Abstract

PURPOSE:

Continence is low in individuals with spina bifida, but published prevalence varies markedly across studies. The objective of this study was to examine bladder and bowel continence among patients served by multidisciplinary clinics participating in the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry and to examine whether variation in prevalence exists across clinics.

METHODS:

Data were obtained from patients 5 years and older from March 2009 to December 2012. Data were gathered at clinic visits using standardized definitions.

RESULTS:

Data from 3252 individuals were included. Only 40.8% of participants were continent of urine; 43% were continent of stool. Bladder and bowel continence differed by spina bifida type, with those with myelomeningocele having significantly lower reported prevalence of continence than those with other forms of spina bifida. Bladder and bowel continence varied across registry sites. Adjustment based on demographic and condition-specific variables did not make substantive differences in prevalence observed.

CONCLUSION:

Less than half of spina bifida patients served in multidisciplinary clinics report bladder or bowel continence. Variability in prevalence was observed across clinics. Further research is needed to examine if clinic-specific variables (e.g., types of providers, types of interventions used) account for the observed variation.

Keywords: Spina bifida, continence, neurogenic bladder, urologic management, bowel and bladder impairment, registry

1. Introduction

Spina bifida (SB), a complex and multisystem birth defect resulting from abnormal formation of the neural tube during gestation, occurs in approximately 3–6 cases per 10,000 people in the United States [1–3]. Common primary and secondary conditions include skin break down, learning and developmental delays, orthopedic problems, sensory and motor impairment, hydrocephalus, Chiari malformation, as well as bowel and bladder dysfunction [4]. Perhaps more than any other factor, bowel and bladder impairments can result in profound social stigma and decreased self-esteem [5], as well as serious health complications including renal failure and even death [6,7]. Unfortunately, neurogenic bowel and bladder are common in individuals with SB [4,8], making it difficult for them to achieve continence despite advances in medical and surgical interventions.

Extant research provides widely discrepant estimates of bowel and/or bladder continence in SB ranging from 20–87% [9–18]; a significant percentage of individuals experience “double incontinence” (i.e., both bowel and bladder) [16]. Discrepant findings in continence estimates are likely due to multiple factors. Of particular note are variations in patient phenotypes, sampling approaches, data collection methods, and definitions of continence. Further, many studies have limited their focus to participants from single clinics [19,20], which does not allow evaluating outcome variations across clinical practices.

To overcome limitations of extant data on care, health status, and outcomes for individuals with SB (including continence), starting in 2008 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began funding multidisciplinary SB clinics to implement the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry [21]. Using standardized variable definitions and processes of data collection, the NSBPR was designed to allow for a detailed description of the patient population attending SB-specific clinics and identification of processes of care that are associated with outcomes.

The purpose of this descriptive study was to measure bowel and bladder continence in patients with SB at multiple comprehensive, multidisciplinary SB clinics that are part of the NSBPR using a standardized questionnaire with a common and strict definition of continence and to determine the variation in continence prevalence across clinical programs. Describing findings from the NSBPR has the potential for contributing to a better understanding whether variations in continence previously published may be accounted for by use of different continence definitions and data collection methods across studies, or may reflect actual variations across clinic populations.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Data collection and validation

Data were obtained from March 2009 to December 2012 from 20 comprehensive SB clinics participating in the NSBPR. Detailed description of the development and implementation of the registry was described previously [21]. Briefly, to participate in the registry, clinics must be multidisciplinary, commit to collecting standardized data on specific interventions and outcomes, and have cared for a minimum of 250 patients with SB in the year prior to applying for inclusion. The clinic sites were not limited by age of patients; although all sites emphasize pediatric care, some clinics provide care to adults. At the time of collection of data used in this analysis, clinics were expected to submit data on a minimum of 125 patients annually, but were not expected to provide data on all patients.

The Institutional Review Board at participating registry sites approved procedures of the NSBPR. Participants or their legal guardians provided informed consent. Patients diagnosed with myelomeningocele, lipomyelomeningocele, meningocele, or fatty filum were invited to enroll during regularly scheduled clinic visits (legal guardians provided consent for pediatric patients). Based on chart review and/or patient interview, data were gathered at each annual visit on multiple variables considered to be valid indicators of clinical status, feasible to collect, and definable in a uniform way [22].

Designation of bladder and bowel continence status and information regarding demographic variables were determined based on the information provided by the participants and/or legal guardians at the time of registry enrollment through direct patient/care giver interview, review of medical chart, or a combination of both. Electronic and manual data quality assurance checks were performed regularly to ensure data quality [21].

2.2. Variables included in the investigation

2.2.1. Continence and bowel and bladder impairment definitions

Standardized definitions of continence were established based on a previous multi-site study examining the effectiveness of both medical and surgical interventions to promote continence [23]; these definitions were chosen because this previous work demonstrated the ability to use them to reliably gather information about continence status across multiple clinics. Bladder continence was defined as “dry, with or without interventions, during the day”. Bowel continence was defined as “no involuntary stool leakage, with or without interventions, during the day”.

Some individuals with SB do not experience neurogenic bowel and bladder. Grouping individuals with and without bowel and bladder impairment risks masking differences in outcome based on variations in disease characteristics. Thus, separating individuals based on impairment is important. The NSBPR methods do not allow for objective determination of bowel and bladder functioning/impairment. Therefore, individuals aged five years and older who were continent without intervention were classified as having “no bowel/bladder impairment” and those requiring intervention were defined as having “impairment” (e.g., patient who uses oxybutynin patch and never leaks is categorized as continent but with bladder impairment) [24].

2.2.2. Disease, demographic, and functional characteristics

Variables included in this analysis were SB diagnosis (i.e., myelomeningocele, lipomyelomeningocele, meningocele, and fatty filum), age at time of enrollment into the registry, sex, race/ethnicity (i.e., Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic or Latino), type of insurance (i.e., private, non-private), highest educational level attained, functional level of lesion based on the more severe side (i.e., thoracic, lumbar, sacral), mobility status (i.e., community ambulator, household ambulator, non-functional ambulator, non-ambulator; specific definitions available from the first author [25]), and participating clinic site (assigned unique numerical identifier).

2.3. Data analysis

Data management and analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Associations between categorical variables and bowel/bladder continence were examined in bivariate analysis by Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test as appropriate.

Multiple logistic regression models were used to analyze the associations between continence and patient demographic factors, disease characteristics, and clinic sites. Estimated odds ratios are presented with 95% confidence intervals. The clinic with the prevalence of each type of continence closest to the overall mean of all clinics was selected as the reference site, resulting in different reference clinics for bladder and bowel continence. To account for any variation in patient characteristics across the clinics, adjusted prevalence of continence (for overall and individual clinics) was obtained by predicted marginals (multivariate adjusted rates expressed as a percentage) [26] using SAS-callable SUDAAN software version 10 [27]. All analyses were first conducted including the entire sample, followed by including only those with bowel or bladder impairment.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Data from 3252 SB patients aged 5 years and older (Mean = 13.1, range 5.0–73.8 years) at the time of enrollment were included. There were 1518 males (46.4%), and 65.7% were non-Hispanic White. Regarding diagnosis, most had myelomeningocele (82.3%), lumbar level lesions (54.6%), non-private insurance (53.9%), and were community ambulators (54.4%). Of the total participants, 2894 met the definition of having “bladder impairment”, 2697 met the definition of “bowel impairment”, and 2580 met the definition for both. More detailed and additional patient characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristics (N = 3252)

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Spina bifida type | |

| Myelomeningocele | 2678 (82.3) |

| Lipomyelomeningocele | 433 (13.3) |

| Meningocele | 433 (13.3) |

| Fatty Filum | 83 (2.6) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.06) |

| Race (n = 3245) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2133 (65.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 248 (7.6) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 678 (20.9) |

| Other | 186 (5.7) |

| Function level of lesion (n = 3246) | |

| Thoracic | 591 (18.2) |

| Lumbar | 1771 (54.6) |

| Sacral | 884 (27.2) |

| Insurance (n = 3249) | |

| Any private | 1498 (46.1) |

| Non-private | 1751 (53.9) |

| Education level | |

| Pre-elementary | 298 (9.2) |

| Primary/Secondary | 2575 (79.2) |

| Technical School | 36 (1.1) |

| Some College | 182 (1.9) |

| College Degree | 61 (1.9) |

| Advanced Degree | 11 (0.3) |

| Other | 89 (2.7) |

| Mobility status | |

| Community Ambulators | 1768 (54.4) |

| Household Ambulators | 254 (7.8) |

| Non-Functional Ambulators | 213 (6.5) |

| Non-Ambulators | 1017 (31.3) |

Note. Missing data account for numbers of participants less than 3252.

3.2. Bladder continence

3.2.1. Entire sample

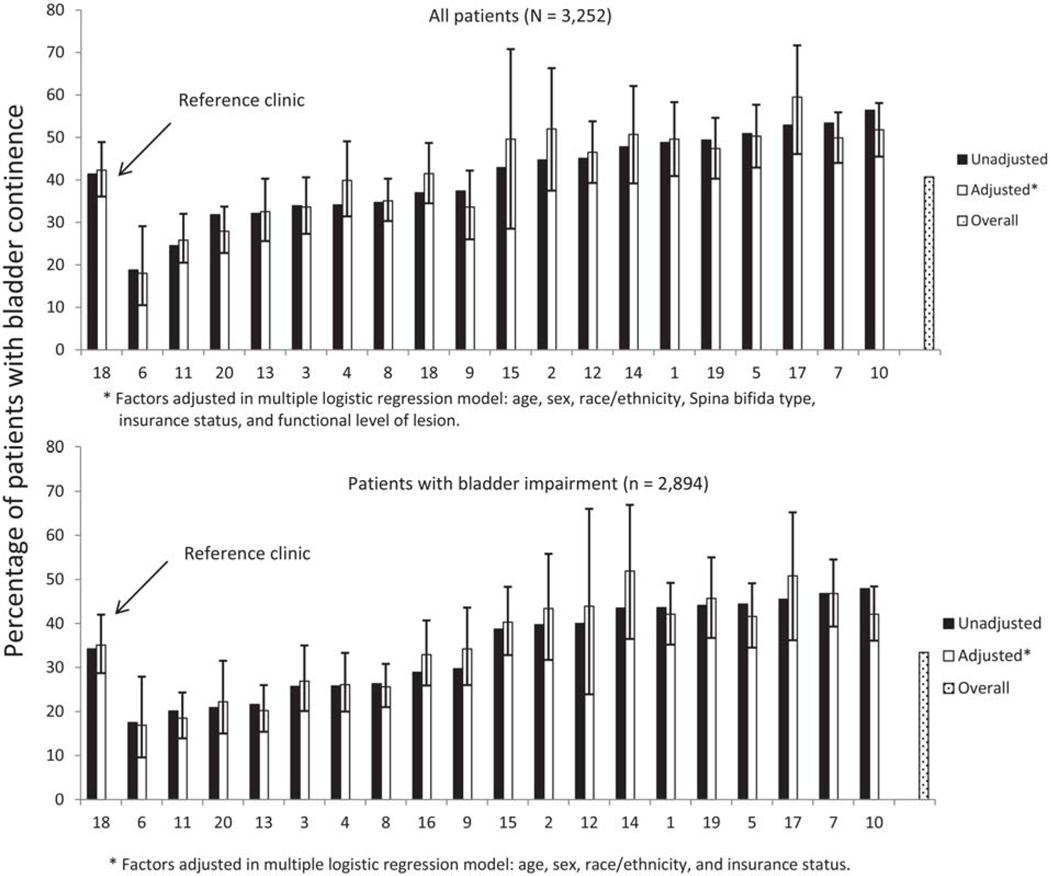

Only 1326 of the 3252 participants (40.8%) were continent of urine with or without intervention at entry into the SB Registry. A significant difference in continence status was observed between SB types (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.0001) with only 37.6% of those with myelomeningocele continent compared to over half (55.7%) of those with other forms of SB. The percentage of participants who were continent varied across clinics ranging from 18.8% to 56.4% (Fig. 1, top panel). Only four clinics reported urinary continence greater than 50%. Odds of bladder continence for the entire sample varied across clinics (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of bladder continence (unadjusted and adjusted) across registry sites.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression to examine association between patient characteristics and bladder continence (Entire Sample and With Impairment only)

| Variables | Entire Sample (N = 3236) Odds ratio (95% CI) | With Impairment (n = 2884) Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 5 to < 10 | Reference | Reference |

| 10 to < 13 | 1.23 (0.97–1.55) | 1.30 (0.99–1.71) |

| 13 to < 18 | 1.89 (1.54–2.32)* | 2.25 (1.79–2.83)* |

| 18 to < 22 | 2.33 (1.81–3.00)* | 2.88 (2.19–3.78)* |

| 22 or older | 2.04 (1.55–2.67)* | 2.44 (1.81–3.28)* |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.3 (1.17–1.57)* | 1.46 (1.24–1.72)* |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.53 (0.39–0.74)* | 0.63 (0.45–0.88)* |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0.96 (0.75–1.22) | 0.95 (0.73–1.24) |

| Other | 1.03 (0.74–1.44) | 0.79 (0.53–1.18) |

| Spina bifida type | ||

| Myelomeningocele | Reference | – – – |

| Non-Myelomeningocele | 1.69 (1.36–2.10)* | |

| Insurance | ||

| Any private | Reference | Reference |

| Non-private | 0.60 (0.51–0.71)* | 0.66 (0.55–0.79)* |

| Function level of lesion | ||

| Thoracic | Reference | – – – |

| Lumbar | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) | |

| Sacral | 1.88 (1.46–2.42)* | |

| Site | ||

| 18 | Reference | Reference |

| 6 | 1.44 (0.81–2.56) | 1.45 (0.77–2.71) |

| 11 | 0.27 (0.14–0.56)* | 0.36 (0.17–0.74)* |

| 20 | 1.37 (0.86–2.18) | 1.60 (0.98–2.62) |

| 13 | 0.50 (0.33–0.77)* | 0.40 (0.25–0.65)* |

| 3 | 1.41 (0.93–2.16) | 1.68 (1.07–2.63)* |

| 4 | 0.67 (0.44–1.02) | 0.64 (0.40–1.02) |

| 8 | 1.20 (0.79–1.81) | 1.27 (0.81–1.98) |

| 16 | 0.67 (0.41–1.09) | 0.51 (0.28–0.93)* |

| 9 | 0.96 (0.62–1.48) | 0.90 (0.56–1.45) |

| 15 | 1.25 (0.81–1.91) | 1.34 (0.85–2.11) |

| 2 | 1.51 (1.02–2.24)* | 1.37 (0.89–2.11) |

| 12 | 1.37 (0.53–3.52) | 1.48 (0.56–3.91) |

| 14 | 1.39 (0.95–2.04) | 1.37 (0.91–2.08) |

| 1 | 0.72 (0.49–1.04) | 0.62 (0.41–0.94)* |

| 19 | 0.90 (0.55–1.46) | 0.96 (0.57–1.62) |

| 5 | 0.45 (0.29–0.69)* | 0.45 (0.28–0.72)* |

| 17 | 2.21 (1.12–4.02)* | 1.99 (0.99–3.98) |

| 7 | 0.63 (0.40–1.00) | 0.67 (0.40–1.10) |

| 10 | 1.52 (0.76–3.08) | 2.09 (1.01–4.32)* |

Note. Asterisk signifies confidence intervals that do not include 1.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, SB type, insurance type, functional level of lesion, and clinic site were associated with bladder continence independently (see Table 2). After controlling for these variables, the adjusted percentage of patients with bladder continence among the 20 clinics ranged from 18% to 59.5% (Fig. 1, top panel); adjustment did not make a substantive difference in this variation or in odds ratios (Table 2).

3.2.2. Those with bladder impairment

Of those who met our criteria for bladder impairment (n = 2894), only 968 participants (33.4%) were continent of urine with or without intervention. Unlike with the entire sample, no significant difference in prevalence of bladder continence was observed between those with myelomeningocele and those with other forms of SB (33.9% and 30.4%, respectively; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.192). Percentage of participants who were continent continued to vary significantly across clinics ranging from 17.5% to 47.9% (Fig. 1, bottom panel). No clinics reported a prevalence of urinary continence greater than 50% of those with bladder impairment; seven clinics reported a prevalence of urinary continence greater than 40% among enrollees with impairment. Odds of bladder continence also varied across clinics for those with bladder impairment (Table 2).

When considering only those with bladder impairment, only age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance type, and clinic site were associated with bladder continence independently (Table 2). After controlling for these variables, the adjusted percentage of patients with bladder continence among the clinics ranged from 16.9% to 50.8% (Fig. 1, bottom panel); adjustment did not make a substantive difference in this variation or in odds ratios (Table 2).

3.3. Bowel continence

3.3.1. Entire sample

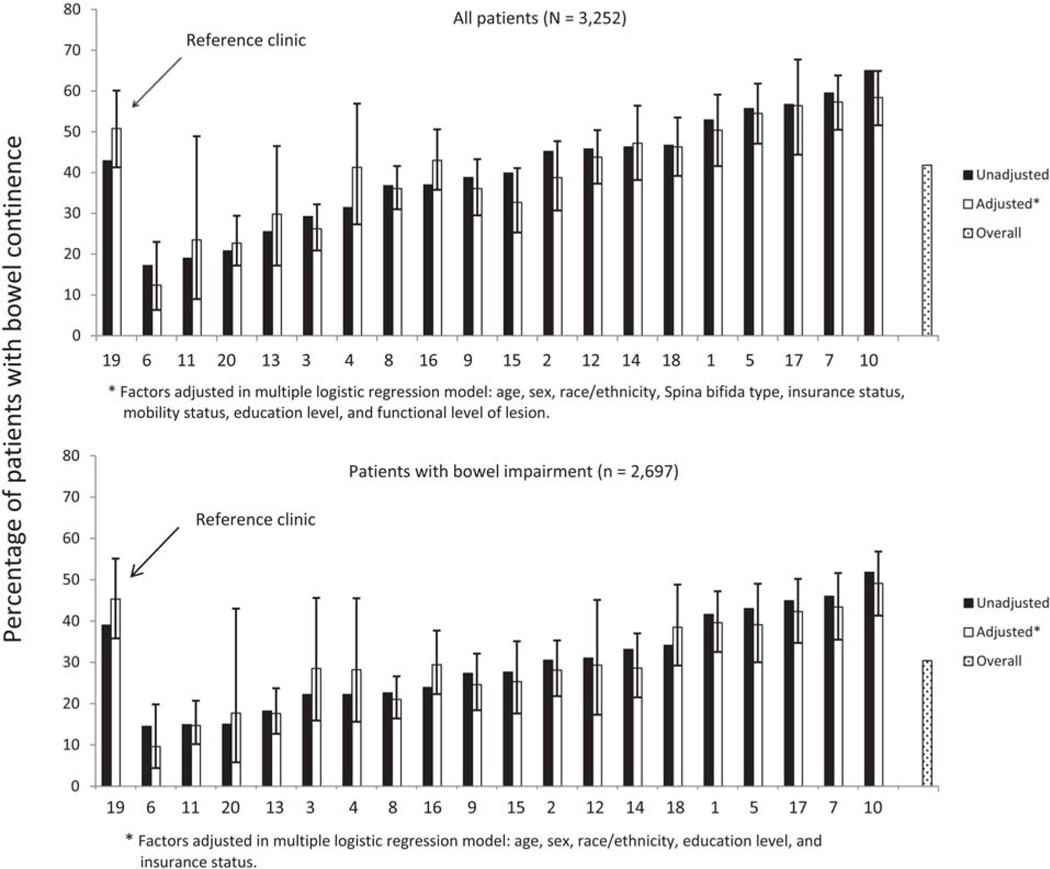

A total of 1398 (43.0%) of the 3252 participants were continent of stool at entry into the registry. Again, continence status varied significantly by SB type; only 39.6% of those with myelomeningocele were continent, compared to 58.9% of those with non-myelomeningocele SB (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.0001). The percentage of participants who were continent of stool varied significantly across clinics ranging from 17.2% to 65.0% (Fig. 2, top panel). Five clinics reported prevalence of stool continence greater than 50%. Odds of bowel continence for the entire sample varied across clinics (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of bowel continence (unadjusted and adjusted) across registry sites.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression to examine association between patient characteristics and bowel continence (Entire Sample and With Impairment only)

| Variables | Entire Sample (N = 2859) Odds ratio (95% CI) | With Impairment (n = 2396) Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 5 to < 10 | Reference | Reference |

| 10 to < 13 | 1.23 (0.96–1.59) | 1.29 (0.96–1.73) |

| 13 to < 18 | 1.84 (1.46–2.32)* | 1.70 (1.31–2.21)* |

| 18 to < 22 | 2.15 (1.56–2.95)* | 1.95 (1.37–2.78)* |

| 22 or older | 1.66 (1.18–2.34)* | 1.25 (0.84–1.84) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.25 (1.06–1.47)* | 1.32 (1.10–1.60)* |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.51 (0.37–0.71)* | 0.52 (0.36–0.76)* |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0.91 (0.70–1.17) | 0.91 (0.68–1.23) |

| Other | 0.85 (0.60–1.21) | 0.70 (0.45–1.09) |

| Spina bifida type | ||

| Myelomeningocele | Reference | – – – |

| Non-Myelomeningocele | 1.76 (1.39–2.23)* | |

| Insurance | ||

| Any private | Reference (n = 1498) | Reference |

| Non-private | 0.53 (0.45–0.64)* | 0.52 (0.43–0.64)* |

| Function level of lesion | ||

| Thoracic | Reference | – – – |

| Lumbar | 1.11 (0.84–1.48) | |

| Sacral | 1.60 (1.12–2.29)* | |

| Mobility status | ||

| Community | Reference | – – – |

| Household | 1.12 (0.81–1.54) | |

| Non-Functional | 0.75 (0.53–1.08) | |

| Non-Ambulators | 0.76 (0.58–0.99)* | |

| Education level | ||

| Pre-elementary | Reference | – – – |

| Primary/Secondary | 1.54 (1.12–2.11)* | |

| Site | ||

| 19 | Reference | Reference |

| 6 | 1.28 (0.66–2.48) | 0.48 (0.21–1.10) |

| 11 | 0.12 (0.05–0.28)* | 0.12 (0.04–0.30)* |

| 20 | 0.98 (0.56–1.72) | 0.76 (0.42–1.39) |

| 13 | 0.31 (0.18–0.53)* | 0.19 (0.10–0.35)* |

| 3 | 1.18 (0.70–1.99) | 0.92 (0.53–1.60) |

| 4 | 0.52 (0.30–0.88)* | 0.37 (0.21–0.67)* |

| 8 | 0.82 (0.49–1.37) | 0.78 (0.46–1.33) |

| 16 | 0.59 (0.33–1.04) | 0.39 (0.20–0.75)* |

| 9 | 0.71 (0.42–1.22) | 0.48 (0.26–0.88)* |

| 15 | 0.44 (0.25–0.77)* | 0.46 (0.26–0.83)* |

| 2 | 1.40 (0.84–2.34) | 1.18 (0.68–2.02) |

| 12 | 0.27 (0.08–0.88)* | 0.24 (0.06–0.90)* |

| 14 | 1.33 (0.81–2.21) | 0.88 (0.51–1.51) |

| 18 | 0.73 (0.44–1.22) | 0.45 (0.26–0.78)* |

| 1 | 0.52 (0.32–0.83)* | 0.30 (0.18–0.51)* |

| 5 | 0.25 (0.15–0.44)* | 0.24 (0.13–0.43)* |

| 17 | 0.66 (0.31–1.41) | 0.46 (0.20–1.08) |

| 7 | 0.85 (0.49–1.48) | 0.74 (0.41–1.35) |

| 10 | 0.38 (0.16–0.90)* | 0.45 (0.18–1.11) |

Note. Asterisk signifies confidence intervals that do not include 1.

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, SB type, functional level of lesion, insurance type, education level, mobility status, and clinic site were associated with bowel continence independently (see Table 3). After controlling for these variables, the adjusted percentage of bowel continence among the 10 clinics ranged from 12.4% to 58.4% (Fig. 2, top panel); adjustment did not make a substantive difference in this variation or in odds ratios (Table 3).

3.3.2. Those with bowel impairment

Of those who met the definition for bowel impairment (n = 2697), only 843 (31.3%) were continent of stool with our without intervention at entry into the registry. Prevalence of bowel continence did not vary significantly by condition type (myelomeningocele 31.1%, other SB types 32.6%; Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.578). The percentage of participants who were continent of stool continued to vary significantly across clinics (Fig. 2, bottom panel). Only one clinic reported a prevalence of stool continence greater than 50% for participants with bowel impairment. Odds of bowel continence for those with impairment varied across clinics (Table 3).

Age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance type, and clinic site were associated with bowel continence independently for those with bowel impairment (Table 3). After controlling for these variables, the adjusted percentage of bowel continence among the 20 clinics ranged from 9.5% to 49.1% (Fig. 2, bottom panel); adjustment did not make a substantive difference in this variation or in odds ratios (Table 3).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this multi-center study is the largest to investigate the prevalence of urinary and bowel continence in individuals with SB, and the first to examine variation across clinics in these variables. Using uniform definitions of “dry. . . during the day” and “no involuntary stool leakage. . . during the day,” only 40.8% and 43.0% of the entire cohort of 3252 individuals aged 5 years and older were reported as continent of urine and stool, respectively. These figures were lower when only those with myelomeningocele (37.6% and 39.6%) and those with bladder/bowel impairment (33.4% and 31.3%) were analyzed. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, SB type, functional level of lesion, insurance type, mobility status (bowel continence only), and education status (bowel continence only) were significantly and independently associated with continence.

These findings are sobering to those who care for patients with SB. All individuals included in this study received care at specialized, multi-disciplinary SB clinics and should have had access to the best and latest medical and surgical interventions to gain both urinary and bowel continence. Despite this, less than half of the entire cohort reported continence, and approximately one-third of those with known bladder and bowel impairment were continent. This is occurring in an era in which SB care has advanced beyond survival and has been focusing on quality of life improvement [5,28,29]. While it is currently unclear whether continence for 100% of patients will ever be achieved, these data serve as a continued charge to professionals caring for individuals with SB to strive toward identifying and implementing interventions that result in the best possible continence status for each individual patient.

Variation between clinic sites in the NSBPR was considerable, with prevalence of continence ranging 16.9–50.8% for urine and 9.5–49.1% for stool, even after controlling for demographic and condition-specific patient variables recorded as part of the registry. Clearly, our findings showed that less severe types of SB had better continence, but lesion level and mobility do not reliably predict bladder and bowel impairment [30]. Restriction of analysis to only those with bladder and bowel impairment still showed wide variation in continence rates, so selection bias based upon neurologic differences between different clinic populations may not explain continence variation across clinics. While socio-economic and demographic factors were independently associated with continence, clinic site variation in continence persisted when controlling for these factors. It is possible that other patient characteristics not tracked in the NSBPR may explain some of this variation, or that the analytic approach did not allow for detection of some associations because they are nonlinear. Socio-economic factors were not fully characterized, and parental/familial education levels and compliance with therapies were not assessed and could account for some site-specific differences. Whether inclusion of different patient, intervention, adherence, or clinic variables in analyses would eliminate variation by site is an important area of future research.

Observed variation in continence across clinics may contribute to an understanding of why previous research has documented such wide variability across studies. That is, sampling procedures in previous studies estimating continence rates have varied significantly (e.g., single or small number of clinics, community survey sampling). Our findings raise the possibility that recruitment from single or a small number of clinics may result in findings that are more reflective of local variables affecting continence rather than condition-based variables that are generalizable across the population of individuals with SB. Additional research is needed to further explore this possibility.

Bladder and bowel continence rates may be lower in this study than in previous research due to the stricter definition of continence. There is great variability in definitions of continence in the literature [15], ranging from one or more soiling or wetting accident per month [13,31], to complete absence of urinary leakage or fecal accidents [19]. Some studies have failed to provide a definition of continence [15,16], whereas others have emphasized distinctions between continence and being socially dry [11]. The definitions used in our study does not make allowance for small volume or infrequent incontinence that may be caused by occasional imperfect compliance with bladder and bowel regimens or extenuating circumstances and may not truly reflect the successes of clinic sites or specific behavioral, medical, or surgical interventions based on other definitions of continence (e.g., social continence). This is being addressed in future studies by quantifying and qualifying incontinence in more nuanced ways in version 2 of the NSBPR questionnaire, which was instituted after these data were collected. Additionally, continence rates in our study may not be reflective of the entire SB population as those with no or minimal problems may not attend specialized SB clinics.

Variability in continence across clinic sites may be partially attributable to data collection methods. Although the registry had a single definition of continence for bladder and for bowel, the method in which the questions were asked was not standardized. Ideally, information was taken from the medical records, but may have been gathered via face-to-face interview or by the individual completing a standardized questionnaire. How questions are asked and by whom may affect responses [32]. The existing SB literature is illustrative of this potential variability in continence rates with utilization of retrospective chart review [19], patient interview [13,31], and questionnaire-based assessment methods [12]. On the other hand, variability in continence between clinic sites could be related to practice differences in medical and surgical interventions – in how frequently they are utilized, the types utilized, and the skill in which they are performed/implemented. Attempts to explain variability in continence rates by examining variations in interventions across clinics were not conducted for the current study, but are being examined.

Another important potential explanation of the variation in continence across clinics is possible selection or enrollment bias. Specifically, at the time of collection of data included in the current analysis, participating clinics were required to submit data on a minimum number of patients annually, but were not required to enroll all eligible participants. Whether differences in those enrolled versus those who were eligible but not enrolled accounts for variations in continence observed cannot be ruled out. Procedural updates to the NSBPR starting in 2014 require participating sites to provide basic demographic and condition-specific information on non-enrolled individuals without the inclusion protected health information, which may allow for control of any possible selection in future analyses.

Finally, errors in data acquisition and entry cannot be eliminated in a large study encompassing 20 sites. However, the NSBPR involves rigorous data quality checks and assurance procedures to maximize data accuracy [21].

5. Conclusion

These findings are instructive for all who care for individuals with SB in that urinary and bowel continence rates are relatively poor. These rates appear to vary significantly between leading SB clinics in the US and may reflect practice differences. Goals of the NSBPR included the identification of variations in care and development of best practices [21]; it is hoped that these efforts can be incorporated into bladder and bowel management of all SB individuals to improve care and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The development of the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry has been successful due to the contributions of all the members of the NSBPR Coordinating Committee. Members of this committee during the collection of the data reported here were William Walker, Seattle Children’s Hospital; Kathryn Smith, Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles; Kurt Freeman, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland; Pamela Wilson, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora; Kathleen Sawin, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin and Froedtert Hospital, Milwaukee (adult clinic); Jeffrey Thomson, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, and Shriners Hospital for Children, Springfield; Heidi Castillo, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati; David Joseph, Children’s Hospital of Alabama and University of Alabama at Birmingham; Jacob Neufeld, St. Luke’s Boise Medical Center, Boise; Robin Bowman, Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Chicago; Karen Ratliff-Schaub, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus; Jim Chinarian, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit; John Wiener, Duke University Medical Center, Durham; Mark Dias, Hershey Medical Center, Hershey; Tim Brei, Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis; Brad Dicianno, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, (adult clinic) Pittsburgh; Paula Peterson, Primary Children’s Medical Center, Salt Lake City; Elaine Pico, UCSF, San Francisco, and Children’s Hospital and Research Center, Oakland.

The National Spina Bifida Patient Registry is funded by the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants #1UO1DDD000 742.01; 1UO1DDD000766.01; 1UO1DDD000772.01. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Copyright of Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine is the property of IOS Press and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

References

- [1].Canfield MA, Honein MA, Yuskiv N, Xing J, Mai CT, et al. National estimates and race/ethnic-specific variation of selected birth defects in the United States, 1999–2001. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2006; 76: 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Larson S, Lakin C, Anderson L, Kwak N, Hak Lee J, Anderson D. Prevalence of mental retardation and/or developmental disabilities: Analsysis of the 1994/1995 NHIS-D. 2000: Institute; on Community Integration. Minneapolis: Research And Traning Center On Community Living. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shin M, Besser LM, Siffel C, Kucick JE, Shaw GM, Lu C, Correa A. Prevalence of spina bifida among children and adolescents in 10 regions of the United States. Pediatrics, 2010; 126: 274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sandler AD. Children with spina bifida: Key clinical issues. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2010; 57: 879–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sawin KJ, Bellin MH. Quality of life in individuals with spina bifida: A Research update. Developmental Disabilities Research Review. 2010; 16: 47–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].McDonnell GV, McCann JP. Why do adults with spina bifida and hydrocephalus die? A clinic based study. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2000; 10(suppl): 31–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Singhal B, Mathews KM. Factors affecting mortality and morbidity in adult spina bifida. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1999; 1(suppl 9): 31–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Anderson PA, Travers AH. Development of hydronephrosis in spina bifida patients: Predictive factors and management. British Journal of Urology. 1993; 72: 958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hagelsteen JH, Lagergren J, Lie HR, Rasmussen F, Borjenson MC, et al. Disability in children with myelomeningocele. A Nordic study. Acta Paediatrica Sandinavica. 1989; 78: 721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].King JC, Currie DM, Wright E. Bowel training in spina bifida: Importance of education, patient compliance, age, and anal reflexes. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 1994; 75: 243–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Knoll M, Madersbacher H. The chances of a spina bifida patient becoming continent/socially dry by conservative therapy. Paraplegia. 1993; 31: 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Krogh K, Lie HR, Bilenberg N, Laurberg S. Bowel function in Danish children with myelomeningocele. APMIS. Supplementum. 2003; 109: 81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lemelle JL, Guillemin F, Aubert D, Guys JM, Lottmann H, et al. A multicenter evaluation of urinary incontinence management and outcome in spina bifida. Journal of Urology. 2006; 175: 208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lie HR, Lagergren J, Rasmussen F, Lagerkvist B, Hagelsteen J, et al. Bowel and bladder control of children with myelomeningocele: A Nordic study. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1991; 33: 1053–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lloyd JC, Nseyo U, Madden-Fuentes RJ, Ross SS, Wiener JS, et al. Reviewing definitions of urinary continence in the contemporary spina bifida literature: A call for clarity. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2013; 9: 567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Malone PS, Wheeler RA, Williams JE. Continence in patients with spina bifida: Long term results. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1994; 70: 107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mevorarch RA, Bogaert GA, Baskin LS, Lazzaretti CC, Edwards MS, et al. Lower urinary tract function in ambulatory children with spina bifida. British Journal of Urology. 1996; 77: 593–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wright L The efficacy of bowel management in the adult with spina bifida. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2002; 12(Suppl 1): 41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Metcalf P, Gray D, Kiddoo D. Management of the urinary tract in spina bifida cases varies with lesion level and shunt presence. Journal of Urology. 2011; 185: 2547–2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vande Velde S, Van Biervliet S, Van Renterghen K, Van Laecke E, Hoebeke P, et al. Achieving fecal continence in patients with spina bifida: A descriptive cohort study. Journal of Urology. 2007; 178: 2540–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thibadeau J, Ward E, Soe MM, Liu T, Swanson M, et al. Testing the feasibility of the of a National Spina Bifida Patient Registry. Birth Defects Research (Part A). 2013; 97: 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schechter MS. Patient registry analyses: Seize the data, but caveat lector. Journal of Pedatrics. 2008; 153: 733–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Smith K, Neville-Jan A, Freeman KA, Adams E, Mizokawa S, Dudgeon BJ, Merkens MJ, Walker WO. The effectiveness of bowel and bladder interventions in children with spina bifida. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2016; 58: 979–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sawin KJ, Liu T, Ward E, Thibadeau J, Schechter MS, et al. The National Spina Bifida Patient Registry: Profile of a large cohort of participants from the first 10 clinics. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2014; 166: 444–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Joffer MM, Feiwell E, Perry R, Perr J, Bonnett C. Functional ambulation in patients with myelomeningocele. Journal of Bone & Joint Survery: American Edition. 1973; 55: 137–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999; 55: 652–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 100. First Edition. 2008. Research; Triangle Park: Author. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bowman RM, McLone DG, Grant JA, Tomita T, Ito JA. Spina bifida outcome: A 25-year prospective. Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2001; 34(3): 114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dicianno BE, Kurowski BG, Yang JM, Canceloor MB, Bejjani GK, et al. , Rehabilitation and medical management of the adult with spina bifida. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2008; 87: 1026–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].MacLellan DL, Bauer SB. Neuromuscular dysfunction of the lower urinary tract in children. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA(Eds.), Campbell-Walsh Urology. 2016. (11 ed., pp. 1761–1795). Philadelphia: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Verhoef M, Lurvink M, Barf HA, Post MW, van Askbeck FW, et al. High prevalence of incontinence among young adults with spina bifida: Description, prediction, and problem perception. Spinal Cord. 2005; 43: 331–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Holm HV, Fosså SD, Hedlund H, Schultz A, Dahl AA. How should continence and incontinence after radical prostatectomy be evaluated? A prospective study of patient ratings and change over time. Journal of Urology. 2014; 192: 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]