Abstract

Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been associated with respiratory tract infections. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia–related pleural effusion is rarely reported. Extra-pulmonary abnormalities such as encephalitis, myocarditis, glomerulonephritis, and myringitis have been reported. However pulmonary manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus include pneumonitis, pleurisy, interstitial lung disease, and thromboembolic disease. We present the case of a 26-year-old male who came for evaluation of fever, cough, and shortness of breath with right-sided chest pain. He was found to have right-side loculated complicated parapneumonic effusion and underwent drainage with a pleural catheter followed by fibrinolytic therapy. He was then found to have new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus concomitant with Mycoplasma pneumonia, leading to lupus flare and lupus nephritis. He responded well to levofloxacin, steroids, hydroxychloroquine, and mycophenolate, with complete resolution of loculated pleural effusion and symptom improvement. Our case describes the rare combination of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia, parapneumonic pleural effusion, and lupus flare with lupus nephritis. Early identification and treatment can lead to better out come in young patients.

Keywords: Parapneumonic effusion, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Lupus flare

Abbreviations

- SLE

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- M. pneumoniae

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- MP

Mycoplasma pneumoniea pneumonia

- CT scan

computed tomography scan

- ANA

Antinuclear antibody

1. Introduction

Although Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M.pneumoniae) infections are typically mild and self-limiting, this organism is one of the most common causes of atypical pneumonia, accounting for up to 35% of cases in the United States. M. pneumoniae is transmitted from person to person by infected respiratory droplets during close contact. The incubation period after exposure averages 2to 3weeks [1]. Infections with M. pneumoniae are referred to as walking pneumonia.

Although pleural effusion is rare in cases of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia (MP), two distinct types of pleural effusion in affected patients have been reported, one of which is benign and mostly reactive, and the second of which contains Mycoplasma DNA and is a more protracted disease [2].

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystem disorder. SLE patients can experience flares ranging from mild to severe. Mild flares are associated with low-grade fever and arthralgia, where as moderate flares are associated with chest pain, swelling of the wrists, and right pleural effusion. Severe flares are associated with new-onset renal failure secondary to lupus nephritis [3].

Patients with SLE are at increase risk of developing infections. The increased frequency of infection with Mycoplasma species among patients with SLE was first suggested to be secondary to environmental factors and it is postulated that in SLE, mycoplasma peptides may provoke the production of autoreactive clones [4]. Infections of mycoplasma have been reported in SLE patients. In 1971, Jansson et al. isolated Mycoplasma from the bone marrow of 3 SLE patients [5].

2. Case presentation

A 26-year-old male with no past medical history who works as a chef at a restaurant presented to our hospital for evaluation of fever, productive cough, and shortness of breath with progressively worsening right-sided chest pain of about 5-days duration. He denied experiencing hemoptysis, hematemesis, arthralgia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. He had no exposure to birds, recent travel, or sick contacts. He also denied use of recreational drugs and alcohol and indicated that he is a non-smoker.

On physical examination, the patient was of thin build, in mild respiratory distress, febrile with a temperature of 101.5°F, heart rate 94 per minute, blood pressure of 146/84 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation of 94% on 2 liters of oxygen via a nasal cannula. On the right side of the chest, bronchial breathing sounds were noted. On cardiovascular examination, heart sounds were normal. The abdomen was soft upon palpation, with no organomegaly noted. Neurologic examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory analysis was relevant for leukocytosis (16.5 × 103 cells/μl) and mild anemia, with hemoglobin and hematocrit values of 9.7 g/dl and 29%, respectively. A creatinine level of 3.4 mg/dl was also noted. Liver function tests were within normal limits. Urinalysis showed proteinuria, considerable blood, and the test was positive for casts. Serum and urine toxicology were negative.

Chest X-ray showed bilateral pleural effusion (more pronounced on the right than left) and right lower-lobe infiltrate (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

A: Chest X-ray on day 1 showing bilateral pleural effusion. Fig 1B: Chest X-ray on day 30 showing complete resolution of pleural effusion.

Bedside ultrasound revealed loculated pleural effusion (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

: A: Ultrasound image showing loculated pleural effusion. Fig 2B: Yellow, turbid, pleural fluid.

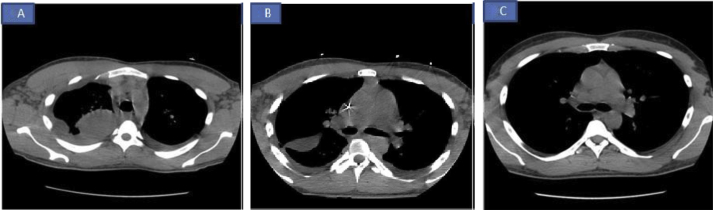

A subsequent chest computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed loculated pleural effusion (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

A: CT scan of the chest on day 1 showing loculated pleural effusion. Fig 3B: CT scan of the chest on day 7 showing improvement in loculated effusion after intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy. Fig 3C: CT scan of the chest on day 30 showing complete resolution of pleural effusion.

Bedside ultrasound-guided thoracentesis was carried out, and a pleural catheter was placed (Fig. 2B).

Pleural fluid was drained from three different loculation sites under ultrasound guidance. The results of the pleural fluid analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pleural fluid analysis.

| Color | Yellow, hazy | Yellow, cloudy | Yellow |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 |

| WBC count (cells/mm3) | 3540 | 2800 | 248 |

| Neutrophils | 95% | 96% | 70% |

| Lymphocytes | 1% | 3% | 30% |

| LDH (U/l) | 452 | 2189 | 565 |

| Protein (g/dl) | 3.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Glucose | 75 | 2 | 56 |

| Adenosine deaminase (U/l) | 18.4 |

The patient was started on antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin, and tazobactam) based on a presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia. His serum Mycoplasma IgM was 962 U/ml; cold hemagglutinin titer was 1:320; and levofloxacin was started and above antibiotics were deescalated. Analysis of pleural fluid revealed complicated parapneumonic pleural effusion. The patient then received anti-fibrinolytic therapy in the form of dornase alfa and tissue plasminogen activator for 3 days via pleural catheter. All cultures, including pleural fluid cultures, were negative. Repeat CT scan of the chest showed decreased pleural fluid and loculi (Fig. 3B).

Results of the patient's autoimmune work-up (Table 2) revealed the presence of SLE with lupus flare. The analyses revealed elevated ANA titer and homogenous speckled ANA pattern with anti-Ribonucleoprotein and anti-Smith positivity, indicative of lupus flare. The patient was therefore started on prednisone and hydroxychloroquine.

Table 2.

Results of autoimmune work-up.

| Autoimmune work-up | |

|---|---|

| Parameter | Result |

| ANA | Positive |

| ANA titer | 1:640 |

| ANA pattern | Homogenous |

| ANA pattern 2 | Speckled |

| Anti-RNP | Positive (4.3) |

| Anti-SM | Positive (6.4) |

| Anti-DNA Ab | >300 IU/ml |

| ESR | 138 |

| Serum C3 complement (mg/dl) | 78 (ref 90–500mg/dl) |

| Serum C4 complement (mg/dl) | 19 (ref 16–47mg/dl) |

| Rheumatoid factor (IU/ml) | <14 |

| SSA/SSB | <1 |

| Anti-CCP | <20 |

| C-reactive protein | 148 mg/L |

| Cardiolipin antibodies IgA, IgM, IgG | Negative |

In subsequent evaluation of renal insufficiency, the patient underwent renal biopsy, which showed lupus nephritis (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

(A) Light microscopy showing endocapillary proliferation with widespread ‘wire loop’ appearance in the glomerular capillary wall. (B)Histologic examination of tubular changes showing evidence of acute tubular necrosis and edema. (C) Light microscopy showing active crescent. (D) Immunofluorescence micrograph showing diffuse and globally distributed granular IgG deposits in the glomerular capillary walls.

He was then started on mycophenolate.

Prolonged hospital stay for almost three weeks inpatient, he was discharged home. Repeat chest X-ray (Fig. 1B).

CT scan of the chest (Fig. 3C) at the 1-month follow-up in the pulmonary clinic showed complete resolution of the loculated pleural effusion.

The patient continues to be followed in the pulmonary and rheumatology clinics.

Our case is unique, in that the patient had complicated parapneumonic effusion that responded well to anti-fibrinolytic therapy and antibiotics. He was newly diagnosed with SLE with concomitant MP leading to lupus flare with lupus nephritis.

3. Discussion

M. pneumoniae accounts to the most common causes of lower respiratory tract infections in the community setting [6]. The most common risk factors associated with M. pneumoniae include older adults, younger children, patients having immunocompromising conditions like HIV or on chemotherapy or on steroids, or smokers with lung disease [7]. Our patient did not have any of the above risk factors for development of MP.

M. pneumoniae infection can present with a variety of symptoms, including cough, sore throat, vomiting, diarrhea, ear pain, articular pain, and myalgia. Extra-pulmonary abnormalities seen in Mycoplasma infection include hemolysis, rashes, polyarthralgia, myalgia, bullous myringitis, encephalitis, meningitis, hepatitis, myocarditis and glomerulonephritis [8], [9].

Rare complications associated with M. pneumoniae infection includes acute respiratory distress syndrome, hemophagocytic syndrome, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and disseminated intravascular coagulation [10], [11]. Pleural effusion associated with MP is rare. Shuvy et al. reported a case of empyema associated with M. pneumoniae [12]. Kashif et al. reported a rare case of cavitary lesion of lung caused by Mycoplasma pneumonia [13].

SLE is a rare, multi-organ autoimmune disorder. Arthralgia is a common symptom of both lupus and Mycoplasma infection. Various Mycoplasma species have been isolated from the joint fluid and synovial membrane of SLE patients [14]. Pleural effusions in lupus are generally small, bilateral, and exudative, with elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels. Glucose levels are significantly lower in pleural fluid than in serum. Pleural fluid ANA are nonspecific, as they can also be elevated in malignancy. Pleural fluid ANA are rarely either massive or loculated. Serositis is common, and the cause of pleural effusion in SLE is usually cardiac, pulmonary embolism, or renal [15].

Pulmonary complications of SLE include pleural disease, acute pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, thromboembolic disease, shrinking lung syndrome, and increased risk of lung infections [16], [17]. The most common pulmonary manifestation of SLE is pleurisy caused by the deposition of immune complexes in the blood vessels of the lungs, with subsequent complement activation and direct binding of anti-dsDNA antibodies to the mesothelium [18]. Tissue damage in lupus is primarily via complement activation, subsequently leading to hypo-complementenemia. Class IV lupus nephritis is the most common severe form of lupus nephritis. Crescent formation, necrotizing lesions, and proliferative lesions can all be present in patients with active disease. Lesions affecting 50% or more of glomeruli have been observed under light microscopy [19].

Test results indicative of lupus flare include increased serum anti-dsDNA antibody titers, hypo-complementenemia (C3, C4, and CH50), and elevated IgG levels. Clinical features associated with lupus flare are age <25 years and renal, neurologic, and vasculitic involvement [20]. Loculated effusion is rare in MP. If pleural effusions associated with lupus are small, no treatment is required. In larger but still mild effusions, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used; with large effusions, drainage and steroid therapy might be required.

Parapneumonic effusion in Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia is one of the uncommon presentations, which occurs in 4–20% cases.

A Study done by Cha SI et al.; showed pleural fluid in Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia was exudative lymphocytic predominant in five patients and one patient had polymorphonuclear leukocyte predominance.

On the contrary, they observed elevated ADA levels in five patients, but our patient's ADA level was low, acid fast bacilli stains were negative and the neutrophilic exudate culture was negative for bacterial or viral organisms [21]. Retrospective analysis done by Linz DH et al.; showed five patients had pleural effusion which were moderate to large size, two patients had diagnostic thoracentesis which showed exudate with neutrophilic predominant effusion [22].

Retrospective study done by Kim CH et al.; showed ratio of serum LDH to pleural fluid adenosine deaminase more then 7.5 favors MP related paraneumonic effusion. Our patient serum LDH was 254 and pleural fluid adenosine deaminase level was 18, so the ratio is 14, favoring MP related parapneumonic effusion [23].

Our patient had loculated complicated parapneumonic effusion, which responded well to intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy. A study reported by Rahman et al. showed that fluid drainage is better with intrapleural t-PA-DNase therapy, resulting in decreased rates of surgical intervention and length of hospital stay [24]. The main stay of therapy for possible M. pneumoniae infection include macrolides, doxycycline, or a fluoroquinolone [25]. Our patient responded well to levofloxacin.

The goals of therapy for SLE patients are to prevent organ damage, minimize drug toxicity, and improve quality of life. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and antimalarial drugs are used to treat mild symptoms of lupus. Oral corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents can be used in severe disease. Other immunosuppressive agents that can be used include cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, and rituximab [26].

Our patient was started on Levofloxacin and underwent intrapleural fibrinolytic therapy with t-PA and dornase alfa for loculated pleural effusion. Due to renal insufficiency, a kidney biopsy was performed, which showed stage IV lupus nephritis. The patient was initially started on prednisone and hydroxychloroquine; when a renal biopsy confirmed lupus nephritis, he was started on mycophenolate, which resulted in improved renal function.

4. Conclusion

MP associated with complicated parapneumonic pleural effusion are rare. Diagnosis of lupus flare in patients with MP can prevent organ damage. Early diagnosis and timely intervention can lead to complete resolution.

Author disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement

M Khaja, R Duncalf and B Bajantri searched the literature and wrote the manuscript. M Khaja conceived and edited the manuscript. M Khaja and R Duncalf supervised the patient treatment, critically revised and edited the manuscript. S Danial and B Bajantri was involved in patient care along with M Khaja. All authors have made significant contributions to the manuscript and have reviewed it before submission. All authors have confirmed that the manuscript is not under consideration for review at any other Journal. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Bharat Bajantri, Email: bharatbajantri@gmail.com.

Shaik Danial, Email: dshaikh@bronxleb.org.

Richard Duncalf, Email: rduncalf@bronxleb.org.

Misbahuddin Khaja, Email: drkhaja@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Clyde W.A., Jr. Clinical overview of typical Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1993 Aug;17(Suppl 1):S32–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narita M., Tanaka H. Two distinct patterns of pleural effusions caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2004 Nov;23(11):1069. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000143655.11695.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isenberg D.A., Allen E., Farewell V., D'Cruz D. An assessment of disease flare in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of BILAG 2004 and the flare version of SELENA. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011 Jan;70(1):54–59. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.132068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado A.A., Zorzi A.R., Gléria A.E. Frequency of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum infections in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2001 May-Jun;34(3):243–247. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822001000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansson E., Vainio U., Tuuri S. Cultivation of a mycoplasma from the bone marrowin systemic lupus erythematosus disseminatus. Acta Rheumatol. Scand. 1971;17(3):223–226. doi: 10.3109/rhe1.1971.17.issue-1-4.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammerschlag M.R. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2001;14:181–186. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klement E., Talkington D.F., Wasserzug O., Kayouf R. Identification of risk factors for infection in an outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory tract disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006 Nov 15;43(10):1239–1245. doi: 10.1086/508458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman D., Schlaeffer F., Lieberman D., Horowitz S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae community-acquired pneumonia: a review of 101 hospitalized adult patients. Respiration. 1996;63(5):261–266. doi: 10.1159/000196557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liong T., Lee K.L., Poon Y.S., Lam S.Y. Extra pulmonary involvement associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Hong Kong Med. J. 2015 Dec;21(6):569–572. doi: 10.12809/hkmj144403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan E.D., Welsh C.H. Fulminant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. West J. Med. 1995 Feb;162(2):133–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasul S., Farhat F., Endailalu Y., Tabassum Khan F. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced-Stevens Johnson syndrome: rare occurrence in an adult patient. Case Rep. Med. 2012;2012:430490. doi: 10.1155/2012/430490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shuvy M., Rav-Acha M., Izhar U., Ron M. Massive empyema caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae in an adult: a case report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2006 Feb1;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kashif M., Dudekula R.A., Khaja M. A rare case of cavitary lesion of the lung caused by mycoplasma pneumoniae in an immunocompetent patient. Case Rep. Med. 2017;2017:9602432. doi: 10.1155/2017/9602432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartholomew L.E. Isolation and Characterization of Mycoplasma (PPLO) from patients with Rheumatoid arthritis, Systemic lupus erythematosus and Reiter's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1965 Jun;8:376–388. doi: 10.1002/art.1780080306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Light R.W. Pleural effusions. Med. Clin. North Am. 2011 Nov;95(6):1055–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamen D.L., Strange C. Pulmonary manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Chest Med. 2010 Sep;31(3):479–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincze K., Odler B., Müller V. Pulmonary manifestations in systemic lupuserythematosus. Orv. Hetil. 2016 Jul;157(29):1154–1160. doi: 10.1556/650.2016.30482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulati C.M., Satlin M.J., Magro C.M., Kirou K.A. Two systemic lupus erythematosuspatients with severe pleurisy: similar presentations, different causes. Arthritis Care Res. Hob. 2013 Jun;65(6):1005–1013. doi: 10.1002/acr.21988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiremitci S., Ensari A. Classifying lupus nephritis: an ongoing story. Sci. J. 2014;2014:580620. doi: 10.1155/2014/580620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petri M.A., van Vollenhoven R.F., Buyon J., Levy R.A., BLISS-52 and BLISS-76 Study Groups Baseline predictors of systemic lupus erythematosus flares: data from the combined placebo groups in the phase III belimumab trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Aug;65(8):2143–2153. doi: 10.1002/art.37995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha S.I., Shin K.M., Jeon K.N., Yoo S.S., Lee J., Lee S.Y., Kim C.H., Park J.Y., Jung T.H. Clinical relevance and characteristics of pleural effusion in patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2012 Oct;44(10):793–797. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.681696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linz D.H., Tolle S.W., Elliot D.L. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. Experience at are ferral center. West J. Med. 1984 Jun;140(6):895–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim C.H. Usefulness of serum lactate dehydrogenase/pleural fluid adenosine deaminase ratio for differentiating Mycoplasma pneumoniae parapneumonic effusion and tuberculous pleural effusion. J. Infect. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.08.004. (Article in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman N.M., Maskell N.A., West A., Teoh R. Intrapleural use of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase in pleural infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011 Aug 11;365(6):518–526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereyre S., Guyot C., Renaudin H., Charron A. In vitro selection and characterization of resistance to macrolides and related antibiotics in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004 Feb;48(2):460–465. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.2.460-465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertsias G., Ioannidis J.P., Boletis J., Bombardieri S., Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a task force of the EULAR standing committee for international clinical studies including therapeutics. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008 Feb;67(2):195–205. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.070367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]