Abstract

A 56-year-old healthy woman presents with 2-year history of symptoms classic for pheochromocytoma. Evaluation revealed one of the largest cystic pheochromocytomas reported but without any metastatic disease. After achieving medical management of her symptoms, surgical removal was performed successfully and without any complications intraoperatively. Pathology of the mass confirmed the diagnosis. The patient had complete resolution of her symptoms thereafter.

Keywords: Urology, Pathology, Endocrinology, Adrenal Disorders

Background

Pheochromocytomas are rare catecholamine-producing tumours from chromaffin cell lines. Most cases are benign; however, up to 10% are malignant with metastases present. Currently, there are no fatures that can distinguish one from the other. Classic symptoms include palpitations, headaches, hypertension and sweating. Diagnosis is initially confirmed with elevated urinary catecholamines or plasma metanephrines, as well as functional imaging such as CT, MRI or nuclear medicine. This case report describes a patient with one of the largest discovered benign pheochromocytomas with classic symptoms.

Case presentation

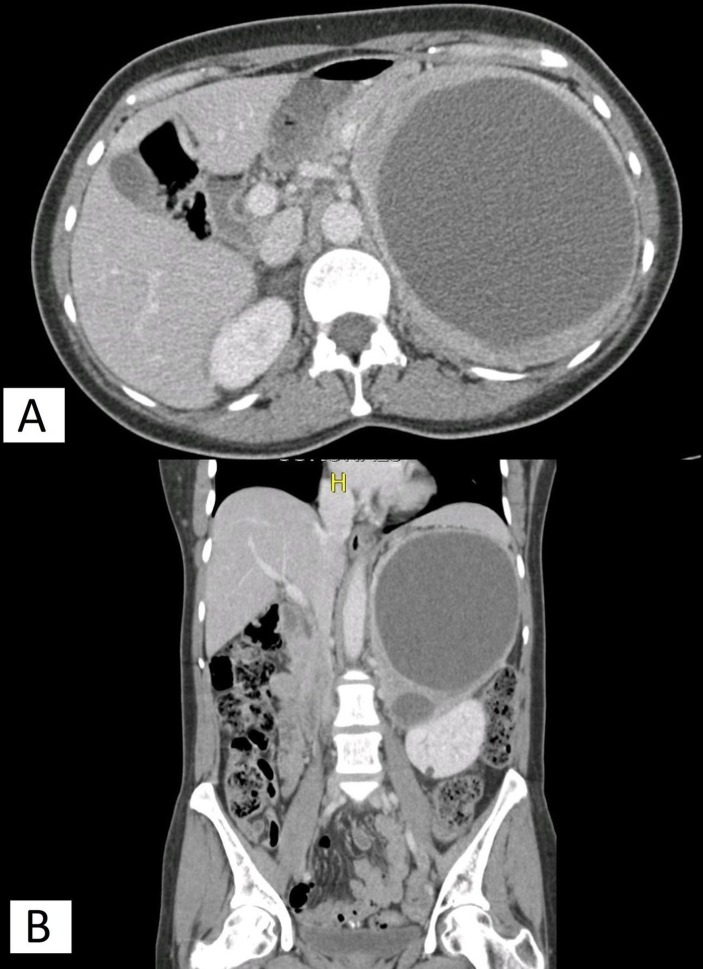

The 56-year-old woman was worked up at a family practice clinic in June 2016 for sudden onset nausea, vomiting and fainting spells. She had recently moved from Puerto Rico and was found to have an elevated blood pressure of 160/120 mm Hg, accompanied by a palpitation. A retroperitoneal ultrasound revealed a large left retroperitoneal mass. On further questioning, the patient reported a 2-year history of excessive sweating during the day and night, head cold intolerance, increased hair loss, lower back pain, palpitations and an inability to lay on her left side due to a pounding sensation in her head. She also endorsed prolonged treatment by her primary care provider in Puerto Rico for hypertension with three antihypertensive medications: losartan (50 mg daily), amlodipine (10 mg daily) and metoprolol (7.5 mg daily). A CT scan of the abdomen was then ordered, which demonstrated a 16.7 cmx15 cmx11.9 cm mixed solid and cystic mass in the left upper quadrant, felt to be an adrenal mass, with significant mass effect (figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Axial view of left adrenal mass on CT. (B) Coronal view of left adrenal mass with mass effect on left kidney.

She was evaluated in urology clinic. At our clinic, she had a normal blood pressure and heart rate. The physical examination revealed a palpable non-tender mass in the left upper quadrant. Laboratories were obtained and revealed a normal urinalysis, normal chemistry except for slightly elevated glucose at 103 mg/dL. Meanwhile, 24 hours urine metanephrines were elevated at 30 115 μg, normetanephrines were elevated at 16 913 μg, for a total metanephrine level of 47 028 μg. Twenty-four hour urine studies were also elevated with epinephrine at 395 μg, norepinephrine at 387 μg and dopamine at 693 μg. A CT scan of the chest was obtained and did not demonstrate any metastatic disease. Cardiology was consulted and obtained a transthoracic echocardiogram, which was negative for any pathology with an ejection fraction of >65%. Endocrinology service recommended discontinuation of metoprolol and initiation of doxazosin (1 mg daily) as well as a high salt diet for volume expansion. A 131-I-methyliodobenzylguanine (MIBG) scan was obtained and confirmed the increased uptake in the periphery of the cystic lesions in the left upper quadrant but showed no areas concerning for metastatic disease. Plasma metanephrines and normetanephrines drawn 1 day prior to surgery were both elevated at 50 nmol/L. She was haemodynamically stable with normal heart rate and blood pressure on admission. However, she did admit to worsening left flank plain.

Treatment

The patient underwent left en bloc adrenalectomy 6 weeks after initial consultation. This was performed through a Chevron incision. The colon was noted to be tightly adhered but was then mobilised medially along with its mesentery. The pancreas was mobilised after ligation of the tumour vessels with LigaSure. The mass was noted to be adhered to the aorta and superior mesenteric artery but was successfully dissected off these structures. The tumour was separated from the left kidney. Several adrenal veins were seen providing collateral circulation between the kidney and adrenal gland. These were all individually ligated and divided. No obvious metastases were observed. The duration of the procedure was 281 min with an estimated blood loss of 200 mL. No intraoperative complications were encountered.

Outcome and follow-up

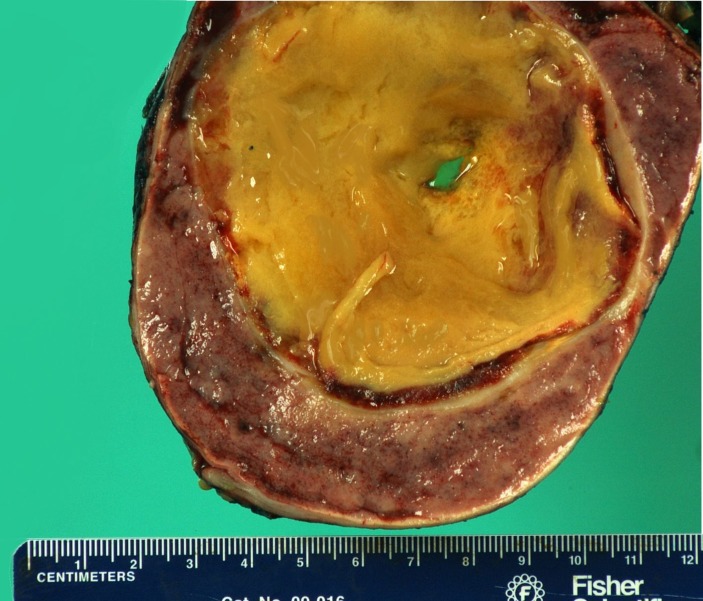

Gross examination of the specimen showed an ovoid, tan-pink soft tissue fragment that weighed 1773 g and measured 21.0×13.0×12.5 cm with up to 0.5 cm of periadrenal adipose tissue (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pheochromocytoma.

Sectioning through the specimen showed a tan-brown, firm, well-circumscribed, encapsulated mass measuring 21.0×12.0×10.5 cm with multiple smooth cystic areas measuring up to 17 cm in greatest diameter that were filled with a friable tan-yellow substance (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cross-section of the friable tan mass within the tumour.

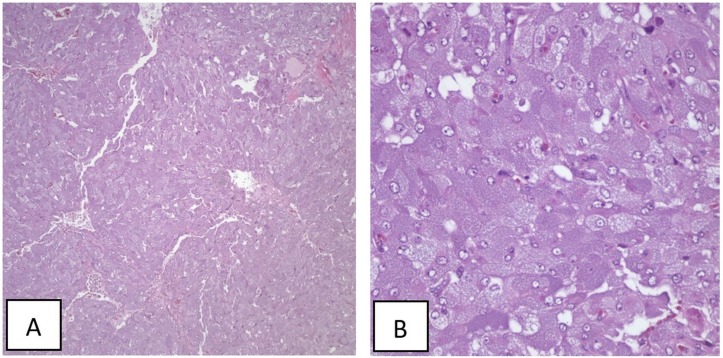

H&E stained sections showed a well-circumscribed tumour surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Tumour cells were round, arranged in nests with a rich vascular network forming a zellballen, with a granular amphophilic cytoplasm containing an oval nucleus with salt and pepper chromatin (figure 4).

Figure 4.

H&E stains in (A) 10× view and (B) 40× view.

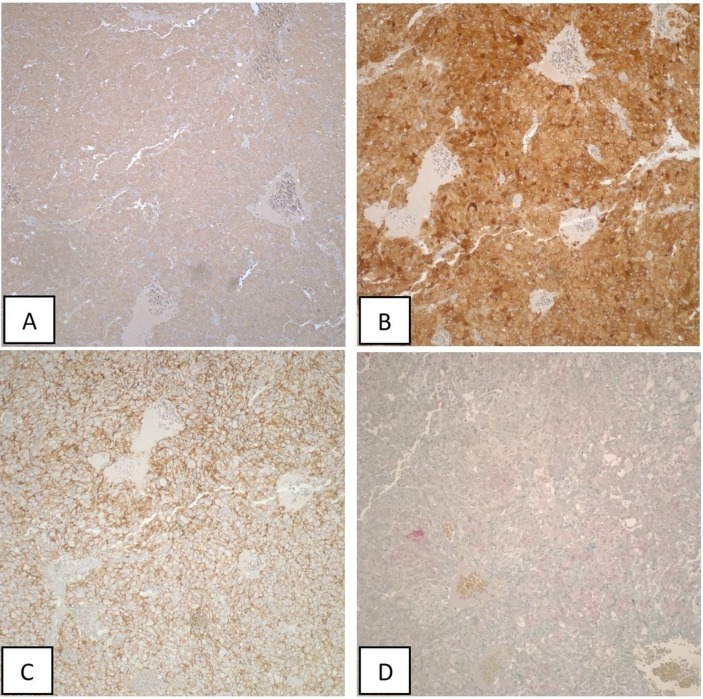

Marked pleomorphism was also seen within a few tumour cells. The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was made. Immunohistochemistry was performed with tumour cells showing strong positivity to chromogranin (figure 5A), synaptophysin (figure 5B), CD56 (figure 5C) and focally to S100 (figure 5D) confirming the diagnosis.

Figure 5.

Histochemistry of the tumour.

The patient was admitted to the ICU postoperatively for close observation and was downgraded to the regular floor after 1 day. She was discharged on the sixth postoperative day. At that time, plasma metanephrines and normetanephrines were within normal limits. She was then seen in our clinic at 1 month and 4 months postoperatively. She endorsed complete resolution of her previous symptoms and had ceased taking all of her antihypertensive medications. The CT scan at 4 months was negative for any recurrence or metastases. Her plasma metanephrines were within normal limits.

Discussion

Pheochromocytomas are rare neuroendocrine tumours of chromaffin cell origin found mainly in the adrenal gland.1 Up to 25% of cases can be extra-adrenal and are known as paraganglionomas. The classic triad for presentation is headaches, palpitations and hypertension. Diagnosis begins typically with metabolic testing involving either with plasma metanephrines or 24 hours urinary catecholamines. Imaging is performed to localise tumours and to detect metastases. Preoperative alpha-blockade is used to counter the effects of the circulating catecholamines.2 Cardiovascular complications are a lethal sequela of this pathology.3 Cardiac work-up should be considered.

Tumours over 20 cm have rarely been described in the literature.4 The largest recorded adrenal pheochromocytoma was reported by Basso, in which they removed a 29x21x12 cm tumour attached to a normal left adrenal gland.5 In this case, the patient was asymptomatic at presentation and without any detected elevation in catecholamine production. The patient was free of recurrence up to 8 months, when liver metastases were discovered. Another paper describes a pheochromocytoma that weighed 3150 g.6 The patient they reported presented with minimal symptoms of pain and only mildly elevated urinary catecholamine metabolites. Our patient had a mass with a maximum diameter of 21 cm with hypertension requiring three antihypertensive medications as well other classic symptoms of excess catecholamine production. However, our patient did not have any metastases and thus far has not had any evidence of recurrence. This case describes one of the largest benign cystic pheochromocytomas.

Malignancy in adrenal pheochromocytomas is present in up to 10% of cases.7 Currently, there are no clear predictive markers or features and only the presence of clinical metastases define a malignancy. Previous initial reports attempted to predict malignancy by size, setting 6 cm or larger as increased risk for malignancy.8 Thompson compared the histological features of 50 benign pheochromocytomas with 50 malignant ones.9 They described histological findings, such as invasion, necrosis, atypical or increased mitotic figures, large nests of diffuse growth, nuclear pleomorphism and others that were more commonly found in malignant tumours. They weighted each characteristic to create the pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) and noted that more biologically aggressive tumours all had a PASS of ≥4 (out of 20). However, one retrospective analysis of 98 cases argues that neither tumour size nor the PASS can reliably predict the risk of malignancy.10

Another rare feature of the case presented here is its cystic components. Pheochromocytomas are typically a solid organ and only few have been described as cystic in the literature. Certainly, this case is one of the largest ones discovered. The component of the cystic fluid in one reported case was found to have high concentrations of catecholamines and metanephrines.11 Clinically, this is important as these may circulate intravenously as the mass is isolated during surgical removal. In fact, in the case report described above, despite adequate alpha-blockade starting 3 weeks prior to surgery, anaesthetic induction alone caused a hypertensive crisis that prevented the surgery.

Operative mortality can be <1% in the hands of experienced surgeons and anaesthesiologists.1 Long-term prognosis is excellent, but 10-year recurrence rates can be as high as 16%, so vigilant follow-up is required. Although, no consensus on follow-up exists, a typical regimen can include a thorough history and physical, blood pressure measurement and biochemical markers every 6–12 months earlier on and then annually up to 10 years.12 Imaging should be obtained as indicated.

Learning points.

Although the classic clinical presentation of pheochromocytomas may appear with small tumours, several instances have been reported of large tumours with no or minimal symptoms.

There are currently no reliable clinical, laboratory or pathological markers for diagnosing metastatic pheochromocytomas.

Careful surgical excision of cystic pheochromocytomas are indicated to prevent spillage of cystic fluid containing high levels of catecholamines and metanephrines.

Long-term prognosis is excellent even in large tumours after surgical removal.

Footnotes

Contributors: DK was the primary surgeon for the subject and oversaw the authorship of the case report by critically reviewing the paper at each step. GG reviewed the pathology slides and provided the descriptive details of the findings. KMC primarily wrote the manuscript and performed the literature review.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, et al. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet 2005;366:665–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacak K. Preoperative management of the pheochromocytoma patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:4069–79. 10.1210/jc.2007-1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira VM, Marcelino M, Piechnik SK, et al. Pheochromocytoma Is Characterized by Catecholamine-Mediated Myocarditis, Focal and Diffuse Myocardial Fibrosis, and Myocardial Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2364–74. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munakomi S, Rajbanshi S, Adhikary PS. Case Report: A giant but silent adrenal pheochromocytoma - a rare entity. F1000Res 2016;5:290 10.12688/f1000research.8168.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basso L, Lepre L, Melillo M, et al. Giant phaeochromocytoma: case report. Ir J Med Sci 1996;165:57–9. 10.1007/BF02942808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basiri A, Radfar MH. Giant cystic pheochromocytoma. Urol J 2010;7:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szalat A, Fraenkel M, Doviner V, et al. Malignant pheochromocytoma: predictive factors of malignancy and clinical course in 16 patients at a single tertiary medical center. Endocrine 2011;39:160–6. 10.1007/s12020-010-9422-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arcos CT, Luque VR, Luque JA, et al. Malignant giant pheochromocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can Urol Assoc J 2009;3:89–91. 10.5489/cuaj.1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson LD. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:551–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal A, Mehrotra PK, Jain M, et al. Size of the tumor and pheochromocytoma of the adrenal gland scaled score (PASS): can they predict malignancy? World J Surg 2010;34:3022–8. 10.1007/s00268-010-0744-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg A, Pautler SE, Harle C, et al. Giant cystic pheochromocytoma containing high concentrations of catecholamines and metanephrines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:2308–9. 10.1210/jc.2011-0465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): neuroendocrine tumors: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2015:108 Updated 11 Nov 2014 www.nccn.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]