Abstract

Background

People with impaired mobility (IM) disabilities have a higher prevalence of obesity and obesity-related chronic conditions; however, lifestyle interventions that address the unique needs of people with IM are lacking.

Objective

This paper describes an adapted evidence-based lifestyle intervention developed through community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Methods

Individuals with IM, health professionals, disability group representatives, and researchers formed an advisory board to guide the process of thoroughly adapting the Diabetes Prevention Program Group Lifestyle Balance (DPP GLB) intervention after a successful pilot in people with IM. The process involved two phases: 1) planned adaptations to DPP GLB content and delivery, and 2) responsive adaptations to address issues that emerged during intervention delivery.

Results

Planned adaptations included combining in-person sessions with conference calls, providing arm-based activity trackers, and adding content on adaptive cooking, adaptive physical activity, injury prevention, unique health considerations, self-advocacy, and caregiver support. During the intervention, participants encountered numerous barriers, including health and mental health issues, transportation, caregivers, employment, adjusting to disability, and functional limitations. We addressed barriers with responsive adaptations, such as supporting electronic self-monitoring, offering make up sessions, and adding content and activities on goal setting, problem solving, planning, peer support, reflection, and motivation.

Conclusions

Given the lack of evidence on lifestyle change in people with disabilities, it is critical to involve the community in intervention planning and respond to real-time barriers as participants engage in change. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is underway to examine the usability, feasibility, and preliminary effectiveness of the adapted intervention.

Keywords: Impaired mobility, healthy lifestyle, obesity, disability

Introduction

People with impaired mobility (IM) remain underserved by public health efforts to address overweight and obesity,1 and effective lifestyle interventions are lacking.1–6 Yet people with disabilities have a higher prevalence of obesity and obesity-related chronic conditions7,8 including a four times higher prevalence of diabetes.7 People with IM are less physically active9 and less likely to receive exercise counseling than people without disability.10 Moreover, the adverse effects of obesity may be greater for people with IM, as excess weight and additional health problems may further restrict functioning and independence.1

While many healthy lifestyle interventions have included people with disabling conditions,2,11,12 fewer have promoted weight loss through both physical activity and diet change specifically among people with IM.13,14 In particular, people with severely impairing neurological conditions such as spinal cord injury, stroke, and multiple sclerosis have been underrepresented in weight loss research.11,15 There is also a growing recognition that unnecessary and costly duplication of programs could be minimized if evidence-based programs are adapted rather than developed de novo.16–19 Building on the findings of a pilot study,20 our research team sought to further adapt an existing healthy lifestyle intervention to address the unique dietary, functional, and environmental needs of people with IM, including those with severe impairment due to neurological conditions.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the modifications identified through a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to adapting the successful Diabetes Prevention Program Group Lifestyle Balance™ (DPP GLB) program into the Group Lifestyle Balance program Adapted for individuals with Impaired Mobility (GLB AIM) program. The goal of both the original and adapted programs is to promote weight loss through an increase in weekly time spent in physical activity and a reduction in daily calorie and fat intake. While the DPP GLB is not explicit in its theoretical basis, the program’s emphasis on self-monitoring, behavioral skills, and environment are consistent with the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT).21 The DPP GLB also incorporates elements of Relapse Prevention22 and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).23 The GLB AIM preserves and extends these theoretical constructs in the context of physical disability. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the GLB AIM to test feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of the adapted intervention is currently underway.

Methods

Original DPP GLB program

The DPP GLB is a direct adaptation of the individualized Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) for delivery by trained coaches in the community. In a three-armed, multi-center RCT the DPP produced significantly greater weight loss, increased PA, and lower incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus than the two arms that received standard lifestyle recommendations along with either the medication metformin or a placebo.24–27 The group-based DPP GLB28,29 has been effective in lowering weight and increasing PA in multiple community settings.30–33 It consists of 12 weekly core in-person sessions, followed by 4 biweekly core transition and 6 monthly support in-person sessions. The program promotes weight loss by limiting calories and being more physically active. Weekly sessions teach behavioral skills and provide accountability for achieving daily calorie and fat gram goals and 150 minutes of moderate PA each week. Skills include goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback, identifying risky situations, relapse prevention skills, and altering environmental cues. To ensure essential intervention components were preserved in the GLB AIM, we formally partnered with the University of Pittsburgh Diabetes Prevention Support Center (DPSC), the organization that ensures fidelity of DPP GLB implementation. The DPP GLB curriculum and materials are available free of charge on the University of Pittsburgh DPSC website (http://www.diabetesprevention.pitt.edu/index.php/for-the-public/for-health-providers/group-lifestyle-balance-curriculum/download-the-dpp-group-lifestyle-balance-curriculum/).

Adaptation Process

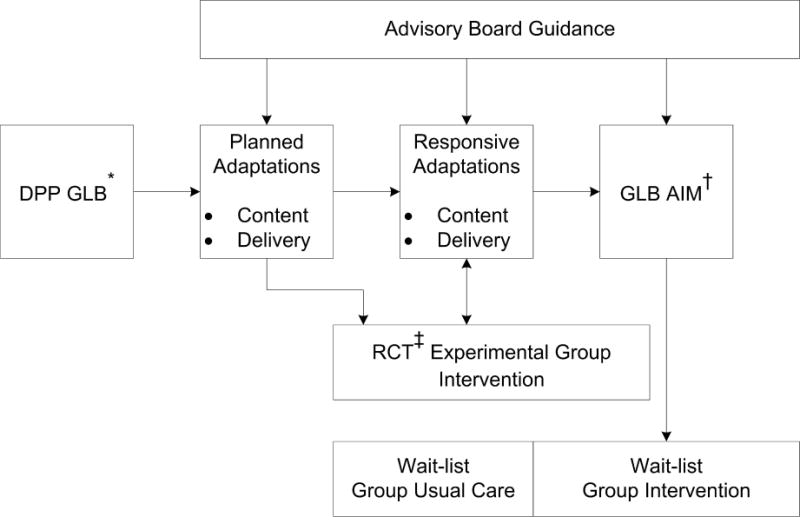

Our aim was to adapt the DPP GLB to be appropriate for individuals with IM, including those with severely impairing neurological conditions. We defined IM as a permanent impairment that limits mobility based on 7 items from the Physical Function section of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.34 Using the CBPR approach of engaging an advisory board, we undertook two adaptation phases: planned and responsive. The 13-member national advisory board consisted of health professionals including physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians, an occupational therapist, and a professor of clinical nutrition; disability researchers specializing in weight loss, built environment, adapted PA, and human and organizational development; and individuals representing community-based disability organizations, including the directors of a local independent living center and an adaptive gym. Five advisory board members had mobility impairments resulting from orthopedic and neurological conditions that required wheelchair use. Figure 1 illustrates our adaptation process. The advisory board directed and participated in making planned content changes and later provided input about adaptations responsive to emergent issues identified during delivery of the intervention.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for process of adapting the DPP GLB* to the GLB AIM†

* Diabetes Prevention Program Group Lifestyle Balance™

† Group Lifestyle Balance Adapted for individuals with Impaired Mobility

‡ Randomized Controlled Trial

Planned adaptations (pre-intervention)

In December 2014, the advisory board convened in person to discuss global issues related to disability and healthy lifestyle and specific modifications to the GLB program, with a focus on the initial 12 core sessions. After the meeting, members convened remote working groups to draft and/or review adapted materials on specific topics. Faculty members of the DPSC participated in advisory board discussions and reviewed and provided input on final versions of all sessions.

After finalizing core sessions, study investigators began an RCT of the one-year program with an intervention group. Participants included individuals with spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, cancer, osteoarthritis, orthopedic problems, and other etiologies that resulted in IM. Participants were recruited in the Dallas/Fort Worth metroplex area of Texas from medical systems, such as University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern) and Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation (BIR); disability service organizations, such as REACH Independent Living Center and the Neuro Fitness Foundation (an accessible gym); and durable medical equipment providers, such as Advanced Mobility Systems of Texas and Lift-Aids. Study flyers were distributed to all of these locations and print advertisements were placed in Ad Pages and Greensheet circulars. Physicians and clinicians at BIR and UT Southwestern discussed the study with patients who met the eligibility criteria.

Responsive adaptations (concurrent with intervention)

During the course of intervention delivery, the study team made responsive, unplanned adaptations to address emergent issues identified through process measures, staff observations, and participant anecdotes. During this phase, the study team examined participants’ engagement (attendance and self-monitoring), formally reported health events, and anecdotally reported barriers to program adherence. The principal investigator, co-investigators, and interventionists met monthly to discuss barriers and devise responsive adaptations to address them. The advisory board reconvened by phone in June 2016 to provide guidance on the issues faced during intervention months 4–9 and recommended corresponding adaptations to the remaining sessions.

Results

Planned adaptations (pre-intervention)

The advisory board recommended changes to program delivery and content. The GLB AIM topics for each session and adaptations are in Table 1.

Table 1.

GLB AIM* session schedule, topics, theories and constructs, original DPP GLB† summaries, and revision summaries

| Month + meeting schedule | Session # | Topic | Theory & Constructs | DPP GLB Content | GLB AIM Revision (content or wording) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 weekly (core) | 1 (in-person) | Welcome to the GLB Program |

SCT‡ facilitation, self-regulation (goal setting & self-monitoring) |

Build program commitment & highlight program goals of (a) targeting 5%–7% weight loss and (b) doing 150 minutes of weekly physical activity + discuss lifestyle coach role to support participants efforts & introduce self-monitoring of food intake. | Planned adaptations New content

|

| 2 | Be a Fat and Calorie Detective |

SCT self-regulation (self-monitoring & goal setting) |

Focus on finding the main sources of dietary fat by monitoring fat grams using the “DPP Fat Counter” & by reading food labels. Practice measuring & weighing food. Teach 3 ways to eat less fat: eat high-fat foods less often, eat smaller portions, and substitute lower fat foods and cooking methods. Assign a fat gram goal based on starting weight. | Responsive adaptations Revised Content/Delivery

|

|

| 3 | Healthy Eating |

SCT self-monitoring |

Discuss eating patterns and introduce the USDA’s§ “My Plate” as a model for healthy eating. Emphasize low-fat, low-calorie foods and serving size and how to choose healthier fats. | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 4 | Move Those Muscles |

SCT self-monitoring goal setting |

Introduce physical activity and benefits of active lifestyle. Discuss building to 150 minutes of activity over the next 4 weeks. Discuss safety issues. Begin self-monitoring of physical activity plus food intake. Review personal activity history and likes and dislikes about physical activity. | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 2 weekly (core) | 5 | Tip the Calorie Balance |

SCT self-monitoring self-efficacy |

Teach the principle of energy balance and what it takes to lose 1–2 lbs per week. For people who have made little weight loss progress, may provide a structured meal plan at reduced calorie levels. | Planned adaptations New content

|

| 6 (in-person) | Get Comfortable in the Kitchen |

SCT observational learning facilitation self-efficacy |

NEW session | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 7 | Take Charge of What’s Around You |

SCT reciprocal determinism self-monitoring cues self-efficacy |

Introduce the principle of stimulus control. Identify cues in the participant’s home environment that lead to unhealthy food and activity choices and discuss ways to change them. | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 8 | Problem Solving |

SCT self-monitoring problem solving |

Present the 5-step model of problem solving: describe the problem as links in a behavior chain, brainstorm possible solutions, pick one solution to try, make a positive action plan, evaluate the success of the solution. Apply the problem-solving model to eating and exercise problems. | Planned adaptations Revised content

|

|

| 3 weekly (core) | 9 | Four Keys to Healthy Eating Out |

SCT self-monitoring self-efficacy |

Introduce 4 skills for managing eating away from home: anticipating and planning ahead, positive assertion, stimulus control, and making healthy food choices. | No substantive changes to content |

| 10 | Slippery Slope of Lifestyle Change |

SCT self-monitoring facilitation Relapse Prevention goal setting |

Stress that slips are normal and learning to recover quickly is the key to success. Teach participants to recognize personal triggers for slips, identify their reactions to slips, replacing negative thoughts with positive self-talk; and getting back on track. | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 11 (in-person) | Jump Start Your Activity Plan |

SCT problem solving goal setting |

Provide pedometer. Introduce the basic principles of aerobic fitness: frequency, intensity, time, type of activity (FITT). Teach participants about measuring exercise intensity with heart rate and perceived level. Discuss adding variety to the physical activity plan to prevent boredom. | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 12 | Make Social Cues Work for You |

SCT self-monitoring cues social support |

Present strategies for managing problem social cues, e.g., being pressured to overeat, and help participants use social cues to promote healthy behaviors, e.g., making regular dates with a walking partner or group. Review specific strategies for coping with social events such as parties, vacations, and holidays. | Planned adaptations New content

|

|

| 13 | Ways to Stay Motivated |

SCT self-monitoring rewards social support CBT¶ coping |

Enhance motivation to maintain behavior change by reviewing participants’ personal reasons for joining GLB and by recognizing personal successes. Introduce other strategies for staying motivated including posting signs of progress, setting new goals, creating friendly competition, and seeking social support from staff and others. | Planned adaptations New Content

|

|

| 4 biweekly (support) | 14 (in-person) | Preparing for Long-Term Self-Management |

SCT self-management, contract |

Discuss transition to less frequent meetings, describe benefits of continued attendance, renew commitment to GLB program. | Planned adaptations Revised content

|

| 15 | More Volume, Fewer Calories |

SCT self-efficacy facilitation |

Learn 4 ways to reduce calories by adding volume to meals: reduce fat, add water, add fiber, add fruits/vegetables. Discuss recipes for adding volume & identify characteristics of healthy choice for breakfast cereal. | Planned adaptations Revised content

|

|

| 16 (in-person) | Balance Your Thoughts for Long-Term Self-Management |

CBT increase awareness of self-talk change response SCT self-management self-efficacy |

Reflect on weight management behaviors for long-term and impacts of weight loss to life. Rank personal reasons for persisting in weight management efforts. Identify negative-thoughts and practice countering with more helpful and effective responses. | Planned adaptations Revised content

|

|

| 5 monthly (support) | 17 (in-person) | Strengthen Your Exercise Program |

SCT observational learning self-efficacy facilitation |

Discuss benefits of resistance training, recognize safety issues, including proper form and technique. | Planned adaptations New content

|

| 6 monthly (support) | 18 (in-person) | Mindful Eating |

SCT facilitation self-efficacy |

Analyze and describe current eating behaviors, define mindful eating and negative effects of mindless eating. Discuss benefits of eating slowly & mindfully + practice this technique with food. | Responsive adaptations New content

|

| 7 monthly (support) | 19 (in-person) | Stress and Time Management |

SCT self-efficacy self-regulation CBT increase awareness of thoughts change responses |

Discuss how stress affects lifestyle habits, plus identify healthy and unhealthy coping strategies. Discuss ways to take charge of stress and how to reduce, prevent, or manage stress. Practice relaxation techniques and discuss tips for improving sleep. | Responsive adaptations New content

|

| 8 monthly (support) | 20 (in-person) | Stretching: The Truth about Flexibility |

SCT observational learning facilitation self-efficacy |

Review 4 components of exercise program: endurance, aerobic, strength, flexibility. Discuss importance of flexibility and techniques for safe stretching including proper form and technique. | Planned adaptations New content

|

| 9 monthly (support) | 21 (in-person) | Heart Health |

SCT outcome expectations |

Discuss heart disease prevalence, risk-factors (blood pressure and cholesterol), and the role diet and exercise play in reducing risk. | Planned adaptations Revised content

|

| 10 monthly (support) | 22 (in-person) | Power Up: Harnessing What You Have Learned |

SCT Self-efficacy, peer modeling, social support |

NEW session, replaced “Stand Up for Your Health” | Responsive adaptations New content

Revised content

|

| 11 monthly (support) | 23 (in-person) | Looking Back and Looking Forward |

SCT reciprocal determinism social support self-efficacy |

Discuss shift in thinking patterns useful for weight loss. Describe behaviors of those who maintain weight loss. Spend time reflecting and writing their personal healthy life story. Discuss critical foundation behaviors for maintaining weight loss. | Planned adaptations New content

|

Group Lifestyle Balance Adapted for individuals with Impaired Mobility

Diabetes Prevention Program Group Lifestyle Balance™

Social Cognitive Theory

United States Department of Agriculture

Multiple sclerosis

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Program delivery

The original DPP GLB curriculum is delivered in-person for all 22 sessions. One advisory board recommendation was to alternate phone-based and in-person sessions to alleviate persistent transportation barriers faced by people with IM. Results published from a small pilot study we previously conducted20 supported the acceptability of a teleconference format for individuals with IM. While the board supported a mixed delivery approach for the weekly core sessions, they believed in-person interaction over subsequent sessions (months 4–12) was important to enhance peer support and provide an opportunity to weigh, given limited availability of wheelchair-accessible scales in the community. They agreed that a monthly in-person meeting would be feasible for participants.

The board also recommended incorporating technology by (1) providing arm-based activity trackers rather than pedometers, because pedometers do not capture movement in a wheelchair; (2) using mobile applications to self-monitor diet and PA; and (3) creating a study Facebook page to facilitate communication among participants. Finally, the board recommended inviting caregivers to attend program sessions, given their high involvement in daily activities (e.g., transportation, food preparation) for participants with severe impairment.

Content

The board recommended thoroughly revising the core program materials to make language and examples “disability friendly” and to incorporate substantial new content. Changes were made to all sessions, but the most substantial content changes focused on (1) adding a session on adaptive cooking and (2) considerably revising the content on PA, to explicitly address accessibility issues. The board helped develop the adaptive cooking content, with topics including kitchen modifications, adaptive cooking tools, accessible low-fat cooking methods, kitchen safety, saving time and money, accessible grocery, shopping, and resources. The board also assisted with substantially revising the PA sessions (sessions 4, 11) to address adapted PA, including home-based activities (e.g., neighborhood wheeling, arm ergometers, exercise videos, resistance bands and other home equipment) and community-based activities (e.g., gyms, water exercise, kayaking, adapted sports). An accessibility checklist and guidelines for gradual progression to meet the 150-minute weekly goal were added, consistent with the most recent national PA recommendations (17). Supplemental materials were developed to further address planning and safety, diagnosis-specific issues, adaptive equipment, local places to be active, and resources.

Other key content additions included guidance on unique health considerations, such as preventing pressure ulcers and urinary tract infections, preventing overuse injury, and expecting changes to bowel and bladder programs, all in the context of lifestyle change. Revised materials also included guidance on staying healthy in the hospital and getting back on track after a health event. A handout for caregivers discussed how to help with healthy lifestyle (e.g., be a cheerleader, not a coach) and how to take care of their own needs (e.g., set realistic goals, seek support, use relaxation techniques). Advisory board members authored these new materials, which were incorporated into existing sessions.

Responsive adaptations (concurrent with intervention)

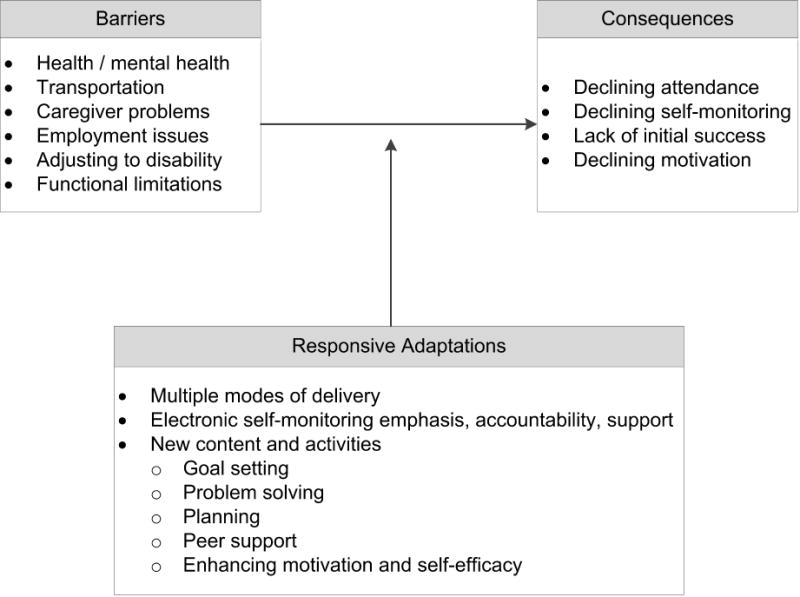

During monthly team meetings the study team reviewed empiric and anecdotal evidence of issues affecting engagement as measured by participants’ weekly meeting attendance and dietary self-monitoring (rates will be reported with the results of the RCT). A number of participants anecdotally reported facing disability-related barriers to engaging in program activities and intervention recommended behaviors. Barriers included health events, such as pressure ulcers, surgeries, and procedures; and mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and panic attacks. Other noted barriers included transportation, caregivers, employment and financial issues, and adjustment to disability. The team discussed methods to reduce barriers and improve program engagement. Figure 2 summarizes how responsive adaptations were intended to moderate the relationship between barriers participants experienced and negative consequences.

Figure 2.

Summary of barriers, consequences, and responsive adaptations

Content

The study team developed responsive content adaptations to enhance participant motivation and self-efficacy. First the team added a group-based problem solving and planning activity to address emergent barriers. This activity, which coincided with session 18 (originally session 17), guided participants in using the DPP GLB’s problem solving and planning approach to address disability-specific barriers and create new short-term goals. Lifestyle coaches followed up on these goals, providing additional accountability.

Second, the advisory board recommended modifying the session on reducing sedentary behavior (GLB AIM session 22; DPP-GLB session 19) to focus on enhancing motivation and self-efficacy for healthy lifestyle. Using the advisory board’s input, the study team rewrote the session to focus on the mastery experience. Specifically, the content guided participants in identifying past successes, skills gained, unique facilitators, and personal strengths. To accomplish this, the new session utilized personal reflection, peer support, and planning exercises.

Coaches reiterated key GLB AIM skills over the final sessions as participants reported problems. These included self-advocacy (e.g., speaking up for one’s needs in the community and with caregivers, finding compromise); problem-solving around common barriers (e.g. transportation, limited time with caregivers); and relapse prevention techniques for dealing with health events or other setbacks (e.g. managing stress, staying healthy in the hospital, protecting time set aside for healthy lifestyle while recuperating, restarting PA progression after physical recovery). To encourage engagement and enhance self-efficacy for stress management and PA at home, the team added two activities to in-person sessions: wheelchair yoga and wheelchair dance.

Program delivery

The planned delivery options for participants unable to attend one or more sessions included (a) inviting individuals to call in to the session, (b) making available the original DPP GLB DVDs, as well as (c) providing audio recordings of each session. To further address transportation barriers, declining attendance at the in-person sessions, and low uptake of the options offered above, the team began offering make-up conference calls for in-person sessions, beginning with session 18 in the intervention group.

To address low self-monitoring adherence, the team responded by encouraging and facilitating use of a mobile application to track food and PA daily, beginning with session 17 in the intervention group. While the original DPP GLB offers participants the option to track by paper or using a mobile application, the original program does not specifically encourage or support applications. Participant feedback and staff observation indicated that cell phones were physically and logistically easier for participants to manage than calorie books and paper journals. For example, some participants’ impairments involved arm, hand, and finger function. Mobile applications also offered stronger accountability, as lifestyle coaches were able to view participant diaries in real-time.

A wait-list control group received the full GLB AIM intervention, including all planned and responsive adaptations to program delivery and content (see Figure 1).

Integrity and theory of the GLB AIM program

In creating the GLB AIM, the advisory board and DPSC collaboration helped ensure essential components of the DPP GLB were retained throughout the adaptation processes. The DPP GLB target behaviors of self-monitoring and meeting daily calorie and fat gram goals, and self-monitoring and achieving a minimum of 150 minutes per week of moderate-vigorous PA were preserved. The target behavior of regular self-weighing was encouraged for those who could safely stand or who had access to wheelchair accessible scales. While DPP GLB content was modified and new content was added, no content was eliminated. DPP GLB pedagogy was retained with the exception of weekly weigh-ins during the core sessions, given the reduced frequency of in-person sessions due to transportation barriers. Aside from the addition of one session on adaptive cooking, the recommended DPP GLB sequence, schedule, and dosing was retained. Finally, the GLB AIM preserved and extended the theoretical underpinnings of the original DPP GLB in the context of disability. Table 1 provides an overview of the theories and theoretical constructs that apply to each of the GLB AIM sessions.

Discussion

This paper describes the process used to identify needed modifications to adapt an evidence-based lifestyle program to suit the needs of people with IM. Strengths of our process included incorporating a CBPR approach to assure targeted and appropriate planned adaptations, and addressing the experiences of people with IM as they engaged with the intervention through responsive adaptations. Although anticipated, barriers including health events, transportation, caregiver and employment issues, adjusting to disability, and functional limitations emerged as persistent barriers requiring responsive adaptations. Future healthy lifestyle intervention efforts for people with physical disabilities must thoroughly address these barriers. Finally, articulating the theoretical basis for the GLB AIM clarifies proposed mechanisms of behavior change.

Our method of adapting the DPP GLB (planned and responsive adaptations) followed the general guidelines of the Department of Health and Human Services recommendations for adapting evidence based programs (available at https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fysb/prep-making-adaptations-ts.pdf) and some aspects of the Guidelines, Recommendations, Adaptations Including Disability (GRAIDs).17 Although the staff did not conduct focus groups, a pilot study of a modified DPP GLB established preliminary feasibility and usability among people with IM.35 The GLB AIM also incorporated aspects of individual behavioral weight loss treatment;36 however, the group-based format of the GLB AIM may offer a more cost-effective approach with potentially greater reach than individual lifestyle change programs.28,29 Furthermore, the group format provides an avenue for social support from other people with disabilities, which may help buffer stress associated with lifestyle change37 as well as depression,38 a commonly reported barrier in our study.

A limitation to our approach was the lack of a formal mechanism for incorporating ongoing participant feedback to inform responsive adaptations. Although we engaged the advisory board in making decisions during the program and participants provided a summative program evaluation after program completion, additional insight into participant barriers and potential solutions could be achieved by including a participant representative in team meetings or regularly surveying participants. Use of the rigorous Participatory Action Research framework would help assure community engagement and promote sustainability by involving people with disabilities in making all final study decisions.39–41

There is an urgent need to test and implement healthy lifestyle interventions for people with IM, who face a higher prevalence of obesity and related chronic conditions and greater barriers to healthy lifestyle. A strength of the GLB AIM is its potential to develop an evidence base for intervention in both community and clinical settings, as the original DPP GLB has demonstrated effectiveness in these settings. Moreover, the original DPP GLB is publicly accessible through the Creative Commons Agreement and is supported by the DPSC. Thus the GLB AIM may be a viable intervention strategy for health care systems and communities to address the obesity epidemic in people with IM. Forthcoming feasibility and effectiveness data from the RCT will inform future interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our advisory board members, Ross Brownson, PhD, Dot Nary, PhD, Anjali Forber-Pratt, PhD, Kiyoshi Yamaki, PhD, Catana Brown, PhD, OTR, FAOTA, Elaine Jackson, PT, PhD, Rita Hamilton, DO, Lona Sandon, MEd, RDN, LD, Seema Sikka, MD, Danielle Melton, MD, Chris Mackey, Charlotte Stewart, and Shelby Lauderdale for their time and work in adapting the GLB AIM program. We would also like to extend a warm thank you to our study participants.

Funding Disclosures:

This publication was supported by the Disability and Research Dissemination Center (DRDC) through its Grant Number 5U01DD001007, FAIN No. U01DD001007 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The following refers to Andrea Betts - Predoctoral Fellowship, University of Texas School of Public Health Cancer Education and Career Development Program – National Cancer Institute/NIH Grant R25 CA57712. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the DRDC, the CDC, or National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures:

None of the authors have any competing interests or financial benefits.

References

- 1.Froehlich-Grobe K, Lollar D. Obesity and disability: Time to act. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(5):541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cervantes CM, Taylor WC. Physical activity interventions in adult populations with disabilities: A review. Quest. 2011;63(4):385–410. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nery MB, Driver S, Vanderbom KA. Systematic framework to classify the status of research on spinal cord injury and physical activity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(10):2027–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanderbom KA, Driver S, Nery-Hurwit M. A systematic framework to classify physical activity research for individuals with spina bifida. Disability and Health Journal. 2014;7(1):36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon-Ibarra A, Driver S, Dugula A. Systematic framework to evaluate the status of physical activity research for persons with multiple sclerosis. Disability and Health Journal. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Henson S, Jackson A, Richards J. Obesity intervention in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal cord. 2006;44(2):82–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Froehlich-Grobe K, Lee J, Washburn RA. Disparities in obesity and related conditions among Americans with disabilities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;45(1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rasch EK, Hochberg MC, Magder L, Magaziner J, Altman BM. Health of community-dwelling adults with mobility limitations in the United States: Prevalent health conditions. Part I. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity among adults with a disability-United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56(39):1021–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weil E, Wachterman M, McCarthy EP, et al. Obesity among adults with disabling conditions. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(10):1265–1268. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plow MA, Moore S, Husni ME, Kirwan JP. A systematic review of behavioural techniques used in nutrition and weight loss interventions among adults with mobility-impairing neurological and musculoskeletal conditions. Obesity reviews. 2014;15(12):945–956. doi: 10.1111/obr.12223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuifbergen AK, Morris M, Jung JH, Pierini D, Morgan S. Benefits of wellness interventions for persons with chronic and disabling conditions: a review of the evidence. Disability and health journal. 2010;3(3):133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rimmer JH, Rauworth A, Wang E, Heckerling PS, Gerber BS. A randomized controlled trial to increase physical activity and reduce obesity in a predominantly African American group of women with mobility disabilities and severe obesity. Preventive Medicine. 2009;48(5):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reichard A, Saunders MD, Saunders RR, et al. A comparison of two weight management programs for adults with mobility impairments. Disabil Health J. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rejeski W, Marsh A, Chmelo E, Rejeski J. Obesity, intentional weight loss and physical disability in older adults. Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal Of The International Association For The Study Of Obesity. 2010;11(9):671–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drum CE, Peterson JJ, Culley C, et al. Guidelines and criteria for the implementation of community-based health promotion programs for individuals with disabilities. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;24(2):93–101. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090303-CIT-94. ii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rimmer JH, Vanderbom KA, Bandini LG, et al. GRAIDs: a framework for closing the gap in the availability of health promotion programs and interventions for people with disabilities. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0100-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison MB, Graham ID, van den Hoek J, Dogherty EJ, Carley ME, Angus V. Guideline adaptation and implementation planning: A prospective observational study. Implement Science. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betts AC, Froehlich-Grobe K. Accessible weight loss: Adapting a lifestyle intervention for adults with impaired mobility. Disability and Health Journal. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: Social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse prevention and the maintenance of optimal health. New York: Springer publishing company; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kriska A. Can a physically active lifestyle prevent type 2 diabetes? Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2003;31(3):132–137. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, et al. Achieving weight and activity goals among diabetes prevention program lifestyle participants. Obesity Research. 2004;12(9):1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2102–2107. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kriska AM, Edelstein SL, Hamman RF, et al. Physical activity in individuals at risk for diabetes: Diabetes Prevention Program. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(5):826–832. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000218138.91812.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kramer MK, Kriska AM, Venditti EM, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program: a comprehensive model for prevention training and program delivery. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(6):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kramer MK, McWilliams JR, Chen HY, Siminerio LM. A community-based diabetes prevention program: evaluation of the group lifestyle balance program delivered by diabetes educators. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(5):659–668. doi: 10.1177/0145721711411930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dodani S, Kramer MK, Williams L, Crawford S, Kriska A. Fit body and soul: a church-based behavioral lifestyle program for diabetes prevention in African Americans. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19(2):135–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis-Smith YM, Boltri JM, Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Blalock T, Tobin B. Implementing a diabetes prevention program in a rural African-American church. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(4):440–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amundson HA, Butcher MK, Gohdes D, et al. Translating the diabetes prevention program into practice in the general community: findings from the Montana Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(2):209–210. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333269. 213-204, 216–220 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Physical Function items of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/spq-pf.pdf; 1999–2000. Accessed February 10, 2017.

- 35.Betts AC, Froehlich-Grobe K. Accessible weight loss: Adapting a lifestyle intervention for adults with impaired mobility. Disability and Health Journal. 2017;10(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almirall D, Nahum-Shani I, Sherwood NE, Murphy SA. Introduction to SMART designs for the development of adaptive interventions: With application to weight loss research. Translational behavioral medicine. 2014;4(3):260–274. doi: 10.1007/s13142-014-0265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suh Y, Weikert M, Dlugonski D, Sandroff B, Motl R. Physical activity, social support, and depression: Possible independent and indirect associations in persons with multiple sclerosis. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2012;17(2):196–206. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.601747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Müller R, Peter C, Cieza A, Geyh S. The role of social support and social skills in people with spinal cord injury–a systematic review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(2):94–106. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White GW, Nary DE, Froehlich AK. Consumers as collaborators in research and action. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2001;21(15–34) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seekins T, White GW. Participatory action research designs in applied disability and rehabilitation science: protecting against threats to social validity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94(1 Suppl):S20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White GW. Consumer participation in disability research: The golden rule as a guide for ethical practice. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2002;47(4):438. [Google Scholar]