Abstract

We present a case of a patient with diabetes with a pleural empyema originated from a pyomyositis process established after a central line procedure. This empyema later on extended into the spinal canal deriving into an epidural empyema, leading towards a spinal neurogenic shock and death. We discuss the anatomical substrate for this extension as well as the anatomopathological findings observed in the autopsy.

Keywords: Infection (neurology), Spinal Cord, Pathology, Neurological Injury, Neurosurgery

Background

Patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, are at an increased risk for disseminated as well as localised severe infections in the form of abscesses and empyema. We present a patient with a chief complaint of progressive tetraparesis. He was found to have pleural empyema associated with pectoral pyomyositis, which later extended into the spinal canal deriving into an epidural empyema. Here, we explore the anatomical substrate for such extension of the infection. This case also exemplifies the need for a high clinical suspicion for an intraspinal pathology diagnosis, whenever assessing a patient presenting with progressive weakness, and also the urgency for prompt imaging, antibiotic therapy initiation and surgical treatment.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old man with a medical history relevant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) presented to the emergency room with 2 days of progressive ascending tetraparesis. There was no compromise of urinary or faecal sphincters. During the 21 days prior to presentation, he had respiratory symptoms consistent for a cough and mild dyspnoea, which were treated as an influenza syndrome. On presentation, vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination included a normal mental exam, as well as unremarkable heart, lungs and abdominal evaluations. Neurological assessment was relevant for tetraparesis, which was more evident on lower extremities, as well as decreased deep tendon reflexes, despite preservation of sensibility including pain, temperature and vibration. There was no sensory level identified. A palpable, though poorly defined, mass was described in the left supraclavicular region.

Of note, the patient had been admitted to the Haematology Department, 2 months prior to presentation. During this hospitalisation, the patient had a left subclavian vein central line placed in order to receive gamma globulin, vincristine and steroids for his ITP. He was then discharged on prednisone daily.

Initial chest radiographs showed a radiopaque image on the superior left lung field that coincided with the palpable mass previously described. Nerve conduction studies showed an axonal, secondarily demyelinating, asymmetric motor and sensitive polyneuropathy.

One day after admission, the patient’s dyspnoea worsened and he became hypoxaemic. On examination, use of accessory respiratory muscles, cryodiaphoresis and acute metabolic encephalopathy were noted. The patient had acute hypoxic respiratory failure requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. Prior to intubation, the patient presented complete lower extremity paresis. He was then started empirically on anticoagulation and given concern for pulmonary embolism, a chest CT angiography (CTA) was obtained, as well as blood and urine cultures. Control chest radiographs showed a mediastinal mass that displaced the trachea, atelectasis in the upper lobe of the left lung, moderate cardiomegaly and a left pleural effusion.

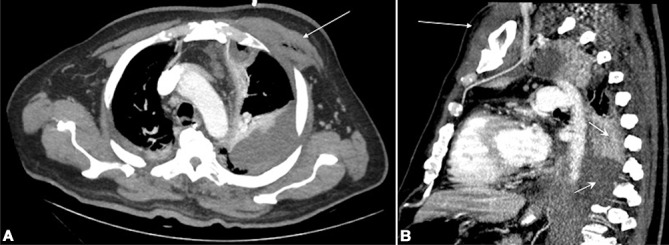

Chest CTA was negative for filling defects in the large pulmonary arteries and mediastinal tumours; however, there were large bilateral pleural effusions, left greater than right, with secondary atelectasis. Also, there were parcelled basal consolidation foci predominating on the left lung. Pyomyositis and gas in the pectoralis major muscle and soft tissues around it were observed (figure 1A). This exudate extended toward the anterior and posterior mediastinum contacting both the anterior thoracic wall, as well as the vertebrae and the spinal canal (figure 1B). Pleurocentesis with insertion of a chest tube was performed and samples obtained were consistent with an empyema. The patient was started on antibiotics with cefotaxime and metronidazole. Chest radiograph obtained after pleurocentesis showed the absence of trachea deviation and partial resolution of the pleural effusion with re-expansion of the left lung.

Figure 1.

Thoracic CT scan (A) axial and (B) sagittal cuts showing pectoralis major pyomyositis (long arrows) and pleural empyema (short arrows) contacting the thoracic vertebrae.

The following day, the patient presented with increasing dysautonomia secondary to either spinal neurogenic and/or septic shock. He died the same day. Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus grew in both blood and empyema cultures.

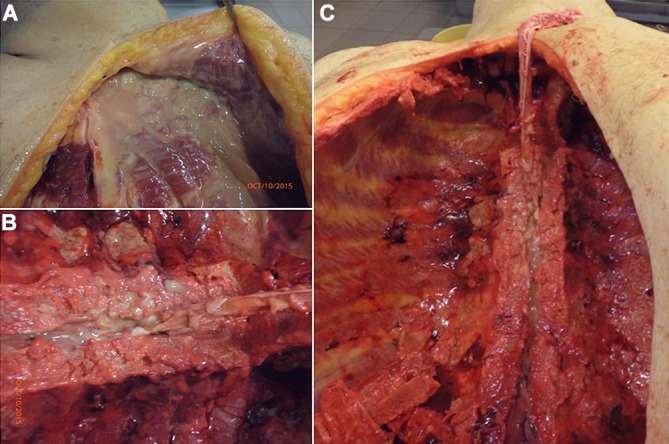

Autopsy performed on this patient showed a purulent exudate filling most of the thoracic cavity, extending posteriorly (figure 2A). This purulent exudate surrounded the cervical and thoracic vertebrae and filled the spinal canal (figure 2B,C). Both pleurae were markedly thickened and had abundant empyema surrounding them. Each of the lungs weighted 250 g; they appeared congestive but without consolidating foci. Pulmonary arteries did not show any thrombi. The heart had hypertrophy of the left ventricle with no evidence of myocardial infarction. Heart valves had no abnormalities, and the aorta showed calcified atherosclerotic plaques in approximately 70% of its extension without ulcerations. Abdominal organs had mild congestion with diffuse dilatations of the viscera. The brain and cerebellum did not show any abnormalities. The spine was oedematous with abundant purulent exudate.

Figure 2.

The opening of thoracic cavity during autopsy disclosed a purulent collection in (A) the upper sternum and left upper ribs, extending into (B and C) the medullary canal.

Microscopic evaluations showed polymorphonuclear infiltrates in both pleurae with congestion, without evidence of infection of both lungs. Pectoralis major muscle samples obtained also evidenced striking myositis with polymorphonuclear inflammation and oedema. There was a marked polymorphonuclear infiltrate around the dura mater establishing an epidural empyema diagnosis; however and interestingly, the spine was not compromised and only showed mild oedema without inflammatory infiltrate.

Even though the acute onset of weakness in this patient prompted for a spinal MRI, we initially deferred this diagnostic study considering the absence of myelopathic features (ie, sensory level, sphincter dysfunction and pyramidal signs). Later on, when the patient worsened his paresis, we were still not able to perform an MRI since he became markedly haemodynamically unstable, thus precluding the possibility of transferring him to our MRI facilities. In retrospect, the contiguity of the thoracic empyema with the spinal canal, as seen in the chest CT scan, should have hinted us about the possibility of a spinal neurogenic shock due to an epidural empyema.

Discussion

A pleural empyema is defined as pus in the pleural space, most often secondary to pneumonia, though other aetiologies include trauma and iatrogenic.1 A spinal epidural abscess is defined as a collection of pus in the epidural space, which is a surgical emergency, as prolonged compression of the spine may lead to irreversible damage.2 There have been few reports of empyema extending to the epidural space leading to an epidural abscess,3–6 as well as one case of tuberculosis which spread to the subdural space and intrathecally to the spine.7 In our case, we confirmed the extension of a pleural empyema to free pus in the medullary canal of the spine, without trespassing the dura mater. It could have been that the pleural empyema, extended first to form a spinal epidural abscess, which then ruptured leading to pus in the spinal canal. Or else, a direct extension of this patient’s overwhelming empyema into the spinal canal, deriving into an epidural empyema without a surrounding capsule. Certainly, the pleural empyema was related to the pectoral pyomyositis, which could have been iatrogenic after the left subclavian vein central line placement procedure.

Anatomy of the thoracic empyema: epidural abscess/empyema pathway

Central nervous system (CNS) infections can result from infection at sites distant or contiguous to the CNS.2 Spinal epidural abscess is an infrequent entity constituted by the presence of purulent material in the spinal epidural space. Adult, immunocompromised patients with an active septic focus are at increased risk.8

Micro-organisms can reach the spinal epidural space by three pathways: a first pathway involving haematogenic dissemination from distant focuses, with the skin being the most frequent. Infection due to haematogenous spread may originate from all types of extra spinal sites that lead to a persistent or temporary bacteremia.9 Vascular theories for bacterial dissemination include both arteries and veins. Spinal arteries (which ascend and descend to supply vertebral bodies) enter the spinal canal through the intervertebral foramen. Bacteria could easily spread and result in osteomyelitis, discitis and spinal abscesses. Veins could also play a role due to the valve-less vertebral venous plexus that connects pelvic and vertebral drainage. In situations of increased intra-abdominal pressure, haematogenous and bacterial translocation may be promoted and stablish infectious foci in the spinal column.10

A second pathway, by continuity, extending directly from abscesses in the paraspinal, psoas or retropharyngeal as well as the pleural spaces. Contiguous spread accounts for one-third and haematogenous dissemination for about half of the cases.8 As above, continuity cases have been reported of epidural abscesses after pleural empyema involving mycobacteria, aspergillus species and, like our patient, S. aureus as a causative agent.3–6

The third pathway for an epidural infection can be due to a disruption of the epidural space such as in trauma, surgery and lumbar punctures.10

Pathophysiology, involving the anatomical continuity of pleural and epidural spaces, has been described in the context of pneumorachis (presence of air in the spinal canal) secondary to aetiologies such as asthma, recurrent vomiting or trauma, with air migration to the mediastinum. In these situations, air can separate the mediastinal pleura from the aorta and the parietal pleura from the spine, therefore entering the epidural space via the intervertebral foramina.11 Other cases have been described of pleural involvement by lateral extension of abscesses involving the parietal pleura, in Pott’s disease.12 It becomes clear how the intervertebral foramina constitute the principal routes of entry and exit to and from the vertebral canal. They allow for the passage of the spinal nerve roots, their coverings and vasculature at the same time permitting the communication between the lumen of the vertebral canal (epidural space, meninges and spinal cord) and the paravertebral soft tissues, which may be important in the spread of pathological processes such as tumours or infections.13 Given this anatomical continuum and the findings described in this patient’s imaging and autopsy report, suggest that the spinal infection derived from direct extension of the pleural space, posteriorly to the vertebrae, in through the intervertebral foramina and into the spinal canal.

Learning points.

Spinal epidural abscess/empyema is an infrequent entity constituted by the presence of purulent material in the spinal epidural space.

Micro-organisms can reach the spinal epidural space by three pathways: haematogenous spread, by continuity and due to a disruption of the epidural space.

Spinal infection can be derived from direct extension of the pleural space, posteriorly to the vertebrae, in through the intervertebral foramina and into the spinal canal.

With the autopsy results illustrating the anatomy of the pectoral to thoracic to spinal spread of the infection, any new lower limb neurological symptom, presenting with a thoracic empyema, should be investigated for spinal/epidural involvement.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed to and agreed on the content of the manuscript. The respective roles of each author are as follows: GTA conceptualised the report and made substantial contributions to the design, drafting and revision of the work. SJH, GCU and GRR significantly contributed to drafting and critically reviewing the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and assume accountability for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Redden MD, Chin TY, van Driel ML. Surgical versus non-surgical management for pleural empyema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3:CD010651 10.1002/14651858.CD010651.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald LK, Quisling RG. Central nervous system Infections Textbook of neurointensive care, 2013:p. 427–517. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gómez-Caro Andrés A, Díaz-Hellín Gude V, Moradiellos Díez FJ, et al. Spinal cord compression and epidural abscess extension of pleural empyema. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2004;3:317–8. 10.1016/j.icvts.2004.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendrix WC, Arruda LK, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Aspergillus epidural abscess and cord compression in a patient with aspergilloma and empyema. Survival and response to high dose systemic amphotericin therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:1483–6. 10.1164/ajrccm/145.6.1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lescan M, Lepski G, Steger V, et al. Rapidly progressive paraplegia and pleural empyema: how does that correlate? Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;61:640–2. 10.1007/s11748-012-0199-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong M, Lanka L, Hussain Z, et al. Epidural extension of infected chest wall haematoma and empyema causing spinal cord compression. Heart Lung Circ 2014;23:e20–e23. 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alessi G, Lemmerling M, Nathoo N. Combined spinal subdural tuberculous empyema and intramedullary tuberculoma in an HIV-positive patient. Eur Radiol 2003;13:1899–901. 10.1007/s00330-002-1678-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darouiche RO. Spinal epidural abscess. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2012–20. 10.1056/NEJMra055111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reihsaus E, Waldbaur H, Seeling W. Spinal epidural abscess: a meta-analysis of 915 patients. Neurosurg Rev 2000;23:175–204. 10.1007/PL00011954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avilucea FR, Patel AA. Epidural infection: Is it really an abscess? Surg Neurol Int 2012;3(Suppl 5):S370–6. 10.4103/2152-7806.103871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ould-Slimane M, Ettori MA, Lazennec JY, et al. Pneumorachis: a possible source of traumatic cord compression. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96:825–8. 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malhotra HS, Garg RK, Lalla R, et al. Paradoxical extensive thoracolumbosacral arachnoiditis in a treated patient of tuberculous meningitis. Case Rep Child Meml Hosp Chic 2012;2012:bcr2012006262 10.1136/bcr-2012-006262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Standring S. Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 41 edn New York: Elsevier Limited, 2016:1562. [Google Scholar]