Abstract

Introduction

In the U.S., approximately 73% of homeless adults smoke cigarettes and they experience difficulty quitting. Homeless smokers report low self-efficacy to quit and that smoking urges are a barrier to quitting. Self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges are dynamic and change throughout smoking cessation treatment. This study examines changes in self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges throughout a smoking cessation intervention among the homeless and identifies predictors of change in these characteristics.

Methods

Homeless smokers (n=430) participating in a smoking cessation randomized controlled trial in the U.S. completed surveys at baseline, and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 26 on demographic and smoking characteristics (i.e., confidence to quit, self-efficacy to refrain from smoking, and smoking urges). A growth curve analysis was conducted by modeling change in the smoking characteristics over time and examining the variability in the change in smoking characteristics by demographic characteristics and treatment group.

Results

Among the full sample, self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly over time, confidence to quit increased until the midpoint of treatment but subsequently decreased, and smoking urges decreased until the midpoint of treatment but subsequently increased. There were race differences in these trajectories. Racial minorities experienced significantly greater increases in self-efficacy to refrain from smoking than Whites and Blacks had higher confidence to quit than Whites.

Conclusions

White participants experienced less increase in self-efficacy to refrain from smoking and lower confidence to quit and therefore may be a good target for efforts to increase self-efficacy to quit as part of homeless-targeted smoking cessation interventions. Sustaining high confidence to quit and low smoking urges throughout treatment could be key to promoting higher cessation rates among the homeless.

Keywords: smoking cessation, self-efficacy to quit, smoking urges, growth curve modeling, race/ethnicity

1. Introduction

Three million people experience homelessness in the United States each year and over 578,400 are homeless each night (1,2). The mortality rate among the homeless is higher than among the general population, with cancer being one of the leading causes of death (3–5). Many of these cancer-related deaths could be prevented through lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation (6). Promotion of smoking cessation is especially important among the homeless since lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths; 73% of homeless adults smoke cigarettes, a rate over three times the national rate; and homeless individuals experience difficulty quitting and maintaining abstinence (5, 7–10). The health consequences of smoking may be especially high among the homeless due to higher incidence of chronic disease and prevalence of substance abuse, which can synergistically with tobacco use increase the risk of cancer (11–13).

To promote smoking cessation among the homeless, it is important to understand factors related to successful smoking cessation. According to the Self-Efficacy Theory, for change in behavior, such as smoking cessation to occur, an individual must feel convinced that the change will improve his/her well being and confident that he/she can make the change (14). Without confidence or self-efficacy, an individual will lack the energy to sustain the change process. In line with this theory, it has been demonstrated that high self-efficacy to quit facilitates smoking cessation, (15–17) and individuals with higher self-efficacy to quit are more likely to quit permanently than individuals with lower self-efficacy to quit (16). Homeless smokers report lower self-efficacy to quit compared to domiciled socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers (18). Smoking urges are also related to smoking status. Smoking urges are a principal cause of addictive smoking and relapse, (19,20) and a barrier to smoking cessation (21). Among homeless smokers, smoking urges are an important barrier to cessation (22).

Self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges are dynamic and can change over the course of treatment (23,24). Therefore, examining self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges using data from a single time point is likely inadequate for determining levels of these characteristics. Previous studies examining changes in self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges over time found most individual’s self-efficacy to quit decreases from post-treatment to follow-up (25). However, individuals with high self-efficacy to quit at baseline tend to have high self-efficacy to quit from post-treatment to follow-up (25). Individuals with higher self-efficacy to quit are more likely to try to quit, and individuals who maintain their level of self-efficacy to quit over the course of a quit attempt are more likely to achieve long term abstinence (26,27). There is a strong negative association over time between smoking urges and self-efficacy to quit, (24) with decreasing self-efficacy to quit during a quit attempt followed by increased smoking urges (28,29). A complementary explanation is strong smoking urges may undermine self-efficacy to quit (24,30).

Although there have been previous studies examining changes in self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges over time, none of the studies included the homeless population, who experience difficulty quitting (8–10). Examining patterns in self-efficacy to quit and smoking urges among the homeless may help inform efforts to maintain high levels of self-efficacy to quit and low levels of smoking urges throughout treatment in order to promote higher rates of smoking cessation.

In addition, none of the studies to date have examined demographic differences in self-efficacy to quit longitudinally and only a few studies have examined demographic differences in smoking urges longitudinally. There is cross-sectional evidence to suggest self-efficacy to quit differs by demographic characteristics. Higher levels of self-efficacy to quit have been observed among racial minorities, older individuals, and men (26, 31–38). Two longitudinal studies found higher levels of smoking urges among racial minorities and decreased smoking urges among younger individuals (39,40). Other studies found differences in patterns of craving in experimental settings by gender, but self-reported smoking urges haven’t been examined by gender (41,42). Identifying groups of homeless individuals who have lower self-efficacy to quit and higher smoking urges over the course of treatment would allow tailoring of smoking cessation efforts to homeless individuals who are the least likely to quit smoking.

This study examines changes in smoking characteristics among homeless individuals in the Twin Cities, MN. The aims of this study are to 1) examine change in smoking characteristics (i.e., smoking urges and two measures of self-efficacy to quit, self-efficacy to refrain from smoking and confidence to quit) over the course of a smoking cessation randomized controlled trial, and 2) determine whether treatment group, age, gender, and race are predictors of change in the smoking characteristics among homeless smokers.

Although confidence to quit and self-efficacy to refrain from smoking are both measures of self-efficacy to quit, they measure different components of self-efficacy to quit. The former measures general self-efficacy to quit completely and the latter measures self-efficacy to not smoke in particular situations without asking about complete cessation. Self-efficacy has a multidimensional structure: general self-efficacy can be high yet self-efficacy can be low in specific situations (43). Therefore, we examine both in this study.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Study Design

Study data were derived from the Power to Quit study, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 430 homeless adult smokers that assessed the effectiveness of motivational interviewing (MI) for smoking cessation (9,44). The design and main outcomes of the parent study were previously described (9,44). Participants were recruited from 8 homeless emergency shelters and transitional housing sites in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota from May 2009 to August 2010. Eligibility criteria included being currently homeless and having lived in the Twin Cities for at least six months, having smoked at least one cigarette per day in the past seven days and at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, aged 18 years or older, and willing to use nicotine patches for eight weeks and participate in counseling sessions. Exclus ion criteria included pregnancy, use of another tobacco cessation aid in the previous 30 days, severe cognitive impairment, suicidal ideation in the last 14 days, a major medical condition within the prior month, or scoring greater than five on items assessing psychotic symptoms from the seven-item Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (45).

At baseline participants were randomized to an intervention arm, nicotine patch plus MI, or a control arm, nicotine patch plus standard care (SC). Intervention participants received six individual MI counseling sessions each lasting 15–20 minutes, which focused on encouraging smoking cessation and nicotine replacement therapy adherence. Control participants received a one-time advice session on quitting smoking lasting 10–15 minutes. Participants in both conditions received 21mg nicotine patches for eight weeks. Surveys were administered at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 (end of treatment), and 26 (follow-up). This study was approved and monitored by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2 Measures

Smoking Characteristics

Intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking were measured on the baseline, week 8, and week 26 surveys using the Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (SEQ-12) (46). Participants were asked to indicate how sure they are that they could refrain from smoking in 6 intrinsic (e.g., when I feel depressed) and 6 extrinsic (e.g., when having drinks with friends) situations on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all sure) to 5 (absolutely sure). The intrinsic and extrinsic items were summed to create two scales ranging from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. The Cronbach’s alpha for the intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking items was 0.87 at baseline, 0.88 at week 8, and 0.89 at week 26, indicating good reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha for the extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking items was 0.88 at baseline, 0.87 at week 8, and 0.89 at week 26, indicating good reliability.

Confidence to quit was measured on all of the surveys (i.e., baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 26) by asking participants to report how confident they are that they could quit smoking completely or stay quit if they wanted to on a scale of 0 (not confident) to 10 (extremely confident). Smoking urges was measured on all of the surveys using the Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-Brief) (47). Participants were asked to indicate the extent they agreed or disagreed with 10 statements about their smoking urges (e.g., I have a desire for a cigarette right now; I would do almost anything for a cigarette right now). Answer options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). All 10 items were summed to create a scale ranging from 10 to 70, with higher scores indicating greater smoking urges. The Cronbach’s alpha for these items at each time point ranged from 0.92 to 0.96, indicating excellent reliability.

Demographic Characteristics

On the baseline survey, participants reported their date of birth, sex (i.e., male, female, or other (specify)), and race/ethnicity (Black, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Native American/Alaskan Native, and/or White). Age was calculated using date of birth. Race was collapsed into White, Black, or other.

2.3 Analysis

This study includes data from baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 26 from participants in the Power to Quit study. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 13. Descriptive statistics were examined for the smoking characteristics at each time point and age, gender, and race at baseline.

A growth curve analysis was conducted (STATA General Linear Mixed Model). In the first phase of the analysis, we modeled the change in smoking characteristics over time. We estimated a series of unconditional models using general linear mixed models with unstructured covariance patterns. Intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking were measured at three time points (baseline, week 8, and week 26); therefore, we estimated models for lines with no change and linear trajectory. Confidence to quit and smoking urges were measured at over five time points (baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 26); therefore, we estimated models for lines with no change, linear trajectory, curving monotonic trajectory, and curving nonmonotonic trajectory. For each smoking characteristic, we compared the estimated models by examining model fit criteria (i.e., AIC and −2LL) and the significance of model parameters to select the best fitting model. We plotted the average growth curve using the best fitting model for each smoking characteristic.

In the second phase of the growth curve analysis, we examined the variability in change in smoking characteristics over time by regressing the intercept and slope(s) from the best fitting general linear mixed models on treatment group, age, gender, and race. All predictors were required to be categorical to be entered into the model; therefore, age was dichotomized using a median split. We plotted the average growth curve for each smoking characteristic by the statistically significant predictors.

3. Results

Participants in the Power to Quit study (n=430) were an average of 44 years of age (mean=44.4, SD=9.9) and 74% were male (n=320). Fifty-six percent of participants were Black (n=243), 36% were White (n=153), and 8% were of another race or mixed race (n=34). As previously reported, there were no significant differences in demographic characteristics by treatment group (9). Table 1 outlines the smoking characteristics of homeless smokers over the course of the study. Intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking was on average 16.9 (scale 6–30) at baseline and 20.2 at 26-weeks follow-up. Extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking was on average 16.8 (scale 6–30) at baseline and 19.6 at 26-weeks follow-up. Confidence to quit was on average 7.3 (scale 0–10) at baseline and 7.7 at 26-weeks follow-up. Smoking urges was on average 39.8 (scale 10–70) at baseline and 19.7 at 26-weeks follow-up. Only 7% of smokers (n=32) quit at 26-weeks follow-up. Twenty-five percent of data were missing at weeks 6, 8, and 26.

Table 1.

Smoking Characteristics of Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

| Variable | Baseline N |

Baseline Mean (SD) |

Week 1 N |

Week 1 Mean (SD) |

Week 2 N |

Week 2 Mean (SD) |

Week 4 N |

Week 4 Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Self-efficacy to refrain from smoking | ||||||||

| Intrinsic, scale 6–30 | 429 | 16.9 (6.8) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Extrinsic, scale 6–30 | 426 | 16.8 (7.8) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

|

| ||||||||

| Confidence to quit, scale 0–10 | 430 | 7.3 (2.4) | 379 | 8.0 (2.1) | 358 | 8.3 (1.8) | 356 | 8.2 (2.0) |

|

| ||||||||

| Smoking urges, scale 10–70 | 430 | 39.8 (17.7) | 374 | 23.2 (13.5) | 357 | 21.6 (13.5) | 354 | 20.4 (13.5) |

| Variable | Week 6 N |

Week 6 Mean (SD) |

Week 8 N |

Week 8 Mean (SD) |

Week 26 N |

Week 26 Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Self-efficacy to refrain from smoking | ||||||

| Intrinsic, scale 6–30 | − | − | 322 | 21.5 (6.5) | 324 | 20.2 (6.9) |

| Extrinsic, scale 6–30 | − | − | 327 | 21.1 (7.1) | 323 | 19.6 (7.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Confidence to quit, scale 0–10 | 328 | 8.2 (1.9) | 327 | 8.4 (2.0) | 323 | 7.7 (2.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Smoking urges, scale 10–70 | 328 | 19.9 (13.1) | 326 | 18.4 (12.1) | 322 | 19.7 (13.4) |

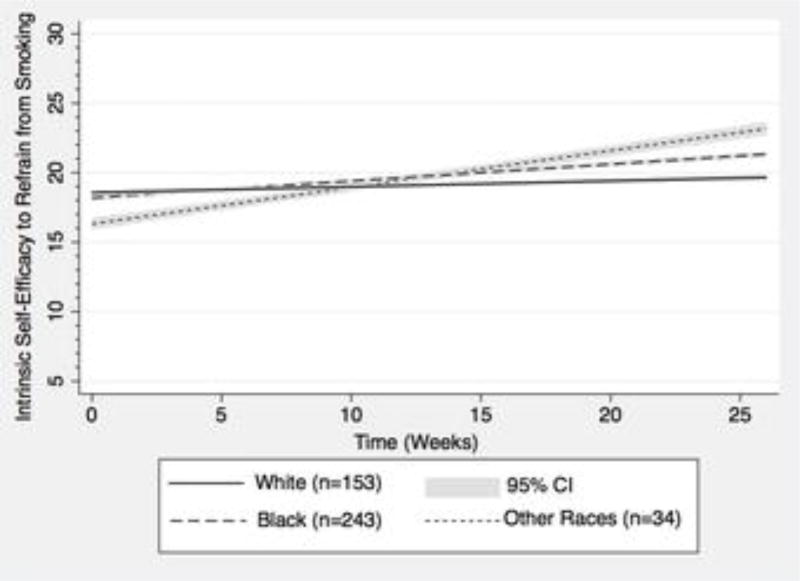

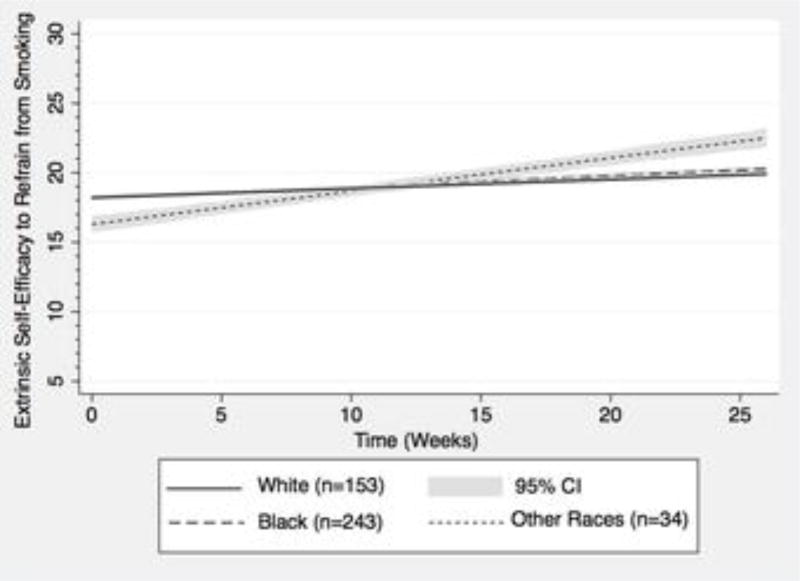

For both intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking, the random intercept, random linear time models provided the best fit to the data. Both intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly over time. Table 2 outlines predictors of change in intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time. Race was the only predictor associated with change in intrinsic (BBlack vs. White = 0.08, p=.037; BOther Race vs. White = 0.22, p=.004) and extrinsic (BOther Race vs. White = 0.17, p=.040) self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time. Treatment group, age, and gender were not associated with change in intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time. Figures 1 and 2 show differences in intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time by race.

Table 2.

Predictors of Change in Intrinsic and Extrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking Over Time among Homeless Smokers in the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

| Intrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking |

Extrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | P-Value | B | SE | P-Value |

|

| ||||||

| Intercept | 17.56 | 0.79 | <.001 | 18.23 | 0.89 | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Time | 0.08 | 0.05 | .123 | 0.09 | 0.06 | .119 |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention treatment group | 0.63 | 0.58 | .283 | 0.61 | 0.66 | .355 |

|

| ||||||

| Intervention treatment group × Time | −0.01 | 0.04 | .856 | −0.01 | 0.04 | .863 |

|

| ||||||

| Traditional Predisposing Components | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Age ≥ 46 | 0.43 | 0.59 | .466 | −0.29 | −0.29 | .664 |

|

| ||||||

| Age ≥ 46 × Time | 0.02 | 0.04 | .627 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .621 |

|

| ||||||

| Male Gender | 0.69 | 0.67 | .307 | −0.21 | −0.21 | .777 |

|

| ||||||

| Male Gender × Time | −0.06 | 0.04 | .184 | −0.04 | −0.04 | .398 |

|

| ||||||

| Social Structure | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Black | −0.47 | 0.63 | .451 | −0.07 | 0.70 | .916 |

| Other | −2.03 | 1.16 | .078 | −2.05 | 1.30 | .115 |

|

| ||||||

| Race × Time | ||||||

| White | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Black | 0.08 | 0.04 | .037 | 0.02 | 0.04 | .703 |

| Other | 0.22 | 0.08 | .004 | 0.17 | 0.08 | .040 |

Note: Age was dichotomized using a median split.

Model fit criteria: Intrinsic AIC: 7205.7; −2LL: 7173.7; Extrinsic AIC: 7465.7; −2LL: 7433.7

Figure 1. Intrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking by Race among Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study Adjusting for Treatment Group, Age, and Gender (N=430).

Change in intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking from baseline to week 26 differed by race. Blacks experienced a greater increase in predicted intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time than Whites. Individuals of other race experienced the greatest increase in predicted intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking.

Figure 2. Extrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking by Race among Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study Adjusting for Treatment Group, Age, and Gender (N=430).

Change in extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking from baseline to week 26 differed by race. Individuals of other race experienced the greatest increase in predicted extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking. Whites and Blacks did not differ in predicted extrinsic-self efficacy to refrain from smoking over time.

Blacks experienced a greater increase in intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time than did Whites. At baseline, Blacks had predicted intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking that was 0.37 lower than Whites (18.19 vs. 18.56); however, at 26-weeks follow-up Blacks had predicted intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking that was 1.67 higher than Whites (21.33 vs. 19.66). Individuals of other race experienced the greatest increase in predicted intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking, from 16.32 at baseline to 23.16 at 26-weeks follow-up. Whites and Blacks didn’t differ in predicted extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time. Individuals of other race experienced a greater increase in predicted extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time from 16.29 at baseline to 22.49 at 26-weeks follow-up. Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 show the average trajectories of intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over time for the full sample.

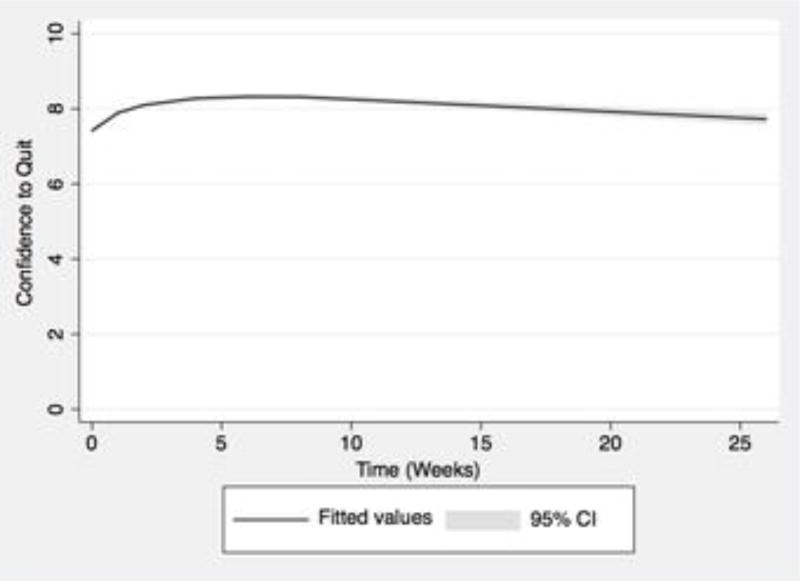

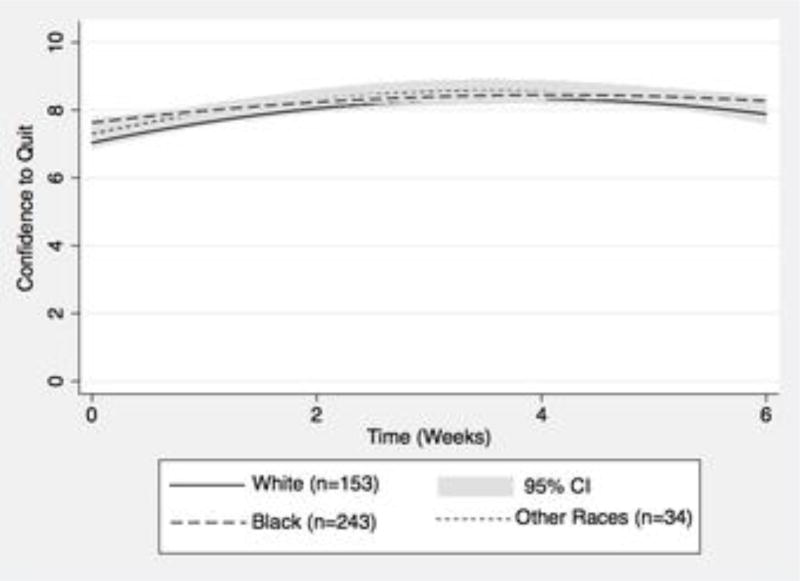

For confidence to quit, the random intercept, random cubic time model provided the best fit to the data. Figure 3 shows the trajectory of confidence to quit over the course of the study, which has a cubic trajectory over time, with increases in confidence to quit during the beginning of treatment and decreases in confidence to quit from the end of treatment (week 8) to 26-weeks follow-up. Since the majority of change in confidence to quit occurred up until week 6, we examined confidence to quit from baseline to week 6. The random intercept, fixed quadratic time model provided the best fit to the data. Confidence to quit increased from baseline to week 4 and decreased from week 4 to week 6. Table 3 outlines predictors of change in confidence to quit from baseline to week 6. Race was the only predictor associated with baseline confidence to quit (BBlack vs. White = 0.62, p=.002), linear change in confidence to quit over time (BBlack vs. White = −0.31, p=.020), and quadratic change in confidence to quit over time (BBlack vs. White = 0.04, p=.040). Treatment group, age, and gender were not associated with change in confidence to quit over time. Figure 4 shows differences in confidence to quit from baseline to week 6 by race.

Figure 3. Confidence to Quit among Homeless Smokers from Baseline to Week 26 of the Power to Quit Study (N=430).

Confidence to quit had a cubic trajectory from baseline to week 26, with increases in confidence to quit during the beginning of treatment and decreases in confidence to quit from the end of treatment (week 8) to 26-weeks follow-up.

Table 3.

Predictors of Change in Confidence to Quit from Baseline to Week 6 among Homeless Smokers in the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

| Variable | B | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intercept | 7.43 | 0.26 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Time | 0.52 | 0.17 | .002 |

|

| |||

| Time2 | −0.07 | 0.03 | .006 |

|

| |||

| Intervention treatment group | −0.14 | 0.19 | .453 |

|

| |||

| Intervention treatment group × Time | 0.19 | 0.12 | .130 |

|

| |||

| Intervention treatment group × Time2 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .429 |

|

| |||

| Traditional Predisposing Components | |||

|

| |||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 46 | −0.35 | 0.19 | .066 |

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 46 × Time | 0.02 | 0.12 | .879 |

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 46 × Time2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .827 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender | −0.21 | 0.22 | .343 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender × Time | 0.10 | 0.14 | .476 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender × Time2 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .469 |

|

| |||

| Social Structure | |||

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | 0.62 | 0.20 | .002 |

| Other | 0.13 | 0.38 | .730 |

|

| |||

| Race × Time | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | −0.31 | 0.13 | .020 |

| Other | 0.04 | 0.24 | .865 |

|

| |||

| Race × Time2 | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | 0.04 | 0.02 | .040 |

| Other | −0.01 | 0.04 | .819 |

Note: Age was dichotomized using a median split.

Model fit criteria: AIC: 7505.0; −2LL: 7465.0

Figure 4. Confidence to Quit by Race among Homeless Smokers from Baseline to Week 6 of the Power to Quit Study Adjusting for Treatment Group, Age, and Gender (N=430).

Change in confidence to quit from baseline to week 6 differed by race. Whites and individuals of other race did not differ in predicted confidence to quit over time. Blacks experienced less change in predicted confidence to quit than Whites and had higher confidence to quit at both early and later points in treatment.

Whites and individuals of other race didn’t differ in predicted confidence to quit from baseline to week 6. However, Blacks experienced less change in predicted confidence to quit than Whites (i.e., their trajectory was ‘flatter’) and had higher confidence to quit at both early and later points in treatment. Compared to Whites, Blacks had 0.59 higher predicted confidence to quit at baseline (7.63 vs. 7.04), 0.12 higher predicted confidence to quit at week 4 (8.45 vs. 8.33), and 0.38 higher predicted confidence to quit at week 6 (8.27 vs. 7.89). Supplementary Figure 3 shows the trajectory of confidence to quit from baseline to week 6 for the full sample.

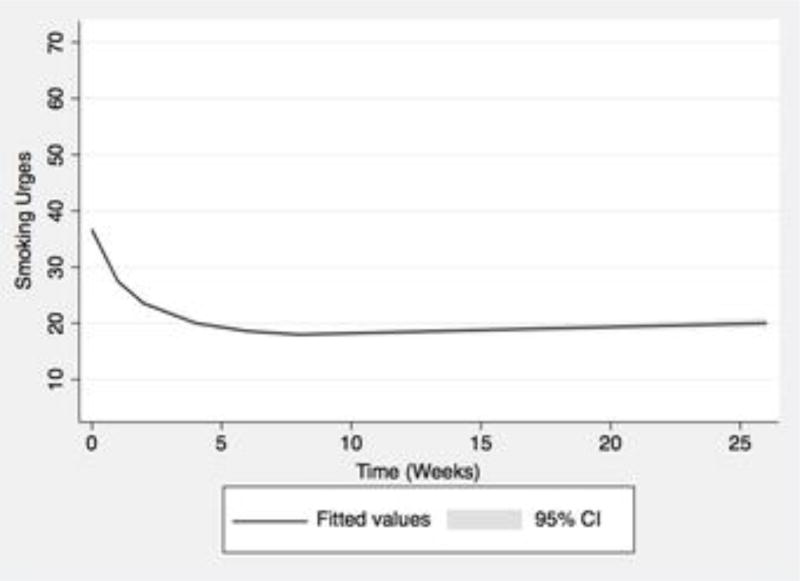

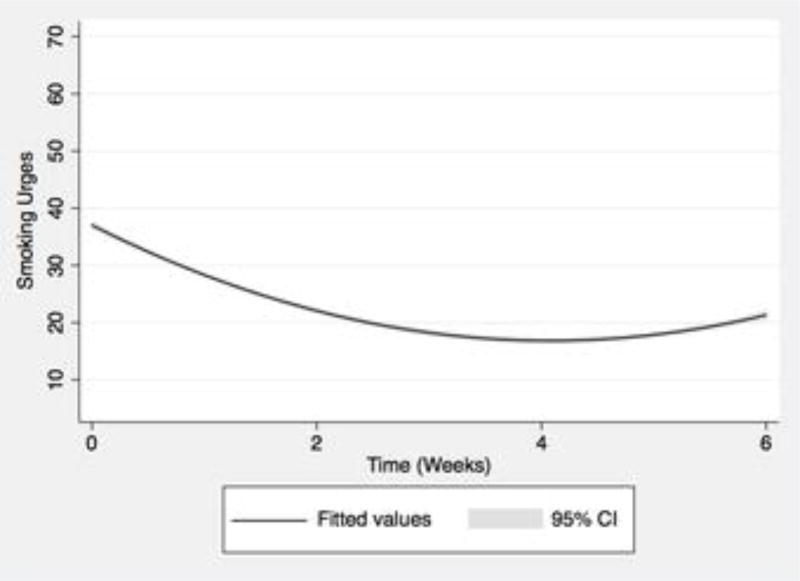

For smoking urges, the random intercept, fixed cubic time model provided the best fit to the data. Figure 5 shows the trajectory of smoking urges over the course of the study, which has a cubic trajectory over time, with decreases in smoking urges during the beginning of treatment and increases in smoking urges from the end of treatment (week 8) to 26-weeks follow-up. Since the majority of change in smoking urges occurred up until week 6, we examined smoking urges from baseline to week 6. The random intercept, fixed quadratic time model provided the best fit to the data. Figure 6 shows the trajectory of smoking urges from baseline to week 6. Smoking urges decreased from baseline to week 4 and increased from week 4 to week 6. Table 4 outlines predictors of change in smoking urges from baseline to week 6. None of the predictors were associated with change in smoking urges over time.

Figure 5. Smoking Urges among Homeless Smokers from Baseline to Week 26 of the Power to Quit Study (N=430).

Smoking urges had a cubic trajectory from baseline to week 26, with decreases in smoking urges during the beginning of treatment and increases in smoking urges from the end of treatment (week 8) to 26-weeks follow-up.

Figure 6. Smoking Urges among Homeless Smokers from Baseline to Week 6 of the Power to Quit Study (N=430).

Smoking urges had a quadratic trajectory from baseline to week 6, with decreases from baseline to week 4 and increases from week 4 to 6.

Table 4.

Predictors of Change in Smoking Urges from Baseline to Week 6 among Homeless Smokers in the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

| Variable | B | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Intercept | 36.98 | 1.82 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Time | −9.98 | 1.30 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Time2 | 1.21 | 0.21 | <.001 |

|

| |||

| Intervention treatment group | −2.14 | 1.35 | .112 |

|

| |||

| Intervention treatment group × Time | −0.30 | 0.96 | .752 |

|

| |||

| Intervention treatment group × Time2 | 0.00 | 0.15 | .992 |

|

| |||

| Traditional Predisposing Components | |||

|

| |||

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 46 | 0.17 | 1.36 | .901 |

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 46 × Time | 0.47 | 0.97 | .630 |

|

| |||

| Age ≥ 46 × Time2 | −0.05 | 0.16 | .754 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender | −0.15 | 1.55 | .923 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender × Time | 0.56 | 1.10 | .613 |

|

| |||

| Male Gender × Time2 | −0.07 | 0.18 | .699 |

|

| |||

| Social Structure | |||

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | 1.41 | 1.44 | .328 |

| Other | 4.53 | 2.67 | .090 |

|

| |||

| Race × Time | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | −0.47 | 1.02 | .647 |

| Other | −2.25 | 1.87 | .229 |

|

| |||

| Race × Time2 | |||

| White | Ref | ||

| Black | 0.09 | 0.17 | .606 |

| Other | 0.35 | 0.30 | .242 |

Note: Age was dichotomized using a median split.

Model fit criteria: AIC: 14887.3; −2LL: 14847.3

4. Discussion

This study examined change in smoking characteristics over the course of the Power to Quit study and predictors of change in smoking characteristics among homeless smokers in the Twin Cities, MN. We found both intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly over the course of the study, which is consistent with studies among other populations that found self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increases from pre-treatment to post-treatment (48–50). New longitudinal findings were Blacks and individuals of other race experienced greater increases in intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over the course of the study than Whites and individuals of other race experienced greater increases in extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking over the course of the study than Whites. These new findings are consistent with cross-sectional research demonstrating racial minorities have higher self-efficacy to quit than Whites (26, 34–36). Cross-sectional studies found reasons for the higher self-efficacy to quit among racial minorities include stronger expectancies that behavioral cessation interventions will help them quit smoking, (34) lower likelihood to expect withdrawal effects, (26) and greater likelihood to expect quitting to be unproblematic (26).

Although self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly over time, general confidence to quit, for which we had data from additional time points throughout the study, increased at the beginning of the study up until week 4 of treatment and then decreased until follow-up. The overall trajectory of confidence to quit is consistent with a previous study among another population that found during treatment confidence to quit increased, but subsequently decreased from post-treatment to follow-up (25). The fact that we see early increases in confidence to quit from baseline to week 4 of treatment is consistent with literature suggesting confidence increases early on during treatment when participants expect treatment will make a positive difference in their lives, in this case help them quit smoking (51). However, confidence to quit can then decrease if individuals experience difficulty quitting (26). In line with our findings for intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking and previous cross-sectional literature, Blacks had higher confidence to quit than Whites (26, 34–36).

As previously found among other populations, confidence to quit and smoking urges had opposite trajectories (24). Smoking urges decreased at the beginning of the study up until week 4 of treatment and then increased until follow-up. Although participants continued to receive nicotine replacement therapy until week 8, there was a drop-off in adherence to wearing the nicotine patch starting at the week 4 study visit (9). While 53% of participants had the nicotine patch on at the week 1 and 2 study visits, at weeks 4, 6, and 8 only 45%, 39%, and 34% of participants were wearing the nicotine patch. This decrease in adherence to the nicotine patch over time may be responsible for the increase in smoking urges starting at week 4 and the decrease in confidence to quit, given strong smoking urges can undermine self-efficacy to quit (30).

A surprising finding was the smoking characteristic trajectories didn’t differ by treatment group. Given that the primary focus of the intervention was encouraging smoking cessation and nicotine patch adherence, and self-efficacy to quit was also targeted, we expected intervention participants to have higher self-efficacy to quit and lower smoking urges. It is possible smoking urges didn’t differ by treatment group due to similar adherence rates in each group.

4.1 Limitations

One limitation is a single item was used to measure confidence to quit; a multi- item measure with superior psychometric properties is preferable. We addressed this by adding the similar measure, self-efficacy to refrain from smoking. However, this measure also has a limitation as it was only measured at three time points and, therefore, we were limited to estimating a linear trajectory for the growth curve analysis. Using both variables in the growth curve analysis gives us a good idea of how self-efficacy to quit changes over the course of the intervention.

A second limitation is there was a very small number of individuals (n=34) who were of other race and these individuals represented several different races/ethnicities including Asian, Hispanic, and Native American. These individuals were all included in one group, which is a limitation since individuals of these races may have different smoking characteristic trajectories.

A third limitation is 25% of data were missing at weeks 6, 8, and 26. For the smoking characteristics, we used all of the available data without any imputation methods since missing at random appears to be a reasonable assumption and there weren’t statistically significant differences in the smoking characteristics at baseline among dropouts and individuals who remained in the study. Individuals who had missing data for smoking status at week 26 were considered smokers.

A forth limitation is that we were required to categorize age in the second phase of the growth curve analysis where we examined differences in the smoking characteristic trajectories by age. By dichotomizing age, we assume that individuals in each age category have the same smoking characteristic trajectory, which may not be true.

A final limitation is our study sample is unlikely to be representative of homeless smokers. Although the study sample was found to be demographically representative of the larger homeless population in Minnesota, the study sample was self-selected for the tobacco cessation study and motivated to quit and thus may not be representative of homeless female smokers generally (9,52).

5. Conclusions

This study extends previous findings on smoking characteristic trajectories to the homeless population; presents new findings on racial differences in self-efficacy to refrain from smoking and confidence to quit over time; and hypothesizes a possible cause of changes in confidence to quit and smoking urges over time. Intrinsic and extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly over the course of the study with greater increases observed among racial minorities. White participants tended to experience a lesser increase in self-efficacy to refrain from smoking and therefore may be a good target for efforts to increase self-efficacy to quit among the homeless as part of smoking cessation interventions.

Confidence to quit increased at the beginning of treatment until week 4 and subsequently decreased until follow-up in all racial groups, but Blacks had higher confidence to quit than Whites. Confidence to quit and smoking urges had opposite trajectories with smoking urges decreasing at the beginning of treatment and then increasing until follow-up. A potential area for future research is to conduct a parallel-process growth model to examine the concurrent relationship between confidence to quit and smoking urges. It is possible lower adherence to the nicotine patch in the second half of treatment may have prompted the changes in confidence to quit and smoking urges; however, further research is needed to test these relationships.

Efforts are needed to rethink homeless-targeted cessation strategies to make them more effective at promoting high self-efficacy to quit and low smoking urges throughout treatment. Although the Power to Quit intervention addressed self-efficacy to quit, it wasn’t a primary focus of the intervention. Homeless-targeted cessation interventions that incorporate self-efficacy to quit-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and/or Motivational Interviewing may have greater success at promoting high levels of self-efficacy to quit (53). In order to promote low smoking urges over time, interventionists could consider offering longer-term treatment. However, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) adherence will also need to be addressed. One strategy to improve medication adherence is to involve patients in treatment decisions (54). Studies could address this by offering participants a choice of NRT. We did not offer participants in the Power to Quit study a choice of NRT, which could have impacted adherence if participants were not satisfied with the provided product. Other strategies for improving medication adherence that could be incorporated into homeless-targeted smoking cessation interventions include providing participants with education on NRT and addressing poor health literacy (54). Incorporating some of these strategies to promote high self-efficacy to quit and low smoking urges throughout smoking cessation treatment could be key to increasing cessation rates among the homeless.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Intrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking among Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

The average trajectory for intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly from baseline to week 26.

Supplementary Figure 2. Extrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking among Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

The average trajectory for extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly from baseline to week 26.

Supplementary Figure 3. Confidence to Quit among Homeless Smokers from Baseline to Week 6 of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

Confidence to quit had a quadratic trajectory from baseline to week 6, with increases from baseline to week 4 and decreases from week 4 to 6.

Highlights.

Self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly over time

Racial minorities had greater increases in self-efficacy to refrain from smoking

Confidence to quit increased until the midpoint of treatment but then decreased

Blacks had higher confidence to quit than Whites

Confidence to quit and smoking urges had opposite trajectories over time

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers R25CA163184 and R01HL081522] and the Veterans Affairs Advanced Fellowship in Clinical and Health Services Research through the Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research. The National Institutes of Health and Department of Veterans Affairs had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health or Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. E. Pinsker designed the study, conducted literature searches and the statistical analysis, and wrote the article. D. Erickson provided statistical consultation. D. Hennrikus, J. Forster, and K. Call provided methodological and content area consultation. K. Okuyemi designed and conducted the parent study.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict declared.

References

- 1.The United States Conference of Mayors. Hunger and Homelessness Survey: A Status report on hunger and homelessness in America's cities. A 27-city survey. [Accessed June 2015];2009 Dec; Available at: https://usmayors.org/pressreleases/uploads/USCMHungercompleteWEB2009.pdf.

- 2.Homelessness Research Institute. The state of homelessness in America 2013. [Accessed July 2015];2013 Available at: http://www.endhomelessness.org/page/-/files/SOH_2013.pdf.

- 3.Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(16):2152–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.16.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O'Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;126(8):625–628. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00007. http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O'Connell JJ, et al. Mortality among homeless adults in Boston: shifts in causes of death over a 15-year period. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(3):189–195. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1604. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelberg L. Health of the Homeless: Definition of the Problem. In: Wood D, editor. Delivering Health Care to the Homeless Persons: The Diagnosis and Management of Medical and Mental Health Conditions. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1992. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggett TP, Rigotti NA. Cigarette smoking and advice to quit in a national sample of homeless adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(2):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.024. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shelley D, Cantrell J, Wong S, Warn D. Smoking cessation among sheltered homeless: a pilot. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2010;34(5):544–552. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.5.4. http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.34.5.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okuyemi KS, Goldade K, Whembolua GL, et al. Motivational interviewing to enhance nicotine patch treatment for smoking cessation among homeless smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2013;108(6):1136–1144. doi: 10.1111/add.12140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.12140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Kesh A, et al. Small financial incentives increase smoking cessation in homeless smokers: a pilot study. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;39(3):717–720. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs-Ericsson N, Wise E, Debrody CP, Paniucki HB. Health problems and service utilization in the homeless. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1999;10:443–452. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0717. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2010.0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferenchick GS. The medical problems of homeless clinic patients: a comparative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1992;7(3):294–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02598086. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02598086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orleans CT, Hutchinson D. Tailoring nicotine addiction treatments for chemical dependency patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1993;10(2):197–208. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(93)90045-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0740-5472(93)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller VF, White MK. Choices and changes: a new model for influencing patient health behavior. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 1997;4(6):33–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curry SJ, Grothaus L, McBride C. Reasons for quitting: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation in a population-based sample of smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22(6):727–739. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00059-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baldwin AS, Rothman AJ, Hertel AW, et al. Specifying the determinants of the initiation and maintenance of behavior change: an examination of self-efficacy, satisfaction, and smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2006;25(5):626–634. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.626. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smit ES, Hoving C, Schelleman-Offermans K, West R, de Vries H. Predictors of successful and unsuccessful quit attempts among smokers motivated to quit. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(9):1318–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Businelle MS, Cuate EL, Kesh A, Poonawalla IB, Kendzor DE. Comparing homeless smokers to economically disadvantaged domiciled smokers. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S218–220. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301336. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiffman S, Engberg JB, Paty JA, et al. A day at a time: predicting smoking lapse from daily urge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(1):104–116. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy DE, Piasecki TM, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Life before and after quitting smoking: an electronic diary study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(3):454–466. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.115.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orleans CT, Rimer BK, Cristinzio S, Keintz MK, Fleisher L. A national survey of older smokers: treatment needs of a growing population. Health Psychology. 1991;10(5):343–351. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Connor SE, Cook RL, Herbert MI, Neal SM, Williams JT. Smoking cessation in a homeless population: there is a will, but is there a way? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17(5):369–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10630.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-002-0042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(4):661–675. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiyko MP, Lanza ST, Tan X, Li R, Shiffman S. Using the time-varying effect model (TVEM) to examine dynamic associations between negative affect and self confidence on smoking urges: differences between successful quitters and relapsers. Prevention Science. 2012;13(3):288–299. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0264-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0264-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boardman T, Catley D, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia JS. Self-efficacy and motivation to quit during participation in a smoking cessation program. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12(4):266–272. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendricks PS, Westmaas JL, Ta Park VM, et al. Smoking abstinence-related expectancies among American Indians, African Americans, and women: potential mechanisms of tobacco-related disparities. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(1):193–205. doi: 10.1037/a0031938. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendricks PS, Delucchi KL, Hall SM. Mechanisms of change in extended cognitive behavioral treatment for tobacco dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109(1–3):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. 1. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berkman ET, Dickenson J, Falk EB, Lieberman MD. Using SMS text messaging to assess moderators of smoking reduction: Validating a new tool for ecological measurement of health behaviors. Health Psychology. 2011;30(2):186–194. doi: 10.1037/a0022201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwaltney CJ, Metrik J, Kahler CW, Shiffman S. Self-efficacy and smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(1):56–66. doi: 10.1037/a0013529. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Etter JF, Prokhorov AV, Perneger TV. Gender differences in the psychological determinants of cigarette smoking. Addiction. 2002;97(6):733–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00135.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stockton MC, McMahon SD, Jason LA. Gender and smoking behavior in a worksite smoking cessation program. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(3):347–360. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00074-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward KD, Klesges RC, Zbikowski SM, Bliss RE, Garvey AJ. Gender differences in the outcome of an unaided smoking cessation attempt. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22(4):521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00063-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4603(96)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cropsey KL, Leventhal AM, Stevens EN, et al. Expectancies for the effectiveness of different tobacco interventions account for racial and gender differences in motivation to quit and abstinence self-efficacy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(9):1174–1182. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Daza P, Cofta-Woerpel L, Mazas C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in predictors of smoking cessation. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41(3):317–339. doi: 10.1080/10826080500410884. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10826080500410884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez E, Tatum KL, Glass M, et al. Correlates of smoking cessation self-efficacy in a community sample of smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(2):175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg CJ, Sanderson Cox L, Mahnken JD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF. Correlates of self-efficacy among rural smokers. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(3):416–421. doi: 10.1177/1359105307088144. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105307088144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnoll RA, Wang H, Miller SM, et al. Change in worksite smoking behavior following cancer risk feedback: a pilot study. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2005;29(3):215–227. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.29.3.3. http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.29.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carter BL, Paris MM, Lam CY, et al. Real-time craving differences between black and white smokers. American Journal on Addictions. 2010;19(2):136–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00020.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2009.00020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pericot-Valverde I, García-Rodríguez O, Gutiérrez-Maldonaldo J, Secades-Villa R. Individual variables related to craving reduction in cue exposure treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;49:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Field M, Duka T. Cue reactivity in smokers: the effects of perceived cigarette availability and gender. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2004;78(3):647–652. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.026. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong C, Bovbjerg DH, Erblich J. Smoking-related videos for use in cue-induced craving paradigms. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3034–3044. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Norman GJ, et al. Does smoking abstinence self-efficacy vary across situations? Identifying context-specificity within the Relapse Situation Efficacy Questionnaire. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(3):516–527. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldade K, Whembolua GL, Thomas J, et al. Designing a smoking cessation intervention for the unique needs of homeless persons: a community-based randomized clinical trial. Clinical Trials. 2011;8(6):744–754. doi: 10.1177/1740774511423947. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1740774511423947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Etter JF, Bergman MM, Humair JP, Perneger TV. Development and validation of a scale measuring self-efficacy of current and former smokers. Addiction. 2000;95(6):901–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9569017.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9569017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200124218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alessi SM, Petry NM. Smoking reductions and increased self-efficacy in a randomized controlled trial of smoking abstinence-contingent incentives in residential substance abuse treatment patients. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(11):1436–1445. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu095. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cupertino AP, Berg C, Gajewski B, et al. Change in self-efficacy, autonomous and controlled motivation predicting smoking. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(5):640–652. doi: 10.1177/1359105311422457. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105311422457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patten CA, Decker PA, Dornelas EA, et al. Changes in readiness to quit and self-efficacy among adolescents receiving a brief office intervention for smoking cessation. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2008;13(3):326–336. doi: 10.1080/13548500701426703. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13548500701426703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Irving LM, Snyder CR, Cheavens J, et al. The relationships between hope and outcomes at the pretreatment, beginning, and later phases of psychotherapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2004;14(4):419–443. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1053-0479.14.4.419. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilder Research. Homelessness in Minnesota: Findings from the 2012 statewide homeless study. [Accessed January 2015];2013 Available at: http://www.wilder.org/Wilder-Research/Publications/Studies/Homelessness%20in%20Minnesota%202012%20Study/Homelessness%20in%20MInnesota%20-%20Findings%20from%20the%202012%20Statewide%20Homeless%20Study.pdf.

- 53.Elshatarat RA, Yacoub MI, Khraim FM, et al. Self-efficacy in treating tobacco use: a review article. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare. 2016;25(4):243–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/2010105816667137. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown MT, Bussell JK. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2011;86(4):304–314. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575. https://doi.org/ 10.4065/mcp.2010.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Intrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking among Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

The average trajectory for intrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly from baseline to week 26.

Supplementary Figure 2. Extrinsic Self-efficacy to Refrain from Smoking among Homeless Smokers Over the Course of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

The average trajectory for extrinsic self-efficacy to refrain from smoking increased linearly from baseline to week 26.

Supplementary Figure 3. Confidence to Quit among Homeless Smokers from Baseline to Week 6 of the Power to Quit Study (N=430)

Confidence to quit had a quadratic trajectory from baseline to week 6, with increases from baseline to week 4 and decreases from week 4 to 6.