Abstract

Aim

The purpose of the present study was to identify risk factors associated with a complicated hospital course in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

Methods

A total of 335 overdose patients were retrospectively studied in the surgical and medical intensive care unit of an academic tertiary hospital. Factors possibly associated with a complicated hospital course were evaluated. Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation, prolonged hospitalization, or death.

Results

Of the 335 overdose patients, 93 (27.8%) had a complicated hospital course. Complicated hospital course was found to be associated with a high number of ingested pills (median, 135 [interquartile range, 78–240] versus 84 [53–134] tablets, P < 0.0001), low Glasgow Coma Scale score on admission (7 [3–11] versus 13 [8–15], P < 0.0001), and a high serum lactate level on admission (1.8 [1.0–3.0] versus 1.4 [0.9–2.0] mg/dL, P < 0.01) on univariate analysis of these factors in patients with and without a complicated hospital course. The independent risk factors for a complicated hospital course identified on multivariate analysis were a high number of ingested pills (≥100 tablets), low admission Glasgow Coma Scale score (<9), and high serum lactate on admission (≥2.0 mg/dL). The probability of a complicated hospital course for patients with 0, 1, 2, or all 3 independent risk factors were 7%, 22%, 40%, and 81%, respectively.

Conclusion

The total number of ingested pills, admission Glasgow Coma Scale score, and serum lactate level on admission are predictive of a complicated hospital course in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

Keywords: Complications, drug overdose, lactate, triage, toxicology/poisoning

Introduction

Drug overdose is an increasingly frequent cause of intensive care admission in Japan.1 Some overdose patients are brought to small‐ to medium‐sized hospitals rather than tertiary care centers for treatment. Patients are brought to tertiary hospitals for intensive care unit (ICU) admission because of abnormal vital signs or ingestion of a significant amount of drugs. However, overdose patients are sometimes brought to tertiary hospitals by paramedics because of an unwillingness of other hospitals to manage these patients. Unnecessary ICU admission of stable overdose patients places a burden on the ICU and sometimes causes patient overflow. Thus, solutions are needed to address this issue.

Most overdose patients admitted to the ICU are discharged within a few days without any complications,1 but some experience a complicated hospital course (CHC) with the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, prolonged intubation and/or hospitalization, resulting in death. Patients at risk of CHC require management in the ICU, whereas others should be triaged to smaller hospitals. Methods to identify overdose patients at risk of CHC would be useful not only for paramedic triage but also for evaluation of clinical severity by physicians.

In Tokyo, a “50 tablets rule” exists that is widely used by paramedics for triaging overdose patients. The rule states that overdose patients who ingested more than 50 tablets should be triaged to tertiary care hospitals. This is based on an observational study carried out in Japan that reported relatively high intubation rates in overdose patients who ingested more than 50 tablets.2 However, there have been arguments against the use of this rule.

To date, no consensus exists on the best method for identifying overdose patients who are at high risk of CHC. In the present study, we identified factors that predispose overdose patients to CHC with the occurrence of significant complications.

Patients and Methods

Setting and study group

Aretrospective observational study was carried out to examine cases of overdose managed in the surgical and medical ICU of Kyorin University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The medical records of consecutive overdose patients admitted to the ICU from January 2010 to December 2012 were reviewed. The following cases were excluded from analysis: ingestion of poisonous substances other than pharmaceutical drugs; severe trauma; significant pre‐existing comorbidities; and those without information on drug type, amount ingested, or lactate level on admission.

Data analysis

The following patient data were analyzed: demographics (age and sex); past medical history; details of drug ingestion (time interval between ingestion and admission, drug types, variety of drug, and total number of ingested pills); clinical status on admission (Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS] score, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation by pulse oxymetry, and serum lactate); management (intubation, gastric lavage, administration of activated charcoal, hemodialysis, and hemofiltration); complications (pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy); and major outcomes (ventilator days, length of ICU stay, and survival). The total number of ingested pills represented the amount of drugs ingested instead of the weight of ingested drugs.

Definitions

In this study, pneumonia was defined as present in a patient who showed symptoms and signs of acute lower respiratory tract infection plus infiltrates seen on a chest radiograph, with the absence of an alternative diagnosis. Rhabdomyolysis was also defined as present when the creatinine kinase level was higher than the normal range in our hospital (>166 IU/L). Furthermore, decubitus ulcer and nerve palsy were defined as thinning or defect of the skin with signs of local inflammation due to mechanical pressure, and an impaired motor and/or sensory function of the nerve requiring any kind of treatment, respectively. Psychiatric diseases were defined as mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, personality disorder, and others, which were mainly treated by psychiatrists and had been diagnosed before current admission. Minor mental states such as insomnia were not included among psychiatric diseases.

Management

Patients with a low conscious level of a GCS score <9 and those at risk of aspiration were intubated. Standard treatment for most patients included forced diuresis, gastric lavage, activated charcoal, and laxatives. Repeated activated charcoal or blood purification techniques were used for selected patients as necessary. Treatments for complications were as follows: antibiotics and prolonged respiratory care when needed for pneumonia; increasing infusion volume to increase urine output for rhabdomyolysis; irrigation and dressing for decubitus ulcer; and relieving pressure to nerves and vitamin B12 for nerve palsy.

Complicated hospital course

Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation (≥3 days), prolonged hospitalization (≥5 days), or death during an ICU admission for drug overdose.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as median and interquartile ranges unless otherwise stated. Univariate analyses were carried out using the Mann–Whitney U‐test and χ2‐test. Multivariate analyses were carried out using multiple logistic regression analysis. Sensitivity and specificity curves associated with a CHC were examined to determine the optimal cut‐off value for each independent risk factor. A clinically relevant value close to the point at which sensitivity and specificity curves crossed was chosen as an optimal cut‐off value for each independent risk factor, as the cut‐off point was generally considered to be optimal for balancing the sensitivity and specificity of a test.3 All analyses were carried out using StatFlex 6 (Artec Inc., Osaka, Japan). A P‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of study group

Of 5590 ICU admissions between January 2010 and December 2012, 538 were due to acute drug overdose. A total of 335 cases were analyzed after disqualifying 203 that met the exclusion criteria. Past medical history was available in only 308 patients, and the time interval between ingestion and hospital admission was documented in only 233 patients. As shown in Table 1, overdose patients were predominantly female, and most (84.5%) had a history of psychiatric disease. The median total number of pills ingested was 95 (56–156) and the median time elapsed between ingestion and admission was 3.0 (2.0–5.0) h. The GCS score at admission was 12 (7–14) and serum lactate concentration was 1.5 (0.9–2.3) mg/dL.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 34 (27–44) |

| Gender, male/female | 68/267 |

| Psychiatric diseases | |

| Yes | 283 (84.5%) |

| Depression † | 141 (42.1%) |

| Schizophrenia † | 54 (16.1%) |

| Personality disorder † | 47 (14.5%) |

| Others † | 92 (27.5%) |

| No | 25 (7.5%) |

| Unknown | 27 (8.1%) |

| Drug | |

| Number of varieties (kinds) | 4 (2–5) |

| Total number of pills (tablets) | 95 (56–156) |

| Time after ingestion, ‡ h | 3.0 (2.0–5.0) |

| Data on admission | |

| GCS score | 12 (7–14) |

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 85 (75–105) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 110 (100–125) |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 99 (98–100) |

| Serum lactate, mg/dL | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) |

Data were expressed as median (interquartile range). †Each psychiatric disease was counted repeatedly. ‡n = 233.

Type of ingested drugs

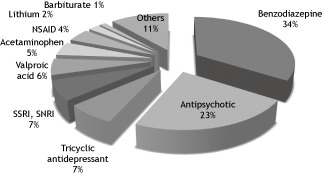

The main types of drug ingested by each patient (i.e., the drug with the largest quantity of ingested pills) are shown in Figure 1. Benzodiazepine was the most common (34%), followed by antipsychotic (23%), tricyclic antidepressant (7%), and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (7%).

Figure 1.

Main types of drug ingested by overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit of Kyorin University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan from January 2010 to December 2012 (n = 335). The drug with the largest quantity of ingested pills was shown in each case. NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Treatment, complications, and outcomes

Table 2 shows the treatment, complications, and outcomes of overdose patients admitted to the ICU. Most patients (85.4%) received standard treatment (see “Patients and Methods” section) whereas selected patients received repeated active charcoal or hemodialysis (5.7% and 2.7%, respectively). Intubation was carried out in 146 patients (43.6%) and the median duration of ventilation was 1 (1–2) days. Twenty‐three patients (6.9%) required prolonged intubation for ≥3 days. The numbers of patients who suffered from complications of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcers, and nerve palsy were 48 (14.3%), 36 (10.7%), 4 (1.2%), and 2 (0.6%), respectively. The median duration of hospitalization was 2 (2–3) days for most patients but 53 (15.8%) patients required prolonged hospitalization of ≥5 days. Three patients (0.9%) died due to cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival, respiratory failure secondary to severe pneumonia, and severe sepsis with multiple organ failure. Ninety‐three patients (27.8%) experienced CHC.

Table 2.

Treatments, complications, and outcomes in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit of Kyorin University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan from January 2010 to December 2012 (n = 335)

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Treatment for overdose | |

| Standard treatment † | 286 (85.4%) |

| Repeated charcoal | 19 (5.7%) |

| Hemodialysis | 9 (2.7%) |

| Intubation | 146 (43.6%) |

| Ventilator days | 1 (1–2) |

| Prolonged intubation, ≥3 days | 23 (6.9%) |

| Complications ‡ | |

| Pneumonia | 48 (14.3%) |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 36 (10.7%) |

| Decubitus ulcer | 4 (1.2%) |

| Nerve palsy | 2 (0.6%) |

| Outcomes | |

| Hospital days | 2 (2–3) |

| Prolonged hospitalization, ≥5 days | 53 (15.8%) |

| Death | 3 (0.9%) |

| Complicated hospital course | 93 (27.8%) |

Data were expressed as median (interquartile range). †Standard treatment included forced diuresis, gastric lavage, activated charcoal, Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation, prolonged hospitalization, or death. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale, and laxatives. ‡Each complication was counted repeatedly.

Comparison of patients with or without a CHC

The clinical features of patients with and without a CHC were compared (Table 3). Compared with patients who did not have a CHC, those with a CHC ingested more varieties of drugs (5 [2–7] versus 3 [2–5], P < 0.01), a higher number of pills (135 [78–240] versus 84 [53–134], P < 0.0001), had a lower GCS score on admission (7 [3–11] versus 13 [8–15], P < 0.0001), higher heart rate on admission (95 [80–119] versus 85 [70–100], P < 0.001), and higher serum lactate level on admission (1.8 [1.0–3.0] versus 1.4 [0.9–2.0] mg/dL, P < 0.01) as determined by univariate analysis.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the clinical features of overdose patients with and without complicated hospital course (CHC)

| CHC (−) | CHC (+) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 242 | 93 | NA |

| Age, years | 34 (27–44) | 36 (27–44) | NS |

| Gender, male : female | 44:198 | 24:69 | NS |

| Psychiatric diseases, † yes : no | 200:18 | 83:7 | NS |

| Number of varieties (kinds) | 3 (2–5) | 5 (2–7) | <0.0100 |

| Total number of pills (tablets) | 84 (53–134) | 135 (78–240) | <0.0001 |

| Time after ingestion, ‡ h | 2.8 (2.0–5.0) | 3.5 (1.5–8.0) | NS |

| GCS score on admission | 13 (8–15) | 7 (3–11) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate on admission, b.p.m. | 85 (70–100) | 95 (80–119) | <0.0010 |

| Systolic blood pressure on admission, mmHg | 110 (100–125) | 110 (98–125) | NS |

| Oxygen saturation on admission, % | 99 (98–100) | 99 (96–100) | NS |

| Lactate on admission, mg/dL | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | 1.8 (1.0–3.0) | <0.0100 |

Data were expressed as median (interquartile range). Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation, prolonged hospitalization, or death. †n = 308, ‡ n = 233. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; NA, not applicable; NS, not significant.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with a CHC

The results of multiple logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 4. Factors included in the analysis were age, sex, total number of ingested pills, GCS score, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and serum lactate concentration on admission. Results showed that the independent risk factors for CHC were total number of ingested pills, admission GCS score, and serum lactate concentration. Sensitivity and specificity curves were examined to determine the cut‐off values that were clinically relevant for each independent risk factor (Fig. 2). The following cut‐off values were selected after examination of the curves: 100 tablets for the total number of pills ingested; score of 9 for admission GCS score; and 2.0 mg/dL for serum lactate on admission. As shown in Table 5, the odds ratios for CHC were 2–5 times greater for patients whose values exceeded the pre‐determined threshold values; these results were statistically significant.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors for complicated hospital course in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.5000 |

| Gender | 1.45 | 0.70–3.00 | 0.3200 |

| Total number of pills (tablets) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | <0.0010 |

| GCS score on admission | 0.82 | 0.76–0.88 | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate on admission, b.p.m. | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.2300 |

| Systolic blood pressure on admission, mmHg | 1.00 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.8500 |

| Oxygen saturation on admission, % | 0.90 | 0.82–1.00 | 0.0500 |

| Lactate on admission, mg/dL | 1.30 | 1.07–1.58 | <0.0100 |

Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation, prolonged hospitalization, or death. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Figure 2.

Sensitivity and specificity curves with corresponding optimal cut‐off values for the three independent factors associated with a complicated hospital course in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit of Kyorin University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan from January 2010 to December 2012 (n = 335). GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Table 5.

Odds ratios for complicated hospital course in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit calculated by multivariate analysis

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of pills ≥100 tablets | 2.80 | 1.63–4.83 | 0.0002 |

| GCS score on admission <9 | 4.75 | 2.78–8.14 | <0.0001 |

| Lactate on admission ≥2.0 mg/dL | 2.58 | 1.49–4.48 | 0.0007 |

Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation, prolonged hospitalization, or death. GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale.

Probability of CHC according to the number of risk factors

The probability of CHC for patients with 0, 1, 2, or all 3 independent risk factors were 7%, 22%, 40%, and 81%, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6.

Probability of complicated hospital course (CHC) in overdose patients admitted to the intensive care unit according to the number of independent risk factors

| No. of risk factors | No. of patients | CHC (−) | CHC (+) | Ratio of CHC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 76 | 71 | 5 | 6.6% |

| 1 | 147 | 115 | 32 | 21.8% |

| 2 | 86 | 51 | 35 | 40.7% |

| 3 | 26 | 5 | 21 | 80.7% |

Complicated hospital course was defined as the occurrence of pneumonia, rhabdomyolysis, decubitus ulcer, nerve palsy, prolonged intubation, prolonged hospitalization, or death. Three independent risk factors were: total number of pills ≥100 tablets; Glasgow Coma Scale score on admission <9; and lactate on admission ≥2.0 mg/dL.

Discussion

The present study showed that approximately a quarter (27.8%) of overdose patients admitted to ICU experienced CHC, and three‐quarters were discharged after several days without the occurrence of complications. Results also revealed that the number of ingested pills, admission GCS score, and serum lactate level on admission were predictive of CHC, with cut‐off values determined to be 100 tablets, GCS score of 9, and serum lactate of 2.0 mg/dL. Evaluation of these independent risk factors allows prediction of the risk of CHC.

Drug overdose is an increasingly frequent cause of ICU admission in Japan. An epidemiological study carried out in Japan showed that 65% of all overdose patients (considered to be less severe cases) were discharged from hospitals within 3 days, but more than 30% were brought to tertiary care hospitals for admission.1 These overdose patients sometimes cause an overflow in the ICU, so solutions are needed to address this issue.

Factors that predispose overdose patients to individual complications have been examined. Aspiration pneumonia has been associated with factors such as older age, female sex, low GCS score, delayed hospital presentation, and ingestion of opiates.4, 5 Risk factors for drug‐induced seizure include exposure to stimulants, initial hypotension, acidosis, or hyperglycemia.6

Factors associated with peripheral nerve injury include delayed hospital presentation.7 Prolonged intubation has been associated with delayed hospital presentation, low GCS score, and a sign of circulatory insufficiency.8 Also, prolonged hospitalization has been associated with male sex, older age, unintentional poisoning, disturbance of consciousness on admission, and delayed hospital presentation.9 Factors associated with ICU admission include antihypertensive medication overdose, coma on presentation, and emergency department admission less than 2 h after drug ingestion.10 To date, no consensus exists on the best method for identifying overdose patients who are at high risk of CHC.

As previously mentioned, a “50 tablets rule” exists that is widely used by paramedics in Tokyo for triaging overdose patients. The rule states that overdose patients who ingested more than 50 tablets should be triaged to tertiary care hospitals. This is based on an observational study carried out in Japan.2 This study reported that the level of consciousness prior to admission and the type of ingested drug, in addition to the number of ingested pills, should be considered in the triage of overdose patients. Although it is convenient to carry out prehospital triage of overdose patients based on the abovementioned factors, the scientific basis for this is weak. First, only the intubation rate was used to judge the appropriateness of patient triage to tertiary care facilities in the study. Second, the criteria for intubation were not clearly defined, so doctors may have arbitrarily intubated patients. Furthermore, the sensitivity and specificity of the method for predicting intubation were only 0.85 and 0.53, respectively. Thus, overtriage of patients to tertiary care hospitals may occur frequently if the reported method with a low specificity is used. The overtriage of overdose patients may contribute to patient overflow in the ICU of tertiary care hospitals. Better methods to triage high‐risk overdose patients are needed.

In our study, three independent risk factors were identified—high number of ingested pills (≥100 tablets), low admission GCS score (<9), and high serum lactate on admission (≥2.0 mg/dL)—that would be useful in the triage of overdose patients. The first two factors are useful for prehospital triage. Furthermore, the three independent factors can be used together or separately (Tables 5 and 6). If at least one risk factor is present, the sensitivity and specificity of CHC prediction are 0.95 and 0.71, respectively. Our prediction method is thus much better than the “50 tablets rule” for prehospital triage and evaluation of clinical severity.

The present study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, and the study group was relatively small. A prospective study might be needed to validate the results of the present study. Second, “CHC” is an arbitrary term that is not universally accepted. However, we believe that the use of this term is convenient and useful in clinical practice. Finally, the differential effects of each drug type were not examined. Information on the number of ingested pills is easier to obtain than the names or types of the ingested drug. In particular, paramedics can evaluate the clinical severity of patients easily using our evaluation method even if they lack knowledge of the ingested drugs.

Conclusion

The total number of ingested pills, admission GCS score, and serum lactate level on admission are predictive of CHC in overdose patients. An analysis of these factors may assist with the triage of high‐risk overdose patients to tertiary care centers and assessment of clinical severity on admission.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1. Okumura Y, Shimizu S, Ishikawa KB, Matsuda S, Fushimi K, Ito H. Characteristics, procedural differences, and costs of inpatients with drug poisoning in acute care hospitals in Japan. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2012; 34: 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hifumi T, Otomo Y, Yoshioka H, Yamaguchi J, Ishidou K, Honma M. Analysis of a prehospital triage protocol and severity assessment of patients with acute drug intoxication. J. Jpn. Soc. Emerg. Med. 2009; 12: 543–547. (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akobeng AK. Understanding diagnostic test 3: receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr. 2007; 96: 644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Isbister GK, Downes F, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. Aspiration pneumonitis in an overdose population: frequency, predictors, and outcomes. Crit. Care Med. 2004; 32: 88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christ A, Arranto CA, Schindler C et al Incidence, risk factors, and outcome of aspiration pneumonitis in ICU overdose patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006; 32: 1423–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thundiyil JG, Rowley F, Papa L, Olson KR, Kearney TE. Risk factors for complications of drug‐induced seizures. J. Med. Toxicol. 2011; 7: 16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yanagawa Y. Correlates of new onset peripheral nerve injury in comatose psychotropic drug overdose patients. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock 2011; 4: 365–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yanagawa Y, Sakamot T, Okada Y. Recovery from a psychotropic drug overdose tends to depend on the time from ingestion to arrival, the Glasgow Coma Scale, and a sign of circulatory insufficiency on arrival. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2007; 25: 757–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Satar S, Seydaoglu G. Analysis of acute adult poisoning in a 6‐year period and factors affecting the hospital stay. Adv. Ther. 2005; 22: 137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Novack V, Jotkowitz A, Delgado J et al General characteristics of hospitalized patients after deliberate self‐poisoning and risk factors for intensive care admission. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2006; 17: 485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]