Abstract

Wobble base pairs are critical in various physiological functions and have been linked to local structural perturbations in double-helical structures of nucleic acids. We report a 1.38-Å resolution crystal structure of an antiparallel octadecamer RNA double helix in overall A conformation, which includes a unique, central stretch of six consecutive wobble base pairs (W helix) with two G·U and four rare C·A+ wobble pairs. Four adenines within the W helix are N1-protonated and wobble-base-paired with the opposing cytosine through two regular hydrogen bonds. Combined with the two G·U pairs, the C·A+ base pairs facilitate formation of a half turn of W-helical RNA flanked by six regular Watson–Crick base pairs in standard A conformation on either side. RNA melting experiments monitored by differential scanning calorimetry, UV and circular dichroism spectroscopy demonstrate that the RNA octadecamer undergoes a pH-induced structural transition which is consistent with the presence of a duplex with C·A+ base pairs at acidic pH. Our crystal structure provides a first glimpse of an RNA double helix based entirely on wobble base pairs with possible applications in RNA or DNA nanotechnology and pH biosensors.

Keywords: RNA double helix, wobble base pairing, wobble helix, adenine N1 protonation, pH-dependent structural variation

INTRODUCTION

Base-pairing in most nucleic acids follows the Watson–Crick pairing rules. Non-Watson–Crick base-pairing, however, is also prevalent and plays crucial roles for various physiological functions (Deng and Sundaralingam 2000; Masquida and Westhof 2000; Varani and McClain 2000). Among all non-Watson–Crick pairs, the G·U wobble is the most studied pair that has been shown to be highly conserved in the acceptor helix of tRNAAla, common in other tRNAs (Sprinzl et al. 1998) and rRNA (Gautheret et al. 1995), and critical for RNA–protein recognition (Hou and Schimmel 1988; McClain and Foss 1988) and splice-site selection in group I introns (Cech 1987; Strobel and Cech 1995). Among other mismatches, C·A+ wobble pairs are less frequently observed; however, they have been shown to be isosteric with and capable of substituting G·U pairs in some cases (Samuelsson et al. 1983; Doudna et al. 1989; Gautheret et al. 1995; Masquida and Westhof 2000).

G·U and C·A+ pairs are significantly different from Watson–Crick base pairs, and they present opportunities for specific recognition either by generating local irregularity of helical structure or by introducing electrostatic variations in the grooves. G·U wobble base pairs are thermodynamically favorable and require only slight adjustment in base pair λ angles to form two stable hydrogen bonds (Hunter et al. 1987; Puglisi et al. 1990). The formation of two isosteric hydrogen bonds in a C·A wobble pair, however, is not possible with bases in their standard configuration. Here, the N1(A)–O2(C) hydrogen bond can only form if either the protonation or the tautomeric state of the participating bases are changed. A first model proposes hydrogen-bond stabilization by rare amino–imino tautomers of cytosine or adenine (Saenger 1983; Hunter et al. 1986, 1987; Russo et al. 1998; Masoodi et al. 2016). Similarly, a second model suggests protonation of cytosine N3 simultaneously with a tautomeric shift in the adenine base (Supplemental Fig. S1). Cytosine N3 protonation has been invoked in U6 RNA loop structure formation in Trypanosoma brucei and Crithidia fasciculata (Huppler et al. 2002) and the DNA–triostin-A interaction (Quigley et al. 1986). However, whereas the transient formation of base pairs involving the rare enol tautomers of guanine and thymine was recently demonstrated by NMR methods (Kimsey et al. 2015), experimental proof of C·A pairs with adenine imino tautomers is lacking, to the best of our knowledge.

The most frequently invoked model for C·A mismatch formation proposes protonation of adenine N1, which would allow a second hydrogen bond to form with cytosine O2 as acceptor atom (Hunter et al. 1986, 1987). In aqueous solution, adenosine exists in three different mono-protonation states with pKa values of 3.64, −1.53, and −4.02 for N1, N7, and N3 protonation (Saenger 1983; Kapinos et al. 2011), and the protonation propensity of adenosine N1 was reported as being 96.1% over N7 and N3 protonation states (Kapinos et al. 2011). Also, adenine N1 protonation has been observed in poly(rA) fibers (Rich et al. 1961), oligo(rA) stretches in crystal structures (Gleghorn et al. 2016), and an NMR structure of poly(dA) (Chakraborty et al. 2009), allowing the oligo(A) to form either a parallel-stranded double helix (π-helix) at acidic pH or a single-stranded helical structure at neutral pH.

In addition, the presence of adenine N1 protonation in isolated or tandem C·A+ wobble base pairs is confirmed by several crystal (Hunter et al. 1986, 1987; Jang et al. 1998; Pan et al. 1998) and NMR (Puglisi et al. 1990; Durant and Davis 1999; Huppler et al. 2002) structures of different oligonucleotides. Interestingly, tandem C·A+/A+·C pairs exhibit cross-strand purine stacking due to the near 0° helical twist, which is compensated by a twist increase by 10°–15° at the adjacent Watson–Crick pairs (Jang et al. 1998), while an isolated C·A+ pair causes little helical irregularity, suggesting that neighboring base pairs are efficient in maintaining overall helical geometry when more than one C·A+ pair is present. Although several structures for base pair mismatches are available showing G·U or C·A+ wobble pairs in isolation, in tandem or with other mismatches, both wobble pairs have never been shown together in a crystal structure. Only one NMR structure of an RNA hairpin with both G·U and C·A+ pairs is available that shows these wobble pairs in isolation (Puglisi et al. 1990).

Here we present a high-resolution crystal structure of an 18-bp antiparallel RNA double helix, which includes one half helical turn of W helix, comprising six contiguous wobble base pairs at the center flanked by half turns of standard A-form RNA on either side. The W-helical stretch is formed by four C·A+ and two G·U wobble base pairs. The geometry of the novel form of RNA helix is described in detail with a focus on the central wobble pairs. In addition, pH-dependent variations in the RNA structure are probed by various biophysical methods. We suggest that the pH-dependent formation of W-helical RNA might become a valuable tool for RNA nanotechnology applications.

RESULTS

Structure analysis and crystal packing

X-ray diffraction data for the RNA, r(UGUUCUCUACGAAGAACA), were collected to maximum resolution of 1.38 Å, and a Matthews’ analysis indicated the presence of one RNA strand in the asymmetric unit. Molecular replacement with PHASER-MR (McCoy et al. 2005) oriented and positioned a partial RNA model into the unit cell with log-likelihood gain (LLG) and translation function Z-score (TFZ) of 54.4 and 5.3, respectively. One round of automated model building and refinement was performed using Autobuild wizard, which, after fitting the correct oligonucleotide sequence and refinement, yielded Rwork/Rfree of 23.7%/24.0%. Bond length and angle restraints combined with base-planarity and hydrogen-bonding restraints for base pairs were used simultaneously with anisotropic displacement factor restraints over the whole refinement process, which yielded a final Rwork/Rfree of 12.9%/15.1% (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

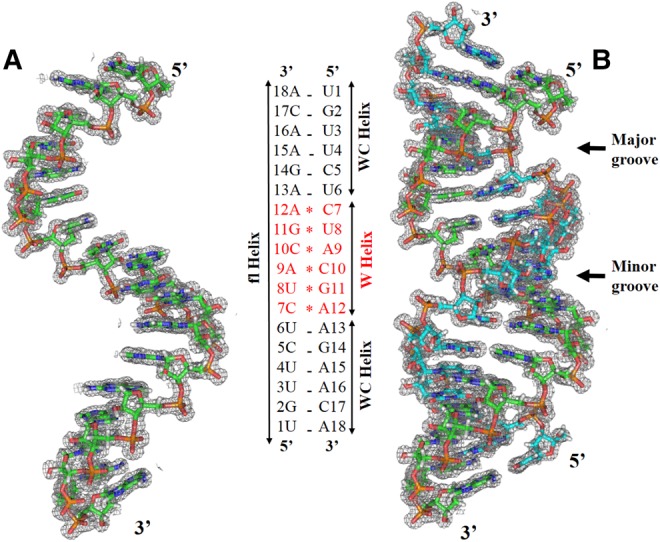

The RNA molecule crystallized in space group P6322, forming an 18-bp antiparallel RNA double helix with two identical strands related by crystallographic symmetry. These duplexes are stacked in head-to-tail fashion to generate a pseudo-continuous RNA column around the 63 screw axis along the crystallographic c-axis (Supplemental Fig. S2A). The helical stacks are stabilized by eight well-coordinated water molecules present in the minor groove at the helical junction. The eight waters are symmetrically arranged and form a hydrogen-bonding network that stabilizes the helical arrangement by forming specific hydrogen bonds with all four sugar 2′OH, N3, and O2 atoms of adenine and uridine, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

Geometry of RNA double helix

In the crystal, two RNA strands form an antiparallel double helical structure with 18 bp (Fig. 1). The helical parameters for the full-length RNA structure (fl helix) suggest that the double helix exhibits A-RNA conformation with helical periodicity of 10.96 bp, similar to canonical A-RNA, which has 11 bp per helical turn (Table 2; Schindelin et al. 1995; Olson et al. 2001). The RNA double helix can be divided into three helical segments of 6 bp each with the first and third segments (WC helix) having a total of 12 bases paired according to canonical Watson–Crick base-pairing rules, while the second helical segment (W helix) at the center contains six bases per strand paired in a noncanonical scheme (see Fig. 1). Helical parameters for the WC helix reflect A-RNA-like geometry with periodicity of 10.92 bp per turn; however, the W helix displays unique features with similarities to both A-RNA and A′-RNA. Although large local variations in helical Twist and Rise are present, the mean values of 29.09° for the helical Twist and 1.91 Å for the Rise, respectively, reflect similarities between the W helix and A-RNA, while the W helix is similar to A′-RNA in having helical periodicity of 12 bp (Supplemental Table S1; Arnott et al. 1972; Tanaka et al. 1999). This indicates that locally distorted wobble base pair repeats can be incorporated in RNA double helices with little overall distortion in helical geometry. Incorporation of maximally four noncanonical base pairs (Holbrook et al. 1991) or two wobble-base pairs present either in isolation (Hunter et al. 1986, 1987; Pan et al. 1998) or in tandem (Biswas et al. 1997; Jang et al. 1998) has been reported earlier. The structure presented here shows that up to six contiguous non-Watson–Crick base pairs may be accommodated in double-helical RNA.

FIGURE 1.

X-ray crystal structure of antiparallel RNA double helix with 2DFo-mFc difference density contoured at 1.0 σ with 1.6 Å radius of atoms. (A) The crystallographic asymmetric unit consists of a single 18-nt RNA strand. (B) Crystallographic dyad symmetry generates an RNA double helix (fl helix) that is divided into three segments of 6 bp each, abbreviated as WC, W, and WC helix. In the WC-helix segments, bases are paired in Watson–Crick geometry, while the WB helix contains six bases paired in wobble geometry.

TABLE 2.

Mean values for global helical parameters of the RNA fl helix, WC helix, and W helix

All sugars in the oligonucleotide are in C3′-endo pucker with average pseudorotation phase angle of 13.10 (±3.92)°, and all nucleosides are in anti conformation having an average glyosidic torsion angle of −162.76 (±5.64)°. Most backbone torsion angles are within the expected regions for the A conformation, having gauche (−) for α and ζ, trans for β and ε, and gauche (+) for γ and δ, with the exception of the C5 nucleoside which has both α and γ torsions in trans with 143.8° and −169.7°, respectively. Although these trans–trans conformations do not occur at every single wobble residue, they occur frequently in structures with wobble G·U or C·A+ pairs (Biswas et al. 1997; Jang et al. 1998; Pan et al. 1998).

RNA helix is stabilized by 4 C·A+ and 2 G·U wobble base pairs

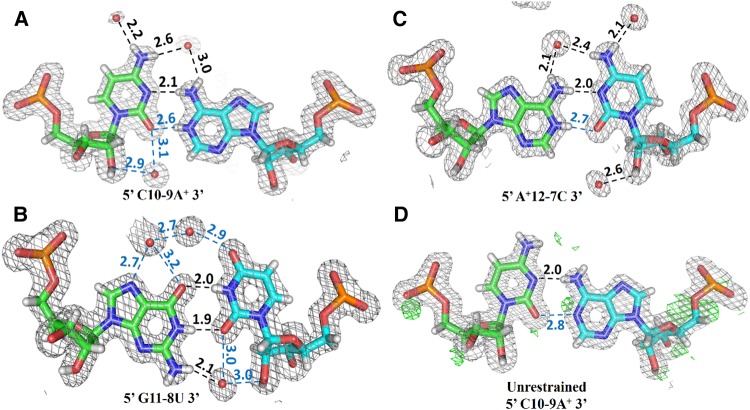

Antiparallel arrangement of r(UGUUCUCUACGAAGAACA) strands is supported by a crystallographic dyad axis perpendicular to the helix axis that passes at the A9-C10/A9-C10 base pair step and generates nine unique base pairs at either end of the helix. Six terminal base pairs forming the WC helix are stabilized by Watson–Crick base-pairing with A·U and C·G pairs, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S3). The striking feature of the RNA helix is the presence of six non-Watson–Crick base pairs at the center (W helix) with three of them (C10·9A+, G11·8U, A+12·7C) being crystallographically unique pairs. All three unique wobble pairs are depicted in Figure 2 with their water molecule coordination. All six non-Watson–Crick base pairs display clear wobble geometry, which is characterized by opposite drifts of λ angles for purines and pyrimidines and formation of two hydrogen bonds, one of which links the purine imino hydrogen and the pyrimidine carbonyl oxygen.

FIGURE 2.

2DFo-mFc electron density contoured at 1.0 σ for the three unique wobble base pairs in the WB helix. Two characteristic hydrogen bonds are formed between bases, and a third hydrogen bond is mediated by a water molecule located in the major groove. (A,C) Two unique C·A+ pairs and (B) the unique G·U pair shown with their hydration networks in both helical grooves. (D) The C·A base pair after refinement with relaxed geometric restraints. Characteristic bond-angle changes in the adenine ring and positive difference density (green) at the position of adenine H1 both indicate adenine N1 protonation. The Fo–Fc difference density is contoured at the 2.5 σ level. Hydrogen-bond distances are given in Ångstrom units with hydrogen-acceptor distances shown in black and donor-acceptor distances (N…O or O…O) in cyan.

In the W helix, all direct interbase hydrogen bonds are facilitated by the reduction in the C1′–C1′ distance to an average of 10.3 Å from 10.6 Å, as observed in Watson–Crick pairs (Rosenberg et al. 1976; Seeman et al. 1976; Olson et al. 2001). Simultaneously, the bases of a wobble pair undergo a shear movement, leading to an average −12.5° and +15° shift in λ angle for the purine and pyrimidine base, respectively (Supplemental Figure S4; Supplemental Table S2; Hunter et al. 1986; Pan et al. 1998). Both G·U pairs are organized in well-defined wobble geometry with two hydrogen bonds between O6(G)…N3(U)-H and N1(G)-H…O2(U). In C·A+ pairs, one standard hydrogen bond is formed between N3(C)…N6(A)-H, and a second hydrogen bond is formed between O2(C)…N1(A+)-H to complete the wobble arrangement. The protonation of adenine N1 (see below), facilitating formation of the second H bond is probably linked to the acidic pH 4.0 of the crystallization buffer, which is close to the pKa of adenine N1 (Saenger et al. 1975; Saenger 1983; Kapinos et al. 2011).

The unique wobble base pairs C10·9A+ and A+12·7C exhibit similar hydrogen bonding patterns as G11·8U (see Fig. 2). Minor groove water molecules interact with the 2′ hydroxyl groups of cytosine, but fail to make any direct hydrogen bond with the paired adenosine. The C·A+ pairs share with the G·U pair a unique water molecule located in the major groove, which stabilizes the RNA helix by bridging N4 to N6 of cytosine and adenine, respectively. The G11·8U pair is highly hydrated, and its hydrogen bonding potential is saturated by an integral water molecule in the minor groove, interacting with a free N2 amino group, O2 and O2′. Unlike the C·A+ base pairs, the G·U pair binds two water molecules in the major groove, which form a hydrogen bonding network with N7, O6, and O4, and with each other. Major- and minor-groove water molecules, as observed near the C·A+ base pairs, and minor-groove waters, as bound to the G·U base pair, present either in isolation or in tandem, have been shown to be instrumental in stabilizing the wobble pair and its incorporation in RNA helices (Hunter et al. 1987; Holbrook et al. 1991; Biswas and Sundaralingam 1997; Biswas et al. 1997; Pan et al. 1998; Mueller et al. 1999; Trikha et al. 1999). The novel feature of the structure presented here lies in the demonstration that extended segments of exclusively wobble-base-paired nucleotides can be accommodated in an RNA double helix with almost no difference in the hydration pattern of the individual bases.

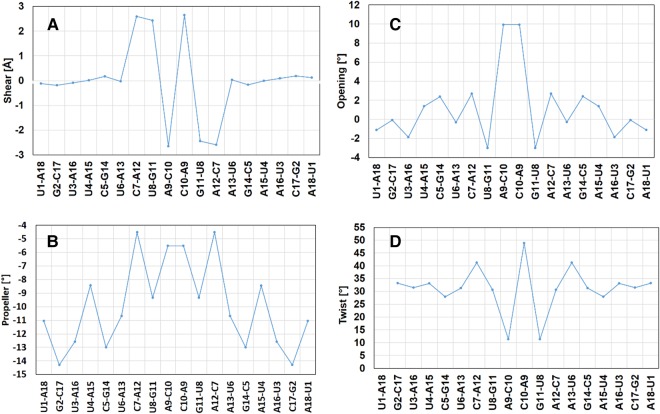

To determine conformational features of the fl helix and the central W helix, we analyzed the RNA structure with 3DNA (Supplemental Table S3; Zheng et al. 2009). The Shear parameter is generally assumed to be a characteristic indicator of wobble base pairs because of their approximately ±2 Å Shear which does not occur in Watson–Crick base pairs (Olson et al. 2001). Notably, in the central W helix, base pairs are significantly distorted with extremes of Shear of ±2.65 Å, whereas the flanking WC helix shows nonsheared base pairs (Fig. 3A). Additionally, base pairs in the W helix show significantly higher Opening accompanied by reduced Propeller distortion, which allows a sufficiently close approach of hydrogen-bonded atoms (Fig. 3B,C). Similar variations are observed in base-step Twist in the W helix, but the significant effect of individual base-pair Twist is compensated by under- and over-twisting of associated base pairs allowing the RNA helix to maintain A configuration (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Base pair parameters of the symmetric RNA double helix. Prominent variations in (A) Shear, (B) Opening, (C) Propeller, and (D) Twist steps are observed in the central wobble-base-paired W-helix segment as compared to the terminal Watson–Crick-paired A-RNA.

Wobble helix and adenine protonation

The protonation state of adenine can be inferred by measuring the internal bond angles, and the pattern of bond-angle changes may hint at protonation at a particular nitrogen in the adenine ring (Taylor and Kennard 1982; Saenger 1983; Safaee et al. 2013; Gleghorn et al. 2016). After one round of structure refinement with relaxed geometric restraints, we compared average C2–N1–C6 and C2–N3–C4 bond angles of adenines in Watson–Crick and wobble base pairs, respectively, with bond angle standards for different adenine protonation states generated either from 467 small-molecule structures retrieved from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) or computed using quantum mechanics (Table 3; Gleghorn et al. 2016). Bond angles for individual adenines in the crystal structure are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

TABLE 3.

Bond angle analysis of adenines present in the WC- and W-helical segments of the crystal structure. Corresponding bond angles for adenine in different protonation states derived from the CSD and quantum mechanics (Gleghorn et al. 2016) are given for comparison.

Upon relaxing the geometric restraints for RNA, the adenine rings in the wobble base pairs readjusted themselves in the electron density, resulting in increased C2–N1–C6 bond angles and hydrogen bond lengths. Adenine geometries in Watson–Crick base pairs did not display similar changes. In wobble base pairs only, low-level difference density appeared near the N1 position indicating its protonation (see Fig. 2D). The average C2–N1–C6 bond angle for Watson–Crick paired adenines remained at 117.39° (±0.75°) while wobble-paired adenines exhibited an increased bond angle of 125.92° (±2.71°). C2–N1–C6 bond-angle values derived from the CSD and quantum mechanics were ∼124.0° (±2.5°) and 123.4°, respectively, and, similarly, a 126.8° bond angle is reported for N1-protonated adenine in a staggered zipper poly(A) double helix (Gleghorn et al. 2016). For the crystal structure, this analysis strongly supports the model that the adenine N1 position in the W-helical center is protonated, which facilitates the formation of the O2(C)…N1(A+)-H hydrogen bond. Additionally, in the RNA helix the average C2–N3–C6 bond angle for Watson–Crick paired adenine is 110.44° (±2.65°), while it moderately increases to 114.52° (±1.19°) in wobble-paired adenines. This increment, however, is too small to suggest adenine N3 protonation when compared to the CSD or quantum mechanics–based standards of 117.3° (±0.6°) and 116.9°.

To rule out the possibility of N3-protonated cytosine-mediated wobble bond formation (see Supplemental Fig. S1C), we also compared the C2–N3–C4 bond angles in restrained and unrestrained RNA structures. Upon relaxing the geometric restraints, the average C2–N3–C4 bond angle in wobble base pairs did not increase to ∼125° as expected for N3-protonated cytosine (Clowney et al. 1996), but instead it reduced to 114.57° (±0.57°) from 118.94° (±0.40°), clearly ruling out protonation at cytosine N3. The average C2–N3–C4 bond angle in Watson–Crick pairs did not significantly change upon removing the geometric restraints.

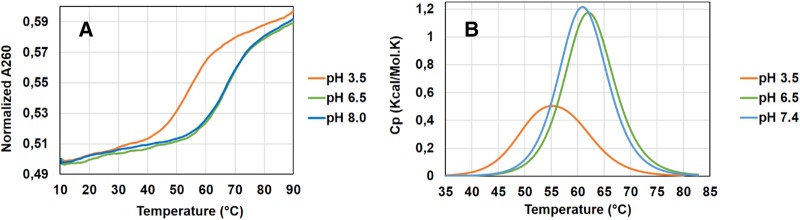

pH-dependent UV thermal melting

To test our hypothesis that formation of the 18-bp RNA duplex observed in the crystal was facilitated by adenine N1 protonation in its central W-helix segment, we examined if any pH-induced structural transition in the RNA can be observed in thermal melting experiments at different pH values. UV spectra were recorded at 260 nm and pH values of 3.5, 6.5, and 8.0 to monitor structural transitions upon change from acidic to slightly basic medium. One representative out of three experiments is shown in Figure 4A.

FIGURE 4.

pH-dependent variation of physical and thermodynamic properties of RNA. (A) UV thermal melting curves at pH 3.5, 6.5, and 8.0 (orange, green, and blue) indicate a pH-dependent structural transition in RNA. (B) RNA thermal melting curves recorded with differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) at pH 3.5, 6.5, and 8.0.

Upon sample heating, all spectra showed a hyperchromic transition in UV absorption, suggesting the dissociation from double-helical to single-stranded RNA. We observed that pH change from 3.5 to 6.5 raised the RNA melting temperature from ∼55°C to ∼67°C. Notably, no change in melting temperature was observed for a further pH increase from 6.5 to 8.0. The significant change in Tm may be linked to different RNA conformations existing at near neutral and acidic pH. It is consistent with the existence of neutral adenine bases at near neutral or basic pH, which could destabilize the central wobble base pairs, inducing a different RNA structure. Moreover, a higher Tm for the RNA at neutral pH indicates that the configuration present under physiological conditions is thermodynamically favored over the double-helical structure with central W-helix segment observed in crystals grown at low pH.

Differential scanning calorimetry

To further determine the thermodynamic properties associated with different conformations observed at different pH values, DSC experiments were performed with RNA elements buffered at pH 3.5, 6.5, and 7.4. DSC profiles and thermodynamic parameters of RNA thermal melting are shown in Figure 4B. According to DSC analysis, the melting temperature is 55.6°C, 62.1°C, and 61.0°C at pH 3.5, 6.5, and 7.4, respectively, which is in good agreement with Tm values calculated by UV melting experiments. In particular, the DSC analysis confirms that the RNA behaves similarly at pH 6.5 and 7.4, whereas the melting transition at acidic pH occurs at a different temperature. The higher Tm of the RNA at neutral pH is in accordance with a higher energy release upon melting transition. The enthalpy change of RNA is ∼73 kcal/mol near physiological pH and ∼64 kcal/mol for the double-helical structure existing at acidic pH, suggesting the existence of different initial RNA structures (Table 4). Taken together with the UV melting experiment, the DSC data confirm that different RNA structures exist at neutral and acidic pH for a sequence that permits formation of a central W helix with N1-protonation of adenine bases.

TABLE 4.

Thermodynamic parameters from DSC measurements of the RNA at pH values between 3.5 and 7.4

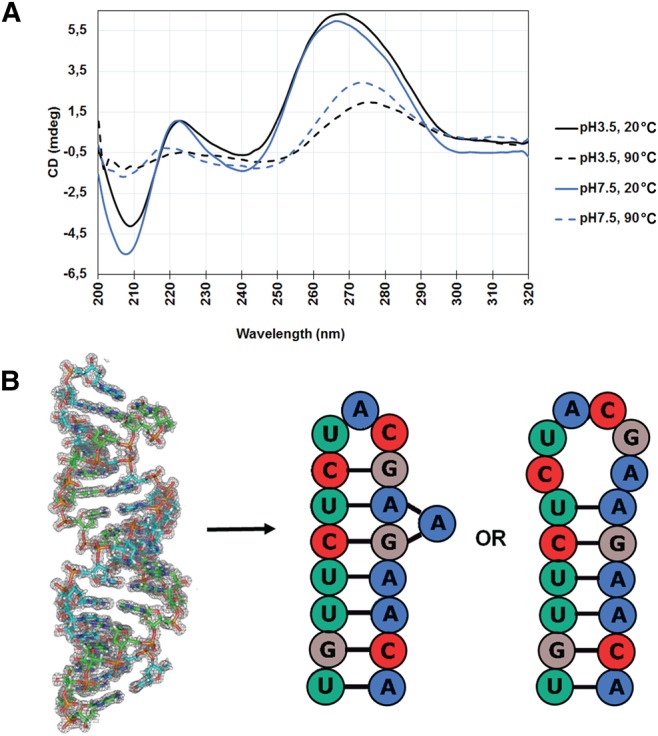

pH-induced structural changes probed by CD melting

Circular dichroism is extremely sensitive to nucleic-acid conformation and can provide valuable information about its structure (Ivanov et al. 1973; Johnson 1990; Woody 1995). We probed the structural differences in RNA at different pH values by recording CD melting transitions at pH 3.5 and 7.5. Average CD spectra from three independent experiments for both pH values at 20°C and 90°C, respectively, representing the folded and melted state of RNA, are shown in Figure 5, while CD spectra and ellipticity changes with temperature are shown in Supplemental Figure S5.

FIGURE 5.

Structural asymmetries of RNA element at different pH are probed by CD melting spectra. (A) An overlay of CD spectra at 20°C (solid line) and 90°C (dotted line) for RNA elements is represented at pH 3.5 (black) and 7.5 (blue). (B) The physiological structure of the RNA element is most likely an A-RNA stem–loop with either tri- or hexa-loop and not the double-helical structure observed at acidic pH.

Clearly, at both pH values, the RNA exhibits CD spectra characteristic of the A conformation with maximum at ∼265 nm and minimum at ∼210 nm (Johnson 1990; Chauca-Diaz et al. 2015). Upon heating RNA to 90°C, bases become unstacked, which is reflected by disappearance of the peak at 210 nm, while the peak at ∼265 nm is reduced and shifted to ∼274 nm (Causley and Johnson 1982; Newbury et al. 1996). The peak at ∼210 nm is known to be related to the intrastrand interactions in RNA duplexes (Gray et al. 1981; Newbury et al. 1996), and our CD spectra show a significant increase in peak intensity at 210 nm at pH 7.5, suggesting extensive intrastrand interactions in the RNA. Moreover, we also observe a minor negative peak at ∼240 nm in the spectra, which is indicative of the presence of single-stranded RNA at pH 7.5 (Newbury et al. 1996; Chauca-Diaz et al. 2015).

All CD observations are in agreement with RNA acquiring a highly stable stem–loop structure with unprotonated adenines at physiological pH, forming extensive intrastrand interactions as compared to the double-helical structure, and unpaired bases in the loop (see Fig. 5). Our CD data are strongly supported by a SHAPE (selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension) analysis (Wilkinson et al. 2006) for an oligonucleotide with a very similar sequence, r(UGUUCUCUACGAAGAACU), which also acquires a tri-loop RNA stem–loop structure at physiological pH (Mino et al. 2015).

DISCUSSION

We present a 1.38-Å resolution crystal structure of an 18-nt-long antiparallel RNA double helix formed in an acidic environment. The overall structure exhibits A-RNA conformation and is clearly divided into three helical segments of 6 bp each, denoted as WC, W, and WC helix. The W helix represents a unique and novel helical form of RNA that is completely based on wobble base pairing and consists of four C·A+ and two G·U wobble base pairs. The W helix exhibits overall helical similarity with A-RNA (Schindelin et al. 1995; Olson et al. 2001), while it resembles A′-RNA in having 12 bp per turn (Arnott et al. 1972; Tanaka et al. 1999). In both G·U wobble pairs of the W-helical segment, guanine is shifted toward the minor groove and interacts with O2 and O2′ via a water molecule similar to isolated G·U pairs or tandem G·U pairs in motifs I and II of ribosomal RNAs (Biswas and Sundaralingam 1997; Biswas et al. 1997). The C·A wobble pairs are formed as C·A+ pairs following N1 protonation of adenines in the W helix, which is indicated by difference electron density and adenine bond angles after unrestrained structure refinement that agree with bond-angle standards from adenine bases with N1 protonation (Taylor and Kennard 1982; Safaee et al. 2013; Gleghorn et al. 2016). C·A+ base pairs in previous RNA crystal structures, either in isolation (Pan et al. 1998) or in tandem (Jang et al. 1998), resulted in RNA bending of ∼20°. The present structure of a W-helical segment with flanking A-RNA does not show any significant bending at the base-pair steps involving C·A+, resulting in a straight helical half turn of RNA.

An RNA structure with tandem C·A+ pairs in a CA+ dinucleotide step exhibited cross-strand purine stacking (Supplemental Fig. S6A) accompanied by helical over-winding toward the neighboring Watson–Crick pairs (Jang et al. 1998), while isolated C·A+ pairs were incorporated in A-form RNA without much helical perturbations (Hunter et al. 1987; Pan et al. 1998). In the presented structure, however, tandem C·A+ pairs in an A+C dinucleotide step are stacked almost parallel (Supplemental Fig. S6B) with under-winding of neighboring pairs. Although helical parameters, in particular the base pair Twist, in the central W segment show strong fluctuations, their mean values remain in the A-helix regime. Overall, we present a novel RNA structure, the W helix, in which six consecutive wobble base pairs are incorporated in standard A-form RNA, extending the range of RNA conformations observed until now.

Importantly, we observed that the studied oligoribonucleotide exhibits significant differences in thermal stability at different pH values as probed by UV and DSC thermal melting experiments. In both UV melting and DSC analysis, we found that the thermodynamic properties of RNA varied between acidic pH of 3.5 and pH 6.5, which is consistent with adenine-N1 protonation at acidic pH (Saenger 1983; Kapinos et al. 2011). We conclude that the observed differences in the melting behavior result from adenine protonation at low pH. The adenine protonation state remains unchanged between pH 6.5 and 8.0, therefore we observe no differences in thermodynamic properties of RNA in this pH regime. Moreover, the significant difference in the enthalpic contribution to the melting transition suggests that unfolding follows different routes at different pH, consistent with the existence of different initial RNA structures. Comparative analyses of CD spectra at different pH values point to the existence of either a tri-loop (Mino et al. 2015) or a hexa-loop (Zuker 2003) RNA stem–loop structure, which acquires a double-helical wobble-base-paired RNA structure due to protonation of the central adenines at low pH.

As we have demonstrated that the RNA oligonucleotide exists in two stable conformations at different pH values, we propose that this molecule, as well as similar RNA elements with a propensity for forming W-helical structures with C·A+ base pairs, may be useful tools as pH biosensors and in RNA nanotechnology applications (Yan 2004; Guo 2010; Yu et al. 2015; Amodio et al. 2016). Adenine-N1 protonation occurs under acidic conditions and seems to be nonphysiological. Previous reports, however, suggest that microscopic pKa change could lead to formation of C·A+ pairs in cells and influence RNA cleavage by leadzymes (Legault and Pardi 1994, 1997) and a hairpin ribozyme (Cai and Tinoco 1996). A C·A+ pair can also substitute for G·U in the P1 helix in group I introns. We suggest that similar structural changes in the RNA element studied here might occur in cells, as a result of microscopic pKa change, in order to regulate the expression of downstream immune response factors by endoribonuclease Regnase1. However, no such report on RNA structural change has been published so far.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide crystallization

The HPLC-purified oligonucleotide r(UGUUCUCUACGAAGAACA) corresponding to a highly conserved stem–loop region in the 3′ UTR of human interleukin (IL)-6 mRNA was purchased from Eurofins Genomics (Berlin, Germany) and dissolved in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 50 mM KCl to 1 mM concentration. RNA was reannealed by heating at 90°C for 10 min followed by snap-cooling on ice for 5 min and then diluted in suitable reaction buffer before experiments. Crystals were obtained during co-crystallization trials of RNA oligonucleotide and a catalytically inactive mutant of the mouse ribonuclease ZC3H12C mixed in a 2:1 molar ratio. A total of 0.2 µL of protein–RNA complex in 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 20 µM ZnSO4, 0.5 mM MgCl2 was mixed with 0.2 µL of 20% PEG 6000, 1.0 M LiCl, 0.1 M citric acid (pH 4.0) at 4°C using sitting-drop vapor diffusion technique, and rod-shaped crystals were harvested after ∼75 d, soaked in reservoir solution with 20% ethylene glycol before flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. Mixing equal volumes of solutions of the protein–RNA complex and the crystallization buffer as above yields a solution with a pH between 4.4 and 4.5.

X-ray data collection, structure determination, and refinement

X-ray diffraction data were collected at beamline 14.1 of the BESSY II synchrotron operated by Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (Mueller et al. 2012) at a wavelength of 0.9184 Å. Initial indexing and data collection strategy were determined by iMOSFLM (Battye et al. 2011), and a complete X-ray data set was processed with XDSAPP (Krug et al. 2012). Since we expected the RNA to form a stem–loop structure, we used the 5 bp stem of pre-let-7f-1 RNA (PDB entry 3TS0) as a search model (Nam et al. 2011) for molecular replacement using the PHASER-MR program (McCoy et al. 2005). Autobuilding of the initial model was performed with Phenix (Adams et al. 2010). Canonical hydrogens were generated by Phenix.reduce (Word et al. 1999) and included in the refinement as riding hydrogens. The graphics program WinCoot (Emsley et al. 2010) was used for model building and visualization, and all refinements were performed by Phenix.Refine or CCP4 Refmac5 (Murshudov et al. 1997). Molecular drawings were generated with the PyMOL molecular graphics system (Version 1.7.0.5, Schrodinger, LLC), and Web 3DNA (Zheng et al. 2009) was used to analyze the structure. Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the RNA double helix were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 5NXT.

UV thermal denaturation

RNA UV thermal melting experiments were performed at three different pH values in reaction buffers (i) 25 mM citric acid (pH 3.5), 200 mM LiCl, 1 mM MgSO4, (ii) 25 mM citric acid (pH 6.5), 200 mM LiCl, 1 mM MgSO4, or (iii) 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM LiCl, 1 mM MgSO4, using a Chirascan CD spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK) with 1-mm pathlength cuvette. RNA was diluted to 16 µM in reaction buffers and incubated at 4°C overnight before measurements. Denaturation curves were acquired by recording absorbance at 260 nm in 0.5°C steps, while temperature was increased from 10°C to 90°C at a rate of 1°C/min. Data were analyzed and processed with the pro-data Chirascan software (Applied Photophysics). The absorbance of samples was normalized to 0.5°C at 10°C and plotted using Excel.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC experiments were performed with a NanoDSC instrument (TA Instruments, Eschborn, Germany) with RNA at a concentration of 100 µM dissolved in reaction buffers (i) 10 mM citric acid (pH 3.5), 50 mM LiCl, (ii) 10 mM citric acid (pH 6.5), 50 mM LiCl, or (iii) 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 50 mM LiCl. RNA samples were incubated at 4°C overnight before measurements. The calorimetric data for RNA were obtained between 10°C and 100°C at a scan rate of 1°C/min. Data were corrected for buffer scan and analyzed with a two-state scaled model with NanoAnalyze software (TA Instruments). Results from two independent experiments were averaged, and errors were calculated as ±SD.

RNA circular dichroism (CD) melting

All RNA CD melting experiments were carried out using a Chirascan CD spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics) and a 1-mm pathlength cuvette. RNA was dissolved at a concentration of 16 µM in reaction buffer (i) 10 mM citric acid (pH 3.5), 50 mM NaCl, or (ii) potassium phosphate (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and incubated overnight at 4°C. The CD spectra between 320 and 200 nm for each 1°C temperature increase were recorded in 1.5 nm steps between 20 and 90°C at a ramp rate of 0.5°C/min. Three independent experiments were performed at pH 3.5 and 7.4, and spectra were corrected for buffer scan, smoothed with a five-point algorithm, averaged using the Pro-data Chirascan software (Applied Photophysics), and plotted using Excel.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the beamline support by the staff of Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin für Materialien und Energie at BESSY and Yvette Roske for assistance with the diffraction data collection.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.064048.117.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amodio A, Adedeji AF, Castronovo M, Franco E, Ricci F. 2016. pH-controlled assembly of DNA tiles. J Am Chem Soc 138: 12735–12738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnott S, Hukins DW, Dover SD. 1972. Optimised parameters for RNA double-helices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 48: 1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. 2011. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67: 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R, Sundaralingam M. 1997. Crystal structure of r(GUGUGUA)dC with tandem G·U/U·G wobble pairs with strand slippage. J Mol Biol 270: 511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas R, Wahl MC, Ban C, Sundaralingam M. 1997. Crystal structure of an alternating octamer r(GUAUGUA)dC with adjacent G·U wobble pairs. J Mol Biol 267: 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Tinoco I Jr. 1996. Solution structure of loop A from the hairpin ribozyme from tobacco ringspot virus satellite. Biochemistry 35: 6026–6036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causley GC, Johnson WC Jr. 1982. Polynucleotide conformation from flow dichroism studies. Biopolymers 21: 1763–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR. 1987. The chemistry of self-splicing RNA and RNA enzymes. Science 236: 1532–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S, Sharma S, Maiti PK, Krishnan Y. 2009. The poly dA helix: a new structural motif for high performance DNA-based molecular switches. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 2810–2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauca-Diaz AM, Choi YJ, Resendiz MJ. 2015. Biophysical properties and thermal stability of oligonucleotides of RNA containing 7,8-dihydro-8-hydroxyadenosine. Biopolymers 103: 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowney L, Jain SC, Srinivasan AR, Westbrook J, Olson WK, Berman HM. 1996. Geometric parameters in nucleic acids: nitrogenous bases. J Am Chem Soc 118: 509–518. [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Sundaralingam M. 2000. Synthesis and crystal structure of an octamer RNA r(guguuuac)/r(guaggcac) with G·G/U·U tandem wobble base pairs: comparison with other tandem G·U pairs. Nucleic Acids Res 28: 4376–4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna JA, Cormack BP, Szostak JW. 1989. RNA structure, not sequence, determines the 5′ splice-site specificity of a group I intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 7402–7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant PC, Davis DR. 1999. Stabilization of the anticodon stem–loop of tRNALys,3 by an A+-C base-pair and by pseudouridine. J Mol Biol 285: 115–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautheret D, Konings D, Gutell RR. 1995. G·U base pairing motifs in ribosomal RNA. RNA 1: 807–814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleghorn ML, Zhao J, Turner DH, Maquat LE. 2016. Crystal structure of a poly(rA) staggered zipper at acidic pH: evidence that adenine N1 protonation mediates parallel double helix formation. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 8417–8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DM, Liu JJ, Ratliff RL, Allen FS. 1981. Sequence dependence of the circular dichroism of synthetic double-stranded RNAs. Biopolymers 20: 1337–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P. 2010. The emerging field of RNA nanotechnology. Nat Nanotechnol 5: 833–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook SR, Cheong C, Tinoco I Jr, Kim SH. 1991. Crystal structure of an RNA double helix incorporating a track of non-Watson-Crick base pairs. Nature 353: 579–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YM, Schimmel P. 1988. A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature 333: 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WN, Brown T, Anand NN, Kennard O. 1986. Structure of an adenine-cytosine base pair in DNA and its implications for mismatch repair. Nature 320: 552–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WN, Brown T, Kennard O. 1987. Structural features and hydration of a dodecamer duplex containing two C.A mispairs. Nucleic Acids Res 15: 6589–6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppler A, Nikstad LJ, Allmann AM, Brow DA, Butcher SE. 2002. Metal binding and base ionization in the U6 RNA intramolecular stem–loop structure. Nat Struct Biol 9: 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov VI, Minchenkova LE, Schyolkina AK, Poletayev AI. 1973. Different conformations of double-stranded nucleic acid in solution as revealed by circular dichroism. Biopolymers 12: 89–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SB, Hung LW, Chi YI, Holbrook EL, Carter RJ, Holbrook SR. 1998. Structure of an RNA internal loop consisting of tandem C-A+ base pairs. Biochemistry 37: 11726–11731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WC. 1990. Numerical data and functional relationships in science and technology. In Landolt-Bornstein. Group VII: Biophysics 1c. [Google Scholar]

- Kapinos LE, Operschall BP, Larsen E, Sigel H. 2011. Understanding the acid-base properties of adenosine: the intrinsic basicities of N1, N3 and N7. Chem Eur J 17: 8156–8164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimsey IJ, Petzold K, Sathyamoorthy B, Stein ZW, Al-Hashimi HM. 2015. Visualizing transient Watson-Crick-like mispairs in DNA and RNA duplexes. Nature 519: 315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krug M, Weiss MS, Heinemann U, Mueller U. 2012. XDSAPP: a graphical user interface for the convenient processing of diffraction data using XDS. J Appl Crystallogr 45: 568–572. [Google Scholar]

- Legault P, Pardi A. 1994. In situ probing of adenine protonation in RNA by 13C NMR. J Am Chem Soc 116: 8390–8391. [Google Scholar]

- Legault P, Pardi A. 1997. Unusual dynamics and pKa shift at the active site of a lead-dependent ribozyme. J Am Chem Soc 119: 6621–6628. [Google Scholar]

- Masoodi HR, Bagheri S, Abareghi M. 2016. The effects of tautomerization and protonation on the adenine-cytosine mismatches: a density functional theory study. J Biomol Struct Dyn 34: 1143–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masquida B, Westhof E. 2000. On the wobble GoU and related pairs. RNA 6: 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClain WH, Foss K. 1988. Changing the identity of a tRNA by introducing a G-U wobble pair near the 3′ acceptor end. Science 240: 793–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. 2005. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 61: 458–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino T, Murakawa Y, Fukao A, Vandenbon A, Wessels HH, Ori D, Uehata T, Tartey S, Akira S, Suzuki Y, et al. 2015. Regnase-1 and Roquin regulate a common element in inflammatory mRNAs by spatiotemporally distinct mechanisms. Cell 161: 1058–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller U, Schübel H, Sprinzl M, Heinemann U. 1999. Crystal structure of acceptor stem of tRNAAla from Escherichia coli shows unique G·U wobble base pair at 1.16 Å resolution. RNA 5: 670–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller U, Darowski N, Fuchs MR, Förster R, Hellmig M, Paithankar KS, Pühringer S, Steffien M, Zocher G, Weiss MS. 2012. Facilities for macromolecular crystallography at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin. J Synchrotron Radiat 19: 442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. 1997. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr D53: 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam Y, Chen C, Gregory RI, Chou JJ, Sliz P. 2011. Molecular basis for interaction of let-7 microRNAs with Lin28. Cell 147: 1080–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newbury SF, McClellan JA, Rodger A. 1996. Spectroscopic and thermodynamic studies of conformational changes in long, natural messenger ribonucleic acid molecules. Anal Commun 33: 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Olson WK, Bansal M, Burley SK, Dickerson RE, Gerstein M, Harvey SC, Heinemann U, Lu XJ, Neidle S, Shakked Z, et al. 2001. A standard reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry. J Mol Biol 313: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B, Mitra SN, Sundaralingam M. 1998. Structure of a 16-mer RNA duplex r(GCAGACUUAAAUCUGC)2 with wobble C·A+ mismatches. J Mol Biol 283: 977–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi JD, Wyatt JR, Tinoco I Jr. 1990. Solution conformation of an RNA hairpin loop. Biochemistry 29: 4215–4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley GJ, Ughetto G, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Wang AHJ, Rich A. 1986. Non-Watson-Crick G·C and A·T base pairs in a DNA-antibiotic complex. Science 232: 1255–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich A, Davies DR, Crick FHC, Watson D. 1961. The molecular structure of polyadenylic acid. J Mol Biol 3: 71–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg JM, Seeman NC, Day RO, Rich A. 1976. RNA double-helical fragments at atomic resolution. II. The crystal structure of sodium guanylyl-3′,5′-cytidine nonahydrate. J Mol Biol 104: 145–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo N, Toscano M, Grand A, Jolibois F. 1998. Protonation of thymine, cytosine, adenine, and guanine DNA nucleic acid bases: theoretical investigation into the framework of density functional theory. J Comput Chem 19: 989–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Saenger W. 1983. Principles of nucleic acids structure. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Saenger W, Riecke J, Suck D. 1975. A structural model for the polyadenylic acid single helix. J Mol Biol 93: 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaee N, Noronha AM, Rodionov D, Kozlov G, Wilds CJ, Sheldrick GM, Gehring K. 2013. Structure of the parallel duplex of poly(A) RNA: evaluation of a 50 year-old prediction. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 52: 10370–10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson T, Axberg T, Boren T, Lagerkvist U. 1983. Unconventional reading of the glycine codons. J Biol Chem 258: 13178–13184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin H, Zhang M, Bald R, Furste JP, Erdmann VA, Heinemann U. 1995. Crystal structure of an RNA dodecamer containing the E.coli Shine-Dalgarno sequence. J Mol Biol 249: 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman NC, Rosenberg JM, Suddath FL, Kim JJ, Rich A. 1976. RNA double-helical fragments at atomic resolution. I. The crystal and molecular structure of sodium adenylyl-3′,5′-uridine hexahydrate. J Mol Biol 104: 109–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzl M, Horn C, Brown M, Ioudovitch A, Steinberg S. 1998. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel SA, Cech TR. 1995. Minor groove recognition of the conserved G·U pair at the Tetrahymena ribozyme reaction site. Science 267: 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Fujii S, Hiroaki H, Sakata T, Tanaka T, Uesugi S, Tomita K, Kyogoku Y. 1999. A′-form RNA double helix in the single crystal structure of r(UGAGCUUCGGCUC). Nucleic Acids Res 27: 949–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R, Kennard O. 1982. The molecular structures of nucleosides and nucleotides. 1. The influence of protonation on the geometries of nucleic acid constituents. J Mol Struct 78: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Trikha J, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 1999. Crystal structure of a 14 bp RNA duplex with non-symmetrical tandem G·U wobble base pairs. Nucleic Acids Res 27: 1728–1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani G, McClain WH. 2000. The G·U wobble base pair. A fundamental building block of RNA structure crucial to RNA function in diverse biological systems. EMBO Rep 1: 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KA, Merino EJ, Weeks KM. 2006. Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nat Protoc 1: 1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody RW. 1995. Circular dichroism. Methods Enzymol 246: 34–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word JM, Lovell SC, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. 1999. Asparagine and glutamine: using hydrogen atom contacts in the choice of side-chain amide orientation. J Mol Biol 285: 1735–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H. 2004. Materials science. Nucleic acid nanotechnology. Science 306: 2048–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Liu Z, Jiang W, Wang G, Mao C. 2015. De novo design of an RNA tile that self-assembles into a homo-octameric nanoprism. Nat Commun 6: 5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Lu XJ, Olson WK. 2009. Web 3DNA—a web server for the analysis, reconstruction, and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res 37: W240–W246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.