Abstract

Rationale:

Lymph node is a preferred site for extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB). In the thorax, mediastinal tuberculous lymph nodes can erode adjacent structures such as heart, aorta, and esophagus, forming fistula, and causing fatal consequences. However, tuberculous bronchonodal fistula as a complication of lymph node TB in adults is rarely known in terms of imaging or clinical findings. Here, a case of isolated tuberculous bronchonodal fistula appearing as the first presentation of TB in a 74-year-old male with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is reported.

Patient concern:

A 74-year-old male with SLE visited the hospital with dry cough. In family history, his son was treated for pulmonary TB 9 years previously. Laboratory test revealed increased C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a necrotic lymph node in the right hilar area connected to the inferior wall of the right upper lobe bronchus and the lateral wall of bronchus intermedius.

Diagnoses:

On bronchoscopy performed under guidance of 3-dimensionally reconstructed CT image, fistula formation between the right hilar lymph node and 2 bronchi (the right upper lobe and intermediate bronchus) was confirmed. Sputum culture revealed growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Intervention:

Anti-TB medication with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and moxifloxacin for 9 months.

Outcome:

The patient's symptom was gradually improved. Follow-up bronchoscopy performed at 3 months after starting the medication revealed decreased size of the fistula.

Lessons:

This is a rare case of bronchonodal fistula appearing as the first presentation of TB in a 74-year-old male patient with SLE. CT provided useful information regarding the origin and progress of the disease.

Keywords: bronchonodal fistula, endobronchial tuberculosis, lymph node, SLE, tuberculosis

1. Introduction

Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have increased risk of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis (TB) due to intrinsic and extrinsic immune suppression.[1] Lymph node TB is the most common form of extrapulmonary TB. In the chest, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can enter the lymphatic system from parenchymal lesions and cause mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy due to caseation necrosis and granulation tissue formation.[2] Tuberculous lymph nodes in the mediastinum can erode adjacent structures, including esophagus, heart, aorta, and airways through inflammation and necrosis, causing fatal consequences sometimes.[3–6]

Airway involvement by enlarged TB lymph nodes occurs mostly in children who have small-caliber airways. Bronchial compression and bronchonodal fistula formation by enlarged mediastinal/hilar TB lymph nodes in children with active pulmonary TB have been reported previously.[7,8] However, to the best of our knowledge, tuberculous bronchonodal fistula in adult patient, particularly in those without concomitant parenchymal lesion, has not been reported yet.

Herein, a case of tuberculous bronchonodal fistula occurring in a 74-year-old male patient with SLE as the first presentation of TB is reported, emphasizing the important role of chest computed tomography (CT) in diagnostic process and understanding the pathogenesis of tuberculous bronchonodal fistula.

2. Case report

Informed consent for publishing this report and any accompanying images was obtained from the patient. A 74-year-old male farmer visited our hospital due to stiffness and progressive deformity of finger joints dating back 10 years. His father had the same problem. He thought their symptoms were due to long-term farm working. On physical examination, his conjunctivae appeared pale. There were ulcers in the oral cavity. Laboratory examination showed leukopenia (3900/mm3) with increased C-reactive protein level (40.7 mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (104 mm/h). Tests for detecting autoantibodies such as fluorescent antinuclear antibody (1:160), anti-ds DNA IgG, and anti-cardiolipin IgG were positive. After all evaluations, the patient was diagnosed with SLE. Chest CT scan showed emphysematous change in lungs and a few borderline-sized or enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinum and hilar area (Fig. 1). There was no interstitial lung disease or active parenchymal lesion. He started medications for SLE with oral corticosteroid (prednisolone), 10 mg daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg daily.

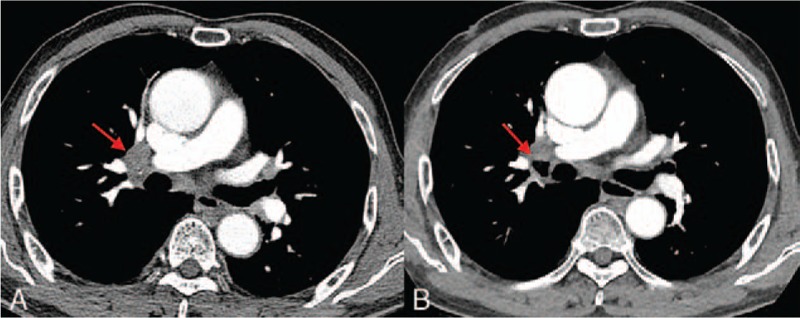

Figure 1.

(A) Initial chest CT showing an enlarged lymph node in the right hilar area (arrow). Smaller lymph nodes are also seen in subcarinal and left hilar areas. (B) Follow-up chest CT taken 3 months later showing increased right hilar lymph node with cavity formation (arrow).

Three months later, the patient visited the hospital with dry cough that lasted 2 weeks. Laboratory test revealed increased C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The physician suspected pneumonia. Since there were no obvious infiltrates on chest radiographs, chest CT scan was performed. Chest CT scan showed a cavity in the right hilar area in which an enlarged lymph node was on noted initial chest CT. The cavity was connected to the inferior wall of the right upper lobe bronchus and the lateral wall of bronchus intermedius on 3-dimensionally reconstruction image (Fig. 2). There was no parenchymal lesion suggestive of active pulmonary TB draining into the bronchus. Bronchoscopy was recommended with a suspicion of bronchonodal fistula. However, one of the fistulas was missed on the initial examination. On repeat bronchoscopy performed after reviewing CT images, focal mucosal defects covered with necrotic tissue were noted at the right upper lobe bronchus and bronchus intermedius, corresponding to the location of bronchial fistula on CT (Fig. 3). Caseous material draining into bronchus was seen. Bronchial mucosa was clear in other areas. Polymerase chain reaction using bronchial aspirate and sputum culture revealed M tuberculosis. In family history, his son was treated for pulmonary TB 9 years previously. Since drug sensitivity testing showed resistance to rifampin, anti-TB medication was started with isoniazid 300 mg daily, ethambutol 800 mg daily, pyrazinamide 1500 mg daily, and moxifloxacin 400 mg daily. Dry cough was improved in 2 weeks after beginning the treatment. Now, the patient is under treatment for 6 months on a 9-month course of medication. Follow-up bronchoscopy performed at 3 months after starting the medication revealed decreased size of fistula. Although medication for SLE has stopped with the starting of anti-TB treatment, SLE-associated symptoms are stable.

Figure 2.

(A and B) Coronal reformatted images with lung window setting revealing cavity in the right hilar lymph node and connecting channels with the inferior wall of the right upper lobe bronchus (arrow in A) and the lateral wall of the bronchus intermedius (arrow in B). (C) Volume rendered 3-dimensional image of tracheobronchial tree showing crescentic air collection within the right hilar lymph node connected with 2 adjacent bronchi (arrows).

Figure 3.

Bronchoscopic image of the right upper lobe bronchus (A) and bronchus intermedius (B) showing focal mucosal defects covered with necrotic material.

3. Discussion

SLE is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease. Its estimated prevalence ranges from 16 to 70 per 100,000 persons.[9] Infection is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with SLE.[10] In particular, the risk of TB has been reported to be 5- to 60-fold higher in patients with SLE than that in those without SLE.[11] Their susceptibility to TB can be explained by immunologic disturbance intrinsic to SLE, long-term administration of immunosuppressive drugs such as corticosteroids, and cross-reactivity between mycobacterial cell wall glycolipids and antinuclear antibody.[11–13]

This is a rare case of bronchonodal fistula appearing as the first presentation of TB in a 74-year-old male patient with SLE. Initial or follow-up chest CT of the patient did not show pulmonary TB. TB involving lymph nodes showed nonspecific findings on initial CT for this patient. In addition, the patient did not complain of any TB-related symptoms. Therefore, the diagnosis was established relatively late during the course of disease, when the fistula had already formed between the right hilar lymph node and 2 bronchi. Tuberculous bronchonodal fistula is formed by erosion of lymph nodes into adjacent airway through inflammation and necrosis.[14] Tuberculous bronchonodal fistula in adults is extremely rare, contrary to that in children. Park et al[14] have reported CT and clinical characteristics of tuberculous bronchonodal fistula in 7 adult patients. In their study, all patients were over 70 years old without major immunosuppressive diseases. All patients had extensive pulmonary TB and TB lymphadenitis. Fistula was formed between hilar lymph node and lobar bronchus on the right side or between subcarinal lymph node and the main bronchus on the left side. Similar to their study, our patient was also over 70 years old. In addition, the fistula was formed between the right hilar lymph node and lobar bronchus. However, the present case showed a more aggressive form. A lymph node was connected with 2 different bronchi, showing a feature of interbronchial fistula mediated by intervening TB lymph node. In addition, our patient did not show any parenchymal TB lesions on initial CT or follow-up CT. Mediastinal/hilar TB lymphadenitis is rare in the absence of simultaneous parenchymal lesions, particularly in immunocompetent patients.[15] Since our patient cumulated multiple immunosuppressive factors, including the underlying condition (SLE) and treatment with corticosteroids, latent TB infection involving lymph node might have been reactivated and rapidly progressed, ultimately forming fistula with adjacent bronchi.

Diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB and related complications can be delayed in immunocompromised patients due to nonspecific clinical presentation and frequent concomitant medical problems. In this study, initial and follow-up CT provided useful information regarding the origin and progress of the disease. Especially, 3-dimensionally reconstructed CT image of tracheobronchial trees helped the physician understand the disease status and guided bronchoscopic examination. On initial bronchoscopy, the physician missed the lesion in the bronchus intermedius without understanding imaging findings. Therefore, the physician had to repeat bronchoscopic examination after reviewing and discussing CT findings. According to Park et al,[14] bronchoscopist can overlook the presence of fistula because the fistulous tract is often concealed and covered by exudate or necrotic tissue. They might consider the disease as a mere endobronchial TB. Thus, the presence and precise location of fistula should be documented through CT scan before bronchoscopy.

Tuberculous bronchonodal fistula can be treated with anti-TB medication.[14] According to microbiological examination of sputum and bronchial aspirates, anti-TB medication was started with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and moxifloxacin. Follow-up bronchoscopy showed decreased size of fistula.

In summary, a rare case of isolated bronchonodal fistula in an elderly male patient with SLE which occurred as the first presentation of TB is reported here. In immunocompromised patients, imaging studies may play crucial role in patient care. Serial chest CT scans with multiplanar reformation and 3-dimensional reconstruction can help physicians understand disease progression and current status, thus aiding a definite diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Keunyoung Bae for the English language review.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CT = computed tomography, SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus, TB = tuberculosis.

Authors’ contributions: Concept and design: KB and KNJ. Acquisition of data: HCK and YSS. Analysis and interpretation of data: GDL, J-YK, and DHS. Drafting the manuscript: KB and KNJ. Final approval: All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Yun JE, Lee SW, Kim TH, et al. The incidence and clinical characteristics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection among systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis patients in Korea. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2002;20:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Woodring JH, Vandiviere HM, Lee C. Intrathoracic lymphadenopathy in postprimary tuberculosis. South Med J 1988;81:992–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Krishnan B, Shaukat A, Chakravorty I. Fatal haemoptysis in a young man with tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenitis. A case report and review of the literature. Respiration 2009;77:333–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kasilingam SK, Sinha N, Kambar V, et al. Mediastinal tubercular lymph node eroding into pericardium causing acute pyopericardium and cardiac tamponade. Trop Doct 2014;44:114–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Erlank A, Goussard P, Andronikou S, et al. Oesophageal perforation as a complication of primary pulmonary tuberculous lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Radiol 2007;37:636–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lado Lado FL, Golpe Gómez A, Cabarcos Ortiz de Barron A, et al. Bronchoesophageal fistulae secondary to tuberculosis. Respiration 2002;69:362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lucas S, Andronikou S, Goussard P, et al. CT features of lymphobronchial tuberculosis in children, including complications and associated abnormalities. Pediatr Radiol 2012;42:923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marchiori E, Francisco FA, Zanetti G, et al. Lymphobronchial fistula: another complication associated with lymphobronchial tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Radiol 2013;43:252–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chiu YM, Lai CH. Nationwide population-based epidemiologic study of systemic lupus erythematosus in Taiwan. Lupus 2010;19:1250–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Danza A, Ruiz-Irastorza G. Infection risk in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: susceptibility factors and preventive strategies. Lupus 2013;22:1286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hou CL, Tsai YC, Chen LC, et al. Tuberculosis infection in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: pulmonary and extra-pulmonary infection compared. Clin Rheumatol 2008;27:557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tam LS, Li EK, Wong SM, et al. Risk factors and clinical features for tuberculosis among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in Hong Kong. Scand J Rheumatol 2002;31:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yang Y, Thumboo J, Tan BH, et al. The risk of tuberculosis in SLE patients from an Asian tertiary hospital. Rheumatol Int 2017;37:1027–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Park SH, Jeon KN, Park MJ, et al. Tuberculous bronchonodal fistula in adult patients: CT findings. Jpn J Radiol 2015;33:360–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lee KS, Song KS, Lim TH, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary tuberculosis: findings on chest radiographs and CT scans. Am J Roentgenol 1993;160:753–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]