant and/or unnecessary consideration of ineffective therapies, and speed the pace of research and the discovery of effective clinical treatments. It could also enhance clinicians’ and policy makers’ capacity to make informed decisions based on all available evidence.6, 8, 11, 32 Nonetheless, experience with these policies is relatively new, and potential disadvantages to their implementation may not yet have fully evolved.6, 11, 16, 17, 24, 33–36

Strategies to improve reporting should be centered around institutional priorities to promote awareness and compliance among clinical investigators and sponsors of research.1, 2, 25, 37 Institutions can require ClinicalTrials.gov registration as a condition of institutional review board approval and results reporting for institutional review board renewal. To minimize the burden of data entry, institutions can create an interface to transfer data that is commonly collected during yearly process reports or institutional review board renewals. Other strategies include the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors requiring and not “recommending” posting of clinical trial results in a public registry. In 2004, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors made registration in a publically accessible registry a prerequisite for publication resulting in a substantial increase in the number of trials in the ClincalTrials.gov database.4, 37

Our study has limitations. First, we identified HLACTs based on a National Library of Medicine-based algorithm which has been previously shown to have an estimated false negative rate of 16–19% and false positive rate of 4.4%.16 Second, some pulmonary HLACTs may have been excluded because they did not have medical subject heading terms under the Respiratory Tract Diseases subheading. Thus, it is possible we did not identify some truly eligible pulmonary HLACTs through our approach. Third, some HLACTs may not have been legally required to report summary results within one year because of certifications or extensions allowed through the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act, which may have limited our accuracy in estimating compliance with the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act. A previous study found that 6.1% of all HLACT not reporting results at one-year had submitted applications for certifications and/or exemption while 12.1% not reporting at five-years had submitted such applications.16 Fourth, the reported hazard ratios may overestimate relative differences during the early study period and potentially underestimate differences during the latter study period due to the dramatic increase in reporting at the one-year milestone and greater differentiation between reporting patterns of different types of studies after the one-year mark.

In conclusion, we found suboptimal reporting of pulmonary clinical HLACTs findings in ClinicalTrials.gov despite a federal mandate. Pulmonary investigators should be aware of the federal mandate, with special attention paid to reporting results of earlier phase HLACTs, HLACTs not requiring Food and Drug Administration oversight, and HLACTs with non-industry or non-National Institutes of Health funding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund Research Supplements to Promote Diversity in Health Related Research under Award Number 3U54AT007748-02S1

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest

None

References

- 1.Dechartres A, Riveros C, Harroch M, et al. Characteristics and public availability of results of clinical trials on rare diseases registered at clinicaltrials.gov. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:556–558. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. Trial reporting in ClinicalTrials.gov - The final rule. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1998–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1611785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [accessed 12 October 2017];Public Law 105–115: Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997. 1997 Adopted November 21, 1997, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-105publ115/pdf/PLAW-105publ115.pdf.

- 4.Pansieri C, Pandolfini C, Bonati M. The evolution in registration of clinical trials: a chronicle of the historical calls and current initiatives promoting transparency. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:1159–1164. doi: 10.1007/s00228-015-1897-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine C, Horton R, DeAngelis CD, et al. Clinical trial registration—looking back and moving ahead. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2734–2736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe078110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tse T, Williams RJ, Zarin DA. Reporting “basic results” in ClinicalTrials.gov. Chest. 2009;136:295–303. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. [accessed 12 October 2017];Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007. 2007 https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ85/html/PLAW-110publ85.htm.

- 8.Zarin DA, Tse T, Sheehan J. The proposed rule for US clinical trial registration and results submission. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:174–180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1414226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalowitz DI, Miller FG. Disclosing individual results of clinical research: implications of respect for participants. JAMA. 2005;294:737–740. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesselheim AS, Mello MM. Confidentiality laws and secrecy in medical research: improving public access to data on drug safety. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:483–491. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarin DA, Tse T. Moving towards transparency of clinical trials. Science. 2008;319:1340–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.1153632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karassa FB, Ioannidis JP. Clinical trials: A transparent future for clinical trial reporting. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11:324–326. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer DB, Cutlip DE. Regulatory science: Trust and transparency in clinical trials of medical devices. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:503–504. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mintzes B, Lexchin J. Clinical trial transparency: many gains but access to evidence for new medicines remains imperfect. Br Med Bull. 2015;116:43–53. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldv042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:373–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson ML, Chiswell K, Peterson ED, et al. Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1031–1039. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1409364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen TA, Dechartres A, Belgherbi S, et al. Public availability of results of trials assessing cancer drugs in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2998–3003. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.9577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones CW, Handler L, Crowell KE, et al. Non-publication of large randomized clinical trials: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6104. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd JL, White KR, Chiswell K, et al. Using ClinicalTrials.gov to understand the state of clinical research in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10:411–417. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201305-111OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ClinicalTrials.gov. [Accessed 12 October 2017];FDAAA 801 Requirements. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/manage-recs/fdaaa.

- 21.US National Library of Medicine. [Accessed 12 October 2017];Medical Subject Headings. 2015 https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/techbull/so14/so14_2015_mesh_avail.html.

- 22.Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, et al. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:1838–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tasneem A, Aberle L, Ananth H, et al. The database for aggregate analysis of ClinicalTrials.gov (AACT) and subsequent regrouping by clinical specialty. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law MR, Kawasumi Y, Morgan SG. Despite law, fewer than one in eight completed studies of drugs and biologics are reported on time on ClinicalTrials.gov. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2338–2345. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudson KL, Lauer MS, Collins FS. Toward a new era of trust and transparency in clinical trials. JAMA. 2016;316:1353–1354. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health and Human Services. Clinical trials registration and results submission. Fed Regist. 2014;79:69566–69680. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Institutes of Health. Announcement of a draft NIH policy on dissemination of NIH-funded clinical trial information. Fed Regist. 2015;80:8096– 8098. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loder E, Groves T. The BMJ requires data sharing on request for all trials. BMJ. 2015;350:h2373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morley G. Regulatory writing: New developments in public disclosure of clinical trials. Medical Writing. 2015;24:153–154. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, et al. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252–260. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripathy D. Negative is positive: A plea to publish all studies regardless of outcome. Am J Hematol Oncol. 2015;11:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. [accessed 12 October 2017];WHO statement on public disclosure of clinical trial results. 2015 http://www.who.int/ictrp/results/reporting/en/

- 33.Tse T, Zarin DA. Clinical trial registration and results reporting. [accessed 12 October 2017];Update. 2009 https://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/publications/FDLI-Update_2009_508.pdf.

- 34.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, Califf RM, et al. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database—update and key issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:852–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1012065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill CJ. How often do US-based human subjects research studies register on time, and how often do they post their results? A statistical analysis of the Clinicaltrials.gov database. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001186. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prayle AP, Hurley MN, Smyth AR. Compliance with mandatory reporting of clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2012;344:d7373. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taichman DB, Backus J, Baethge C, et al. Sharing clinical trial data--A proposal from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:384–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1515172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.