Abstract

Objectives:

Vaccination against tuberculosis with live-attenuated Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is widely used even though its effectiveness is controversial. BCG-lymphadenitis (BCG-LA) is its most common complication. Some studies have proposed that BCG-LA can be associated with primary immunodeficiencies (PIs). This study’s aim is to see whether patients who developed BCG-LA (named as ‘LA’) developed more infections than BCG-vaccinated children without BCG-LA (named as ‘NON-LA’).

Methods:

From January 2009 to April 2014, 31 LA children were seen at the outpatient clinic of the General Hospital of Tijuana, Mexico. Among them, 22 (70.97%), 5 (16.13%) and 4 (12.9%) had axillary, supraclavicular, or both BCG-LA, respectively. No treatment was given and complications were not seen. Per LA subject, a NON-LA not >1 month of age difference and same gender was paired and followed for 3 years to look for ambulatory infections (AINFs), acute otitis media (AOM) and hospitalizations. Surveillance per patient was performed by phone monthly, and they were seen at the clinic every 4 months. All patients were HIV-negative and had no family history of PI. Statistical analyses used were relative risk (RR) with confidence intervals (CI), t test for independent variables and z test.

Results:

In total 62 subjects were enrolled: 31 LA paired with 31 NON-LA. Between them, there were no differences in age, day care attendance and breastfeeding. There were no differences in the total number of AINF per patient (LA: 18.61 avg. ± 5.03 SD versus NON-LA: 18.19 avg. ± 4.17 SD, RR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.33–0.66), AOM total episodes (LA: 30 versus NON-LA: 26, RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.31–0.68) and hospitalizations (LA: 5 versus NON-LA: 4, RR = 1, 95% CI = 0.25–0.74).

Conclusions:

This cohort strongly suggests that BCG-LA in healthy children is not associated with more episodes of AINF and hospitalizations, when paired and compared with children BCG-vaccinated without BCG-LA.

Keywords: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, BCG; Lymphadenitis; Primary Immunodficiencies; Children

Background

The use of live-attenuated Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) as a vaccine against some forms of tuberculosis is widely used, despite controversial effectiveness.1,2 The United States and some other developed countries do not use the BCG vaccine.3

The most common complication after BCG vaccination is BCG-lymphadenitis (BCG-LA), with a presentation rate of <1 per 1000 vaccinated children.4 Other, more severe complications include disseminated BCG infections, which are mostly associated with severe immunodeficiencies.4,5

Treatment of BCG-LA is controversial; however, a recent meta-analysis recommends conservative management, with no need for anti-tuberculous drugs or needle aspiration.6

Interestingly, some studies have proposed that BCG-LA can be associated with primary immunodeficiencies (PIs). However, these publications are mostly based on case reports and retrospective studies.7–9

There are several studies documenting PI with BCG-LA, including a case report of a patient who developed disseminated BCG with a partial recessive interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency and two relatives with ZAP70 deficiency, and severe combined immunodeficiency syndrome (SCID).7 Another study reported nine children with PI syndromes who developed persistent BCG-LA.9 A 2-year prospective cohort study found that multiple and recurrent BCG-LAs are associated with some immunological deficiency markers, such as low counts of CD3, CD8, CD19, CD16/CD56 and NK cells.10

In Mexico, routine BCG vaccination is mandatory for all newborns (all should be vaccinated before being discharged from the hospital following delivery).

The purpose of this study is to prospectively identify (based on a 3-year cohort) whether children with BCG-LA present higher numbers of ambulatory infections (AINFs) [with emphasis on upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) and acute diarrheas (ADs)], acute otitis media (AOM) and hospitalizations, when compared with pair-matched children (same age and gender) who are BCG-vaccinated but without BCG-LA.

Methods

Thirty-one children with BCG-LA were seen at the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Outpatient Clinic, General Hospital of Tijuana, Mexico, from January 2009 to April 2014. All children were consistently vaccinated in our hospital at birth, according to the Mexican immunization calendar.

Among the 31 subjects with BCG-LA, 22 (70.97%) had axillary, five (16.13%) had supraclavicular and four (12.9%) presented with both. No treatment was given (neither medication nor needle aspiration), and eight (25.8%) developed spontaneous drainage. None of these patients developed any kind of complication, and BCG-LA completely resolved between 2–4 months for all patients.

Each patient with BCG-LA enrolled in our study was ‘matched’ with an infant ‘control’ who had received the BCG vaccine but without LA. Both patient (named as LA) and control (named as NON-LA) subjects were enrolled at similar ages (no more than a 1-month difference) and same gender, and followed for 3 years for AINF, AOM and hospitalizations. The same methodology was used for all subjects.

Surveillance was made by phone (a questionnaire asking for confirmed AINF and AOM) and in the clinic every 4 months. Questionnaires done by phone collected breastfeeding information for the first 6 months of age and day care attendance information. In addition, vaccination charts were monitored and a complete physical examination, including height and weight, was conducted at each follow-up visit.

For AINF, a URTI was defined as common cold, pharyngitis and/or croup (ambulatory), but without AOM. An AD was defined as an ambulatory diarrhea of <7 days. All AINF (both URTI and AD) were certified by a physician (by phone), or in person at our clinic.

If any immunizations (according to the Mexican calendar) were lacking, they were administered to all subjects during their visits to the clinic. Data from any hospitalization records were gathered prospectively from our hospital.

Before the study’s initiation, all patients (LA and NON-LA) were tested and confirmed to be HIV-negative (by ELISA), had no reported family history of PI and had an initial normal chest X-ray.

Statistical analysis used was calculation of relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), t test for independent variables and z test (the statistical program used was Epi-Info® version 7). Sample estimation was performed for convenience.

The study was accepted by the hospital’s IRB, and a consent form was signed by at least one parent/legal guardian of each patient included in the study.

The study was completely observational, no interventions were performed.

Results

Sixty-two subjects were enrolled, of which 31 LA patients were paired with 31 NON-LA patients. Adherence to this cohort following 3 years of surveillance was 100% for both groups. As seen in detail in Table 1, there were no statistical differences in age at admission (LA: 119 Avg. ± 30 SD versus NON-LA: 121 Avg. ± 31 SD, days, p = 0.75, CI ± 11), gender (17 females and 14 males per pair-matched group), day care attendance (LA: 9 (29%) versus NON-LA: 13 (42%), p = 0.28) and 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding (LA: 21 (67%) versus NON-LA 18 (58%), p = 0.43).

Table 1.

Comparison in age, gender, day care attendance and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months, between cases and control.

| Groups | Age (days) | Gender | Day care attendance | Breastfeeding for 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA | 119 Avg. ± 30 SD | 14 (45%) M, 17 (55%) F | 9 (29%) | 21 (67%) |

| NON-LA | 121 Avg. ± 31 SD | 14 (45%) M, 17 (55%) F | 13 (42%) | 18 (58%) |

| p-value | 0.75 (± 11 CI) | Not applicable. Pairing was also by gender. | 0.28 | 0.43 |

All patients were fully vaccinated based on the Mexican immunization calendar, and malnutrition was not seen in any subject.

Among all 1141 AINF episodes (LA: 577, NON-LA: 564), most were URTIs (LA: 560, NON-LA: 544), with 37 AD total episodes (LA: 17, NON-LA: 20).

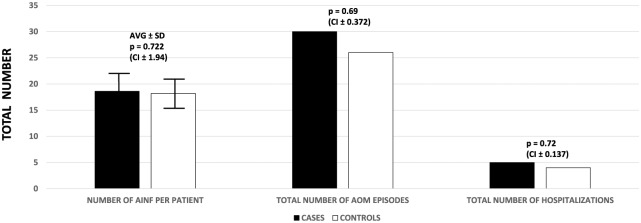

As seen in Figure 1, following 3 years of closed surveillance, there were no differences in the total number of AINFs per patient (LA: 18.61 Avg. ± 5.03 SD versus NON-LA: 18.19 Avg. ± 4.17 SD, RR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.33–0.66), AOM total episodes (LA: 30 versus NON-LA: 26, RR = 0.87, 95% CI = 0.31–0.68) and hospitalizations (LA: 5 versus NON-LA: 4, RR = 1, 95% CI = 0.25–0.74).

Figure 1.

Number of AINF per patient (including URTI and AD), total episodes of AOM and total number of hospitalizations, per group.

Of the hospitalized patients, all were diagnosed with an acute respiratory infection. In the LA group, four had bronchiolitis and one pneumonia; in the NON-LA group three cases of bronchiolitis and one pneumonia were reported.

Discussion

Despite the limitations and controversy regarding efficacy of the BCG vaccine against extrapulmonary tuberculosis infections, and duration of immunity, the BCG vaccine remains the only vaccine globally administered against this disease.1,2 Several complications following its administration have been well documented. The most frequent is BCG-LA, with a proportion varying from 0.1 to 1%.4 In addition, some publications have reported that BCG-LA could be associated with PI in HIV-negative patients.7–10

A study done by Santos and colleagues reported three cases of BCG disease in children with PI: one with a patient with a partial recessive interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency who developed BCG dissemination, and two relatives with ZAP70 deficiency and an SCID, both of whom presented with regional BCG-LA. The authors recommended in this study that BCG vaccination should be delayed in all newborns with a family history of PI, until these conditions have been ruled out.7

In the review by Guerin and Bregere, the authors found that any immunodeficiency could be a contraindication for BCG vaccination, especially HIV-infected children.8 Furthermore, recent data from South Africa make clear that BCG vaccination in HIV-infected children is associated with significant safety concerns in untreated infants, including those treated with antiretroviral therapy.11

There has been publication of nine children with PI syndromes who developed persistent BCG-LA or disseminated BCG infections following BCG vaccination. This study, performed in Chile over a period of 10 years, reported an incidence of severe BCG infections (3.4/1,000,000 vaccinated newborns) mainly in children with severe PI syndromes. The clinical presentation and course of infection varied considerably, depending on the underlying immunodeficiency. In this study, only seven patients presented with ‘only’ BCG-LA, and none died as a result. The two patients who developed BCG-disseminated disease (not only BCG-LA) and did die in the study had SCID.9

The only longitudinal study prospectively looking for PI during BCG adverse events was conducted by Samileh and colleagues in Iran. Seventy-five children between 2 months and 14 years of age were followed for 2 years. Their results found that patients who developed BCG-LA had a significantly lower total count of CD3, CD8, CD19, CD16/CD56 and NK cells, but no differences in the CD4/CD8 ratio. In this study, no patient with BCG-LA (either with laboratory confirmed immunodeficiency or not) developed clinically evident complications.10

BCG adverse events have also been associated with the strain used, age at application and number of doses.4,11–13

In Mexico, the BCG strain uniformally used for vaccination is a culture obtained from BCG-1-361, derived from the Moscow strain (Serum Institute of India®).14

Another study, in which mice were inoculated with 13 different BCG strains to assess virulence, showed the highest virulence among the DU2 group VI (BCG-Phipps, BCG-Frappier, BCG-Pasteur, and BCG-Ticet). Strains of BCG belonging to the DU2 group II (BCG-Sweden, BCG-Mirkhaug) were the least virulent. Furthermore, the ‘Russian’ strain was reported as ‘the ninth least virulent’ in this animal model.13

Our study did not focus on treatment of BCG-LA, as mentioned. Nevertheless, all children had a good outcome without any kind of medical or surgical intervention.

To our knowledge, this study is the first cohort that specifically looks at the number of confirmed ambulatory and hospitalized cases of infections in children (without HIV or a family history of PI) who developed a single episode of BCG-LA, versus BCG-vaccinated without BCG-LA. The study was a strictly paired control, matched for gender and age, with no differences in day care attendance and exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months. In addition, all children had a normal chest X-ray at admission, were fully vaccinated based on the Mexican immunization calendar, and none developed malnutrition during the 3 years of surveillance.

Our results reveal that healthy children who have a single episode of BCG-LA are not at risk of developing a higher number of episodes of any AINFs (including AOM) and hospitalizations of any kind, for at least the first 3 years of age. The highest risk during childhood for AINF (including AOM) are within the first 5 years of life.15 In our cohort, even though we did not look at specific immunological markers, patients who had BCG-LA clinically behaved very similarly to children who never developed BCG-LA but were BCG-vaccinated. This strongly suggests that the presence of a unique episode of BCG-LA may not be a marker of immunodeficiency in the HIV-negative population, or those without a family history of PI.

Potential limitations of our study are that our patients were enrolled only from one hospital setting, and the sample size is not representative of BCG-LA consequences from a national Mexican perspective. Other limitations include: surveillance was done monthly by phone and may not detect all AINFs; follow up for 3 years may not be sufficient time. However, the ‘paired-matches’ of our subjects, with great similarity between the two groups and physical monitoring of each infant every 4 months to obtain a new clinical history, complete physical examination and ensuring that vaccination was complete, makes this study significantly more reliable.

It is possible that in the near future a new vaccine against tuberculosis may be developed.16 Nevertheless, BCG should be remembered as a safe vaccine in healthy children, albeit less effective.

Conclusions

This 3-year cohort strongly suggests that one episode of BCG-LA in otherwise healthy children is not associated with more episodes of AINFs and hospitalizations, when paired and compared to BCG-vaccinated healthy children who never developed BCG-LA.

Larger cohorts, along with specific immunological markers, could be useful to fully determine whether a single episode of BCG-LA in HIV-negative children is associated or not with PI.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Enrique Chacon-Cruz, Hospital General de Tijuana – Pediatrics, Paseo Centario S/N Zona del Rio, Tijuana, Baja-California 22010, Mexico.

Jorge Luis Arellano-Estrada, Health Jurisdiction of Tijuana – Epidemiology, Tijuana Baja-California, Mexico.

Erika Lopatynsky-Reyes, Universidad Autonoma de Baja-California Campus ECISALUD – School of Medicine, Tijuana, Baja-California, Mexico.

Jorge Alvelais-Palacios, Universidad Autonoma de Baja-California Campus ECISALUD – School of Medicine, Tijuana, Baja-California, Mexico.

Chandra Becka, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Ringgold Standard Institution – Internal Medicine, Brownsville, Texas, USA.

References

- 1. Roy A, Eisenhut M, Harris RJ, et al. Effect of BCG vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014; 349: g4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abubakar I, Pimpin L, Ariti C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the duration of protection by Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination against tuberculosis. Health Technol Assess 2013; 17: 1–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. The role of BCG vaccine in the prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United States. MMWR 1996; 45: RR4. [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. BCG Vaccine WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2004; 79: 27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elsidig N, Alsharani D, Alsherhi M, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine related lymphadenitis in children: management guidelines endorsed by the Saudi Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (SPIDS). Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med 2015; 2: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cuello-Garcia CA, Perez-Gaxiola G, Jimenez-Gutierrez C. Treating BCG-induced disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013: CD008300. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008300.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santos A, Dias A, Cordeiro A, et al. Severe axillary lymphadenitis after BCG vaccination: alert for primary immunodeficiencies. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2010; 43: 530–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guerin N, Bregere P. BCG vaccination. Child Trop 1992: 72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gonzalez B, Moreno S, Burdach R, et al. Clinical presentation of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin infections in patients with immunodeficiency syndromes. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1989; 8: 201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Samileh N, Ahmad S, Farzaneh A, et al. Immunity status in children with Bacille Calmette-Guerin adenitis: a prospective study in Tehran, Iran. Saudi Med J 2006; 27: 1719–1724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nutall JJC, Eley BS. BCG vaccination in HIV-infected children. Tuberc Res Treat 2011: Article ID 712736. DOI: 10.1155/2011/712736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dommergues MA, de La Rocque F, Guy C, et al. Local and regional adverse reactions to BCG-SSI vaccination: a 12 month cohort follow-up study. Vaccine 2009; 27: 6967–6973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang L, Huan-wei R, Fu-zeng C, et al. Variable virulence and efficacy of BCG vaccine strains in mice and correlation with genome polymorphisms. Mol Ther 2016; 24: 398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. COFEPRIS. FICHA TÉCNICA VACUNA BCG (LIOFILIZADA), www.cofepris.gob.mx/AS/Documents/RegistroSanitarioMedicamentos/Vacunas/302M2004.PDF (2014, accessed 20 June 2017).

- 15. Monto AS, Ullman BM. Acute respiratory illness in an American community: the Tecumseh Study. JAMA 1974; 227: 164–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahsan MJ. Recent advances in the development of vaccines for tuberculosis. Ther Adv Vaccines 2015; 3: 66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]